Carla I. Koen. Comparative International Management

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Håkansson (1987, 1989; Håkansson and Johanson, 1993) and his colleagues in

Uppsala have developed an alternative view to the neoclassically orientated concept of

networks as seen from a transaction cost perspective. In their so-called industrial network

theory, which is also referred to as the ‘Swedish network approach’, the basic assumption

is that, over time, the partners in a network involve themselves in a process of social

exchange that gradually builds mutual trust. Instead of the neoclassical point of depar-

ture of transaction cost economics, the Swedish Network Approach takes a more

sociological perspective. Actors are embedded in a societal context of relationships. A

basic assumption in this view is that economic behaviour is path dependent and dynamic.

Relations are viewed as a set of more or less implicit rules, which imply a mutual orienta-

tion of the actors to one another (Håkansson and Johanson, 1993). In other words, in a

(industrial) network there is a web of interdependent activities performed on the basis of

the use of a certain constellation of resources. Industrial networks can therefore be

defined as sets of connected exchange relationships among actors performing industrial

activities (Håkansson and Johanson, 1993).

As the dynamic aspect is a core assumption of this approach, the Swedish network

approach is often used to analyse innovation and cooperation (Lundvall, 1992; Håkan-

sson et al., 1999), in which learning fulfils an important role. The extent to which

learning takes place is highly related to the existence of connections between the relation-

ships. The more a single relationship is part of a larger network, the more a company, on

average, seems to learn from it. Hence, networking increases learning.

A critical perspective of the Swedish network approach

The Swedish network approach, in which embeddedness plays a prominent role, not only

creates the advantages discussed earlier. There are negative elements as well. Maintaining

social ties generates costs, but the social relations of an actor in a network also create obli-

gations towards the other network members (implicit contract). The necessary condition

for a dense social network is trust. A crucial element of trust is reciprocity, and reciprocity

creates obligations. Therefore, the positive side of being embedded in a network is the

advantages of transacting with less transaction cost. The negative side of being a member

– the other side of the trust coin – is the obligational side. These obligations expose an

actor to ‘free riding’ by other members of his network on his own resources. Hence, cosy

inter-group relationships can give rise to the problem of free riding (Portes and Sensen-

brenner, 1993).

The second negative aspect of social capital is the fact that a dense network and the

accompanying community norms can place constraints on individual behaviour.

Membership of a tightly knit or dense social network can subject one to restrictive social

regulations and sanctions, and limit individual action. All kinds of levelling pressures

keep members in the same situation as their peers, and strong collective norms and very

‘solid’ communities may restrict the scope of individuals (Portes and Sensenbrenner,

1993; Meyerson, 1994; Brown, 1998); or, as Woolcock puts it

high levels of social capital can be ‘positive’ in that it gives group members access

to privileged ‘flexible’ resources and psychological support while lowering the risks

of malfeasance and transactions costs, but may be ‘negative’ in that it also places

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 501

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 501

502 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

high particularistic demands on group members, thereby restricting individual

expression and advancement, permits free riding on community resources; and

negates, in those groups with a long history of marginalization through coercive

non-market mechanisms the belief in the possibility of advancement through indi-

vidual effort. (Woolcock, 1998)

Embeddedness may therefore reduce adaptive capacity. This may imply the danger of

lock-in effects and path dependency. These lock-in effects may be strengthened by pro-

cesses of cognitive dissonance in tight groups (Meyerson, 1994; Rabin, 1998).

Individuals that make up a dense network tend to develop a commitment to one another

and to their group. Information that disturbs the consensus of the group’s perception of

reality is likely to be rejected. Woolcock (1998) uses the term amoral familism to describe

the presence of social integration within a group but no linkages outside this group. In his

view, amoral familism undermines the efficiency of all forms of economic exchange by

increasing transaction costs. On the other hand, there is amoral individualism. In this case,

there is no familial or generalized trust at all and only narrow self-interested individuals

exist. Individuals are not embedded in a cohesive social network. A theoretical approach

like transaction cost economics fits very well in this view. In this theory there is no room

for social networks and trust relationships that are based on reciprocity.

