Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

swimming in malacostracans. In this group the ter-

minal somite bearing the anus forms a flattened

telson, and the last pair of abdominal segments are

modified to form uropods; together with the telson;

these form a tail fan used in swimming.

0014 The gut is divided into a chitin-lined fore- and

hindgut and a midgut lined with endoderm. The fore-

gut esophagus leads to a stomach which is often

subdivided into cardiac and pyloric regions in mala-

costracans. The midgut forms an intestine of variable

length and bears the digestive cecae or hepato-

pancreas, emptying into the pyloric chamber of the

stomach. The hindgut is usually short, absorptive in

function, and leads to the anus. In crabs and lobsters,

mechanical breakdown of food in the gastric cham-

bers of the stomach is performed by heavily sclero-

tized teeth which form a grinding gastric mill; in

shrimps this structure may be absent and breakdown

is solely by enzymes secreted from the hepato-

pancreas. The products of digestion are absorbed

by cells in the fine tubules of the hepatopancreas,

or cells lining the midgut trunk, where further

intracellular digestion occurs. In some groups, ex-

pelled fecal material is sheathed in a peritrophic mem-

brane.

0015 The circulatory system is comprised of a dorsal

muscular heart with ostia or pores to draw in blood

from the pericardial cavity. In advanced malacostra-

cans the heart has a series of blood vessels insuring

that blood flows to body organs and to the gills

(Figure 1). Return to the heart is via pools or the

hemocoel, although active crustaceans may have a

primitive venous system to return the blood to the

pericardial cavity. Gaseous exchange in large,

advanced crustaceans is via gills, which arise as

branches from the base of the thoracic limbs. The

gills are modified in various ways to provide a large

surface area of thin, permeable cuticle, and in deca-

pods are protected under the carapace in branchial

chambers through which ventilating currents of water

are drawn.

0016Excretion is in the form of ammonia, which is

released across gill surfaces and via nephridia in max-

illary or, in most malacostracans, antennal glands

(Figure 1). These glands are also active in osmoregu-

lation, as are the gill surfaces. The crustacean cuticle,

unlike the waxy insect cuticle, is largely permeable,

and imposes severe constraints upon ionic regulation;

hence few crustaceans are found away from water.

0017The crustacean brain is composed of three fused

ganglia – two anterior dorsal supraesophageal

ganglia and a third which forms a pair of circumen-

teric connectives extending round the esophagus to a

subesophageal ganglion linked to the ventral nerve

cord. This cord bears paired segmental body ganglia.

The optic and antennulary nerves run to the supra-

esophageal ganglia, and the subesophageal ganglia

often become a large, fused mass serving the nerves

to the mandibles, maxillules, maxillae, and maxilli-

peds. In crabs all the thoracic ganglia fuse to form a

large ventral nerve plate. Sensory systems are well

developed, despite the exoskeleton, and take the

form of innervated setae responding to touch or cur-

rents, whilst others, such as esthetascs, detect chem-

icals or gradients in attractants emanating from food.

0018Crustaceans are well adapted to detect light, and

photoreceptors range from the simple larval naupliar

eye, responding to light direction and intensity, to the

tbl0001 Table 1 Pennant (1771) classification of phylum, subphylum or superclass Crustacea utilized directly for human nutrition

Class Maxillopoda

Subclass Cirripedia

Order Thoracica Stalked barnacles, e.g., Pollicipes

Subclass Copepoda

Order Calanoida Copepods, e.g., Calanus plumchrus

Class Malacostraca

Subclass Hoplocarida

Order Stomatopoda Mantis shrimp (Squilla mantis)

Subclass Eumalacostraca

Superorder Peracarida

Order Mysidacea Possum shrimp (Neomysis intermedia)

Superorder Eucarida

Order Euphausiacea Krill, e.g., Euphausia superba

Order Decapoda

Suborder Dendrobranchiata Penaeid and sergestid shrimps, e.g., Penaeus, Sergestes

Suborder Pleocyemata

Infraorder Caridea Caridean and procaridean shrimps, e.g., Macrobrachium, Palaemon

Infraorder Astacidea Crayfish and chelate lobsters, e.g., Astacus, Homarus, Nephrops

Infraorder Palinura Palinurid, spiny, and slipper lobsters, e.g., Panulirus, Palinurus,Thenus, Scyllarides

Infraorder Anomura Galatheid crabs, king crabs, e.g., Paralithodes, Pleuroncodes

Infraorder Brachyura Crabs, e.g., Cancer, Scylla, Callinectes, Maia

SHELLFISH/Characteristics of Crustacea 5207

(a) (b)

(c)

(d)

(e)

(f)

(g)

