Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Huang HT (2000) Science and Civilisation in China, 6(v):

Fermentations and Food Science. Cambridge: Cam-

bridge University Press.

Lee C-H, Steinkraus KH and Reilly PJA (eds) (1993) Fish

Fermentation Technology. Tokyo, Japan: United

Nations University Press.

Pederson CS (1979) Microbiology of Food Fermentations,

2nd edn. Westport, CT: Avi Publishing.

Reddy NR, Person MD and Saluniche DK (eds) (1986)

Legume-Based Fermented Foods. Boca Raton: CRC

Press.

Rose AH (ed.) (1982) Economic Microbiology, vol. 7:

Fermented Foods. London: Academic Press.

Sherman PW and Flaxman SM (2001) Protecting ourselves

from food. American Scientist 89(2): 142–151.

Steinkraus KH (ed.) (1989) Industrialization of Indigenous

Fermented Foods. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Steinkraus KH (ed.) (1996) Handbook of Indigenous

Fermented Foods, 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Sudarmajdji S, Suparmo and Raharjo S (eds) (1998)

Reinventing the Hidden Miracle of Tempe. Jakarta:

Indonesian Tempe Foundation.

Wood BJB (ed.) (1998) Microbiology of Fermented Foods,

2nd edn. Glasgow: Blackie.

Fermented Meat Products

F-K Lu

¨

cke, Fachhochschule, Fulda, Germany

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Fermented meat products have been subjected to the

action of microorganisms or tissue enzymes so that

they are modified significantly in a desirable fashion.

They are subdivided into fermented sausages (prod-

ucts made from comminuted meat stuffed into

casings) and fermented unground meats. This article

provides basic information on the manufacture of

fermented meat products and on the factors affecting

their safety and quality.

Types of Fermented Meats

Fermented Sausages

0002Fermented sausages are manufactured from commin-

uted lean and fatty tissue, mixed with salt, spices,

sugar, and, in most cases, curing agents (nitrite, ni-

trate, ascorbate). Particularly in commercial produc-

tion, starter cultures are also added. The mix is then

filled into casings and subjected to a microbial fer-

mentation. Many, but not all varieties of fermented

sausages are subsequently aged to dry them and to

develop the desired sensory properties. Another

criterion for the classification of fermented sausages

is the surface treatment (e.g., smoking, mold growth).

Table 1 gives a classification of fermented sausages,

along with the definitions of terms used in this article.

0003An official classification of fermented sausages

is important to avoid misleading the consumer and

unfair competition between manufacturers. Different

parameters are used in different countries; however,

they are all more or less related to the degree of drying

and the percentage of high-quality raw material (lean

muscle tissue) in the formulation. For example, the

German Code of Practice (Leitsa

¨

tze) specifies the

minimum content of collagen-free lean meat for

different sausage varieties while key parameters in

France are the ratio between collagen and protein,

the fat content and the percentage of moisture,

based on fat-free dry matter.

Fermented Unground Meats

0004To produce aged hams and related raw cured meats,

salt is added by rubbing it on to the meat surface or by

immersing the cut into a brine or by injecting brine

tbl0001 Table 1 Classification of fermented sausages

Class Final water

activity

Total ripening time Use of smoke Mold growth

onsurface

Examples

Dry < 0.90 > 4 weeks No Yes Traditional Italian salami, French

saucisson sec

Dry<0.90>4weeksYes

a

YesTraditionalHungariansalami

Dry < 0.90 > 4 weeks Yes or no No German Dauerwurst

Semidry 0.90–0.95 < 4 weeks No Yes Various French and Spanish fermented

sausages

Semidry 0.90–0.95 Usually 10–20 days Yes (with exceptions) No Most fermented sausages in Germany,

the Netherlands, Scandinavia, USA

Undried 0.94–0.97 < 2 weeks Yes or no No German Teewurst, Spanish sobrasada,

Thainham

b

a

During fermentation.

b

Normally cooked before eating.

2338 FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products

into the tissue. Then, cuts are kept at low tem-

peratures (10

C or below) until the salt is evenly

distributed. During subsequent aging at elevated

temperatures (15–30

C), they not only lose some

moisture but are also tenderized by tissue proteases.

Only such aged products may therefore be termed

fermented. They are normally eaten raw, and include

raw (pork) ham, but also Italian coppa and some

products from beef muscle (e.g., Swiss Bu

¨

ndner-

fleisch, Turkish pastirma).

The Manufacture of Fermented Sausages

Choice and Comminution of Raw Material

0005 The microbiological quality of the raw material (lean

and fatty tissue) should be controlled by continuously

monitoring the temperature during meat handling

and transport, by visual inspection of shipments,

and by selecting suppliers following good hygienic

practice in slaughtering and butchering. For the

manufacture of fermented sausages, the pH of the

raw material should be 5.8 or lower because higher

pH values favor the growth of undesired or hazard-

ous acid-sensitive bacteria. Initial pH values of the

sausage mix between 5.8 and 6.0 may still be toler-

ated if a rapid onset and a sufficient rate and extent of

lactic acid formation are ascertained. To obtain prod-

ucts of good sensory quality and shelf-life, the fatty

tissue used should be low in polyunsaturated fatty

acids and peroxides. To minimize fat deterioration,

the material is usually chilled or frozen in order to

keep the temperature during comminution below

2

C, and exposure to oxygen should be minimized

during communition and filling.

