Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

of impurities are coextracted by acetone: sugars and

by product organic acids like oxalic and malic acid.

Therefore, the process involves the fractional precipi-

tation of sugars that precipitate at low pressures

(about 20 bar), the pressure is then increased, and

citric and malic acid precipitate in the same range of

pressures. Oxalic acid is retained in the solution and

precipitated only at very high pressures (higher than

120 bar). Therefore, the purification of citric acid is

not complete: the only residual impurity being malic

acid, which has a very low concentration in the

starting solution. (See Acids: Natural Acids and Acid-

ulants.)

See also: Citrus Fruits: Composition and

Characterization; Essential Oils: Properties and Uses;

Isolation and Production; Soy (Soya) Bean Oil;

Vegetable Oils: Types and Properties; Oil Production and

Processing

Further Reading

Brunner G (1994) Gas Extraction. New York: Steinkopff

Darmstadt Springer.

Bruno TJ and Ely JF (1991) Supercritical Fluid Technology.

Boca Raton, FL: CRC Press.

Clifford T (1999) Fundamentals of Supercritical Fluids.

Oxford: Oxford Science Publications.

King MB and Bott TR (1993) Extraction of Natural Prod-

ucts using Near-critical Solvents. Glasgow, UK: Blackie

Academic & Professional.

Kiran E, Debenedetti PG and Peters CJ (eds) (2000) Super-

critical Fluids: Fundamentals and Applications. Dor-

drecht, The Netherlands: Kluwer Academic.

Luque de Castro MD, Valcarcel M and Tena MT (1994)

Analytical Supercritical Fluid Extraction. Berlin:

Springer Verlag.

McHugh MA and Krukonis VJ (1986) Supercritical Fluids

Extraction: Principles and Practice. Boston, MA: Butter-

worths.

Reverchon E (1997) Review: Supercritical fluid extraction

of essential oils and related materials. Journal of Super-

critical Fluids 10: 1–38.

Reverchon E and Marrone C (2001) Modelling and simula-

tion of the supercritical CO

2

extraction of vegetable oils.

Journal of Supercritical Fluids 19: 161–175.

Smith RM and Hawthorne SB (1997) Supercritical Fluids in

Chromatography and Extraction. Amsterdam: Elsevier

Science.

Sulfur (Sulphur) Dioxide See Preservatives: Classifications and Properties; Food Uses; Analysis

Surface-ripened Cheeses See Cheeses: Mold-ripened Cheeses: Stilton and Related Varieties

Surfactants See Emulsifiers: Organic Emulsifiers; Phosphates as Meat Emulsion Stabilizers; Uses in

Processed Foods

Surgical Nutrition See Burns Patients – Nutritional Management

Swedes See Vegetables of Temperate Climates: Commercial and Dietary Importance; Cabbage and

Related Vegetables; Leaf Vegetables; Oriental Brassicas; Carrot, Parsnip, and Beetroot; Swede, Turnip, and

Radish; Miscellaneous Root Crops; Stem and Other Vegetables

Sweetbread See Offal: Types of Offal

SUPERCRITICAL FLUID EXTRACTION 5687

SWEETENERS

Contents

Intensive

Others

Intensive

A Bassoli and L Merlini, Universita

`

di Milano, Milan,

Italy

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 The sensation derived from tasting a sweet substance

is a pleasant one for most of the contemporary man-

kind. It is debatable whether this is an innate charac-

ter or built on the millenary use of honey and sugar as

foods. Sugar plays an important role in the human

diet, being widely distributed in nature and accounting

for a large portion of total nutrient intake, at least

in the developed countries. The necessity, or interest,

in substituting the whole, or part of, sugar in foods

while maintaining the sweet taste, derived first from

the requirement of reduction of sucrose in the diet of

diabetics, who comprise up to 2% of the world popu-

lation. Later on, from the attempt to avoid risks

connected with obesity or overweight caused by the

excessive caloric intake in developed countries, and to

prevent dental caries. Sweeteners can be used to pro-

duce foods that are sweet yet have no sugar.

0002 A sweetener is a substance that can be added to

foods to confer a sweet taste. Sweeteners belong to

two main classes: intensive and bulk sweeteners. In-

tensive sweeteners are substances so sweet that

minute amounts can substitute substantial amounts

of sucrose, with a greatly reduced caloric intake.

However, this change can create difficulties in the

preparation of traditional sweet foods, such as cakes

or confectionery, in which sugar, often used in large

amounts, confers very important properties besides

sweetness, such as structure and absorbance of

water. This problem can be solved using so-called

bulk sweeteners, which have a chemical structure,

sweetening power, and mechanical and physical prop-

erties very similar to those of sucrose.

0003 From a nutritional point of view, sweeteners are

often classified as caloric, low-caloric, and noncalo-

ric. However, there are no great differences in the

amount of calories produced by the complete con-

sumption of similar amounts of different sweeteners.

Low-caloric sweeteners owe their definition to the

fact that they are not absorbed as much as sugar,

and therefore, while their sweetening potency is

maintained, only a part of their caloric value is util-

ized by the consumer. Similarly, noncaloric sweeten-

ers are so called because they are so much sweeter

than sugar, that only a minute amount is required to

impart the sweetness required, and the energy pro-

duced is negligible. It should be noted that these

definitions are not strict and are used randomly by

different authors.

Intensive Sweeteners

0004The first sweetener to be used was saccharin (q.v.), the

production of which began in 1884, and in the first

half of the last century, production was directed

almost exclusively to diabetics. In the 1950s, the

demand for sweeteners, mostly for soft drinks, led to

the discovery of other sweet compounds, first of all

cyclamates (q.v.). These were used mainly in nonalco-

holic drinks, and in the USA, in 1968, production rose

to 9500 tonnes corresponding to about 300 000

tonnes of sugar. In the meantime, concern about the

possible dangerous consequences of the systematic use

of food additives became increasingly widespread,

with calls for more accurate toxicological tests.

Indeed, the results of studies aiming to demonstrate

the innocuity of cyclamates were used by the Food and

Drug Administration (FDA) to ban cyclamates from

soft drinks in the USA in the 1970s. However, the

controversy surrounding the interpretation of such

studies meant that their use has continued, with

repeated applications to reapprove the use of cycla-

mates, and they are still being used in many other

countries, albeit with restricted daily intake doses.

