Drinkwater J.F. The Alamanni and Rome 213-496 (Caracalla to Clovis)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

conXuence with the Upper Rhine; (c) the middle Neckar; and (d) the

Breisgau. Lesser concentrations are situated along: (e) the Swabian

Alp, north of the Danube; and (f) the High Rhine, between Kaiser-

augst and Lake Constance.42 Settlement was also clearly attracted to

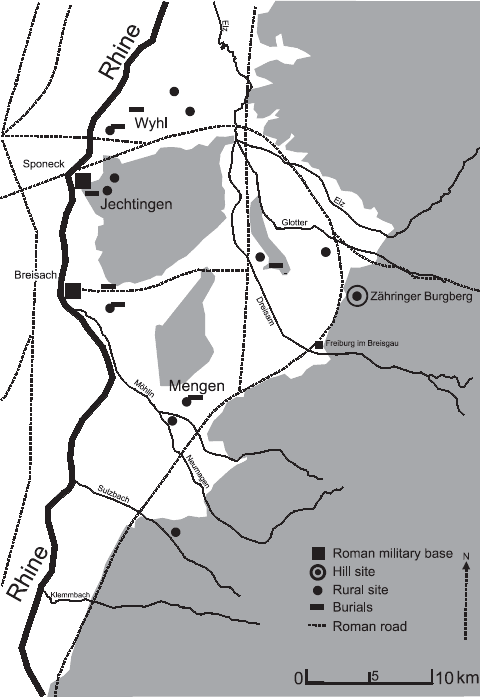

Fig. 9 The Breisgau [from Bu

¨

cker (1999: 15 Fig . 1); ß Jan Thorbecke

Verlag, OstWldern].

42 Schach-Do

¨

rges (1997: Fig. 83). Cf. Roeren (1960: Fig. 2); Ger manen (1986:

345–6 and Fig. 69); Planck (1990: 92); Schmid (1990: 18).

88 Settlement

Roman military installations, which oVered access to imperial manu-

factured goods and service in the imperial army.43 A number of

important sites, for example those at Mengen and the Za

¨

hringer

Burgberg, are found near the imperial frontier44 (Fig. 9). This must

reXect a desire on the part of those who lived there to be neighbours

of the Empire, and a belief that they would not be subjected to

Roman harassment.

This attitude was based on experience. Though Ammianus is

usually interested only in Roman frustration of Alamannic hopes

in this respect, Symmachus shows that the Roman side was not averse

to cooperation.45 Here too, however, there are currently anomalies.

For example, Germanic Wnds over the Rhine from Kaiseraugst,

though signiWcant, do not fully match the Roman or, indeed, reXect

what we know from written sources was a strong Roman interest in

the area.46 Given what was happening opposite Breisach, Giesler’s

explanation for the phenomenon—that the region lay distant from

the main lines of Alamannic expansion and was exposed to the threat

of Roman military intervention—is unconvincing.47

The land that Rome in eVect ceded to local Elbgermanic leaders by

tolerating the settlement of their groups was probably distributed by

them among their followers, according to rank. On this land devel-

oped the rural sites and the ‘Ho

¨

hensiedlungen’.

Alamannic settlement was almost entirely rural. The vast majority

of the population lived in small villages or hamlets, or on isolated

farms. They would have used simple wooden-framed buildings,

some, at ground level, for habitation, others, slightly below (the

typically Germanic ‘Grubenha

¨

user’), for storage and artisanal activ-

ities. The decay of such timber structures would have forced reloca-

tion probably every 30–50 years. They are hard to detect and

excavate. Since very few such sites are known, we have little idea of

43 Cf. below 163; Bu

¨

cker (1999: 217–18). For the similar eVect of Roman bases on

the Danube on Marcomannic settlement in the second century see Burns (2003: 231).

44 Cf. Fig. 8 for the concen tration of Alamannic settlements along the Upper Rhine near

the conXuences of the Main and the Neckar and around Breisach during the fourt h century.