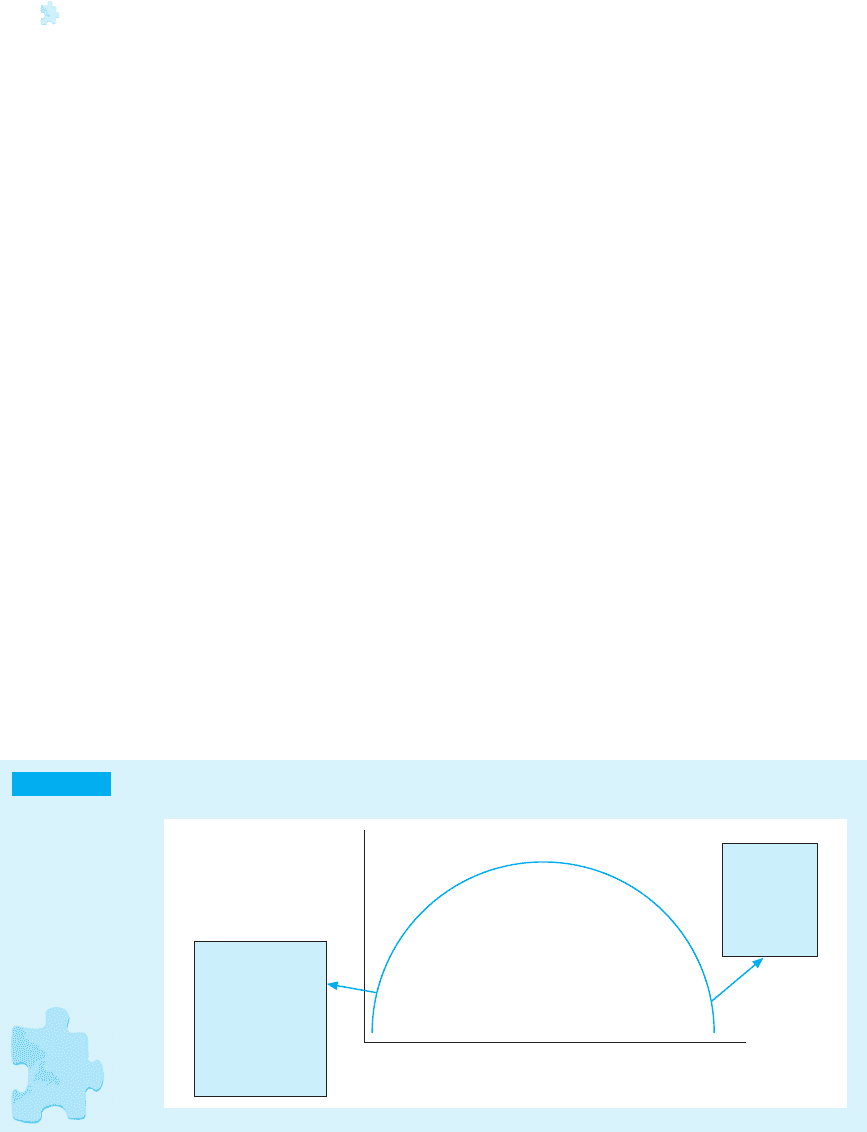

In a study of the apparel industry in New York it has been shown that there is a U-

shaped pattern between the likelihood of failure of a firm and the degree of embed-

dedness, which implies that there is an optimal degree of embeddedness. In a study of the

banking sector, similar results were found (Uzzi, 1996, 1999). Firms are more likely to

secure loans and receive lower interest rates on loans if their network of bank ties has a

mix of embedded ties and arm’s-length ties. Embeddedness seems to yield positive results

up to a certain threshold (see Figure 11.2). Hence, the positive effects of being a member

of a network are the same mechanisms that cause negative effects.