0005In the last two decades, the market has called for

new sugar substitutes with sensorial properties as

similar as possible to those of sugar, and with unques-

tionable safety. At present, the introduction of a new

sweetener on to the market is regulated by laws or

directives of the authorities (FDA, European Commu-

nity), who require, among other data, a dossier with

acute and long-term toxicity studies. As a consequence

of the different regulatory laws or procedures in dif-

ferent countries, it is possible that the use of a sweet-

ener may not be allowed in all countries, or that the

5688 SWEETENERS/Intensive

procedures to put it into the market are much longer

in one country than in others. For those approved for

use, regulatory authorities, such as the FDA, Scien-

tific Committee for Food of the European Commis-

sion (SCF), or Joint Expert Committee on Food

Additives (JECFA) of the FAO/WHO, have estab-

lished an acceptable daily intake (Table 1).

Design of a New Sweetener

0006 Research on new sweet compounds for use as sugar

substitutes has been constantly growing.

0007 According to Hough, a new sweetener:

1.

0008 should be at least as sweet as sugar, colorless,

odorless, with a pleasant sweet taste, and as simi-

lar to sugar as possible;

2.

0009 should be soluble in water, and chemically and

thermally stable;

3.

0010 should have no toxic effect whatsoever, an

expected metabolism, or be excreted unmodified;

4.

0011 should be easy to produce; if it is a synthetic com-

pound, its purity must be guaranteed; if it is a

natural compound, its sources of supply must be

guaranteed;

5.

0012 should be compatible with production or applica-

tion technologies; and

6.

0013 should be cheaper than those already in use, even

if a better taste or other advantages can counter-

balance a higher cost.

0014 One of the major problems in the research of new

sweet compounds is a lack of information on the

mechanism of sweet-taste perception. Experimental

evidence from biology, chemistry, physiology, psych-

ology, and neurology supports the hypothesis of the

existence of one or more receptor proteins on the taste

buds that should mediate the chemoreception mech-

anism. The first results in cloning candidate genes for

sweet taste receptors appeared in 2001, but the mo-

lecular details of the entire biological process are still

unknown, and so the question of ‘how to design a new

intensive sweetener’ is still open. The rational design

of new molecules generally starts from known sweet

natural compounds or synthetic sweet molecules.

Most of the commercially successful intensive sweet-

eners (such as aspartame and saccharin) have been

discovered by chance and/or designed from a rational

and systematic modification of known molecules. In

this case, the first step is the identification of those

molecular fragments that are important in the recep-

tor–sweetener interaction, the so-called glucophores.

This aim is obtained via a systematic process of struc-

tural modification by synthesis and a critical compari-

son of the structure–activity relationships of the

derivatives obtained. Successful examples of this pro-

cedure are sucralose and neotame.

Perceptual Characteristics of Sweeteners

0015Perceptual characteristics, which include sensory and

hedonic, i.e., pleasant aspects of sweeteners, play a

major role in food selection and intake. Beyond in-

tensity of sweetness, other characteristics, such as the

time–intensity profile, bitterness, other aftertastes

(metallic, sour, etc.), fragrance, ‘body’ (viscosity),

and freshness, influence the perception and therefore

the acceptability and/or the preference for a sweet

material. These characteristics are evaluated by sens-

ory analysis (q.v.), performed by a trained panel of

tasters, following established procedures, and with

statistical treatment of data. In tasting a sweetener,

the form in which it is presented, concentration, tem-

perature, and pH of the solution, are important

factors. Important characteristics are those related

to mouth feel. A sweetener with a negative heat of

solution gives a sensation of cool if tasted as a solid,

that is not given by its aqueous solution. A diluted

solution of an intensive sweetener has a low ‘body,’

which, on the contrary, is perceived when tasting a

more concentrated (and more viscous) solution of a

sugar alcohol, with a sweetness comparable with that

of sucrose. The overall description of the taste quality

of a sweetener is usually reported as a ‘spider web’

diagram (Figure 1), representing the mean scores for

different attributes as determined by the sensory

analysis.

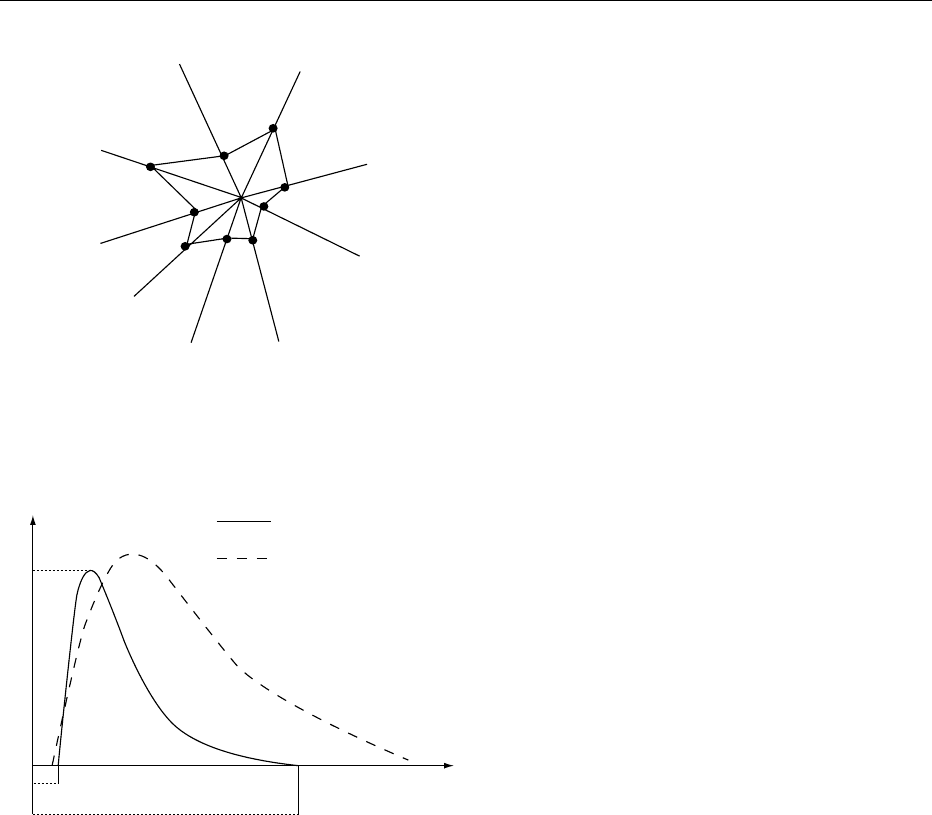

0016The onset of the sweet taste and the change of its

intensity over time, i.e., the temporary profile of a

sweetener, is very important in determining the over-

all quality of the substance. The taste perception is a

time-dependent phenomenon related to the time after

which the sweetness is perceived (lag time), duration,

and speed of the increase and decrease of the stimulus

itself. These parameters are described in a time–inten-

sity profile (Figure 2), which is characteristic and

different for each sweet substance.

