Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

depending on variety and environment. The more

a-acids, the greater the bitterness potential.

0027 There are three different a-acids in hops, differing

in side-chain structure. The a-acids are isomerized to

form the more soluble and bitter iso-a-acids during

wort boiling (Figure 2). Each iso-a-acid has two

isomers, cis and trans, with differing orientation of

the side chains. The six iso-a-acids have a range

of bitterness intensities and it is generally held that

the hops should have a relatively low level of cohu-

mulone.

0028 Apart from their impact on bitterness and foam,

the iso-a-acids have strong antimicrobial properties

and inhibit many Gram-positive bacteria.

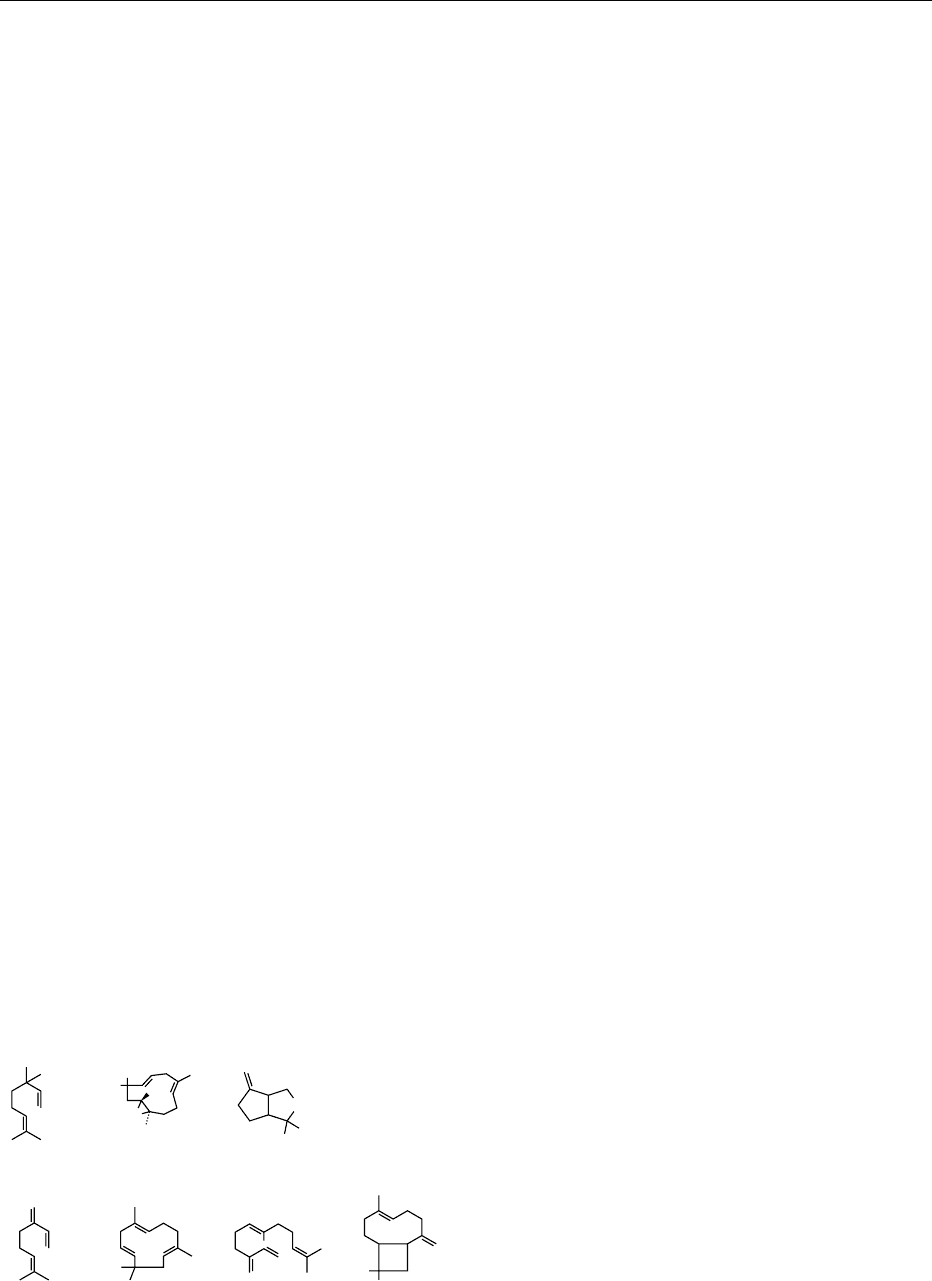

0029 Hops comprise 0.03–3% w/w essential oil,

comprising a complex mixture of more than 300

compounds (Figure 3). The components are very

volatile and tend to be lost during wort boiling. To

ensure hoppiness in beer it is necessary to add a

proportion of the hops late in the boil (late hopping,

associated with lager-style products) or to the finished

beer (dry hopping, associated with some ales).

0030 Hops are either used in a traditional way as whole

cones, though increasingly after hammer milling and

extrusion into pellets, in which form they are more

stable and more efficiently utilized, or after extraction

by liquid carbon dioxide and isomerization by weak

alkalis. The latter products can be added to beer

downstream, greatly increasing the efficiency of

bitterness utilization and flexibility of product formu-

lation. The oils in such extracts may be separated

from the resins and also added to beer to provide

hoppy aroma.

