Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Uzzi, B. (1999) Embeddedness in the making of financial capital: how social relations

and networks benefit firms seeking financing. American Sociological Review 64,

481–505.

Weder, R. and Grubel, H.G. (1993) The new growth theory and Coasean economics:

institutions to capture externalities. Weltwirtschaftliches Archiv, 488–513.

Williamson, O.E. (1975) Markets and Hierarchies: Analysis and Antitrust Implications.

New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O.E. (1985) The Economic Institutions of Capitalism. New York: Free Press.

Williamson, O.E. (1991) Comparative economic organization: the analysis of discrete

structural alternatives. Administrative Science Quarterly 36, 269–96.

Woolcock, M. (1998) Social capital and economic development: toward a theoretical

synthesis and policy framework. Theory and Society 27, 151–208.

Xin, K.R. and Pearce, J.L. (1996) Guanxi: connections as substitutes for formal insti-

tutional support. Academy of Management Journal 39(6), 1641–58.

You, J. and Wilkinson, F. (1994) Competition and cooperation: towards understanding

industrial districts. Review of Political Economy 6, 259–78.

Zukin, S. and DiMaggio, P. (eds) (1990) Structures of Capital: the Social Organization of

the Economy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 521

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 521

Learning Objectives

By the end of this chapter you will be able to:

explain the complementarity of three core societal institutions – that is, the

systems of corporate governance, personnel and industrial relations

understand the need to distinguish between different levels of analysis when

tracing the impact of globalization forces

analyse the effect of the so-called globalization forces upon the three

aforementioned societal frameworks

reflect critically on the plausibility of path-deviant change in organization and

management

appraise whether institutional theory is sufficiently powerful to analyse the

impact of globalization pressures

evaluate the role of cultural characteristics in explaining change at the societal,

organization and management levels

reflect on the link between globlization and MNCs.

Chapter

12

Globalization,

Convergence and

Societal Specificity

522 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 522

Chapter Outline

12.1 Introduction

12.2 Corporate Governance

12.3 The Personnel and Industrial Relations Systems

Germany

Japan

12.4 Conclusions

Study Questions

Further Reading

Case: Global Outsourcing: Divergence or Convergence?

References

GLOBALIZATION, CONVERGENCE AND SOCIETAL SPECIFICITY 523

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 523

12.1 Introduction

As mentioned in the introduction to this book, the different opinions on the consequences

of global forces form the starting point of this chapter. As also explained in the introduc-

tion, the globalization literature exhibits divergent opinions on the consequences of

globalization, which can be summarized in four possible scenarios.

1. Convergence towards the Anglo-American neoliberal market system (i.e. Dore, 1996;

Streeten, 1996; Streeck, 1997).

2. Greater specialization of national models in accordance with domestic institutional

and cultural characteristics (Vitols, 2001; Sorge, 2003).

3. Incremental adaptation of the domestic institutional context in a largely path-

dependent manner (i.e. Whitley, 1994; Casper, 2000)

4. Hybridization with change in a path-deviant manner (i.e. Whitley, 1999; Lane, 2000).

In Chapter 4, we developed some theoretical concepts, which can help us understand

institutional change as a result of global pressures. Among other things, these concepts

stress that when we consider only single social institutions in trying to understand the

effects of globalization, this may be misleading because it denies the genuine nature of the

social institutional architecture, which is combinative. We argued that, in order to under-

stand the impact of globalization on the domestic context and as a corollary on

management and organization, we need to study how social institutions are complemen-

tary to one another, in the sense that one institution functions better because some other

particular institutions or forms of organization are present (Amable, 2000). Hence, when

analysing the effects of global pressures, we have to take account of the possible (destabi-

lizing) effect of change and resilience in one element of the social system on other elements.

This chapter uses the dynamic concepts, explained in Chapter 4, to analyse further

the directions of change in the relevant managerial fields that have been studied in this

book. It tries to identify the impact on management and organization of diverging and/or

converging tendencies in major societal institutions in Germany and Japan in comparison

with the USA and the UK. The chapter is restricted to these four countries as they are the

prototype countries of the two major societal models: the Rhineland model and the

Anglo-Saxon model, respectively. Most, if not all, other industrialized countries are situ-

ated somewhere on the continuum between the two. It could be argued that if

globalization were to have an impact, we should be able to identify changes in the societal

context of the core representatives of the two major capitalist models.

