Desurvire E. Classical and Quantum Information Theory: An Introduction for the Telecom Scientist

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4.3 Language entropy 57

4.3 Language entropy

Here, we shall see how Shannon’s entropy can be applied to analyze languages,as

primary sources of word symbols, and to make interesting comparisons between different

types of language.

As opposed to dialects, human languages through history have always possessed some

written counterparts. Most of these language “scripts” are based on a unique, finite-size

alphabet of symbols, which one has been trained in early age to recognize and manipulate

(and sometimes to learn later the hard way!).

7

Here, I will conventionally call symbols

“characters,” and their event set the “alphabet.” This is not to be confused with the

“language source,” which represents the set of all words that can be constructed from

said alphabet. As experienced right from early school, not all characters and words are

born equal. Some characters and words are more likely to be used; some are more rarely

seen. In European tongues, the use of characters such as X or Z is relatively seldom,

while A or E are comparatively more frequent, a fact that we will analyze further down.

However, the statistics of characters and words are also pretty much context-

dependent. Indeed, it is clear that a political speech, a financial report, a mortgage

contract, an inventory of botanical species, a thesis on biochemistry, or a submarine’s

operating manual (etc.), may exhibit statistics quite different from ordinary texts! This

observation does not diminish the fact that, within a language source, (the set of all

possible words, or character arrangements therein), words and characters are not all

treated equal. To reach the fundamentals through a high-level analysis of language, let

us consider just the basic character statistics.

A first observation is that in any language, the probability distribution of characters

(PDF), as based on any literature survey, is not strictly unique. Indeed, the PDF depends

not only on the type of literature surveyed (e.g., newspapers, novels, dictionaries, tech-

nical reports) but also on the contextual epoch. Additionally, in any given language

practiced worldwide, one may expect significant qualitative differences. The Continen-

tal and North-American variations of English, or the French used in Belgium, Quebec,

or Africa, are not strictly the same, owing to the rich variety of local words, expressions,

idioms, and literature.

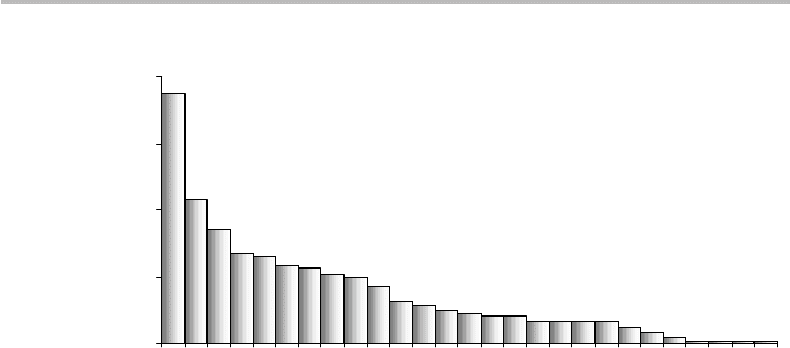

A possible PDF for English alphabetical characters, which was realized in 1942,

8

is

shown in Fig. 4.2. We first observe from the figure that the discrete PDF nearly obeys an

exponential law. As expected, the space character (sp) is the most frequent (18.7%). It is

followed by the letters E, T, A, O, and N, whose occurrence probabilities decrease from

10.7% and 5.8%. The entropy calculation for this source is H = 4.065 bit/symbol. If we

remove the most likely occurring space character (whose frequency is not meaningful)

from the source alphabet, the entropy increases to H = 4.140 bit/symbol.

7

The “alphabet” of symbols, as meaning here the list of distinct ways of forming characters, or voice sounds,

or word prefixes, roots, and suffixes, or even full words, may yet be quite large, as the phenomenally rich

Chinese and Japanese languages illustrate.

8

F. Pratt, Secret and Urgent (Indianapolis: The Bobbs-Merrill Book Company, 1942). Cited in J. C. Hancock,

An Introduction to the Principles of Communication Theory (New York: McGraw Hill, 1961).

58 Entropy

0

5

10

15

20

spET AONRI S HDLF CMUGYPWBVKX JQZ

Probability (%)

Figure 4.2 Probability distribution of English alphabetical characters, as inventoried in 1942.