0031 In some preparations the iso-a-acids are reduced,

using hydrogen gas in the presence of a palladium

catalyst. Such reduction prevents the formation of

the skunk-flavored 3-methyl-2-butene-1-thiol from

the side chains when the bitter compounds are ex-

posed to light. The reduced preparations can be used

in the production of beers for packaging into green

and clear glass bottles, which are particularly prone

to light damage.

Phenolic Materials

0032The simplest phenolic acid in beer is ferulic acid, a

molecule found associated with the arabinoxylan

component of the starchy endosperm cell walls. It

may have antioxidant properties both for the beer

and for the drinker’s body. When decarboxylated,

by an enzyme present in the yeast strains used to

make wheat-based beers though not barley-based

ones, 4-vinylguaiacol is produced, which has a dis-

tinct clove-like character.

0033Certain flavanoids, including catechin and querce-

tin, derive from the outer layers of malt and from

hops. They, too, may have antioxidant properties,

but when oxidized they polymerize, to produce tan-

noids that cross-link through the proline groups in

certain beer polypeptides to form the insoluble com-

plexes responsible for haze. Haze formation is

lessened by reducing oxygen ingress and by reducing

the levels of haze-forming polypeptides and pheno-

lics. Silica hydrogels, tannic acid, and the proteinase

papain have been used to attend to the former, while

polyphenols can be removed using polyvinylpolypyr-

ollidone (PVPP). Vigorous wort boiling and chilling

of beer to as low a temperature as possible without

freezing (1

C) are both important stages in the

colloidal stabilization of beer.

0034The level of tannic materials in beer is probably too

low to have any significant impact on astringency.

(See Tannins and Polyphenols.)

Other Flavor Components of Beer

0035The four main flavor features detected by the tongue

are bitterness, sweetness, sourness, and saltiness. The

nose detects the other characteristic aromas of beer

and this is a balance between positive and negative

notes, each of which may be due to more than a single

compound from different chemical classes. Although

some of these substances originate in the malt and

hops, many are products of yeast metabolism.

0036Esters Esters afford a fruity character to beer: two

of the most important components are ethyl acetate

and iso-amyl acetate. Esters are formed from their

equivalent alcohols when the acetate group is

available by not being needed for the synthesis of

key components (lipids) of the yeast membranes.

Therefore, factors that promote cell production

lower ester production, and vice versa. Ester levels

in beer are impacted, inter alia, by the ratio of

carbon to nitrogen in the wort and by the amount of

oxygen available to the yeast. The yeast strain is very

OH

O

H

O

Linalool

Myrcene Humulene Farnesene Caryophyllene

Hop ether

Humulene

epoxide

fig0003 Figure 3 Some components of the essential oil fraction in hops.

BEERS/Chemistry of Brewing 445

important; some strains inherently produce much

higher ester levels.

0037 Alcohols The alcohols are the immediate precursors

of the esters. As the esters are substantially more

flavor-active, it is important to regulate the levels of

the higher alcohols if ester levels are also to be con-

trolled.

0038 The higher alcohols (i.e., those larger than ethanol)

are produced by transformation of amino acids, so the

levels of amino acids in wort have a major impact:

the more amino acids available to the yeast, the

greater the production of higher alcohols. However,

Saccharomyces will also produce higher alcohols as

an offshoot of the metabolic pathways responsible for

amino acid elaboration, pathways that are particu-

larly significant when the amount of assailable nitro-

gen in the wort is low. Hence higher alcohol

production is increased when both too much and

too little amino nitrogen is available to the yeast.

Ale strains produce more higher alcohols than do

lager strains. Conditions favoring increased yeast

growth (e.g., excessive availability of oxygen) pro-

mote higher alcohol formation.

0039 Sourness This is due to the organic acids, such as

acetic, lactic, and succinic, produced by yeast during

fermentation. It is the H

þ

ion produced by their dis-

sociation that causes sourness. Higher levels of the

acids are produced in vigorous fermentations.

0040 Vicinal diketones The vicinal diketones (VDKs),

diacetyl and pentanedione, afford highly undesirable

butterscotch and honey characters respectively to

beer. These substances are offshoots of the pathways

by which yeast produces certain amino acids. Precur-

sors leak from the yeast and decompose spontan-

eously to form VDKs. Yeast, however, can

reassimilate the VDK, provided the cells are healthy

and remain in contact with the beer. Brewers may

allow a temperature rise of 2–3

C at the end of

fermentation to speed up the removal of VDK. Add-

itionally, a proportion of freshly fermenting wort is

introduced to the beer as an inoculum of healthy yeast

(a practice called krausening). Alternatively a bacter-

ial enzyme (acetolactate decarboxylase) can be added

to a fermentation; this enzyme converts acetolactate

to acetoin, thereby avoiding the much more flavor-

active diacetyl.

0041 Persistently high VDK levels may be a symptom of

infection by Pediococcus or Lactobacillus bacteria.

0042 Sulfur compounds In the right levels and propor-

tions, the sulfur compounds play a substantial role

in determining the character of diverse beers. Some

ales display a distinct hydrogen sulfide character

when first dispensed, albeit one which subsides to

reveal the dry hop character. Lagers often have a

more complex sulfury character, which for many

includes dimethyl sulfide (DMS), with its cooked

corn/parsnip note. DMS is the best understood of all

the sulfur compounds in terms of its production

route.