sog

fg

aa

cs

h

ps

hg

pa

hp

vc

o

mg

sg

ag

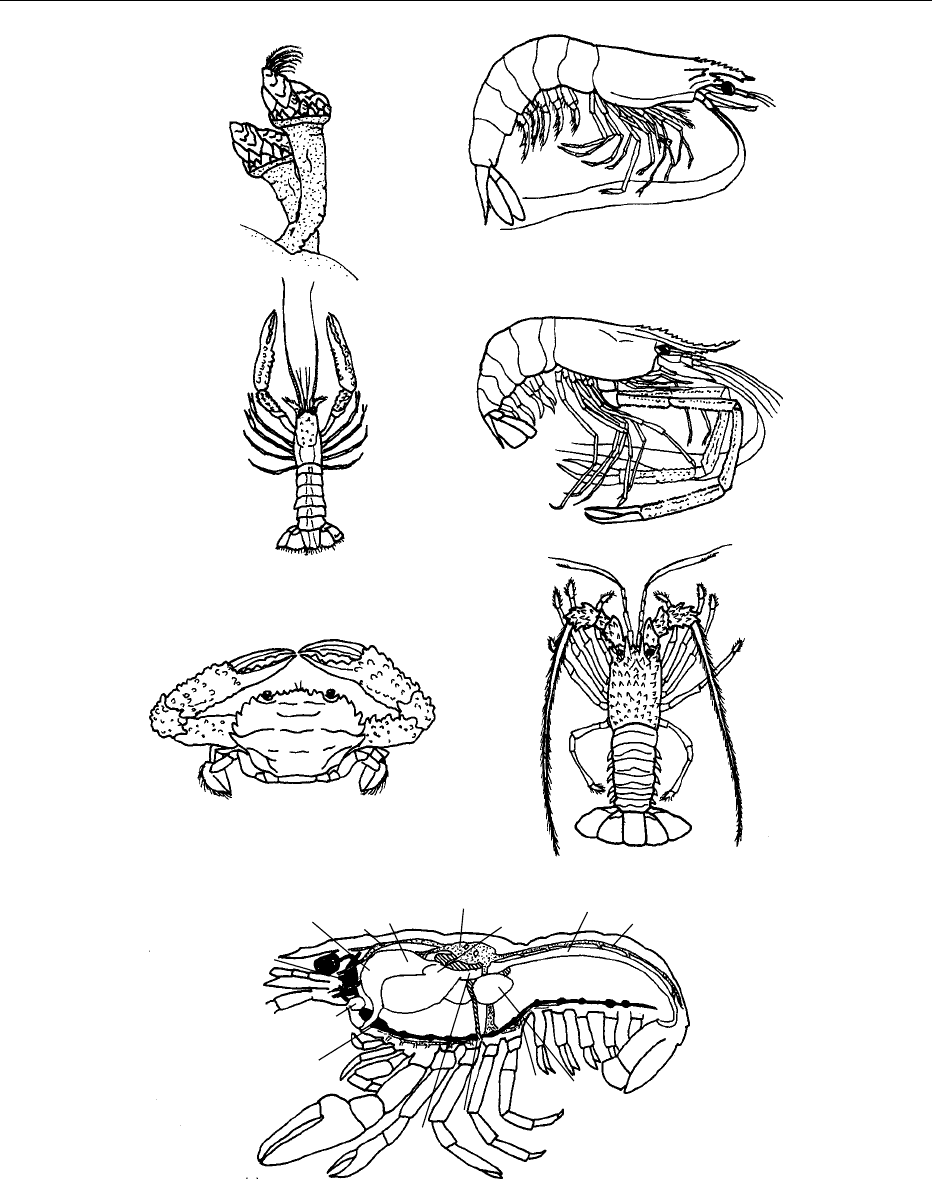

fig0001 Figure 1 (a) Stalked barnacle (Pollicipes sp.); (b) Penaeus shrimp; (c) (Macrobracium Norway lobster (Nephrops sp.); (d) caridean

shrimp (Macrobracium sp.); (e) swimming crab (Charybdis sp.); (f) spiny lobster (Panuliris sp.); (g) fresh-water crayfish (Astacus sp.). sog,

supraesophageal ganglia; fg, foregut; aa, anterior aorta; cs, cardiac stomach; h, heart; ps, pyloric stomach; hg, hindgut; pa, posterior

aorta; hp, hepatopancreas; vc, ventral nerve cord; o, oviduct; mg, midgut; sg, subesophageal ganglion; ag, antennal gland. Repro-

duced from Shellfish, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993,

Academic Press.

5208 SHELLFISH/Characteristics of Crustacea

stalked, multifaceted compound eye found in deca-

pods. This is capable of discerning shapes, patterns,

and movement and at least some have color vision.

Molting, chromatophore activity, tidal and daily

locomotor rhythms, and aspects of reproduction are

under hormonal and neurosecretory control, but an

understanding of the mechanisms of this control is

still at an early stage.

tbl0002 Table 2 Composition of commercial crustaceans (all figures are per 100 g of raw material, except Homarus, which is boiled)

Energy

(kcal)

Carbohydrate

(g)

Protein

(g)

To t a l f a t

(g)

Fattyacids Cholesterol

(mg)

Saturated

(g)

Mono-

unsaturated (g)

Poly-

unsaturated (g)

n-3 (g)

Crab (mixed) 74–95 0–2.2 15–18 0.8–1.9 0.16–0.17 0.22 0.4–0.5 0.38–0.44 60–78

Penaeid shrimp 87–100 0–2.7 17–22 0.4–0.8 0.11–0.2 0.05–0.15 0.09–0.49 0.07–0.34 96

Panulirid lobster 100 1.7 19.2 1.2 0.14 0.14 0.59 0.27 106

Homarid lobster 93 5.4 20.5 0.6 0.08 0.13 0.07 0.06 72

Data modified from various sources.

tbl0003 Table 3 Habitats and global distribution of crustaceans utilized for human nutrition

Group Habitat Distribution (commercial fisheries)

Marine

Copepods Pelagic Norway, Canada, Japan

Cirripedes Rocky, coastal Portugal

Mysids Pelagic, coastal, estuarine Japan, South-east Asia, China, Korea

Euphausiids Pelagic, offshore Antarctica, Canada, Norway, Mediterranean

Sergestids Pelagic, coastal, estuarine China, South-east Asia, Japan, East Africa, India,

Brazil, Surinam, Philippines

Penaeid shrimp (60 species) Benthic, soft-substrate, nutrient-rich,

estuarine, coastal

Worldwide between 40

N and 40

S

Plesiopenaeus Benthic, soft-substrate, deep-water Atlantic, Australia, South Africa

Pleoticus Soft-substrate, deep-water South-west Atlantic

Caridean shrimp

Crangon Benthic, soft-substrate, coastal Europe, former Soviet Union, Algeria

Pandalus Benthic, coastal to 1500 m North Pacific, Atlantic

Palaemon Benthic, rocky, coastal Europe, Algeria

Stomatopoda Benthic, rocky, coastal Tropical to Mediterranean

Lobsters

Homarus Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal to 700 m North Atlantic, Mediterranean

Nephrops Benthic, soft substrate, 15–800 m North-west Atlantic, Mediterranean

Panulirids Benthic, rocky, coastal, 700 m 30

N–50

S worldwide

Syllaridae Benthic, soft-rocky, coastal Mediterranean, Japan, Indian Ocean

Anomurans

Galatheids Benthic, rocky, coastal Mediterranean, Japan, western USA

Lithodes Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal South-west Atlantic

Paralithodes Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal North-west Pacific

Crabs

Chionecetes Benthic, rocky, coastal North-west Atlantic, north-west Pacific,

east central Atlantic

Maia Benthic, rocky, seaweeds, coastal Mediterranean

Cancer Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal Africa, north-east and central Atlantic, Mediterranean,

north-east and -west Pacific, east central Pacific

Portunids Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal North-east Atlantic, Asia, west Pacific

Callinectes Benthic, rocky-soft, coastal, shelf edge West and north-west Atlantic

Scylla serratus Benthic, mangal, coastal Asia, India, west central Pacific

Geryon Benthic, soft, 300–1500 m North-west Atlantic

Fresh water

Caridean shrimp

Macrobrachium Estuaries, rivers, benthic, soft-substrate Tropical, introduced worldwide

Palaemonids Estuaries, rivers, lakes, soft, benthic Tropical

Astacidea

Crayfish Rivers, lakes, streams, rocky-soft, vegetated Temperate to tropical, worldwide

SHELLFISH/Characteristics of Crustacea 5209

0019 Sexes are separate in most crustaceans, but even

some advanced malacostracans such as Pandalus

may be protandrous hermaphrodites (maturing first

as males, then later changing sex). Gonads are

paired structures which are found in various regions

of the trunk and empty via genital pores, usually

on a trunk sternite. In male decapods an anterior

pair of pleopods is modified for sperm transfer.

