Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

434

CHAPTER 18

THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

Toward a New Heaven and a New Earth:

An Intellectual Revolution in the West

Q

Who were the leading figures of the Scientific

Revolution and the Enlightenment, and what were

their main contributions?

Economic Changes and the Social Order

Q

What changes occurred in the European economy in

the eighteenth century, and to what degree were these

changes reflected in social patterns?

Colonial Empires and Revolution in the Western

Hemisphere

Q

How did Spain and Portugal administer their American

colonies, and what were the main characteristics of

Latin American society in the eighteenth century?

Toward a New Political Order and Global Conflict

Q

What do historians mean by the term enlightened

absolutism, and to what degree did eighteenth-century

Prussia, Austria, and Russia exhibit its characteristics?

The French Revolution

Q

What were the causes, the main events, and the results

of the French Revolution?

The Age of Napoleon

Q

Which aspects of the French Revolution did Napoleon

preserve, and which did he destroy?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

In what ways were the American Revolution, the French

Revolution, and the seventeenth-century English

revolutions alike? In what ways were they different?

The storming of the Bastille

ON THE MORNING OF JULY 14, 1789, a Parisian mob

of some eight thousand men and women in search of weapons

streamed toward the Bastille, a royal armory filled with arms and

ammunition. The Bastille was also a state prison, and although it

held only seven prisoners at the time, in the eyes of these angry

Parisians, it was a glaring symbol of the government’s despotic poli-

cies. It was defended by the marquis de Launay and a small garrison

of 114 men. The attack on the Bastille began in earnest in the early

afternoon, and after three hours of fighting, de Launay and the gar-

rison surrendered. Angered by the loss of ninety-eight protesters, the

victors beat de Launay to death, cut off his head, and carried it

aloft in triumph through the streets of Paris. When King Louis XVI

was told the news of the fall of the Bastille by the duc de La

Rochefoucauld-Liancourt, he exclaimed, ‘‘Why, this is a revolt.’’

‘‘No, Sire,’’ replied the duke. ‘‘It is a revolution.’’

The French Revolution was a key factor in the emergence of a

new world order. Historians have often portrayed the eighteenth

century as the final phase of Europe’s old order, before the violent

upheaval and reordering of society associated with the French Revo-

lution. The old order---still largely agrarian, dominated by kings and

landed aristocrats, and grounded in privileges for nobles, clergy,

435

c

R

eunion des Mus

ees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

Toward a New Heaven and a New

Earth: An Intellectual Revolution

in the West

Q

Focus Question: Who were the leading figures of the

Scientific Revolution and the Enlightenment, and what

were their main contributions?

In the seventeenth century, a group of scientists set the

Western world on a new path known as the Scientific

Revolution, which gave Europeans a new way of viewing

the universe and their place in it. The Scientific Revolu-

tion affected only a small number of Europe’s educated

elite. But in the eighteenth century, this changed dra-

matically as a group of intellectuals popularized the ideas

of the Scientific Revolution and used them to undertake a

dramatic reexamination of all aspects of life. The wide-

spread impact of these ideas on their society has caused

historians ever since to call the eighteenth century in

Europe the Age of Enlightenment.

The Scientific Revolution

The Scientific Revolution ultimately challenged con-

ceptions and beliefs about the nature of the external world

that had become dominant b y the Late Middle Ages.

Toward a New Heaven: A Revolution in Astr onomy The

philosophers of the Middle Ages had used the ideas of

Aristotle, Ptolemy (the greatest astronomer of antiquity,

who lived in the second century

C.E.), and Christianity to

form the Ptolemaic or geocentric theory of the universe.

In this conception, the universe was seen as a series of

concentric spheres with a fixed or motionless earth at its

center. Composed of material substance, the earth was

imperfect and constantly changing. The spheres that

surrounded the ear th were made of a crystalline, trans-

parent substance and moved in circular orbits around the

earth. The heavenly bodies, believed to number ten in

1500, were pure orbs of light, embedded in the moving,

concentric spheres. Working outward from the earth, the

first eight spheres contained the moon, Mercury, Venus,

the sun, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, and the fixed stars. The

ninth sphere imparted to the eighth sphere of the fixed

stars its daily motion, while the tenth sphere was fre-

quently described as the prime mover that moved itself

and imparted motion to the other spheres. Beyond the

tenth sphere was the Empyrean Heaven---the location of

God and all the saved souls. God and the saved souls

were at one end of the universe, then, and humans were

at the center. They had power over the earth, but their

real purpose was to achieve salvation.

Nicolaus Copernicus (1473--1543), a native of Po-

land, was a mathematician who felt that Ptolemy’s geo-

centric system failed to accord with the observed motions

of the heavenly bodies and hoped that his heliocentric

(sun-centered) theory would offer a more accurate ex-

planation. Copernicus argued that the sun was motionless

at the center of the universe. The planets revolved around

the sun in the order of Mercury, Venus, the earth, Mars,

Jupiter, and Saturn. The moon, however, revolved around

the earth. Moreover, what appeared to be the movement

of the sun around the earth was really explained by the

daily rotation of the earth on its axis and the journey of

the earth around the sun each year. But Copernicus did

not reject the idea that the heavenly spheres moved in

circular orbits.

The next step in destroying the geocentric conception

and supporting the Copernican system was taken by

Johannes Kepler (1571--1630). A brilliant German math-

ematician and astronomer, Kepler arrived at laws of

planetary motion that confirmed Copernicus’s heliocen-

tric theory. In his firs t law, however, he revised Copernicus

by showing that the orbits of the planets around the sun

were not circular but elliptical, with the sun at one focus

of the ellipse rather than at the center.