0043All of the DMS ultimately originates from a pre-

cursor, S-methylmethionine (SMM), which develops

in the barley embryo during germination. SMM is

heatlabile, breaking down rapidly at temperatures

above about 80

C in malting and brewing. Accord-

ingly, SMM is at a lower level in the more highly

kilned ale malts and, therefore, there tends to be less

DMS in ales. SMM is extracted into wort during

mashing and is broken down during boiling and in

the whirlpool. In a vigorous boil most of the SMM is

converted to DMS and lost by volatilization. In the

whirlpool the temperature is still hot enough to

degrade SMM, but conditions are nonturbulent and

the DMS tends to linger. Brewers aiming for a finite

level of DMS in their beer specify a target level of

SMM in the malt and will adjust the boil and whirl-

pool stages so as to deliver a certain level of DMS in

the pitching wort. In fermentation a great deal of

DMS is swept away with the CO

2

, hence the level

of DMS targeted in the wort is higher than that speci-

fied for the beer. Some of the DMS produced during

malt kilning is oxidized to dimethyl sulfoxide

(DMSO). This is not volatile but is water-soluble

and enters wort, to be reduced by yeast to DMS.

Hence the level of DMS in the finished beer is a

function of how much DMS is present in pitching

wort, how much is volatilized, and how much is

replenished via the reduction of DMSO.

0044There is no simple relationship between the level of

DMS in beer and the perception of its flavor. This is

because phenylethanol and phenylethylacetate inter-

fere with the perception of DMS. There must be many

other antagonisms of this type contributing to the

complexity of beer flavor, but they have not been

studied.

0045Hydrogen sulfide (H

2

S) is produced by yeast via the

breakdown of cysteine or glutathione, or by the re-

duction of sulfate and sulfite. A vigorous fermenta-

tion purges H

2

S and factors that hinder fermentation

(such as a lack of zinc or vitamins) will increase H

2

S

levels in beer.

0046Malty notes As well as being the source of the DMS

character in beer, malt contributes in other ways

to flavor. Malty character is in part due to isovaler-

aldehyde, produced by the reaction of leucine with

reductones in the malt. The toffee and caramel

446 BEERS/Chemistry of Brewing

character from crystal malts and the roasted, coffee-

like notes in darker malts are due to complex

components derived from amino acids and sugars

when they cross-react during kilning. Of equal im-

portance during kilning is the disappearance of grassy

and beany notes, due inter alia to cis-3-hexen-1-ol,

trans-2-hexenal, trans-2-cis-6-nonadienal, and 1-

hexanol.

0047 The cross-linking of sugars and amino acids in-

duced by heating in kilning and wort boiling leads

to the formation of melanoidins via the Maillard

reaction. The melanoidins are responsible for

imparting color to beer: darker beers are produced

from grists incorporating malts and other adjuncts

that have been kilned to more intense regimes. Poly-

phenol oxidation, occurring during wort production,

can make a significant contribution to color in some

of the paler beers.

0048Miscellaneous Acetaldehyde, which is converted to

ethanol in actively fermenting yeast, imparts an un-

desirable ‘green apples’ character to beer. High

levels of acetaldehyde are due to premature separ-

ation of yeast before fermentation is complete,

poor yeast quality, or infection by the bacterium

Zymomonas.

0049The short-chain fatty acids, with their rancid notes,

are offshoots in the synthesis of membrane lipids by

yeast. When yeast needs fewer lipids (when it needs to

grow less), these compounds accumulate.

0050Table 2 offers a summary of the approximate

chemical composition of a pilsner-type beer.

See also: Alcohol: Metabolism, Beneficial Effects, and

Toxicology; Antioxidants: Natural Antioxidants; Barrels:

Beer Making; Barley; Beers: Raw Materials; Wort

Production; Biochemistry of Fermentation;

Microbreweries; Carbohydrates: Classification and

Properties; Malt: Malt Types and Products; Chemistry of

Malting; Packaging: Packaging of Liquids; Phenolic

Compounds; Protein: Chemistry; Starch: Structure,

Properties, and Determination; Tannins and

Polyphenols

Further Reading

Bamforth C (1998) Beer: Tap into the Art and Science of

Brewing. New York: Insight.

Boulton C and Quain D (2001) Brewing Yeast and Fermen-

tation. Oxford: Blackwell.

Briggs DE, Hough JS, Stevens R and Young TW (1981)

Malting and Brewing Science. Volume 1: Malt and

Sweet Wort. London: Chapman and Hall.

Hornsey IS (1999) Brewing. London: Royal Society of

Chemistry.

Hough JS, Briggs DE, Stevens R and Young TW (1981)

Malting and Brewing Science. Volume 2: Hopped Wort

and Beer. London: Chapman and Hall.

Hughes PS and Baxter ED (2001) Beer: Quality, Safety

and Nutritional Aspects. London: Royal Society of

Chemistry.

Kunze W (1996) Technology: Malting and Brewing. Berlin:

VLB.

Lewis MJ and Young TW (1995) Brewing. London: Chap-

man and Hall.

MacDonald J, Reeve PTV, Ruddlesden JD and White FH

(1984) Current approaches to brewery fermentations.

In: Bushell ME (ed.) Progress in Industrial Microbiology,

Vol. 19: Modern Applications of Traditional Biotech-

nologies. Amsterdam: Elsevier.

