Choudhry. Fixed Income Securities Derivatives Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

312 Selected Market Trading Considerations

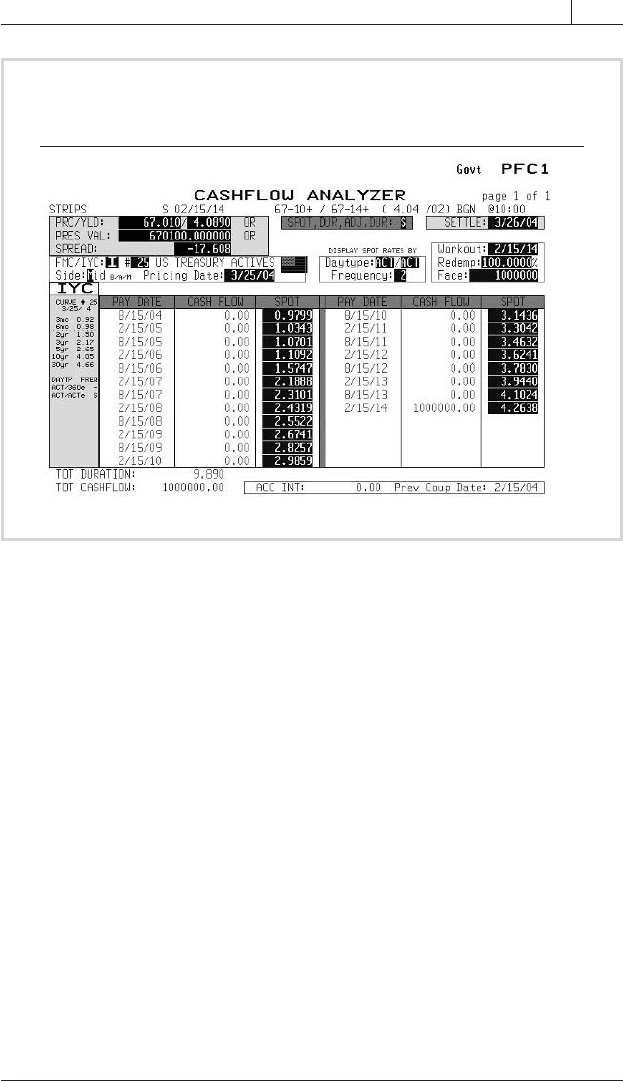

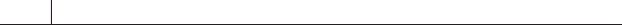

FIGURE 16.10

Cash Flow Analysis of the 4 Percent Treasury

2014 Principal Strip, at a Yield of 4.075 Percent

Source: Bloomberg

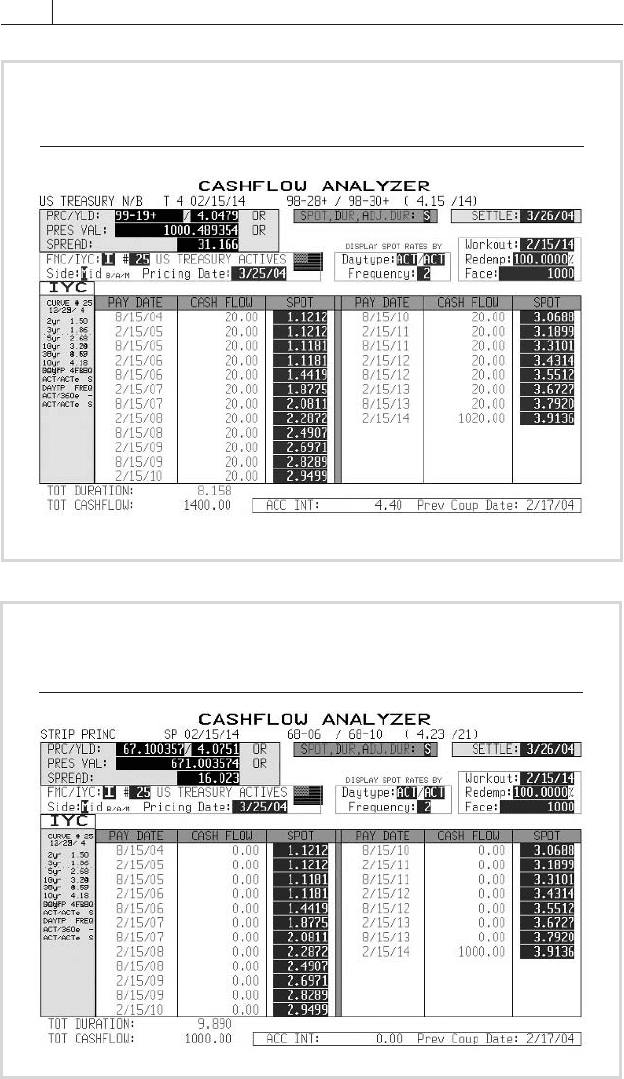

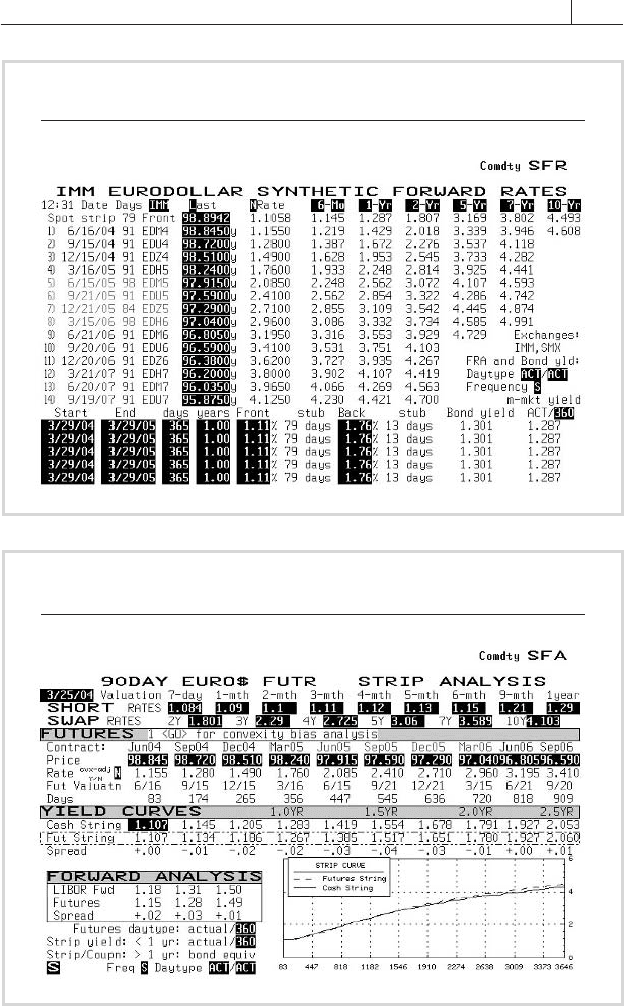

FIGURE 16.9

Cash Flow Analysis of the 4 Percent Treasury

Due 2014

Source: Bloomberg

The Yield Curve, Bond Yield, and Spot Rates 313

curve. There is only one cash fl ow: the redemption payment, which equals

$1 million for a holding of $1 million nominal. The principal strip’s

convexity is higher than the coupon bond’s, as is its duration, again as

expected.

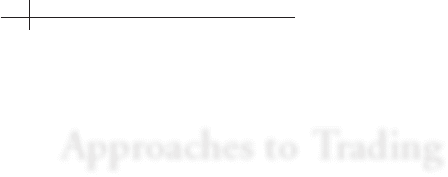

Finally,

FIGURE 16.11 shows the cash fl ow analysis for the coupon

strip maturing on February 15, 2014, and trading at a yield of 4.089

percent, for a price of 67.01 per $100 nominal. This illustrates an

anomaly noted earlier: although the law of one price states that all strips

maturing on the same date should cost the same—after all, why would

investors require a different yield for a payment of interest than for one

of principal?—principal strips in fact trade at lower yields than coupon

strips, because they are more liquid and so more sought after.

Chapter Notes

1. In fact, this date is a Saturday, so the actual redemption proceeds will be paid on

Monday, February 17, 2014.

FIGURE 16.11

Cash Flow Analysis of the February 2014 Coupon

Strip, at a Yield of 4.089 Percent

Source: Bloomberg

This page is intentionally blank

315

CHAPTER 17

Approaches to Trading

T

he term trading covers a wide range of activities. Market makers,

who quote two-way prices to market participants, may also be

asked to provide customer service and build retail and institu-

tional volume. Alternatively, their sole responsibility may be to run their

books at a profi t and maximize return on capital.

Trading approaches are determined in part by the nature of the market

involved. In a highly transparent and liquid market, such as that for U.S.

Treasuries, price spreads are fairly narrow, so opportunities to profi t from

the mispricing of individual securities, although not nonexistent, are rare.

