Deza M.M., Laurent M. Geometry of Cuts and Metrics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

124

Chapter

9.

Metric 'Transforms of

Ll-Spaces

Proof.

First,

c2(6)

;:::

~h(6)

=

h(2).

Equality

is

proved, by considering

the

path

metric

d of K

3

,3.

Indeed, if a >

~,(2),

then

d

2

'"

is

not

6-gonal

and,

thus,

not

of

negative type.

That

is,

d'"

is

not

f

2

-embeddable. I

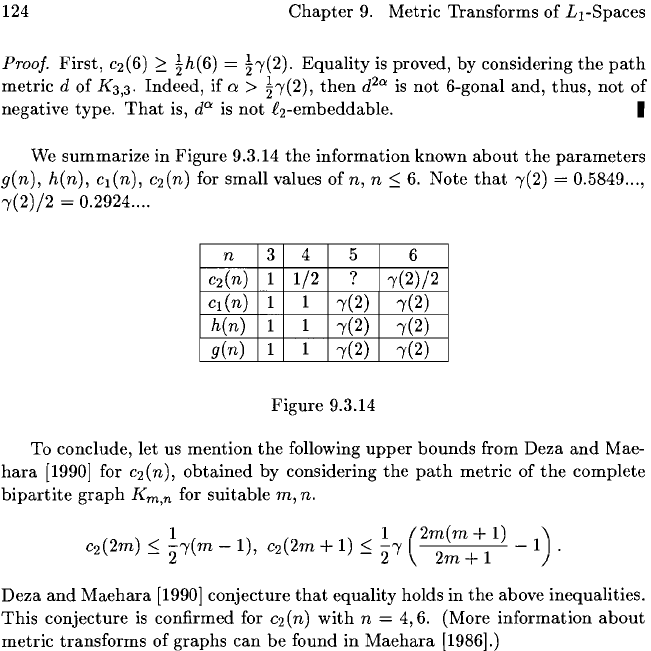

We

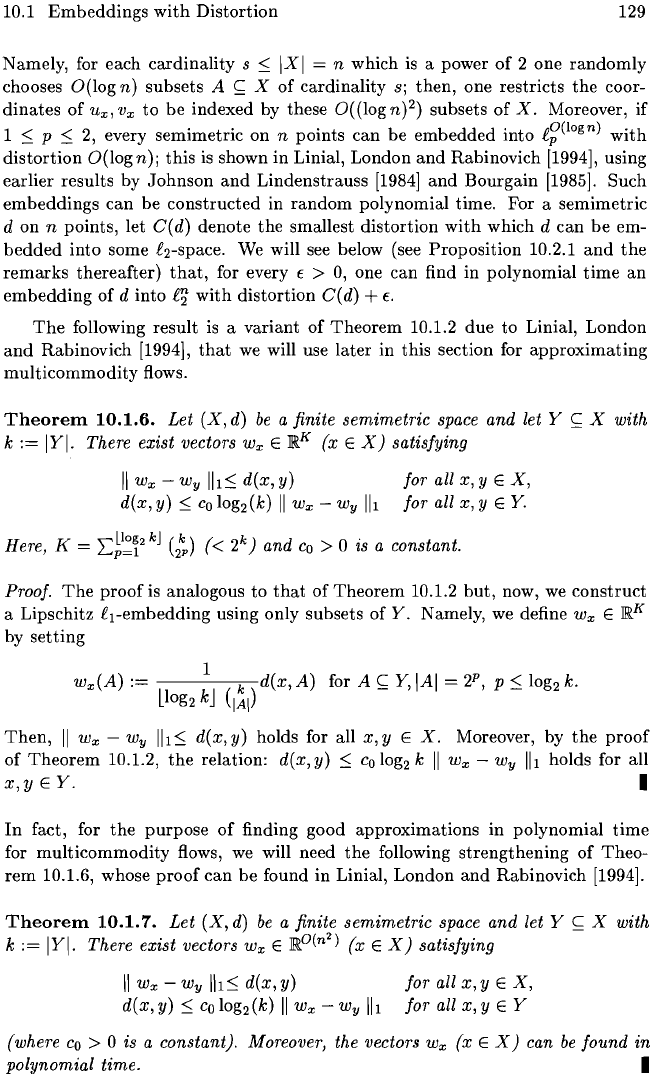

summarize

in

Figure

9.3.14

the

information known

about

the

parameters

g(n), h(n), cl(n), c2(n) for

small

values

ofn,

n:S;

6.

