Deza M.M., Laurent M. Geometry of Cuts and Metrics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

13.2 Lattices

and

Delaunay Polytopes

177

on

binary

variables. A well-known (easy) fact is

that

the

polar (PSDn)O

ofPSD

n

consists

of

the

negative semidefinite

quadratic

forms, i.e.,

Hence,

we

have

the

following chain

of

inclusions:

(13.1.8)

This

shows

that

our

central object, namely

the

hypermetric cone (or, to be more

precise,

the

polar

of

its image

under

the

covariance mapping) is a subcone

of

the

cone

of

quadratic

forms

that

are nonpositive

on

binary

variables

and

contains

the

cone -

PSD

n

of

the

quadratic

forms

that

are nonpostive on integer (or real)

variables.

We

will frequently use in

this

chapter

the

graphic metric spaces

attached

to

the

following graphs:

•

the

complete

graph

K

n

,

the

circuit

On,

the

path

P

n

(on n nodes),

•

the

cocktail-party

graph

Knx2

(i.e.,

K2n

with a perfect

matching

deleted),

•

the

hypercube

graph

H(n,

2)

(i.e.,

the

graph

whose nodes are

the

vectors

x E

{o,l}n

with two nodes X,y adjacent

if

del

(x,y)

= 1),

•

the

half-cube

graph

~H(n,

2)

(i.e.,

the

graph

whose nodes are

the

vec-

tors

x E

{o,l}n

with Ll<i<nXi even

and

two nodes X,y are adjacent if

del

(x, y) = 2). - -

13.2

Lattices

and

Delaunay

Polytopes

We give here several definitions related

to

lattices

and

Delaunay polytopes. More

information

can

be found, e.g.,

in

Cassels [1959], Conway

and

Sloane [1988],

Lagarias [1995].

13.2.1

Lattices

A

subset

L of]Rk is called a lattice (or point lattice)

if

L is a discrete

subgroup

of

]Rk,

i.e.,

if

there

exists a ball

of

radius

(J

> ° centered

at

each lattice

point

which contains no

other

lattice point. A subset V

:=

{VI,

...

, v

m

}

of

L is said

to

be generating (resp. a basis) for L if, for every

vEL,

there

exist some integers

(resp. a unique system of integers)

bl,

...

,b

m

such

that

V=

L

biVi·

l:Si:Sm

Every

lattice

has a basis; all bases have

the

same cardinality, called

the

dimension

of

L.

Let

L

<;;;

]Rk

be

a lattice

of

dimension k. Given a basis B

of

L,

let

ME

178

Chapter

13.

Preliminaries on Lattices

denote

the

k x k

matrix

whose rows are the members of

B.

If

Bl

and

B2

are

two bases of

L,

then

MBI

AMB2

where A

is

an

integer

matrix

with

determinant

det(A)

=

±1

(such a

matrix

is

called a

unimodular matrix). Therefore, the quantity I det(B)1 does not depend

on the choice of

the

basis in Lj

it

is called

the

determinant of L

and

is

denoted

by

det(L).

Given a finite set V

~

]Rk, its integer hull

Z(V)

is clearly a lattice whenever

all vectors in

V are rational valued.

Given a vector a E ]Rk, the translate

L'

:=

L + a = {v + a I

VEL}

of a lattice L is called

an

affine lattice. A subset

V'

:=

{vo,

Vl,""

v

m

}

of L' is

called

an

affine generating set

for

L'

(resp.

an

affine basis of

L')

if,

for every

VEL',

there exist some integers (resp. a unique system of integers)

bo,

bl,

...

,

b",

such

that

L

bi

= 1

and

v = L b;vi.

O::;i::;m

O::;i::;=

Clearly,

Viis

an

affine generating set (resp.

an

affine basis) of

L'

if

and

only if

the

set V

:=

{Vl

Vo,

...

,V

m

-

vol

is a (linear) generating set

Crespo

basis)

of

the

lattice

L.

For simplicity,

we

will use the same word "lattice" for denoting

both

a usual

lattice (i.e., containing the zero vector)

and

an

affine lattice (Le., the translate

of a lattice). We also often omit to precise whether

we

consider linear or affine

bases (or generating sets).

Let

L be a lattice.

The

quantity:

t:=

min«u

-

v)21

U,V

E

L,u

# v)

is called

the

minimal

norm

of L. This terminology of minimal "norm"

is

classical

in

the

theory

of

lattices, although

it

actually denotes the square of

the

Euclidean

norm.

In

particular, if 0 E

L,

then

t = mine u

2

I u E

L,

u # 0).

The

minimal

vectors of L are

then

the vectors

vEL

with v

2

t. Their set

is

denoted as L

min

and

the polytope

COnV(Lmin)

is

known as

the

contact polytope

of

L.

Note

that

coincides with the packing radius of

L.

Let L

be

a lattice. Then, L is said

to

be integral if u1'v E Z for all

u,

vEL.

L

is

said to be

an

even lattice if L is integral

and

u

2

E 2Z

for

each u E

L.

L is

called a

root lattice if L is integral

and

L is generated by a set of vectors v

with

v

2

2;

then, each

vEL

with v

2

2 is called a root

of

L.

Observe

that,

in a

root lattice

L,

13.2

Lattices

and

Delaunay Polytopes

179

(13.2.1)

u

T

V

E

{O,

-1,

I}

for all

roots

u,v

of L such

that

u

-I-

±v.

(This

follows from

the

fact

that

(u-v)2

=

4-2u

T

V

> 0

and

(u+v)2

=

4+2u

T

v>

0.)

The

dual L*

of

a

lattice

L

~

~k

is defined as

L * : =

{x

E

~k

I x

T

u E Z for all u E

L}.