While we have identified societal change in the relevant chapters of this book, we

have postponed to this chapter the drawing of conclusions. In view of the complementary

character of institutions, and because the different chapters concentrate on only one set

of societal institutions, we were unable to make legitimate claims for one or other direc-

tion of change. We did reflect somewhat on the predictions of many scholars, which

suggest convergence of the Rhineland model towards the Anglo-Saxon model. This claim

should be seen against the background of the recession, in Japan and Germany, from the

late 1990s onwards, and the establishment of regulatory changes by the German and

Japanese governments in answer to this recession.

524 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 524

This chapter, in contrast, while recognizing that these reforms are path deviant and

seem to point towards convergence, explains how they, nevertheless, induced path-

dependent adaptation of organization and management practices as well as further

specialization of the industrial profile. This observation leads to the warning that it is

important to make a clear distinction between the levels at which one analyses the impact

of globalization. Analysis at the societal level, while having an impact on organization

and management, is not sufficient to legitimize claims for all types of change. True, it

could be argued that the effect of societal change on management and organization

might be slower than the effect of globalization on the societal level. In Chapter 4, we

argued, however, that path-deviant change at the societal level does not necessarily lead

to path-deviant change in organization and management, as there are other dynamics at

work at that level of analysis.

We will concentrate in this chapter on assessing the direction and type of change in

three main societal frames – that is, the corporate governance system and the personnel

and industrial relations systems. From Chapter 7, on production management, and

Chapter 8, on national innovation systems, it should be clear that these three societal set-

tings are complementary and that change in one of them would necessarily trigger

change in another in order to preserve the coherence, efficiency and stability of the entire

societal system. In these chapters, it was shown that the combination of these three soci-

etal frames allows us to explain the differences in production models and innovation

systems between countries.

Briefly, in Chapter 7 we saw that the combination of capital market finance, absence

of substantial training for workers, short-term contracts and arm’s-length industrial

relations helped us to explain the competitive position of the USA and the UK in mass-

production sectors. Conversely, long-term patient capital, high-quality training, long-

term employment, and close industrial relations helped us to understand the competitive

position of the German and Japanese flexible production models. Chapter 8 showed that

the combination of venture capital, which allows high risk taking, an active labour

market of the scientists and financial experts needed to form start-up companies, and

strong financial incentives based on share options, helps us to explain the competitive pos-

ition of US and UK firms in radical forms of innovation. Conversely, constraints on the

provision of venture capital created by the broadly bank-centred orientation of German

and Japanese capital markets, rigidities in the labour market for scientists and managers,

and inadequate performance incentives within German and Japanese firms, help us to

explain the competitive position of German and Japanese firms in incremental types of

innovation.

So, in the following, we will first discuss recent changes in the societal systems of cor-

porate governance, personnel and industrial relations. Next, we briefly elaborate on the

conclusions that are drawn from these changes and, finally, we look at the significance of

our conclusions for managing multinational operations.

12.2 Corporate Governance

To simplify the discussion of a complex topic, it is useful to distinguish between the two main

models of corporate governance, which are discussed at length in Chapter 6, on corporate

GLOBALIZATION, CONVERGENCE AND SOCIETAL SPECIFICITY 525

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 525

governance: the ‘outsider’, or the Anglo-Saxon system, and the ‘insider’ model, like the

German and Japanese systems. The distinction between the two systems is often made in

terms of whether the banks play a dominant role or whether the stock market is the main

locus of monitoring and control. The take-over mechanism is at the heart of the Anglo-

Saxon open market model of corporate governance. Any party can bid for the control

rights of a listed company by accumulating a large enough ownership stake. The building

blocks of the insider-based system of corporate governance in Germany and Japan are the

important role played by the banks as large creditors and large parent firms, and the high

degree of interlocking shareholdings. In contrast to UK and US views of the firm as a

property of owners, who are the sole ‘residual claimants’, German and Japanese cor-

porate governance has drawn lesser distinctions between the private rights of owners and

social or political obligations in the context of social groups or society.