Kepler’s work destroyed the basic structure of the

Ptolemaic system. People could now think in new terms

of the actual paths of planets revolving around the sun in

elliptical orbits. But important questions remained un-

answered. For example, what were the planets made of ?

An Italian scientist achieved the next important break-

through to a new cosmology by answering that question.

Galileo Galilei (1564--1642) taught mathematics and

was the first European to make systematic observations of

the heavens by means of a telescope, inaugurating a new

age in astronomy. Galileo turned his telescope to the skies

and made a remarkable series of discoveries: mountains

436 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

towns, and provinces---seemed to continue a basic pattern that had

prevailed in Europe since medieval times. But, just as a new intellec-

tual order based on rationalism and secularism was emerging in

Europe, demographic, economic, social, and political patterns were

beginning to change in ways that proclaimed the emergence of a

modern new order.

The French Revolution demolished the institutions of the old

regime and established a new order based on individual rights, rep-

resentative institutions, and a concept of loyalty to the nation rather

than to the monarch. The revolutionar y upheavals of the era, espe-

cially in France, created new liberal and national political ideals,

summarized in the French revolutionary slogan, ‘‘Liberty, Equality,

Fraternity,’’ that transformed France and then spread to other

European countries and the rest of the world.

on the moon, four moons revolving around Jupiter, and

sunspots. Galileo’s observations seemed to destroy yet

another aspect of the traditional cosmology in that the

universe seemed to be composed of material similar to

that of earth rather than a perfect and unchanging

substance.

Galileo’s revelations, published in The Starry Mes-

senger in 1610, made Europeans aware of a new picture of

the universe. But the Catholic church condemned Co-

pernicanism and ordered Galileo to abandon the Co-

pernican thesis. The church attacked the Copernican

system because it threatened not only Scripture but also

an entire conception of the universe. The heavens were no

longer a spiritual world but a world of matter.

By the 1630s and 1640s, most astronomers had come

to accept the new heliocentric conception of the universe.

Nevertheless, the problem of explaining motion in the

universe and tying together the ideas of Copernicus,

Galileo, and Kepler had not yet been done. This would be

the work of an Englishman who has long been considered

the greatest genius of the Scientific Revolution.

Isaac Newton (1642--1727) taught at Cambridge

University, where he wrote his major work, Mathematical

Principles of Natural Philosophy, known simply as the

Principia by the first word of its Latin title. In the first

book of the Principia, Newton defined the three laws of

motion that govern the planetary bodies, as well as ob-

jects on earth. Crucial to his whole argument was the

universal law of gravitation, which explained why the

planetary bodies did not go off in straight lines but

continued in elliptical orbits about the sun. In mathe-

matical terms, Newton explained that every object in the

universe is attracted to every other object by a force called

gravity.

Newton had demonstrated that one mathematically

proven universal law could explain all motion in the

universe. At the same time, the Newtonian synthesis

created a new cosmology in which the universe was seen

as one huge, regulated machine that operated according

to natural laws in absolute time, space, and motion.

