Danver Steven L. (Edited). Revolts, Protests, Demonstrations, and Rebellions in American History: An Encyclopedia (ENG)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

But many people disliked the passing of the “Maine Law” banning the produc-

tion or sale of alcohol in the state, and Dow lost his bid for reelection as mayor of

Portland. Nevertheless, he had become so well known throughout North America

that he went on lecture tours of the United States and Canada. In 1854, Dow again

lost election as mayor, but was elected again as mayor in 1855 by 47 votes, having

gained the support of the newly established Republican Party and also having the

secret support of the Know-Nothing Party and many American nativists.

However, rumors spread about claims that Dow himself had violated the Maine

Law. The new law had allowed for the sale of “medicinal and mechanical alcohol,”

and Dow had purchased a shipment of $1,600 worth of alcohol for this purpose,

the alcohol being stockpiled for safekeeping in a building in central Portland. That

doctors and pha rmacists were allowed t o stock alcohol was not well known, and

some aldermen of Portland also claimed that Dow himself had acted illegally in

not ge tting the council to authorize the spending of this amount of money. The

rumors reached members of the Irish community, many of whom were recent

immigrants and resented the new law, which they saw as a move specifically

against them. Three men appeared in front of a judge, who was then compelled

to issue the requisite search warrant. A large crowd gathered in front of the build-

ing where the alcohol was being stored during the afternoon of June 2, and by

5:00 p.m., there were at least 200. Soon afterwards, between 1,000 and 3,000 peo-

ple were gathering in the dusk, some starting to throw stones.

Dow was convinced that the police could not control the crowd if a riot began,

and he called out the local militia with himself, as mayor, taking command.

Worried that the crowd might storm the building and loot the alcohol, Dow

ordered the crowd to disperse, and when they did not, he gave the order for the

militia to open fire. This the militi amen did, and one man, John Robbins, was

killed, with seven others wounded. It seems likely that the militia fired above the

heads of the crowd, because otherwise casualties would have been far more.

Robbins was an immigrant and the mate of a sailing vessel in Maine.

The whole event was referred to by the press the “Portland Rum Riot,” and Dow

himself was arrested and charged with illegal sales of liquor. Nathan Clifford, the

former U.S. attorney general, was the prosecutor, and William P. Fessenden,

another founding member of the Maine Temperan ce Union, was t he defense

attorney. Dow himself was acquitted, but the trial had done its damage, and when

he contested the gubernatorial elections for Maine, he was defeated. In 1856, the

“Maine Law” itself was repealed.

During the American Civil War, Neal Dow served as a colonel and then a briga-

dier general in the Union forces being involved in the capture of New Orleans, and

then was put in charge of two captured Confederate forts. Captured by the Confed-

erates, he spent eight months as a prisoner, but was exchanged in 1864 for General

366 Portland R um Riot (1855)

William Henry Fitzhugh Lee, son of General Robert E. Lee. His health ruined

during his imprisonment, he left the army and devoted his energies to the temper-

anc e movement, stan ding in th e 1880 U.S. presidential election as the candidate

for the Prohibition Party and coming in fourth with 10,305 votes. He spent his last

years writing his memoirs, which were published posthumously.

—Justin Corfield

See also all entries under Philadelphia Nativist Riots (1 844); Know-Nothing Riots

(1855–1856); Day without an Immigrant (2006).

Further Reading

Dow, Neal S. The Reminiscences of Neal Dow: Recollections of Eighty Years. Portland,

ME: Evening Express Publishing Co., 1898.

Rolde, Neal. Maine: A Narrative History. Gardiner, ME: Harpswell Press, 1990.

Westerman, W. Randall. “Ne al S. Dow.” Dictionary of American Biography.NewYork:

Charles Scribner’s Sons, 1964.

Portland Rum Riot (1855) 367

Immigrants

The Portland Rum Riot highlighted differences between the non-Conformists and

Quakers, like Neal Dow, and recently arrived Irish migrants, who had left Ireland

during the 1840s because of the potato famine and saw new opportunities in states

along the East Coast of the United States, including Maine.

The first Irish who came to Maine were Scots-Irish migran ts from Ulster, with

the ship McCallum bringing 20 families in 1718. It was not until after indepen-

dence that an Irish Roman Cathol ic community came to be established with

St. Patrick’s Church; built in Newcastle, Maine, in 1808, it remains the oldest

standing, continuously used Catholic church in New England.