If

L is

an

integral lattice,

then

L

~

L * holds. L is

said

to

be

self-dual

if

L = L *

holds. L is

said

to

be

unimodular

if

det(L)

=

±l.

Hence,

an

integral

unimodular

lattice

is self-dual. For example,

the

root

lattice

Es

and

the

Leech

lattice

A24

(introduced

later

in

the

text)

are even

and

unimodular

and, therefore, self-dual.

For every

k-dimensionallattice

L

~

~k

,

(L*)* = L.

Let

L1

and

L2

be

two orthogonal lattices, i.e., such

that

u[

U2

= 0 for all

U1

ELl,

u2 E L

2

.

Their

direct

sum

L1

Ef:l

L2

is

defined by

L is called irreducible if L = L1

Ef:lL2

implies L1 =

{O}

or

L2 =

{O},

and

reducible

otherwise. A well-known result by

Witt

gives

the

classification

of

the

irreducible

root

lattices; cf. Section 14.3.

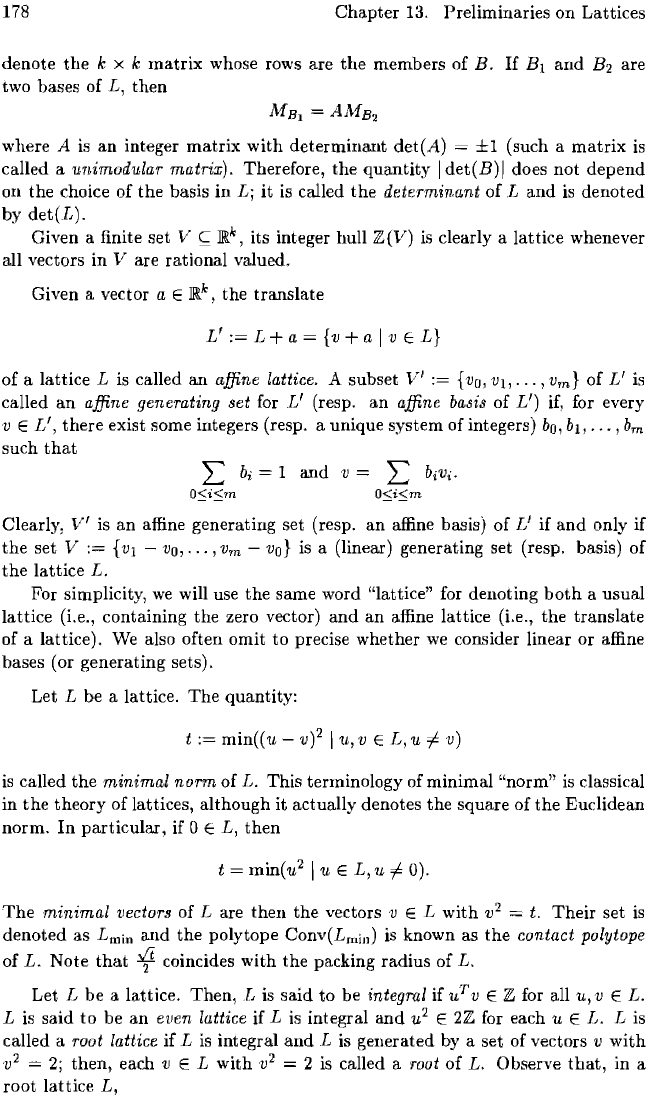

13.2.2

Delaunay

Polytopes

Let

L

~

~k

be

a

k-dimensionallattice

and

let

S =

S(

c,

r)

be

a sphere

with

center

c

and

radius

r

in

~k.

Then,

S

is

said

to

be

an

empty

sphere

in

L if

the

following

two conditions hold:

(i) (v - c)2

~

r2 for all

vEL,

and

(ii)

the

set S n L has affine

rank

k +

l.

Then,

the

center

of

S is called a hole

2

.

The

polytope

P,

which is defined as

the

convex hull

of

the

set

S n

L,

is

called a

Delaunay

polytope,

or

an

L-polytope. See

Figure

13.2.2 for

an

illustration.

Equivalently, a k-dimensional

polytope

P

in

~k

with

set

of

vertices

V(P)

is

a

Delaunay

polytope

if

the

following conditions hold:

(i)

The

set

L(P)

:=

Zaf(V(P))

= { L bvv I

bE

ZV(P), L b

v

=

I}

is

a

vEV(P) vEV(P)

lattice,

(ii) P is inscribed

on

a sphere

S(c,r)

(i.e., (v - c)2 = r2 for all v E

V(P)),

and

(iii) (v - c)2

~

r2 for all v E

L(P),

with

equality if

and

only if v E

V(P).

2The

terminology

of

'empty

sphere'

is used

mainly

in

the

Russian

literature

and

that

of

'hole'

in

the

English

literature.

180

Chapter

13.

Preliminaries on Lattices

Another

equivalent definition will be given in Proposition 14.1.4. Given a De-

launay polytope P, the distance space (V(p),d{2)) is called a

Delaunay polytope

space.