The source entropy with or without the space character is H = 4.065 bit/symbol and

H = 4.140 bit/symbol, respectively.

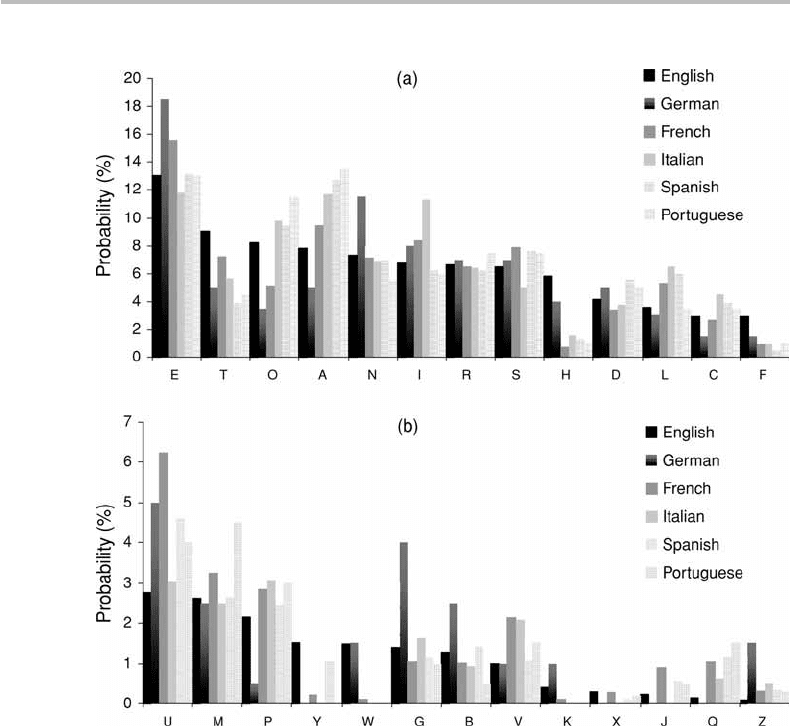

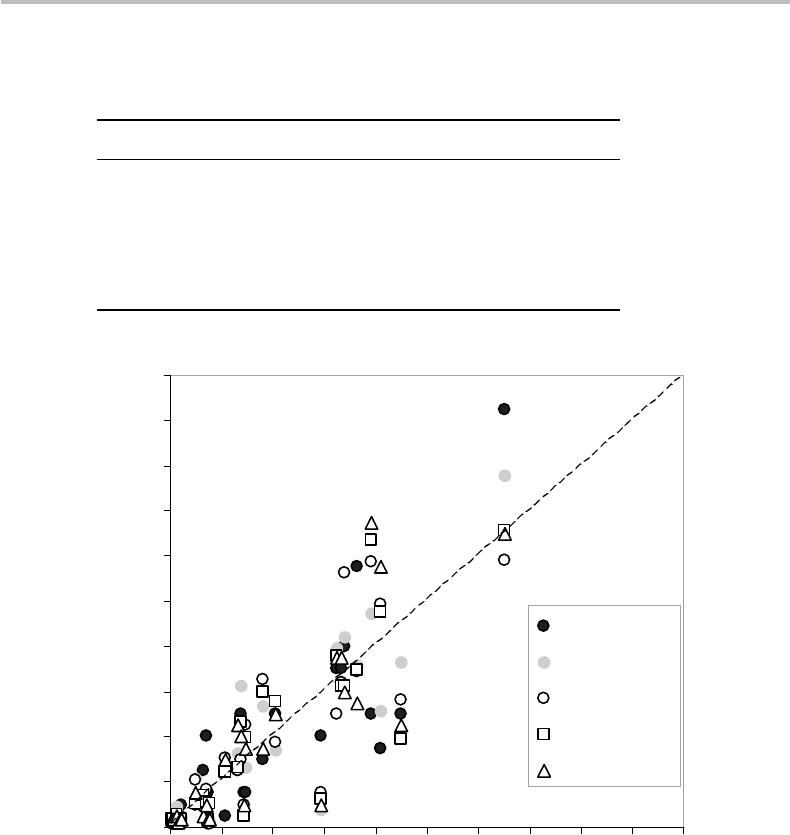

Figure 4.3 shows the probability distributions for English, German, French, Italian,

Spanish, and Portuguese, after inventories realized in 1956 or earlier.