Newton’s world-machine concept dominated the modern

worldview until the twentieth century, when Albert

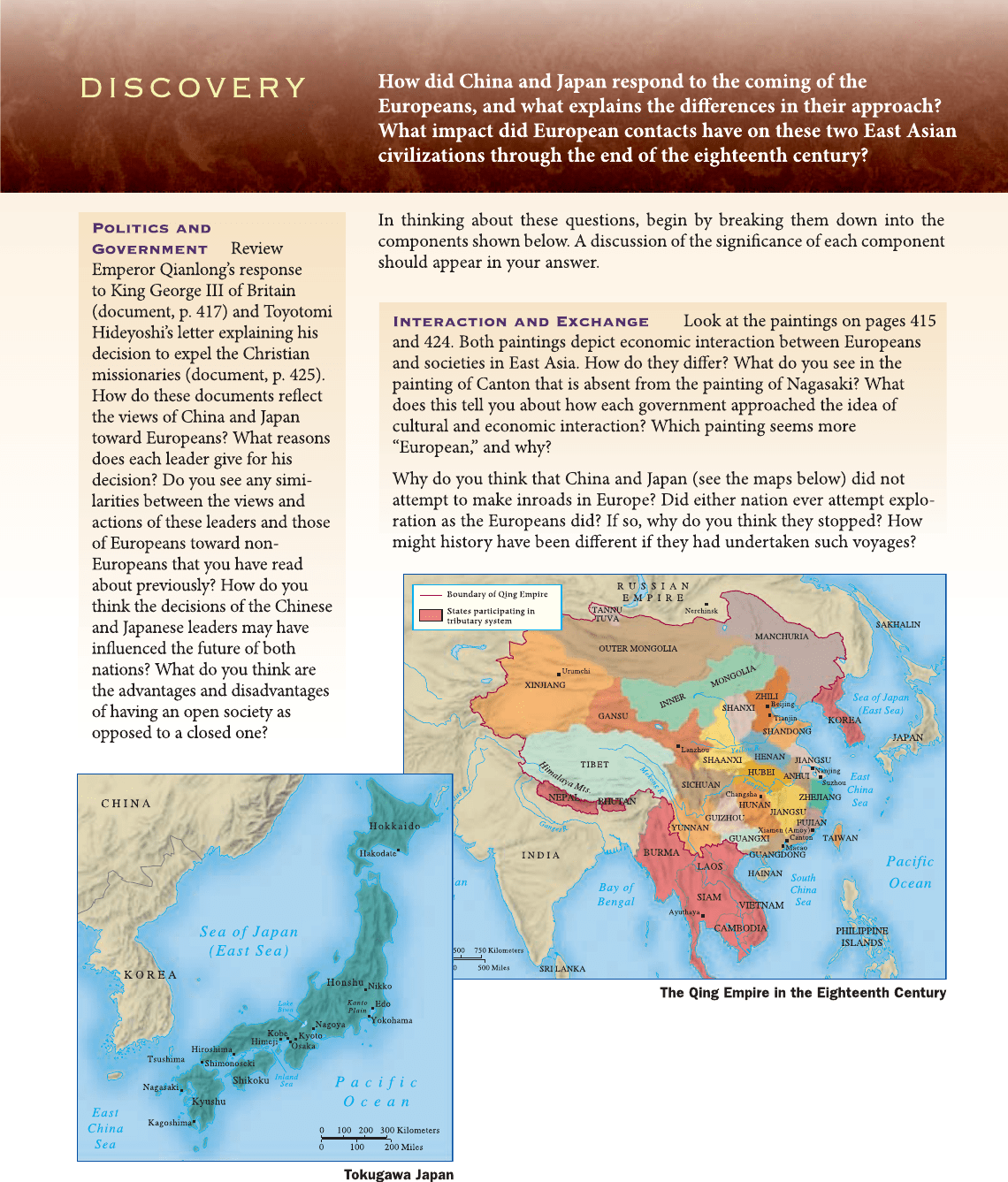

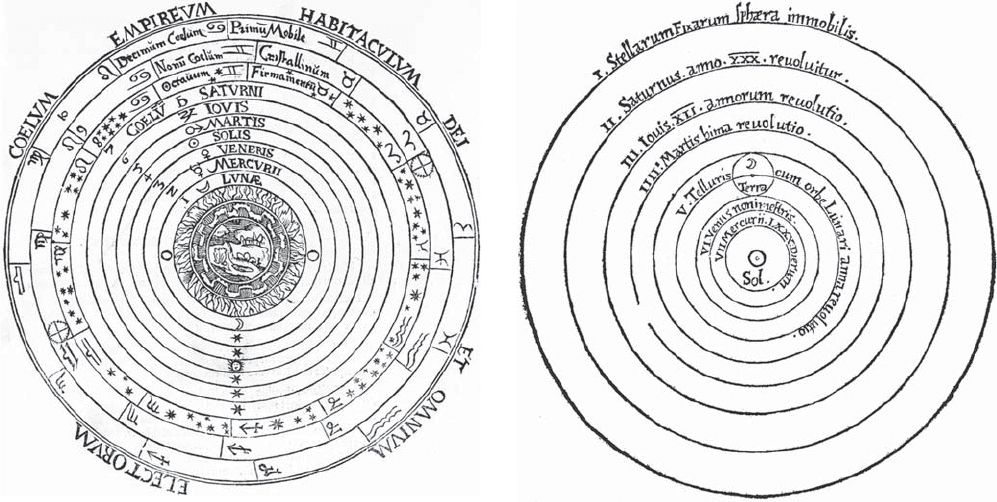

The Copernican System. The Copernican system was presented in

On the Revolutions of the Heavenly Spheres, published shortly before

Copernicus’s death. As shown in this illustration from the first edition of

the book, Copernicus maintained that the sun was the center of the

universe while the planets, including the earth, revolved around it.

Moreover, the earth rotated daily on its axis. (The circles read, from the

outside in: 1. Immobile Sphere of the Fixed Stars, 2. Saturn, orbit of

30 years, 3. Jupiter, orbit of 12 years, 4. Mars, orbit of 2 years, 5. Earth,

with the moon, orbit of one year, 6. Venus, 7. Mercury, orbit of 80 days,

8. Sun.)

Medieval Conception of the Universe. As this sixteenth-century

illustration shows, the medieval cosmological view placed the earth at the

center of the universe, surrounded by a series of concentric spheres. The

earth was imperfect and constantly changing, while the heavenly bodies

that surrounded it were perfect and incorruptible. Beyond the tenth and

final sphere was heaven, where God and all the saved souls were located.

(The circles read, from the center outward: 1. Moon, 2. Mercury, 3. Venus,

4. Sun, 5. Mars, 6. Jupiter, 7. Saturn, 8. Firmament of the Stars, 9. Crystalline

Sphere, 10. Prime Mover, and at the end, Empyrean Heaven—Home of God

and all the Elect, that is, saved souls.)

c

Image Select/Art Resource, NY

c

Image Select/Art Resource, NY

TOWARD A NEW HEAVEN AND A NEW EARTH:AN INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTIONINTHEWEST 437

Einstein’s concept of relativity created a new picture of

the universe.

Europe, China, and Scientific Revolutions An inter-

esting question that arises is why the Scientific Revolution

occurred in Europe and not in China. In the Middle Ages,

China had been the most technologically advanced civi-

lization in the world. After 1500, that distinction passed

to the West (see the comparative essay ‘‘The Scientific

Revolution’’ above). Historians are not sure why. Some

have compared the sense of order in Chinese society to

the competitive spirit existing in Europe. Others have

emphasized China’s ideological viewpoint that favored

living in harmony with nature rather than trying to

dominate it. One historian has even suggested that

China’s civil service system drew the ‘‘best and the

brightest’’ into government service, to the detriment of

other occupations.