Figure 11.2 Economic success and degree of network closure

Degree of closure of networks

Economic success

Not

embedded

Over-embedded

Isolation (no

trust)

•

No information

exchange

•

Amoral

individualism

•

TCE approach

Lock-in•

Amoral

familism

•

Cognitive

limitation

•

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 502

11.4 From Networks to Clusters

Until now, we have considered networks of economic activity as sets of relationships,

without paying attention to the spatial dimension. Many networks are, indeed, not bound

to a certain location. Just think of the network of shoe manufacturer Nike. At Nike’s

headquarters in Oregon, USA, there are only 900 employees. The rest of this company’s

activities are performed by a close network of suppliers that supply parts of the produc-

tion process (e.g. laces, plastic, heels) from all over the world. Besides such aspatial,

international networks, however, many networks are stuck to a certain place; they are

geographically concentrated and may contribute to a large extent to regional economic

development. Despite all tendencies that point to the decay of distance, in the end, all

economic actions have to be located somewhere. As is the case with networks, several

concepts are used to denote these spatially concentrated networks.

In the next section, some of the most important notions in this respect are discussed.

Subsequently, attention is paid to industrial districts, Porter’s conceptualization of clus-

ters and the innovative milieux. The main message of all these approaches is that

networks of firms that are geographically concentrated may enhance a firm’s competitive

position.

Industrial districts

How firms benefit from geographical clustering

The historical roots of the cluster concept can be found in the literature on ‘industrial dis-

tricts’. The notion of industrial districts goes back to Alfred Marshall, who presented an

economic analysis of the location of industries. In his handbook Principles of Economics

(1890), Marshall explains the development of geographically concentrated clusters, which

he calls ‘industrial districts’, by three factors: specialized labour, dedicated intermediate

inputs and knowledge spillovers. Firms are attracted to a particular location by a labour

market with highly skilled workers. These workers not only possess specialized technical

skills, but also knowledge about people and their activities in the industrial district. Next,

location near a pool of specialized intermediate inputs provides advantages to a firm. In this

way, the firm can obtain equipment, tools, technologies and services from supporting indus-

tries. Moreover, firms can absorb knowledge spillovers in an industrial district, because it is

easier to realize information exchange within the same location than over great distances.

The various benefits of regional concentration are external to the particular firms (‘external

economies’), but internal to the industrial district as a whole. Marshall argues that the

achievement of these benefits depends on the existence of close social relationships between

firms, creating an ‘industrial atmosphere’ within the district. It is clear that such an atmos-

phere favours the learning and innovation process of the firms in the region:

Good work is rightly appreciated, inventions and improvements in machinery, in

processes and the general organization of the business have their merits promptly

discussed: if one man starts a new idea, it is taken up by others and combined with

suggestions of their own; and thus becomes the source of further new ideas.

(Marshall, 1890 (1947 edn): 225)

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 503

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 503

The importance of institutions in industrial districts

Marshall left most of his ideas on industrial districts undeveloped. However, over the last

15 to 20 years, his analysis has played an important role in explaining the economic

success of clusters of small firms in the north of Italy (Pyke, 1995). In the region of Emilia

Romagna, for example, clusters producing machine tools, ceramic tiles, knitting and

footwear can be found. Although around three quarters of the manufacturing workers

are employed in firms with 100 employees, the region has developed from one of the

poorest in Italy to one of the richest in Europe. The success of the clusters in northern

Italy attracted the interest of policy-makers and researchers (see Box 11.1).

Clusters of small firms in other countries were also identified and studied. Well-

known examples of such so-called ‘Marshallian industrial districts’ are Jutland (Denmark),

the Basque country (Spain), Baden-Württemberg (Germany), Toyota City (Japan), Sinos

Valley (Brazil), Daegu (Korea), Silicon Glen (Scotland), Flanders Language Valley

(Belgium) and Silicon Valley (California). In the analysis of these success stories, however,

the researchers place more emphasis on the role of institutions than did Marshall (You

and Wilkinson, 1994). In addition to inter-firm linkages, linkages with institutions, such

as trade associations, research institutes and government agencies, can also be important

factors in explaining the success of industrial districts.