In the context of the globalization debate, neoclassical orthodoxy claims that one or

the other corporte governance model is economically superior and that, over time, we

should see convergence towards this model of ‘best practice’. The shareholder or outsider

model was heavily criticized in the early 1990s for its tendencies to under-invest and to

focus on short-term results (Porter, 1990). At present, however, the majority view is that

the shareholder model will prevail due to the globalization of capital markets and the

growing power of institutional investors. The argument is that, since international capital

markets are increasingly dominated by diversified portfolio investors (such as mutual funds

and pension funds) seeking higher returns, companies must adopt the shareholder model

or be starved of the external capital needed to invest and survive (Lazonick and O’Sullivan,

2000, cited in Vitols, 2001).

The main question is: ‘Is the stakeholder model of corporate governance changing towards

the shareholder model as a result of globalization pressures?’ In order to investigate this claim

– that is, in order to be able to judge the plausibility of a shift of the insider-orientated

model towards the outsider or shareholder model – it is useful to look at the developments

of four major interrelated and complementary categories of the German and Japanese

corporate governance systems:

1. formal legal and regulatory changes

2. changes in the structure of corporate ownership

3. growth of the stock market, and

4. emergence of a market for corporate control (Coffee, 2001).

Taken in isolation, one aspect of a system, such as stable shareholding arrangements

in Germany and Japan, may appear arbitrary or even reprehensible when wanting to

judge the direction of change. Especially since – despite the lack of agreement on the

direction of causality – there is widespread agreement in the literature that changes in

one of these categories would affect the others (Nowak, 2001). One school of thought

holds that law affects the economic system (La Porta et al., 1997; Roe, 1997), while

another argues that law and regulation are likely to be a result of the economic system

(Easterbrook, 1997). In any case, the assumptions of dialectical relationships between

systemic elements and the tendency for institutional coherence imply that, when change

in one of the aforementioned categories occurs, we should expect change in another.

The most important regulatory changes in Germany and Japan in the past few years

526 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 526

in the area of corporate governance have been in the area of company law and financial

regulation. In the 1990s, to increase the attractiveness of German capital markets,

German legislators initiated the Second and Third Laws for the Promotion of Financial

Markets. The Second Law (established in 1994) set up an Anglo-Saxon-style Federal

Securities Supervisory Office (Bundesaufsichtsamt für Wertpapierhandel) and imposed the

first formal German prohibition of insider trading. The Third Law (passed in 1997) liber-

alizes restrictions on mutual funds and venture capital companies, and allows more

liberal listing requirements, to try to encourage more German and foreign companies to

list on the German stock exchanges, and also to expand the access to capital of small and

medium-sized enterprises (Schaede, 1999; Nowak, 2001; Vitols, 2001).

A significant reform of German company law was effected through the Law for

Corporate Control and Transparency in Large Companies (KonTraG), which modifies the

Joint Stock Company Law 1965 (Aktiengesetz). The law was an initiative of the Kohl gov-

ernment as a political response to a number of major failures of supervisory board

administration. The primary goals of the KonTraG, which became effective in May 1998,

were to improve the monitoring effectiveness of German supervisory boards and corporate

disclosure to the investment community. In addition, the legal liability of the management

board in case of dishonest or fraudulent behaviour was also tightened. In order to provide

the management with proper performance-based incentives, the KonTraG also simplifies

the use of stock option programmes through share buybacks and capital increases,

allowing German companies to adopt ‘typical’ Anglo-Saxon practices (Nowak, 2001).

Although these reforms have led to a somewhat more liquid and transparent stock

exchange for the largest German companies (particularly the largest 30 companies con-

tained in the Deutscher Aktienindex, or DAX), most significant are the elements of

continuity that remain. The vast majority of German companies are not listed on the

stock exchange, remain embedded in ‘relational networks’, including their local banks,

and continue to receive their external finance mainly in the form of bank loans. The most

important banking group – especially for the vast Mittelstand (small and medium-sized

companies) – remains the publicly owned municipal savings bank sector (Sparkassen),

which continues to account for more than half of all banking system assets in Germany

(Vitols, 2001: 348).