0017In the example, the time–intensity profile of

sucrose and an intensive sweetener are compared.

The two substances have similar lag times, and the

sweet taste is immediately perceived; but in sucrose,

the rate of increase and especially the decrease of

the stimulus are higher than in the intensive sweet-

ener. An intensive sweetener usually shows a longer

duration of the stimulus, i.e., a prolonged onset

of the sweet sensation (or lingering) that can some-

times be an undesirable side-effect. The maximum

intensity of the sweet taste (I

max

) is similar, but the

overall effect on the taste of the two substances is

quite different. Each sweetener has its own taste pro-

file, which depends also on the presence of other

sweeteners, taste modifiers, or flavors in the same

mixture.

SWEETENERS/Intensive 5689

tbl0001 Table 1 Characteristics of various sweeteners

Sweetener RS

a

Limitations Status (updated to spring 2001) ADI

b

(mgper

kilogram of

bodyweight)

Notes

Acesulfame K 130–200 At high

concentrations,

may have a slight

aftertaste

Approved by SCF

c

and JECFA

d

.

Approved in more than

90 countries world-wide

15 (JECFA);

9 (SCF)

Flavor enhancer. Good shelf-

life; thermal resistance.

Synergistic with other

sweeteners

Alitame 2000–3000 On long-term

storage, can

impart an off-taste

Approved in Australia, Chile,

Colombia, Indonesia, New

Zealand, Mexico, and the

People’s Republic of China.

Approval is also being sought

in the USA, Europe, and other

countries

0.1–1 Clean sweet taste. Sweetness

profile close to that of sugar.

Heat stability; synergistic

Aspartame

(q.v.)

200 Limited stability

to acidic pH and

high

temperatures

Approved by SCF

c

and JECFA

d

.

Approved by the US FDA

40 Produces phenylalanine during

metabolism: consumption

limited for people suffering

from phenylketonuria.

Synergistic, flavor enhancer

for citrus and other fruits

Cyclamate

(q.v.)

30–50 Approved by SCF

c

and JECFA. A

petition for the reapproval of

cyclamate is under review by

the US FDA

11 (JECFA);

7 (SCF)

Good shelf-life; synergistic;

economic

Neotane 7000–13 000 Slow degradation at

very low pH

Approved by FDA and ANZA

e

6 High quality sweetness, flavor

enhancer, excellent stability

NHDC 400–600 At high

concentrations,

exhibits a long-

lasting sweetness

associated with a

menthol- or

licorice-like

aftertaste

Approved by SCF

c

. Approval for

food use in countries outside

the European Union has been

granted or is being sought

0–5 (SCF) Obtained from bitter flavonoids

in orange peels. Remarkable

synergy with acesulfame and

aspartame. Flavor enhancer,

bitter taste inhibitor

Saccharin

(q.v.)

300–500 Metallic aftertaste Approved by SCF

c

and JECFA

d

.

Approved in more than

90 countries world-wide

5 (JECFA, SCF) The first calorie-free sweetener

discovered in 1879

Stevioside 100–150 Licorice aftertaste Stevia extracts are approved for

food use in several South

American and Asian

countries, but lack approval in

Europe and North America

and at the international level

Not determined Extracted from the leaves of the

Stevia rebaudiana plant

Sucralose 600 Sucralose can

hydrolyze slowly

in solution, under

extreme

conditions of

acidity and

temperature

Sucralose is currently approved

for use in foodstuffs in more

than 35 countries, including

the USA and Japan

0–15 High-quality sweetness, good

water solubility and excellent

stability in a wide range of

processed foods and

beverages

Thaumatin 2000–3000 Delayed perception

of sweetness;

perception lasts a

long time leaving

a licorice-like

aftertaste at high

usage levels

Approved as a sweetener by

SCF

c

and JECFA

d

. Approved

as a flavor enhancer in

Europe. Classified as

generally recognized as safe

by the FDA in the USA

Not specified

(JECFA)

A mixture of three proteins of

molecular weight 22 000,

extracted from the fruit of

West African plant

Thaumatococcus daniellii

a

RS, relative sweetness with respect to sucrose. This value is determined by a sensory analysis of aqueous solutions of sucrose (usually at 3, 5, or 10%

by weight) taken as standard references compared with solutions of the sweetener at different known concentrations.

b

ADI, acceptable daily intake. The ADI is the amount of a food additive, expressed on a body-weight basis, that can be consumed in the diet every day

throughout life without any appreciable health risks. It is in fact a safe intake level.

c

SCF, the Scientific Committee for Food of the European Commission. Reference legislation is contained in the European Parliament and Council Directive

94/35/EC of 30 June 1994 on sweeteners for use in foodstuffs.

d

JECFA, the Joint Expert Committee on Food Additives of the FAO/WHO.

e

ANZA, Food Standards Australia New Zealand.

5690 SWEETENERS/Intensive

Synergy

0018 Many sweeteners show a synergistic effect when used

in mixtures, i.e., the taste intensity of the mixture is

higher than the sum of the intensities of the single

components. This phenomenon is of practical import-

ance, since it offers several advantages. First, the use

of mixtures of intensive sweeteners helps in ap-

proaching the optimal sucrose taste, which can be

mimicked by varying the components’ concentrations

in order to approach the desired time–intensity pro-

file of the mixture. Sweetener mixtures can also have

lower costs, especially if synergy is at play, resulting in

a lower daily consumption of the individual additives

in food. Manufacturers can overcome the limitations

of individual sweeteners by using them in blends;

mixtures of saccharin and cyclamate have been used

in a number of commercial products.