Formulation and Filling

0006 By removal of oxygen and addition of salt, the normal

spoilage flora of aerobically stored fresh meat (mainly

pseudomonads) is suppressed. With few exceptions,

the target water activity (a

w

) of sausage mixes

is 0.955–0.965. This is mostly achieved by adding

30–35% fatty tissue (giving a moisture content of

about 50% in the mix) and 2.5–3.0% salt. Higher

initial a

w

values favor growth of Enterobacteriaceae

(including Salmonella) whereas at a

w

below 0.955,

acid formation by lactic acid bacteria may be too slow

to suppress Staphylococcus aureus reliably, a bacter-

ium which still grows well at this a

w

.

0007 For most semidry fermented sausages, nitrite is

used as curing agent at input levels between 100 and

150 mg NaNO

2

kg

1

, normally in combination with

300–500 mg sodium ascorbate per kg. Nitrite con-

tributes to the inhibition of Enterobacteriaceae early

in fermentation but has little effect on Staphylococcus

aureus and on lactic acid bacteria. Moreover, by

reacting with heme and nonheme iron, nitrite brings

about the development of the desired curing color and

curing aroma. Dry sausages are often made with ni-

trate rather than nitrite or with reduced input levels of

nitrite. Such products must be fermented at lower

temperatures. There is no need whatsoever to add

more than 150 mg sodium nitrite kg

1

, more than

300 mg potassium nitrate kg

1

, or to combine nitrite

and nitrate.

0008Carbohydrates are added to the mix to provide an

energy source for lactic acid bacteria. Addition of

0.3% glucose or another rapidly fermentable mono-

or disaccharide will enable the lactic acid bacteria to

lower the pH from 5.8 to 5.3 or below, which is

normally sufficient for microbiological safety. If the

initial pH of the mix is higher (5.8–6.0) and/or a

lower final pH is desired, the input of rapidly fer-

mentable sugar is increased to 0.5–0.8%. The acidu-

lant glucono-d-lactone (GdL) is only used for

products with a short shelf-life because many strains

of lactic acid bacteria ferment this compound to lactic

and acetic acid, and acetic acid interferes with reac-

tions leading to and stabilizing desired sensory prop-

erties. Also, use of excessive amounts of fermentable

sugars, in conjunction with insufficient drying and

elevated aging and/or storage temperature, results in

high levels of lactic and acetic acids, sometimes even

in pore formation and swollen packs due to CO

2

production by heterofermentative lactobacilli. Lacto-

bacilli may also contribute to the spoilage of fer-

mented sausage by forming hydrogen peroxide

which attacks heme compounds and polyunsaturated

fatty acids. This in turn leads to gray or greenish

discolorations and flavor defects, particularly if soft,

improperly stored fatty tissue has been used.

0009In addition to their effects on aroma and flavor,

some spices contain antioxidative compounds and

may, by means of their manganese content, increase

the rate of acid production during sausage fermenta-

tion.

0010During the 1970s and 1980s, it became common

practice to use starter cultures in industrial sausage

fermentations. Most commercial preparations con-

tain a combination of lactic acid bacteria with non-

pathogenic catalase-positive cocci. Such cultures have

also been shown to be useful for the manufacture of a

wide spectrum of traditional indigenous sausage var-

ieties on a small scale, and also replaced, to a large

extent, so-called back-slopping methods where a

fermented sausage from the previous batch is used

to inoculate the following batch. The disadvantage

of the latter method is that desired catalase-positive

cocci will tend to become diluted out, and strains with

undesirable metabolic properties may be selected.

FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products 2339

0011 Suitable starter bacteria must be sufficiently active

in the a

w

range between 0.93 and 0.96 and at

the fermentation temperature chosen (in Europe,

20–25

C), and must be able to ferment the sugar

added. To avoid excessive lag phases, resuscitation

times in sausage mix must be short. Obviously, they

must not be pathogenic or toxinogenic, and should

not form biogenic amines nor metabolites detrimental

to the sensory properties of the product.

0012 Use of lactic acid bacteria is important for the safe

production of rapidly fermented semidry sausages,

whereas at low ripening temperatures their effect is

small. Of the species of lactic acid bacteria that are

commercially available, Lactobacillus sakei strains

tend to acidify the sausages most rapidly, and to be

most competitive towards acid-sensitive bacteria and

other lactobacilli. Acidification rates of Pediococcus

pentosaceus and L. curvatus depend much on the

strain used, and may be equal to or higher than

those of L. plantarum and L. pentosus. P. pentosaceus

is often stated to form a milder aroma. In the temp-

erature range between 20 and 25

C, acid formation

by P. acidilactici is too slow to be of much benefit.