9

For comparison

purposes, the data were plotted in the decreasing-probability sequence corresponding

to English (Fig. 4.2). We observe that the various distributions exhibit a fair amount of

mutual correlation, together or by subgroups. Such a correlation is more apparent if we

plot in ordinates the different symbol probabilities against the English data, as shown in

Fig. 4.4. The two conclusions are:

(a) Languages make uneven use of symbol characters (corresponding to discrete-

exponential PDF);

(b) The PDFs are unique to each language, albeit showing a certain degree of mutual

correlation.

Consider next language entropy. The source entropies, as calculated from the data in

Fig. 4.3, together with the 10 most frequent characters, are listed in Table 4.2.The

English source is seen to have the highest entropy (4.147 bit/symbol), and the Italian one

the lowest (3.984 bit/symbol), corresponding to a small difference of 0.16 bit/symbol.

A higher entropy corresponds to a fuller use of the alphabet “spectrum,” which creates

more uncertainty among the different symbols. Referring back to Fig. 4.3, we observe

that compared with the other languages, English is richer in H, F, and Y, while German

is richer in E, N, G, B, and Z, which can intuitively explain that their source entropies are

the highest. Compared with the earlier survey of 1942, which gave H(1942) =4.140 bit/

symbol, this new survey gives H (1956) = 4.147 bit/symbol. This difference is not really

meaningful, especially because we do not have a basis for comparison between the

type and magnitude of the two samples that were used. We can merely infer that the

introduction of new words or neologisms, especially technical neologisms, contribute

9

H. Fouch

´

e-Gaines, Cryptanalysis, a study of ciphers and their solutions (New York: Dover Publications,

1956).

4.3 Language entropy 59

Figure 4.3 Probability distributions of character symbols for English, German, French, Italian,

Spanish and Portuguese, as inventoried in 1956 or earlier and as ordered according to English.

The corresponding source entropy and 10 most frequent letters are shown in Table 4.2.

over the years to increase entropy. Note that the abandonment of old-fashioned words

does not necessarily counterbalance this effect. Indeed, the old words are most likely to

have a “classical” alphabet structure, while the new ones are more likely to be unusual,

bringing a flurry of new symbol-character patterns, which mix roots from different

languages and technical jargon.

What does an entropy ranging from H =3.991 to 4.147 bit/symbol actually mean for

any language? We must compare this result with an absolute reference. Assume, for the

time being, that the reference is provided by the maximum source entropy, which one can

get from a uniformly distributed source. The maximum entropy of a 26-character source,

which cannot be surpassed, is thus H

max

= I (1/26) = log 26 = 4.700 bit/symbol. We

see from the result that our European languages are not too far from the maximum

entropy limit, namely, within 85% to 88% of this absolute reference. As described in

forthcoming chapters, there exist different possibilities of coding language alphabets

60 Entropy

Table 4.2 Alphabetical source entropies H of English, German, French, Italian,

Spanish, and Portuguese, and the corresponding ten most frequent characters.

H (bit/symbol) Ten most frequent characters

English 4.147 E T O A N I R S H D

German 4.030 E N I R S T A D U H

French 4.046 E A I S T N R U L O

Italian 3.984 E A I O N L R T S C

Spanish 4.038 E A O S N I R L D U

Portuguese 3.991 A E O S R I N D T M

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

16

18

20

02468101214161820

English symbol-character probability (%)

Other language symbol-character probability (%)

German

French

Italian

Spanish

Portuguese

Figure 4.4 Correlation between English character symbols with that of other European

languages, according to data shown in Fig. 4.3.

with more compact symbols, or codewords, in such a way that the coded language

source may approach this entropy limit.