Moll M (1991) Beers and Coolers. Andover: Intercept.

tbl0002 Table 2 Order-of-magnitude composition of a typical pilsner

beer

Component Typical level (mg l

1

)

Original wort gravity 120 10

3

Ethanol 40 10

3

Total carbohydrates 30 10

3

Glucose 150

Fructose 30

Sucrose 5

Maltose 1500

Maltotriose 2000

Dextrins derived from starch 24 10

3

b-Glucan 350

Pentosan 50

Protein 5000

Amino acids 1100

Thiamin 0.3

Riboflavin 0.4

Vitamin B

6

0.6

Pantothenic acid 1.5

Niacin 8.0

Biotin 0.01

Vitamin B

12

0.0001

Folic acid 0.2

Potassium 500

Sodium 30

Sulfate 200

Chloride 200

Organic acids (acetic, pyruvic,

citric, succinic, malic, lactic, etc.)

700

Polyphenols 150

Iso-a-acids 30

Sulfur dioxide 4

Carbon dioxide 5 10

3

Nucleotides and nucleosides 300

Glycerol 1500

Higher alcohols 100

Ethyl acetate 15

Iso-amyl acetate 1

Acetaldehyde 5

Essential oils from hops <1

Dimethyl sulfide 0.06

Total organic sulfur compounds <1

BEERS/Chemistry of Brewing 447

Microbreweries

A Nothaft, BrewTech Servic¸ os Ltd, Jacarepagua

´

-Rio

de Janeiro, Brazil

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 Although the term ‘microbrewery’ strongly suggests a

small-scale beer production plant, which is usually

true, the microbrewery activity is actually what

makes the difference in comparison with a large-

scale beer factory. A microbrewery is a driving force

in different marketplaces to reintroduce or, even more

often, to develop many different types of beer with

varying flavors. Tradition and diversity are key words

when describing specialty beers, which once was de-

fined by Charlie Papazian with the following state-

ment.

0002 Beer is an expression of the human endeavor of living.

We use science as a tool to create it, but its essence is and

always will be a form of art expressing the variety of the

world’s lifestyles. The diversity of the world’s food, bev-

erages (other than beer), art, religion, music, clothes

offer a great deal of varietal choice and contribute to

the quality of life. Beer belongs to this list. The variety of

specialty beers currently produced by small breweries

and brewpubs create the opportunity for the beer indus-

try to join global trends in offering diversity while also

enhancing the image of beer.

History

0003 After World War II, the scenario in the brewing indus-

try world-wide began to change with the formation of

large national breweries that, through the acquisition

of regional breweries and the consolidation of the

production sites as well as the product lines, strongly

influenced the marketplace. In England, this consoli-

dation happened during the 1960s and 1970s when

six national operating breweries were formed as a

result of the concentration of the production that

changed the industry and the way in which beer was

marketed.

0004 In 1971, four men, Jim Makin, Bill Mellor, Michael

Hardmann, and Graham Lees, unhappy with the

changes in the beer industry, especially with the fact

that they could no longer drink beers with traditional

flavor, decided to create a movement aimed at

changing this tendency. Initially, an association,

named ‘The Campaign for the Revitalization of Ale,’

shortly after renamed ‘Campaign for Real Ale’

(CAMRA) set the starting conditions for the micro-

breweries on the way we know them today.

0005In the late 1970s, interest in cask ales was regained,

and national breweries started to produce different

brands, encouraging regional brewers to maintain

efforts in producing the traditional beers. These

changes and the response from the consumers were

the catalyst for a wave of microbreweries in the early

1980s.

0006The success of CAMRA in England was a starting

point for similar international activities. Soon after,

CAMRA Canada was created, and the English

CAMRA become one of the members of the Euro-

pean Beer Consumer’s Union acting in the European

Parliament.

0007In Canada, where beer production was extremely

consolidated and the industry had to deal with strong

legal restrictions for production and commercializa-

tion, the major activity of the organization was to

legalize home brewing and the brewpubs.

0008In the USA, the driving organization was the

American Home Brewer’s Association, active since

the early 1980s, providing information and promot-

ing beer culture. This organization evolved to the

Association of Brewers, which is an educational and

trade association, still loyal to the initial motivation

of promoting beer culture, through their publications,

technical discussions on forums, conferences, and ex-

positions, as well as beer festivals such as The Great

American Beer Festival and, more recently, the World

Beer Cup.

tbl0001Table 1 Major beer types and styles

Type Style

Ale Belgian Witbier; German Weissbier; Dunkel-weizen;

Weizenbock; Berliner Weisse; lambic; Gueuze; Faro;

Kriek; Framboise

Sweet Stout; Oatmeal Stout; Dry Stout; Imperial Stout

Porter

Pale Mild; Dark Mild; Bitter; Best Bitter; Strong Bitter;

Brown Ale; Old Ale; Irish Red Ale; Scotch Ale;

Belgian Brown; Pale Ale; India Pale Ale; Belgian

Ales; Saisons; Trappisten; Altbier; Ko

¨

lsch; American

Ale; Cream Ale; Barley Wine

Lager Pilsener; Dortmunder; Export; Strong Lagers;

American Malt Liquor

Vienna; Ma

¨

rzen; Oktoberfest; Amber; Red Lager

Munich Pale; Munich Dark; Dark Bock; Pale Bock;

Double Bock

Special Fruit Beers

Chilli Beers

Honey Beers

Spiced Ales

Smoke Beers

Stone Beers

California Common

448 BEERS/Microbreweries

Beer Styles

0009 Diversity is the driving force for microbreweries, and

many different types of beer have been offered to

the public. Some would certainly have disappeared

if microbrewery activity did not exist, being found

only in history books. Additionally, the segment is

constantly introducing new styles of beers reflecting

the evolution of the market and technology.