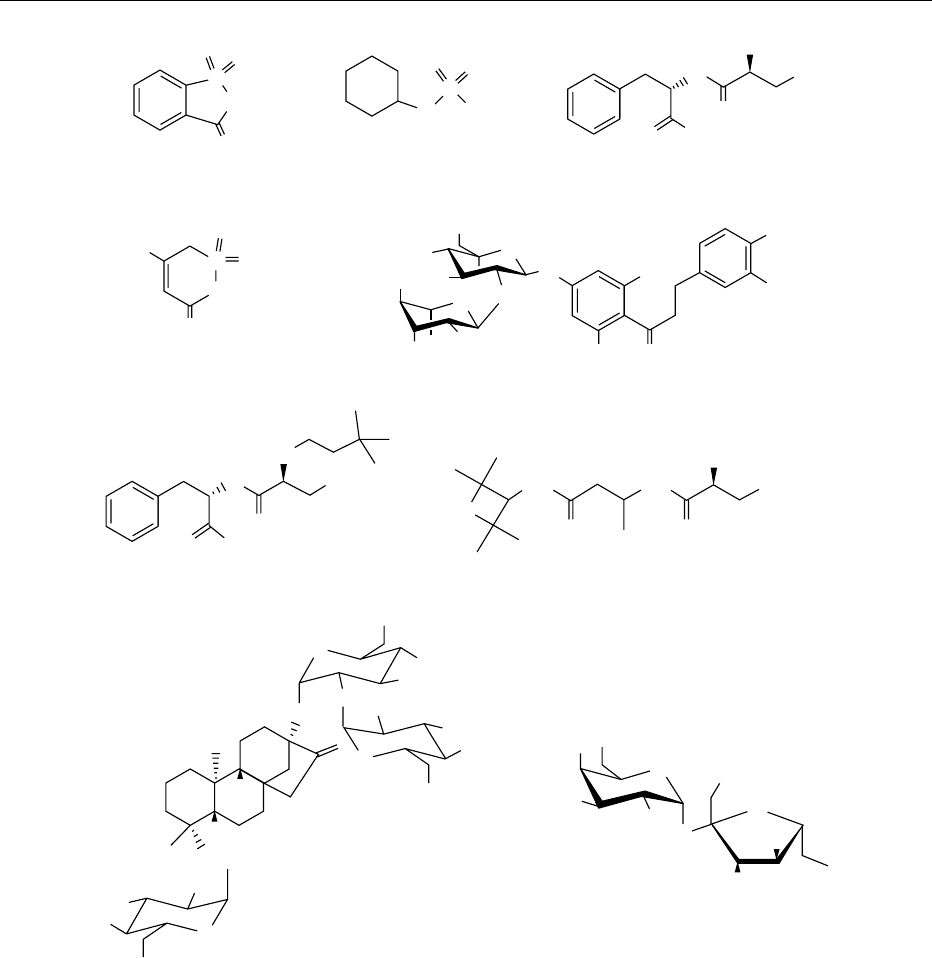

0019Table 1 and Figure 3 provide details and structures,

respectively, of the intensive sweeteners currently

used in many countries.

Acesulfame K

0020Discovered in 1967 by Hoechst, acesulfame K is

structurally related to saccharin. When used in high

concentrations above normal use, it may have a slight

aftertaste.

0021Applications Acesulfame K has a good shelf-life and

is very stable with normal preparation and processing

of foods; it is heat-resistant and therefore suitable for

cooking and baking.

0022Safety Acesulfame K is not metabolized by the body

and is excreted by the kidneys unchanged. A large

number of safety studies have been conducted, and

no adverse effects have been reported.

0023Status Acesulfame K has been approved for a var-

iety of uses in more than 90 countries. In 1998, the

FDA broadened the US approval of acesulfame K to

allow its use in nonalcoholic beverages.

Alitame

0024Discovered by Pfizer Inc., alitame is a high-intensity

sweetener formed from the amino acids l-aspartic

acid and d-alanine, and an amine derived from thie-

tane. The aspartic acid component is metabolized

normally, and alanine amide is not hydrolyzed any

further.

0025Applications Alitame has the potential to be used in

almost all areas where sweeteners are presently used.

It has an excellent stability at high temperatures, and

so it can be used in cooking and baking. During long-

term storage, some soft drinks sweetened with ali-

tame can develop an off-taste.

0026Safety Extensive animal and human studies have

supported the safety of alitame.

0027Status Alitame has been approved for use in a range

of foods and beverages in Australia, Chile, Columbia,

Indonesia, New Zealand, Mexico, and the People’s

Republic of China. Approval is also being sought

(2000) in the USA, UK, Canada, Brazil, Europe, and

other countries.

Aspartame (q.v.)