Table 4.2 also reveals that there exist substantial differences between the ten most

frequent symbol characters. Note that this (1956) survey yields for English the sequence

ETOANIRSHD, while the earlier data (1941) shown in Fig. 4.2 yields the sequence

ETAONRISHD. This discrepancy is, however, not significant considering that the prob-

ability differences between A and O and between R and I are between 0.1% and 0.4%,

which can be considered as an effect of statistical noise. The most interesting side of

4.3 Language entropy 61

these character hierarchies is that they can provide information as to which language is

used in a given document, in particular if the document has been encrypted according to

certain coding rules (this is referred to as a ciphertext). The task of decryption, recover-

ing what is referred to as the plaintext, is facilitated by the analysis of the frequencies (or

probabilities) at which certain coded symbols or groups of coded symbols are observed

to appear.

10

To illustrate the effectiveness of frequency analysis, let us perform a basic

experiment. The following paragraph, which includes 1004 alphabetic characters, has

been written without any preparation, or concern for contextual meaning (the reader

may just skip it):

During last winter, the weather has been unusually cold, with records in temperatures, rainfalls

and snow levels throughout the country. According to national meteorology data, such extreme

conditions have not been observed since at least two centuries. In some areas, the populations of

entire towns and counties have been obliged to stay confined into their homes, being unable to take

their cars even to the nearest train station, and in some case, to the nearest food and utility stores.

The persistent ice formation and accumulation due to the strong winds caused power and telephone

wires to break in many regions, particularly the mountain ones of more difficult road access. Such

incidents could not be rapidly repaired, not only because these adverse conditions settled without

showing any sign of improvement, but also because of the shortage of local intervention teams,

which were generally overwhelmed by basic maintenance and security tasks, and in some case

because of the lack of repair equipment or adequate training. The combined effects of fog, snow

and icing hazards in airports have also caused a majority of them to shut down all domestic

traffic without advanced notice. According to all expectations, the President declared the status of

national emergency, involving the full mobilization of police and army forces.