Note

that

,(2)

= 0.5849 ... ,

,(2)

/2

= 0.2924 ....

n

3 4 5

6

c2(n)

1

1/2

?

,(2)/2

Cl

(n)

1

1

,(2)

,(2)

h(n) 1

1

,(2)

,(2)

g(n) 1

1

,(2)

,(2)

Figure

9.3.14

To conclude, let us

mention

the

following

upper

bounds

from Deza

and

Mae-

hara

[1990]

for c2(n),

obtained

by considering

the

path

metric of

the

complete

bipartite

graph

Km,n for suitable

m,

n.

1 1

(2m(m

+

1)

)

c2(2m)

:s;

Z,(m

- 1), c2(2m +

1)

:s;

Z,

2m + 1 - 1 .

Deza

and

Maehara

[1990]

conjecture

that

equality holds in

the

above inequalities.

This

conjecture

is

confirmed for

C2

(n)

with

n = 4,6. (More

information

about

metric

transforms

of graphs

can

be

found

in

Maehara

[1986].)

M.M. Deza, M. Laurent, Geometry of Cuts and Metrics, Algorithms and Combinatorics 15,

DOI 10.1007/978-3-642-04295-9_10, © Springer-Verlag Berlin Heidelberg 2010

Chapter

10.

Lipschitz

Embeddings

Let

(X,

d)

be

a finite semimetric space on n

:=

IXI

points. In general, (X,

d)

cannot

be

isometrically

embedded into some

i\

-space. However,

(X,

d)

admits

always

an

embedding

into

some

1\

-space, where

the

distances are preserved

up

to

a multiplicative factor whose size is

of

the

order log n.

This

result is due

to

Bourgain [1985]. We present this result, together

with

an

interesting application

due to Linial, London

and

Rabinovich

[1994]

for approximating multicommod-

ity flows. We also present a generalization of

the

negative

type

condition for

Lipschitz

f

2

-embeddings.

10.1

Embeddings

with

Distortion

Definition

10.1.1.

Let

(X,

d)

and

(X',

d')

be

two

distance spaces

and

let C

~

l.

A

mapping

<.p

: X

~

X'

is called a Lipschitz embedding

of

(X,

d)

into

(X',

d')

with

distortion

C

if

~d(X'Y)

~

d'(<.p(x),<.p(y))

~

d(x,y)

holds

for

all

x,

y

EX.

Hence, a Lipschitz embedding

with

distortion

C = 1

is

just

an

isometric embed-

ding.

Bourgain

[1985]

shows

that

every semimetric space

on

n

points

admits

a

Lipschitz

embedding

into f1

with

distortion

1

O(log2(n)).

Theorem

10.1.2.

Let

(X,

d)

be

a

finite

semimetric

space

with

IXI

=

n.

There

exist

vectors

U

x

E

jRN

(x

EX)

satisfying:

II

U

x

-

U

y

III

~

d(X,

y)

~

Co

log2(n)

II

U

X

-

u

y

III

for

all

x,

y

EX.

Here, N =

L~~12

nJ

G;')

« 2

n

),

and

Co

> 0 is a

constant.

lThe

Lipschitz

embedding

described

in

Theorem

10.1.2

has

distortion

Co log2

n,

where

Co <

92.

Garg

[1995b]

presents

a slight

variation

of

it,

for which

he

can

show a

better

constant

for

the

distortion.

Namely,

set

H(n)

:=

1 + t + ... +

~

and,

for x E

X,

let

u~

be

the

vector

indexed

by

all

proper

subsets

A

of

X

with

components

u~(A):=

d(Z'"()n

).

Then,

H(n)IAI

IAI

II

u~

-

u~

111::;

d(x,y)::;

2H(n)

II

u~

-

u~

111

for all

x,y

EX.