Sperm is deposited directly into the oviduct or into

a seminal receptacle, where it may be stored for

some time. Crustaceans may brood fertilized eggs,

usually in an external pouch (mysids) or attached

to pleopods (most decapods), but exceptionally

(penaeids) may release their eggs freely into the

sea.

0020 Typically crustacean eggs hatch into planktonic

larval forms, although these are suppressed, for

example, in the Mysidacea, Amphipoda, Isopoda

and fresh-water Astacidea, where direct development

occurs. The most primitive larva is the nauplius, with

a single median simple eye and three pairs of bira-

mous limbs; this is followed by the zoea and mega-

lopa, gaining additional limbs and segments at each

molt. A wide variation in numbers of larval stages and

duration is seen; penaeids have 12 stages extending

over 13 days, homarid lobsters four stages over 15

days, whilst the planktonic life of palinurids may

extend up to 12 months.

0021 Table 2 gives the composition of crustaceans com-

monly consumed by humans and reveals that all

are low in saturated fats, high in polyunsaturates,

particularly the highly unsaturated n-3 series, and

contain medium levels of cholesterol. (See Carbohy-

drates: Requirements and Dietary Importance;

Energy: Measurement of Food Energy; Fats: Require-

ments; Protein: Requirements.)

0022 Several crustacean groups (copepods, branchiur-

ans, cirripedes, and isopods) have given rise to para-

sites which may cause serious infestations in edible

fish and shellfish.

Habitats and Distribution

0023 Apart from the pelagic zooplanktonic copepods,

mysids, euphausiids, and sergestids, which are mainly

fished commercially in colder productive waters

(Table 3), most other crustaceans only occur in com-

mercial densities in shallow coastal seas. The fast-

growing, high-value penaeid shrimp are restricted to

warmer waters, as many have life cycles associated

with estuarine mangals, and many burrow in sands

and muds. In contrast, the slower-growing caridean

shrimps are centered in the northern boreal region,

where the shallow-sea pandalids make up the bulk of

the fisheries.

0024The slow-growing homarid lobsters also have a

cold-to-warm temperate distribution and are re-

placed in warmer seas by the panulirid and scyllarid

lobsters. The most productive crab fisheries used to

be those for king crabs (Paralithodes) and snow crabs

(Chionecetes) from the North Pacific and Alaska, but

blue crabs (Callinectes) from the western Atlantic

have recently produced the highest landings. Al-

though most lobsters and crabs show a preference

for rocky habitats, both Cancer and Homarus will

construct burrows in soft substrates.

0025Many crustacean groups have invaded fresh-water

habitats, but only caridean shrimp, notably Macro-

brachium and crayfish, attain commercial fishery

sizes. The former are restricted to tropical waters,

whilst the latter occur worldwide. European crayfish

populations declined as a result of disease, but recent

introduction of expatriate species has led to these

becoming pests, particularly in Africa and southern

Europe.

See also: Carbohydrates: Requirements and Dietary

Importance; Energy: Measurement of Food Energy; Fats:

Requirements; Protein: Requirements

Further Reading

Bowman TE and Abele LG (1982) Classification of the

recent crustacea. In: Bliss DE (ed. in chief) The Biology

of Crustacea, vol. 1, pp. 1–25. New York: Academic

Press.

Brusca RC and Brusca GJ (1990) Invertebrates, pp. 1–922.

Sunderland, Massachusetts: Sinaver Associates.

Provenzano AJ (1985) Economic aspects: fisheries and cul-

ture. In: Bliss DE (ed. in chief) The Biology of Crustacea,

vol. 10, pp. 1–331. New York: Academic Press.

Commercially Important

Crustacea

B D Paterson, Bribie Island Aquaculture Research

Centre, Bribie Island, Australia

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Visit a fish market, supermarket, or restaurant any-

where in the world, and a variety of crustaceans are

likely to be presented for sale. The particular species

found will depend greatly upon the country and

the region concerned. However, as crustaceans and

other kinds of seafood move further afield with the

5210 SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea

increasing international trade in food products, this

means both an increasing variety in the product dis-

played in the major markets of Asia, USA, and

Europe, and more intense competition within broad

product categories. As a consequence, the names of

imported product can be a hot ‘branding’ issue

amongst local producers. But rather than perpetuat-

ing arbitrary distinctions, for example about what

constitutes a ‘true’ lobster, in order to objectively

come to grips with the varieties of crustaceans

produced in significant quantities throughout the

world, it is easier to consider the three broad product

groups; shrimp, lobsters, and crabs. These commod-

ity divisions nevertheless mirror broad taxonomic

differences, largely because the morphology of

crustaceans has a large impact on their processing

and marketability.

0002 Most of the commercially important crustaceans

are decapods, the group containing the largest and

most familiar crustaceans (Table 1). The sheer diver-

sity and global distribution of fished and cultured

crustacea seemingly count against any attempt at a

detailed statistical compilation. But it is possible,

within the limits of the data available, to find major

patterns in the production figures and identify out-

standing species. Of course, species that do not rate

highly in terms of global production can still be com-

mercially important. They may be high in value and

on display, such as crustaceans marketed alive, or

they may be less valuable but still contribute locally

to nutrition, employment, and prosperity. Commer-

cial exploitation itself is enough to warrant local

regulation and management of stocks or farming

operations, though, now, the viability of ‘local’

industries and the quality of their products have

reached new horizons of concern, now that quality

and sustainability are the concern of world consumers

and trade regulators.