0010 Usually, beers are divided into ales and lager, dis-

tinguished by the fact that ales have a fruity aroma

and flavor, and lagers are smoother and crisper. Also,

some beers are made using specific techniques and

ingredients, rendering their classification as ‘specialty’

beers, and they can be either ales or lagers.

0011 Table 1 lists the major types of beer; note that they

may have additional differentiations depending on

local conditions in different marketplaces around

the world.

Microbrewery Operation

0012 The size of the microbrewery plant size varies

according to the type of beer being produced, as

detailed in Table 2. Differences in plant size also

entail different methods of processing and quality

control. In larger plants, the same standards as those

in major breweries apply. Measurements to insure

that potential processing deviations can be identified

and corrected before they can affect the quality of the

final product are mandatory.

0013In microbreweries, where usually just a small

number of tanks are in use at a given time, and the

products are in different stages of process, a com-

pletely different approach for quality control is neces-

sary. The brewer has to focus on all precautions

necessary during the process to guarantee that the

product meets the desired standards. This is a relevant

difference between microbreweries and large-scale

production.

0015Looking further at the personal skills needed to

manage the different types of breweries, people in-

volved with microbreweries are usually individuals

tbl0002Table 2 Characteristics of microbreweries

Brewpub Most of the production is dedicated for in-

house sales

Microbrewery Produces for external sales in a reduced

geographical area

Regional brewery Produces for external sales in a larger

geographical area

Contract brewing The company develops the product formula,

merchandising and sales, and production

is hired from a third party company

fig0001 Figure 1 (see color plate 8) View of the brewhouse in a microbrewery.

BEERS/Microbreweries 449

who constantly like to face new challenges. They are

involved in the operation in all different aspects, often

being involved at different stages, from providing the

resources for brewing to sales or technical support in

the marketplace, and are often keen to play an active

part in developing a new beer formulation.

0016 This does not mean that they are better brewers

than those running large breweries. Large brewery

professionals gain their motivation by managing

such a complex structure involved in the beer produc-

tion.

0017 A plant showing the brewing house of a micro-

brewery is presented in Figure 1.

Quality Control

0018The construction of a laboratory with sufficient cap-

acity to run all necessary analyses to control all

phases of the process can easily double the cost of

the investment made in a microbrewery, and, as dis-

cussed previously, this will not insure the quality of

the final product. This means that strict control of the

process, by recording and evaluating processing data

and also by sensory evaluation of all process steps,

will contribute effectively to a successful quality

control.

0019Table 3 lists the recommended control tasks for the

operation of a small-scale microbrewery.

tbl0003 Table 3 Recommended tasks for quality control in a microbrewery

Processstep Minimallevelof control

Raw materials

Water Sensorial evaluation before every use and periodical external evaluation

Malt Sensorial evaluation, malt analysis from the supplier, and periodical external evaluation

Adjuncts Sensorial evaluation (hot water extract) and supplier analysis

Wort production

Raw material addition Weigh control

Malt grist Visual evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Water addition Volume control

Saccharification Iodine test

Evaporation rate Calculation

Production yield Calculation

pH Determination

Break formation Visual evaluation

Bitterness Sensory evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Color Visual evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Wort clarity Visual evaluation

Wort cooling/aeration

Cooling temperature Temperature control during the whole process

Process time Record time needed to cool

Oxygen intake Visual evaluation of the wort after the oxygen intake

Terminal load on wort Total time the wort was kept over 85

C, measured from the filling of the kettle to the final of the wort

cooling

Ye a s t d o s i n g

Yeast control Check flavor and appearance of the yeast, frequent renewal, and periodical microbiological control

Yeast storage Control how long yeast was stored between brews

Dosing volume Weight of yeast added to fermentation

Wort clarity Visual evaluation

Fermentation/aging

Extract reduction Record the extract reduction against the fermentation time

pH Check the pH on the end of fermentation and aging

Time/temperature/pressure Record the process parameters

Diacetyl Sensorial evaluation at the end of fermentation and aging

Cells in suspension Visual evaluation at the end of fermentation and aging

Oxygen intake Preventive operational procedures

Filtration/packaging

Appearance Visual evaluation of the brightness of the beer

Carbonation Sensory evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Foaming Visual evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Alcohol/extract Control with a saccharometer; although the analysis is not correct, it gives indications about

fluctuations. Periodical external evaluation

pH Control of the final product. Deviations are strong indicators of microbiological contamination

Bitterness Sensory evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Diacetyl Sensory evaluation and periodical external evaluation

Oxidation Sensory evaluation and periodical external evaluation

450 BEERS/Microbreweries

Perspectives

0020 Microbrewing has become a reality in most countries,

mainly due to the diversity of products offered to

consumers in general and to beer lovers in particular.

It has become a well-established segment of the

brewing industry in Europe, North America, Asia,

and Oceania. However, in South America and Africa,

this tendency has not yet achieved the same degree of

development. Clearly, there is potential for growth,

and it is anticipated that the formation of many new

microbreweries around the world will introduce a

variety of products and flavors to beer consumers.

See also: Beers: History and Types; Raw Materials;

Chemistry of Brewing; Biochemistry of Fermentation

Further Reading

Beer Seller’s Guide (1997) Institute for Brewing Studies.(ib-

s@aob.org)

Brewery Planner (1996) Brewers Publications.