126

Chapter

10. Lipschitz

Embeddings

Proof. For each

integer

s

(1

::;

s

::;

n)

let P

s

denote

the

family

of

subsets A

<:;;

X

with

IAI

=

s.

Set P

:=

U~~~2nJ

P

2

p;

so

IPI

=

N.

For

each

x E

X,

we define

the

vector

U

x

E

ffiN

indexed by

the

sets A E P

and

defined by

1

ux(A)

:=

II

J

(n)

d(x, A), for all A E P.

og2

n

IAI

We

remind

that

d(x, A)

:=

miIlyEA

d(x, y). We show

that

the

vectors U

x

(x E

X)

satisfy

the

conditions

of

Theorem

10.1.2. We first check

that

d(x,y):2:llu

x

-u

y

lll

forallx,yEX.

Indeed, using

the

fact

that

Id(x, A) - d(y, A)I

::;

d(x, y), we

obtain

= L

IUx(A)

- uy(A)1 = 1 L Id(x, A) : d(y, A)I

AE'P

llog2

nJ

AE'P

(IAI)

1

"d(x,

y)

::;

Llog2

n

J

L...J

-(

n) = d(x,y).

AE'P

IAI

Let

x,

y E X

be

fixed. We now show

that

(10.1.3)

for some

constant

Co.

For

Zo

E X

and

P > 0, let B(zo,

p)

:=

{z

E X I d(zo, z) <

p}

denote

the

open

ball

with

center

Zo

and

radius

p.

We define a sequence

of

radii

Pt

in

the

following way:

Po

:=

0

and,

for t

:2:

1,

Pt

denotes

the

smallest

scalar

P

for which IB(x,p)1

:2:

2t

and

IB(y,p)1

:2:

2t. We define

Pt

as long as

Pt

<

~d(x,y).

Let

t*

denote

the

largest such index. We let

Pt*+l

:=

~d(x,y).

Observe

that,

for

t =

1,2,

...

,t*,

t*

+ 1,

the

balls

B(x,

Pt)

and

B(y,

Pt)

are

disjoint.

Let

t E

{I,

...

,t*

+

I}

and

let P

be

such

that

Pt-l < P <

Pt.

Note

that

Id(x, A) - d(y, A)I

:2:

P - Pt-l

holds for

any

subset

A

<:;;

X

such

that

An

B(x,

p)

= 0

and

An

B(y,

pt-d

i-

0.

Hence, for

any

integer s

(1

::;

s

::;

n),

(10.1.4)

If'l

L

Id(x,A)-d(y,A)1

AE'P,

>

(p

- P )

I{AE'P,IAnB(x,p)=0,AnB(y,pt-l);l011

=

(p

- Pt-l)lI.

t

,

_

~l

I~I

r

after

setting

I{A E

Psi

AnB(x,p)

=

0,AnB(y,pt-d

i-

0}1

J.Lt:=

IPsl

.

The

key

argument

is now

to

observe

that,

if

we

choose s

in

such a way

that

s

::::;

lO~2t'

then

the

quantity

J.Lt

is

bounded

below by

an

absolute

constant

J.Lo

(not

depending

on

t, x

or

y). More precisely, let

us

choose s =

St

= 2

P

,

where p is

10.1 Embeddings

with

Distortion

127

the

smallest integer such

that

:::;

21',

i.e., p =

l1og2(10~2,)1.

Let us assume

for a

moment

that

the relation

/-tt

/-to

holds for all t, for some constant

/-to.

We

show how to conclude the proof

of

(10.1.3).

As

the values of

o5t

corresponding

to

t = 1,

...

,

t*

+ 1 are all distinct,

by

applying (10.1.4)

with

05

o5t,

we

deduce

that

1

-IP

I L Id(x,A) d(y,A)1

?,(p-Pt-I)/-tO'

s,

AE1'.,

Letting

P

---t

Pt,

the

same relation holds

with

P

Pt,

i.e.,

1

-IP

I L Id(x,A)

d(y,A)I?

(Pt

Pt-I)/-tO.