Participants in such markets may engage in relative value trades, or spread

trading, which involves relationships such as the yield spread between

individual securities or the future shape of the yield curve. On the deriva-

tives exchanges, a large volume of the trading is for hedging purposes, but

speculation is also prominent. Bond and interest rate traders often use

futures or options contracts to bet on the direction of particular markets.

This is frequently the case with market makers who have little customer

business—whether because they are newcomers, for historical reasons, or

because they don’t want the risk related to servicing high-quality custom-

ers. They speculate to relieve the tedium, often with unfortunate results.

Speculative trading is based on the views of the trader, the desk, or

the department head. The view may be that of the fi rm’s economics or

research department—based on macro- and microeconomic factors affect-

ing not just the specifi c market but the economy as a whole—or it may

be that of the individual trader, resulting from fundamental and technical

316 Selected Market Trading Considerations

analysis. Because credit spreads are key to the performance of corporate

bonds, those running corporate-debt desks focus on the fundamentals

driving those spreads, concentrating on individual sectors as well as on the

corporations themselves and their wider environment. Technical analysis,

or charting, is based on the belief that the patterns displayed by continu-

ous-time series of asset prices repeat themselves. By detecting current pat-

terns, therefore, traders should be able to predict reasonably well how

prices will behave in the future. Many traders combine fundamental and

technical analysis, although chartists often say that for technical analysis to

work effectively, it must be the only method used.

Futures Trading

Because of the liquidity of their market and the ease and relative cheap-

ness of trading them, futures and other derivatives are often preferred to

cash instruments, for both speculation and hedging. The essential consid-

erations in futures trading are the volatility of the associated commodity

or fi nancial instrument and the leverage deriving from the fact that the

margin required to establish a futures position is a very small percentage of

the contract’s notional value.

Uncovered trades, made without owning the underlying asset, are

speculative bets on the direction of the market. Traders who believe short-

term U.S. interest rates are going to fall, for example, might buy Eurodol-

lar contracts—representing the level, at contract expiration, of the interest

rate on a 3-month deposit of $1 million in commercial banks located

outside the United States—on the Chicago Mercantile Exchange (CME).

The contracts’ tick value—the price change associated with a movement

of 0.005 of a percentage point in the interest rate—is $12.50. Say a trader

buys one lot at 98.84, representing a future interest rate of 1.16 (100

– 98.84 percent) percent, and sells it at the end of the day for 98.85, rep-

resenting a rate of 1.15 percent. That’s a rise of 0.01, or two ticks, resulting

in a profi t of $25, from which brokerage fees are subtracted.

Traders can also bet on their interest rate views using a cash-market

product or a forward rate agreement (FRA)—a contract specifying the

rate to be received or paid starting at specifi ed future date. Transactions

are easier and cheaper, however, on the futures exchange, because of the

low cost of dealing there and the liquidity of the market and narrow price

spreads.

More common than directional bets are trades on the spread between

the rates of two different contracts. Consider

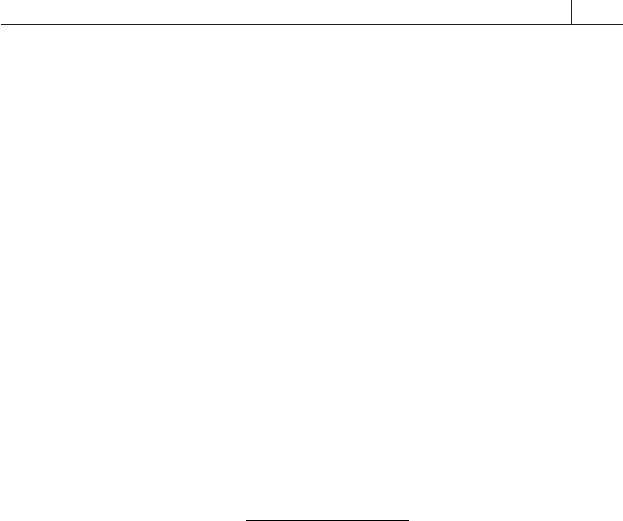

FIGURES 17.1 and 17.2, both

of which relate to the prices for the CME Eurodollar contract on March

24, 2004 (contracts exist for every month in the year).