Further research on industrial districts was stimulated by Piore and Sabel. In their

book The Second Industrial Divide (1984), these authors identify fundamental shifts in the

social organization of production and exchange in industrial economies. They argue that,

since the 1970s, the system of mass production has been in crisis. An indication of the

possible end of this period of ‘Fordism’ is the emergence of networks of small firms. The

firms in a network can acquire competitive advantage by using their flexibility to spe-

cialize in niche markets. By cooperating with firms and institutions they can benefit from

cost advantages (‘collaboration economies’). Because cooperation is facilitated by face-to-

face contact and local institutions, the emerging cluster will often be situated in one

region.

Industrial districts: exhibiting a mix of competition and

cooperation

In the 1990s the concept of ‘industrial districts’ benefited from renewed interest thanks

to Krugman’s work (1991). In his contribution, the original ideas of Marshall (1890) are

formalized and brought up to date. Krugman stresses the importance of large-scale firms,

with increasing returns to scale for the emergence of a cluster at a particular location.

These firms will attract supplier firms in order to lower transportation costs and they will

stimulate the development of a local pool of skilled labour around these firms. Through

the exchange of specialized inputs, services and labour, the firms within the cluster learn

from each other continuously. In this way, they can profit through ‘agglomeration

economies’. The author thus views geographic clustering of production as a means for

firms to create sustainable competitive advantage, even in a world economy that is

becoming more and more closely integrated.

Other authors (Best, 1990; You and Wilkinson, 1994) in the 1990s see the key to

understanding the success of an industrial district in the particular mix of competition

504 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 504

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 505

and cooperation among its firms. The firms in an industrial district are specialized, but

complement each other through cooperation in the field of product design or manufac-

turing. At the same time, the firms have to compete in the product market with other firms

supplying similar products and services in the district. The cooperative aspects of inter-

firm relationships help the firms to overcome their disadvantage of small size, while the

competitive aspects provide them with the flexibility that large, integrated firms often do

not possess. A balance between competition and cooperation thus seems crucial for the

functioning of industrial districts. Reviewing the various contributions in the literature,

Rabellotti (1998) concludes that an industrial district can be identified by four stylized facts:

1. proximity – a group of geographically concentrated and specialized small- and

medium-sized enterprises (SMEs)

2. common behaviour – a common behavioural code as the various actors are linked by

the same cultural and social background

3. linkages – a set of linkages between firms based on the exchange of goods, services,

labour and information;

4. institutions – a network of public and private local institutions supporting the various

actors in the cluster.

Box 11.1: Industrial Districts in Northern Italy

Generally, northern Italy is seen as a set of industrial districts par excellence. In con-

trast to the poor south, the Mezzogiorno, the northern part of Italy, has shown high

growth rates based on network structures in such artisan sectors as textiles, clothing,

leather, shoes and ceramics. Santa Croce, for example, a town between Florence and

Pisa, is a breeding place for production and innovation in high-quality leather manu-

facturing (Amin and Thrift, 1994). At the beginning of the 1990s, 300 small- and

medium-sized firms specializing in tanning cooperated with 200 suppliers of raw

leather. Unlike the worldwide leather market, which was gradually approaching matu-

rity, this network proved to be very stable and less vulnerable to cyclical movements. As

reasons for this stability, Amin and Thrift (1994) point to four factors related to the

embeddedness of the leather producers in Santa Croce.

To start with, the agglomeration in the field of leather encouraged the growth of

complementary firms in paint, chemicals and marketing. Next, by cooperating, the

firms were able to yield scale and scope economies, leading to efficiency gains and

process innovations. Furthermore, semi-public organizations, such as local chambers

of commerce, municipal bodies and local training centres, played a supporting role in

Santa Croce. Finally, the close ties between the firms were not only maintained for

economic reasons. The entrepreneurs also met each other in civic associations and at

social occasions throughout the town. Interestingly, it was the Communist Party that

helped to create this atmosphere of collectivity among the local entrepreneurs, thus

also facilitating cooperation in the economic field.

To sum up, regional economic development is not only about economics; local

institutional and cultural factors also play a role.