8, AE1'"

Summing the above relation over t

1,

...

,

t*

+

1,

we

obtain:

Llogz

nJ

II

U

X

-

u

y

Ill?

L

(Pt

Pt-I)/-tO

lS:tS:t'

+I

/-to

)

Pt'+I/-tO

=

Td(x,y

.

This

shows

that

(10.1.3) holds

with

Co

:=

(Note

that

Co

< 91.26.)

PO

Let us

return

to the evaluation of the quantity

/-tt.

Recall

that

05

=

o5t

=

21',

where p = f!ogz(

1O~2dl;

hence,

lO~z'

:::;

S < As

Pt-l

< P <

Pt,

we

have

IB(x,p)1 <

2t

or IB(y,p)1 <

2t.

We

can

suppose without loss of generality

that

IB(x,p)1 <

2t.

Set

,8

x

:=

IB(x,p)1

and

fly

IB(y,Pt-l)li

then,

flx

<

2t

and

fly

?

2t-l.

We

have:

_

(n-:~)_{n-P:-Py)

/-tt

-

t)

fJz-l

fJ,,+fJ

y

-l

=

II

(l-

_s_.)

-

II

(1

_ _ s_.)

i=O

n-2

i=O

n 2

=

II

(1

__

S

_.)

1-

II

(1

__

S

_.)

•

fJ",-l

(fJ",+/1Y-l

)

i=O

n - 2

i=/1",

n - 2

We

show

that

S

/1~+/1y-l

_.it

d

II

(

S)

1

? e

10

an 1 -

--.

:::;

e -

20

,

i=/3"

n - 2

n

8 1

which implies

that

/-tt

?

e-

lo

(1

-

e-

2O

)

=:

/-to.

Indeed,

/1",-1

II

(1

- S ?

(1

i=O

n

= exp(.8

x

log(1 -

? exp(

-,8

x

n-;f+

1

)

(we have used the fact

that

log(1 - u) ?

-2u

for 0

:::;

u

:::;

~).

Now,

the

latter

quantity

is

greater

than

or equal to exp(

--&),

as S <

15~',

flx

<

2t,

and

128

Chapter

10. Lipschitz

Embeddings

n-;'+l

::;

2.

On

the

other

hand,

/Jx+/J

y

-

1

S S S

s

II

(1--.)::;

(1---)/Jy

= exp(J3

y

log(I---))

::;

exp(-J3

y

--)

i=/Jx

n - z n - J3x n -

J3x

n - J3x

(we have used

the

fact

that

10g(1

- u)

::;

-u

for 0

::;

U

::;

1).

The

latter

quantity

is less

than

or equal to exp( - fa), as

J3

y

2:

2

t

-1, S

2:

1O~2"

and

n!:/Jx

2:

1.

I

Theorem

10.1.2 extends,

in

fact, easily

to

the

case of tp-spaces for p

2:

1, as

observed

in

Linial,

London

and

Rabinovich [1994].

Theorem

10.1.5.

Let

1

::;

p <

00.

Let

(X,

d)

be

a

semimetric

space with

IXI

=

n.

There exist vectors

Vx

E]RN

(x

E

X)

such that

II

Vx

-

Vy

lip::;

d(x,y)

::;

Co

10g2

nil

Vx

-

Vy

lip

for

all

x,

y E

X.

Here, N =

L~~~2nJ

G~)

« 2

n

),

and

co>

0 is a constant.

Proof.

The

vectors

can

be

constructed

by slightly modifying

the

vectors U

x

from

the

proof

of

Theorem

10.1.2. We

remind

that

where

AA

:=

1 for A E P. Define

Vx

E

]RN

by

setting

Llog2

nJ

(I~I)

Observe

that

2:

AA

=

1.

From

this

follows

that

II

VX

-

Vy

lip::;

d(x,y).