0028Aspartame, discovered by Nutrasweet in 1965, is the

most commonly used intensive sweetener of the new

generation. The compound is made by coupling two

After sweet

Cooling

Metallic

BitterMint

Liquorice

Body

Init. sweet

Mouthfeel

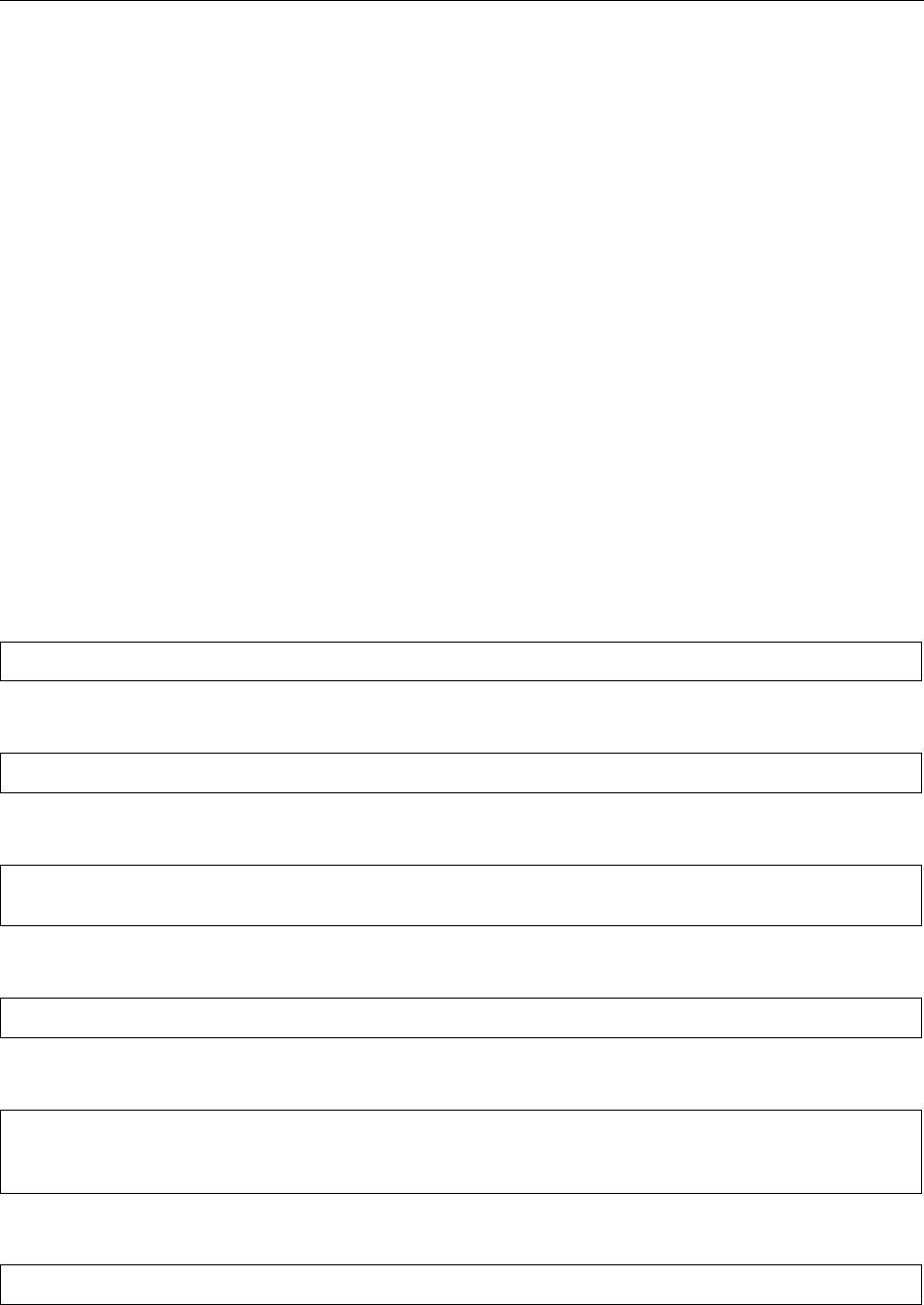

fig0001 Figure 1 A ‘spider web’ representation of some perceptual

characteristics of an intensive sweetener as determined by the

sensory analysis.

Lag-time

Total duration

Time

Intensity

I

max

Sucrose

Intensive sweetener

fig0002 Figure 2 Schematic time–intensity profiles of sucrose and of an

intensive sweetener.

SWEETENERS/Intensive 5691

essential amino acids, aspartic acid and phenylalan-

ine, found naturally in most protein-containing

foods, including meats, dairy products, and vege-

tables. Upon digestion, aspartame breaks down to

phenylalanine, aspartic acid, and a small amount of

methanol, this last in levels that are insignificant

compared with those of many natural foods. Aspar-

tame enhances and intensifies flavors, particularly

citrus and other fruits.

0029 Applications Aspartame is used to sweeten a variety

of foods and beverages, and as a table-top sweetener.

It is currently used in well-known brands of a great

variety of foods and drinks.

0030Safety Aspartame is one of the most thoroughly

tested food ingredients. Aspartame is safe and ap-

proved for people with diabetes, pregnant and nurs-

ing women, and children.

0031Status Aspartame has been approved in more than

90 countries and is widely used throughout Eastern

and Western Europe, the USA, Canada, South Amer-

ica, Australia, and Japan.

S

NH

O

O

S

O

O

O

N

H

ONa

H

N

NH

2

COOH

O

OCH

3

O

S

O

O

O

NK

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OH

OCH

3

O

OH

O

O

HO

HO

O

O

H

N

HN

O

O

OCH

3

COOH

O

O

HN

S

HN

NH

2

COOH

O

O

HO

OH

OH

CI

O

CI

HO

HO

CI

OH

O

OH

HO

HO

H

H

COO

O

O

O

OH

OH

OH

HO

O

OH

OH

OH

Saccharin Cyclamate Aspartame

Acesulfame-K

NHDC

Stevioside Sucralose

Neotame Alitame

fig0003 Figure 3 Structure of the most common sweeteners.

5692 SWEETENERS/Intensive

Cyclamate (q.v.)

0032 Cyclamate was discovered in 1937. It is metabolized

to a limited extent in the gut by some individuals,

shows limited absorption by the body, is excreted

unchanged by the kidneys, is stable at high and low

temperatures, has a good shelf-life and pleasant taste

profile, and is suitable for cooking and baking.

0033 Applications Cyclamate, particularly in combin-

ation with one or more other low-calorie sweeteners,

has a wide range of applications in foods and bever-

ages.

0034 Safety The SCF confirmed the safety of cyclamate in

1994, as did the Cancer Assessment Committee of the

FDA in 1984 and the US National Academy of Sci-

ences in 1985.

0035 Status Cyclamate has been approved in more than

50 countries world-wide. A petition for the reap-

proval of cyclamate is still (as at July 2001) held in

abeyance by the FDA.

Neohesperidinedihydrochalcone (NHDC)

0036 NHDC is a low-calorie sweetener and flavor enhancer

that can be produced by hydrogenation of neohe-

speridine, a flavonoid occurring naturally in bitter

oranges. At high concentrations, NHDC exhibits a

long-lasting sweetness associated with a menthol- or

licorice-like aftertaste. NHDC is not absorbed to any

significant extent, but it is metabolized by the intes-

tinal flora, yielding the same or similar breakdown

products to its naturally occurring analogs.