Suitable starters should thrive in the product while not

forming gas, hydrogen peroxide, biogenic amines, or

other compounds of sensory or toxicological concern.

0013 Starters containing catalase-positive cocci are of

most benefit to products prepared with nitrate, and

products to have a long shelf-life. Adding sufficiently

high levels (10

6

–10

7

g

1

) of nonpathogenic Staphylo-

coccus or Kocuria spp. largely eliminates the need for

growing these bacteria in the product by keeping the

pH in the permissive range (> 5.3). Strains of Staphylo-

coccus carnosus, S. xylosus, and Kocuria varians are

commercially available. Whether or not a yeast

(Debaryomyces hansenii/Candida famata) is useful

depends very much on the aroma note desired. Surface

inoculation with molds is advisable in the manufac-

ture of mold-ripened products. Mold starters must be

able to colonize the surface without sporulation and

without formation of mycotoxins or antibiotics.

Strains of Penicillium nalgiovense and P. chrysogenum

have been selected for sausage fermentation.

Fermentation

0014 Fermentation temperatures between 20 and 25

C are

most common in European-type sausage fermenta-

tion. For US-type summer sausage, higher tempera-

tures (up to 41

C) are used. Rapid onset and rates

of acid formation must be ascertained to suppress

pathogens such as Salmonella and Staphylococcus

aureus under these conditions. Some traditional prod-

ucts are fermented at lower temperatures for longer

times. Sausages expected to have a long shelf-life

should be fermented at lower temperatures in order

to restrict acid formation and to obtain maximum

activity of microorganisms that reduce nitrate and

are involved in the formation of aroma and flavor.

As pointed out above, fermentation temperature

must also be lowered if the initial a

w

is outside the

range between 0.955 and 0.965, if no nitrite is added,

or if the pH is not to drop below 5.3. For genuine

Hungarian salami, fermentation temperatures are as

low as 12

C.

0015Early after stuffing, residual oxygen is consumed

by meat enzymes, and oxygenated myoglobin is

turned into brownish metmyoglobin. Nitrite acceler-

ates metmyoglobin formation but slows down the

former process. Subsequently, acid formation starts,

and catalase-positive cocci reduce nitrate to nitrite.

Acid favors the reaction of nitrite with metmyoglobin

to give rise to pink nitric oxide myoglobin. Residual

nitrite is reduced by the sausage microflora. As acid

formation continues, the pH drops to about 5.3. At

this pH, growth of acid-sensitive bacteria, including

catalase-positive cocci, are inhibited, and the water-

binding capacity of the mix becomes minimal. Then,

fermentation is usually slowed down by adjusting the

temperature to about 15

C and by lowering the rela-

tive humidity (RH) in the chamber, thus reducing the

a

w

of the sausages. The flavor of sausages consumed

after little or no aging is dominated by lactic acid and

some acetic acid, and by compounds determining the

flavor of fresh meat.

Surface Treatment and Aging

0016After fermentation, most sausages produced in cen-

tral and northern Europe are smoked. This leads to

inhibition of microbial growth on the surface and to a

delay of oxidative changes. On unsmoked products

common in France and Italy, but also in Spain and

Switzerland, a surface bloom develops, mainly con-

sisting of salt-tolerant yeasts (e.g., Debaryomyces

hansenii) and of molds. This layer also protects the

product from oxygen and facilitates drying.

0017Sausages are usually aged at 12–15

C. The climate

should ensure a slow but steady removal of moisture

from the sausages and prevent undesired mold

growth on the surface while avoiding uneven drying

of the product and concomitant undesired changes in

appearance and texture. Hence, the RH in the chamber

is gradually lowered to about 75–80%, and air vel-

ocity is adjusted to about 0.1 m s

1

. Most sliceable

semidry fermented sausages are dried to moisture con-

tents of about 40%, which corresponds to a weight

loss of about 18% and an a

w

value around 0.93. Dry

sausages (a

w

< 0.90) have 35% moisture or less, cor-

responding to a weight loss of 25% or more. Obvi-

ously, more water must be removed if the formulation

includes less fat and more lean meat than common.

2340 FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products

0018 During aging, the flavor and aroma characteristics

for fermented sausages are formed and stabilized.

Lipids are precursors of many unbranched aldehydes,

2-alkanones, and short-chain unbranched fatty acids.

