Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

The poetry of Homer gave an account of the gods

that provided Greek religion with a definite structure.

Over time, most Greeks came to accept a common reli-

gion featuring twelve chief gods and goddesses who were

thought to live on Mount Olympus, the highest moun-

tain in Greece. Among the twelve were Zeus, the chief god

and father of many other gods; Athena, goddess of wis-

dom and crafts; Apollo, god of the sun and poetry;

Aphrodite, goddess of love; and Poseidon, brother of Zeus

and god of the seas and earthquakes.

Greek religion did not have a body of doctrine, nor

did it focus on morality. It offered little or no hope of life

after death for most people. Because the Greeks wanted

the gods to look favorably on their activities, ritual as-

sumed enormous importance in Greek religion. Prayers

were often combined with gifts to the gods based on the

principle ‘‘I give so that you, the gods, will give in return.’’

Yet the Greeks were well aware of the capricious nature of

the gods, who were assigned recognizably human qualities

and often engaged in fickle or even vengeful behavior

toward other deities or human beings.

Festivals also developed as a way to honor the gods

and goddesses. Some of these (the Panhellenic celebra-

tions) came to ha v e significanc e for all Greeks and were

held at special locations, such as those dedicated to the

worship of Zeus at Olympia or to Apollo at Delphi. The

great festivals featured numerous events held in honor of

the gods, including athletic competitions to which all

Greeks were invited. The first such games were held at the

Olympic festival in 776

B.C.E. and then held every four years

thereafter to honor Zeus. Initially, the Olympic contests

consisted of foot races and wrestling, but later boxing,

javelin throwing, and various other contests were added.

As another practical side of Greek religion, Greeks

wanted to know the will of the gods. To do so, they made

use of the oracle, a sacred shrine dedicated to a god or

goddess who revealed the future. The most famous was

the oracle of Apollo at Delphi, located on the side of

Mount Parnassus, overlooking the Gulf of Corinth. At

Delphi, a priestess, thought to be inspired by Apollo,

listened to questions. Her responses were then interpreted

by the priests and given in verse form to the person asking

questions. Representatives of states and individuals trav-

eled to Delphi to consult the oracle of Apollo. Responses

were often enigmatic and at times even politically moti-

vated. Croesus, the king of Lydia in Asia Minor who was

known for his incredible wealth, sent messengers to the

oracle at Delphi, asking ‘‘whether he shall go to war with

the Persians.’’ The oracle replied that if Croesus attacked

the Persians, he would destroy a mighty empire. Over-

joyed to hear these words, Croesus made war on the

Persians but was crushed by his enemy. A mighty empire

was destroyed---Croesus’ own.

Daily Life in Classical Athens

The polis was, above all, a male community: only adult

male citizens took part in public life. In Athens, this meant

the exclusion of women, slaves, and foreign residents, or

roughly 85 per c ent of the popul ation of Attica. There we r e

perhaps 150,000 citizens of Athens proper, of whom about

43,000 were adult males who exercised political power.

Resident foreigners, who numbered about 35,000, received

the protection of the laws but were also subject to some of

the responsibilities of citizens, including military service

and the funding of festivals. The remaining social group,

the slaves, numbered around 100,000. Most slaves in

Athens worked in the home as cooks and maids or worked

in the fields. Some were owned by the state and worked on

public construction projects.

The Athenian economy was largely based on agri-

culture and trade. Athenians grew grains, vegetables, and

fruit for local consumption. Grapes and olives were cul-

tivated for wine and olive oil, which were used locally and

also exported. The Athenians raised sheep and goats for

wool and dairy products. Because of the size of the

population and the lack of abundant fertile land, Athens

had to import 50 to 80 percent of its grain, a staple in the

Athenian diet. Trade was thus very important to the

Athenian economy.

Family and Relationships The family was a central

institution in ancient Athens. It was composed of hus-

band, wife, and children, along with other dependent

relatives and slaves who were part of the economic unit.

The family’s primary social function was to produce new

citizens.

Women were citizens who could participate in most

religious cults and festivals, but they were otherwise ex-

cluded from public life. They could not own property

beyond personal items and always had a male guardian.

An Athenian woman was expected to be a good wife. Her

foremost obligation was to bear children, especially male

children who would preserve the family line. Moreover, a

wife was to take care of her family and her house, either

doing the household work herself or supervising the

slaves who did the actual work (see the box on p. 95).

Male homosexuality was also a prominent feature of

Athenian life. The Greek homosexual ideal was a rela-

tionship between a mature man and a young male. Al-

though the relationship was frequently physical, the

Greeks also viewed it as educational. The older male (the

‘‘lover’’) won the love of his ‘‘beloved’’ through his value as

a teacher and the devotion he demonstrated in training his

charge. In a sense, this love relationship was seen as a way

of initiating young males into the male world of political

and military dominance. The Greeks did not feel that

94 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

the coexistence of homosexual and heterosexual predi-

lections created any special problems for individuals or

their society.

The Rise of Macedonia and the

Conquests of Alexander

Q

Focus Question: How was Alexander the Great able to

amass his empire, and what was his legacy?