0037 Applications NHDC is typically used in combin-

ation with other sweeteners, with remarkable syn-

ergistic effects. Even at very low concentrations

(5 p.p.m.), NHDC can still improve the overall flavor

profile and mouth feel of certain foods, acting as

a flavor enhancer and modifier rather than as a

sweetener. It also has bitterness-reducing properties.

NHDC is stable in solid form and in aqueous solu-

tions of pH 1–7. It is heat-stable and therefore can

be used in foods requiring pasteurization or UHT

processes.

0038 Status NHDC is a permitted sweetener in Europe.

Approval for food use outside the European Union

has been granted, or is being sought.

Neotame

0039 It is a derivative of a dipeptide, structurally related to

aspartame. Its relative sweetness is much higher,

being 7000–13 000 times that of sucrose and c.40

times that of aspartame. Neotame has been developed

by Monsanto.

Applications Neotame can be used across many

food categories, including beverages, dairy products,

frozen desserts, baked goods, and gums. It also has

flavor-enhancing properties, especially for mint.

Status In July, 2002, FDA approved neotame for

use as a general-purpose sweetener. Its use is also

permitted in Australia and New Zealand.

Saccharin (q.v.)

0040Discovered in 1879, saccharin has been used commer-

cially to sweeten foods and beverages since the turn of

the twentieth century. It is absorbed slowly, not me-

tabolized, rapidly excreted unchanged by the kidneys,

highly stable with a long shelf-life, suitable for

cooking and baking, does not promote tooth decay,

and is suitable for diabetics.

0041Applications Saccharin has the widest range of ap-

plications and is used in a great variety of foods.

0042Safety Saccharin has a history of a century of safe

human use and is probably the most thoroughly re-

searched of all food additives. Its safety was ques-

tioned in a 1977 Canadian study that found bladder

tumors in male rats, albeit given unrealistically high

doses. All scientific research conducted since then has

shown that this effect is only seen in male rats at

extremely high doses and has supported the safety of

saccharin for human use at the levels currently con-

sumed. Several human studies have shown no overall

association between saccharin consumption and

cancer incidence.

0043Status Saccharin has been approved in more than 90

countries. In the USA, the FDA proposed a ban on

saccharin in 1977, on the basis of the aforementioned

high-dose rat studies. The proposed ban was formally

withdrawn in 1991, but saccharin and foods and

drinks containing saccharin were still required to

carry a warning label. In 2000, legislation gave sac-

charin a clean bill of health and removed the label.

Stevioside

0044Stevioside is extracted from the leaves of Stevia

rebaudiana Bertoni, a plant growing in South America

and several Asian countries. Stevioside is a glycoside

consisting of the aglycone steviol (ent-13-hydroxy-

kaur-16-en-19-oic acid) and three glucose molecules.

The sweetness of stevioside is accompanied by a

licorice-like aftertaste.

0045Applications Leaves of the stevia plant have been

used for centuries in Brazil and Paraguay to sweeten

SWEETENERS/Intensive 5693

foods and beverages. Stevioside can be used in soft

drinks, Japanese-style vegetable products, table-top

sweeteners, confectionery, fruit products and sea-

food, and in some countries as stevioside-rich Stevia

extracts.

0046 Safety and status Stevia extracts have been ap-

proved for food use in several South American and

Asian countries but lack approval in Europe and

North America and on an international level. Safety

studies on stevioside and Stevia rebaudiana have not

been accepted internationally, owing to the lack of

generally accepted specifications. In 1999, the SCF

reiterated the opinion that ‘‘stevioside is not ac-

ceptable as a sweetener on the presently available

data.’’ The JECFA reviewed stevioside in 1998

but could not quantify an acceptable daily intake

(ADI) because of inadequate data on the com-

position and safety of stevioside. In 2000, the Euro-

pean Commission refused a request for marketing

authorization for Stevia rebaudiana plants and

dried leaves. Stevioside, as a sweetener, is not permit-

ted in the USA and may not be used or marketed in

Europe.

Sucralose

0047 Sucralose is the common name for 4,1

0

,6

0

-trichloro-

galactosucrose, a high-intensity sweetener derived

from ordinary sugar, developed jointly by McNeil

Specialty Products and Tate & Lyle. Sucralose is not

metabolized.

0048 Applications Sucralose has a high-quality sweet-

ness, good water solubility, and excellent stability in

a wide range of processed foods and beverages. Like

sugar, sucralose hydrolyzes in solution, but only over

an extended period of time under extreme conditions

of acidity and temperature.

0049 Safety Extensive studies have shown that it is safe

for human consumption.

0050 Status Sucralose is currently approved for use in

foodstuffs in more than 35 countries.

Thaumatin

0051 Thaumatin is a low-calorie protein sweetener and

flavor modifier extracted from Katemfe, the fruit of

the West African plant Thaumatococcus daniellii,and

is totally natural with an intense sweetness. A limita-

tion of thaumatin is its delayed perception of sweet-

ness, but perception lasts a long time, leaving a

licorice-like aftertaste at high usage levels. It is me-

tabolized by the body like any other dietary protein.

0052Applications Thaumatin is stable in freeze-dried

form and is soluble in water and aqueous alcohol. It

is heat- and pH-stable and synergistic when combined

with other low-calorie sweeteners. Thaumatin has a

wide range of applications in food and drinks and is

particularly effective for its flavoring properties and

because it adds mouth feel.

0053Safety A large number of animal and human studies

have been conducted, showing no adverse reactions.

Thaumatin is classified as generally recognized as safe

by the FDA. The JECFA gave thaumatin an ADI of

‘not specified.’

0054Status Thaumatin is a permitted sweetener and has

been approved in all applications in the European

Community as a ‘flavor preparation.’ Similar ap-

proval exists in Switzerland, the USA, Canada, Israel,

Mexico, Japan, Hong Kong, Korea, Taiwan, Viet-

nam, Australia, New Zealand, and South Africa,

and further approval is being sought elsewhere.

Uses

0055Food Intensive sweeteners have several practical ap-

plications. Their main use is in food, where they are

used as additives in several products: table-top sweet-

eners, carbonated beverages (soft drinks), noncarbo-

nated beverages (e.g., coffee drinks, alcoholic drinks,

cider, juices, fruit nectars, shakes, ice tea, instant

beverages), dairy products (yogurt, icecream), des-

serts (puddings, jellies, gelatins, flans), marmalade

and jams, chocolate, fruit preserves, fruit spreads,

baked goods (confectionery, biscuits, breakfast

cereals), chewing gum, pickled vegetables, marinated

fish, savories, sauces, and salad dressings.