Background to the Enlightenment

The impetus for political and social change in the eigh-

teenth century stemmed in part from the Enlightenment.

The Enlightenment was a movement of intellectuals who

were greatly impressed with the accomplishments of the

Scientific Revolution. When they used the word reason---

one of their favorite words---they were advocating the

application of the scientific method to the understanding

COMPARATIVE ESSAY

T

HE SCIENTIFIC REVOLUTION

When Catholic missionaries began to arrive in

China during the sixteenth century, they marveled

at the sophistication of Chinese civilization and its

many accomplishments, including woodblock print-

ing and the civil service examination system. In turn, their

hosts were impressed with European inventions such as the

spring-driven clock and eyeglasses.

It is no surprise that the visitors fr om

theWestwereimpressedwithwhatthey

saw in China, for that country had long

been at the foref ront of human achieve-

ment. From now on, howev er, Europe

would take the lead in the advance of

science and technology, a phenomenon

that would ultimately result in bringing

about the Industrial Revolution and be-

ginning a transformation of human so-

ciety that would lay the foundations of

the modern world.

Why did Europe suddenly become

the engine for rapid global change in

the seventeenth and eighteenth centu-

ries? One factor was the change in the

European worldview, the shift from a

metaphysical to a materialist perspec-

tive and the growing inclination among

European intellectuals to question first principles. Whereas in China,

for example, the ‘‘investigation of things’’ proposed by Song dynasty

thinkers had been put to use analyzing and confirming principles

first established by Confucius and his contemporaries, empirical

scientists in early modern Europe rejected received religious ideas,

developed a new conception of the universe, and sought ways to im-

prove material conditions around them.

Why were European thinkers more interested in practical appli-

cations of their discoveries than their counterparts elsewhere? No

doubt the literate mercantile and propertied elites of Europe were

attracted to the new science because it offered new ways to exploit

resources for profit. Some of the early scientists made it easier for

these groups to accept the new ideas by

showing how they could be applied

directly to specific industrial and techno-

logical needs. Galileo, for example, con-

sciously drew a connection between

science and the material interests of the

educated elite when he assured his listen-

ers that the science of mechanics would be

quite useful ‘‘when it becomes necessary

to build bridges or other structures over

water, something occurring mainly in

affairs of great importance.’’

A final factor was the political changes

that were beginning to take place in Europe

during this period. Many European states

enlarged their bureaucratic machinery and

consolidated their governments in order to

collect the revenues and amass the armies

needed to compete militarily with rivals.

Political leaders desperately sought ways to

enhance their wealth and power and grasped eagerly at whatever tools

were available to guarantee their survival and prosperity.

Q

Why did the Scientific Revolution emerge in Europe and not

in China?

The telescope—a European invention

c

The Print Collector/Alamy

438 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

of all life. All institutions and all systems of thought were

subject to the rational, scientific way of thinking if people

would only free themselves from the shackles of past,

worthless traditions, especially religious ones. If Isaac

Newton could discover the natural laws regulating the

world of nature, they too, by using reason, could find the

laws that governed human society. This belief in turn led

them to hope that they could make progress toward a

better society than the one they had inherited. Reason,

natural law, hope, progress---these were the buzzwords in

the heady atmosphere of eighteenth-century Europe.

Major sources of inspiration for the Enlightenment

were two Englishmen, Isaac Newton and John Locke

(1632--1704). As mentioned earlier, Newton contended

that the world and everything in it worked like a giant

machine. Enchanted by the grand design of this world-

machine, the intellectuals of the Enlightenment were

convinced that by following Newton’s rules of reasoning,

they could discover the natural laws that governed poli-

tics, economics, justice, and religion.

John Locke’s theory of knowledge also made a great

impact. In his Essay Concerning Human Understanding,

written in 1690, Locke denied the existence of innate

ideas and argued instead that every person was born with

a tabula rasa, a blank mind:

Let us then suppose the mind to be, as we say, white paper,

void of all characters, without any ideas. How comes it to be

furnished? Whence comes it by that vast store which the

busy and boundless fancy of man has painted on it with an

almost endless variety? Whence has it all the materials of rea-

son and knowledge? To this I answer, in one word, from

experience. ... Our observation, employed either about ex-

ternal sensible objects or about the internal operations of

our minds perceived and reflected on by ourselves, is that

which supplies our understanding with all the materials

of thinking.

1

By denying innate ideas, Locke’s philosophy implied that

people were molded by their environment, by whatever

they perceived through their senses from their sur-

rounding world. By changing the environment and sub-

jecting people to proper influences, they could be

changed and a new society created. And how should the

environment be changed? Newton had paved the way:

reason enabled enlightened people to discover the natural

laws to which all institutions should conform.

The Philosophes and Their Ideas

The intellectuals of the Enlightenment were known by the

French term philosophes, although they were not all

French and few were philosophers in the strict sense of

the term. The philosophes were literary people, pro-

fessors, journalists, economists, political scientists, and,

above all, social reformers. Although it was a truly in-

ternational and cosmopolitan movement, the Enlighten-

ment also enhanced the dominant role being played by

French culture; Paris was its recognized capital. Most of

the leaders of the Enlightenment were French. The French

philosophes, in turn, affected intellectuals elsewhere and

created a movement that touched the entire Western

world, including the British and Spanish colonies in the

Americas.

To the philosophes, the role of philosophy was not

just to discuss the world but to change it. A spirit of

rational criticism was to be applied to everything, in-

cluding religion and politics. Spanning almost a century,

the Enlightenment evolved with each succeeding genera-

tion, becoming more radical as new thinkers built on the

contributions of their predecessors. A few individuals,

however, dominated the landscape so completely that we

can gain insight into the core ideas of the philosophes by

focusing on the three French giants---Montesquieu, Vol-

taire, and Diderot.