The process involves tissue lipases, autoxidation

reactions, and the transformation of the reaction

products by microorganisms. Use of nitrite results in

partial inhibition of oxidative changes of lipids, and

in a shift in the reaction products. Tissue proteases

split proteins into peptides that are subsequently

transformed by microorganisms into amino acids

and branched-chain volatile fatty acids. Ethyl esters

also contribute to sausage aroma. Sufficient activity

of catalase-positive cocci is important for the devel-

opment and stabilization of the desired sensory prop-

erties. To obtain a sausage with full aroma and flavor,

it is therefore important to limit rate and extent of

acid formation and to age the product for a minimum

of several weeks. If undesired mold growth is

prevented, oxidative changes in the lipid fraction

(rancidity) limit the shelf-life of most semidry or dry

sausages.

Safety of Fermented Sausages

0019 Hazards to be controlled during manufacture of

fermented sausages are listed in Table 2 and analyzed

on the basis of exposure, severity of disease, and

epidemiological data, i.e., reports on outbreaks due

to the consumption of fermented sausage.

Preventive Measures and Critical Limits to Control

Microbiological Hazards

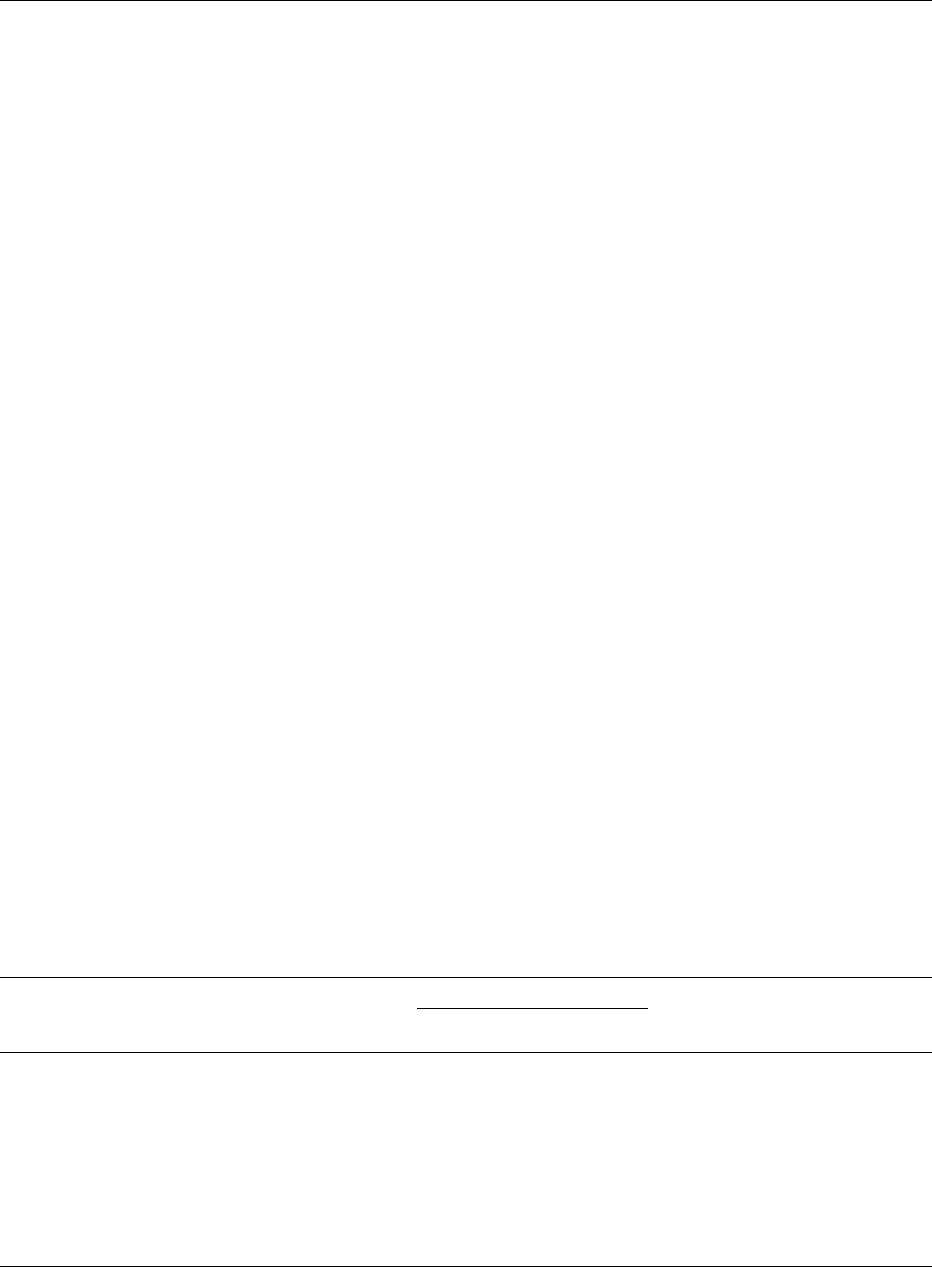

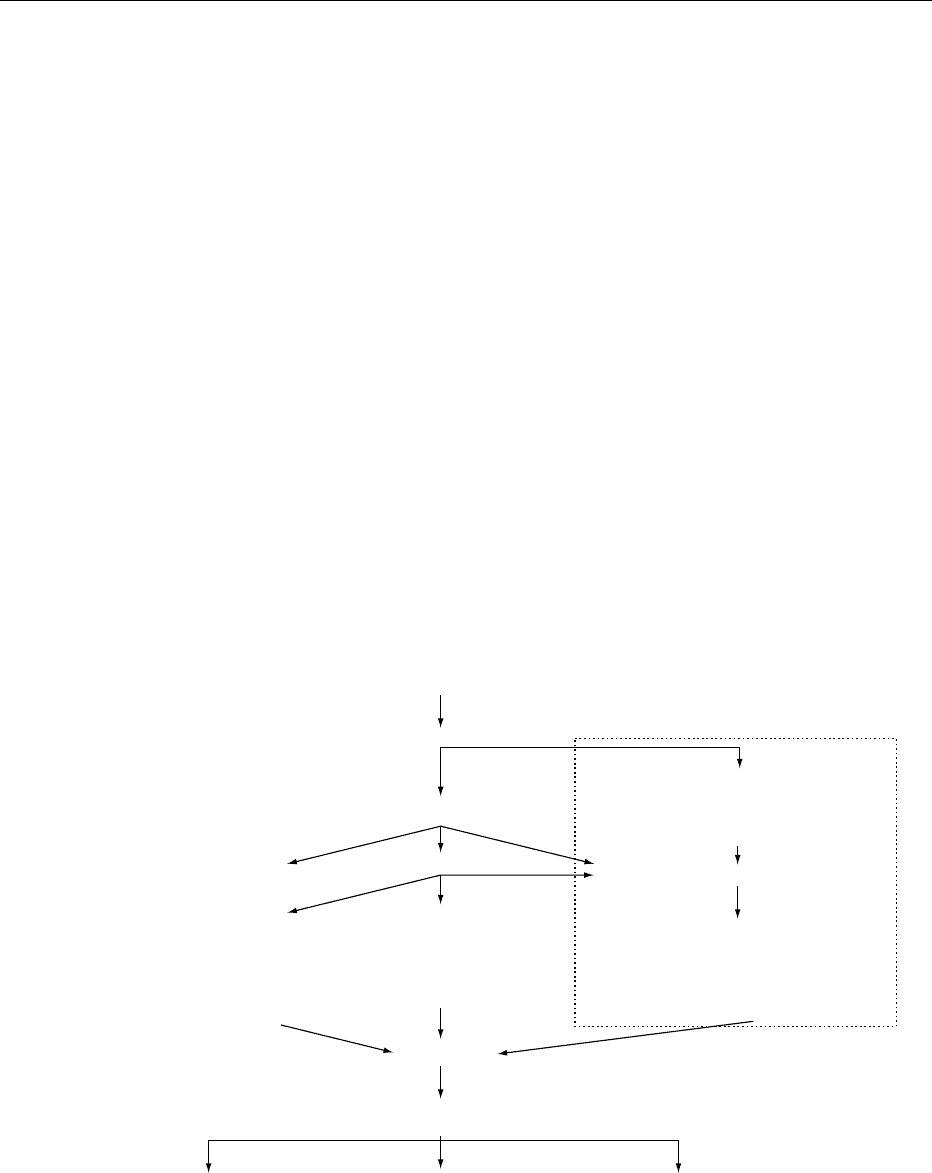

0020 Figure 1 provides a flow diagram of the manufactur-

ing process and includes preventive measures against