While the Greek city-states were caught up in fighting

each other, a new and ultimately powerful kingdom to

their north was emerging in its own right. To the Greeks,

the Macedonians were little more than barbarians, a

mostly rural folk organized into tribes rather than city-

states. Not until the late fifth century

B.C.E. did Macedonia

emerge as a kingdom of any importance. But when Philip

II (359--336

B.C.E.) came to the throne, he built an effi-

cient army and turned Macedonia into the strongest

power in the Greek world---one that was soon drawn into

the conflicts among the Greeks.

The Athenians at last took notice of the new con-

tender. Fear of Philip led them to ally with a number of

other Greek states and confront the Macedonians at the

Battle of Chaeronea, near Thebes, in 338

B.C.E. The

Macedonian army crushed the Greeks, and Philip quickly

gained control of all Greece, bringing an end to the

freedom of the Greek city-states. He insisted that the

Greek states form a league and then cooperate with him

in a war against Persia. Before Philip could undertake his

invasion of Asia, however, he was assassinated, leaving the

task to his son Alexander.

Alexander the Great

Alexander was only twenty when he became king of

Macedonia. In many ways, he had been prepared to rule

by his father, who had taken Alexander along on military

campaigns and had put him in command of the cavalry at

Chaeronea. After his father’s assassination, Alexander

moved quickly to assert his authority, securing the

Macedonian frontiers and quashing a rebellion in Greece.

He then turned to his father’s dream, the invasion of the

Persian Empire.

Alexander’s Conquests Certainly, Alexander was tak-

ing a chance in attacking Persia, which was still a strong

state. In the spring of 334

B.C.E., Alexander ente r ed Asia

Minor with an army of some 37,000 men. About half were

HOUSEHOLD MANAGEMENT AND THE ROLE OF THE ATHENIAN WIFE

In Athens in the fifth century B.C.E., a woman’s

place was in the home. She had two major respon-

sibilities: the bearing and raising of children and

the management of the household. In this dialogue

on estate management, Xenophon relates the advice of an

Attican gentleman on how to train a wife.

Xenophon, Oeconomicus

[Ischomachus addresses his new wife.] For it seems to me, dear,

that the gods with great discernment have coupled together male

and female, as they are called, chiefly in order that they may form a

perfect partnership in mutual serv ice. For, in the first place, that the

various species of living creatures may not fail, they are joined in

wedlock for the production of children. Secondly, offspring to sup-

port them in old age is provided by this union, to human beings, at

any rate. Thirdly, human beings live not in the open air, like beasts,

but obv iously need shelter. Nevertheless, those who mean to win

stores to fill the covered place, have need of someone to work at the

open-air occupations; since plowing, sowing, planting, and grazing

are all such open-air employments; and these supply the needful

food. ... For he made the man’s body and mind more capable of

enduring cold and heat, and journeys and campaigns; and therefore

imposed on him the outdoor tasks. To the woman, since he has

made her body less capable of such endurance, I take it that God

has assigned the indoor tasks. And knowing that he had created in

the woman and had imposed on her the nourishment of the infants,

he meted out to her a larger portion of affection for newborn babes

than to the man. ... Now since we know, dear, what duties have

been assigned to each of us by God, we must endeavor, each of us,

to do the duties allotted to us as well as possible. ...

Your duty will be to remain indoors and send out those ser-

vants whose work is outside, and superintend those who are to

work indoors, and to receive the incomings, and distribute so much

of them as must be spent, and watch over so much as is to be kept

in store, and take care that the sum laid by for a year be not spent

in a month. And when wool is brought to you, you must see that

cloaks are made for those that want them. You must see too that

the dry corn is in good condition for making food. One of the

duties that fall to you, however, will perhaps seem rather thankless:

you will have to see that any servant who is ill is cared for.

Q

What does this selection from Xenophon tell you about

the role of women in the Athenian household? How do these

requirements compare with those applied in ancient India and

ancient China?

THE RISE OF MAC E D O N IA AN D T H E CONQUESTS OF ALEXANDER 95

Macedonians, the rest Greeks and other allies. The cavalry,

which would play an important role as a strike force,

numbered about 5,000. By the following spring, the entire

western half of Asia Minor was in Alexander’s hands (see

Map 4.2). Meanwhile, the Persian king, Darius III, mo-

bilized his forces to stop Alexander’s army, but the sub-

sequent Battle of Issus resulted in yet another Macedonian

success. Alexander then turned south, and by the winter of

332, Syria, Palestine, and Egypt were under his control.

In 331

B.C.E., Alexander turned east and fought a

decisive battle with the Persians at Gaugamela, northwest

of Babylon. After his victory, Alexander entered Babylon

and then proceeded to the Persian capitals at Susa and

Persepolis, where he took possession of vast quantities of

gold and silver. By 330, Alexander was again on the

march, pursuing Darius. After Darius was killed by one of

his own men, Alexander took the title and office of the

Great King of the Persians. Over the next three years, he

traveled east and northeast, as far as modern Pakistan. By

the summer of 327

B.C.E., he had entered India, which at

that time was divided into a number of warring states. In

326

B.C.E., Alexander and his armies arrived in the plains

of northwestern India. At the Battle of the Hydaspes

River, Alexander won a brutally fought battle (see the box

on p. 98). When Alexander made clear his determination

to march east to conquer more of India, his soldiers,

weary of campaigning year after year, mutinied and re-

fused to go further. Alexander returned to Babylon, where

he planned more campaigns. But in June 323

B.C.E.,

weakened by wounds, fever, and probably excessive al-

cohol, he died at the age of thirty-two.