Montesquieu Charles de Secondat, the baron de

Montesquieu (1689--1755), came from the French no-

bility. His most famous work, The Spirit of the Laws, was

published in 1748. In this comparative study of govern-

ments, Montesquieu attempted to apply the scientific

method to the social and political arena to ascertain the

‘‘natural laws’’ governing the social and political rela-

tionships of human beings. Montesquieu distinguished

three basic kinds of governments: republic, monarchy,

and despotism.

Montesquieu used England as an example of mon-

archy, and it was his analysis of England’s constitution

that led to his most lasting contribution to political

thought---the importance of checks and balances achieved

by means of a separation of powers. He believed that

England’s system, with its separate executive, legislative,

and judicial powers that served to limit and control each

other, provided the greatest freedom and security for a

state. The translation of his work into English two years

after publication ensured that it would be read by

American political leaders, who eventually incorporated

its principles into the U.S. Constitution.

Voltaire The greatest figure of the Enlightenment was

Franc¸ois-Marie Arouet, known simply as Voltaire (1694--

1778). Son of a prosperous middle-class family from

Paris, he studied law, although he achieved his first suc-

cess as a playwright. Voltaire was a prolific author and

wrote an almost endless stream of pamphlets, novels,

plays, letters, philosophical essays, and histories.

Voltaire was especially well known for his criticism of

traditional religion and his strong attachment to the ideal

TOWARD A NEW HEAVEN AND A NEW EARTH:AN INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTIONINTHEWEST 439

of religious toleration. As he grew older, Voltaire became

ever more strident in his denunciations. ‘‘Crush the infa-

mous thing,’’ he thundered repeatedly---the infamous thing

being religious fanaticism, intolerance, and superstition.

Throughout his life, Voltaire championed not only

religious tolerance but also deism, a religious outlook

shared by most other philosophes. Deism was built on the

Newtonian world-machine, which implied the existence

of a mechanic (God) who had created the universe. To

Voltaire and most other philosophes, the universe was like

a clock, and God was the clockmaker who had created it,

set it in motion, and allowed it to run according to its

own natural laws.

Diderot Denis Diderot (1713--1784) was the son of a

skilled craftsman from eastern France who became a

writer so that he could be free to study and read in many

subjects and languages. One of Diderot’s favorite topics

was Christianity, which he condemned as fanatical and

unreasonable. Of all religions, Christianity, he averred,

was the worst, ‘‘the most absurd and the most atrocious

in its dogma.’’

Diderot’s most famous contribution to the Enlight-

enment was the Encyclopedia, or Classified Dictionary of

the Sciences, Arts, and Trades, a twenty-eight-volume

compendium of knowledge that he edited and referred to

as the ‘‘great work of his life.’’ Its purpose, according to

Diderot, was to ‘‘change the general way of thinking.’’ It

did precisely that in becoming a major weapon of the

philosophes’ crusade against the old French society. The

contributors included many philosophes who attacked

religious intolerance and advocated a program for social,

legal, and political improvements that would lead to a

society that was more cosmopolitan, more tolerant, more

humane, and more reasonable. The Encyclopedia was sold

to doctors, clergymen, teachers, lawyers, and even military

officers, thus spreading the ideas of the Enlightenment.

Toward a New ‘‘Science of Man’’ The Enlightenment

belief that Newton’s scientific methods could be used to

discover the natural laws underlying all areas of human

life led to the emergence in the eighteenth century of what

the philosophes called a ‘‘science of man,’’ or what we

would call the social scie nces. In a number of areas, such as

economics, politics, and education, the philosophes arrived

at natural la ws that they believed governed human actions.

Adam Smith (1723--1790) has been v iewed as one of

the founders of the modern discipline of economics.

Smith believed that individuals should be free to pursue

their own economic self-interest. Through the actions of

these individuals, all society would ultimately benefit.

Consequently, the state should in no way interrupt the

free play of natural economic forces by imposing

government regulations on the economy but should leave

it alone, a doctrine that subsequently became known as

laissez-faire (French for ‘‘leave it alone’’).

Smith gave to government only three basic functions:

it should protect society from invasion (army), defend its

citizens from injustice (police), and keep up certain

public works, such as roads and canals, that private in-

dividuals could not afford.

The Later Enlightenment By the late 1760s, a new

generation of philosophes who had grown up with the

worldview of the Enlightenment began to move beyond

their predecessors’ beliefs. Most famous was Jean-Jacques

Rousseau (1712--1778), whose political beliefs were pre-

sented in two major works. In his Discourse on the Origins

of the Inequality of Mankind, Rousseau argued that people

had adopted laws and governors in order to preserve their

private property. In the process, they had become en-

slaved by government. What, then, should people do to

regain their freedom? In his celebrated treatise The Social

Contract, published in 1762, Rousseau found an answer in

the concept of the social contract whereby an entire so-

ciety agreed to be governed by its general will. Each in-

dividual might have a particular will contrary to the

general will, but if the individual put his particular will

(self-interest) above the general will, he should be forced

to abide by the general will. ‘‘This means nothing less than

that he will be forced to be free,’’ said Rousseau, because

the general will was not only political but also ethical; it

represented what the entire community ought to do.