45 e.g. AM 27.10.7 (368); cf. Symmachus, Orat. 2.10 (369), and below 217–18, 290.

Contra Pabst (1989: 331), it would appear that the Alamanni chose to settle near

forts, and not that the forts were built to face concentrations of Alamanni.

46 Cf. below 219.

47 Cf. below 101; Giesler (1997: 209–11).

Settlement 89

the dynamics of their distribution: for example, their relationship to

Roman settlements and roads,48 or the local densities or overall level

of population. However, a population level low in comparison with

that of the Roman period is suggested by other studies. This is

crucial, for it returns us to the enormous disparity in strength

between Alamannic society and the Roman Empire. Aurelius Victor

and Ammianus Marcellinus famously describe the Alamanni as being

many in number.49 There appears to be no basis in fact for such an

assertion. What we have is prejudice: general, in that both authors

pick up the ancient ethnographical tradition that viewed all northern

barbarians as inordinately proliWc; and particular, in that both

wished to maximize Julian’s Alamannic victories.50

The occupants of Alamannic settlements regularly smelted and

forged iron and so had relatively good access to iron tools. Indeed,

it has been claimed that their scythe and plough show signs of

innovation—taking them beyond Roman standards.51 On the other

hand, the ev idence for such improvement suggests a relatively late

date, during the Wfth century,52 and it may be explicable in terms of

developments speciWc to the period.53 The overwhelming impression

is that, during the fourth century, Alamannic agriculture was sig-

niWcantly diVerent from its Roman predecessor.

The Romans cultivated specialized crops (for example, spelt

wheat) on large estates for sale into a distant market. The Alamanni

appear to have grown a w ider range of produce on individual farms

for subsistence. Barley (a summer crop, the cultivation of which

generated useful free time in autumn and winter and would have

allowed fallow pasturage) predominated. In shor t, the Alamanni

practised a typically Germanic (as opposed to Celtic or Roman)

form of agriculture, earlier characterized by Tacitus as being centred

on pastoral farming.54 However, there was some divergence from this

48 Bu

¨

cker et al. (1997); Bu

¨

cker (1999: 208–11); Fingerlin (1990: 112), (1997a–b:

107–8, 125, 127–9, 133).

49 Aurelius Victor, Caesares 21.2: gens populosa; AM 16.12.6: populosae gentes.

50 Below 141–2, 176, 237–8.

51 Henning (1985); Planck (1990: 87–90); Amrein and Binder (1997: 360); Bu

¨

cker

et al. (1997: 318); Bu

¨

cker (1999: 198–201); Fingerlin (1993: 69), (1997a–b: 108, 131–3).

52 Henning (1985: 590).

53 Cf. below 338.

54 Tacitus, Germania 5.2. I am very grateful to Dr A. Kreuz for her comments on

this section, the responsibility for which, of course, remains entirely mine.

90 Settlement

model. Other cereals and plants were grown, including species which

demanded a degree of care, such as protein-rich lentils, and garden

plants (various vegetables and herbs, mustard, cherry, Wg, grape)

brought in by the Romans. The presence of the latter category

suggests some element of continuity in food production between

the two periods.55 Elsewhere we Wnd evidence for a similar pattern of

major discontinuity accompanied by minor continuity.

In the Breisgau, there may have been a move to more pastoral

farming, with the average size of cattle gradually declining to that of

the Germanic norm. On the other hand, smaller animals introduced

under the Romans (for example, duck and goose) continued to be

raised.56 The sense of regression in agricultural activity receives con-

Wrmation from pollen analysis. There was a long period of signiWcant

reforestation in the fourth century, the sign of a smaller population

failing to maintain previously cultivated land.57 One has to be careful

with such evidence. It is not totally generalizable: in some places

reforestation did not occur.58 And the failure to Wnd settlements

does not necessarily mean that these did not exist. As ever, ‘voids’ on

maps may be due to lack of archaeological activity or expertise rather

than to distribution of population. In the Breisgau, recent advances in

archaeology have revealed many more sites than were previously

known, and have indicated a signiWcant growth in the Germanic

population of the area from the early fourth century.59 However, this

is best treated as exceptional, caused by the area’s proximity to Roman

military bases.60 Generally, the size of population that Alamannic

agriculture could support must have fallen well below the Roman

level, a level not reached again until the seventh century.61

55 Ro

¨

sch (1997: 323–4, 326); Bu

¨

cker (1999: 204–5).