The Legacy of Alexander Alexander is one of the most

puzzling great figures in history. Historians relying on the

same sources give vastly different pictures of him. Some

portray him as an idealistic visionary and others as a

ruthless Machiavellian. How did Alexander the Great

view himself? We know that he sought to imitate Achilles,

the warrior-hero of Homer’s Iliad. Alexander kept a copy

of the Iliad---and a dagger---under his pillow. He also

claimed to be descended from Heracles, the Greek hero

who came to be worshiped as a god.

Regar dless of his ideals, motives, or views about him-

self, one fact stands out: Alexander ushered in a new age,

the Hellenistic era. The word Hellenistic is derived from a

Greek word meaning ‘‘to imitate Greeks.’’ It is an appro-

priate term to describe an age that saw the extension of the

Greek language and ideas to the non-Gr eek world of the

Middle East. Alexander’ s destruction of the P ersian mon-

arch y opened up opportunities for Greek engineers, in-

tellectuals, merchants, administrators, and soldiers. Those

who followed Alexander and his suc cessors participated

in a new political unity based on the principle of

mo narchy. His vision of empire no doubt inspired the

Romans, who were the ultimate heirs of Alexander’s

political legacy.

But Alexander also left a cultural le gacy. As a result

of his conqu ests, Greek language, art, architecture, and

literature spread th roughout th e Middle East. The urban

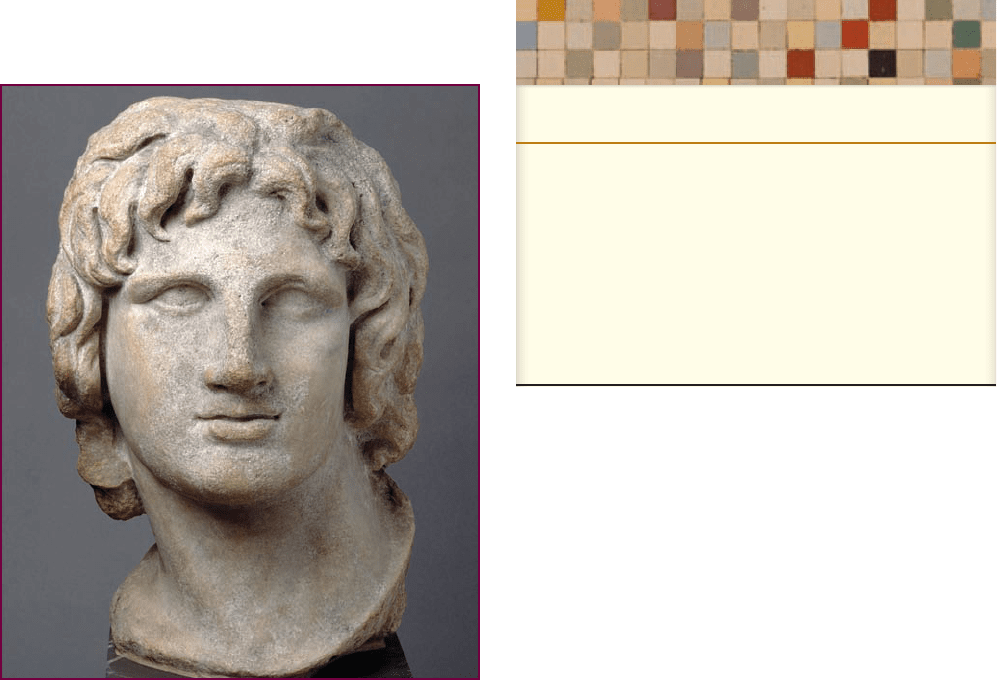

Alexander the Great. This marble head of Alexander the Great was

made in the second or first century

B.C.E. The long hair and tilt of his head

reflect the description of Alexander in the literary sources of the time.

Alexander claimed to be descended from Heracles, a Greek hero worshiped

as a god, and when he proclaimed himself pharaoh of Egypt, he gained

recognition as a living deity. It is reported that one statue, now lost,

showed Alexander gazing at Zeus. At the base of the statue were the words

‘‘I place the earth under my sway; you, O Zeus, keep Olympus.’’

CHRONOLOGY

The Rise of Macedonia and the

Conquests of Alexander

Reign of Philip II 359--336

B.C.E.

Battle of Chaeronea; conquest of Greece 338

B.C.E.

Reign of Alexander the Great 336--323

B.C.E.

Alexander’s invasion of Asia 334

B.C.E.

Battle of Gaugamela 331

B.C.E.

Fall of Persepolis 330

B.C.E.

Alexander’s entry into India 327

B.C.E.

Death of Alexander 323

B.C.E.

c

British Museum, London/HIP/Art Resource, NY

96 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

centers of the Hellenistic age, many fou nded by Alex-

ander and his successors, became springboards f or the

diffusion of Greek culture. While the Greeks spread their

culture in the East, they were also inevitably influenced

by Eastern ways. Thus, Alexander’s legacy was one of the

earmarks of the Hellenistic era: the clas h and fusion of

different cultures.

