Duiker W.J., Spielvogel J.J. The Essential World History. Volume 1: To 1800

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

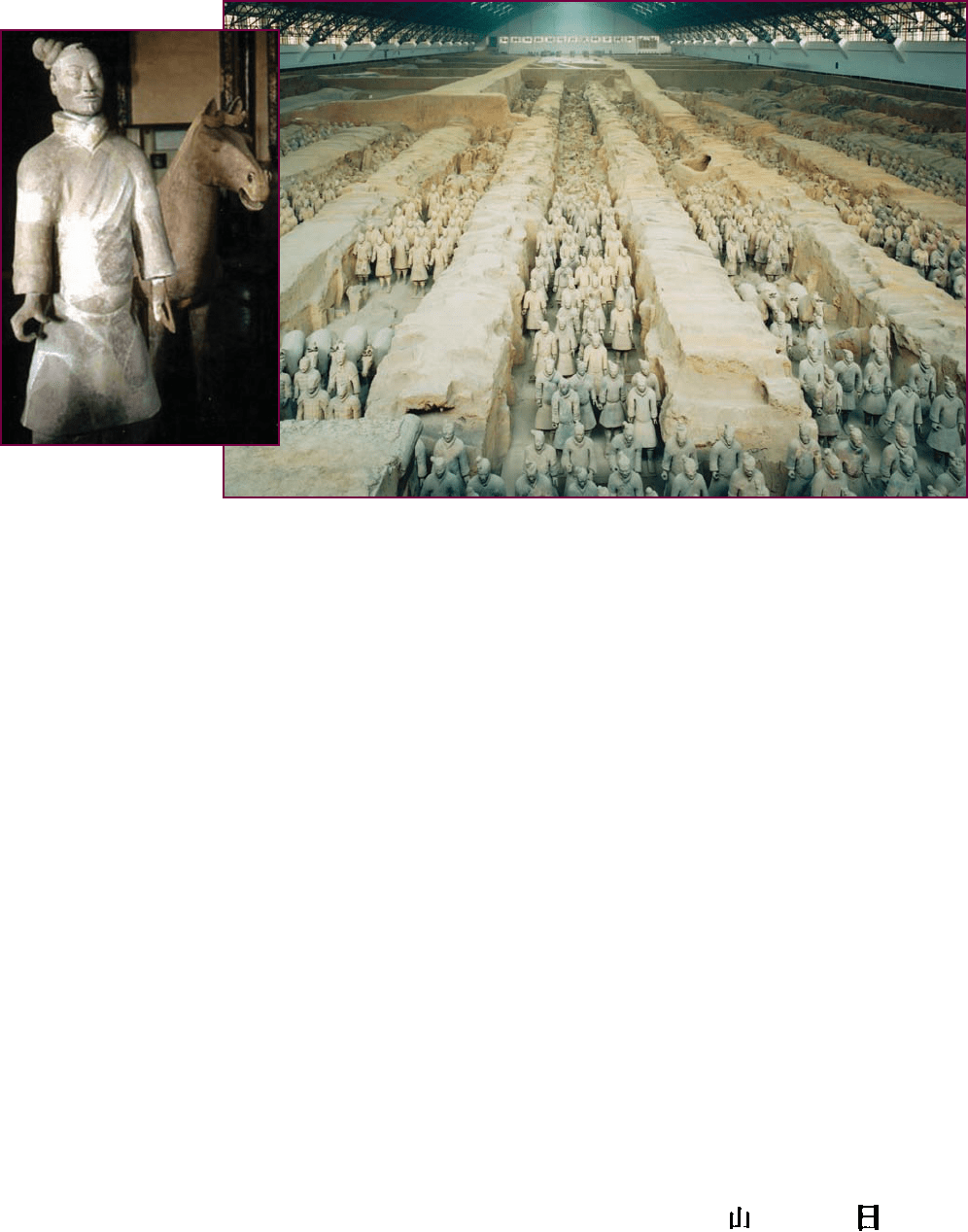

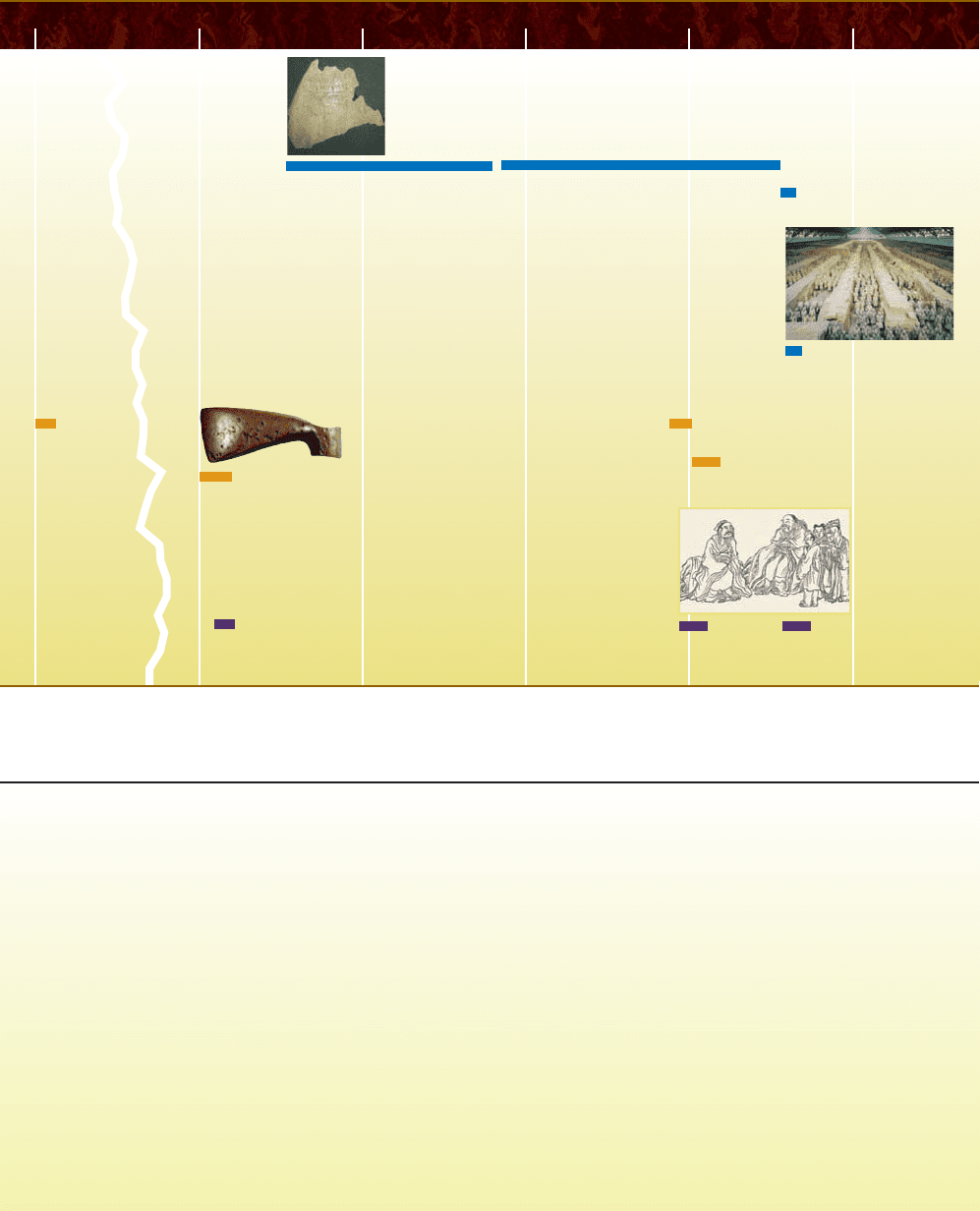

One of the astounding features of the terra-cotta

army is its size. The army is enclosed in four pits that

were originally encased in a wooden framework, which

has since disintegrated. More than a thousand figures

have been unearthed in the first pit, along with horses,

wooden chariots, and seven thousand bronze weapons.

Archaeologists estimate that there are more than six

thousand figures in that pit alone.

Equally impressive is the quality of the work. Slightly

larger than life-size, the figures were molded of finely

textured clay and then fired and painted. The detail on

the uniforms is realistic and sophisticated, but the most

striking feature is the individuality of the facial features of

the soldiers. Apparently, ten different head shapes were

used and were then modeled further by hand to reflect

the variety of ethnic groups and personality types in the

army.

The discovery of the terra-cotta army also shows that

the Chinese had come a long way from the human sac-

rifices that had taken place at the death of Shang sover-

eigns more than a thousand years earlier. But the project

must have been ruinously expensive and is additional

evidence of the burden the Qin ruler imposed on his

subjects. One historian has estimated that one-third of

the national income in Qin and Han times may have been

spent on preparations for the ruler’s afterlife. The em-

peror’s mausoleum has not yet been unearthed, but it is

enclosed in a mound nearly 250 feet high and is sur-

rounded by a rectangular wall nearly 4 miles around.

According to the Han historian Sima Qian, the ceiling is a

replica of the heavens, while the floor contains a relief

model of the entire Qin kingdom, with rivers flowing in