56 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 202–4); Kokabi (1997: 331–3, and 334: the relative modesty of

sixth and seventh-century meat oVerings in graves). Kreuz (1999: 82–3), however,

prudently warns against taking big as ‘good’ and little as ‘bad’: much depends on the

needs of society.

57 Ro

¨

sch (1997: 324, 327–9 and Figs 357–8), pollen diagrams from Hornstaad and

Moosrasen, by Lake Constance. For the presence of beech pollen as a general

indicator of reforestation and of the associated return of ‘prehistoric settlement

strategies’ in the late Antique and medieval periods, see Ku

¨

ster (1998: 79).

58 Stobbe (2000: 213): of three sites investigated in the Wetterau, two showed signs

of reforestation, one did not.

59 Fingerlin (1990: 101–3), (1997a: 107, 131).

60 Fingerlin (1990: 110–12), (1993: 67); Bu

¨

cker (1999: 217–18).

61 Ro

¨

sch (1997: 324, 327–9).

Settlement 91

Despite frequent signs of iron-working, early Alamannic rural sites

do not appear to have been great producers of manufactured items,

or commercial centres. Their occupants made basic subsistence-

goods which comprised, along with iron objects, hand-formed (not

wheel-thrown) pottery, textiles, and other everyday items in leather,

bone and horn.62 The exchange of goods between settlements,

though it existed, was small and over short distances: a maximum

of 30 km (c.18 statute miles) has been proposed.63 What is even more

remarkable is that such sites consistently yield very few imported

Roman wares, even at relatively important locations, such as the

fortiWed settlement at Sontheim-im-Stubental, and in places, such

as Mengen, in close proximity to the Empire. This is in stark contrast

to the relatively large amounts of such material and evidence for

highly-skilled artisanal activity found on the hill-sites (discussed

next).64 This is not to disparage Alamannic rural skill entirely.

There are examples of bronze-working away from the hill-sites, for

example at the Wurmlingen villa.65 And though Alamannic hand-

formed pottery resembles the late Iron Age pottery of the region,

which has confused its interpretation, recent investigation has

revealed that it was signiWcantly better produced, perhaps as a result

of the copying of Roman techniques.66 It is also being increasingly

realized that, despite the prevalence of hand-formed pottery, in the

vicinity of rural sites and hill-sites there were local attempts to

produce wheel-thrown vessels, again copying Roman forms.67

There are, indeed, interesting incidences of larger-scale production

of Roman-style Wneware, along with Germanic pottery made by

Roman methods and inXuenced by Roman style, in Free Germany

(at Haarhausen, south of Erfurt, and at Eßleben, north of Wu

¨

rzburg)

in the late third century68 (Fig. 4). Such fairly sophisticated operations

62 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 198–202).

63 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 160).

64 Below 95. Generally: Bu

¨

cker (1997: 139); Hoeper (1998: 330–1, 339–40). Iller–

Danube region: Planck (1990: 94). Breisgau: Fingerlin (1997a: 106–8); Bu

¨

cker (1999:

167–8, 216–17), noting that at Mengen only 6 per cent of the ceramics found were

Roman imports, as against 39 per cent on the Za

¨

hringer Burgberg.

65 Reuter (1997: 67).

66 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 158–9, 216).

67 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 152, 158–9 and nn.436, 452: LauVen; Runder Berg).

68 Teichner (2000).

92 Settlement

(which included the manufacture of food preparation vessels:

mortaria69) can only have been the work of Romans, free or slave.

