Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Further Reading

Castel, Albert. Ci vil War Kansas: Reaping the Whirlwind. Lawrence: University Press of

Kansas, 1997.

Goodrich, Thomas. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861. Mechanicsburg, PA:

Stackpole Books, 1998.

Starr, Stephen Z. Jennison’s Jayhawkers: A Civil War Cavalry Regiment and Its Com-

mander. Baton Rouge: Louisiana State University Press, 1993.

Missouri Compromise (1820–1821)

The Missouri Compromise was an agreement reached between the pro- and anti-

slavery f actions of the U.S. Congress in 1820 and 1821. It aimed at regulating

slavery in the western territories acquired in the Louisiana Purchase and preserv-

ing the political balance between slave and free states. The debate that led to this

compromise served as an early warning of the potential divisiveness of the slavery

issue and the danger it posed to the Union.

The dispute that ended in the Missouri Compromise began when the territory of

Missouri applied for admission to the Union late in 1818. It was a foregone conclu-

sion that Missouri would enter as a slave state as most of those who had settled the

territory were southerners and many owned slaves. Complicating the question was

Alabama’s admission as a slave state in 1818, ev ening the balance between the slave

and free states. Missouri’s impending statehood raised concerns among antislavery

members of Congress that a new slave state would upset the political balance—par-

ticularly in the U.S. Senate—and lead to slavery’s unfettered expansion.

Feelings in Con gress and the country erupted on February 13, 1819, when, in

response to the Missouri statehood bill brought before the House of Representatives,

New York Congressman James Tallmadge introduced an amendment banning intro-

duction of new slaves into Missouri and providing for the eventual freedom of all

slaves born there. The House members were unprepared for Tallmadge’s action

and, as a result, congressmen on both sides of the slavery question exchanged views

with an intensity and candor previously unseen. An initial House amendment

prohib ited slavery in the fo rme r Louisiana Territo ry except for Missouri, but t he

Senate refused to agree, and the initial effort to reach a compromise collapsed.

The question arose again in the next session of Congress. A new element in the

maneuvering was Maine’s application for admission as a free state. The Senate

decided to link admission of both states. It passed a bill admitting Maine and per-

mitting Missouri to write a state constitution supporting slavery. Congress agreed,

and Maine was admitted on March 3, 1820. This became known as the First

Missouri Compromise.

356 Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858)

The new compromise was threatened when Missouri lawmakers submitted a

constitution prohibiting free blacks from residing in the state. This measure

angered antislavery elements in Congress and raised questions concerning the

citizenship status of free blacks throughout the country. Henry Clay diffused this

second crisis with a proposal that bypassed the question of black citizenship.

Congress accepted Clay’s suggestion along with a ban on slavery in the rest of

the Louisiana Purchase lands—except for Arkansas. On February 26, 1821, Mis-

souri was admitted to the Union as a slave state. This second Missouri Compro-

mise ended the initial slavery crisis.

The Missouri Compromise preserved the political balance between slav e and free

states for the next 30 years. It prohibited the expansion of slavery in practice while

permitting it in principle. The Missouri Compromise, however, failed to address

the underlying differences over the nature of slavery and its meaning for American

democracy. Developments in the 1840s and 1850s—the acquisition of new territo-

ries in the Southwest from Mexico, the organization of the Kansas and Nebraska ter-

ritories, the rise of “popular sovereignty,” and the violence in “Bleeding

Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858) 357

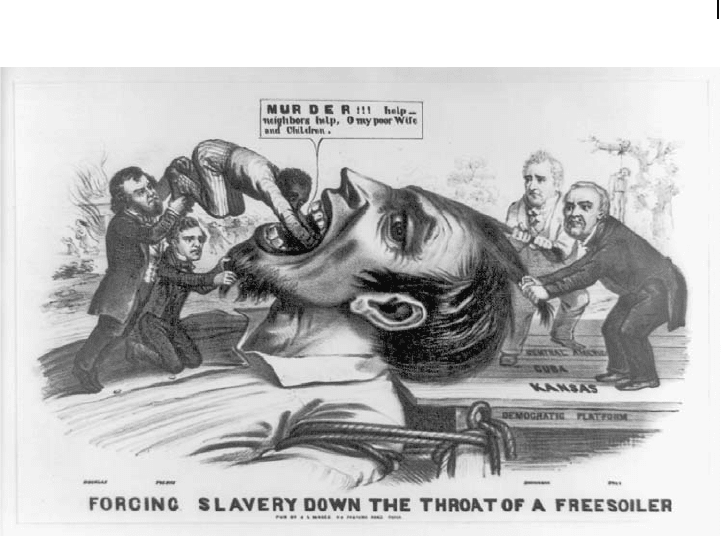

President Franklin Pierce, presidential nominee James Buchanan, Sen. Lewis Cass, and

Sen. Stephen A. Douglas force a man down the throat of a giant in an 1856 political cartoon

satirizing the Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854, which allowed popular sovereignty in regard to

slavery in the two territories. The act nullified the Missouri Compromise of 1820. (Library of

Congress)

Kansas”—led to the unraveling of the Missouri Compromise well before the

Supreme Court declared it unconstitutional in the Dred Scott case in 1859.