Small- and medium-sized enterprise (SME) owners have been criticized for avoiding

listing in order to prevent any dilution of their control and for their unwillingness to

reveal profitability (Herr im Hause Mentalität). Such SMEs have not made much use of

share capital as a means of fulfilling their growing financing needs, despite reforms aimed

at making it easier for them to do so (the 1986 introduction of a Second Market, or

geregelter Markt and the 1994 Law on Small Public Companies, or Gesetz über Kleine

Aktiengesellschaften). The SMEs, on the other hand, argue that there remain barriers to

listing. For example, continuing credit institutions – in effect, banks – must be involved in

the first segment of trading (i.e. issuing shares). As the banks are concerned about their

reputation, they are thought to be careful about dealing with new entrepreneurs (Vitols

and Woolcock, 1997).

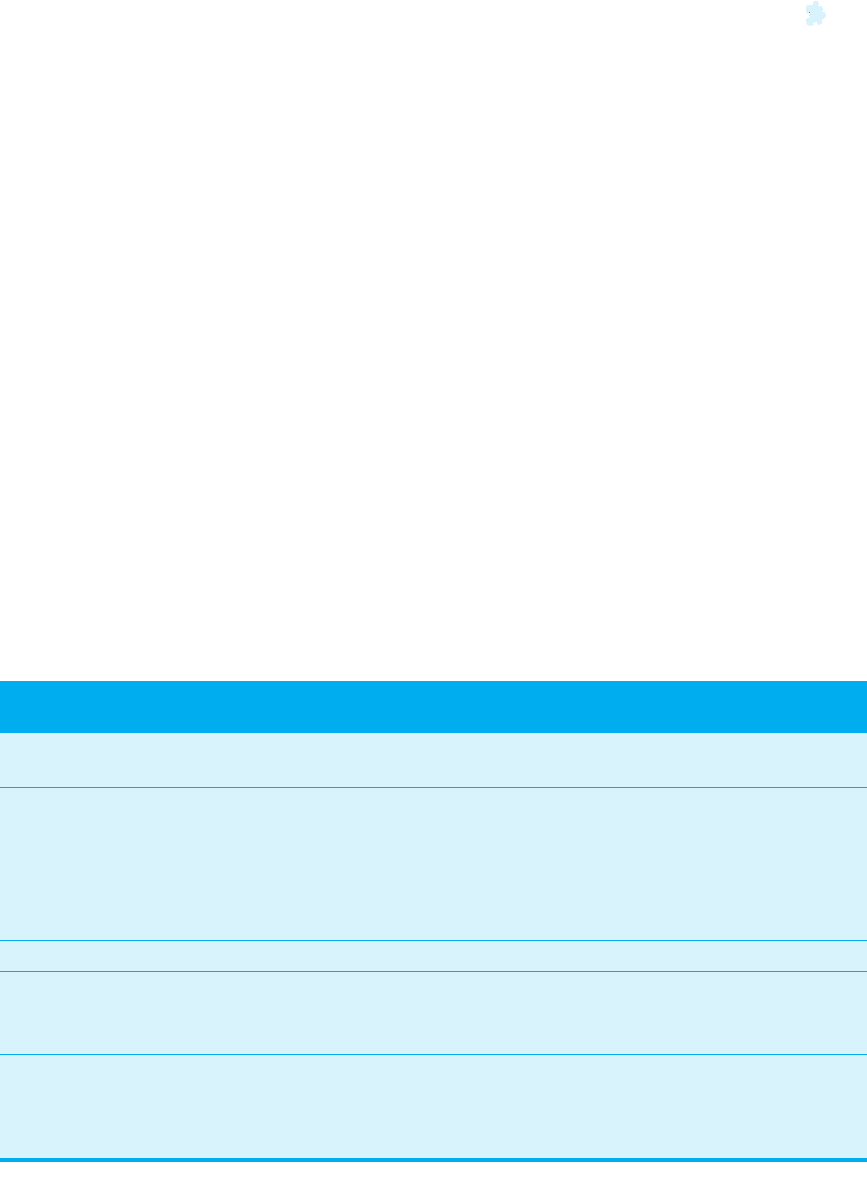

Against this background, Table 12.1 shows that, despite regulatory changes, the

majority of German firms (but also other European firms operating within the Rhineland

model) do not show a preference for market-based transactions. From the table it is clear

that, by the end of the 1990s, the number of German and other European (with the

GLOBALIZATION, CONVERGENCE AND SOCIETAL SPECIFICITY 527

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 527

exception of the UK) corporations that issued tradable shares remains small. In the EU, on

average 64.3 per cent of trading volume is accounted for by 13 firms; for Germany, this is

85.5 per cent by 35 companies; for the UK, in contrast, this is 59.9 per cent by 102 firms

and 51.4 per cent by 113 firms on the NYSE. In general, the concentration of stock

trading in a few companies remains higher in Rhineland-model countries than in Anglo-

Saxon countries. Table 12.2 confirms this picture by showing the differences in the degree

of liquidity and depth of financial markets between the two models. There are still sub-

stantial differences in the ratio of capitalization to GNP between the USA, the UK and

Germany. Even in 2000, German stock markets remained minor players in comparison to

the US and UK markets.