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 505

Porter’s concept of clusters

How firms derive their competitive advantage from their

embeddedness in clusters

Undoubtedly, Porter’s book, The Competitive Advantage of Nations (1990), has made the

most influential contribution in the field of clustering. He is interested in why only

certain countries generate many firms, which become successful international competi-

tors in one or more industries. For his research on the competitive advantage of nations

Porter has carried out case studies in ten different countries (including Germany, Japan

and the USA). In his analysis, Porter focuses on the individual firm and its position in the

structure of a particular cluster of firms. He suggests that domestic competition contin-

uously creates pressures on firms to innovate. In his view, firms and their linkages of

competition and cooperation with other organizations are the key to the competitive

advantage of these firms, but also to that of the whole nation. Porter argues, then, that

these innovative firms derive competitive advantage from their place within a group of

four sets of factors (determinants), which he calls the ‘diamond’. These factors are as

follows.

1. Factor conditions. This determinant refers to a nation’s position with regard to

factors of production. Competitive advantage is not so much created by basic factors

(cheap unskilled labour, natural resources, etc.), but rather by advanced factors,

which have to be upgraded constantly (e.g. highly skilled labour and a modern

infrastructure).

2. Demand conditions. The nature of home market demand for a product or service influ-

ences the success of a firm in international markets. This depends on the relative size

and growth of the home market, the quality of demand and the presence of mechan-

isms transmitting domestic preferences to foreign markets.

3. Related and supporting industries. These play an important role in the ability of firms to

compete internationally. The existence of industries that provide firms with inputs for

the innovation process stimulates competition and cooperation. Often, the exchange

of these inputs is facilitated by geographical proximity.

4. Firm strategy, structure and rivalry. Differences in national economic structure, organ-

izational culture, institutions (e.g. the capital market) and history contribute to

national competitive success. These conditions determine how firms are created,

organized and managed, as well as how intense the domestic rivalry is.

The determinants of the diamond reinforce each other and together create the

national environment in which firms operate. If this context is dynamic and challenging,

nations will ultimately succeed in one or more industries, since firms are stimulated to

upgrade their advantages over time.

Porter also mentions two additional factors that play a role in national competitive

advantage.

5. Chance events. Chance factors can cause shifts in a nation’s competitive position and

include elements such as major technological changes, shifts in exchange rates or

input prices, and important political developments.

506 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 506

6. The government. Governments play an important role in influencing the dynamics

between the four determinants of the diamond through regulations related to busi-

ness, policies towards the physical and educational infrastructure, and so on.

If all the factors in the diamond are functioning well, the result is a cluster of suc-

cessful firms, both between and within given industries. Originally, Porter defined such a

cluster as follows:

a group of rival firms, suppliers and customers, specialized research centers and

skilled labor pools that are able to draw on common skills, ideas and innovations

generated by the cluster as a whole, which would not be present if the firm operated

in isolation. (Porter, 1990)

Eight years later, Porter seems to have been influenced by ideas originating from the

industrial district approach, when he describes a cluster as:

a geographically proximate group of interconnected companies and associated

institutions in a particular field, linked by commonalities and complementarities.

(Porter, 1998)

The value chain approach to clustering

Porter’s view on clusters is based on his earlier publication, Competitive Advantage (Porter,

1985), in which he uses the concept of ‘value’ to analyse the competitive position of a

firm. Porter argues that a firm can be seen as a value chain – that is, the collection of

activities that are performed to design, produce, market, deliver and support a product

that creates value for the buyers. Each of these activities can contribute to lower costs for

the firm, and creates a basis for product differentiation. The firm’s value chain is

embedded in a larger stream of activities, which is called the ‘value system’. The value

system includes suppliers, delivering products and services to the firm, and various chan-

nels. On its way to the buyer the product passes through the value chains of these

channels, which perform additional activities for the firm (such as distribution activities).

Thus creating and sustaining competitive advantage not only depends on the firm’s

value chain, but also on the question of how the firm fits into the overall value system. As

a result, clusters of competitive industries emerge, providing primary goods (end prod-

ucts), machinery for production, specialized inputs and associated services. According to

Porter, these clusters of related and supporting industries are crucial for competitive

success. An important element of Porter’s value chain approach to clustering is its

emphasis on the end use of products. Consequently, Porter distinguishes 16 possible clus-

ters in terms of the final products that result from them, divided up as follows.