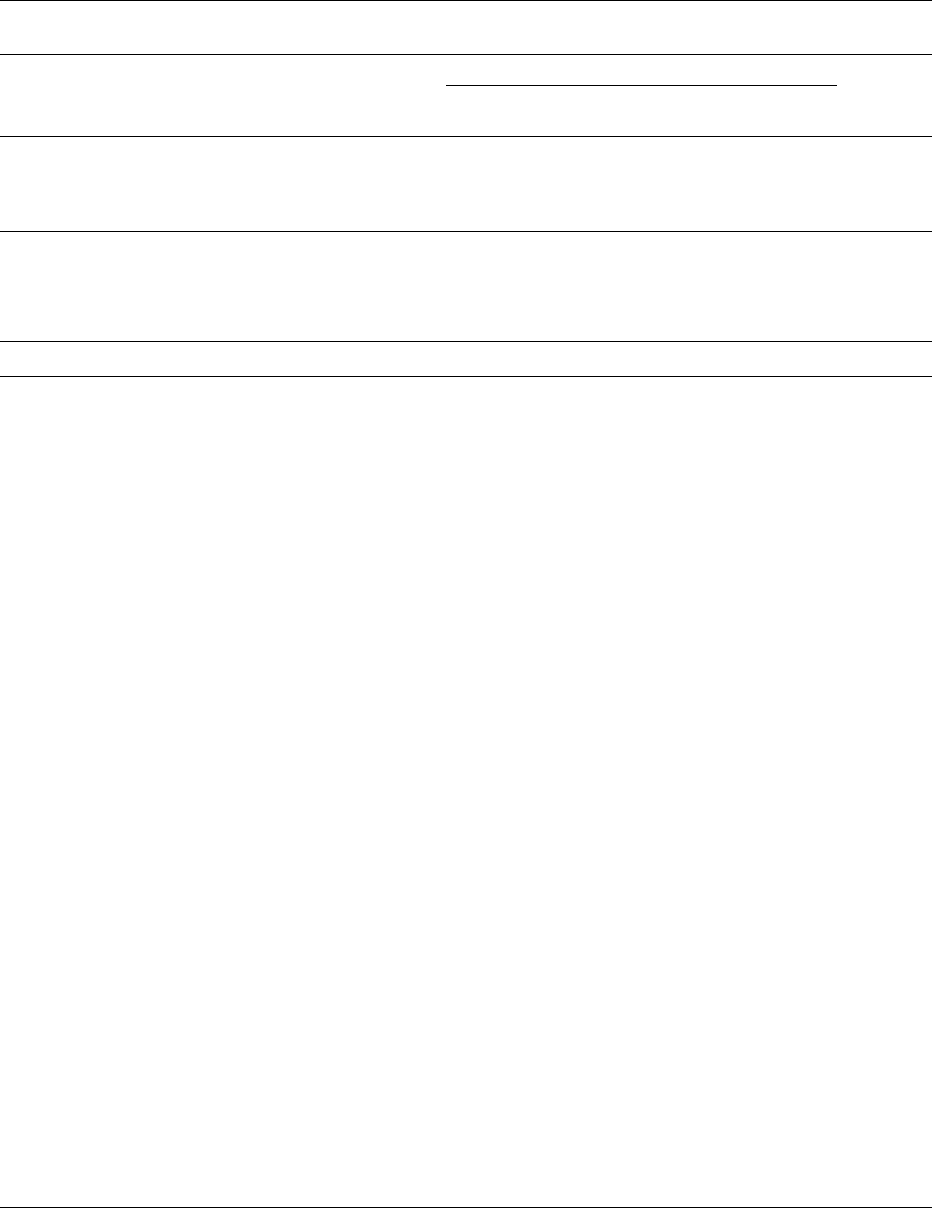

0003The total global production of crustaceans from

fisheries and aquaculture was 7.8 million tonnes in

1999, and crustaceans represented about 20.1% of

global aquaculture production in that year. Shrimps

and shrimp-like crustaceans account for about half

the global crustacean trade, largely due to the large

output of shrimp fisheries and an increasing compon-

ent of farmed tropical marine shrimp. About 81%

(6.3 million tonnes) of harvested crustaceans came

from capture fisheries, so the taxonomic/market

breakdown of this group (Figure 1) still has a signifi-

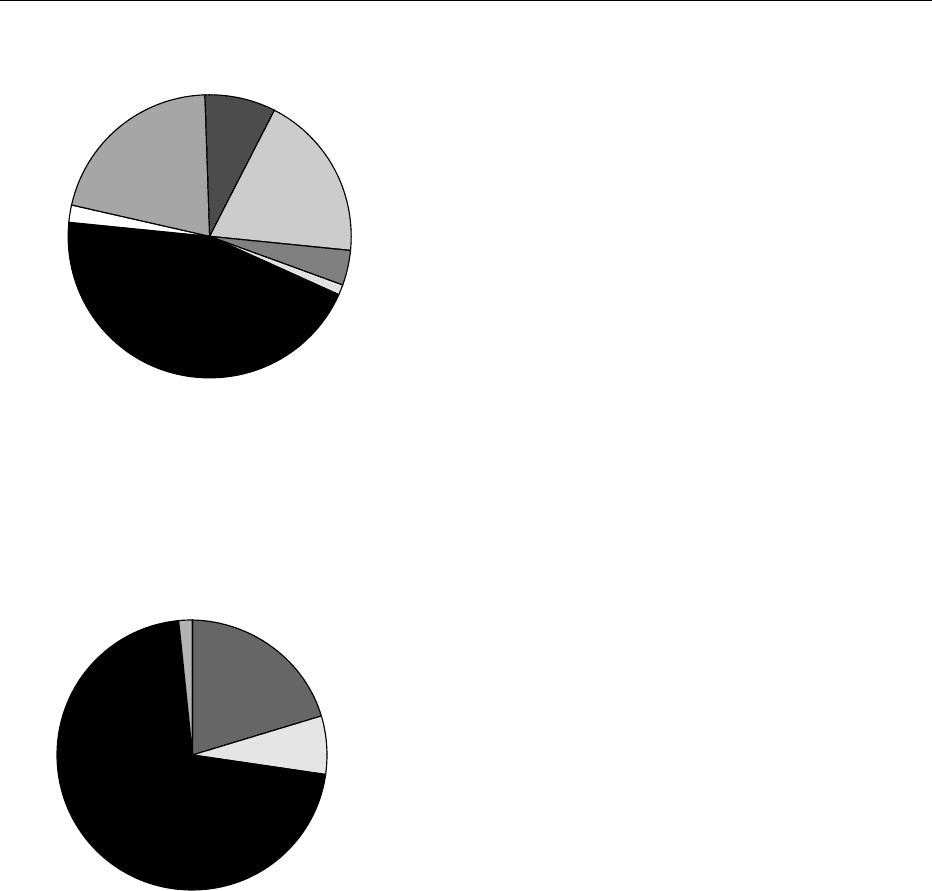

cant effect on global totals. Marine shrimp currently

dominate the crustacean farming sector (Figure 2),

with much of the remaining farm production based

in freshwater.

0004Beyond the level of the total contribution by vari-

ous taxa, it is not always possible to categorically

identify the most important species by isolating

these data from the production figures. Sometimes,

the compiled global statistics for particular groups

include large percentages of production that cannot

be assigned to anything but the broadest taxonomic

categories. Nevertheless, the species that emerge from

the data contain no surprises, even where relatively

large proportions of production remain unspecified.

0005While the better known crustaceans originate from

the world’s oceans, it would be wrong to discount

altogether the 10% of global production of crust-

aceans that originates from freshwater sources.

While these of course are also shrimp, crabs, or

indeed ‘lobsters’, they deserve separate treatment,

because they do not necessarily compete in the same

market segments as their marine relatives.

Marine Shrimp

0006The suborder Natantia (shrimps and prawns) are

decapod crustaceans adapted for swimming, with

a light cuticle and a well-developed abdomen with a

tbl0001 Table 1 Taxonomic relationships amongst commercially

important crustacea

Crustacea (Class)

Decapoda (Order)

Natantia (Suborder)

Caridea (Infraorder)

. Crangonidae (Family) Crangon crangon

. Palaemonidae (Family) Macrobrachium rosenbergii

. Pandalidae (Family), e.g., Pandalus borealis

Penaeoidea (Infraorder)

. Penaeidae (Family), e.g., Penaeus spp.