However, attempts at more sophisticated ceramic production

remained local and marginal; the Haarhausen–Eßleben experiments

appear to have lasted no more than a generation.70 The Alamanni

continued to manufacture and use predominantly hand-made pot-

tery, and the production of high-quality ceramics, and glassware,

remained a Roman speciality. As Matthews remarks, ‘Alamannic

technology was not advanced.’71 It has been suggested that a major

shift in the siting of their farms closer to water sources, which began

around 400, was due, inter alia, to the failure of the Alamanni to

maintain Roman irrigation systems.72 Given the likely weaknesses in

their agriculture, level of population and technology, it is improbable

that they could have borne the sorts of demands that some have

suggested were imposed upon them in the late third century.73

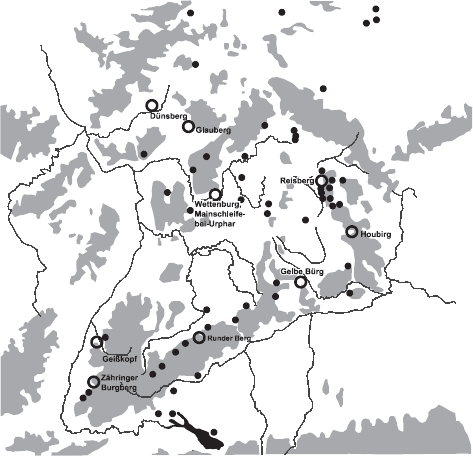

Not all Alamanni, however, lived exclusively on the land. We now

know of small-scale but signiWcant habitation on prominent hill-

tops: the so-called ‘Ho

¨

hensiedlungen’—‘hill-settlements’ or, as I

prefer to call them to avoid implying permanent residence or uni-

form function, ‘hill-sites’74 (Fig. 10). The modern pioneer in the Weld

was Werner. In the early 1960s, he was able to list about a dozen

probable sites; this number has since grown to over 60.75 However,

only a very few have been subjected to close archaeological scrutiny.

By the late 1990s, indeed, just 10 of 62 proposed sites had been

conWrmed as Alamannic ‘Ho

¨

hensiedlungen’.76 Of these, only that of

the Runder Berg, near Urach (1)77 had been fully excavated. Near the

Rhine frontier, signiW cant work has been done on the Za

¨

hringer

69 Schallmayer (1995: 58); cf. above 36.

70 Bu

¨

cker (1997: 135–6, 139–40); Steuer (1998: 290); Steidl (2002: 87–9, 98–111).

Cf. below 140.

71 Matthews (1989: 312).

72 Weidemann (1972: 114–23, 154); Keller (1993: 97–100).

73 Above 82.

74 Cf. Hoeper (1998: 341): ‘Ho

¨

henstationen’.

75 Werner (1965: 81–90 and Fig. 2), citing earlier work by Dannenbauer; Steuer

(1990: Catalogue [45 sites]: 146–68); Fingerlin (1997b); Steuer (1997a: esp. 149 and

Fig. 145); Hoeper (1998: Catalogue [62 sites]: 344–5); Haberstroh (2000a: 47–52).

76 Hoeper (1998: 325).

77 Numeration from Steuer (1990), Hoeper (1998).

Settlement 93

Burgberg, near Freiburg (2), and on the Geißkopf near OVenburg

(49); and, in the Alamannic hinterland, at Du

¨

nsberg, near Gießen

(4), Glauberg, in the Wetterau (5), on the Wettenburg, Mainschleife-

bei-Urphar (3), at Reisberg, near Scheßlitz (12), Houbirg in

Franconia (7), and Gelbe Bu

¨

rg, near Dittenheim (6).78 It is certain

that more hill-sites will be found, and that excavation of the ones we

know will expand understanding of their form, distribution, dating

and function. In addition, it may be that in non-hilly areas other sites

will be recognized as having served a similar purpose.79 For the

moment, analysis will have to proceed based on the little we know.