mercury. According to tradition, traps were set within the

mausoleum to prevent intruders, and the workers ap-

plying the final touches were buried alive in the tomb

with its secrets.

Language and Literature

Precisely when writing developed in China cannot be

determined, but certainly by Shang times, as the oracle

bones demonstrate, the Chinese had developed a simple

but functional script. Like many other languages of

antiquity, it was primarily ideographic and pictographic

in form. Symbols, usually called ‘‘characters,’’ were

created to repre sent an ide a or to form a picture of

th e object to be represented. For example, the Chinese

characters for mountain (

), the sun ( ), and the

Qin Shi Huangdi’s Tomb. The First Emperor of Qin ordered the construction of an elaborate

mausoleum, an underground palace complex protected by an army of terra-cotta soldiers and

horses to accompany him on his journey to the afterlife. This massive formation of six

thousand life-size armed soldiers, discovered accidentally by farmers in 1974, reflects Qin Shi

Huangdi’s grandeur and power.

c

William J. Duiker

c

Martin Puddy/Getty Images

74 CHAPTER 3 CHINA IN ANTIQUITY

mo on ( ) w ere meant to represent the objects them-

selves. Other characters, such as ‘‘big’’ (

)(aman

with his arms outstretched), represent an idea. The

character ‘‘east’’ (

)symbolizesthesuncomingup

behind the trees.

Each character, of course, would be given a sound by

the speaker when pronounced. In other cultures, this

process led to the abandonment of the system of ideo-

graphs and the adoption of a written language based on

phonetic symbols. The Chinese language, however, has

never entirely abandoned its original ideographic format,

although the phonetic element has developed into a sig-

nificant part of the individual character. In that sense, the

Chinese written language is virtually unique in the world

today.