The World of the Hellenistic

Kingdoms

Q

Focus Question: How did the political and social

institutions of the Hellenistic world differ from those

of Classical Greece?

The united empire that Alexander assembled through his

conquests crumbled soon after his death. All too soon,

the most important Macedonian generals were engaged in

a struggle for power, and by 300

B.C.E., four Hellenistic

kingdoms had emerged as the successors to Alexander

(see Map 4.3 on p. 100): Macedonia under the Antigonid

dynasty, Syria and the East under the Seleucids, the

Attalid kingdom of Pergamum in western Asia Minor,

and Egypt under the Ptolemies. All were eventually

conquered by the Romans.

Political Institutions and the Role of Cities

Alexander had planned to fuse Macedo nians, Greeks,

and easterners in his new empire by using Persians as

officials and encouraging his soldiers to marry native

women. The Hellenistic monarchs wh o succeeded him,

however, relied only on Greeks and Macedonians to

form the new ruling cla ss. Those easterners who did

advance to important government posts had learned

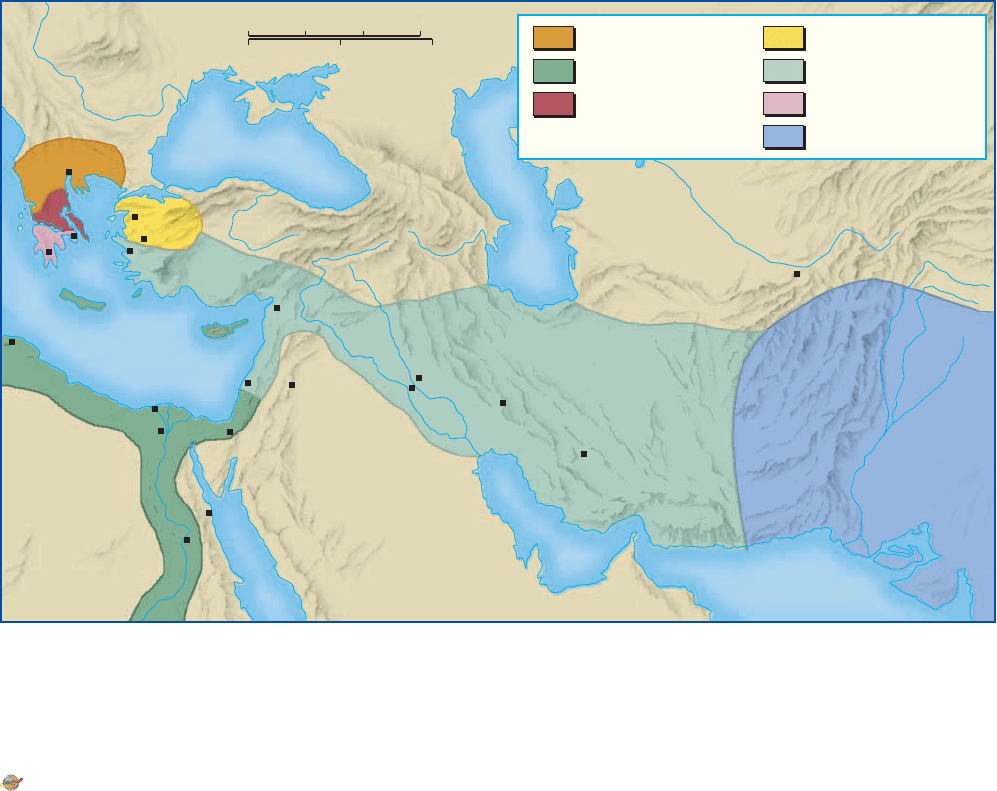

MAP 4.2 The Conquests of Alexander t he Grea t. In just twelve years, Alexander the

Great conquered vast territories. Dominating lands from west of the Nile to east of the Indus,

he brought the Persian Empire, Egypt, and much of the Middle East under his control and laid

the foundations for the Hellenistic world.

Q

Appr oximately how far did Alexander and his troops travel during those twelve years,

and what kinds of terrain did they encounter on t heir journey?

THE WORLD OF THE HELLENISTIC KINGDOMS 97

Greek, the language in which all governm ent business

was transacted. The Greek ruling class was determined

to maintain its privileged position.

Alexander had founded numerous new cities and

military settlements, and Hellenistic kings did likewise.

The new populati on centers varied considerably in size

and importance. Military settlements, intended to main-

tain order, might consist of only a few hundred men. The

new independent cities attracted thousands of people.

One of these new cities, Alexandria in Egypt, had become

the largest city in the Mediterranean region by the first

century

B.C.E.

Hellenistic rul ers encouraged a massive spread of

Greek colonists to the Middle East. Greeks and Mace-

donians provided not on ly recruits for the army but also

a pool o f civilian administrators and workers who

contributed to economic development. Even architect s,

engineers, dramatists, and actors were in demand in the

new Greek cities. Many Greeks and Macedonians were

quic k to see the adv antages of moving to the new urban

centers and gladly sought their fortunes in the Middle

East. The Greek cities of the Hellenistic era became the

chief agents in the spread of Greek culture in the Middle

East---as far east, in fact, as modern Afghanistan and

India.