Most of the Irish migrants to Maine h ad left a life of considerable deprivation

for North America. When they settled in Maine, many had found some degree of

prosperity, and the soil was good for the growing of potatoes. It was not long

before a small Irish enclave started to for m in Aroostook County, in the north of

the state. And for those Irish who remained in Portland, there were plenty of

369

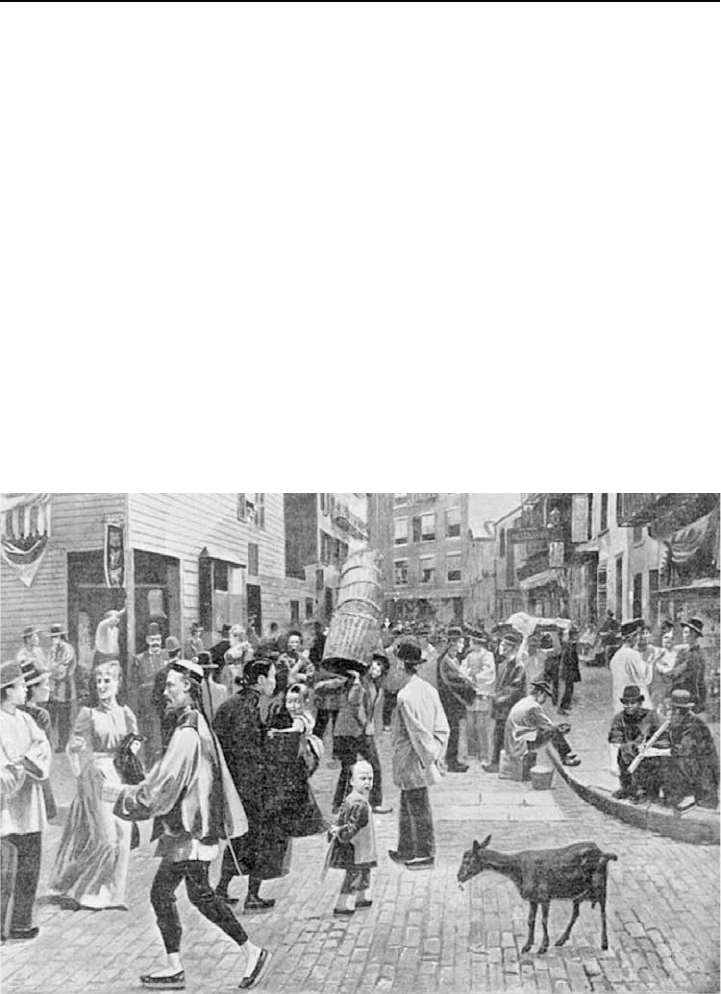

An 1896 illustration from Harper's Weekly of a New York City neighborhood populated by

Chinese immigrants. The population of New York's Chinatown skyrocketed after 1943, when

the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1884 was nullified. (Library of Congress)

taverns and also opportunity to distill their own alcohol. Many of the migrants

became aggrieved at the Maine Law, which banned the sale, manufacture, or con-

sumption of alcohol and found the move by the mayor, Neal Dow, for prohibition

in the entire state onerous. Many Irish also found themselves living in a state that

was heavily non-Conformist and whose governors were all born in New England—

indeed, all but one had been born in New England, and most of them had been born

in Maine; although mentio n should be made of Edwar d Kavanagh, who in 1843

became the first Catholic governor anywhere in Ne w England.

Around the time of the Maine Law, there was some hostility between the local

people and the Catholic migrants, with the 1854 “tarring and feathering” of Father

John Bapst in Ellsworth, and the arson attack on the Old South Church in B ath,

which in 1854 was being used for Catholic services. The other tension was politi-

cal, with the Irish largely supporting the Democrats, but the state steadily becom-

ing more Whig, then controlled by the Know-Nothing Party (which was intensely

anti-Catholic), and then becoming staunchly Republican with the election as gov-

ernor of Hannibal Hamlin in 1857. Hamlin later went on to be Abraham Lincoln’s

first vice president.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Connolly, Michael C., ed. They Change Their Sky: The Irish in Maine. Orono: University

of Maine Press, 2004.

Lucey, William L. The Catholic Church in Maine . Francestown, NH: Marshall Jones,

1957.

Mundy, James H. Hard Times, Hard Men: Maine and the Irish, 1830–1860. Scarborough,

ME: Harp Publications, 1990.