Deregulation of the financial markets in Japan started from the late 1970s.

Important measures were the easing of restrictions in 1979 and 1981 on the issuing of

unsecured straight and convertible bonds and approval in the mid-1980s for banks to

issue convertible bonds (Koen, 2000). After the bad loans crisis of 1996, the Japanese

government implemented further deregulatory measures to foster the restructuring of

the financial sector and to revitalize financial markets.

1

From 1997 onwards, Japan

embarked on a stepwise reform of its general accounting rules, including, among others

things, the adoption of market value reporting, as opposed to the current book value

reporting, for all securities holdings in March 2001, and the adoption of market value

estimation of cross-held shares in March 2002. In 1998, the Foreign Exchange Law was

revised, which resulted in a complete liberalization of cross-border transactions. Foreign

investments into Japan became legally unrestricted, although many informal restrictions

on corporate take-over remain. In 1998, too, a new Financial Holding Company Law

allowed bank holding companies, and, in 1999, brokerage commissions were deregu-

lated. Moreover, rather like the situation in Germany, Japan reformed corporate law in

1997, and introduced stock options, share buybacks and holding companies.

At first glance, it seems that regulatory change in Japan did succeed in creating a

deeper capital market with a high number of listings. Table 12.1 shows that the volume

of share trading in the Japanese capital markets is not concentrated in only a few firms –

as in the other Rhineland-model countries – but instead is spread over a more or less

similar number of firms, as in the USA and the UK. From the late 1970s onwards, large

Japanese corporations started to make greater use of the bond and securities markets,

issuing convertible bonds and other equity-linked debt instruments. The change in the

pattern of corporate financing was accelerated in the mid-1980s, when the Japanese

economy experienced a huge and steady rise in stock prices following the Plaza Accord of

October 1985. Prices on the Tokyo Stock Exchange increased by two and a half times

between 1985 and 1989. Bond issuance in the domestic market, which was mainly com-

posed of convertible bonds, grew sharply from 1986 onwards (Hideaki Miyajima, 1998).

Table 12.2, on the other hand, shows that market capitalization as a percentage of

GDP, while somewhat higher than in Germany, still points to a relatively illiquid and thin

market in comparison with that of the USA and the UK. Related to this conclusion is a

Bank of Japan study, which argues that, to date, the redesigning of Japan’s financial

system in the 1990s has not produced a striking increase in financial transactions via

528 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

1

A complete schedule of financial system reform is available at the Ministry of Finance (MOF) website at

www.mof.go.jp.

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 528

capital markets. According to Japanese flow of funds accounts, the percentage of bank

loans in the financial liabilities of non-financial businesses remains virtually unchanged

from 38.9 per cent at the end of 1990 to 38.8 per cent at the end of 1999. During the

same period, the percentage of shares, equities and securities increased from 38.9 per

cent to 43.1 per cent (Baba and Hisada, 2002).

Moreover, like Germany, Japan has a large SME sector, which is not listed and is

embedded in ‘relational networks’ including local banks. The SME sector accounts for

99.7 per cent of all Japanese firms and contributes to about 80 per cent of employment.

2

In terms of shipment value, the SME manufacturing subsector accounts for about 51 per

cent of the total and nearly 50 per cent of the productivity of its industry as a whole

(Sunday I. Owualah, 1999). In the 1970s, as the large firms tapped alternative sources of

funds in the capital markets, commercial banks began to provide funding to SME

companies. Commercial banks, in conjunction with regional, long-term credit and trust

banks, are now the dominant source of finance for SMEs in Japan. At the end of the

1990s, 77 per cent of financing for plant, equipment and long-term operating funds for

SMEs was provided by commercial, regional and trust banks (Sunday I. Owualah, 1999).