Culture in the Hellenistic World

Although the Hellenistic kingdoms encompassed vast

territories and many diverse peoples, the Greeks provided

a sense of unity as a result of the diffusion of Greek culture

throughout the Hellenistic world. The Hellenistic era was

a period of considerable cultural accomplishment in many

areas, especially science and philosophy. Although these

achievements occurred throughout the Hellenistic world,

certain centers, especially the great city of Alexandria,

stood out. Alexandria became home to poets, writers,

philosophers, and scientists---scholars of all kinds. The li-

brary there became the largest in ancient times, with more

than 500,000 scrolls.

The founding of new cities an d the rebuilding of old

ones provided nu merous opportunities for Greek archi-

tects and sculptors. The Hellenistic monarchs were par-

ticularly eager to spend their money to beautify and adorn

the cities within their states. The buildings of the Greek

homeland---gymnasiums, baths, theaters, and temples---

lined the str eets of these cities.

Both Hellenistic monarchs and rich citizens

pa troniz ed sculptors. Hellenistic sculptors traveled

th roughout this world, attracted by t he material re-

wa rds offered by wealthy patrons. These sculptors

ALEXANDER MEETS AN INDIAN KING

In his campaigns in India, Alexander fought a

number of difficult battles. At the Battle of the

Hydaspes River, he faced a strong opponent in the

Indian king Porus. After defeating Porus, Alexander

treated him with respect, according to Arrian, Alexander’s

ancient biographer.

Arrian, The Campaigns of Alexander

Throughout the action Porus had proved himself a man indeed, not

only as a commander but as a soldier of the truest courage. When he

saw his cavalry cut to pieces, most of his infantry dead, and his ele-

phants killed or roaming riderless and bewildered about the field, his

behavior was very different from that of the Persian King Darius: un-

like Darius, he did not lead the scramble to save his own skin, but so

long as a single unit of his men held together, fought bravely on. It

was only when he was himself wounded that he turned the elephant

on which he rode and began to withdraw. ... Alexander, anxious to

save the life of this great soldier, sent ...[to him] an Indian named

Meroes, a man he had been told had long been Porus’s friend. Porus

listened to Meroes’s message, stopped his elephant, and dismounted;

he was much distressed by thirst, so when he had revived himself by

drinking, he told Meroes to conduct him with all speed to Alexander.

Alexander, informed of his approach, rode out to meet

him. ... When they met, he reined in his horse, and looked at his

adversary with admiration: he was a magnificent figure of a man,

over seven feet high and of great personal beauty; his bearing had

lost none of its pride; his air was of one brave man meeting another,

of a king in the presence of a king, with whom he had fought hon-

orably for his kingdom.

Alexander was the first to speak. ‘‘What,’’ he said, ‘‘do you wish

that I should do with you?’’ ‘‘Treat me as a king ought,’’ Porus is

said to have replied. ‘‘For my part,’’ said Alexander, pleased by his

answer, ‘‘your request shall be granted. But is there not something

you would wish for yourself? Ask it.’’ ‘‘Everything,’’ said Porus, ‘‘is

contained in this one request.’’

The dignity of these words gave Alexander even more pleasure,

and he restored to Porus his sovereignty over his subjects, adding to

his realm other territory of even greater extent. Thus he did indeed

use a brave man as a king ought, and from that time forward found

him in every way a loyal friend.

Q

What do we learn from Arrian’s account about Alexander’s

military skills and Indian methods of fighting?

98 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

maintained the technical skill of the Classical period,

but they moved away from the idealism of fifth-century

Classicism to a more emotional and realistic art, which

is ev ident in numerous statues of old women, drunks,

and little children at play. Hellenistic artistic styles even

affected ar tists in India (see the comparative illustration

on p. 101).

A Golden Age of Science The Hellenistic era wit-

nessed a more conscious separation of science from

philosophy. In Classical Greece, what we would call the

physical and life sciences had been divisions of philo-

sophical inquiry. Nevertheless, by the time of Ar istotle,

the Greeks had already established an impor tant prin-

ciple of scientific investigat ion---empirical research or

systematic observati on as the basis for generalization. I n

the Hellenistic age, the sciences tended to be studied in

their own right.

By far the most famous scientist of the Hellenistic

period was Archimedes (287--212

B.C.E.). Archimedes

FILM & HISTORY

A

LEXANDER (2004)

Alexander is the product of director Oliver Stone’s lifelong

fascination with Alexander, the king of Macedonia who conquered

the Persian Empire in the fourth century

B.C.E. and launched the

Hellenistic era. Stone’s epic film about Alexander’s short life cost

$150 million, which resulted in an elaborate and in places visually

beautiful film. Narrated by the aging Ptolemy (Anthony Hopkins),

Alexander’s Macedonian general who took control of Egypt after his

death, the film tells the story of Alexander (Colin Farrell) through a

mix of battle scenes, scenes showing the progress of Alexande r and

his army through the Middle East and India, and flashbacks to his

early years. Stone portrays Alexander’s relationship with his mother,

Olympias (Angelina Jolie), as instrumental in his early development

while also focusing on his rocky relationship with his father, King

Philip II (Val Kilmer). The movie focuses on the major battle at

Gaugamela in 331

B.C.E. where the Persian leader Darius was forced

to flee, and then follows Alexander as he conquers the rest of the

Persian Empire and continues east into India. After his troops

threaten to mutiny, Alexander returns to Babylon, where he dies

on June 10, 323

B.C.E.