One reason the language retained its ideographic

quality may have been the aesthetics of the written

characters. By the time of the Han dynasty, if not earlier,

the written language came to be seen as an art form as

well as a means of communication, and calligraphy

became one of the most prized forms of painting in

China.

Even more import ant, if the written language had

developed in the direction of a phonetic alphabet, it

could no longer have served as the written system for all

the peoples of an expanding civilization. Although the

vast majority spoke a tongue derived from a parent Si-

nitic language (a system distinguished by its variations

in pitch, a characteristic that gives Chinese its lilting

quali ty even today), the languages spoken in various

regions of the country differed from each other in

pronunciation and to a lesser degree in vocabulary and

syntax; for the most part, they were (and are today)

mutually unintelligible.

The Chinese answer to this problem was to give all

the spoken languages the same writing system. Although

any character might be pronounced differently in differ-

ent regions of China, that character would be written the

same way (after the standardization undertaken under the

Qin) no matter where it was written. This system of

written characters could be read by educated Chinese

from one end of the country to the other. It became

the language of the bureaucracy and the vehicle for

the transmission of Chinese culture to all Chinese

from the Great Wall to the southern border and even

beyond. The written language, however, was not identical

with the spoken. Written Chinese evolved a totally sepa-

rate vocabulary and grammatical structure from the

spoken tongues. As a result, those who used it required

special training.

The earliest extant form of Chinese literature dates

from the Zhou dynasty. It was written on silk or strips of

bamboo and consisted primarily of historical records

such as the Rites of Zhou, philosophical treatises such as

the Analects and The Way of the Tao, and poetry, as re-

corded in the Book of Songs and the Song of the South.

In later years, when Confucian principles had been

elevated to a state ideology, the key works identified with

the Confucian school were integrated into a set of so-

called Confucian Classics. These works became required

reading for generations of Chinese schoolchildren and

introduced them to the forms of behavior that would be

required of them as adults.

Music

From early times in China, music was viewed not just

as an aesthetic pleasure but also as a means of achiev ing

political order and refining the human character. In

fact, music may have originated as an accompaniment

to sacred rituals at the royal court. According to the

Historical Records, a history written during the Han

dynasty : ‘‘When our sage-kings of the past instituted

rites and music, their objective was far from making

people indulge in the ... amusements of singing

and dancing. ... Music is produced to purify the hear t,

and rites introduced to rectify the behavior.’’

16

Eventually, however, music began to be appreciated for

its own sake as well as to accompany singing and

dancing.

A wide variety of musical instruments were used,

including flutes, various stringed instruments, bells and

chimes, drums, and gourds. Bells cast in bronze were first

used as musical instruments in the Shang period; they

were hung in rows and struck with a wooden mallet. The

finest were produced during the mid-Zhou era and are

considered among the best examples of early bronze work

in China.

By the late Zhou era, bells had begun to give way as

the instrument of choice to strings and wind instruments,

and the purpose of music shifted from ceremony to en-

tertainment. This led conservative critics to rail against

the onset of an age of debauchery.

Ancient historians stressed the relationship between

music and court life, but it is highly probable that music,

singing, and dancing were equally popular among the

common people. The Book of History, purporting to de-

scribe conditions in the late third millennium

B.C.E.,

suggests that ballads emanating from the popular culture

were welcomed at court. Nevertheless, court music and

popular music differed in several respects. Among other

things, popular music was more likely to be motivated by

the desire for pleasure than for the purpose of law and

order and moral uplift. Those differences continued to be

reflected in the evolution of music in China down to

modern times.

CHINESE CULTURE 75

TIMELINE

5000 B.C.E.

2000 B.C.E. 1500 B.C.E. 1000 B.C.E. 500 B.C.E. 100 B.C.E.

Shang dynasty

First settled

agriculture

Invention of writing system

Life of

Confucius

Qin Shi Huangdi’s tomb

“Hundred schools” of

ancient philosophy

Bronze Age begins

Invention of the iron plow

Origins of Silk Road

Zhou dynasty

Qin dynasty

CONCLUSION

OF THE GREAT CLASSICAL CIVILIZATIONS discussed in

Part I of this book, China was the last to come into full flower. By the

time the Shang began to emerge as an organized state, the societies

in Mesopotamia and the Nile valley had already reached an advanced

level of civilization. Unfortunately, not enough is known about the

early stages of these civilizations to allow us to determine why some

developed earlier than others, but one likely reason for China’s late

arrival was that it was virtually isolated from other emerging centers

of culture elsewhere in the world and thus was compelled to develop

essentially on its own. Only at the end of the first millennium

B.C.E.

did China come into regular contact with other civilizations in South

Asia, the Middle East, and the Mediterranean.

Once embarked on its own path toward the creation of a

complex society, however, China achieved results that were in all

respects the equal of its counterparts elsewhere. By the rise of the

first unified empire in the late third century

B.C.E., the state

extended from the edge of the Gobi Desert in the north to the

subtropical regions near the borders of modern Vietnam in the

south. Chinese philosophers had engaged in debate over intricate

questions relating to human nature and the state of the universe,

and China’s artistic and technological achievements---especially in

terms of bronze casting and the terra-cotta figures entombed in Qin

Shi Huangdi’s mausoleum---were unsurpassed throughout the

world.