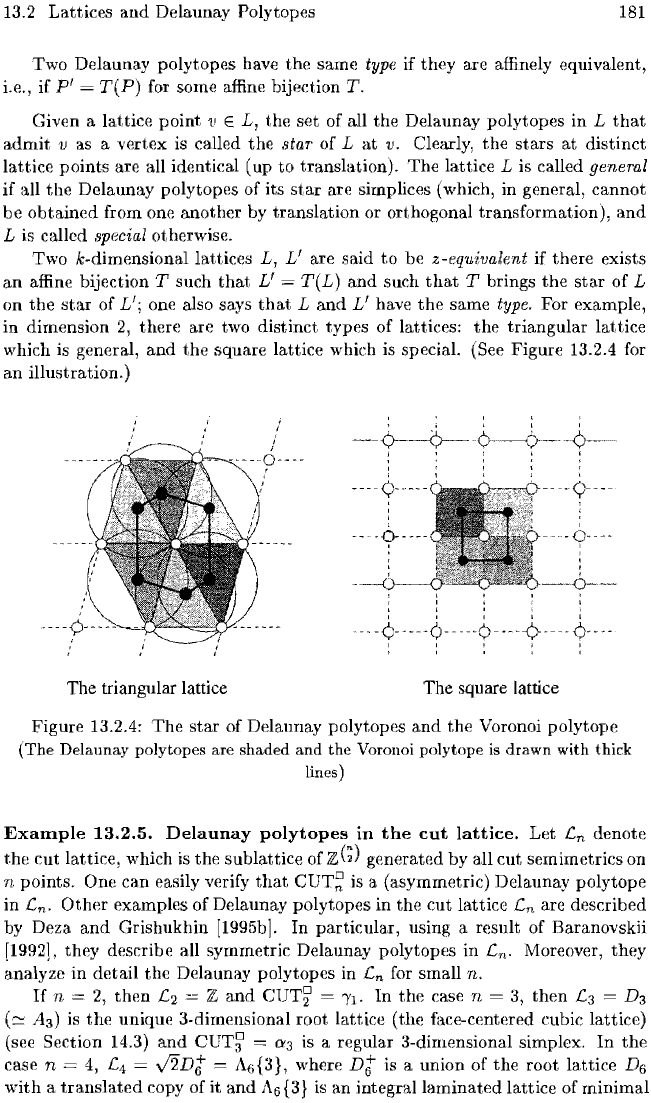

Figure 13.2.2: An empty sphere in a lattice

and

its Delaunay polytope

Let

P be a Delaunay polytope

and

let L be a lattice such

that

V(P)

<;;:

L.

Then,

P

is

said to be generating

in

L if

V(P)

generates

L,

if L

L(P).

There

are examples of lattices for which none

of

their

Delaunay polytopes is

generating; this is the case for the root lattice

E8,

the Leech lattice

Au

and,

more generally, for all even unimodular lattices (see Lemma 13.2.6). However,

when

we

say

that

P is

an

Delaunay polytope

in

L,

we

will always

mean

that

P

is generating in

L,

Le.,

we

suppose

that

L

L(P).

A subset B

<;;:

V(P)

is said

to

be basic if

it

is

an

affine basis of the lattice

L(P).

Then,

P is said to be basic

if

V(P)

contains a basic set, i.e., if

V(P)

contains

an

affine basis

of

L(P).

Actually,

we

do not know

an

example of a

nonbasic Delaunay polytope.

We

formulate this as an open problem for further

reference.

Problem

13.2.3.

Is every Delaunay polytope basic

1"

The

answer is positive for Delaunay polytopes having a small corank

(cf.

Propo-

sition 15.2.12)

and

for concrete examples mentioned later in

Part

II. Some further

information

about

this problem will be given in Section 27.4.3 for Delaunay poly-

topes arising

in

the

context of binary matroids.

The

property of being basic will

be

useful on several occasions; for instance, for formulating upper

bounds

OIl

the

number

of vertices of extreme Delaunay polytopes

(d.

Section 15.3)

or

for the

study

of perfect lattices

(d.

Section 16.5).

For instance,

the

n-dimensional cube

"In

= [0,1]n is a Delaunay polytope

in the integer lattice

zn.

As

other example,

we

have the central object

of

the

book, namely,

the

cut polytope

CUT~,

which is a Delaunay polytope in the

cut

lattice

en

(d.

Example 13.2.5 below). Note

that

both

"In

and

CUT~

are

basic,

"In

is centrally symmetric, while

CUT~

is asymmetric (see

the

definition

in

Lemma

13.2.7).

13.2 Lattices

and

Delaunay Polytopes

181

Two Delaunay polytopes have

the

same type if

they

are affinely equivalent,

i.e.,

if

pI

T(P)

for some affine bijection

T.

Given a lattice

point

v

the

set

of all

the

Delaunay polytopes in L

that

admit

v as a vertex is called

the

star of L

at

v. Clearly,

the

stars

at

distinct

lattice points are all identical (up

to

translation).

The

lattice L is called general

if

all

the

Delaunay polytopes of its

star

are simplices (which, in general,

cannot

be

obtained

from one another by translation or orthogonal transformation),

and

L is called special otherwise.