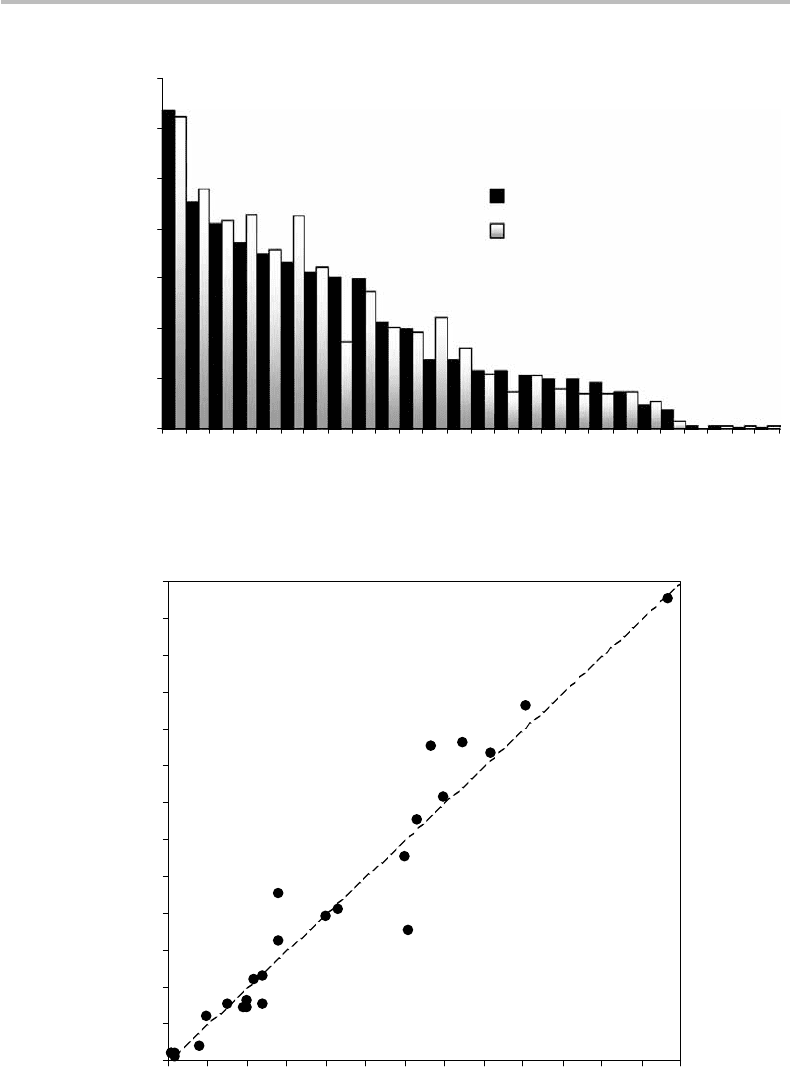

A rapid character count of the above paragraph (with a home computer

11

) provides the

corresponding probability distribution. For comparison purposes, we shall use this time

an English-language probability distribution based on a more recent (1982) survey.

12

This survey was based on an analysis of newspapers and novels with a total sample

of 100 362 alphabetic characters. The results are shown in Figs. 4.5 and 4.6 for the

distribution plot and the correlation plot, respectively. We observe from these two plots a

remarkable resemblance between the two distributions and a strong correlation between

them.

13

This result indicates that any large and random sample of English text, provided

it does not include specialized words or acronyms, closely complies with the symbol-

distribution statistics. Such compliance is not as surprising as the fact that it is so good

considering the relatively limited size of the sample paragraph.

10

It is noteworthy that frequency analysis was invented as early as the ninth century, by an Arab scientist and

linguist, Al-Kindi.

11

This experiment is easy to perform with a home computer. First write or copy and paste a paragraph on

any subject, which should include at least N =1000 alphabetical characters. Then use the find and replace

command to substitute letter A with a blank, and so on until Z. Each time, the computer will indicate how

many substitutions were effected, which directly provides the corresponding letter count. The data can then

be tabulated at each step and the character counts changed into probabilities by dividing them by N.The

whole measurement and tabulating operation should take less than ten minutes.

12

S. Singh, The Code Book: The Science of Secrecy from Ancient Egypt to Quantum Cryptography (New

York: Anchor Books, 1999).

13

The reader may trust that this was a single-shot experiment, the plots being realized after having written

the sample paragraph, with no attempt to modify it retroactively in view of improving the agreement.

62 Entropy

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

14

ETAOI NS HRDLCUMWFGYPBVKJXQZ

Symbol-character probability (%)

English reference

Sample paragraph

Figure 4.5 Probability distributions of symbol-characters used in English reference (as per a

1982 survey) and as computed from the author’s sample paragraph shown in the text.

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13

English-symbol reference probability (%)

Sample-symbol probability (%)

Figure 4.6 Correlation between English reference and author’s sample probability distributions.

4.4 Maximum entropy (discrete source) 63

As an interesting feature, the entropy of the 1982 English symbol-character source

is computed as H(1982) = 4.185 bit/symbol.

14

This is larger than the 1956 data

(H (1956) = 4.147 bit/symbol) and the 1942 data (H(1942) = 4.140 bit/symbol). If

we were to attribute equal reference value to these data, a rapid calculation shows that

the English source entropy grew by 0.17% in 1942–1956, and by approximately 0.9% in

1956–1982. This growth also corresponds to 1.1% over 40 years, which can be linearly

extrapolated to 2.75% in a century, say a growth rate of 3%/century. Applying this rate up

to the year of this book writing (2005), the entropy should be at least H (2005) =4.20 bit/

symbol. One century later (2105), it should be at least H (2105) = 4.32 bit/symbol. In

reference to the absolute A–Z source limit (H

max

= 4.700 bit/symbol), this would rep-

resent an efficiency of alphabet use of H(2105)/H

max

= 92%, to compare with today’s

efficiency, i.e., H (2005)/H

max

= 89%. We can only speculate that a 100% efficiency

may never be reached by any language unless cultural influence and mixing makes it

eventually lose its peculiar linguistic and root structures.

4.4 Maximum entropy (discrete source)

We have seen that the information related to any event x having probability p(x) is defined

as I (x) =−log p(x). Thus, information increases as the probability decreases or as the

event becomes less likely. The information eventually becomes infinite (I (x) →∞)in

the limit where the event becomes “impossible” ( p(x) → 0). Let y be the complementary

event of x, with probability p(y) = 1 − p(x). In the previous limit, the event y becomes

“absolutely certain” ( p(y) → 1), and consistently, its information vanishes (I (y) =

−log p(y) → 0).