The enormous amount of money spent on the film enabled

Stone to achieve a stunning visual spectacle, but as history, the film

leaves mu ch to be desired. The character of Ale xander is ne v er devel-

oped in depth. At times he is shown as a weak ruler plagued by

doubts about his decisions. Though he often seems obsessed by a de-

sire for glory, Alexander is also portrayed as an idealistic leader who

believed that the people he conquered wanted chang e, that he was

‘‘freeing the people of the world,’’ and that Asia and Europe would

grow together into a single entity. But was Alexander an idealistic

dreamer, as Stone apparently believes, or was he a military leader who ,

following the dictum that ‘‘fortune favors the bold,’’ ran roughshod

over the wishes of his soldiers in order to fol low his dream and was

responsible for mass slaughter in the process? The latter is a perspec-

tive that Stone glosses over, but Ptolemy, at least, probably expresses

the more realistic not ion th at ‘‘none of us believed in his dream.’’

The movie also does not elaborat e on Alexander’s wish to

be a god. Certainly, Alexander aspired to divine honors; at one

point he sent instructions to the Greek cities to ‘‘vote him a god.’’

Stone’s por trayal of Alexander is perhaps most realistic in present-

ing Alexander’s drinking binges and his bisexuality, which was

common in the Greco-Roman world. His marriage to Roxane

(Rosario Dawson), daughter of a Bactrian noble, is shown, as well

as his love for his lifelong companion, Hephaestion (Jared Leto),

and his sexual relationship with the Persian male slave Bagoas

(Francisco Bosch).

The film contains a num ber of inaccurate historical details.

Alexander’s first encounters with the Persian royal princesses

and Bagoas did not occur when he entered Babylon for the first

time. Alexander did not kill Cleitas in India, and he was not

wounded in In dia at the Battle of Hydaspes but at the siege of

Malli. Specialists in Persian histor y have also argued that the

Persian military forces were much more disciplined than

depicted in the film.

Alexander (Colin Farrell) reviewing his troops before the Battle of

Gaugamela.

Warner Bros./The Kobal Collection/Jaap Buitendijk

THE WORLD OF THE HELLENISTIC KINGDOMS 99

was especially important for his work on the geometry

of spheres and cylinders and for e stablishing the value

of the mathematical constant pi. Archimedes was also a

practical inven tor. He may have devised the so-called

Archimedean screw used to pump water out of mines

and to lift irrigation water. During the Roman siege of

his native city of Syracuse, he constructed a number of

devices to thwart the attackers. Archimedes’ accom-

plishments inspired a wealth of semilegendary stories.

Supposedly, he discovered specific gravity by observing

the water he displaced in his ba th an d became so excited

by his realization that he jumped out of the water and

ran home naked, shouting , ‘‘Eureka!’’ (‘‘I have found

it’’). He is said to have emphasized the importa nce of

levers by proclaiming to the king of Sy racuse: ‘‘Give me

a lever and a place to stand on, and I w ill move the

earth.’’ The king was so impressed that he encouraged

Archimedes to lower his sights and build defensive

weapons instead.

Philosophy While Alexa ndria b ecame the renowne d

cultural center of the Hellenistic world, Athens re-

mained the prime center for philosophy. Even after

Alexander the Great, the home of Socrates, Plato, and

Aristotle continued to attract the most illustrious

philosophers from the Greek world, who chose to

establish their schools there. New schools of philo-

sophical thought reinforced Athens’s reputation as a

philosophical center.

Epicurus (341--270

B.C.E.), the founder of Epicure-

anism, established a school in Athens near the end of the

fourth century

B.C.E. Epicurus believed that human beings

Aral

Sea

Caspian

Sea

Black Sea

Red

Sea

M

e

d

i

t

e

r

r

a

n

e

a

n

S

e

a

Arabian

Sea

P

e

r

s

i

a

n

G

u

l

f

Aegean

Sea

I

n

d

u

s

R

.

N

i

l

e

R

.

T

i

g

r

i

s

R

.

E

u

p

h

r

a

t

e

s

R

.

H

a

l

y

s

R

.

J

a

x

a

r

t

e

s

R

i

v

e

r

O

x

u

s

R

.

H

y

d

a

s

p

e

s

R

.

H

y

p

h

a

s

i

s

R

.

D

a

n

u

b

e

R

.

T

a

u

r

u

s

M

t

s

.

C

a

u

c

a

s

u

s

M

t

s

.

Arabian

Desert

Sahara

B

a

l

k

a

n

M

t

s

.

THRACE

INDIA

Pergamum

Ephesus

Susa

Persepolis

Alexandria

Rhodes

Cyprus

Tyre

Damascus

Petra

Berenice

Coptos

Babylon

Seleucia

Sparta

Athens

Pella

Memphis

Antioch

Bactra

Cyrene

Crete

Sardis

Z

a

gr

o

s

M

t

s.