. Sergestidae (Family), paste shrimp, Acetes japonicus

Reptantia (Suborder)

Anomura (Infraorder)

. Galatheidae (Family), Squat lobsters, Pleuroncodes

monodon

. Lithodidae (Family), Stone crabs, Paralithodes

camtschaticus

Astacura (Infraorder)

. Cambaridae (Family), Freshwater crayfish, e.g.,

Procambarus clarkii

. Nephropidae (Family), Lobsters, e.g., Homarus

americanus, Nephrops norvegicus

. Parastacidae (Family) Freshwater crayfish, e.g.,

Cherax quadricarinatus

Brachyura (Infraorder)

. Cancridae (Family), Edible crabs, e.g., Cancer spp.

. Majidae (Family), Spider crabs, Chionoecetes spp.

. Portunidae (Family), Swimming crabs Portunus

trituberculatus, Callinectes sapidus

Palinura (Infraorder)

. Palinuridae (Family), Spiny lobsters, e.g., Panulirus

argus

Euphausiacea (Order)

. Euphausiidae (Family), Krill, Euphausia superba

SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea 5211

full complement of swimmerets. The abdomen is also

used for the powerful tail-flicks that the shrimp uses

to flee danger, so it is ironic that it is this very adapta-

tion that makes shrimps so commercially attractive.

0007 Production of shrimp in 1999 was about 4 million

tonnes. There is sufficient detail in the global statistics

to be sure of the general spread of taxonomic groups,

as only about 13% of recorded production is un-

assigned. The diversity in this group is such that a

number of major taxonomic groups of shrimp and

shrimp-like organisms are involved. Three quarters of

the total shrimp production is represented by shrimps

of the Infraorder Penaeoidea, most of that accounted

for by several species of the diverse and widespread

Family Penaeidae (2.4 million tonnes). The Sergesti-

dae, a group common in deeper water, make up a

major slice of the remaining penaeoids harvested,

and most of that is the akiami paste shrimp Acetes

japonicus, a species used for manufacture of paste,

salted, and fermented products. While another major

superfamily, the Caridea accounts for only 10% of

the global production of shrimp (or 430 000 tonnes),

the bulk of that (91%) is represented by a single

North Atlantic species of pandalid shrimp, the North-

ern shrimp, Pandalus borealis. The remaining data

for the caridean shrimp are mostly taken up by land-

ings of common shrimp Crangon crangon (around

37 000 tonnes).

0008The diversity of the shrimp group is such that it is

not possible to discuss all in detail. If we arbitrarily

consider species to which landings represent individu-

ally more than 10% of total shrimp landings, four

species stand out. The paste shrimp and the Northern

shrimp (Acetes japonicus and Pandalus borealis) have

already been mentioned, but to this group should be

added the giant tiger shrimp, Penaeus monodon (on

the basis of farmed production!), and the southern

rough shrimp, Trachypenaeus curvirostris. But this

summary perhaps unfairly overlooks the diversity of

other species of the Penaeidae such as the banana

shrimp Farfantepenaeus merguiensis, P. chinensis,

and P. aztecus.

0009By 1999, aquaculture accounted for over a third of

of global shrimp production (1.1 million tonnes). As a

market segment, farmed shrimp has been floating

around 20–25% of global shrimp landings since

the mid-1990s, the upward trend being checked or

reversed by outbreaks of shrimp viral diseases at

various times around the world, with consequences

for supply and pricing felt throughout the market.

The farmed shrimp are also penaeids and about

half of the total is represented by farmed production

of giant tiger shrimp Penaeus monodon. The three

most notable farmed shrimp in the FAO statistics

(in order of decreasing quantities) are the giant

tiger shrimp (Penaeus mondon), the Pacific white

shrimp Litopenaeus vannamei, and the Chinese

white shrimp Penaeus chinensis. L. vannamei is

farmed in the Americas, while the other two species

are produced in South-east Asia. These species also

figure highly in wild production statistics, though the

farmed production for these species now exceeds

the corresponding fisheries production.

0010Shrimp, which probably owes its dominance to

sheer biological abundance as well as simple peeling

and high meat recovery (50–60% of fresh weight),

lends itself to a diversity of processed fresh/frozen and

1%

45%

2%

21%

8%

19%

4%

Freshwater

crustaceans

(various)

Marine crabs

(Brachyura)

Marine

lobsters

Marine

crab-like

lobsters

(Anomura)

Marine shrimp

(Natantia)

Krill

Unspecified

fig0001 Figure 1 Global fisheries production of major product/taxo-

nomic groups of crustaceans in 1999. From Anon (1999) FA O

Fishery Statistics: Capture Production; Aquaculture Production; Com-

modities, vol. 88(1–3). Rome: FAO.

71%

2%

20%

7%

0%

Unspecified

Freshwater

crustaceans

(various)

Marine crabs

(Brachyura)

Marine

lobsters

Marine shrimp

(Natantia)

fig0002 Figure 2 Global farmed production of major product/taxonomic

groups of crustaceans in 1999. From Anon (1999) FA O Fi s h e r y

Statistics: Capture Production; Aquaculture Production; Commodities,

vol. 88(1–3). Rome: FAO.

5212 SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea

packaged, value-added forms. Live marketing of the

kuruma shrimp (Marsupenaeus japonicus) involves

relatively small quantities but is noteworthy for the

high prices achieved. Chilled, raw shrimp have a

limited shelf-life, so much of the product is processed

at sea or on farm in various ways to allow for

marketing. This might involve simply packaging and

freezing the raw or cooked shrimp in a manner suit-

able for sea-freight, but more sophisticated process-

ing is increasingly being practiced (Figure 3).

0011 One concern with minimal processing is ‘black

spot’, a form of enzymatic spoilage common to

commercial crustacea. This melanosis is mediated

by polyphenoloxidases in the shell or hemolymph

(blood). (See Browning: Enzymatic – Biochemical

Aspects.) ‘Black spot’ can be avoided to some extent

by removing the shell or by thorough cooking (to

deactivate the enzymes), or treating the product to

inhibit the formation of melanin. A widespread

‘black-spot’ treatment is to dip the raw or cooked

shrimp in a solution of sodium metabisulfite or re-

lated chemicals (which scavenge oxygen, a require-

ment for melanosis). However, concerns over

introducing undesirable sulfite residues into the prod-

uct has recently led to adoption of other methods.

One of these involves an enzyme inhibitor (4-hexyl-

resorcinol), which interrupts the enzyme cascade

leading to melanin.