—Walter F. Bell

Further Reading

Forbes, Robert Pierce. The Missouri Compromise and Its Aftermath: Slavery a nd the

Meaning of America. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2007.

Popular Sovereignty

Popular sovereignty was a political concept that held that settlers of U.S. territories

were entitled to decide whether they would join the Union as a slave or a free state.

It had particularly strong appeal to Democrats from northwestern states, such as

Senators Lewis Cass of Michigan and Stephen A. Douglas of Illinois. Douglas,

perhaps the dominant Democratic politician of the 1850s, saw popular sovereignty

as a device f or asserting Democrat ic supremacy in the territories and uniting

southern and western Democrats.

In a broad sense, popular sovereignty was the same as local self-government. It

emerged as an issue during the slavery debate in 1848 as a possible solution to the

problem of slavery in the lands acquir ed from Mexico. Popular sovereignty, as

Douglas and other advocates envisioned it, proposed allowing the people settling

any organized territory rather than Congress to determine whether or not to permit

slavery before entering the Union.

Popular sovereignty was mentioned in the Compromise of 1850, which

included admission of California as a free stat e but permitted organization of the

other territories in the Mexican cession with no restrictions on slavery pending a

vote by the settlers in these territories. The Compromise of 1850 strengthened

the determination of the proslavery elements in Congress to assert southern rights

in the organization of any new territories. This stance was to have dire consequen-

ces for the debate on the organization of the Kansas-Nebraska territories, which

arose when a bill for their organization was submitted in 1854. Proslavery legisla-

tors made clear to supporters of the Kansas-Nebraska Bill that they would not

support organization unless their concerns were addressed.

Senator Douglas seized on popular sovereignty as a s olution to the deadlock.

Douglas viewed popular sovereignty as a creed that fit his beliefs in democracy,

local self-governmen t, and expansion based on democratic principles. He had no

reservations about applying popular sovereignty to slavery because he did not con-

sider slavery to be a moral issue. It left open the issue of whether or not North or

358 Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858)

South, slavery or antislavery, would gain in the territories. Douglas considered the

Missouri Compromise of 1820–1821, which banned slavery in the Louisiana Pur-

chase lands north of Missouri, to be out of date.

For their part, southerners found the possibility of introducing slavery in the

Kansas-Nebraska t erritories through popular sovereignty more attractive than an

outright prohibition. Many linked popular sovereignty to a possible repeal of the

Missouri Compromise.

Antislavery northerners, on the other hand, found Douglas’s substitution of popu-

lar sovereignty for a ban on slavery difficult to accept not only because of the threat

it posed to the political balance between slave and free states, but also because they

saw slavery as morally wrong regardless of popular feeling in the territories. Anti-

slavery legislators accused Douglas of breaking faith with the antislavery tradition

of the generation of the American Revolution. In addition, many northern

abolitionist religious leaders considered slavery a violation of the laws of God.

Despite intense opposition, Douglas engineered passage of the Kansas-

Nebraska Act including provisions for det ermining the slave or free status of the

territories through popular vote. He managed this feat with a coalition of southern

Whigs and Democrats. President Pierce signed the Kansas-Nebraska Act into law

on May 29, 1854.

Senator Douglas and the ot her supporters of popular sovereignty saw it as the

ultimate expression of democracy. They failed to comprehend the depth of feeling

in both the pro- and antislavery camps. Douglas’s tragic error was his assumption

that, although the provision for voting on slavery reopened the slavery issue in the

territories, popular sovereignty was sufficiently flexible in its application to silence

any public agitation. He did not understand the divisiveness of the slavery issue or

that neither side would simply accept the popula r will when principles they held

sacred were threatened. The violence surrounding the organization of the Kansas

Territory would expose the shortcomings of popular sovereignty.

—Walter F. Bell

Further Reading

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era.Lawrence:

University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Pottawatomie Massacre (1856)

This incident was a central event in the cycle of political violence between pro-

and antislavery forces in the Kansas Territory, which gave it the name “Bleeding

Kansas.” It occurred on May 24 and 25, 1856, when John Brown and a band of

Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858) 359

abolitionist settlers killed five proslavery men near Pottawatomie Creek in Frank-

lin County near the Kansas-Missouri border.