By

AE'P

convexity

of

the

function x

f-----7

x

P

(x

2:

0)

we

obtain

that

1

2:

AAld(x, A) -

d(y,

A)I

::;

(2: AAld(x, A) -

d(y,

AW)

P

AE'P AE'P

This

implies

that

II

U

X

-U

y

111::;11

Vx

-V

y

lip'

Thus,

d(x,

y)

::;

Co

10g2

n

II

VX

-Vy

lip,

I

We have

just

seen

that,

for each p

2:

1,

every

semimetric

on n

points

can

be

embedded

with

distortion

O(logn)

into

t{;',

where N < 2n.

In

fact, Linial,

London

and

Rabinovich

[1994]

show

that

the

above proofs

can

be modified so

as

to

yield

an

embedding

into

t~((logn)2)

with

distortion

O(logn).

Hence,

the

embedding

takes place

in

a space

of

dimension o ((log n )2)

instead

of

the

di-

mension

N =

Lp

G~)

(exponential

in

n)

demonstrated

in

Theorems

10.1.2

and

10.1.5. For this,

instead

of

the

vectors U

x

,

Vx

(x E

X)

(constructed

in

the

above

two theorems) which are indexed by

all

subsets

A

~

X whose

cardinality

is a

power

of

2, one considers

their

projections in a O((log n)2)-dimensional subspace.

10.1

Embeddings

with

Distortion

129

Namely, for each

cardinality

s

:::::

IXI

= n which is a power

of

2 one

randomly

chooses O(log n)

subsets

A

~

X

of

cardinality

s;

then,

one

restricts

the

coor-

dinates

of

Ux,V

x

to

be

indexed

by these

O((logn?)

subsets

of

X.

Moreover,

if

1

:::::

p

:::::

2, every

semimetric

on

n

points

can

be

embedded

into

f~(logn)

with

distortion

O(logn);

this

is shown

in

Linial,

London

and

Rabinovich

[1994], using

earlier

results

by

Johnson

and

Lindenstrauss

[1984]

and

Bourgain

[1985].

Such

embed

dings

can

be

constructed

in

random

polynomial

time.

For a

semimetric

d

on

n

points,

let

C(d)

denote

the

smallest

distortion

with

which d

can

be

em-

bedded

into

some f

2

-space. We will see below (see

Proposition

10.2.1

and

the

remarks

thereafter)

that,

for every E >

0,

one

can

find

in

polynomial

time

an

embedding

of

d

into

f~

with

distortion

C(d)

+ E.

The

following

result

is a

variant

of

Theorem

10.1.2

due

to

Linial,

London

and

Rabinovich

[1994],

that

we will use

later

in

this

section for

approximating

multicommodity

flows.

Theorem

10.1.6.

Let

(X,

d)

be

a finite

semimetric

space and let Y

~

X with

k

:=

WI.

There exist vectors

Wx

E

~K

(x

E

X)

satisfying

II

Wx

-Wy

IiI:::::

d(x,y)

d(x,

y)

:::::

Co

log2(k)

II

WX

-

Wy

111

for all

x,y

EX,

for

all

x,

y E Y.

Here, K =

2:~~~2

kJ

(2~)

(<

2k)

and

Co

> 0 is a constant.

Proof.

The

proof

is analogous

to

that

of

Theorem

10.1.2

but,

now, we

construct

a

Lipschitz

f

1

-embedding

using only

subsets

of

Y.

Namely, we define

Wx

E

~K

by

setting

Then,

II

WX

-

Wy

Ill:::::

d(x,y)

holds for all

x,y

E

X.

Moreover, by

the

proof

of

Theorem

10.1.2,

the

relation:

d(x,

y)

:::::

Co

log2

k

II

WX

-

Wy

111

holds for all

x,y

E

Y.

I

In

fact, for

the

purpose

of

finding

good

approximations

in

polynomial

time

for

multicommodity

flows, we will need

the

following

strengthening

of

Theo-

rem

10.1.6, whose

proof

can

be

found

in

Linial,

London

and

Rabinovich

[1994].

Theorem

10.1.7.

Let

(X,

d)

be

a finite

semimetric

space

and

let Y

~

X with

k

:=

WI.

There exist vectors

Wx

E

~O(n2)

(x

E

X)

satisfying

II

Wx

-

Wy

Ill:::::

d(x,y)

d(x,y)::::: colog2(k)

II

Wx

-Wy

111

for

all

x,y

E

X,

for

all

x,y

E Y

(where

Co

> 0 is a constant). Moreover, the vectors

Wx

(x

E

X)

can

be

found

in

polynomial

time.