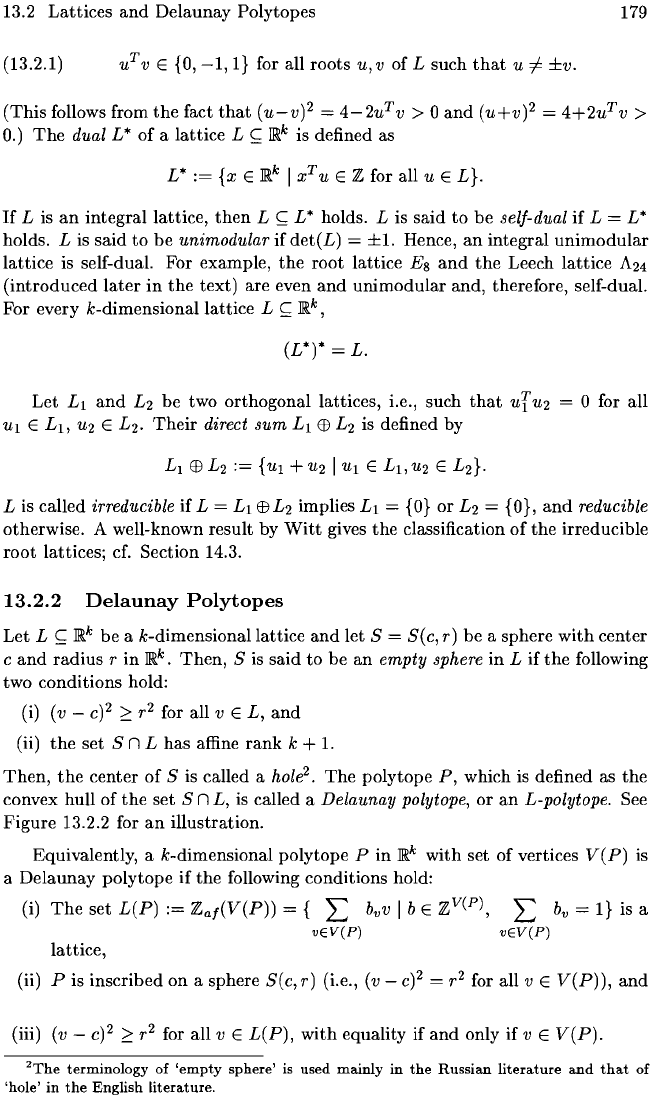

Two k-dimensional lattices

L,

LI are said

to

be

z-equivalent

if

there exists

an

affine bijection T such

that

V

T(L)

and

such

that

T brings

the

star

of L

on

the

star

of V; one also says

that

L

and

V have

the

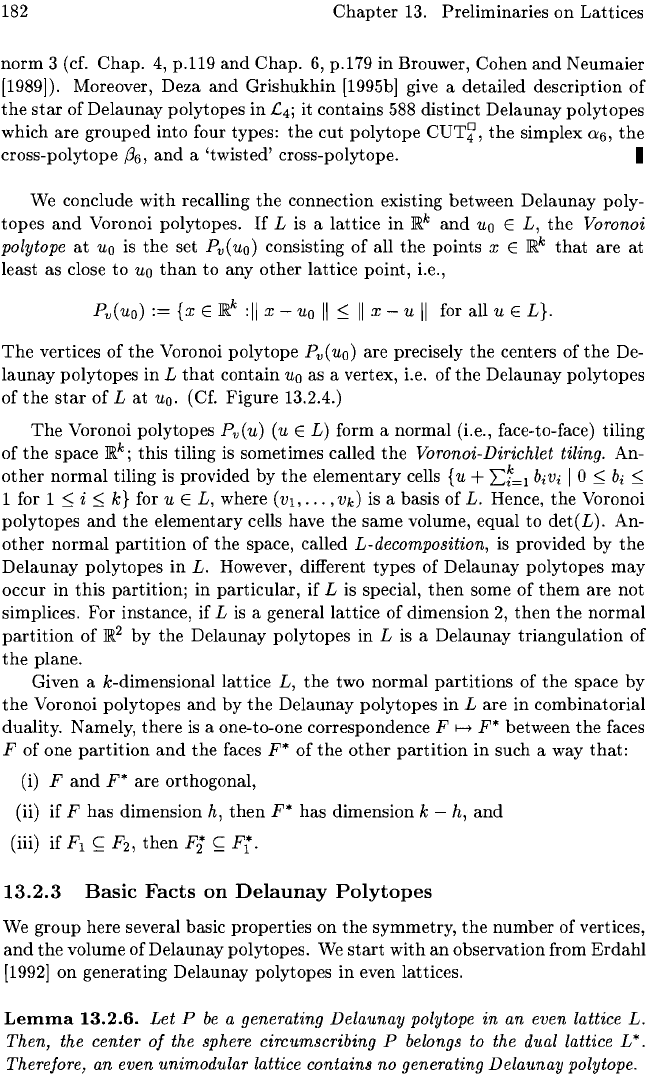

same type. For example,

in dimension

2,

there

are two distinct types of lattices:

the

triangular

lattice

which is general,

and

the

square lattice which is special. (See Figure 13.2.4 for

an illustration.)

The triangular lattice The square lattice

Figure 13.2.4:

The

star

of Delallnay polytopes

and

the

Voronoi polytope

(The

Delaunay

polytopes

are

shaded

and

the

Voronoi

polytope

is

drawn

with

thick

lines)

Exalllple

13.2.5.

Delaunay

polytopes

in

the

cut

lattice.

Let

Ln

denote

the

cut

lattice, which

is

the sublattice of

Z(;)

generated by all

cut

semimetrics on

n points. One can easily verify

that

CUT~

is a (asymmetric) Delaunay polytope

in

Ln.

Other

examples of Delaunay polytopes in

the

cut

lattice Ln are described

by Deza

and

Grishukhin [1995b]. In particular, using a result of Baranovskii

[1992]' they describe all symmetric Delaunay polytopes in

Ln. Moreover,

they

analyze in detail

the

Delaunay polytopes in Ln for small n.

If

n

2,

then

L2

Z

and

CUT~

11. In

the

case n =

3,

then

L3

=

D3

(::::::

A

3

)

is

the

unique 3-dimensional root lattice (the face-centered cubic lattice)

(see Section 14.3)

and

0'3

is

a regular 3-dimensional simplex.

In

the

case n 4, ViDt A6{3}, where Dt is a union of the

root

lattice

D6

with

a

translated

copy of

it

and

A6

{3}

is

an integral laminated lattice of minimal

182

Chapter

13. Preliminaries

on

Lattices

norm

3

(cf.

Chap.

4,

p.119

and

Chap.