Another influential treatise by Rousseau was his

novel E

´

mile, one of the Enlightenment’s most important

works on education. Rousseau’s fundamental concern was

that education should foster, rather than restrict, chil-

dren’s natural instincts. Rousseau’s own experiences had

shown him the importance of the emotions. What he

sought was a balance between heart and mind, between

emotion and reason.

But Rousseau did not necessarily practice what he

preached. His own children were sen t to orphanages,

where many children died at a young age. Rousseau also

viewed women as ‘‘ naturally’’ different from men. In

Rousseau’ s E

´

mile, Sophie, E

´

mile’s intended wife, was edu-

cated for her role as wife and mother by learning obedience

and the nurturing skills that would enable her to pro vide

loving care for her husband and childr en. Not everyone in

the eighteenth century, ho wev er, agreed with Rousseau.

The ‘‘Woman Question’’ in the Enlightenment For

centuries, many male intellectuals had argued that

the nature of women made them inferior to men and

made male domination of women necessary and right. In

the Scientific Revolution, however, some women had

440 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

made notable contributions. Maria Winkelmann in Ger-

many, for example, was an outstanding practicing as-

tronomer. Nevertheless, when she applied for a position

as assistant astronomer at the Berlin Academy, for which

she was highly qualified, she was denied the post by the

academy’s members, who feared that hiring her would

establish a precedent (‘‘mouths would gape’’).

Female thinkers in the eighteenth century disagreed

with this attitude and provided suggestions for improving

the conditions of women. The strongest statement for the

rights of women was advanced by the English writer Mary

Wollstonecraft (1759--1797), viewed by many as the

founder of modern European feminism.

In her Vindication of the Rights of Woman, written in

1792, Wollstonecraft pointed out two contradictions in

the views of women held by such Enlightenment thinkers

as Rousseau. To argue that women must obey men, she

said, was contrary to the beliefs of the same individuals

that a system based on the arbitrary power of monarchs

over their subjects or slave owners over their slaves was

wrong. The subjection of women to men was equally

wrong. In addition, she argued that the Enlightenment

was based on an ideal of reason innate in all human

beings. If women have reason, then they too are entitled

to the same rights that men have in education and in

economic and political life (see the box above).

Culture in an Enlightened Age

Although the Baroque style that had dominated the sev-

enteenth century continued to be popular, by the 1730s, a

new style of decoration and architecture known as Rococo

had spread throughout Europe. Unlike the Baroque,

which stressed power, grandeur, and movement, Rococo

emphasized grace, charm, and gentle action. Rococo re-

jected strict geometrical patterns and had a fondness for

curves; it liked to follow the wandering lines of natural

objects, such as seashells and flowers. It made much use of

interlaced designs colored in gold with delicate contours

and graceful arcs. Highly secular, its lightness and charm

spoke of the pursuit of pleasure, happiness, and love.