0056They are also used in the preparation of dietetic

products or functional foods such as vitamin- and

mineral-fortified products, sport drinks, and low-fat

products.

0057Pharmaceuticals and dental decay prevention In

pharmaceuticals, sweeteners are used as additives in

drugs for oral administration, especially to mask the

bitter or unpleasant taste of certain active ingredients.

They are widely used in the preparation of toothpaste

and mouthwash, for improving taste and preventing

dental decay. In fact, dental caries is the result of the

interaction of sucrose or other carbohydrates with

oral bacteria, leading primarily to dental plaque for-

mation and secondarily to tooth decay, as a result of

the alterations of dentin caused by acidic fermenta-

tion end products and inflammatory processes in-

duced by bacterial toxins.

0058The potentiality of alternative sweeteners to reduce

dental caries has attracted much interest and many

5694 SWEETENERS/Intensive

studies. All the intensive sweeteners and sugar alco-

hols (q.v.), such as xylitol, sorbitol, and mannitol, are

noncariogenic, since they are not fermented by oral

bacteria.

Economics

0059 The world market for sweeteners has tended to in-

crease broadly in line with the world economy. The

average growth rate in the 1990s was around 2%.

The world consumption of intensive sweeteners

reached 12 million tonnes of sugar equivalents in

1997, with a share of the total sweeteners market of

c. 9%. Asia accounts for 50–55% of the total, with

the rest being shared almost equally between the

Americas and Europe. More than 70% of the market

by quantity (sugar equivalents) is represented by sac-

charin, aspartame having 18% and cyclamates 5%,

whereas if the consumption is measured by value,

aspartame accounts for 62%, saccharin 17%, cycla-

mates 5%, and others 16%. The high share of sac-

charin is due to its cheapness, making it suitable for

use in many applications where only a generic sweet-

ener is required, and for nonfood use, such as

pharmaceuticals, animal feed, and toothpaste. An-

other reason is its stability under a wide variety of

conditions, together with a high-quality sweetness.

All this explains why it has a high share (90% or

more) of the Asian market, whereas aspartame is

mostly used in North America, followed by Europe.

As for other, recently introduced, intensive sweeten-

ers, the use of acesulfame-K is increasing, especially in

blends for soft drinks, whereas the natural compound

stevioside is mostly used in Asia.

Bulk Sweeteners

0060 In sweet foods, sucrose provides not only sweetness

but also, in many cases, structure, weight, and

volume. This ‘bulk’ effect must be maintained in

sugarless products to insure that those properties

make the product acceptable to the consumer and to

maximize the shelf-life. Moreover, the substitution of

sugar must minimize the changes in the technological

processes of production. In products where this bulk

effect cannot be provided only by water (drinks) or

partially by air (e.g., in icecreams), such as confec-

tionery, chocolates, hard and soft candies, jellies,

chewing gums, drage

´

es, and jams, the so-called bulk

sweeteners can be used. The most important of these

are glucose, fructose, lactose, galactose, maltose

(q.v.), and sugar alcohols (q.v.), these last obtained

by hydrogenation of carbohydrates. They should

have a relative sweetness and rheological properties

at least as good as that of sugar. (See Sugar Alcohols.)

See also: Acesulfame/Acesulphame; Aspartame;

Cyclamates; Isomalt; Saccharin; Sensory Evaluation:

Sensory Characteristics of Human Foods; Taste;

Sucrose: Properties and Determination; Sugar: Refining

of Sugarbeet and Sugarcane; Sugar Alcohols

Further Reading

Corti A (ed.) (1999) Low-calorie Sweeteners Present and

Future: World Conference on Low-calorie Sweeteners.

Basel: Karger.

Gilbertson TA and Kinnamon SC (1996) Making sense of

chemicals. Chemistry and Biology 3: 233.

Grenby TH (ed.) (1987) Development in Sweeteners, vols.

1–3. London: Elsevier Applied Science.

Grenby TH (ed.) (1989) Progress in Sweeteners. London:

Elsevier Applied Science.

Guesry PR and Secre

´

tin M (1991) Sugars and non-nutritive

sweeteners. In: Gracey M, Kretchmer N and Rossi E

(eds) Sugar in Nutrition. Nestle

´

Nutrition Workshop

Series, vol. 25, pp. 33–53. New York: Raven Press.

Hough L (ed.) (1997) Plenary Lectures from the Jerusalem

International Symposium on Sweeteners. Pure & Ap-

plied Chemistry 69: 655–727.

Laing GD and Jinks A (1996) Flavour perception mechan-

isms. Trends in Food Science and Technology 7: 387–

388.

Mathlouthi M, Kanters A and Birch GG (eds) (1993) Sweet

Taste Chemoreception. London: Elsevier Applied Sci-

ence.

O’Brien L and Gelardi RC (eds) (1991) Alternative Sweet-

eners. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Schiffman SS (1991) Receptors and transduction mechan-

isms for sweet taste: an overview. In: Gracey M, Kretch-

mer N and Rossi E (eds) Sugar in Nutrition. Nestle

´

Nutrition Workshop Series, vol. 25, pp. 55–67. New

York: Raven Press.

Shallenberger RS (1994) Taste Chemistry. London: Blackie

& Hall.

Van der Wel H, Van der Heijden A and Peer HG (1997)

Sweeteners. Food Reviews International 3: 193–268.

Walters DE, Orthoefer FT and DuBois G (eds) (1991)

Sweeteners: Discovery, Molecular Design and Chemor-

eception. Washington, DC: American Chemical Society.

Others

M B A Glo

´

ria, Federal University of Minas Gerais,

Belo Horizonte, Minas Gerais, Brazil

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Sweetness is one of the most important taste sensa-

tions for humans. Sucrose has been widely used for its

SWEETENERS/Others 5695

sweetness, functional properties such as texture and

mouth feel, and as a bulking agent and preservative.

However, the special dietary needs of diabetics and

the health concerns about obesity and dental caries

have prompted considerable efforts for the develop-

ment of alternative sweeteners.