growth of Salmonella and other pathogenic Entero-

bacteriaceae and Staphylococcus aureus.

0021The critical limits given have been validated by

commercial practice. However, they do not cover

the whole range of types of fermented sausages.

Lowering one hurdle (e.g., addition of less salt or

curing agents) must be compensated for by fortifying

another hurdle (e.g., by increasing the rate of acid

formation). Experience shows that incriminated

products have been either fermented at too high

temperatures without starters and with nitrate rather

than nitrite, or have been eaten after a very short

fermentation with little, if any, drying.

0022In contrast to Salmonella, the infective dose

of enterohemorrhagic strains of Escherichia coli

(EHEC) is low. Hence, sausages containing EHEC

are a hazard to the consumer, even if growth of

EHEC is reliably suppressed during fermentation.

The presence of EHEC in meat, especially in beef

and lamb, cannot be excluded, and the extent of

destruction of EHEC during sausage ripening ranges

from less than 1 log (in undried products) to 3–4 log

(in smoked dry products of low final pH). Hence, it is

crucial to minimize fecal contamination of beef and

lamb carcasses during skinning and evisceration.

Moreover, beef- or lamb-containing raw sausages

with short ripening times should be excluded from

the diet of small children (the main risk group for

hemorrhagic colitis and its life-threatening sequela

disease, hemolytic–uremic syndrome).