In its single-minded effort to bring about the total regimen-

tation of Chinese society, however, the Qin dynasty left a mixed

legacy for later generations. Some observers, notably the China

scholar Karl Wittfogel, have speculated that the need to establish

and regulate a vast public irrigation network, as had been created in

China under the Zhou dynasty, led naturally to the emergence of a

form of Oriental despotism that would henceforth be applied in all

such hydraulic societies. Recent evidence, however, disputes this

view, suggesting that the emergence of a strong central government

followed, rather than preceded, the establishment of a large

76 CHAPTER 3 CHINA IN ANTIQUITY

SUGGESTED READING

The Dawn of Chinese Civilization Several general histories

of China provide a useful overview of the period of antiquity.

Perhaps the best known is the classic East Asia: Tradition and

Transformation (Boston, 1973), by J. K. Fairbank, E. O.

Reischauer, and A. M. Craig. For an authoritative overview of

the ancient period, see M. Loewe and E. L. Shaughnessy, The

Cambridge History of Ancient China from the Origins of

Civilization to 221

B.C. (Cambridge, 1999). Political and social

maps of China can be found in A. Herr mann, A Historical Atlas

of China (Chicago, 1966).

The period of the Neolithic era and the Shang dynasty has

received increasing attention in recent years. For an impressively

documented and annotated overview, see K. C. Chang et al., The

Formation of Chinese Civilization: An Archaeological Perspective

(New Haven, Conn., 2005), and R. Thorp, China in the Early

Bronze Age (Philadelphia, 2005). D. Keightley, The Or igins of

Chinese Civilization (Berkeley, Calif., 1983), presents a number of

interesting articles on selected aspects of the period.

The Zhou and Qin Dynasties The Zhou and Qin dynasties

have also received considerable attention. The former is exhaustively

analyzed in Cho yun Hsu and J. M. Linduff, Westernc Zhou

Civilization (New Haven, Conn., 1988), and Li Xueqin, Eastern

Zhou and Qin Civilizations (New Haven, Conn., 1985). The latter

is a translation of an original work by a mainland Chinese scholar

and is especially interesting for its treatment of the development of

the silk industry and the money economy in ancient China. On

bronze casting, see E. L. Shaughnessy, Sources of Eastern Zhou

History (Berkeley, Calif., 1991). For recent treatments of the

tumultuous Qin dynasty, see M. Lewis, The Early Chinese Empires:

Qin and Han (Cambridge, Mass., 2007), and C. Holcombe, The

Genesis of East Asia, 221

B.C.--A.D. 907 (Honolulu, 2001).

The philosophy of ancient China has attracted considerable

attention from Western scholars. For excerpts from all the major

works of the ‘‘hundred schools,’’ consult W. T. de Bary and

I. Bloom, eds., Sources of Chinese Tradition, vol. 1 (New York,

1999). On Confucius, see B. W. Van Norden, ed., Confucius and

the Analects: New Essays (Oxford, 2002). Also see F. Mote,

Intellectual Foundations of China, 2nd ed. (New York, 1989).

Daily Life in Ancient China For works on general culture

and science, consult the illustrated work by R. Temple, The Genius

of China: 3000 Years of Science, Discovery, and Invention (New

York, 1986), and J. Needham, Science in Traditional China: A

Comparative Perspective (Boston, 1981). See also E. N. Anderson,

The Food of China (New Haven, Conn., 1988). Environmental

issues are explored in M. Elvin, The Retreat of the Elephants: An

Environmental History of China (New Haven, Conn., 2004).

Chinese Culture For an introduction to classical Chinese

literature, consult the three standard anthologies: Liu Wu-Chi, An

Introduction to Chinese Literature (New York, 1961); V. H. Mair,

ed., The Columbia Anthology of Traditional Chinese Literature

(New York, 1994); and S. Owen, ed., An Anthology of Chinese

Literature: Beginnings to 1911 (New York, 1996). For a

comprehensive introduction to Chinese art, consult M. Sullivan,

The Arts of China, 4th ed. (Berkeley, Calif., 1999), with good

illustrations in color. Also see M. Tregear, Chinese Art, rev. ed.

(London, 1997), and Art Treasures in China (New York, 1994).

Also of interest is P. B. Ebrey, The Cambridge Illustrated History of

China (Cambridge, 1999). On some recent finds, consult J. Rowson,

Mysteries of Ancient China: New Discoveries from the Early

Dynasties (New York, 1996). On Chinese music, see J. F. So, ed.,

Music in the Age of Confucius (Washington, D.C., 2000).

irrigation system. The preference for autocratic rule is probably

better explained by the desire to limit the emergence of powerful

regional landed interests and maintain control over a vast empire.

One reason for China’s striking success was undoubtedly that

unlike its contemporary civilizations, it long was able to fend off the

danger from nomadic peoples along its northern frontier. By the

end of the second century

B.C.E., however, the Xiongnu were

looming ominously, and tribal warriors began to nip at the borders

of the empire. While the dynasty was strong, the problem was

manageable, but when internal difficulties began to corrode the

unity of the state, China became increasingly vulnerable to the

threat from the north and entered its own time of troubles.

Meanwhile, another great civilization was beginning to take

form on the northern shores of the Mediterranean Sea. Unlike

China and the other ancient societies discussed thus far, this new

civilization in Europe was based as much on trade as on agriculture.

Yet the political and cultural achievements of ancient Greece were

the equal of any of the great human experiments that had preceded

it and soon began to exert a significant impact on the rest of the

ancient world.