0012 Given the diversity of species, it would be wrong to

say that there is one homogeneous global market for

these ‘commodity’ shrimp, though few sectors seem

immune from the ups and downs of supply and

demand. The meat of different species varies in ap-

pearance, flavor, and texture, and this still explains

some market segmentation in countries or regions

where historically consumers ate particular types or

shrimp or prawns. Marine penaeid shrimp have al-

ready made inroads into the European market, where

Pandalus borealis once held sway, but even these

penaeids vary. Consider the contrast, in terms of

both raw and cooked meat between the highly pig-

mented giant tiger shrimp and various species of

‘white’ shrimp marketed.

0013However, ultimately, national tastes may come

to mean little when products are highly processed,

breaded, and packaged. Raw shrimp can be headed

and the tail split (or ‘butterflied’), breaded, and stored

frozen in a form ready for cooking. Similarly, raw or

cooked shrimp can be shelled and the peeled meat

frozen and once again marketed as a convenience

product. The processing, freezing, and cooking equip-

ment used varies, with the cost of labor in the country

concerned having a major role. The packaging used

can range from bulk packs to prepackaged individual

serves.

0014The shrimp sector has not been without troubles.

Sporadic disease episodes in the farming sector have

impacted upon supply and in recent years have raised

concerns about the transfer of shrimp diseases by the

global trade in shrimp. In addition, major seafood

importing markets such as the USA, the European

Union (EU), and Japan have emphasized the quality

and safety of food imports by insisting on the

adoption of Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point

(HACCP) and related schemes. The trade in ‘com-

modity’ shrimp has had to fall in line with this, since

imports from noncompliant countries have been

banned. Various segments of the shrimp industry

have also found themselves squarely in the sights

of environmental activists concerned with reducing

trawl by-catch and stemming the impact of the

farming sector. For example, the fate of turtles

drowned in trawls prompted calls in the USA for

shrimp imports to be banned from countries using

gear considered harmful to turtles. This has seen an

increased emphasis on ‘turtle excluders’ and other

kinds of by-catch reduction devices amongst world

shrimp capture fisheries. The environmental impact

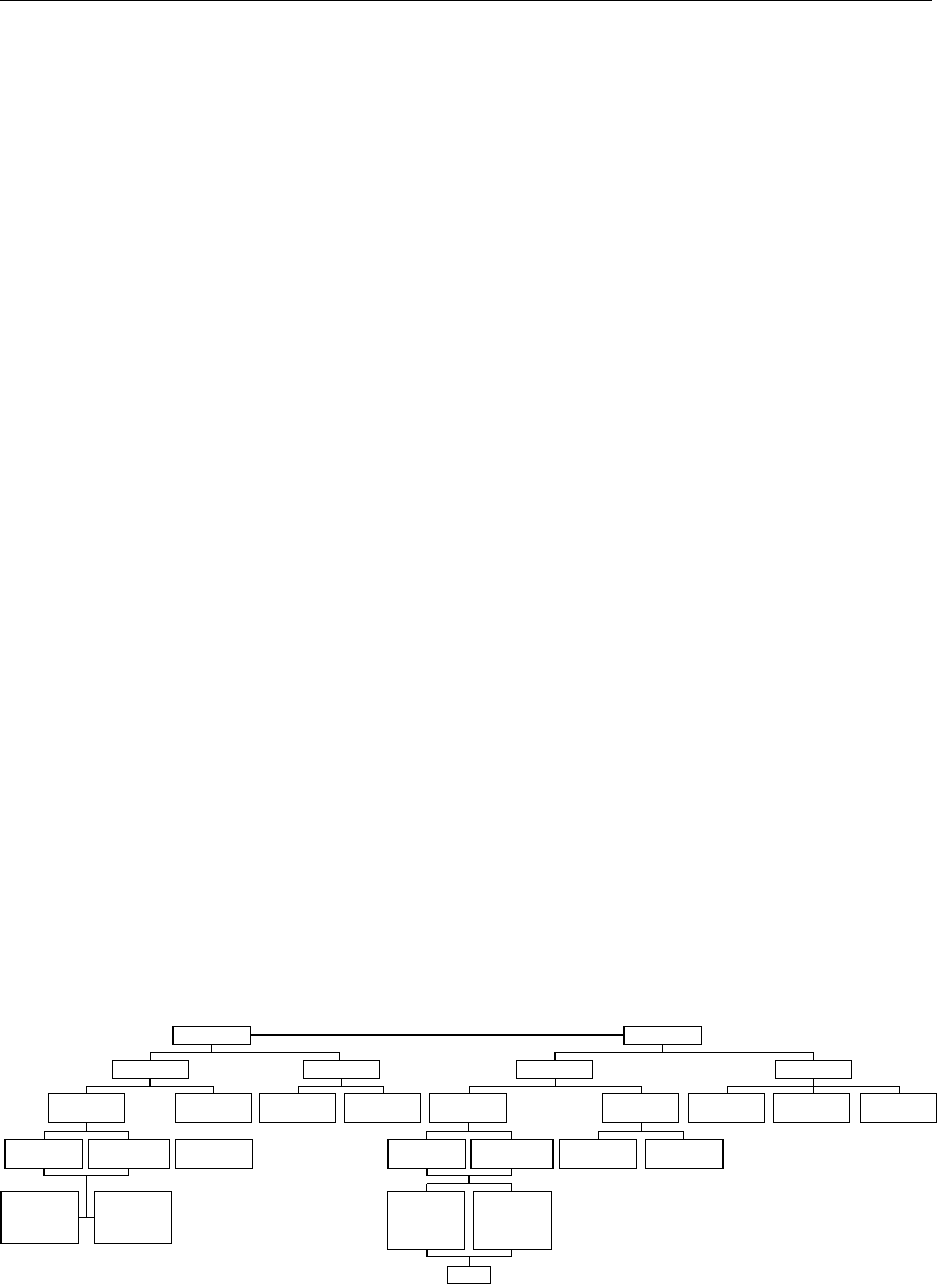

Cooked

Headed

Shell on tailPeeled tail

De-veined Not de-veined Frozen

Frozen

Frozen

Raw

Headed

Shell on tail Dried

Frozen

Frozen

Whole Whole

Chilled

Chilled

Chilled

Not breaded

Not de-veined

Peeled tail

or tail fan on

De-veined/

Butterflied

Convenience

products

e.g. breaded

skewered

Frozen

Canned/

bottled

fig0003 Figure 3 Summary of processing and storage methods applied to raw and cooked shrimp. Based on Lee DO and Wickins JF (1992)

Crustacean Farming. Oxford: Blackwell Scientific.

SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea 5213

of shrimp aquaculture is another area of controversy.