I

130

Chapter

10. Lipschitz Embeddings

10.2

The

Negative

Type

Condition

for

Lipschitz

Embeddings

Recall from Theorem 6.2.2

that

isometric i2-embeddability

can

be characterized

in

terms

of

the

negative type inequalities.

In

fact, this characterization extends

to Lipschitz i

2

-embeddings, as observed in Linial, London

and

Rabinovich

[1994].

Proposition

10.2.1.

Let C

;::::

1 and let

(X,

d)

be

a finite semimetric space with

X =

{O,

1,

...

,

n}.

The following assertions

are

equivalent.

(i)

(X,

v'd)

has an i2-embedding with distortion C, i.e., there exist

Ui

E

~N

(i

EX)

such that

1 2

(10.2.2)

C2dij

::;

(II

Ui

-

Uj

112)

::;

dij for

i,j

EX.

(ii) There exists a positive semidefinite n x n matrix A

(aij)

satisfying:

{

-bdij::;

G-ii

+

ajj

-

2aij

::;

dij

for 1

::;

i

=I

j

::;

n,

(10.2.3)

-bdOi

::;

ai; ::;

do;

for 1

::;

i

::;

n.

(iii) For every b E

ZX

with L b

i

= 0, d satisfies:

'EX

Before giving

the

proof, let us make some observations. First, note

that

(10.2.4)

in

the

case C 1 is nothing

but

the

usual negative

type

condition.

Hence, (10.2.4) is a generalization of

the

negative type condition for Lipschitz

embeddings. Proposition 10.2.1 has some algorithmic consequences.

In

par-

ticular, one can evaluate in polynomial time (with an

arbitrary

precision)

the

smallest distortion C*

with

which

(X,

v'd)

can

be embedded into

an

i2-space.

Indeed,

C* where

>.'

max

A

Ad'j

::;

au

+

ajj

-

2a'j

::;

d

ij

Adoi ::; ai;

::;

do.

AtO

A

;::::

O.

(l::;i=lj::;n)

(i=l,

...

,n)

This

optimization program can

be

solved using, for instance,

the

ellipsoid algo-

rithm

(cf.

Grotschel, Lovasz

and

Schrijver [1988]).

By

the

results mentioned

earlier,

C*

O(logn).

10.2

The

Negative

Type

Condition for Lipschitz Embeddings

131

Proof

of

Proposition 10.2.1.

We

set

Vn

X \

{O}

{I,

...

,n}.

(i)

==?

(ii)

We

can suppose without loss of generality

that

Uo

O.

Set a,]

:=

u;

u

J

for all

i,j

E V

n

.

Then,

the

matrix

(a'j) satisfies (ii).

(ii)

==?

(i) As A is positive semidefinite,

it

is

the

Gram

matrix

of some vectors

Ul,

...

,Un'

Then,

the

vectors

Uo

0,

Ul,

..

,

Un

satisfy (10.2.2).

(ii)

==?

(iii) Let A be a matrix satisfying (ii).

We

construct a distance D on

X by setting Do.

a"

for i E

Vn

and

Dij

:=

ai;

+

ajj

2aij for i

:f:.

j E V

n

.

Then,

D is

of

negative type as A is positive semidefinite. Hence, given b E

ZX

with b

i

0, we have: bibjDij

;:;

O.

By assumption (ii), bibjDii

::::

-bbibjdij if bibj >

0,

and bibjDij

::::

bibjdij if bibj <

O.

This shows

that

(10.2.4)

holds.

(iii)

(ii)

We

suppose

that

(iii) holds. This implies

that,

for every positive

semidefinite

matrix

B

(bij

)i,jEX

such

that

Be

= 0

(e

denoting

the

all-ones

vector),

(10.2.5)

1

Let us suppose

that

(ii) does not hold. Then,

the

two cones

PSD

n

(the

cone of

positive semidefinite

n x n matrices) and K

:=

{A

=

(aij)

I A satisfies (10.2.3)}

are disjoint. Therefore, there exists a hyperplane separating PSD

n

and

K.