0 300 600 Miles

0 300 600 900 Kilometers

Seleucid kingdom

Ptolemaic kingdom

Antigonid kingdom

Aetolian League

Mauryan Empire

Pergamene kingdom

Achaean League

MAP 4.3 The World of the Hell enistic Kingdoms. Alexander died unexpectedly at the age

of thirty-two and did not designate a successor. On his death, his generals struggled for power,

eventually establishing four monarchies that spread Hellenistic culture and fostered trade and

economic development.

Q

Based solely on the map, which kingdom do you think was the most prosperous and

powerful? Wh y?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www.c engage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

100 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

were free to follow self-interest as a basic motivating

force. Happiness was the goal of life, and the means to

achieve it was the pursuit of pleasure, the only true good.

But pleasure was not meant in a physical, hedonistic sense

(which is what our word epicurean has come to mean)

but rather referred to freedom from emotional turmoil

and worry. To achieve this kind of pleasure, one had to

free oneself from public affairs and politics. But this was

not a renunciation of all social life, for

to Epicurus, a life could be complete

only when it was based on friendship.

Epicurus’ own life in Athens was an

embodiment of his teachings. He and

his friends created their own private

community where they could pursue

their ideal of true happiness.

Another school of thought was

Stoicism, which became the most

popular philosophy of the Hellenistic

world and later flourished in the Ro-

man Empire as well. It was the prod-

uct of a teacher named Zeno (335--

263

B.C.E.), who came to Athens and

began to teach in a public colonnade

known as the Painted Portico (the

Stoa Poikile---hence Stoicism). Like

Epicureanism, Stoicism was con-

cerned with how individuals find

happiness. But Stoics took a radically

different approach to the problem. To

them, happiness, the supreme good,

could be found only by living

in harmony with the divine w ill,

by which people gained inner peace.

Life’s problems could n ot disturb

these people, and they could bear

whatever life offered (hence our word

stoic). Unlike Epicureans, Stoics did

not believe in the need to separate

oneself from the world and politics.

Public ser v ice was regarded as noble,

and the real Stoic was a good citizen

and could even be a good government

official.

Both Epicureanism and Stoicism

focused primarily on human happi-

ness, and their popularity would

suggest a fundamental change in the

Greek lifestyle. In the Classical Greek

world, the happiness of individuals

and the meaning of life were closely

associated with the life of the polis.

One found fulfillment in the com-

munity. In the Hellenistic kingdoms, the sense that one

could find fulfillment through life in the polis had

weakened. People sought new philosophies that offered

personal happiness, and in the cosmopolitan world of

the Hellenistic states, with their mixtures of peoples, a

new openness to thoug hts of universality could also

emerge. For some people, Stoicism embodied this larger

sense of communit y.

COMPARATIVE ILLUSTRATION

Hellenistic Sculpture and a Greek-Style Buddha. Greek architects

and sculptors were highly valued throughout the Hellenistic world.

Shown on the left is a terra-cotta statuette of a draped young woman,

made as a tomb offering near Thebes, probably around 300

B.C.E. The incursion

of Alexander into the western part of India resulted in some Greek cultural

influences there, especially during the Hellenistic era. During the first century

B.C.E., Indian sculptors in Gandhara, which today is part of Pakistan, began to

create statues of the Buddha. The Buddhist Gandharan style combined Indian and

Hellenistic artistic traditions, which is evident in the stone sculpture of the

Buddha on the right. Note the wavy hair topped by a bun tied with a ribbon,

also a feature of earlier statues of Greek deities. This Buddha is also wearing a

Greek-style toga.

Q

How would you explain the impact of Hellenistic sculpture on India?

What would you conclude from this example about the influence of

conquerors on conquered people?

c

The Art Archive/Gianni Dagli Orti

c

Borromeo/Art Resource, NY

THE WORLD OF THE HELLENISTIC KINGDOMS 101

TIMELINE

1500 B.C.E. 1000 B.C.E.

750 B.C.E. 500 B.C.E. 250 B.C.E. 100 B.C.E.

Mycenaean Greece

Lycurgan

reforms

in Sparta

Homer Parthenon Flourishing of Hellenistic science

Greek drama (Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides)

Great Peloponnesian War

Battle of

Marathon

Conquests of Alexander the Great

Age of Expansion

(Archaic Age)

Hellenistic kingdoms

Classical Age

Plato and Aristotle

CONCLUSION

UNLIKE THE GREAT CENTRALIZED EMPIRES of the

Persians and the Chinese, ancient Greece consisted of a large

number of small, independent city-states, most of which had only

a few thousand inhabitants. Yet these ancient Greeks created a

civilization that was the fountainhead of Western culture. Socrates,

Plato, and Aristotle established the foundations of Western

philosophy. Western literary forms are largely derived from Greek

poetry and drama. Greek notions of harmony, proportion, and

beauty have remained the touchstones for all subsequent Western

art. A rational method of inquiry, so important to modern science,

was conceived in ancient Greece. Many political terms are Greek in

origin, and so are concepts of the rights and duties of citizenship,

especially as they were conceived in Athens, the world’s first great

democracy. Especially during their Classical period, the Greeks

raised and debated the fundamental questions about the purpose of

human existence, the structure of human society, and the nature of

the universe that have concerned thinkers ever since.