1. Upstream clusters: materials/metals, semiconductors/computers, forest products, and

petroleum/chemicals.

2. Supportive clusters: transportation, energy, office, telecommunications, defence, and

other multiple business services.

3. Downstream clusters: food/beverages, housing/household, leisure, healthcare,

textile/clothing, and personal affairs.

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 507

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 507

Porter considers the performance of products made in a cluster on the world market

as a main indicator of its competitiveness. By including only the more competitive half of

all clusters in a country, one can draft a ‘cluster chart’, which can be used to make a com-

parison of the relative specialization patterns between countries. This relatively simple

idea of clusters has had considerable influence on researchers and policy-makers over the

years. In various countries (the USA, the Netherlands, Italy, Denmark, Sweden and

Finland) the diamond and value chain analysis have been used as a framework to analyse

the competitiveness of (parts of ) the national economy.

How both horizontal and vertical linkages play a role in

clusters

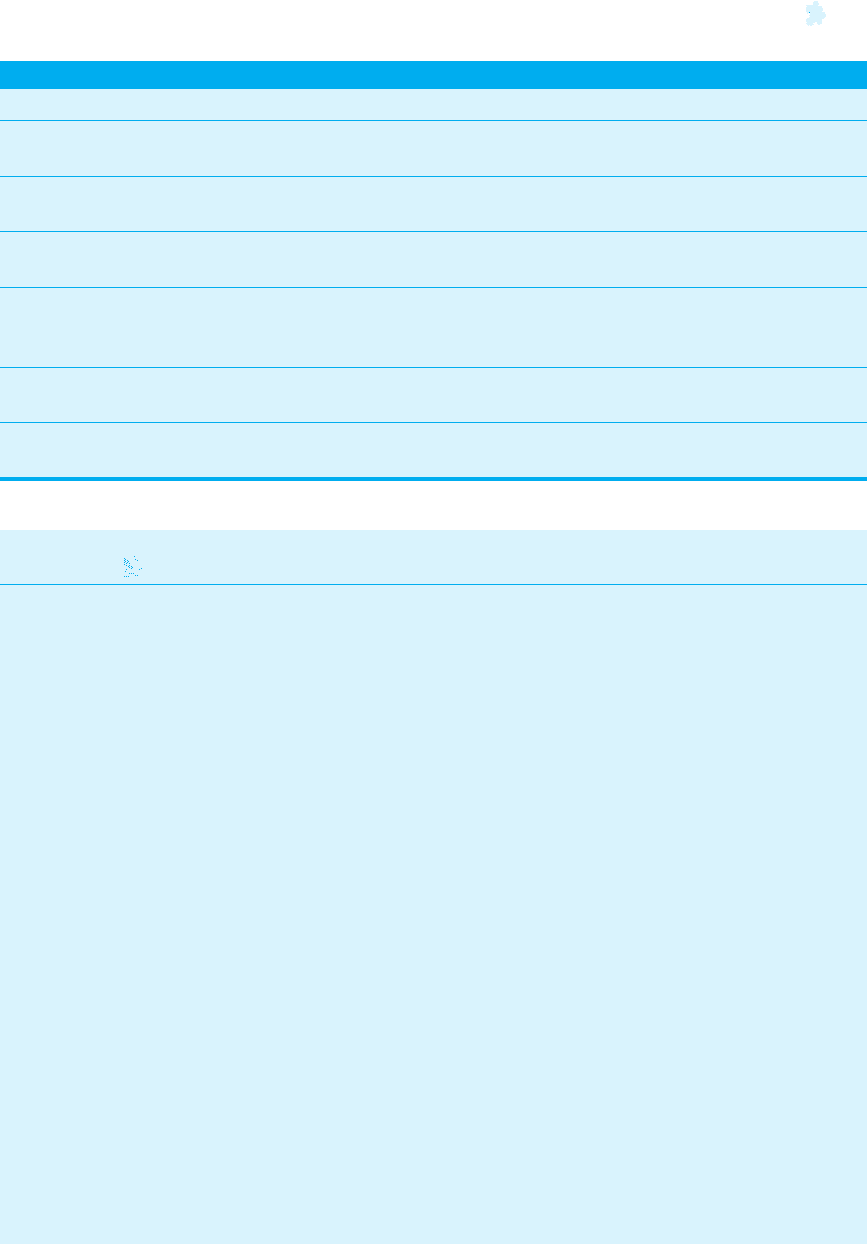

In his recent works Porter (1997, 1998) emphasizes that the cluster approach offers an

alternative to the traditional sectoral approach. The latter approach takes sectors (indus-

tries) as the units of analysis and deals only with horizontal relationships and competitive

interdependence (i.e. relationships between direct competitors in the same product market).

The cluster approach focuses on horizontal relationships too, but also on vertical relation-

ships and synergetic interdependence between suppliers, main producers and users.

Thus the cluster approach cuts through the classical division in sectors and provides a

new way of looking at the economy (see Table 11.1). In addition to his earlier thoughts on

clustering Porter (1998) pays extensive attention to the link between clusters and competi-

tive advantage in his book, On Competition. He argues that clusters stimulate the

competitiveness of firms and nations in three different manners. First, participating in a

cluster allows firms to operate more productively. They have a better access to the means

needed for carrying out their activities – such as technology, information, inputs, customers

and channels – than they would have when operating in isolation. Second, this easier access

will not only enhance the participants’ productivity, but also their ability to innovate. Third,

an existing cluster may provide a sound base for new business formation, as the relationships

and institutions within the cluster will confront entrepreneurs with lower barriers of entry

than elsewhere.

In summary, with the help of different concepts (the diamond, the value chain, the