6,

p.179 in Brouwer, Cohen

and

Neumaier

[1989]). Moreover, Deza

and

Grishukhin [1995b] give a detailed description

of

the

star

of Delaunay polytopes in £4; it contains 588 distinct Delaunay

polytopes

which are

grouped

into four types:

the

cut

polytope

CUT?,

the

simplex

0:6,

the

cross-polytope

(36,

and

a

'twisted'

cross-polytope. I

We conclude

with

recalling

the

connection existing between Delaunay poly-

topes

and

Voronoi polytopes.

If

L is a

lattice

in

Rk

and

Uo

E

L,

the

Voronoi

polytope

at

Uo

is

the

set P

v

(uo)

consisting

of

all

the

points

x E

Rk

that

are

at

least as close to

Uo

than

to any

other

lattice point, i.e.,

Pv(uo)

:=

{x

E

Rk

:11

x -

Uo

II

~

II

x - u

II

for all u E

L}.

The

vertices of

the

Voronoi

polytope

Pv(uo) are precisely

the

centers of

the

De-

launay

polytopes

in

L

that

contain

Uo

as a vertex, i.e. of

the

Delaunay

polytopes

of

the

star

of

L

at

Uo.

(Cf.

Figure

13.2.4.)

The

Voronoi polytopes Pv(u)

(u

E L) form a

normal

(i.e., face-to-face) tiling

of

the

space Rk; this tiling is sometimes called

the

Voronoi-Dirichlet tiling. An-

other

normal

tiling

is

provided by

the

elementary cells

{u

+

I:f=l

bivi I 0

~

bi

~

1 for 1

~

i

~

k}

for u E

L,

where

(VI,

...

,Vk)

is a basis of

L.

Hence,

the

Voronoi

polytopes

and

the

elementary cells have

the

same

volume, equal to

det(L).

An-

other

normal

partition

of

the

space, called L-decomposition,

is

provided by

the

Delaunay

polytopes

in

L. However, different types of Delaunay

polytopes

may

occur in

this

partition;

in

particular,

if L is special,

then

some

of

them

are

not

simplices. For instance, if L

is

a general lattice of dimension

2,

then

the

normal

partition

of

R2

by

the

Delaunay polytopes in L is a Delaunay

triangulation

of

the

plane.

Given a

k-dimensionallattice

L,

the

two

normal

partitions

of

the

space

by

the

Voronoi polytopes

and

by

the

Delaunay polytopes

in

L are

in

combinatorial

duality. Namely,

there

is

a one-to-one correspondence F

f->

F*

between

the

faces

F of one

partition

and

the

faces

F*

of

the

other

partition

in

such a way

that:

(i) F

and

F*

are orthogonal,

(ii) if

F has dimension

h,

then

F*

has

dimension k -

h,

and

(iii) if

FI

C;;;

F2,

then

F2*

C;;;

Fi-

13.2.3

Basic

Facts

on

Delaunay

Polytopes

We

group

here several basic properties

on

the

symmetry,

the

number

of vertices,

and

the

volume of Delaunay polytopes. We

start

with

an

observation from

Erdahl

[1992]

on

generating Delaunay polytopes in even lattices.

Lemma

13.2.6.

Let

P

be

a generating Delaunay polytope in an even lattice

L.

Then, the center

of

the sphere circumscribing P belongs to the dual lattice

L·.

Therefore, an even unimodular lattice contains no generating Delaunay polytope.

13.2 Lattices

and

Delaunay Polytopes

183

Proof.

We

can

suppose

that

the

origin

is

a vertex of

P.

Let

c denote the center

of

the

sphere S circumscribing

P.

Since L

is

generated by

V(P),

it

suffices to

check

that

c

T

v E Z for each v E

V(P),

for showing

that

c E L*. For v E

V(P),

(c

-

v)2

= c

2

, i.e.,

2c

T

v v

2

,

implying

that

E Z since v

2

is even.

If

L

is

even

unimodular,

then

c E

L*

=

L,

contradicting the fact

that

S

is

an

empty

sphere

in

L.

I

Let S be a sphere

with

center c. For

XES,

its antipode

on

S

is

the

point

x'

:=

2c - x.

It

is

immediate

to

see

that:

Lemma

13.2.7.

For a Delaunay polytope

P,

one

of

the following assertions (i)

or (ii) holds.

(i)

v*

E

Y(P)

for all v E

V(P).

(ii)

v*

f/.

V(P)

for all v E

V(P).

I

In

case (i),

we

say

that

P is centrally

symmetric

3

and, in case (ii),

that

P

is

asymmetric.

Proposition

13.2.8.

Every Delaunay polytope P

in:IR

k

has

at

most

2k

vertice.5.

Proof.

Without

loss

of

generality,

we

can suppose

that

the

origin is a vertex of

P. Let

{VI,

...

,vA:}

be a basis of the lattice L =

L(P).

We

consider

the

following

equivalence relation on

L: For u,

VEL,

set u

'"

v if u + v E 2L. Clearly, every

vertex of

P

is

in relation by

'"

with one of

the

elements

LiEf

vi

for I

:;;

{I,

...

, k

}.

On

the

other

hand, no two vertices

of

P are in relation by

"'.

Indeed,

if

u

'"

v for

11.,

'U

E

V(P),

then

E

L,

contradicting

the

fact

that

the sphere circumscribing

P is

empty

in L. shows

that

P has

at

most

2k

vertices. I

Let

11.,

v, w be vertices of a Delaunay polytope P. One can check

that

(13.2.9)

This

is

the

triangle inequality, expressing the fact

that

the

Delaunay polytope

space

(V(P),

d(2))

is a semi metric space. Actually,

we

will see in Proposi-

tion

14.1.2

that

every Delaunay polytope space

is

hypermetric, which is a much

stronger property.