Approaches to Trading 317

Futures exchanges use the letters H, M, U, and Z to refer to the con-

tract months March, June, September, and December. The June 2004

contract, for example, is denoted by “M4.” Forward rates can be calcu-

lated for any term, starting on any date. Figure 17.1 shows the futures

Source: Bloomberg

FIGURE 17.1 CME 90-Day Eurodollar Synthetic Forward Rates

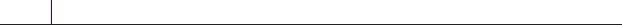

Source: Bloomberg

FIGURE 17.2 CME 90-Day Eurodollar Futures Strip Analysis

318 Selected Market Trading Considerations

prices on that day and the interest rate that each price implies. The stub

is the interest rate from the current date to the expiry of the fi rst, or front

month, contract—in this case, the June 2004 contract. Figure 17.2 lists the

forward rates for six months, one year, and so on from the spot date. It is

possible to trade a strip of contracts replicating any term out to the maxi-

mum maturity of the contract. This may be done to hedge or to speculate.

Figure 17.2 shows that a spread exists between the cash and futures curves.

It is possible to take positions on cash against futures, but it is easier to

trade only on the futures exchange.

Short-term money market rates often behave independently of the

yield curve as a whole. Traders in this market watch for cash market

trends—more frequent borrowing at a certain point in the curve, for ex-

ample, or market intelligence suggesting that one point of the curve will

rise or fall relative to others. One way to exploit these trends is with a basis

spread trade, running a position in a cash instrument such as a CD against

a futures contract. The best way, though, is with a spread trade, shorting

one contract against a long position in another. Say you believe that in

June 2004 3-month interest rates will be lower than those implied by the

current futures price, shown in Figure 17.1, but that in September 2004

they will be higher. You can exploit this view by buying the M4 contract

and shorting an equal weight of the U4—say one hundred lots of each.

In doing so, you are betting not on the market direction but on the spread

between two contracts. If rates move as you expect, you realize a profi t.

Because it carries no directional risk, spread trading requires less margin

than open-position trading. Figure 17.2 presents similar trade possibili-

ties, depending on your view of forward interest rates. It is also possible to

arbitrage between contracts on different exchanges.

In the example above, you are shorting the spread, believing that it

will narrow. Taking the opposite positions—short the near contract and

long the far one—is buying the spread. This is done when the trader be-

lieves the spread will widen. Note that the difference between the two

contracts’ prices is not limitless: a futures contract’s theoretical price

provides an upper limit to the size of the spread or the basis, which,

moreover, cannot exceed the cost of carry—that is, the net cost of buy-

ing the cash security today and delivering it into the futures market at

contract expiry. The same principle applies to short-dated interest rate

contracts, where cost of carry equals the difference between the interest

cost of borrowing funds to buy the security and the income generated

by holding it until delivery. The two associated costs for a Eurodollar

spread trade are the notional borrowing and lending rates for buying one

contract and selling another.

Approaches to Trading 319

Traders who believe the cost of carry will decrease can sell the spread to

exploit this view. Those with longer time horizons might trade the spread

between the short-term interest rate contract and the long bond future.

Such transactions are usually done by proprietary traders, because it is

unlikely that one desk would be trading both 3-month and 10- or 20-year

interest rates. A common example is a yield curve trade. Say you believe

the U.S. dollar yield curve will steepen or fl atten between the 3-month

and the 10-year terms. You can buy or sell the spread using the CME

90-day Eurodollar contract and the U.S. Treasury 10-year note contract,

traded on CBOT. Because one 90-day interest rate contract is not equiva-

lent to one bond contract, however, the trade must be duration-weighted

to be fi rst-order risk neutral. The note contract represents $100,000 of a

notional Treasury, although its tick value is $15.625; the Eurodollar con-

tract represents a $1 million time deposit. Equation (17.1) calculates the

hedge ratio, with $1,000 being the value of a 1 percent change in the value

of each contract.

h

tick P D

tick P

b

f

short ir

f

=

×

()

××

×

()

×

100

100

(17.1)

where

tick = the tick value of the contract

D = the duration of the bond represented by the long bond contract

P

b

f

= the price of the bond futures contract

P

short ir

f

= the price of the short-term deposit contract

The notional maturity of a long-bond contract is always given as a

range: for the contract on the 10-year note, for example, it is six to ten

years. The duration used to calculate the hedge ratio would be that of the

cheapest-to-deliver bond.

A butterfl y spread involves two spreads between three contracts, the

middle of which is perceived to be mispriced relative to the other two. The

underlying concept is that the market will correct this mispricing, chang-

ing the middle contract’s relation to the outer contracts. Traders put on a

butterfl y when they are not sure which contract or contracts will move to

effect this adjustment.