Visit the website for The Essential World History to access study

aids such as Flashcards, Cr itical Thinking Exercises, and

Chapter Quizzes:

www.cengage.com/history/duikspiel/essentialworld6e

CONCLUSION 77

78

CHAPTER 4

THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

CHAPTER OUTLINE

AND FOCUS QUESTIONS

Early Greece

Q

How did the geography of Greece affect Greek history?

Who was Homer, and why was his work used as the

basis for Greek education?

The Greek City-States (c. 750--c. 500 B.C.E.)

Q

What were the chief features of the polis, or city-state,

and how did the city-states of Athens and Sparta differ?

The High Point of Greek Civilization:

Classical Greece

Q

What did the Greeks mean by democracy, and in what

ways was the Athenian political system a democracy?

What effect did the two great conflicts of the fifth

century---the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian

War---have on Greek civilization?

The Rise of Macedonia and the Conquests

of Alexander

Q

How was Alexander the Great able to amass his empire,

and what was his legacy?

The World of the Hellenistic Kingdoms

Q

How did the political and social institutions of the

Hellenistic world differ from those of Classical Greece?

CRITICAL THINKING

Q

In what ways did the culture of the Hellenistic period

differ from that of the Classical period, and what do

those differences suggest about society in the two

periods?

A statue of Pericles in Athens

DURING THE ERA of civil war in China known as the Period of

the Warring States, a civil war also erupted on the northern shores

of the Mediterranean Sea. In 431

B.C.E., two very different Greek

city-states---Athens and Spar ta---fought for domination of the Greek

world. The people of Athens felt secure behind their walls and in

the first winter of the war held a public funeral to hono r those who

had died in battle. On the day of the ceremony, the cit izens of

Athens joined in a procession, with the relatives of the dead wailing

for their loved ones . As was the custom in Athens, one leading citi-

zen was asked to ad dress the crowd, and on this day it was Pericles

who spoke to the peo ple. He talked about the greatness o f Athens

and reminded the Athenians of the strength of their political system:

‘‘Our constitution,’’ he said, ‘‘is called a democracy because power is

in the hands not of a minority but of the whole people. When it is

a question of settling private disputes, everyone is equal before the

law. Just as our political life is free and open, so is our day-to-day

life in our relations with each other. ... Here each individual is

interested not only in his own affairs but in the affairs of the state

as well.’’

In this famous funeral oration, Pericles gave voice to the ideal

of democracy and the importance of the individual, ideals that were

79

c

British Museum, London, UK/The Bridgeman Art Library

Early Greece

Q

Focus Questions: How did the geography of Greece

affect Greek history? Who was Homer, and why was

his work used as the basis for Greek education?

Geography played an important role in Greek history.

Compared to Mesopotamia and Egypt, Greece occupied a

small area, a mountainous peninsula that encompassed

only 45,000 square miles of territory, about the size of the

state of Louisiana. The mountains and the sea were es-

pecially significant. Much of Greece consists of small

plains and river valleys surrounded by mountain ranges

8,000 to 10,000 feet high. The mountains isolated Greeks

from one another, causing Greek communities to follow

their own separate paths and develop their own ways of

life. Over a period of time, these communities became so

fiercely attached to their independence that they were

only too willing to fight one another to gain advantage.

No doubt the small size of these independent Greek

communities fostered participation in political affairs and

unique cultural expressions, but the rivalry among them

also led to the internecine warfare that ultimately devas-

tated Greek society.

The sea also influenced Greek societ y. Greece had a

long seacoast, dotted by bays and inlets that provided

numerous harbors. The Greeks also inhabited a

number of islands to the west, south, and par ticularly

the east of the Greek mainland. It is no accident that

the Greeks became seafarers who sailed out into the

Aegean and Mediterranean seas to make contact

with the outside world and later to establish colonies

that would spread Greek civ ilization throughout t he

Mediterranean.

Greek topography helped determine the major ter-

ritories into which Greece was ultimately divided (see

Map 4.1). South of the Gulf of Corinth was the Pelo-

ponnesus, vir tually an island connected to the main-

land by a narrow isthmus. Consisting mostly of hills,

mountains, and small valleys, the Peloponnesus was

home to the city-state of Sparta. Northeast of the Pelo-

ponnesus was the Attic peninsula (or Attica), the site of

Athens, hemmed in by mountains to the north and west

and surrounded by the sea to the south and east.

Northwest of Attica was Boeotia in central Greece, with its

chief city of Thebes. To the north of Boeotia was Thessaly,

which contained the largest plains and became a great

producer of grain and horses. To the north of Thessaly lay

Macedonia, which was of minor importance in Greek

history until 338

B.C.E., when the Macedonian king con-

quered the Greeks.

Minoan Crete

The earliest civilization in the Aegean region emerged on

the large island of Crete, southeast of the Greek mainland.

A Bronze Age civilization that used metals, especially

bronze, in making weapons had been established there by

2800

B.C.E. This civilization was discovered at the turn of

the twentieth century by the English archaeologist Arthur

Evans, who named it ‘‘Minoan’’ after Minos, a legendary

king of Crete. In language and religion, the Minoans were

not Greek, although they did have some influence on the

peoples of the Greek mainland.

Evans’s excavations on Crete at the beginning of

the twentieth century unear thed an enormous palace

complex at Knossus, near modern Heracleion. The re-

mains revealed a prospe rous culture with Kn ossus as

the apparent center of a far-ranging ‘‘sea empire’’ based

on trade.