value system), Porter stresses the importance of clusters in creating and sustaining com-

petitive advantage, not only for individual firms, but also for a nation as a whole.

11.5 Innovative Milieux

Similar to the industrial district approach and Porter’s theory on clustering, the notion of

innovative milieux studies the firm and its partners in their broader environment

(Camagni, 1991; Maillat et al., 1995). As the term innovative milieux suggests, this idea

was identified by authors in France and French-speaking Switzerland. Proponents of this

approach have grouped themselves in GREMI (Groupe de Recherche Europeen sur les

Milieux Innovateurs). The concept of an innovative milieu may, in fact, be seen as the

French variant of the Italian notion of industrial districts. The literature on innovative

milieux has its roots in Perroux’s growth pole approach. Perroux, a French economist,

stressed the asymmetric and cumulative effects innovations may have in space.

508 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 508

NETWORKS AND CLUSTERS OF ECONOMIC ACTIVITY 509

Source: Porter (1997).

Table 11.1 The sectoral approach versus the cluster approach

Sectors Clusters

Focus on one or a few end-product industries Comprise customers, suppliers, service

providers and specialized institutions

Participants are direct or indirect competitors Include related industries sharing technology,

information, inputs, customers and channels

Hesitancy to cooperate with competitors Most participants are not direct competitors,

but share common needs and constraints

Dialogue with governments often aimed at

subsidies, protection and limiting competition

Wide scope for improvements on areas of

common concern, improving productivity and

raising competition

Less pay-off to investments Induce investments by both the private and

the public sectors

Risk of dulling local competition Forums for a more constructive and a more

efficient business–government dialogue

Box 11.2: The Engineering Cluster in Baden-Württemberg

A traditional case of clustering can be found in the German region of Baden-

Württemberg. This region is widely seen as one of the biggest industrial success stories

within Europe over the past 30 years, though it is currently having some problems in

remaining competitive. Still, however, the region is contributing a great deal to main-

taining Germany’s image as a renowned car- and machinery-producing nation. The

region’s success is based on the presence of an engineering cluster that is deeply

embedded in the economy. Leading firms, including Daimler-Benz, Bosch, Audi and

IBM, cooperate fruitfully with small supplier firms (Mittelstand) in the field of automo-

tive, electronics and machine tool engineering. A number of knowledge institutes

(universities, polytechnics, basic and applied research institutes, as well as technology

transfer centres) provide these firms with the latest research findings.