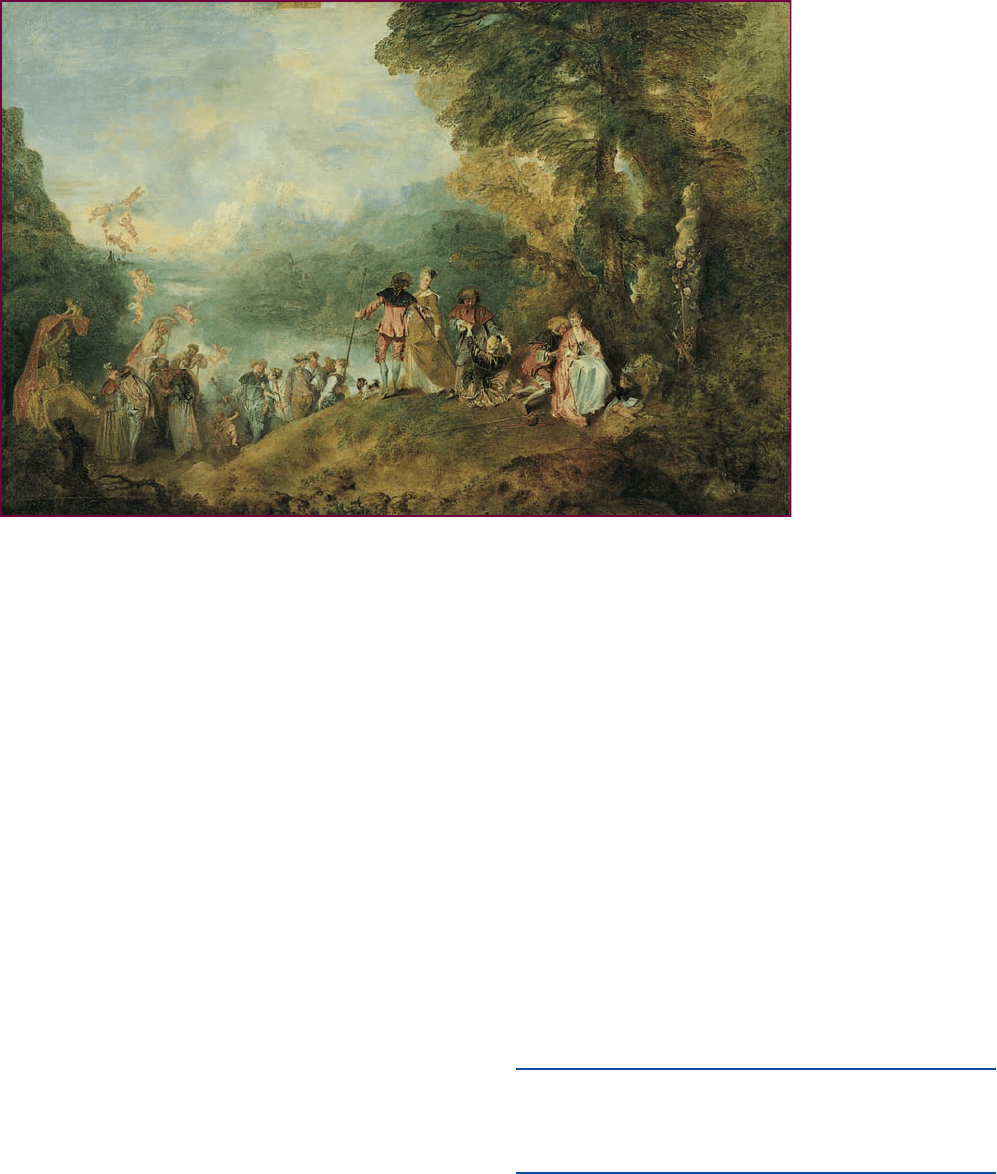

Some of Rococo’ s appeal is evident already in the work

of Antoine Watteau (1684--1721), whose lyr ical views of

aristocratic life, r efined, sensual, and civi lized, with gentle-

men and ladies in elegant dress, revealed a world of upper-

class pleasure and joy. Underneath that exterior, however,

was an element of sadness as the artist revealed the fra-

gility and transitory nature of pleasure, love, and life.

THE RIGHTS OF WOMEN

Mary Wollstonecraft responded to an unhappy

childhood in a large family by seeking to lead an in-

dependent life. Few occupations were available for

middle-class women in her day, but she survived

by working as a teacher, chaperone, and governess to aristo-

cratic children. All the while, she wrote and developed her ideas

on the rights of women. This excerpt is taken from her Vindica-

tion of the Rights of Woman, written in 1792. This work estab-

lished her reputation as the foremost British feminist thinker of

the eighteenth century.

Mary Wollstonecraft, Vindication of the Rights

of Woman

It is a melancholy truth---yet suc h is the bless ed eff ect of civilization---

the most respectable women are the most oppressed; and, unless

they have understandings far superior to the common run of under-

standings, taking in both sexes, they must, from being treated like

contemptible beings, become contemptible. How many women thus

waste life away the prey of discontent, who might have practiced as

physicians, regulated a farm, managed a shop, and stood erect, sup-

ported by their own industry, instead of hanging their heads sur-

charged with the dew of sensibility, that consumes the beauty to

which it at first gave luster. ...

Proud of their weakness, however, [women] must always be

protected, guarded from care, and all the rough toils that dignify the

mind. If this be the fiat of fate, if they will make themselves insignif-

icant and contemptible, sweetly to waste ‘‘life away,’’ let them not ex-

pect to be valued when their beauty fades, for it is the fate of the

fairest flowers to be admired and pulled to pieces by the careless

hand that plucked them. In how many ways do I wish, from the

purest benevolence, to impress this truth on my sex; yet I fear that

they w ill not listen to a truth that dear-bought experience has

brought home to many an agitated bosom, nor willingly resign the

privileges of rank and sex for the privileges of humanity, to which

those have no claim who do not discharge its duties. ...

Would men but generously snap our chains, and be content

with rational fellowship instead of slavish obedience, they would

find us more observant daughters, more affectionate sisters, more

faithful wives, and more reasonable mothers---in a word, better citi-

zens. We should then love them with true affection, because we

should learn to respect ourselves; and the peace of mind of a worthy

man would not be interrupted by the idle vanity of his wife.

Q

What picture does the author paint of the women of her

day? Why are they in such a deplorable state? How does

Wollstonecraft suggest that both women and men are at fault

for the ‘‘slavish’’ situation of females?

TOWARD A NEW HEAVEN AND A NEW EARTH:AN INTELLECTUAL REVOLUTIONINTHEWEST 441

High Culture Historians have grown accustomed to

distinguishing between a civilization’s high culture and its

popular culture. High culture is the literary and artistic

culture of the educated and wealth y ruling classes; popular

culture is the written and un written culture of the masses,

most of which has traditionally been passed down orally.

By the eighteenth century, the two forms were be-

ginning to blend, owing to the expansion of both the

reading public and publishing. Whereas French publish-

ers issued three hundred titles in 1750, about sixteen

hundred were being published yearly in the 1780s. Al-

though many of these titles were still aimed at small

groups of the educated elite, many were also directed to

the new reading public of the middle classes, which in-

cluded women and even urban artisans.

Popular Cultur e The distinguishing characteristic of

popular culture is its collective nature. Group activity was

especially common in the festival, a broad name used to

cover a variety of celebrations: community festivals in

Catholic Europe that celebrated the feast day of the local

patron saint; annual festivals, such as Christmas and

Easter, that go back to medieval Christianity; and the

ultimate festival, Carnival, which was celebrated in the

Mediterranean world of Spain, Italy, and France and in

Germany and Austria as well.

Carnival began after Christmas and lasted until the

start of Lent, the forty-day period of fasting and purifi-

cation leading up to Easter. Because during Lent people

were expected to abstain from meat, sex, and most rec-

reations, Carnival was a time of great indulgence when

heavy consumption of food and drink was the norm. It

was a time of intense sexual activity as well. Songs with

double meanings that would ordinarily be considered

offensive could be sung publicly at this time of year. A

float of Florentine ‘‘keymakers,’’ for example, sang this

ditty to the ladies: ‘‘Our tools are fine, new and useful. We

always carry them with us. They are good for anything. If

you want to touch them, you can.’’