Daniels R (1996) Designing Great Beers. Brewers Publica-

tions.

Eschenbach R (1993) Gasthausbrauerein. Verlag Hans Carl

Getra

¨

nke-Fachverlag.

Evaluating Beer (1993) Brewers Publications.

Jackson M (1988) The New World Guide to Beer. Courage

Books.

Papazian C (1998) Zymurgy, The Best Articles and Advice

from America’s # 1 Home Brewing magazine. Avon

Books.

Protz R (1995) The Ale Trail. Eric Dobby.

BEHAVIORAL (BEHAVIOURAL) EFFECTS OF

DIET

D A Booth, University of Birmingham, Edgbaston,

Birmingham, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Nutritional Effects on Behavior

0001 Behavior other than eating and drinking can be influ-

enced by physiological effects of the constituents of

foods and beverages. Indeed, consumers’ attributions

of effects on their subjective feelings or objective

performance appear to be among the major determin-

ants of the acceptance or refusal of certain items of

the diet. This aspect of the many relationships among

food, nutrition, and behavior is the topic of this

article.

Scientific Study of Effects of Diet on

Behavior

0002 The possible influences of diet on behavior have

attracted a considerable amount of public and pro-

fessional attention in recent years, and yet reliable

scientific information on such effects remains very

limited.

0003 This is partly because studies claiming positive

findings are often open to serious criticism of their

design and also of the theory behind them. Even

arguably supportable findings have frequently failed

to be substantiated after some years, at least on the

scale initially claimed. A field that acquires a dubious

reputation, or at best an air of scientific intractability,

will naturally have difficulty attracting much good

research. Nevertheless, definite scientific progress

could be made by close collaboration among social

cognitive psychologists, applied nutritionists, and

food technologists.

0004The measurement of behavioral performance or

experiences is not the real difficulty in studying diet-

ary effects on behavior, despite a widespread miscon-

ception to the contrary. Even the answers to questions

about personal viewpoints, which seem such ‘soft’

data to biologists and chemists, can be shown, by

the well-established criteria of multivariate psycho-

metrics, to reflect underlying determinants. Such ad-

equately scaled instruments provide valid and reliable

expressions of differences in emotional state and in

judgments of one’s own ability. Sound measurements

of intellectual performance, such as ability to concen-

trate or remember, or indeed physical performance,

such as athletic endurance, can be constructed by

cognitive or exercise scientists at least as easily as

self-ascription scales such as mood or ability.

0005The greatest difficulties arise in the design and

interpretation of investigations of real-life psycho-

logical phenomena and, indeed, in measuring the

composition of the everyday diet as well. As in any

other area of science, effective research requires a

good theoretical grasp of the mechanisms involved

and hence of the methods for obtaining evidence of

their operation. There are no standardized tests for

BEHAVIORAL (BEHAVIOURAL) EFFECTS OF DIET 451

effects of diet on behavior and there never will be,

any more than there can be standardized tests for

dietary effects on children’s growth or for consumer

perception of food quality.

0006 Hence what follows is an impressionistic sketch

of the theoretical issues of how diet might affect

behavior, with brief comments on the current state

of evidence for the mechanisms involved. Detailed

reviews referring to original studies are included

in the Further Reading section.

Long-Term Effects of Diet on Behavior

0007 There are broadly speaking two ways in which con-

stituents of the diet could have long-term psycho-

logical effects. They may affect the general physical

growth or deterioration of the nervous system. Alter-

natively, diet might permanently affect the function-

ing of the brain, via short-term effects on changes

within specific neural connections that have long-

term psychological consequences.

Brain Development

0008 The nerve cells in the human brain have virtually all

been formed prior to birth. Considerable elaboration

of interneuronal connections occurs postnatally, how-

ever. Maternal nutrition might therefore affect the

fetus or the breast-fed infant. Nevertheless, the brain

is very effective at extracting essential nutrients from

the blood supply and is not susceptible to over-

development. Hence there is reason to think that

only metabolic disorder or extreme deficiency in the

diet is liable to prejudice development of the brain.

0009 In the rare inherited metabolic disorders, the accu-

mulation of unusual catabolites damages the brain

unless prevented by dietary or genetic engineering.

As well as neurological disorders, more or less severe

learning difficulties (mental handicaps) can result.

(See Inborn Errors of Metabolism: Overview.)

0010 Possibilities under study include psychological

sequelae of neurological defects, prematurity or very

low birth weight, to which maternal deficiency (such

as in folic acid) might contribute. There is concern

that some fatty acids in breast milk may be needed in

infant milk formulae, at least in premature babies,

in order for the brain to develop to full intellectual

potential.

0011 Energy–protein deficiency early in childhood is

associated with slow intellectual development. It is

difficult to disentangle effects of malnutrition and

disease on brain growth from functional handicaps

arising from effects of economic and social disadvan-

tage. Nutritional supplementation and psychosocial

stimulation exert separate effects. In addition, school

failure in low-income areas is associated with missing

breakfast. However, regular provision of supple-

ments or breakfasts can be an important environ-

mental change, aside from its physiological effects.

(See Breakfast and Performance; Protein: Deficiency.)

Brain Damage

0012Nutritional factors have repeatedly been proposed for

schizophrenic and other psychiatrically diagnosed

disorders. None has yet been substantiated, however,

when subjected to controlled investigation. Thiamin

deficiency produces neurological symptoms, and lack

of this and other B vitamins is generally considered

to contribute to some encephalopathies that involve

several memory defects. Therapeutic effects of sup-

plementation remain to be established. (See Thiamin:

Physiology.)