Consider fi gure 17.1 again. The prices of the front three contracts are

98.84, 98.72, and 98.51. Traders may feel that the September contract, at

a spread of +12.5 basis points to the June contract and –21 basis points to

the December one, is undervalued. The question is, will this be corrected

by a fall in the June and December prices or by a rise in the September

one? The traders don’t need to choose. If they believe that the spread be-

320 Selected Market Trading Considerations

tween the June and September contracts will widen and the one between

the September and December contracts will narrow, they can put on a

butterfl y spread by buying the fi rst and selling the second. This is also

known as selling the butterfl y spread.

Yield Curves and Relative Value

Bond market participants take a keen interest in both the cash and the

zero-coupon (spot) yield curves. In markets where an active zero-coupon

bond market exists, the spreads between implied and actual zero-coupon

yields also receive much attention.

Determinants of Government Bond Yields

Market makers in government bonds consider various factors in deciding

how to run their books. Customer business apart, decisions to purchase or

sell securities will depend on their views about the following:

❑ whether short- and long-term interest rates are headed up or

down

❑ which maturity point along the entire term structure offers the best

value

❑ which of the issues having that maturity offers the best value

These three factors are related but are affected differently by market-

moving events. A report on the projected size of the government’s budget

defi cit, for example, will not have much effect on two-year bond yields, but

if the projections are unexpected, they could adversely affect long-bond

yields. The type of effect—negative or positive—depends on whether the

projections were higher or lower than anticipated.

For a fi rst-level analysis, many market practitioners look no further

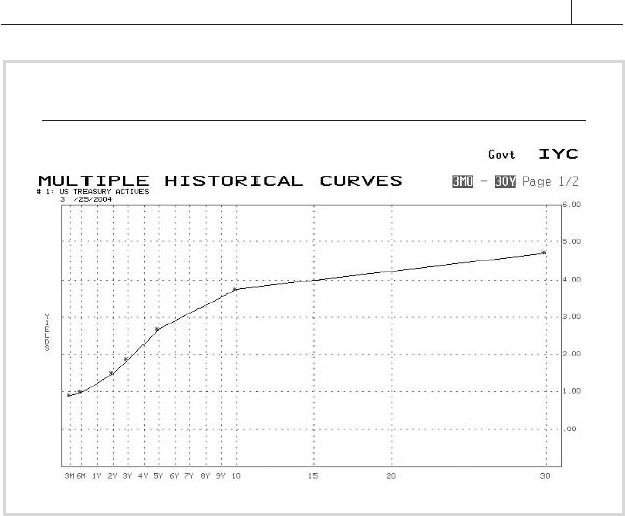

than the traditional yield curve like the one shown in

FIGURE 17.3. Inves-

tors with no particular views on the future shape of the curve or level of

interest rates might adopt a neutral strategy, holding bonds with durations

matching their investment horizons. If the curve is positive and they be-

lieve interest rates are likely to remain stable for a time, they might buy

bonds with longer durations, thus picking up additional yield but increas-

ing their interest rate risk.

Once investors have determined which part of the yield curve to invest

in or switch into, they must select specifi c issues. To make an informed

choice, they use relative value analysis.

Relative value analysis focuses on bond issues located in certain

sectors, or “local” parts, of the curve. Because a bond’s yield is a func-

tion not just of its duration—after all, two issues with near-identical

Approaches to Trading 321

duration can have different yields—the analysis assesses other factors as

well. These include liquidity, the interplay of supply and demand, and

coupon rate, all of which affect yield.

FIGURE 17.4 illustrates the impact

of coupon rate.

The fi gure shows that, when the curve is inverted, investors can pick

up yield while shortening duration. This might seem an anomalous situ-

ation, but in fact, liquidity issues aside, the market generally disfavors

bonds with high coupons, so these usually trade cheap to the curve.

As with any commodity, supply and demand also play important roles

in determining bond prices, and therefore their yields. A shortage of is-

sues at a particular point in the curve—the result, perhaps, of an effort

to reduce public-sector debt—depresses yields for that maturity. On the

other hand, when interest rates decline—ahead of or during a recession,

say—and new bonds are issued with increasingly lower coupons, the stock

of “outdated” high-coupon bonds increases and can end up trading at a

higher yield.

Demand is a function primarily of investors’ views of a country’s eco-

nomic prospects. It can also be affected, however, by government actions,

such as the debt-buyback program instituted during the last years of the

Clinton administration in response to the budget surplus. These buybacks

reduced the supply of bonds in the market, artifi cially depressing yields

because demand could not be met, especially for 30-year bonds, which the

FIGURE 17.3 U.S. Treasury Yield Curve, March 25, 2004

Source: Bloomberg