The above shows that information is unbounded, but its infinite limit is reached only for

impossible events that cannot be observed. What about entropy? We know that entropy is

the measure of the average information concerning a set of events (or a system described

by these events). Is this average information bounded? Can it be maximized, and to

which event would the maximum correspond?

To answer these questions, I shall proceed from the simple to the general, then to the

more complex. I consider first a system with two events, then with k events, then with

an infinite number of discrete events. Finally, I introduce some constraints in the entropy

maximization problem.

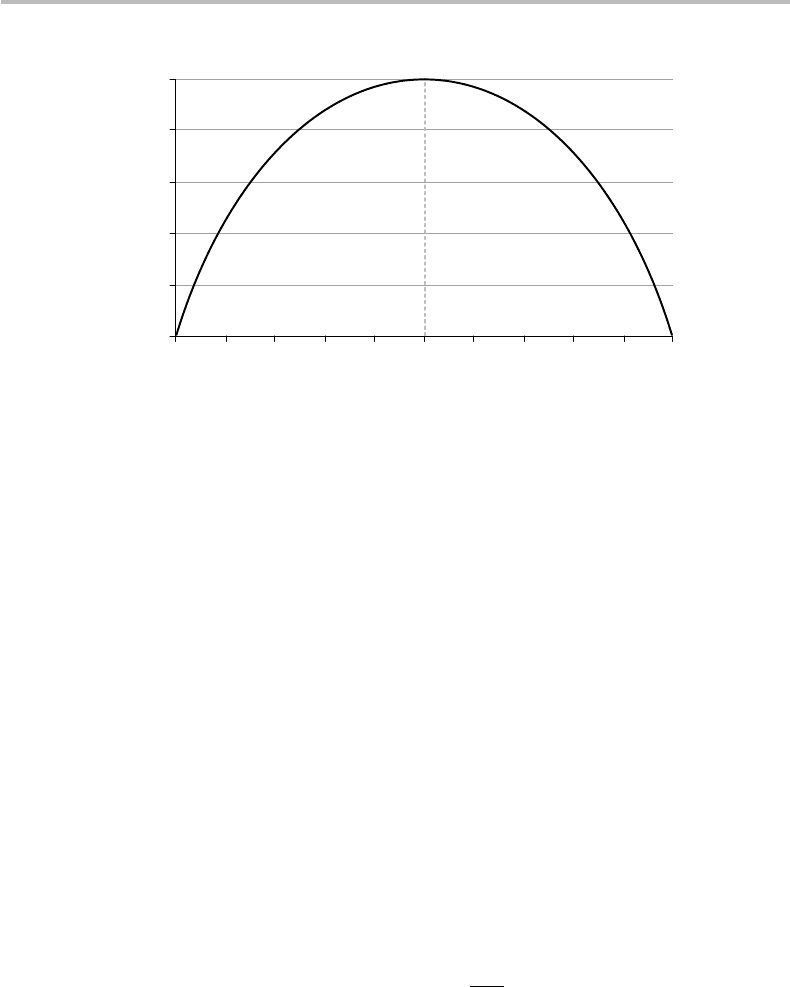

Assume first two complementary events x

1

, x

2

with probabilities p(x

1

) = q and

p(x

2

) = 1 −q, respectively. By definition, the entropy of the source X ={x

1

, x

2

} is

given by

H(X ) =−

x∈X

p(x)log p(x)

=−x

1

log p(x

1

) − x

2

log p(x

2

) (4.13)

=−q log q − (1 −q)log(1− q) ≡ f (q).

14

The entropy of the sample paragraph is H =4.137 bit/symbol, which indicates that the sample is reasonably

close to the reference (H (1982) = 4.185 bit/symbol), meaning that there is no parasitic effect due to the

author’s choice of the subject or his own use of words.

64 Entropy

Note the introduction of the function f (q):

f (q) =−q log q − (1 −q)log(1− q) ≡ f (q), (4.14)

which will be used several times through these chapters.