Temperance

The temperance movement had long been active among non-Conformists and

Quakers in the United States, and they pointed to the obvious social problems that

had been created by excessive consumption of alcohol. In London, William

Hogarth’s drawings of gin drinkers were famous, and John Wesley (1703–1791)

preached throughout England leading to the establishment of Methodism, in which

adherents did not drink alcohol. Some people did feel that there were exceptions,

such as the use of communion wine in very limited amounts, or some spirits

for medicinal purposes, or indeed for industrial purposes, including its use as a

cleaning agent.

370 Portland R um Riot (1855)

In the United States, as in Britain, the temperance movement was heavily asso-

ciated with churches, the first temperance organization in the United States having

been established in Saratoga, New York, in 1808, and in Massachusetts five years

later. Many people had been alerted to the problem by the Whiskey Rebellion in

1794, and by the early 19th century, with the increasing prosperity of the United

States and its own large alcohol producing industries, the problem of drunkenness

was becoming noticeable. By 1833, there were as many as 6,000 local temperance

societies around the United States, and boys and girls would pledge not to drink

any alcohol. Many women supported this move, and in 1851, the Order of Goo d

Templars was established at Utica, New York, the fi rst international temperance

organization.

Neal S. Dow was un doubtedly influenced by his Quaker background, and he

deplored the public drunkenness that was occasionally seen in Portland, especially

with the newly arrived Irish community. The issues of law and order, and the social

problems that resulted, were obvious to many, and for that reason, Dow’s move to

ban the manufacture and sale of alcohol in Maine was initially popular. However,

Dow’s laws were seen as overbearing, and the ease at which a search warrant could

be acquired—as Dow himself found out—showed that the system was open to

personal vendettas.

Although the “Maine Law” was repealed in 1856, after being on the statute

books for only five years, it did show that it was possible to get a majority of peo-

ple and legislators to agree to prohibition, although Dow’s later contesting the

presidential election on that platform showed that when it served as a single issue

for a political party, the public would return to their allegiance to the Democrats or

the Republicans. In 1888 and in 1892, the Prohibition Party managed only just

over 2 percent of the vote on each occasion. However the Woman’s Christian Tem-

perance Union was established in 1874 at Cleveland, Ohio, pressure mounted for

the enactment of Prohibition in the United States, and the issue was certainly

popular on a county and local level.

In 1919 , the U.S. Congress passed the Volstead A ct, which prohibited the sale

or manufacture of a lcohol for consumption anywhere in th e United States.

Although it did have widespread success, it did lead to the emergence of wealthy

gangsters like Al Capone, who smuggled illicit alcohol into the country and sold

it at vast profits. Prohibition ended in 1933.

—Justin Corfield

Further Reading

Cherrington, Ernest. Evolution of Prohibition in the United States. Westerville, OH: The

American Issue Press, 1926.

Clark, Norman H. Deliver Us from Evil: An Interpretation of American Prohibition.

New York: W. W. Norton, 1976.

Portland Rum Riot (1855) 371

Know-Nothing Riots

(1855–1856)

The American Party, common ly called the “Know-Nothing Party,” was a part of

the American nativist movement, which became powerful in the p eriod from

1854 until 1856. It was involved in clashes with Roman Catholics, predominantly

Irish ones, the worst ones being those involving gangs such as the Plug Uglies and

the Rip Raps in Baltimore, Maryland, and also in New York City.

There ha d been risin g anti–Roman Catholic senti ment throughout the United

States in the 1840s with the influx of many Irish migrants escaping the potato fam-

ine. Later, Germans started arriving, with many fleeing the political turmoil in

Germany during 1848. People against these migrants sta rted gathering i n clubs,

with the Order of the Star-Spangled Banner being fo rmed in New York City in

secret in 1849, and similar lodges being set up in other major cities. The secrecy

of the organization meant that when members were asked about their group, they

replied that they knew nothing about it, the name being retained by the nativist

supporters, and then by the American Party when it was established in 1855,

emerging out of the American Republican Party which had been f ormed in New

York in 1843. Because of its populist background, and because it cut across both

the Democrats and the newly established Republican Party, it managed to do well

in elections in the early 1850s. This came about because the Democratic Party was

divid ed on the issue of slavery, and with the Republicans firmly against slavery,

the Know-Nothing Party managed to get defectors from both parties. As a result,

in December 1855, some 43 members of the U.S. House of Representatives were

publicly stated to be members of the Know-Nothing Party, with a party convention

held in Philadelphia in 1856.