The massacre was a reprisal for the sacking of Lawrence, Kansas—a stronghold

of antislavery sentiment—on May 21 by a proslavery sheriff’s posse led by Frank-

lin County sheriff Samuel Jones sent by the territorial government to arrest several

antislavery activists. The raid resulted in the destruction of a newspaper office, the

destruction of several private homes, and the burning of a church.

Brown learned of Lawrence’s misfortune on May 23 while camped with a com-

pany of antislavery militia from Osawatomie on patrol near Lawrence. For him

and several of h is followers, the attack on Lawrence was the l ast straw. Brown

led a faction of Free Soilers that advocated violence against proslavery elements.

Their arguments were strengthened by reports of widespread violence against anti-

slavery settlers by “border ruffians” from Missouri and abuses and fraud in the

March 1855 territorial elections that had resulted in the seating of a proslavery

territorial legislature. They were also enraged by news of an attack on abolitionist

senator William Graham Sumner, who was caned nearly to death by South

Carolina congressman Preston Brooks.

Brown was enraged not only by violence against free-state settlers but also by

what he viewed as a coward ly response by leaders of the antislavery faction who

urged their followers to exercise restraint. He regarded them as little more than

cowards and traitors to their cause.

When they heard about the sack of Lawrence, Brown saw an opportunity to put

his advocacy of violence agains t supporters of slavery into action. On May 23,

Brown, along with four of his sons and seven other members of the militia com-

pany, set out on a private retaliatory expedition. They targeted several prominent

proslavery settlers living in the area near Pottawatomie Creek. The most important

among these men was Henry “Dutch Henry” Sherman—a strident proslavery

activist.

Early in the morning of May 24, they reached the house o f James P. Doyle, a

well-known member of the proslavery “Law and Order” Party in Franklin County.

At gun point, they ordered Doyle and his two older sons to come with them as

prisoners. When they had gone some distance from the house, Brown had his

two son s—Owen and Salmon—to kill their prisoners with broadswords. After

watching the hacking to death of their victims, Brown fired a bullet into the senior

Doyle’s head to make sure he was dead.

Brown and his men went further along until they came to the home of ano ther

known proslavery figure, James Wilkinson. There they also discovered James

Sherman, the brother of “Dutch Henry.” Like the Doyles, Wilkinson and Sherman

were killed with broadswords. Unable to find their main target (“Dutch Henry”

Sherm an was away on the prairie), Brown ended the expedition and r eturned to

360 Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858)

the Osawatomie Company on May 25. Shortly thereafter, Brown and his followers

disappeared into the brush country. They were never prosecuted for the massacre,

although Brown was tried and hanged for treason after the Harpers Ferry Raid

in 1859.

The Pottawatomie Massacre sent shockwaves throughout Kansas, Missouri,

and the rest of the country. Far from deterring further attacks, the P ottawatomie

Massacre led to the intensification of guerilla warfare as moderates on both sides

of the slavery dispute found it increasingly difficult to control the extremists. Both

pro- and antislavery militias multiplied and attacked suspected enemies.

Ironically, both sides framed their arguments in terms of democratic values even

as they terrorized their opponents.

—Walter F. Bell

Further Reading

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era.Lawrence:

University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Goodrich, Thoma s. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1988.

Topeka Constitution (1855)

The dispute surrounding the Topeka Constitution is illustrative of the length to

which elements on both sides of the slavery question in the Kansas Territory

would go to get their way on Kansas’s status as slave or free. The Topeka

Constitution was the product of a convention convened by Kansas Free Staters in

Topeka, Kansas, in October 1855. This convention marked the initial effort to

establish a government acceptable to free-state advocates and to get Kansa s

admitted to the Union as a free state. The Topeka Constitution banned slavery in

Kansas.

Free-state advocates had organized the constitutional convention at Topeka to

subvert the creation of the federally sanctioned territorial government and legisla-

ture that had been convened at Pawnee (near present-day Fort Riley) following an

election on March 30, 1855, that had been marre d by widespread violence, voter

intimidatio n, and vote fraud. Free S tater s accused proslavery “bord er ruffians”

from Missouri of crossing into Kansas of crossing into Kansas to stuff ballot boxes

and intimidate Free Soil settlers. Condemnations of the March election intensified

at the Topeka meeting.

Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858) 361

Supporters of the Topeka Constitution were not content to put up an alternative

shadow government. They also moved to elect a state government and submit their

constitution to the U.S. Congress as an application for admission to the Union as a

free state. This was a dangerous move, openly flouting the authority of the legally

constituted territorial legislature and threatening a confrontation with the

administration of President Franklin Pierce.