A first observation from the definition of H (X) = f (q) is that if one of the two

events becomes “impossible,” i.e., q = ε → 0or1− q = ε → 0, the entropy remains

bounded. Indeed, the corresponding term vanishes, since ε log ε → 0 when ε → 0. In

such a limit, however, the other term corresponding to the complementary event, which

becomes “absolutely certain,” also vanishes (since u log u → 0 when u → 1). Thus, in

this limit the entropy also vanishes, or H (X ) → 0, meaning that the source’s information

is identical to zero as a statistical average. This situation of zero entropy corresponds to a

fictitious system, which would be frozen in a state of either “impossibility” or “absolute

certainty.”

We assume next that the two events are equiprobable, i.e., q = 1/2. We then obtain

from Eq. (4.13):

H(X ) = f

1

2

=−

1

2

log

1

2

−

1 −

1

2

log

1 −

1

2

=−log

1

2

= 1. (4.15)

The result is that the source’s average information (its entropy) is exactly one bit.This

means that it takes a single bit to define the system: either event x

1

or event x

2

is observed,

with equal likelihood. The source information is, thus, given by a simple YES/NO

answer, which requires a single bit to formulate. In conditions of equiprobability, the

uncertainty is evenly distributed between the two events. Such an observation intuitively

conveys the sense that the entropy is a maximum in this case. We can immediately verify

this by plotting the function H(X ) ≡ f (q) =−q log q − (1 −q)log(1− q) defined in

Eq. (4.14), from q = 0(x

1

impossible) to q = 1(x

1

absolutely certain). The plot is shown

in Fig. 4.7. As expected, the maximum entropy H

max

= 1 bit is reached for q = 1/2,

corresponding to the case of equiprobable events.

Formally, the property of entropy maximization can be proved by taking the derivative

dH/dq and finding the root, i.e., dH/dq = log[(1 −q)/q] = 0, which yields q = 1/2.

We now extend the demonstration to the case of a source with k discrete events,

X ={x

1

, x

2

,...,x

k

} with associated probabilities p(x

1

), p(x

2

),..., p(x

k

). This is a

problem of multidimensional optimization, which requires advanced analytical methods

(here, namely, the Lagrange multipliers method).

The solution is demonstrated in Appendix C. As expected, the entropy is maximum

when all the k source events are equiprobable, i.e., p(x

1

) = p(x

2

) =···= p(x

k

) = 1/k,

which yields H

max

= log k. If we assume that k is a power of two, i.e., k = 2

M

, then

H

max

= log 2

M

= M bits. For instance, a source of 2

10

= 1024 equiprobable events has

an entropy of H = 10 bits.

The rest of this chapter, and Appendix C, concerns the issue of PDF optimization for

entropy maximization, under parameter constraints. This topic is a bit more advanced

than the preceding material. It may be skipped, without compromising the understanding

of the following chapters.

4.4 Maximum entropy (discrete source) 65

0

0.2

0.4

0.6

0.8

1

0 0.1 0.2 0.3 0.4 0.5 0.6 0.7 0.8 0.9 1

Probability

q

Entropy

H(q),

bit

Figure 4.7 Plot of the entropy H (X ) = f (q) for a source with two complementary events with

probabilities q and 1 −q (Eq. (4.14)), showing maximum point H

max

= H (0.5) = 1where

events are equiprobable.

In Appendix C, I also analyze the problem of entropy maximization through PDF

optimization with the introduction of constraints.

A first type of constraint is to require that the PDF have a predefined mean value

x=N . In this case, the following conclusions can be reached:

r

If the event space X ={x

1

, x

2

,...,x

k

} is the infinite set of integer numbers

(x

1

= 0, x

2

= 1, x

3

= 2 ...), k →∞, the optimal PDF is the discrete-exponential

distribution, also called the Bose–Einstein distribution (see Chapter 1);

r

If the event space X ={x

1

, x

2

,...,x

k

} is a finite set of nonnegative real numbers, the

optimal PDF is the (continuous) Boltzmann distribution.