It is even argued that if the relationships between banks and these borrowers were to

weaken, a large number of businesses might be forced into bankruptcy; their performance

will deteriorate if they cannot secure financial assistance (Baba and Hisada, 2002).

Moreover, despite regulatory changes to revitalize the market mechanism, Table 12.3

shows that owner–company relations in the Rhineland model are still most often charac-

terized by one or more large shareholders with a strategic (rather than pure share value

maximization) motivation for ownership. A total of 90 per cent of listed companies in

GLOBALIZATION, CONVERGENCE AND SOCIETAL SPECIFICITY 529

Table 12.1 Concentration in stock exchange trading in international comparison

(in % of trading volume accounted for by largest 5% of corporations)

1988 1993 1998 Number of firms

representing top 5%

Germany

France

Italy

Sweden

Greece

Euro countries average

61

48.8

55.6

28

n.a.

48.4

85.9

61.3

62.5

58.8

n.a.

54.7

85.5

63.4

60

72.7

50.1

64.3

35

37

12

12

11

13

UK n.a. 34.5 59.8 102

Japan

Tokyo

Osaka

55.4

47.4

42.9

62.7

62

79.7

90

63

USA

NYSE

Nasdaq

Amex

n.a.

n.a.

46.1

38.6

64.5

n.a.

51.4

78.8

n.a.

113

275

32

Source: Deutsches Aktieninstitut, DAI Factbook (1999: 6-4-2).

2

Ministry of Public Management, Home Affairs, Posts and Telecommunications, Establishment and Enterprise

Census (1999).

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 529

530 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

Germany have a shareholder with at least a 10 per cent stake in the company. The types

of investor likely to have strategic interests – enterprises and banks – together hold 52 per

cent of shares (or 42 per cent and 10 per cent, respectively). Enterprises generally pursue

strategic business interests. Large German banks have tended to view their shareholdings

as a mechanism for protecting their loans and strengthening their business relationships

with companies, rather than as a direct source of income. The ownership types having

smaller shareholdings – investment funds, pension funds/insurance companies and

households – account for only 35 per cent of total shareholdings of the large German

companies (or 8 per cent, 12 per cent and 15 per cent respectively). The Rhineland system

is thus characterized by concentrated ownership by actors pursuing a mix of financial

and strategic goals (Vitols, 2001: 343). Hence, despite the tendency for the German

financial model to adopt features of the Anglo-Saxon model of finance, a critical distinc-

tion remains: the majority of the German firms continue to have stable, long-term

shareholdership, protecting firms from the short-termism of Anglo-Saxon capitalism.

Source: Rebérioux (2002: 113); Tokyo Stock Exchange Fact Book 2003; Bank of Japan (www.boj.jp).

Table 12.2 National capitalization (market value as a percentage of GDP)

UK USA Germany Japan

1997

161 132 40 53

1998

155 141 48 53

1999

216 191 72 87

2000

187 152 66 66

2001

166 152 61 50

Box 12.1: Resisting the Force of the Anglo-Saxon Model

While there have been moves in the direction of Anglo-Saxon corporate governance by

some German executives, there are still powerful opposing forces. Evidence of these is

the forcing out by his supervisory board of Ulrich Schumacher, the showy, American-

style boss of Infineon, a semiconductor firm, at the beginning of April 2004. Mr

Schumacher was famous for launching his firm’s initial public offering in 2000

dressed as a racing driver. He later irritated trade unionists and worker representatives

with his repeated threats to relocate the Munich-based firm to Switzerland.

By contrast, some top German managers, who in the USA or in the UK might have

been dismissed for poor performance, are still in power because they play the con-

sensus game. A well-known example is Juergen Schrempp, head of loss-making

DaimlerChrysler, who remains in charge, despite DaimlerBenz’s unfortunate merger

with Chrysler. (Economist, 3 April 2004, Kultur clash, 63)

Despite the changes, many fundamental aspects of German company law have been

preserved. Neither the dual-board system nor the principle of employee board represen-

tation were ever seriously questioned. The basic principle of the Joint Stock Company Law

1965 – that neither shareholders, top managers, nor employees should exert unilateral

MG9353 ch12.qxp 10/3/05 8:49 am Page 530