0023Protein degradation by tissue enzymes during

prolonged storage of raw meat, in conjunction with

growth of psychrotrophic lactic acid bacteria capable

of histidine decarboxylation (in particular, certain

strains of Carnobacterium spp. and of Lactobacillus

curvatus), appears to be the main risk factor for the

formation of biogenic amines. Hence, the formation

of these amines can be minimized by proper selection

of raw materials and starter cultures.

tbl0002 Table 2 Analysis of microbial hazards during the manufacture of fermented sausages

a

Agents Growthpotential

during

fermentation

Prevalence

in 25 -g

samples

Minimum celldensity for disease Severity

of disease

Epidemiological

evidence

Risk

priority

Normal Risk groups

Salmonella Low 0.1–5% Medium Low Low Yes High

Enterohemorrhagic

Escherichia coli

Low 0.001–0.1% Low Very low High Yes High

Listeria

monocytogenes

Very low 10% Probably high Low High No Moderate

Staphylococcus aureus Low 10% High (toxin formation in product) Very low Yes Moderate

Yersinia enterocolitica

b

Low <1% Probably high Low No Low

Bacteria forming

biogenic amines

Yes

c

Yes High (toxin formation in product) Very low No Low

Molds forming mycotoxins Low Low High (toxin formation in product) Chronic No Low

d

a

Spore-forming bacteria and Campylobacter jejuni are no significant hazard.

b

Pathogenic serotypes.

c

Strains of lactic acid bacteria.

d

Mainly relevant for mold-fermented types.

FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products 2341

Process steps for: Preventive measures for:

Smoked

types

Mold-

ripened

types

Selection of raw

material

Chilling/freezing

Comminution and

mixing

Salt (NaCl)

Curing

agents

Sugars

c

Starters

d

Spices

Filling

Casings

Starter

Surface

inoculation

Good microbial quality; documented temperature

history; pH # 5.8 (6.0

a

)

Meat temperature < 2 8C

Target water activity (a

w

) 0.955-0.965

100-125 mg

NaNO

2

kg

-1

b

0.5-0.8%

LAB +cat

+

Proper cleaning and preparation of natural casings

Use of tested/certified mold culture

LAB +cat

+

None required

0.3-0.5% 0.3%

NaNO

2

kg

−1

b

KNO

3

kg

−1

or none

50−70 mg < 300 mg

Additives

Semidry or

undried

(spreadable)

sausages

Dry and/or mold-

ripened sausages

Traditional dry

sausages

Fermentation

20-25 8C, 2-3

days,

target pH < 5.3

Smoking

Aging/

drying

Storage

Undried

Aging

< 3 days,

< 15 8C,

a

w

> 0.95

< 7 8C < 15 8C < 25 8C< 25 8C

< 15 8C,

70−80%

RH

f

:

Target a

w

c. 0.93

10-15 8C

e

70−80% RH

f

:

Target a

w

# 0.90

# 10 8C,

70−80% RH

f

:

Target a

w

# 0.90

Semidry

18-22 8C, target

pH # 5.3 (c. 3

days)

15-18 8C,

2 days

fig0001 Figure 1 The manufacture of major types of fermented sausages, and measures preventing growth of Salmonella, Staphylococcus

aureus, and Listeria monocytogenes. Critical limits at critical control points are printed in bold.

a

Adjustment of sugar addition and

fermentation conditions may be necessary.

b

With maximum 500 mg sodium ascorbate kg

1

.

c

Rapidly fermentable by the starter used:

0.8% should be used if meat pH is above 5.8.

d

LAB, lactic acid bacteria; cat

þ

, catalase-positive cocci (Staphylococcus, Kocuria). Starters

must be active at the fermentation temperature selected.

e

For mold-ripened products, temperature should be lowered to about 10

C

after 2 days of fermentation.

f

RH, relative humidity. Adjustment depends on pH and a

w

of sausage. Modified from Lu

¨

cke FK (2000a)

Fermented meats. In: Lund BM, Baird-Parker AC and Gould GW (eds), The Microbiological Safety and Quality of Food, pp. 420–444.

Gaithersburg: Aspen.

2342 FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products

0024 Mold growth on fermented sausages may be

inhibited by appropriate control of temperature and

RH during aging, storage, and distribution, by ex-

cluding oxygen from the packages, and/or by surface

treatment with smoke, permitted antifungal agents,

or waxes. Products to be mold-ripened should be

inoculated with a suitable nontoxic mold strain and

dried at temperatures below 15

C.

0025 Viruses already present in livestock at the time of

slaughter normally do not affect humans. However,

since these viruses are, as a rule, only slowly inactivated

during sausage ripening, fermented meats should, like

unprocessed meats, not be exported from areas where

viral diseases of meat animals prevail. Viruses patho-

genic for humans also retain their infectivity during

sausage fermentation, and, as in all cases where food

is handled, contamination of the food by human feces

must be avoided by proper personal hygiene.