Some hill-sites were constructed anew; others were built over Iron

Age hill-forts. They were occasionally walled, as at Glauberg and

StaVelberg (near StaVelstein) (10), but heavy defences are not one of

their chief characteristics.80 They vary greatly in area, from c.0.5

Rhine

Rhine

Moselle

Main

Main

Danube

L. Constance

Rhine

LahnLahn

NeckarNeckar

Staffelberg

Regnitz

Fig. 10 Known hill-sites, exca vated sites named [after Hoeper (1998: 327 Fig. 1b)].

78 Steuer (1990); Fingerlin (1997b: 127); Steuer (1997a: 154–7); Hoeper (1998:

329). See also Haberstroh (2000a: 48–9).

79 Below 98.

80 Steuer (1990: 169, 172); Haberstroh (2000a: 47, 49–50).

94 Settlement

to over 10 ha (1.5–25 acres), though the largest were never fully

occupied.81 Common to all, despite their diVerences, and, as we

have seen, sharply distinguishing them from rural settlements, are

signs of material prosperit y and specialized military and artisanal

activity. Finds include weaponry, ornaments of male and female

dress (for example, Roman-style military belt-Wttings, brooches),

Roman ceramics and g lassware, and evidence of local craftwork

(often using Roman scrap).82 Alamannic technology was unsophis-

ticated and the only sources of such items were the Roman Empire or

craftsmen trained in Roman techniques. Though clearly esteemed by

the Alamanni, these goods are unevenly distributed from hill-site to

hill-site, and not particularly remarkable in the context of the full

repertoire of Roman manufactures.83 The lifestyle of those who used

them was rich by local but mediocre by imperial standards. Hill-sites

began to be built in the late third and early fourth centuries and

continued in use until the Frankish takeover, early in the sixth.84

They experienced various shifts in fortune. The Runder Berg, for

example, began life in the early fourth century, was destroyed around

400, but recovered and was Wnally abandoned in panic around 500.85

The Za

¨

hringer Burgberg was settled in the early fourth century,

remodelled in the course of that century and occupied until the

mid-Wfth century. 86 Glauberg was built on a prehistoric site around

300, and persisted until c.500.87

Explanation of the hill-sites has ranged from refuges and guard-

posts to army-camps and cult-centres.88 A widely held view is that

the largest ‘Ho

¨

hensiedlungen’ were the seats of power of local leaders:

‘Herrschaftszentren’. They contained the residences of chiefs and

81 Steuer (1990: 68–9).

82 Fingerlin (1997b: 126–7); Steuer (1990: 170, 195), (1997: 157); Hoeper (1998:

330–2).

83 Bu

¨

cker (1999: 152), (1997: 136), concerning glassware but, I believe, with equal

relevance to ceramics etc.); cf. Hoeper (1998: 330).

84 Steuer (1997a: 153–4).

85 Steuer (1990: 147); cf. Fingerlin (1990: 106), (1993: 65); Koch (1997a: 192);

Hoeper (1998: 329).

86 Steuer (1990: 148–9), (1997: 154–7); Hoeper (1998: 334).

87 Steuer (1990: 153). The late-third-century dating of Glauberg is based on the

Wnd of a coin of Tetricus I (ad 271–4): Werner (1965: 87–8). However, coins of this

type remained in circulation until around 300: Drinkwater (1987: 202).

88 For variations in size and likely use see Fingerlin (1990: 136), (1997: 126); Steuer

(1997a: 158); Hoeper (1998: 341–3).

Settlement 95

their militar y entourages, with their families, and separate quarters

for dependent artisans. It has been suggested (using names taken

from Ammianus Marcellinus) that the Za

¨

hringer Burgberg may

have been the residence of Gundomadus or Vadomarius, and the

Glauberg that of a king of the Bucinobantes.89 As in the case of the

rural settlements, buildings were probably simple timber structures,

which rotted away completely in the course of time.90 The lesser hill-

sites have been interpreted as subordinate elements in local power

structures.91 Such a model is derived from Ammianus Marcellinus’