In

other

words, there exists a symmetric

matrix

Z and a scalar

GO

satisfying:

(Z, A) >

GO

for all A E

PSD

n

and (A, Z)

;:;

GO

for all A E

K,

where

(Z,A):=

L

Zijaij·

l:";i,j:";n

Hence,

GO

<

0,

which implies

that

Z is positive semidefinite. Moreover, as

the

inequality (Z, A)

;:;

GO

is valid for the cone

K,

it

can be expressed as a nonnegative

linear combination

of

the

inequalities defining

K.

Therefore, there exist two

symmetric matrices

(Aij)

and (/-Lij) with nonnegative entries such

that

(Z,"4) = L

(Aij

-

/-Lij)(aii

+

ajj

-

2aij)

+ L (Ai' /-Lii)aii

ihEV"

iEV"

for all A,

and

(10.2.6)

We

define the symmetric

matrix

B indexed by X by

boo:= L

Ajj

/-Ljj,

bi,

JEV"

bOi

:=

-Ai,

+

/-Lii

for i E V

n

,

b

ij

:=

-Aij

+

/-Lij

for i

:f:.

j E V

n

.

132

Chapter

10.

Lipschitz Embeddings

By construction,

Be

= 0 and B is positive semidefinite (as L bijaij = (Z,

A)

2:

o for all A E PSDn). Observe now

that,

as C

2:

1,

.

(b

bij ) > /lij \ ( . .../..

v.)

.

(b

mm

ij,

C2

~

C2

~

Aij

~

r J

En,

mm

Oi,

These relations together with (10.2.6) yield:

which contradicts

the

assumption (10.2.5).

>

/li;

\ ( . T.')

~

C2

~

Aii

2 E

Yn

•

I

10.3

An

Application

for

Approximating

Multicom-

modity

Flows

We

present here

an

application

of

the above results on Lipschitz l\-embeddings

with

distortion to the approximation

of

multicommodity

flows.

We

start

with

recalling several definitions. Let G =

(yr,

E)

be a connected

graph

and

let

(Sb

t

l

),

...

, (Sk' tk) be k distinct pairs

of

nodes

in

yr,

called

terminal

pairs (or commodity pairs).

We

are given for each edge e E E a number E

called

the

capacity of the edge e and, for each terminal pair (Sh' th), a number

Dh

2:

0 called its demand. For h =

1,

...

, k, let Ph denote

the

set

of

paths

joining

the terminals

Sh

and th

in

G; set

P:=

U Ph·

l~h~k

A

multicommodity

flow is a function f : P

--+

lll4.

The

multicommodity

flow

f

is said to

be

feasible for

the

instance (G, C,

D)

if

it

satisfies

the

following capacity

and

demand

constraints:

L

fp:$

C

e

for all e E

E,

for h =

1,

...

,k.

A classical problem

in

the

theory

of

networks is to find a feasible multicommodity

flow

(possibly satisfying some further cost constraints).

We

are interested here

in

the

following variant of the problem, known as the concurrent flow problem:

Determine

the largest scalar

,x*

for which there exists a feasible mul-

ticommodity flow

for

the instance (G,

C,,x*

D).

So,

in

this problem, one tries to satisfy the largest possible fraction ,xDh of

demand

for each terminal pair (Sh' th), while respecting the capacity constraints.