Despite the dangers, organizers held elections based on the Topeka Constitution

on January 15, 1856, in a vote boycotted by most proslavery men. The result was

the creation of a free-state legislature and the election of Charles L. Robinson as

their territorial governor. The Kansas Territory now ha d two governing bodies—

one proslavery and one that supported a ban. Each considered the other fraudulent.

The conflict they carried with violence by militias on both sides inspired the

phrase “Bleeding Kansas.”

The e lection of a free-state legislature and Robinson’s electio n as governor

amounted to a direct challenge to the authority of the federal government as well

as the proslavery legislature. President Pierce knew that the escalating situation

in Kansas posed a threat to t he credibility of his administration. On January 24,

1856, the president declared the Topeka Constitution to be “revolutionary” and

the Topeka movement to be potentially “treasonable.” He warned that he would

use military force against the Topeka Constitution’s supporters if they actually

formed a government. Alth ough Pierce co ndemned violence by both sides, he

blamed propaganda from northern abolitionists as the initial source of the trouble

and declared that, in spite of irregularities in the March 1855 election, that

government was legitimate.

Pierce’s address had little impact on either side. Both claimants as territorial

governor—Robinson and the newly appointe d proslavery governor, David

Atchison—remained committed to their respective courses of defending the

Topeka Constitution or crushing it. Despit e Pierce’s warning, the Topeka legisla-

ture met on March 4. When it reconvened on July 4 to submit the Topeka

Constitution to Congress for admission to the Union as a free state, it was broken

up by federal troops. Despite the breakup of the Topeka government, its

const itution was sub mitted to Congress. The House of Representatives approved

it later in July, but it failed in the Senate.

With the failure of the Topeka Constitution in Congress, the first effort to gain

Kansas’s admission to the Union ended. Free-staters abandoned the Topeka

Constitution. Its failure, however, only deepened the divisions and intensified the

violence in the Kansas Territory and the nation as a whole. The Topeka

Constitution was followed by three more proposals—the proslavery Lecompton

Constitution of 1857 and the Free-State L eavenworth Constitution of 1858, both

362 Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858)

of which were rejected; and the Wyandotte Constitution, written in 1859 and

passed by Congress in 1861, admitting Kansas as a free state.

—Walter F. Bell

Further Reading

Etcheson, Nicole. Bleeding Kansas: Contested Liberty in the Civil War Era.Lawrence:

University Press of Kansas, 2004.

Goodrich, Thoma s. War to the Knife: Bleeding Kansas, 1854–1861. Lincoln: University of

Nebraska Press, 1988.

Bleeding Kansas (1854–1858) 363

Portland Rum Riot (1855)

The Portland Rum Riot was a shooting incidentthatoccurredwhenthemilitia

fired on a mob in the city of Portland, in Cumberland County, Maine, o n June 2 ,

killing one local man. The mob were essentially demonstrating against the enact-

ment of the “Maine Law,” which had prohibited the consumption, ma nufac ture,

or sale of alcohol, and their anger was specifica lly directed against the town’s

mayor, who was most associated with the new law—and who was actually be ing

accused of having bought alcohol himself.

The person w ho was t he majo r for ce behi nd th e introd uction of this law was

Neal S. Dow (1804–1897), the mayor of Portland, the largest city in Maine and

the state’s original capital before that privilege was given to Augusta. Born in the

city from Quaker pare nts, he had th ought s of enterin g the law, but took over the

family’s successful tanning business and quickly became concerned about the con-

sumption of alcohol in the township. When he was 24, he spoke ou t against the

excessive quantities of liquor consumed at a dinner of the Deluge Engine

Compa ny, of whic h he was then a clerk. Indeed, he became a firefighter to get an

exemption from the mi litia, whose members had a reputation for heavy drinking.

While still in his 20s, Dow established the Maine Temperance Union and urged

that its members insist on the banning of the drinking of all alcohol including wine.

Maine became a state in its own right in 1820 as part of the Missouri Compro-

mise—prior to that it had been a part of Massachusetts—and in 1837, the first bill

to ban alc ohol in Maine was introduced but only reached the commi ttee stage. It

was 12 years later before another bill was put to the Maine legislature. It was

passed, but the governor, John W. Dana, refused to sign it. However in

May 1850, John Hubbard, another Democrat, took over as the new governor of

the state. In April 1851, Dow was elected as mayor of the city of Portland, and

with this extra impetus, Hubbard signed the bill into law on June 2, 1851. Dow

had long been worried that a lax judiciary might not enforce the law, and to help

with its enforcement, there was a mechanism in the act whereby only three voters

could approach a judge who was obliged to issue a search warrant. Dow rapidly

became hailed throughout the United States as the “Napoleon of Temperance”

and went on many s peaking engagements, including becoming the featured

speaker in August 1851 at the fourth National Temperance Convention.

365