The

inequality (13.2.9) means

that

the

points u, 'U, w form a

triangle

with

no obtuse angles.

The

problem of determining the

maximum

car-

dinality

of

a

set

points in

:IRk,

any three of which form a triangle with no obtuse

angle, was first posed by Erdos [1948, 1957], who conjectured

that

this maxi-

mum

cardinality is

2k.

This conjecture was proved by Danzer

and

Griinbaum

[1962]. Therefore,

the

inequality (13.2.9) is already sufficient for proving

the

upper

bound

2k

on

the

number of vertices

of

a Delaunay polytope in

:IRk.

coincides

with

the

definition given earlier for centrally symmetric sets,

up

to

a trans-

lation

of

the

center of

the

sphere circumscribing P

to

the

origin.

184

Chapter

13.

Preliminaries on Lattices

The

following

upper

bound

on

the

volume

of

a Delaunay polytope was ob-

served by Lovasz

[1994].

Proposition

13.2.10.

Let

P

be

a Delaunay polytope in a lattice L with volume

vol(P).

Then,

vol(P)

S

det(L).

Proof.

The

bound

vol(P) S det(L) follows from

the

fact

that

the polytopes

P+u

(u E L) form a packing. i.e.,

that

their interiors are pairwise disjoint. I

13.2.4

Construction

of

Delaunay

Polytopes

Clearly, every face

of

a Delaunay polytope is again a Delaunay polytope (in

the space affinely spanned by

that

face).

We

present here some further meth-

ods for constructing Delaunay polytopes; namely, by taking suitable sections of

the

sphere

of

minimal vectors in a lattice, by direct

product

and

by

pyramid

or bipyramid extension.

We

then

give the complete classification

of

Delaunay

polytopes in dimension

k S 4.

Construction

by

Sectioning

the

Sphere

of

Minimal

Vectors

in

a

Lattice.

Let L be a lattice in

lRI,k

with

0

ELand

let

Lmin

be

the

set

of

minimal vectors

of

L.

Given noncollinear vectors a,

bE

lRI,k

and

some nonzero scalars

0:,

/3,

set

The

following construction, taken from Deza, Grishukhin

and

Laurent [1992J,

can

be easily checked;

it

will

be

applied

on

several occasions in Sections 16.2,

16.3

and

16.4.

Lemma

13.2.11.

If

the sets

Va

and

Va

n

Vi,

are

not

empty, then the polytopes

Conv(Va)

and

Conv(V

a

n

Vi,)

aTe

Delaunay polytopes. I

Direct

Product.

Let

Li

be

a lattice in

IRki

and

let Pi

be

a Delaunay polytope

in

Li

centered

at

the origin whose circumscribed sphere has radius

ri,

for i =

1,2.

Then,

L XL2

{(vt,VZ)IVIELl,V2EL2}

is a lattice in

(k

kJ

+

k2)

and

is a Delaunay polytope in L whose circumscribed sphere is centered in

the

origin

and

has radius

l'

V

rI

+

r~.

Therefore, the direct

product

of

two Delaunay

polytopes

is

again a Delaunay polytope.

The

direct product

of

P

and

a segment

0:1 is called

the

prism

with base

P.

13.2 Lattices

and

Delaunay Polytopes

185

Call a Delaunay polytope reducible

if

it

is

the

direct

product

of

two

other

nontrivial (Le.,

not

reduced

to

a

point)

Delaunay polytopes

and

irreducible oth-

erwise. Note

that

irreducible Delaunay polytopes arise

in

irreducible lattices.

Pyramid

and

Bipyramid.

Let

P

be

a polytope

and

let v

be

a

point

that

does

not

lie

in

the

affine space spanned by

P,

then

pyrv(P)

:=

Conv(P

U

{v})

is called

the

pyramid

with base P

and

apex v. Under some conditions,

the

pyramid

of

a Delaunay polytope

is

still a Delaunay polytope.

Namely, let P

be

a Delaunay polytope with

radius

r, suppose

that

v is

at

squared

distance

t from all

the

vertices of P

and

that

t > 2r2.

Then,

the

pyramid

Pyrv(P)

is a Delaunay polytope with radius R (see

Proposition

14.4.6).

Moreover, if P

is

centrally symmetric

and

if t

then

the

bipyramid

Conv(PU

{v,v*})

is a Delaunay polytope with radius r, where

v*

is

the

antipode

of

von

the

sphere

circumscribing

Pyrv(P)

(see Proposition 14.4.6).

The

Layerwise

Construction.

The

following layerwise construction for Delaunay

polytopes

is

described in Ryshkov

and

Erdahl

[19891.

In fact,

rather

than

a construction,

it

is

a way

of

visualizing a given k-dimensional Delaunay polytope in a

lattice

L as

the

convex hull of its sections by

the

(k - I)-dimensional layers composing L.

Let

L be a k-dimensional lattice

and

let be a basis of L.

Then,

Lo

:=

Z(VI,

...

,

Vk-l)

is

a (k - I)-dimensional

sublattice

of

Land

L UaEZ(Lo +

aVk).

The

layers

Lo

+

aVk

(a

E

Z)

are

affine

translates

of

Lo

lying in parallel hyperplanes.

Let

P be a k-dimensional Delaunay polytope, let L denote

the

lattice

generated by

Yep),

and

let

S be

the

sphere circumscribing P.

Let

F

be

a facet

of

P and let H

denote

the

hyperplane

spanned

by F.

Then,

Lo

:=

L n H

is

a (k I)-dimensional

sublattice

of

Land

L

is

composed by

the

layers

Lo

+ av (a E

Z)

for some

vEL

Lo. Therefore,

P Conv(UaEZ( S n

(Lo

+

av))),

where S n

Lo

is

the

set of vertices

of

F

and,

for a E Z,

S n

(Lo

+

av)

is

empty

or

is

the

set of vertices of a face

of

a Delaunay polytope in L

o

.