0013Toxic contaminants of the diet may damage the

brain, with psychological sequelae. Nevertheless, no

long-term psychological effect of the present dietary

levels of residues, heavy metals, etc., has been estab-

lished to date. Ingestion of flakes of paint or contam-

inated dust can contribute to an accumulation of lead

in the brain but this generally results from hands or

objects being brought to the mouth, not from dietary

consumption. (See Heavy Metal Toxicology.)

Short-Term Mediation of Long-Term Effects

0014Long-term psychological effects of dietary consti-

tuents on children, such as those on intelligence

quotient (IQ), personality, or behavior disorders, are

likely to be mediated by acute psychological effects of

the daily diet. For example, if school performance

were permanently improved by regular provision of

breakfast, it could be because each meal facilitated

learning that morning.

0015Additives and hyperactivity Feingold’s initial hy-

pothesis that intolerances to food additives such as

colorings cause widespread behavioral problems in

children was narrowed at an early stage to tartrazine

and salicylates. Much subsequent investigation has

established the very low incidences of food intoler-

ances and the infrequency and transience of proven

allergenic reactions to food proteins in young chil-

dren. Moreover, recent work has shown no system-

atic behavioral effect when a toxicological sensitivity

has been provoked. (See Food Additives: Safety;

Food Intolerance: Types; Food Allergies; Lactose In-

tolerance.)

0016Vitamins and IQ Several recent reports have pro-

vided data interpreted as supporting the hypothesis

that supplementation with one or more unspecified

vitamins and/or minerals prevents a supposed slow-

ing of the normal rise in nonverbal intelligence test

452 BEHAVIORAL (BEHAVIOURAL) EFFECTS OF DIET

scores (IQ) in schoolchildren whose diets are alleged

to be deficient in those micronutrients.

0017 As yet, however, there is no satisfactory evidence

that those whose IQ scores appear to respond to

supplements are deficient in micronutrients, because

the only relevant dietary data are the children’s diet-

ary records and these are likely to be confounded by

factors that influence scores in IQ tests. Furthermore,

children who are estimated to be consuming less than

recommended levels of a micronutrient generally

appear also to have inadequate energy intakes. The

accuracy of these records is therefore suspect. Alter-

natively, these children may be chronically hungry or

reacting to other sorts of deprivation. This might

account at least in part for the fidgetiness and appar-

ent lack of attention that have been reported in chil-

dren having the poorer dietary records, which in

turn could make for poor learning and hence slowed

development of performance in some IQ tests. (See

Energy: Measurement of Food Energy.)

0018 Another (not incompatible) hypothesis is that the

high sugar intake of some children might have acute

sedative effects. This could result in difficulty in

thinking clearly, so that the child becomes restless

when faced with an intellectual challenge. (See

Sucrose: Dietary Importance.)

0019 No biochemically sound mechanism has yet been

proposed by which moderate vitamin or mineral

deficiency could affect nonverbal learning. Theory is

hardly feasible in any case because, although some

speculations have been offered, the neural bases of

individual differences in human intelligence are as yet

unknown.

Short-Term Effects of Diet on Behavior

0020 The acute effects on behavior of a constituent of a

drink or even of the composition of a meal are

both theoretically and methodologically much more

accessible than chronic dietary effects. Even so, they

pose formidable multidisciplinary challenges to inves-

tigators, in design and analysis of characteristics of

the diets, the consumers and the situations to be

observed.

Design of Investigations

0021 The foods When the issue is physiological effects in

the brain, the postingestional effects of the diet must

be distinguished from its sensory effects. This is cru-

cial in principle because a flavor or texture may sug-

gest effects to the consumer (e.g., filling, nutritious,

junk food, luxury) that could confuse the search for

physiologically mediated effects. The distinction has

become demonstrably necessary in some cases, such

as reduction of distress – just the taste of sugar can

quieten a baby and raise the pain threshold. Hence

differences in dose of the hypothesized active con-

stituent must not be detectable to the subject. If

the agent cannot be swallowed in a capsule, demon-

stration of effective sensory matching or masking is

necessary. (See Sensory Evaluation: Sensory Charac-

teristics of Human Foods.)

0022For major constituents of the diet, the techno-

logical requirements to design unambiguous research

protocols may be so unusual and difficult as to be

impossible at reasonable expense. Experimental

cognitive psychology can provide a way round by

measurements that pick out the effects of sensorily

triggered expectations, but this demands sophisti-

cated design and analysis (and a modicum of good

luck).

0023The eaters Individuals may vary from one another

physiologically in susceptibility to a dietary factor.

They will certainly differ in prior experiences with

foods and drinks containing the component(s) of

interest.

0024Where the psychological effect being studied is

known to the public, and especially if it is commonly

sought or avoided, the effectiveness of a study is likely

to depend on designing and analyzing it around the

participants’ uses of items and the occasions when

they are consumed. This will not only help to accom-

modate differences in both physiology and experi-

ence; it can also enable differences to be exploited.

For example, disguised variations of a constituent,

around the level at which an individual normally

consumes it with the expectation of a relevant

psychological effect, are likely to be a more sensitive

design than the same levels imposed on everyone

tested, without regard to their normal expectations.