The Minoan civ ilization reached its height between

2000 and 1450

B.C.E. The palace at Knossus, the royal

seat of the kings, was an elaborate structure that in-

cluded numerous private living rooms for the royal

family and workshops for making decorated vases, ivory

fi gurin es, and j ewelry. Even bathrooms, w ith elaborate

80 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

quite different from those of some other ancient societies, in which

the individual was subordinated to a larger order based on obedi-

ence to an exalted ruler. The Greeks asked some basic questions

about human life: What is the nature of the universe? What is the

purpose of human existence? What is our relationship to divine

forces? What constitutes a community? What constitutes a state?

What is truth, and how do we realize it? Not only did the Greeks

answer these questions, but they also derived a system of logical,

analytical thought to examine them. Their answers and their system

of rational thought laid the intellectual foundation of Western

civilization’s understanding of the human condition.

The remarkable story of ancient Greek civ ilization begins w ith

the arrival of the Greeks around 1900

B.C.E. By the eighth century

B.C.E., the characteristic institution of ancient Greek life, the polis, or

city-state, had emerged. Greek civilization flourished and reached its

height in the Classical era of the fifth century

B.C.E., but the inability

of the Greek states to end their fratricidal warfare eventually left

them vulnerable to the Macedonian king Philip II and helped bring

an end to the era of independent Greek city-states.

Although the city-states were never the same after their defeat

by the Macedonian monarch, this defeat did not bring an end to

the influence of the Greeks. Philip’s son Alexander led the Macedo-

nians and Greeks on a spectacular conquest of the Persian Empire

and opened the door to the spread of Greek culture throughout

the Middle East.

drains, like those found at Mohenjo-Daro in India,

formed par t of the complex. The rooms were decorated

with brightly colored frescoes showing sporting events

and nature scenes.

The centers of Minoan civilization on Crete suffered a

sudden and catastrophic collapse ar ound 1450

B.C.E.Some

historians believe that a tsunami triggered by a powerful

volcanic eruption on the island of Thera was responsible

for the devastation, but most historians maintain that the

destruction was the result of invasion and pillage by

mainland Greeks known as the Mycenaeans.

The First Greek State: Mycenae

The term Mycenaean is derived from Mycenae, a fortified

site excavated by an amateur German archaeologist,

Heinrich Schliemann, starting in 1870. Mycenae was one

center in a civilization that flourished between 1600 and

1100

B.C.E. The Mycenaean Greeks were part of the Indo-

European family of peoples (see Chapter 1) who spread

from their original location into southern and western

Europe, India, and Persia. One group entered the terri-

tory of Greece from the north around 1900

B.C.E. and

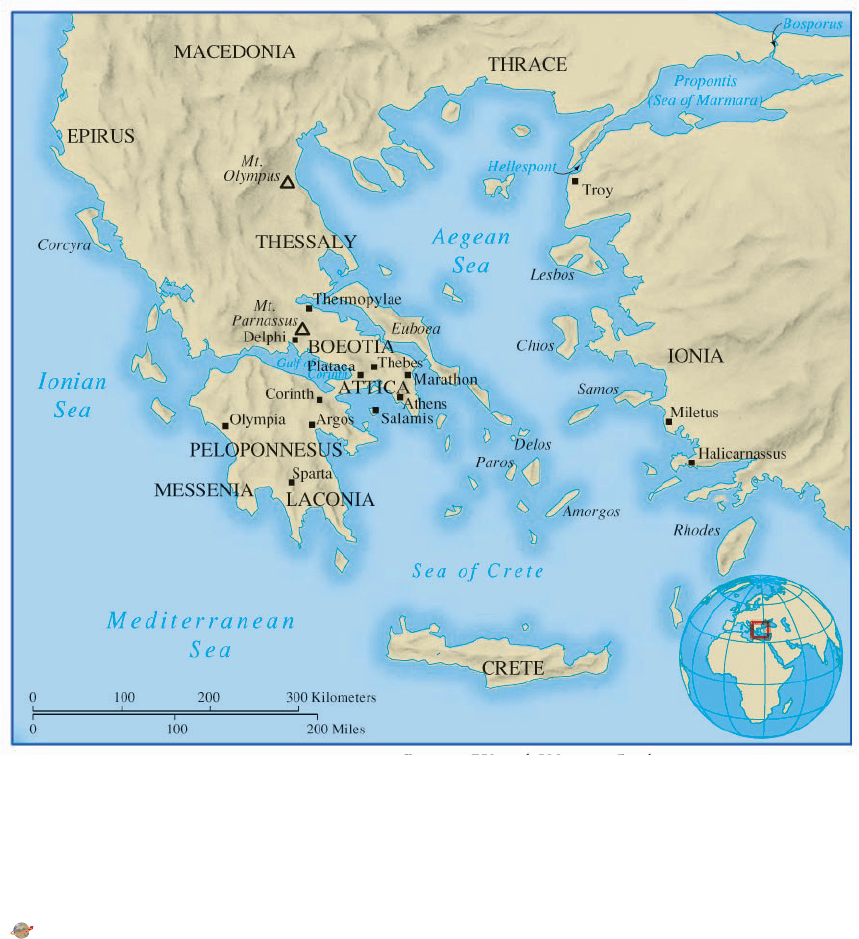

MAP 4.1 Ancient Greece (c. 750–338 B.C.E.). Between 750 and 500 B.C.E., Greek

civilization witnessed the emergence of the city-state as the central institution in Greek life

and the Greeks’ colonization of the Mediterranean and Black seas. Classical Greece lasted from

about 500 to 338

B.C.E. and encompassed the high points of Greek civilization in the arts,

science, philosophy, and politics, as well as the Persian Wars and the Peloponnesian War.