So,

we

have

the

following result:

Proposition

13.2.12.

For each k-dimensional Delaunay polytope

P,

there exists a

(k

I)-dimensional

lattice Lo, an integer p

2:

1, and a sequence

Fo,

F

I

,

•.

. ,

of

poly-

topes that are faces

of

Delaunay polytopes in

Lo

(where dim(Fo) = k

1.

but

...

,

Fp

may

be

empty)

such that P =

Conv(Uo~a~p(Fa

+ av»), where v is a vector

not

lying

in

the space spanned by Lo· I

For instance,

the

pyramid construction can be viewed as

the

above layerwise con-

struction

with p 1, with a facet on

the

layer

Lo

and

a single point on

the

layer

Lo

+ v.

Let

p(k)

denote

the

smallest number p of polytopes

H,

...

,Fp

in Proposition 13.2.12

needed for

constructing

any

k-dimensional Delaunay polytope.

Given a

lattice

L, if P is a Delaunay polytope in L which is a simplex,

then

its

volume

is

an

integer multiple of

de~\L)

(this

can

be checked by induction on

the

dimension).

This

integer

is

called

the

relative volume of

the

simplex

P.

The

maximum relative volume

186

Chapter

13.

Preliminaries

on

Lattices

of

all simplices

that

are

Delaunay

polytopes

in

any

k-dimensional

lattice

is

denoted

by

pork).

It

is shown in

Ryshkov

and

Erdahl

[1989]

that

p(k) = pork) holds.

In

particular,

p(2) = p(3) = p( 4) = 1, p(5) = 2

and

L

k;-1

J

:::;

p(k)

:::;

kL

There

is a

Delaunay

polytope

of

dimension 6,

namely

the

Schliifli

polytope

2

21

,

for

which

the

integer

p

(from

Proposition

13.2.12) satisfies p > 1.

In

fact, for 2

21

,

P = 2, i.e.,

three

layers

are

needed

to

obtain

221

from its 5-dimensional sections. We

mention

two

ways

of

visualizing

221

via

the

layerwise

construction.

In

the

first

construction,

Lo

is

the

root

lattice

D5

and

the

layers Lo,

Lo

+ v,

Lo

+ 2v carry, respectively,

Fo

=

(35,

Fl = h"l5

(the

5-dimensional

half-cube)

and

F2

which is a single point.

In

the

second

construction,

Lo

is

the

root

lattice

A5

and

the

layers carry, respectively,

Fo

= a5, Fl = J(6,2)

and

F2

= a5.

We

refer

to

Coxeter

[1973] for a

description

of

all faces

of

2

21

.