2

Economic Changes

and the Social Order

Q

Focus Question: What changes occurred in the

European economy in the eighteenth century, and to

what degree were these changes reflected in social

patterns?

The eighteenth century in Europe witnessed the begin-

ning of economic changes that ultimately had a strong

impact on the rest of the world.

Antoine Watteau, The Pilgrimage t o Cythera. Antoine Watteau was one of the most gifted

painters in eighteenth-century France. His portrayal of aristocratic life reveals a world of elegance, wealth,

and pleasure. In this painting, Watteau depicts a group of aristocratic pilgrims about to depart the island

of Cythera, where they have paid homage to Venus, the goddess of love.

c

R

eunion des Mus

ees Nationaux/Art Resource, NY

442 CHAPTER 18 THE WEST ON THE EVE OF A NEW WORLD ORDER

New Economic Patterns

Europe’s population began to grow around 1750 and

continued to increase steadily. The total European pop-

ulation was probably around 120 million in 1700, 140

million in 1750, and 190 million in 1790. A falling death

rate was perhaps the most important reason for this

population growth. Of great significance in lowering

death rates was the disappearance of bubonic plague, but

so was diet. More plentiful food and better transportation

of food supplies led to improved nutrition and relief from

devastating famines.

More plentiful food was in part a result of im-

provements in agricultural practices and methods in the

eighteenth century, especially in Britain, parts of France,

and the Low Countries. Food production increased as

more land was farmed, yields per acre increased, and

climate improved. Also important to the increased yields

was the cultivation of new vegetables, including two im-

portant American crops, the potato and maize (Indian

corn). Both had been brought to Europe from the

Americas in the sixteenth century.

In European industry in the eighteenth century,

textiles were the most important product and were still

mostly produced by master artisans in guild workshops.

But in many areas textile production was shifting to the

countryside through the ‘‘putting-out’’ or ‘‘domestic’’

system in which a merchant-capitalist entrepreneur

bought the raw materials, mostly wool and flax, and ‘‘put

them out’’ to rural workers who spun the raw material

into yarn and then wove it into cloth on simple looms.

Capitalist-entrepreneurs sold the finished product, made

a profit, and used it to purchase materials to manufacture

more. This system became known as the cottage industry

because the spinners and weavers did their work on

spinning wheels and looms in their own cottages.

Overseas trade boomed in the eighteenth century.

Some historians speak of the emergence of a true global

economy, pointing to the patterns of trade that interlocked

Europe, Africa, the East, and the Americas (see Map 14.5

in Chapter 14). One such pattern involved the influx of

gold and silver into Spain from its colonial American

empire. Much of this gold and silver made its way to

Britain, France, and the Netherlands in return for manu-

factured goods. Br itish, Dutch, an d French me r chants in

turn used their profits to buy tea, spices, silk, and cotton

goods from China and India to sell in Europe. Another

important source of trading activity involved the planta-

tions of the Western Hemisphere. The plantations were

worked by Afric an sla ve s and pr oduced tobacco, cotton,

coffee, and sugar, all products in demand by Europeans.

Commercial capitalism created enormous prosperity

for some European countries. By 1700, Spain, Portugal,

and the Dutch Republic, which had earlier monopolized

overseas trade, found themselves increasingly over-

shadowed by France and England, which built enor-

mously profitable colonial empires in the course of the

eighteenth century. After the French lost the Seven Years’

War in 1763, Britain emerged as the world’s strongest

overseas trading nation, and London became the world’s

greatest port.

European Society in the Eighteenth Century

The pattern of Europe ’s social organization, first established

in the Middle Ages, continued well into the eighteenth

century. Society was still divided into the traditional

‘‘orders’’ or ‘‘estates’’ determined by heredity.

Because society was still mostly rural in the eighteenth

century, the peasantry constituted the largest social group,

about 85 percent of Europe’s population. There were rather

wide differenc es within this group, however, especially

between free peasants and serfs. In eastern Germany,

eastern Eur ope, and Russia, serfs remained tie d to the lands

of their noble landlords. In contrast, peasants in Britain,

northern Italy, the Low Countries, Spain, most of France,

and some ar eas of western German y wer e largely free.

The nobles, who constituted only 2 to 3 percent of

the European population, played a dominating role in

society. Being born a noble automatically guaranteed a

place at the top of the social order, with all its attendant

privileges and rights. Nobles, for example, were exempt

from many forms of taxation. Since medieval times,

landed aristocrats had functioned as military officers, and

eighteenth-century nobles held most of the important

offices in the administrative machinery of state and

controlled much of the life of their local districts.

Townspeople were still a distinct minority of the total

population except in the Dutch Republic, Britain, and

parts of Italy. At the end of the eighteenth century, about

one-sixth of the French population lived in towns of two

thousand people or more. The biggest city in Europe was

London, with a million inhabitants; Paris was a little

more than half that size.

Man y cities in western and even central E ur ope had a

long tradition of patrician oligarchies that continued to

control their communities by dominating town and city

councils. J ust below the patricians stood an upper crust of

the middle classes: nonnoble officeholders, financiers and

bankers, merchants, wealthy rentiers who lived off their

inv estments, and important professionals, including la w-

yers. Another large urban group consisted of the lower

middle class, made up of master artisans, shopkeepers, and

small traders. Below them were the laborers or working

classes and a large group of unskilled w ork ers who served

as servants, maids, and cooks at pitifully low wages.

ECONOMIC CHANGES AND THE SOCIAL ORDER 443