All agriculture has some environmental impact, and it

would be surprising if any global industry producing

around a million tonnes of product annually had no

local impact on the environment. Nevertheless, the

recurrent problems with disease outbreaks certainly

point to areas where farm management has needed

to become more sustainable. Producers now appre-

ciate the power that can be wielded by consumer

campaigns, and development of more environmen-

tally friendly farming methods is already a major

priority.

Marine Crabs

0015 The so-called ‘true’ crabs and, to some extent, certain

‘crab-like’ lobsters are the pinnacle of the tendency

amongst decapod crustaceans to abandon the pelagic,

swimming lifestyle. Their commercial importance no

longer relies on tail meat, owing to their rudimentary,

indeed vestigial, abdomen. Crabs hide from attack in

burrows, buried in sand or beneath rocks, or perhaps

rely for protection upon sheer size, a heavy cuticle,

and threatening, sometimes well-muscled claws.

0016 The marine production of true crabs in 1999 was

about 1.3 million tonnes, or about 16.4% of global

crustacean production. It is hard to be definitive as to

the contribution of individual species to this total. As

much as 26% of the total is represented by statistics

that are only assigned to the broadest categories. Still,

the available detail reveals a number of significant

fisheries for swimming crabs of the Family Portuni-

dae, particular centered in Asia. This group of crabs

swim using a pair of modified, paddle-like legs. This,

if anything, reiterates the capacity of evolution to

reinvent a trait since lost in other crabs. About a

third of estimated true crab production is represented

by the swimming crabs Portunus trituberculatus

(22%) and P. pelagicus (10%). Another important

swimming portunid, the blue crab Callinectes sapidus

from the east coast of the USA represents just 8% of

the crab total. To contrast this approximately 40%

share for portunids, the spider crabs (queen, snow, or

tanner crabs, Chionoecetes spp.) together account for

16% of the total for true crabs. A diversity of other

species of crab are harvested, and perhaps a discus-

sion of the true crabs should not omit mention of the

edible crabs, Cancridae, represented by various

species of Cancer.

0017 A small number of crab-like lobsters are not

included in this total for true crabs. Marine crab-

like lobsters such as stone crabs (Lithodidae, 57 500

tonnes) and squat lobsters (Galatheidae, around

26 500 tonnes) together account for only about 1%

of global crustacean production. Taxonomically, these

crustaceans belong to the diverse Infraorder Anom-

ura. This assemblage of crustaceans has a diversity of

body forms, though again with a trend for the abdo-

men to shrink. The major species of stone crabs and

squat lobsters are, respectively, the Alaskan king crab

Paralithodes camtschaticus and the red squat lobster

Pleuroncodes monodon.

0018Crabs are harvested in a variety of ways, ranging

from trawls to pots. Some farm production of portu-

nid crabs has been achieved using Scylla spp. and

Portunus pelagicus in South-east Asia, but it has

some way to go before it reaches levels of production

typical of shrimp farming. Probably the most unusual

method of harvesting a crab or indeed any crustacean

is one that takes advantage of the ability of crust-

aceans to regrow missing limbs. In the fishery for

the stone crab Menippe mercenaria, only the claws

are harvested, and the crab is returned to the sea, to

grow new claws! The processing and marketing of

newly molted blue crabs C. sapidus as ‘soft-shell’

crabs is another case where crustacean physiology is

exploited commercially.

0019Processing options for crabs are broadly similar to

those applied to shrimp, though in contrast to shrimp,

many ‘minor’ species of crabs are often sold, trans-

ported, and marketed while alive, giving them a high

level of consumer recognition. The live trade is

preferred over that for raw chilled or frozen product,

because the digestive gland (hepatopancreas) breaks

down soon after death, discoloring the meat and

releasing digestive proteases that readily soften the

meat.

0020Unlike shrimp and lobsters, crabs cannot be con-

veniently ‘headed’ to remove the digestive gland.

Instead of ‘peeling’ cooked crabs, more ingenuity is

required to cut or saw through the thicker exo-

skeleton. The catch from the big tonnage fisheries is

processed in large quantities and may reach the con-

sumer in a highly refined form. Crabs taken live to a

processor can be cooked (to inactivate the enzymes)

and sold either whole/frozen or in a progressively

broken apart form, to give packaged/frozen or canned

meat. Processing the cooked product involves break-

ing open the shell and extracting the meat associated

with the leg muscles and the claws. Though the details

differ between species, picked meat production is

probably as close as the crab sector comes to achiev-

ing the ‘commodity’ status as a source of convenience

food. Conditions of strict hygiene must be employed

during picking, because physically breaking the shell

to extract meat presents an opportunity for the intro-

duction of microbial contamination (e.g. Listeria

and other pathogens), unless the product is further

pasteurized. These risks can be addressed using the

principles of HACCP.

5214 SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea

0021 Significant quantities of crabs are processed by

individual factories, which translates into a consider-

able amount of waste. As companies in some coun-

tries are increasingly finding that waste costs money

to dispose of, attention continues to be paid to eco-

nomically recovering saleable material or products

(e.g., chitin, astaxanthin, and other biological mater-

ial) from the waste.

Marine Lobsters

0022 While armored and strictly designed for walking,

marine lobsters (and crayfish and indeed some

‘shrimp’ from freshwater) retain the basic body plan

of pelagic crustaceans. The cephalothorax or head of

lobsters is more prominent than is generally the case

for shrimp, but the abdomen or ‘tail’ is only slightly

diminished and, when danger threatens, can still

generate powerful tail-flicks.

0023 Marine lobsters account for only about 3% of total

global landings, or nearly 229 000 tonnes. At least

three-quarters of this is in the form of clawed

Homarid and Nephropid lobsters from the North

Atlantic (from the Infraorder Astacura). The Ameri-

can lobster Homarus americanus, from the USA and

Canada, accounts for almost 40% of the lobster land-

ings, followed by the Norway lobster Nephrops nor-

vegicus at about 27%. Lesser quantities of European

lobster Homarus gammarus, and a few species of

other minor Nephropids (e.g., Metanephrops spp.)

are caught elsewhere. The other major group of lob-

sters, the Infraorder Panulira – the spiny and rock

lobsters – has a more widespread distribution. These

lobsters lack claws as such, and instead have promin-

ent spiny antennae. The Caribbean spiny lobster

Panuilrus argus accounts for 16% of global lobster

landings, but there are several other Panulirus, Pali-

nurus, and Jasus species harvested commercially

throughout the tropical to temperate seas of the

world.

0024 Harvesting methods for lobsters vary from species

to species, but potting and trawling are practiced.