The literature has put forward several factors to explain Baden-Württemberg’s

success. First of all, the importance of history has been emphasized. The tradition of

clustering within Baden-Württemberg can be traced back to the existence of pre-

industrial crafts (Cooke et al., 1995; Hassink, 1997). Thus, there has been a fruitful

base on which to build. Interestingly, this industrial tradition has proved to be advan-

tageous even in modern times. The region’s recent specialization in multimedia has its

roots in the engineering cluster, and Baden-Württemberg has had an active cluster

policy for years. The regional state, often in the form of the former minister-president

Lothar Späth himself, has been proactive in promoting cooperation between ‘state,

industry and science’ for a long time. Many state-sponsored programmes have been

designed to help market parties in the process of clustering. Examples are the forma-

tion of a technology transfer system (‘Steinbeis Stiftung’) and financial aid to firms

wishing to cooperate. As this ‘best practice’ makes clear, the cluster perspective may be

an interesting way of thinking, both for firms and for governments.

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 509

510 COMPARATIVE INTERNATIONAL MANAGEMENT

The GREMI group mainly points to institutional and societal factors in explaining an

innovative milieu’s and its firm’s successful development. According to authors such as

Maillat et al. (1995), organizations operating in innovative milieux differ in three respects.

First, they are relatively autonomous in terms of decision-making and strategy formu-

lation. The interaction between organizations contains an element of both cooperation

and rivalry (cf. the industrial district approach).

Second, the local milieu is characterized by a specific set of material elements (e.g.

physical and telecommunications infrastructure), immaterial factors (knowledge) and

institutional arrangements (e.g. the relevant legal framework). All of these elements

make up a complex of relationships within the innovative milieu. Finally, the interaction

leads to collective learning processes and improves the ability of organizations to cope

with the dynamics of their environment. In sum, in the GREMI literature the innovative

milieu is seen as a local production organization in which firms cooperate collectively in

the field of innovation. Innovation is the result of a joint learning process in which local

actors learn how to transfer material and immaterial assets into products and services

with new characteristics.

Box 11.3: Innovation in the Swiss Watch Industry

A well-known and often cited example of an innovative milieu is the Swiss watch

industry (Camagni, 1991; Weder and Grubel, 1993). In the 1970s this industry met

with severe problems due to increasing competition from cheap Japanese watches.

Based on artisan production dating back to the seventeenth century, the Swiss Jura

d’Arc had developed an international reputation for watch making, machine tools and

micro-electronics (‘Swiss made’ still stands for high quality). Looking back at the econ-

omic history of the Swiss watch history in the 1970s, one may say that the local

parties working in the watch industry more or less became victims of the so-called

‘Icarus paradox’: due to their centuries-long success, they lost the connection to the

worldwide trend of micro-electronics that had also invaded the world of watch manu-

facturing. The result was a delayed reaction to the Japanese threat: most Swiss watch

makers reacted only when the market for traditional watches had already collapsed.

The region more or less fell into the trap of ‘institutional lock-in’ due to over-embedded

relationships between local firms and institutions. Consequently, the number of

workers in the Swiss watch industry decreased from 90,000 in 1970 to 33,000 in

1985.

Interestingly, thanks to the relationships between the local parties in the Jura

d’Arc, the region was able to recover from this crisis. The close ties between local firms

and institutions now proved to be an advantage: they facilitated collective learning and

innovative action. Here, the notion of an innovative milieu really came to the fore.

With the help of local government, business associations and research centres, plans

were developed on how to turn the tide, while building on unique local factors. The

result of this collective search for regional renewal was twofold. On the one hand, in

combating the Japanese competitors the focus still remained partly on producing

expensive quality watches. On the other hand, the region’s industry associations also

decided to develop cheap but trendy watches under the brand name Swatch (Swiss

MG9353 ch11.qxp 10/3/05 8:48 am Page 510