description of the hierarchy of Alamannic kings and nobles in the

mid-fourth century.92 This is plausible. Ammianus’ account of Ala-

mannic society is consistent with barbarian society in general;93 and

there is no reason to suppose that it was subject to much change. As

Hoeper says, though we cannot be certain that the Runder Berg was

the seat of a rex, this seems likely.94

However, the interpretation of archaeological data directly from

historical data is not without problems. There is no direct connection

between Ammianus’ Alamannic rulers and the hill-sites;95 and it has

to be conceded that hill-sites cannot be securely identiWed in his

narrative. The nearest he comes to describing them are his ambigu-

ous accounts of the defended ‘lofty height’ at Solicinium, stormed by

Valentinian I’s army in 368, and the ‘sheer rocks’ defended by ‘obs-

tacles like those of city walls’ encountered by Gratian in his attack on

the Lentienses in 378.96 Most striking is the absence of any mention

of such structures in Ammianus’ narratives of Julian’s close dealings

with a series of Alamannic chiefs in 357–9.97 Ammianus has

his problems as a source,98 but his omission of hill-sites seems to

reXect an authentic historical phenomenon. Mapping known or

89 Za

¨

hringer Burgberg: Fingerlin (1990: 136), (1997: 127); cf. Steuer (1997a: 158);

Hoeper (1998: 334). Glauberg: Werner (1965: 895). Cf. below 173–4, 206.

90 Steuer (1990: 169, 196).

91 Steuer (1997a: 149–51).

92 Below 118.

93 Elton (1996a: 32–3).

94 Hoeper (1998: 330–1).

95 Fingerlin (1993: 72).

96 AM 27.10.8–9: mons praecelsus. Cf. Matthews (1989: 311–12). AM 31.10.12–13:

velut murorum obicibus. Cf. Haberstroh (2000a: 23). Below 282, 288, 311, 314.

97 Below 224–7, 242–3, 246–7.

98 Above 3, below 177–8.

96 Settlement

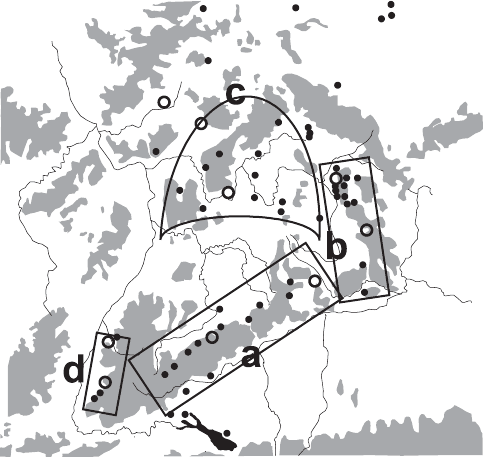

likely hill-sites produces three clear concentrations (Fig. 11): (a)

a narrow line running south-west/north-east, along the Swabian

Alp, north of the upper Danube, inside the old Upper German/

Raetian limes; (b) a narrow line running roughly north/south,

along the Franconian Alp, outside the Upper German/Raetian limes;

(c) a broad crescent spanning the middle Main, from the Odenwald

into the Steigerwald, outside the old Upper German/Raetian limes.

(I will deal with (d), the local concentration in the Breisgau, below.)

These patterns might well represent only the last phase of hill-site

development in the W fth century. However, there are grounds for

believing that they existed earlier. In the Swabian Alp, Runder Berg

(1) was occupied from the early fourth century; and in the Wetterau, a

date of around 300 has been suggested for the Wrst Germanic use of

Glauberg (5). If all three stretches of sites were present in the fourth

century, Julian’s activities in the later 350s would have taken him

Danube

L.Constance

Rhine

Rhine

Moselle

Lahn

Main

Rhine

RegnitzRegnitz

Main

Main

Main

Neckar

Neckar

Neckar

Fig. 11 Known hill-sites: main lines of distribution. Key: a Swabian Alp;

b Franconian Alp (Regnitz area); c Odenwald/Steigerwald/middle Main;

d Breisgau [after Steuer (1990: 144 Fig. 1a)].

Settlement 97