As a political organization, the Know-Nothing Party wanted to exclude any-

body born outside the U nited States from voting or holding public office in the

country, and also restrict immigration through a residency requirement for citizen-

ship to be extended to 21 years. Obviously drawing support from xenophobic sec-

tions of the population, it was not long before members and supporters of the

Know-Nothing Party became involved in scuffles with opponents.

Much of the initial focus of the party was directed against Irish and German

immigrants , and as some states had made it easy to become naturalized, the

373

number of Irish and German voters in these states was increasing at a rate far

higher than the native-born population. Fearing that these immigrants could form

solid voting blocks, attacks began on them in the press, accusing them of spread-

ing crime, drunkenness, and living from begging and vagrancy as well as pushing

down wages and raising the cost of renting property.

As many as 1.5 million people joined the Know-Nothing Party during the early

1850 s, and it quickly came to dominate the political scene in New England with

the exception of Vermont and Maine. Riots by supporters of the Know-Nothing

Party tended to involve attacks on Roman Catholic churches as Protestants saw

that Pope Pius IX had opposed the liberal Revolutions in Europe in 1848 and

was therefore an opponent of democracy and personal freedoms. Some of the

attacks were isolated, but many were coordinated with help from like-minded

politicians and occasionally with the connivance of civic authorities.

Some of the rioting and attacks on immigrants took place in Baltimore, Maryland,

in October 1856, when Thomas Swann was contesting the election for mayor.

Swann, the candidate of the Know-Nothing Party, had the support of three gangs,

the Plug Uglies, the Rip Raps, and the Wompanoag—the Rip Raps being responsible

for an attack on the Democrats in which two Democrats were killed and 20 others

were badly injured. In the previous elections in October 1854, the Know-Nothing

Party had managed to win a majority on the Baltimore City Council and get Samuel

Hinks elected as mayor. Howe v er, they had lost support in the municipal elections in

1855 and so were anxious to win in 1856.

Swann did indeed win the electi on, and indeed Millard Fillmore, the former

president and the Know-Nothing Party candidate, won Maryland in the presiden-

tial elections, the only state he carried. However, the outcry against the election

violence was so bad that Swann was forced to change the nature of the police force

and also the fire brigade, resulting in the gangs losing the power they had wielded

so freely to get Swann elected. Much of this was because of the murder of police-

man Benjamin Benton by Henry Gambrill from the Plug Uglies—Gambrill had

shot the policeman at point-blank range with a revolver, and was arrested. Many

stre et fights escalated over support or opposition to Gambrill and whether or no t

his crime was politically motivated. This came at a time when Baltimore was split

between the supporters and opponents of slavery. Gambrill himself was found

guilty, sentenced to death, and duly hanged. The judge who presided over the

trial, Henry Stump, was himself later removed from the bench for unrelated

“misbehavior.”

There were also riots in New York City, but these are believed to have been

greatly affected by some people from B altimore. T he party had already declin ed

by the elections in 1856 as it started to show splits over slavery, which was emerg-

ing as th e major issue in U.S. politics. The rise of the Republican Party eclipsed

374 Know-Nothing Riots (1855–1856)

the Know-Nothing Party, and in the presidential elections, the Know-Nothing

Party backed former president Millard Fillmore, although there were doubts over

his actual loyalty to the party, and many Know-Nothing members voted for John

Fremont of the Republican Party. Although it fielded 48 candidates for sears in

six states in the North, only one member of the Know-Nothing Party managed to

get elected.

On June 1, 1857, there was a small riot when a group of Know-Nothing support-

ers from Baltimore went to Washington, D.C., to help “influence” voters going to

the polls for the municipal elections. Marines opened fire, killing 10 men, but only

one of these was from Baltimore.

—Justin Corfield

See also all entries under Philadelphia Nativist Riot s (1844); Por tland Rum Riot (1 855) ;

Day without an Immigra nt (2006).

Further Reading

Anbinder, Tyler. Nativism and Slavery: K now Nothings and the Politics of the 1850s.

Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 1992.

Billington, Ray A. The Protestant Crusade, 1800–1860: A Study of the Origins of American

Nativism. New York: Macmillan, 1938.

Hurt, Payton. “The Rise and Fall of the ‘Know Nothings’ in California.” California

Historical Society Quarterly 9 (March–June 1930).

Overdyke, W. Darrell. The Know-Nothing Party i n the South. Baton Rouge: Louisiana

State University Press, 1950.

Know-Nothing Riots (1855–1856) 375