0002 Sweeteners are widely used in the food, beverage,

confectionery, and pharmaceutical industries through-

out the world. Because of high consumer demand and

acceptance of low-calorie products, the market of arti-

ficially sweetened foods has increased significantly

and will continue to grow.

0003 Sweeteners can be classified into two categories,

bulk and intense. The bulk sweeteners are used as

sweeteners and as bulking agents and can have a

preservative and bodying effect. They are metabol-

ized by the body and provide calories and include

glucose, fructose, maltose, hydrolyzed products

from starch and sugar alcohols. They vary in sweet-

ness over a narrow range, from 0.3 to 1.2 times the

sweetness of sucrose. Bulk sweeteners are permitted

in a number of specified foodstuffs at quantum satis –

as much as needed.

0004 The intense sweeteners have a sweet taste but

are effectively noncaloric. They can be natural or

synthetic compounds, and they are intensely sweet,

ranging from 30 to 3000 times the sweetness of

sucrose, so the concentrations used for normal sweet-

ness are very low. This category includes saccharin,

cyclamate, acesulfame-K, aspartame, alitame, dulcin,

sucralose, neohesperidin dihydrochalcone, glycyrrhi-

zin, stevia sweeteners, and thaumatin. The first four

compounds are the main sweeteners consumed and

are presented in other sections. Dulcin (4-ethoxyphe-

nylurea, C

9

H

12

N

2

O

2

, MW 180.20) was synthesized

by Berlinblau in 1884. It is 70–350 times sweeter than

sucrose. However, it should not be used as a food

additive, since it has been reported to cause cancer

in laboratory animals. The purpose of this chapter is

to provide general information on the other intense

sweeteners.

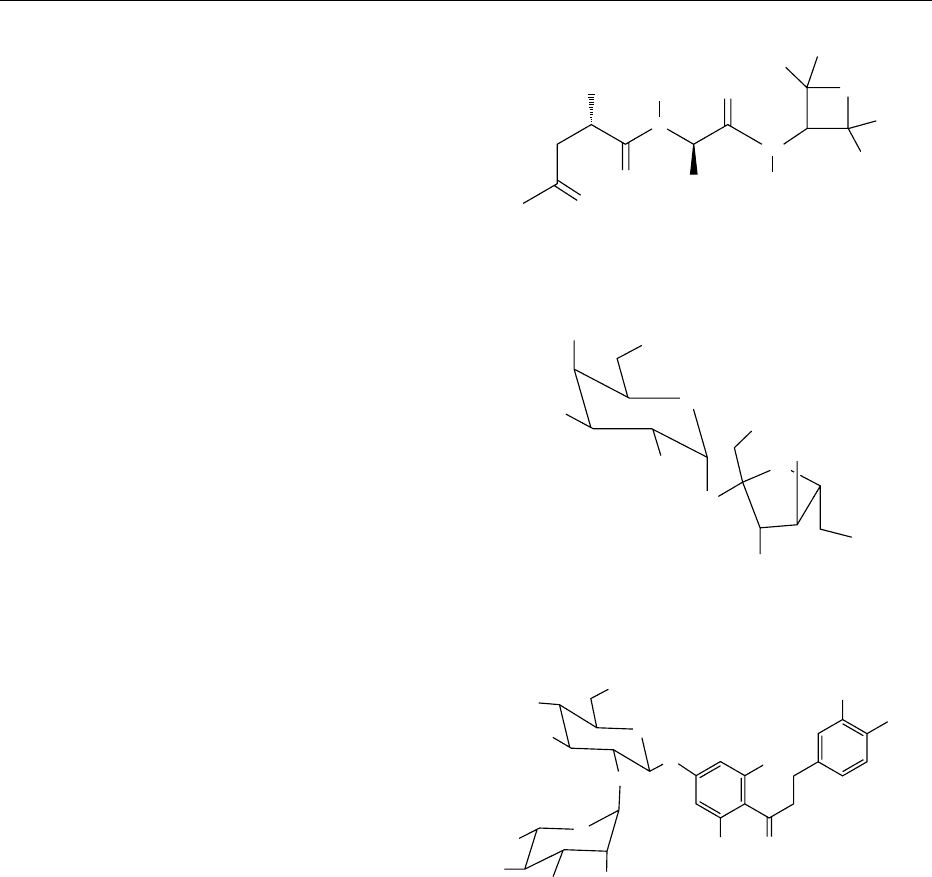

0005 The sweeteners have different chemical structures

(Figures 1–5) and, therefore, diverse properties

(Table 1). Maximum levels have been established

for intense sweeteners in different food categories,

depending on the legislation in a particular country.

Alitame

0006 Alitame [l-a-aspartyl-N-(2,2,4,4-tetramethyl-3-thio-

ethanyl)-d-alaninamide] is an amino acid-based

sweetener (Figure 1) developed by Pfizer Central Re-

search from l-aspartic acid, d-alanine, and 2,2,4,4-

tetraethylthioethanyl amine. A terminal amide group

instead of the methyl ester constituent of aspartame

was used to improve the hydrolytic stability. The

incorporation of d-alanine as a second amino acid

in place of l-phenylalanine has resulted in optimum

sweetness. The increased steric and lipophilic bulk on

a small ring with a sulfur derivative has provided a

very sweet product and good taste qualities.

0007The formula of alitame is C

14

H

25

O

4

N

3

S, with a

molecular weight of 331.06. It is produced under the

brand name Aclame

1

. It is a crystalline, odorless, and

nonhygroscopic powder, with a good solubility in

most polar solvents such as water (130 g l

1

at pH

5.6) and alcohol (Table 1). Alitame is 2000 times

sweeter than sucrose, 12 times sweeter than aspar-

tame and six times sweeter than saccharin. It has a

NH

2

H

O

S

N

N

O

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

H

HO

O

H

3

C

fig0001Figure 1 Chemical structure of alitame.

Cl

Cl

Cl

OH

OH

OH

OH

O

O

O

HO

fig0002Figure 2 Chemical structure of sucralose.

OH

OH

OH

OH

OCH

3

OH

OH

HO

HO

HO

H

3

C

O

O

O

O

O

fig0003Figure 3 Chemical structure of neohesperidin dihydrochal-

cone.

5696 SWEETENERS/Others