0026 Parasites (protozoa, nematodes, tapeworms) that

may occasionally escape detection during inspection

of the animals and their meat at the slaughterhouse

are inactivated by low a

w

values as prevail in dried

sausages, and are reliably absent from meats dried to

a

w

values of 0.90 or below. Parasites are also unlikely

to survive the a

w

and pH values typical for most

semidry sausages. However, in the USA, pork is not

generally inspected for the absence of Trichinella, and

regulations stipulate that semidry and undried fer-

mented sausages must be made from meat which

has been stored frozen, or be heated to 58.3

C

(137

F).

The Safe Manufacture of Fermented

Unground Meats

0027 For the manufacture of raw hams and comparable

products, it is very important to select cuts of normal

pH (5.8), particularly for large pieces; otherwise,

salting proceeds slowly, and the risk of growth of

pathogens during the salting process increases unless

special precautions are taken.

0028 In contrast to fermented sausages, changes in lipids

are of little significance, and the microbiology and

sensory characteristics of raw ham are little affected

by nitrite. Hence, many aged products with long

shelf-life are made with nitrate rather than nitrite, or

with no curing agent at all.

0029 The method of salting depends on the type of

product and on local tradition. Injection of brine is

uncommon in the manufacture of products to be aged

and dried. Dry salting proceeds only slowly, but is

preferred for most high-quality, expensive products.

The meat is salted until sufficient salt has diffused

into its core. During this period and the following

equilibration time, the temperature must be low

(5

C in the core of large pieces) in order to prevent

growth of any psychrotrophs (including nonproteoly-

tic Clostridium botulinum) possibly present in the

interior of the meat. Target a

w

is 0.96 or below in

all parts of the cut. The time required depends on the

geometry of the cut, the concentration gradient of

salt, and the ratio between meat and brine. There is

little microbial activity in the ham under these cool,

salty conditions. However, in recycled brines, a popu-

lation may develop containing halotolerant psychro-

trophic Gram-negative bacteria, such as Halomonas

spp. Using such brines may improve the sensory qual-

ity of nitrate-cured hams because Halomonas, unlike

other bacteria, actively reduces nitrate under the con-

ditions prevailing in concentrated curing brines, and

may also form aroma precursors.

0030After salting and equilibration, excessive salt and

moisture are removed from the surface. To prevent

growth of Staphylococcus aureus, this should be

performed at 18

C or below. Subsequently, the hams

may be smoked (e.g., Westphalian ham) or not (e.g.,

Parma or Serrano ham), and dried to the desired a

w

.

Once they are microbiologically stable, top-quality

hams are further aged at higher temperatures

(25–30

C) to make them very tender and tasty. If the

surface is kept moist enough, a surface bloom of cata-

lase-positive cocci, molds, and yeasts may develop and

affect the sensory properties of the ham; otherwise,

there is little, if any, role of microorganisms in the

development of aroma and flavor during aging.

See also: Escherichia coli: Food Poisoning; Food

Poisoning: Classification; Tracing Origins and Testing;

Statistics; Economic Implications; Hazard Analysis

Critical Control Point; Lactic Acid Bacteria; Listeria:

Properties and Occurrence; Meat: Preservation; Eating

Quality; Analysis; Nutritional Value; Hygiene; Extracts;

Mycotoxins: Occurrence and Determination; Starter

Cultures; Zoonoses

Further Reading

Campbell-Platt G and Cook PE (eds) (1995) Fermented

Meats. London: Blackie Academic and Professional.

Demeyer DI (1992) Meat fermentation as an integrated

process. In: Smulders FJM, Toldra

´

F, Flores J and Prieto

M (eds) New Technologies for Meat and Meat Products,

pp. 21–36. Nijmegen: Audet Tijdschriften.

Geisen R (1993) Fungal starter cultures for fermented

foods: molecular aspects. Trends in Food Science and

Technology 4: 251–256.

Hammes WP and Knauf HJ (1994) Starters in the process-

ing of meat products. Meat Science 36: 155–168.

Incze K (1998) Dry fermented sausages. Meat Science

49(suppl. 1): S169–S177.

Jessen B (2000) Meat starter cultures and meat product

manufacturing. In: Francis FJ (ed.) Wiley Encyclopedia

FERMENTED FOODS/Fermented Meat Products 2343

of Food Science and Technology, pp. 1614–1622. New

York: Wiley.

Leistner L and Gorris LGM (1995) Food preservation by

hurdle technology. Trends in Food Science and Technol-

ogy 6: 41–46.

Lu

¨

cke FK (1998) Fermented sausages. In: Wood BJB (ed.)

Microbiology of Fermented Foods, 2nd edn, pp.

441–483. London: Blackie Academic and Professional.

Lu

¨

cke FK (2000a) Fermented meats. In: Lund B, Baird-

Parker AC and Gould GW (eds) The Microbiological

Quality and Safety of Food, pp. 420–444. Gaithersburg,

MD: Aspen.

Lu

¨

cke FK (2000b) Utilization of microbes to process and to

preserve meats. Meat Science 56: 105–115.