The Bose–Einstein distribution characterizes chaotic processes, such as the emission of

light photons by thermal sources (e.g., candle, light bulb, Sun, star) or the spontaneous

emission of photons in laser media. The Boltzmann distribution describes the random

arrangement of electrons in discrete atomic energy levels, when the atomic systems are

observed at thermal equilibrium.

As shown in Appendix C, the (maximum) entropy corresponding to the Boltzmann

distribution, as defined in nats,is:

H

max

=m

hν

k

B

T

, (4.16)

where hν is the quantum of light energy (photon), k

B

T is the quantum of thermal

energy (phonon) and m is the mean number of phonons at absolute temperature T

and oscillation frequency ν (h = Planck’s constant, k

B

= Boltzmann’s constant). The

quantity E =mhν is, thus, the mean electromagnetic energy or heat that can be

radiated by the atomic system. The ratio E/(k

B

T ) is the number of phonons required

to keep the system in such a state. The maximal entropy H

max

, which represents the

average information to define the system, is just equal to this simple ratio! This feature

66 Entropy

establishes a nice connection between information theory and atomic physics. Letting

S = k

B

H

max

, which is consistent with the physics definition of entropy, we note that

S = E/T , which corresponds to the well known Clausius relation between system

entropy (S), heat contents (E), and absolute temperature (T ).

15

Consider next the possibility of imposing an arbitrary number of constraints on the

probability distribution function (PDF) moments, x, x

2

,...,x

n

.

16

The general PDF

solution for which entropy is maximized takes the nice analytical form (Appendix C):

p

j

= exp

λ

0

− 1 +λ

1

x

j

+ λ

2

x

2

j

+···+λ

n

x

n

j

, (4.17)

where λ

0

,λ

1

,λ

2

,...,λ

n

are the Lagrange multipliers, which must be computed numeri-

cally. The corresponding (maximum) entropy is simply given by:

H

max

= 1 −

λ

0

+ λ

1

x+λ

2

x

2

+···+λ

n

x

n

= 1 −

n

i=0

λ

i

x

i

. (4.18)

Maximization of entropy is not limited to constraining PDF moments. Indeed, any set

of known functions g

k

(x) and their mean g

k

(k = 1,...,n) can be used to define and

impose as many constraints. It is easily established that, in this case, the optimal PDF

and maximum entropy takes the form:

p

j

= exp[−1 + λ

0

g

0

(x

j

) + λ

1

g

1

(x

j

) +···+λ

n

g

n

(x

j

)], (4.19)

H

max

= 1 −

n

i=0

λ

i

g

i

. (4.20)

From the observation in the real world of the functions or parameters g

k

(x), g

k

,itis

thus possible heuristically to infer a PDF that best models reality (maximum entropy

at macroscopic scale), assuming that a large number of independent microstates govern

the process. This is discussed later.

Entropy maximization leads to numerically defined PDF solutions, which are essen-

tially nonphysical. Searching for such solutions, however, is not a matter of pure academic

interest. It can lead to new insights as to how the physical reality tends to exist in states

of maximum entropy.

For instance, I showed in previous work

17

that given constraints in x,σ

2

=x

2

−

x, the entropy of amplified coherent light is fairly close to that of the optimal-numerical

PDF giving maximal entropy. For increasing photon numbers x, the physical photon-

statistics PDF and the optimal-numerical PDF are observed to converge asymptotically

towards the same Gaussian distribution, as a consequence of the central-limit theorem

(Chapter 1).

15

It is beyond the scope of these chapters to discuss the parallels between entropy in Shannon’s information-

theory and entropy in physics. Further and accessible considerations concerning this (however com-

plex) subject can be found, for instance, in: www.tim-thompson.com/entropy1.html, www.panspermia.

org/seconlaw.htm, http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Entropy.

16

A moment of order k is, by definition, the mean value of x

k

, namely, x

k

=

x

k

i

p

i

.

17

E. Desurvire, How close to maximum entropy is amplified coherent light? Opt. Fiber Technol., 6 (2000),

357. See also, E. Desurvire, D. Bayart, B. Desthieux, and S. Bigo, Erbium-Doped Fiber Amplifiers: Device

and System Developments (New York: John Wiley & Sons, 2002), p. 202.