Yet despite all these achievements, there remains an element of

tragedy about Greek civilization. Notwithstanding their brilliant

accomplishments, the Greeks were unable to rise above the divisions

and rivalries that caused them to fight each other and undermine

their own civilization. Of course, their cultural contributions have

outlived their political struggles. And the Hellenistic era, which

emerged after the Greek city-states had lost their independence,

made possible the spread of Greek ideas to larger areas.

During the Hellenistic period, Greek culture extended

throughout the Middle East and made an impact wherever it was

carried. Although the Hellenistic world achieved a degree of

political stability, by the late third century

B.C.E. signs of decline

were beginning to multiply. Few Greeks realized the danger to the

Hellenistic world of the growing power of Rome. But soon the

Romans would inherit Alexander’s empire and Greek culture, and

we now turn to them to try to understand what made them such

successful conquerors.

102 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

SUGGESTED READING

General Works G ood general introductions to Greek history

include T. R. Martin, Ancient Greece (New Haven, Conn., 1996);

P. Cartledge, The Cambridge Illustrated History of Ancient Greece

(Cambridge, 1998); and S. B. Pomeroy et al., Ancient Greece:

A Political, Social, and Cultural History (New York, 1998).

Early Greek History Early Greek history is examined in

J. Hall, History of the Archaic Greek World, c. 1200--479

B.C.

(London, 2006). On colonization, see J. Boardman, The Greeks

Overseas, rev. ed. (Baltimore, 1980). On tyranny, see J. F. McGlew,

Tyranny and Political Culture in Ancient Greece (Ithaca, N.Y.,

1993). On Sparta, see P. Cartledge, The Spartans (New York, 2003).

On early Athens, see R. Osborne, Demos (Oxford, 1985). The

Persian Wars are examined in P. Green, The Greco-Persian Wars

(Berkeley, Calif., 1996).

Classical Greece A general history of Classical Greece can be

found in P. J. Rhodes, A History of the Greek Classical World,

478--323

B.C. (London, 2006). There is also a good collection of

essays in P. J. Rhodes, ed., Athenian Democracy (New York, 2004).

On the development of the Athenian empire, see M. F. McGregor,

The Athenians and Their Empire (Vancouver, 1987). The best way

to examine the Great Peloponnesian War is to read the work of

Thucydides, History of the Peloponnesian War, trans. R. Warner

(Harmondsworth, England, 1954). Recent accounts include J. F. F.

Lazenby, The Peloponnesian War (New York, 2004), and D. Kagan,

The Peloponnesian War (New York, 2003).

Greek Culture For a history of Greek art, see M. Fullerton,

Greek Art (Cambridge, 2000). On sculpture, see A. Stewart, Greek

Sculpture: An Exploration (New Haven, Conn., 1990). On Greek

drama, see the general work by J. De Romilly, A Short History of

Greek Literature (Chicago, 1985). On Greek philosophy, a detailed

study is available in W. K. C. Guthrie, A History of Greek

Philosophy, 6 vols. (Cambridge, 1962--1981). On Greek religion, see

J. N. Bremmer, Greek Religion (Oxford, 1994).

Family and Women On the family and women, see C. B.

Patterson, The Family in Greek History (New York, 1998);

P. Brule, Women of Ancient Greece, trans. A. Nevill (Edinburgh,

2004); and S. Blundell, Women in Ancient Greece (Cambridge,

Mass., 1995).

General Works on the Hellenistic Era For a general

introduction, see P. Green, The Hellenistic Age: A Short History

(New York, 2007). The best general surveys of the Hellenistic era are

F. W. Walbank, The Hellenistic World, rev. ed. (Cambridge, Mass.,

2006), and G. Shipley, The Greek Worl d After Alexander , 323--30

B.C.

(New York, 2000). There are considerable differences of opinion on

Alexander the Great. Good biogr aphies include P. Cartledge,

Alexander the Great (New York, 2004); G. M. Rogers, Alexander

(NewYork,2004);andP. Green, Alexander of Macedon (Berkeley,

Calif., 19 91).

Hellenistic Monarchies The various Hellenistic monarchies

can be examined in N. G. L. Hammond and F. W. Walbank, A

History of Macedonia, vol. 3, 336--167

B.C. (Oxford, 1988);

S. Sherwin-White and A. Kuhrt, From Samarkand to Sardis: A

New Approach to the Seleucid Empire (Berkeley, Calif., 1993); and

N. Lewis, Greeks in Ptolemaic Eg ypt (Oxford, 1986). See also the

collection of essays in C. Habicht, Hellenistic Monarchies (Ann

Arbor, Mich., 2006).

Hellenistic Culture For a general introduction to Hellenistic

culture, see J. Onians, Art and Thought in the Hellenistic Age

(London, 1979). The best general survey of Hellenistic philosophy

is A. A. Long, Hellenistic Philosophy: Stoics, Epicureans, Skeptics,

2nd ed. (London, 1986). A superb work on Hellenistic science is

G. E. R. Lloyd, Greek Science After Aristotle (London, 1973).

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Cr itical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION 103