0025The test tasks and situations A psychological effect

may be wanted only in certain situations by a given

consumer. Indeed, the effect may only occur in spe-

cific circumstances. That can be because the effect is

part of conventional behavior and experience in those

circumstances or because the user personally dis-

covered something, when the conditions were right,

that the item could do for mood or performance.

It may well be crucial, therefore, that the setting

investigated and the state of mind of the research

participant are suited to the mood or performance

under study and that the behavioral tests measure

those particular benefits that each participant obtains

during normal use of the dietary item.

Alcohol

0026Alcoholic beverages have been an important part of

the diet in many cultures from time immemorial. The

BEHAVIORAL (BEHAVIOURAL) EFFECTS OF DIET 453

alcohol content is widely regarded as a source of good

cheer on social occasions and soothing or even emo-

tionally anesthetic at times of distress. However, in-

capacitating effects of alcohol are also well known, as

is the risk of problems from its continuous heavy use.

(See Alcohol: Metabolism, Beneficial Effects, and

Toxicology.)

0027 Neurophysiological evidence suggests that etha-

nol has psychoactive effects by acting on the g-

aminobutyric acid (GABA) receptor system at inhibi-

tory synapses throughout the nervous system. Such

neural inhibition is critical to the precision of infor-

mation processing. Thus the postingestional psycho-

logical effects of ethanol are likely to be protean. It

may be that all forms of fine control, including precise

physical movements (walking down a straight line),

vigilance against subtle dangers (crossing in front of

approaching traffic), and self-critical social perform-

ance (ethical inhibitions and fears for self-esteem), are

rendered less competent.

0028 However, ethanol has been regarded in animal

pharmacology as specifically anxiety-reducing at

subsedative doses. The benzodiazepines (such as

Valium), that also act on the GABA system, are used

as antianxiety agents, as well as muscle relaxants and

sedatives. Thus the neural actions of ethanol may

be more effective at reducing tensions than at incap-

acitating generally.

0029 Many of the effects of common levels of consump-

tion of alcoholic beverages on mood and social be-

havior appear to have at least as much to do with the

drinking situation as with neural actions of ethanol.

Merriment and perhaps sexual predation are what is

expected at parties; personal aggressiveness and van-

dalism became a norm for soccer fans, and gloom is

natural for the lone(ly) drinker. All these effects have

been seen in experimental studies, but there tend to

be large ‘placebo’ or expectancy effects too. It seems

that ethanol contributes some disinhibition or incap-

acitation but a participative spirit achieves the rest.

0030 The behavioral effects of ethanol in the diet are

therefore complex to investigate. The sensory qual-

ities of ethanol and the aftereffects of its ingestion on

bodily sensations and mental and physical abilities are

well known to experienced drinkers. This weakens

the interpretations of sophisticated experiments on

the behavioral effects of ethanol (as also for other

familiar substances).

0031 One example is the so-called ‘balanced placebo’

design. This has four conditions, two drinks with

ethanol and two without, where one of each pair is

stated by the investigator to contain alcohol and the

other is said not to. The presence and absence of

alcohol are supposed to be masked but, when the

sensory disguise is checked, it is often found to have

been ineffective. Furthermore, characteristic effects of

ethanol are liable to be noticed some minutes after

ingestion of the ethanol-spiked drink that was alleged

to be an alcohol-free drink. This is likely to provoke

an emotional reaction and to change the strategy in

the task set by the experimenter. An experienced user

not feeling the usual effects when the drink was

falsely said to contain alcohol is also likely to react

to that disparity but in a different way, perhaps more

disappointed than angry. Thus the effects on behavior

of stated and actual alcohol contents cannot be separ-

ated out by analysis of this two-by-two design on an

additive model: it is not balanced and placebo control

is impracticable (as generally for familiar psycho-

active substances). Detailed evidence is needed on

the cognitive processes after drinking more or less

alcohol with the normal approximate knowledge of

amount.

0032Traditional dose–response studies of behavioral

effects of alcohol are subject to similar problems,

even when the variations in alcohol content are not

detected during consumption and aftereffects are

hard to distinguish, e.g., within the lower range of

doses. Sensitive tests of psychomotor performance

can show deficits at low doses that are proportionate

to those at higher doses, thus justifying an argument

for a zero blood alcohol limit on drivers. However,

the consumer of a known amount of alcohol before

driving or working may pay closer attention to the

task and put extra effort into control and decision. In

some circumstances, such an effort can overcompen-

sate for the detrimental effect of ethanol, associating

a low dose with objectively improved performance.

Of course, such an effect should not be confused

with the personal belief that a little alcohol has im-

proved one’s performance, since that is liable to be an

illusion fostered by ethanol’s disruption of self-critical

abilities. Nevertheless, this phenomenon does illus-

trate how actively people use the effects of food

and drink; they are not just affected passively or

automatically.

Caffeine

0033Caffeine is thought to be able to act as a mild alerting

agent by blocking synaptic receptors for endogenous

adenosine, which is sedative. However, the experi-

mental literature on human behavior has been con-

fused by the use of large doses relative to those

obtained through normal coffee, tea, and cola drink-

ing, by differences between people in responsiveness

to caffeine, and in the benefits to performance or

mood habitually obtained from such drinks, and

by unrealistic tests for such benefits. (See Caffeine.)

0034In a study using normal doses, quite strong and

consistent effects of caffeine (at a dose as low as

454 BEHAVIORAL (BEHAVIOURAL) EFFECTS OF DIET