10.3

An

Application for

Approximating

Multicommodity

Flows

133

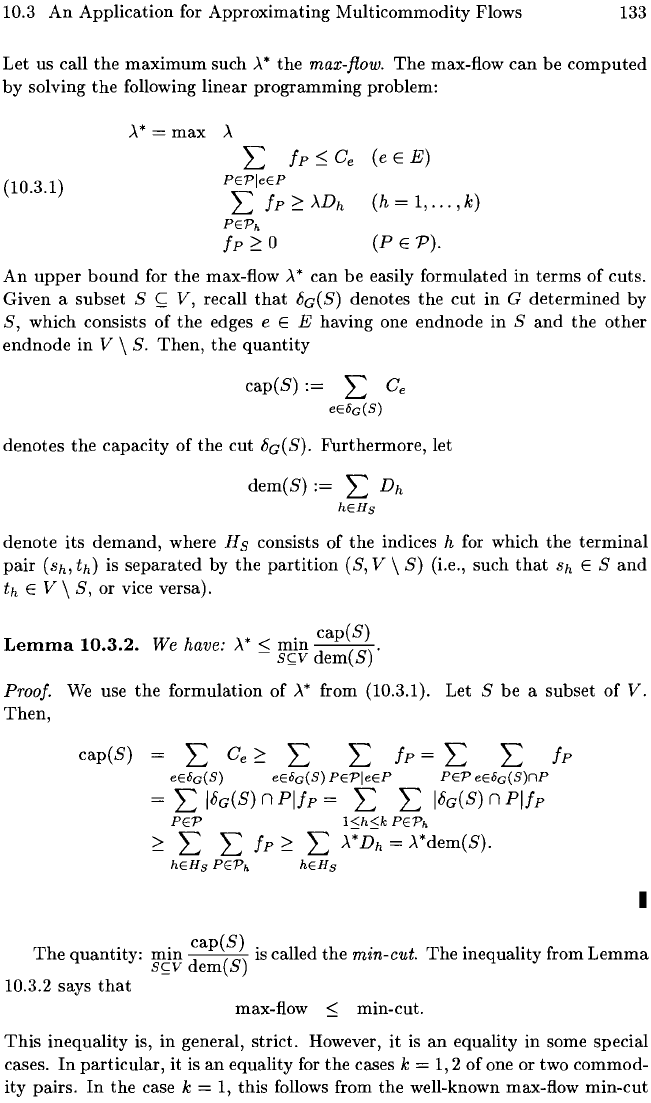

Let

us call

the

maximum

such

A*

the

max-flow.

The

max-flow

can

be

computed

by

solving

the

following linear

programming

problem:

A*

=

max

A

2:

fp

'5:.

C

e

(e

E E)

(10.3.1)

PEPleEP

2:

fp?

ADh

(h

= 1,

...

,k)

(P E P).

An

upper

bound

for

the

max-flow

A*

can

be

easily formulated

in

terms

of

cuts.

Given a

subset

S

<;;:

V, recall

that

oG(S)

denotes

the

cut

in

G

determined

by

S,

which consists

of

the

edges e E E having one

endnode

in

S

and

the

other

endnode

in

V \ S.

Then,

the

quantity

cap(S):=

2:

C

e

eEOa(S)

denotes

the

capacity

of

the

cut

OG(S),

Furthermore,

let

dem(S):=

2:

Dh

hEHs

denote

its

demand,

where

Hs

consists of

the

indices h for which

the

terminal

pair

(Sh'

th)

is

separated

by

the

partition

(S, V \ S) (i.e., such

that

Sh

E

Sand

th

E V \

S,

or vice versa).

* .

cap(S)

Lemma

10.3.2.

We have: A

'5:.

mm

-(S)'

s~v

dem

Proof. We use

the

formulation

of

A*

from (10.3.1). Let S

be

a subset

of

V.

Then,

cap(S)

2:

C

e

?

2: 2:

fp

=

2: 2:

fp

eEOa(S) eEOa(S)

PEPleEP

PEP

eEOa(S)np

=

2:

IOG(S)

n

Plfp

=

2: 2:

IOG(S)

n

Plfp

PEP

l<h<k

PEPh

?

2: 2:

fp?

2:

A;Dh

= A*dem(S).

hEHs

PEPh

hEHs

I

The

quantity:

min

dcap((Ss))

is

called

the

min-cut.

The

inequality from

Lemma

s~v

em

10.3.2 says

that

max-flow

'5:.

min-cut.

This

inequality is,

in

general,

strict.

However,

it

is

an

equality

in

some special

cases.

In

particular,

it is

an

equality for

the

cases k =

1,2

of

one or two commod-

ity

pairs.

In

the

case k =

1,

this follows from

the

well-known max-flow

min-cut