Clawed lobsters can be produced in hatcheries, but

currently, this is for reseeding programs rather than

aquaculture per se. The numerous long-lived plank-

tonic larval stages of typical panulirids is a major

practical obstacle to the aquaculture of panulirids,

with aquaculture ventures mostly concentrating on

the collection of wild seed. Commercial production

of farmed shovel-nosed lobsters Thenus orientalis

from the hatchery is currently under development,

while research continues on aquaculture of other

panulirids. Like crabs, lobsters tend to be marketed

whole and alive, though frozen product is also dis-

tributed cooked whole or tailed. Again, the major

objective is to deal with quality loss associated with

breakdown of the hepatopancreas. There is also some

cutting, chopping, and meat picking from cooked

lobsters, to produce both canned and frozen product.

Where live transport of lobsters is logistically difficult

(e.g., Pacific Islands), there is a preference for

marketing frozen raw tails rather than freezing

whole animals with the hepatopancreas intact.

Others

0025Global production of crustaceans from freshwater is

estimated at about 817 000 tonnes (about 10% of the

total). About half of that is fisheries data from Asia

and particularly China, and is not identified to species

level. To the extent that the data allow, two cultured

species, the Chinese river crab Eriocheir sinensis and

the giant river prawn Macrobrachium rosenbergii,

together account for at least 33% of the global pro-

duction of freshwater crustaceans. Another recog-

nized aquaculture species in the USA, Procambarus

clarkii, accounts for only 2% of the total landings,

and beyond this, the landings are divided amongst

numerous species that may of course be relevant in a

geographical context. Freshwater crustaceans include

numerous freshwater crayfish of the Astacidae,

Cambaridae in Europe and the Americas, and a

small representation from the Parastacidae (ori-

ginally from Australia).

0026Product from freshwater tends to have a milder

flavor, largely due to the different demands for os-

motic regulation faced by freshwater-adapted crust-

aceans. Anatomically, commercial freshwater shrimp

and crayfish also tend to have relatively smaller ab-

domens leading to less favorable meat recoveries than

from their marine counterparts, though the variety of

raw, cooked, and processed products can come close

to rivalling that of marine shrimp in variety, if not

in quantity. Translocation and release of Cambarid

species into Europe have seen the spread of an intro-

duced crayfish disease that has decimated native cray-

fish populations in some areas. Freshwater shrimp or

prawns such as M. rosenbergii belong to the Caridea

(Palaemonidae).

0027Another notable group, the krill are small shrimp-

like crustaceans that swarm in the plankton of the

world’s oceans and form an importance food source

for marine foods chains (and particularly many

whales). These small shrimp are a different order of

Crustacea altogether, the Order Euphausiacea. Global

landings have varied between 80 000 and 100 000

tonnes for the past few years. One important use of

dried krill meal is for aquaculture feed ingredients

(see Fish Meal). Excitement about using krill as a

human food source has been tempered in recent

SHELLFISH/Commercially Important Crustacea 5215

years by a more realistic understanding of the re-

source and its limitations.

0028 If imitation is considered to be the most sincerest

form of flattery, then the very existence of surimi is

further evidence of the commercial importance of

crustaceans. Surimi is the deboned, washed, and

gelled protein manufactured from white fleshed fish.

Formed into sticks, flakes and chunks, the edges are

coloured red to resemble picked crab meat.

See also: Browning: Enzymatic – Biochemical Aspects;

Fish Meal; Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point

Further Reading

Anon (1999) FAO Fishery Statistics: Capture Production;

Aquaculture Production; Commodities, vol. 88(1–3).

Rome: FAO.

Ingle R (1997) Crayfishes, Lobsters and Crabs of Europe.

London: Chapman & Hall.

Lee DO and Wickins JF (1992) Crustacean Farming.

Oxford: Blackwell Scientific.

Ruiter A (ed.) (1995) Fish and Fishery Products: Compos-

ition, Nutritive Properties and Stability. Wallingford,

UK: CAB International.

Characteristics of Molluscs

K J Boss, The Agassiz Museum Harvard University,

Cambridge, MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Molluscs constitute a unique phylum of animals, the

Mollusca, which are characterized by a combination

of morphological and anatomical features separating

them from all other invertebrate organisms. Many

common names, such as snails, clams, and squids,

apply to representatives of these animals, which

number fewer than 50 000 living species. Molluscs

are known to have diversified early in the fossil

record, namely the Cambrian of the Paleozoic over

half a billion years ago; the antecedent or ancestral

mollusc is presumed to have evolved in the Precam-

brian and many different lineages have radiated into

the vast array of ecological niches of the world’s

biotopes.

0002 Molluscs are widespread in marine environments,

living from the shore to the greatest abyssal depths

and occurring in pelagic or oceanic realms as well as

benthically, both on and in all kinds of substrates.

In some parts of the world, they dominate the

intertidal zone, and in the recently discovered aphotic

deep-water vents and seeps as well as other oxygen-

depleted environments, molluscs, especially mussels

and certain clams, are particularly conspicuous, fre-

quently utilizing endosymbiotic chemoautotrophic

bacteria. Groups of representative snails and bivalves

have also successfully adapted to terrestrial and fresh-

water habitats. Finally, some species have become

specialized endoparasites.

0003In adult size, molluscs range from tiny gastropods

and bivalves less than 1 mm in diameter or length to

the giant squid which may be over 15 m long and

upwards of 1000 kg in weight.

Typical Morphological and Anatomical

Features

0004Molluscs are protostomous coelomates, exhibiting

spiral, determinate cleavage and schizocoely as well

as having trochophore larvae and the blastopore

forming the mouth of the adult. They usually possess

all or a combination of the following features: (1) a

reduced coelom and vestiges of metamerism; (2) a

mantle or fleshy epidermis of the dorsal body wall

which has glands capable of secreting calcium car-

bonate to form an exoskeletal shell or shelly parts,

such as plates, spines, and spicules; (3) a mantle cavity

or an invagination of the mantle which contains a

pair or more of specialized respiratory structures,

the ctenidia or gills, and into which the digestive,

metanephridial excretory, and reproductive systems

debouch their products; (4) the ventral body surface

modified into a pedal groove or muscularized foot for

progression or locomotion; (5) a special chitinized,

rasp-like tongue or radula; (6) an open hemocelic

circulatory system with a chambered heart having

auricles and ventricles. Additionally, the nervous

system has variously paired ganglionic portions, par-

ticularly cerebral, pedal, and visceral ones, as well as

ventral anteroposterior cord-like connective elem-

ents; specialized sensory structures were evolved for

olfaction, vision, balance, and tactile stimulation.

0005Primitively, these animals were gonochoristic, that

is, having the male and female sexes in separate

individuals; fertilization was external and the eggs

developed into pelagic larvae; hermaphroditism with

both sexes in the same individual, brooding of eggs,

and ovoviviparity are a few among many of the

modifications in the reproductive strategies of these

animals.

Taxonomy of the Group

0006Currently seven classes of living molluscs are recog-

nized. The entirely marine, shell-less Aplacophora,

5216 SHELLFISH/Characteristics of Molluscs