Q

HowdoesthegeographyofGreecehelpexplaintheriseanddevelopmentoftheGreek

city-state?

View an animated version of this map or related maps at www .c engage.com/history/

duikspiel/essentialworld6e

EARLY GREECE 81

eventually managed to gain control of the Greek main-

land and develop a civilization.

Mycenaean civilization, which reached its high point

between 1400 and 1200

B.C.E., consisted of a number of

powerful monarchies that

resided in fortified palace

complexes. Like Mycenae,

they were built on hills

and surrounded by gi-

gantic stone walls. These

various centers of power

probably formed a loose

confederacy of indepen-

dent states, with Mycenae

being the strongest. The

Mycenaeans were war-

riors who prided them-

selves on their heroic

deeds in battle. Some scholars believe that the Myce-

naeans spread outward and conquered Crete. The most

famous of their supposed military adventures has come

down to us in the epic poetry of Homer (see ‘‘Homer’’

later in this chapter). Did the Mycenaean Greeks, led by

Agamemnon, king of Mycenae, sack the city of Troy on

the northwestern coast of Asia Minor around 1250

B.C.E.?

Ever since Schliemann began his excavations in 1870,

scholars have debated this question. Many believe that

Homer’s account does have a basis in fact, even if the

details have become shrouded in mystery.

By the late thirteenth century

B.C.E., Mycenaean

Greece was showing signs of serious trouble. Mycenae

itself was torched around 1190

B.C.E., and other Myce-

naean centers show similar patterns of destruction as new

waves of Greek-speaking invaders moved into Greece

from the north. By 1100, Mycenaean culture was coming

to an end, and the Greek world was entering a new period

of considerable insecurity.

The Greeks in a Dark Age (c. 1100--c. 750 B.C.E.)

After the collapse of Mycenaean civilization, Greece en-

tered a difficult era of declining population and falling

food production; not until 850

B.C.E. did farming---and

Greece itself---revive. Because of both the difficult con-

ditions and the fact that we have few records to help us

reconstruct what happened in this period, historians refer

to it as the Dark Age.

During the Dark Age, large numbers of Greeks left

the mainland and migrated across the Aegean Sea to

various islands and especially to the southwestern shore

of Asia Minor, a strip of territory that came to be called

Ionia. Two other major groups of Greeks settled in es-

tablished parts of Greece. The Aeolians from northern

and central Greece colonized the large island of Lesbos

and the adjacent mainland. The Dorians established

themselves in southwestern Greece, especially in the Pel-

oponnesus, as well as on some south Aegean islands,

including Crete.

As trade and economic activity began to recover, iron

replaced bronze in the construction of weapons, making

them affordable for more people. At some point in the

eighth century

B.C.E., the Greeks adopted the Phoenician

alphabet to give themselves a new system of writing. Near

the very end of the Dark Age appeared the work of Ho-

mer, who has come to be viewed as one of the great poets

of all time.

Homer The first great epics of early Greece, the Iliad

and the Odyssey, were based on stories that had been

passed down from generation to generation. It is gener-

ally assumed that early in the eighth century

B.C.E., Homer

made use of these oral traditions to compose the Iliad, his

epic poem of the Trojan War. The war began after Paris, a

prince of Troy, kidnapped Helen, wife of the king of the

Greek state of Sparta. All the Greeks were outraged, and

led by the Spartan king’s brother, Agamemnon of Myce-

nae, they attacked Troy. After ten years of combat, the

Greeks finally sacked the city. The Iliad is not so much

the story of the war itself, however, as it is the tale of the

Greek hero Achilles and how the ‘‘wrath of Achilles’’ led

to disaster. The Odyssey, Homer’s other masterpiece, is an

epic romance that recounts the journeys of another Greek

hero, Odysseus, after the fall of Troy and his eventual

return to his wife, Penelope, after twenty years.

The Greeks regarded the Iliad and the Odyssey as

authentic history as recorded by one poet, Homer. The

epics gave the Greeks an idealized past, a legendary age of

heroes, and the poems became standard texts for the

education of generations of Greek males. As one Athenian

stated, ‘‘My father was anxious to see me develop into a

good man ...and as a means to this end he compelled me

to memorize all of Homer.’’

1

The values Homer incul-

cated were essentially the aristocratic values of courage

and honor (see the box on p. 83). It was important to

strive for the excellence befitting a hero, which the Greeks

called arete. In the warrior-aristocratic world of Homer,

arete is won in struggle or contest. Through his willing-

ness to fight, the hero protects his family and friends,

preserves his own honor and his family’s, and earns his

reputation. In the Homeric world, aristocratic women,

too, were expected to pursue excellence. For example,

Odysseus’ wife, Penelope, remains faithful to her husband

and displays great courage and intelligence in preserving

their household during her husband’s long absence.