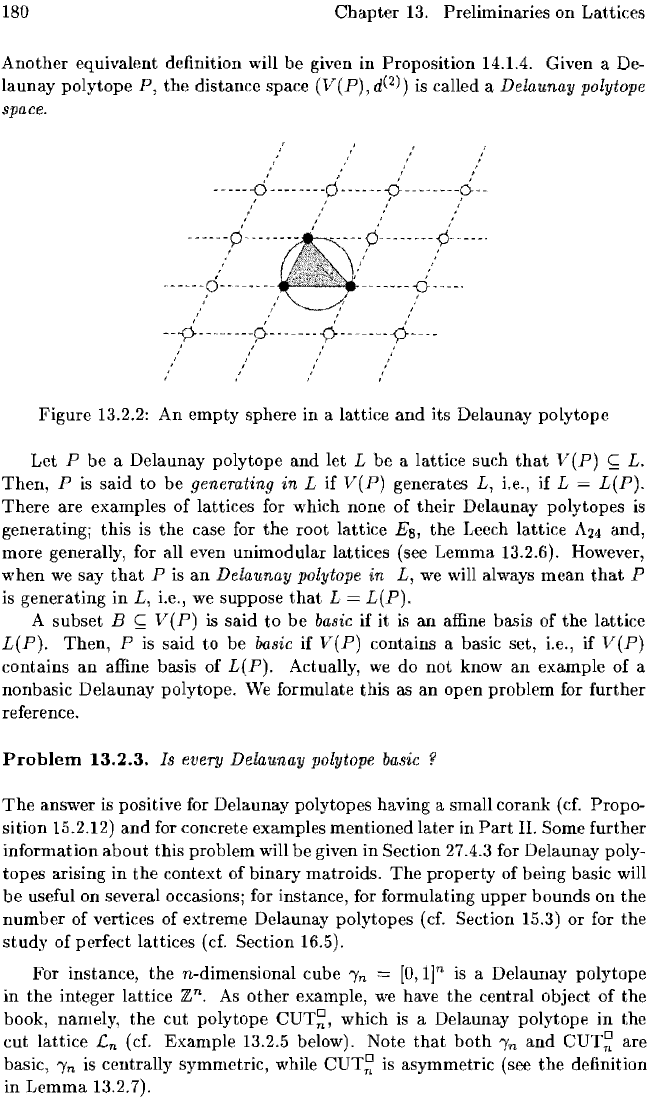

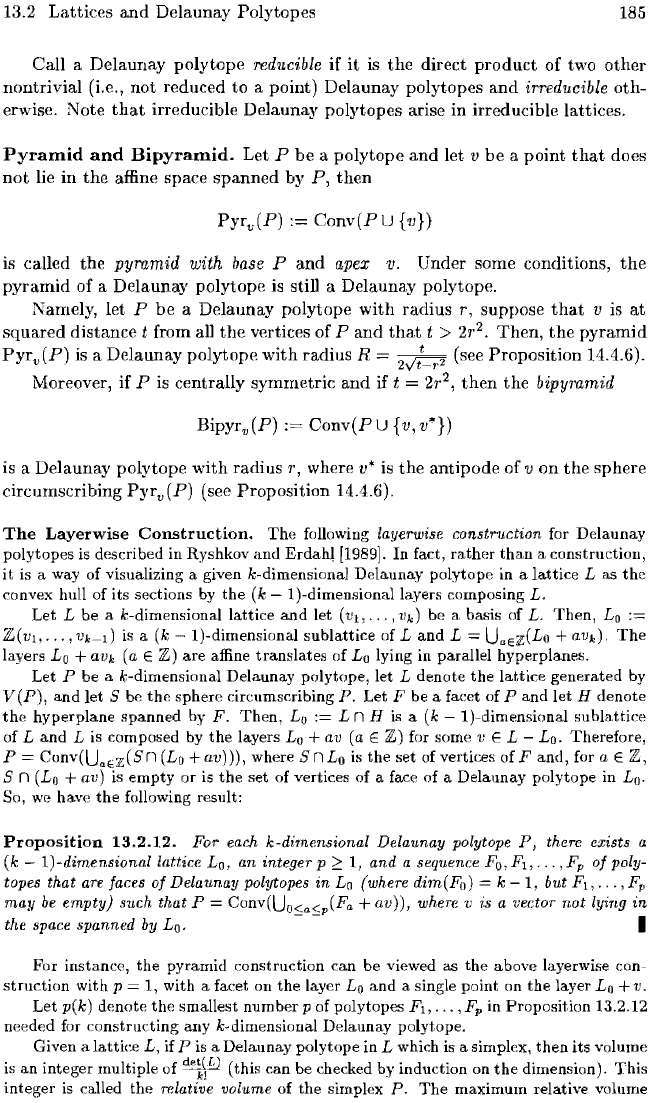

The tetrahedron The octahedron The cube

The prism (with triangular base) The pyramid (with square base)

Figure

13.2.13:

The

five

types

of

Delaunay

polytopes

in

dimension

3

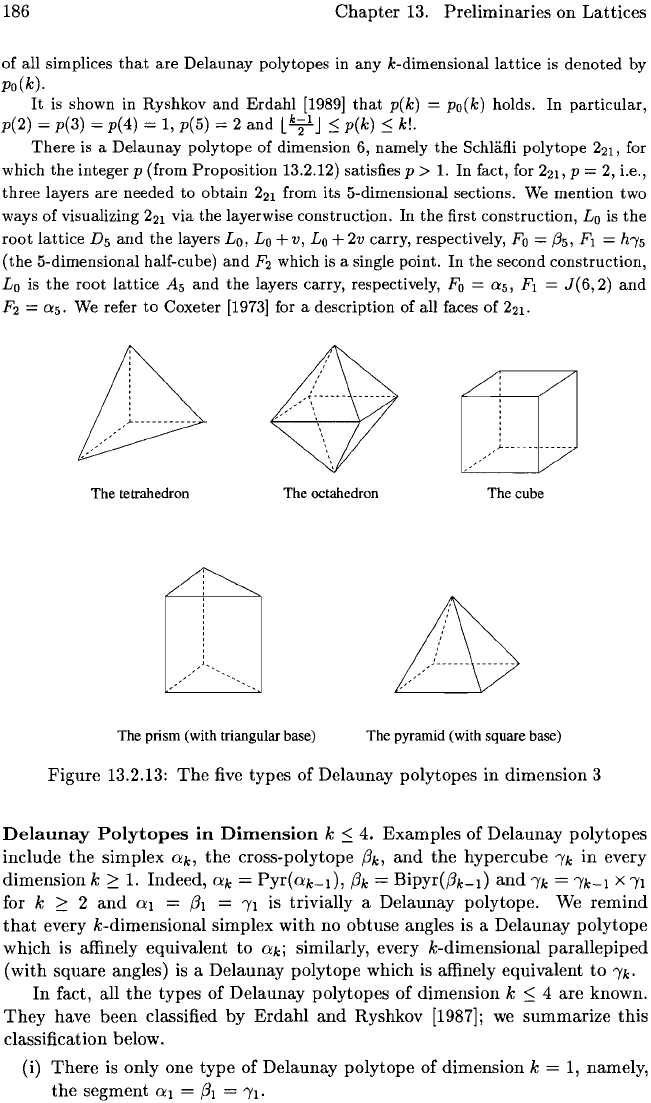

Delaunay

Polytopes

in

Dimension

k

:::;

4.

Examples

of

Delaunay

polytopes

include

the

simplex

OCk,

the

cross-polytope

(3k,

and

the

hypercube

Ik

in

every

dimension

k

2:

1.

Indeed,

OCk

= Pyr(ock_I), (3k = Bipyr((3k-l)

and

Ik

=

Ik-l

X

II

for k

2:

2

and

OCI

=

(31

=

11

is

trivially

a

Delaunay

polytope.

We

remind

that

every

k-dimensional

simplex

with

no

obtuse

angles is a

Delaunay

polytope

which

is affinely

equivalent

to

OCk;

similarly, every

k-dimensional

parallepiped

(with

square

angles) is a

Delaunay

polytope

which

is affinely

equivalent

to

Ik.

In

fact, all

the

types

of

Delaunay

polytopes

of

dimension

k

:::;

4

are

known.

They

have

been

classified

by

Erdahl

and

Ryshkov

[1987]; we

summarize

this

classification below.

(i)

There

is

only

one

type

of

Delaunay

polytope

of

dimension

k = 1, namely,

the

segment

OCI

=

(31

= 11·