To a later generation of Greeks, these heroic values

formed the core of aristocratic virtue, a fact that explains

M

M

MY

CE

CE

E

E

NANA

N

NA

N

NA

N

NA

NA

NA

NA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

EA

E

A

EA

A

N

N

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

A

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

NA

GR

GR

R

R

EE

E

E

EE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

CE

CE

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

C

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

E

Sea o

f

Cret

e

T

Th

The

The

ra

a

a

Pyl

y

y

os

y

y

y

y

y

y

Orc

Orc

c

c

c

O

c

hom

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

eno

s

s

s

s

s

c

c

c

c

c

c

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

h

eno

s

s

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Ti

Ti

Ti

Tir

y

y

y

yn

yns

ns

y

y

y

y

y

s

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

Tir

y

y

y

y

y

y

y

Kno

Kno

Kno

Kno

Kno

Kn

o

Kno

K

Kno

Kno

o

o

ss

ss

s

ssu

ssu

ssu

ssu

u

ssu

s

ss

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

s

Kno

Kno

Kno

K

Kno

K

Kno

no

no

ss

ss

ss

ssu

ssu

ssu

s

s

s

s

s

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

M

Myc

Myc

Myc

Myc

M

ena

n

na

na

ena

na

ena

na

ena

ena

ena

ena

a

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

c

c

e

e

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

M

na

na

na

na

na

na

na

na

n

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

e

0

50

1

00

Mile

s

0 50 100 150

Ki

Kil

il

omet

omet

o

ers

ers

ers

ers

s

ers

ers

ers

Minoan Crete and

Mycenaean Greece

82 CHAPTER 4 THE CIVILIZATION OF THE GREEKS

the tremendous popularity of Homer as an educational

tool. Homer gave the Greeks a universally accepted model

of heroism, honor, and nobility. But in time, as city-states

proliferated in Greece, new values of cooperation and

community also transformed what the Greeks learned

from Homer.

The Greek City-States

(c. 750--c. 500

B.C.E.)

Q

Focus Question: What were the chief features of the

polis, or city-state, and how did the city-states of

Athens and Sparta differ?

During the Dark Age, Greek villages gradually expanded

and evolved into independent city-states. In the eighth

century

B.C.E., Greek civilization burst forth with new

energies, beginning the period that historians have called

the Archaic Age of Greece. Two major developments

stand out in this era: the evolution of the city-state, or

what the Greeks called a polis (plural, poleis), as the

central institution in Greek life and the Greeks’ coloni-

zation of the Mediterranean and Black seas.

The Polis

In the most basic sense, a polis could be defined as a small

but autonomous political unit in which all major politi-

cal, social, and religious activities were carried out at one

central location. The polis consisted of a city, town, or

village and its surrounding countryside. The city, town, or

village was the focus, a central point where the citizens of

the polis could assemble for political, social, and religious

activities. In some poleis, this central meeting point was a

hill, like the Acropolis at Athens, which could serve as a

HOMER’S IDEAL OF EXCELLENCE

The Iliad and the Odyssey, which the Greeks

believed were both written by Homer, were used

as basic texts for the education of Greeks for

hundreds of years during antiquity. This passage

from the Iliad, describing the encounter between Hector, prince

of Troy, and his wife, Andromache, illustrates the Greek ideal of

gaining honor through combat. At the end of the passage,

Homer also reveals what became the Greek attitude toward

women: they are supposed to spin and weave and take care

of their households and children.

Homer, Iliad

Hector looked at his son and smiled, but said nothing. Andromache,

bursting into tears, went up to him and put her hand in his.

‘‘Hector,’’ she said, ‘‘you are possessed. This bravery of yours will

be your end. You do not think of your little boy or your unhappy

wife, whom you will make a widow soon. Some day the Achaeans

[Greeks] are bound to kill you in a massed attack. And when I lose

you I might as well be dead. ... I have no father, no mother,

now. ... I had seven brothers too at home. In one day all of them

went down to Hades’ House. The great Achilles of the swift feet

killed them all. ...

‘‘So you, Hector, are father and mother and brother to me, as

well as my beloved husband. Have pity on me now; stay here on the

tower; and do not make your boy an orphan and your wife a

widow. ...’’

‘‘All that, my dear,’’ said the great Hector of the glittering hel-

met, ‘‘is surely my concern. But if I hid myself like a coward and re-

fused to fight, I could never face the Trojans and the Trojan ladies

in their trailing gowns. Besides, it would go against the grain, for I

have trained myself always, like a good soldier, to take my place in

the front line and win glory for my father and myself. ...’’

As he finished, glorious Hector held out his arms to take his

boy. But the child shrank back with a cry to the bosom of his gir-

dled nurse, alarmed by his father’s appearance. He was frightened by

the bronze of the helmet and the horsehair plume that he saw nod-

ding grimly down at him. His father and his lady mother had to

laugh. But noble Hector quickly took his helmet off and put the

dazzling thing on the ground. Then he kissed his son, dandled him

in his arms, and prayed to Zeus and the other gods: ‘‘Zeus, and you

other gods, grant that this boy of mine may be, like me, preeminent

in Troy; as strong and brave as I; a mighty king of Ilium. May peo-

ple say, when he comes back from battle, ‘Here is a better man than

his father.’ Let him bring home the bloodstained armor of the

enemy he has killed, and make his mother happy.’’

Hector handed the boy to his wife, who took him to her fra-

grant breast. She was smiling through her tears, and when her hus-

band saw this he was moved. He stroked her with his hand and

said, ‘‘My dear, I beg you not to be too much distressed. No one is

going to send me down to Hades before my proper time. But Fate

is a thing that no man born of woman, coward or hero, can escape.

Go home now, and attend to your own work, the loom and the

spindle, and see that the maidservants get on with theirs. War is

men’s business; and this war is the business of every man in Ilium,

myself above all.’’

Q

What important ideals for Greek men and women does

this passage from the Iliad reveal? How do the women’s ideals

compare with those for ancient Indian and Chinese women?

THE GREEK CITY-STATES (C.750--C.500B.C.E.) 83