Ordo

´

n

˜

ez JA, Hierro EM, Bruna JM and de la Hoz L (1999)

Changes in the components of dry-fermented sausages

during ripening. Critical Reviews in Food Science and

Nutrition 39: 329–367.

Prochaska JF, Ricke SC and Keeton JT (1998) Meat fermen-

tation – research opportunities. Food Technology 52(9):

52–57.

Varnam AH and Sutherland JP (1995) Meat and Meat

Products. London: Chapman & Hall.

Fermentations of the Far East

W R Stanton, Stanbury, Keighley, UK

J D Owens, The University of Reading, Reading, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001 The origin of oriental food fermentations is lost in

antiquity, although there is indirect evidence that the

earliest ‘cultivated plants’ were microorganisms, fer-

mentation being part of the hunter–gatherer practices

preceding agriculture. As mentioned later, ideas of

what is wild and what is cultivated have changed rad-

ically in recent years; most so-called virgin tropical

forest is in fact carefully managed by the local people,

who have taken advantage of their ‘human’ skills to

extract and detoxify products, whilst leaving them in

the wild, biochemically protected against the biota. No

precise archeological timing can be assigned, because

the techniques adopted by humans were acquired by

observation of the behavior of other animals. How-

ever, in order to understand these Far Eastern foods, it

may be helpful to visualize them as occupying two

main groups, a Chinese heartland and migrant-spread

group and an indigenous products group.

Chinese Heartland and Migrant-Spread Group:

Panoriental Fermented Foods

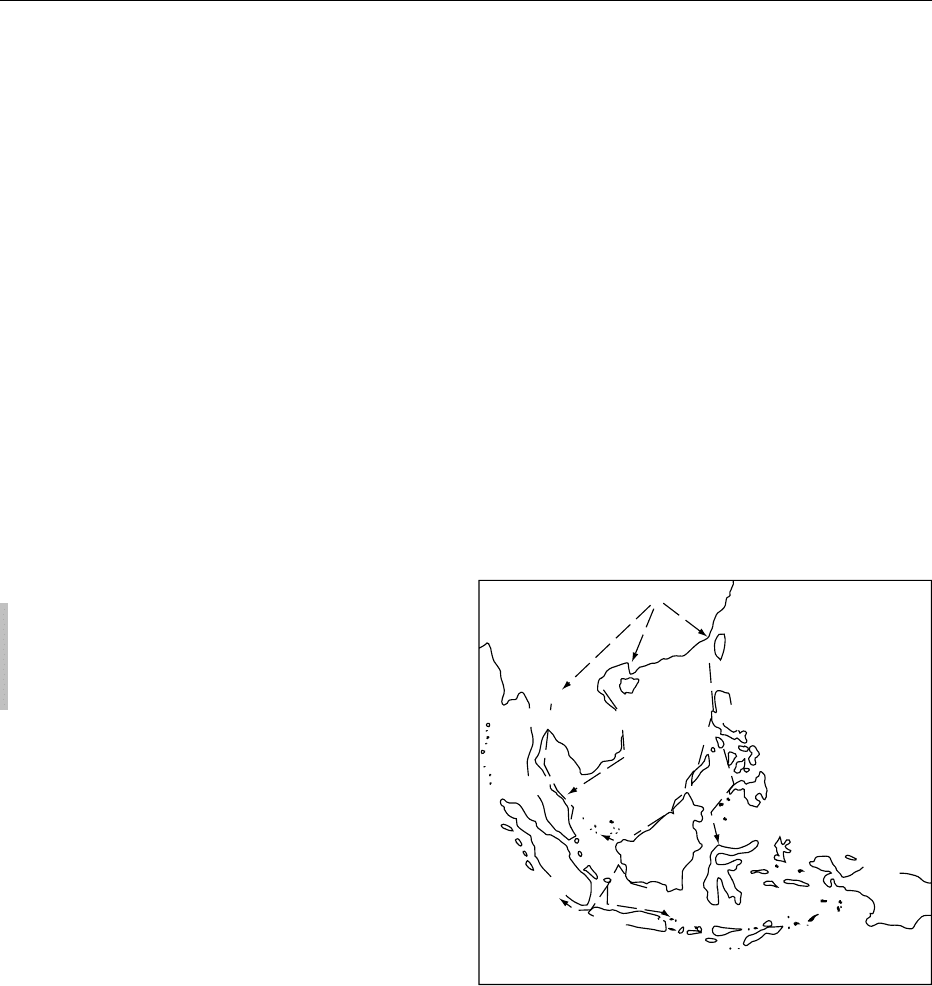

0002 The Chinese heartland and migrant-spread group con-

sists of those foods that are identifiable as originating

in China and, to a lesser extent, the Indian subcontin-

ent. They are encountered in the Far East, following

the spread – over the last 2000–3000 years – of mi-

grants from these two founts of culture, mainly south-

and eastwards from the temperate and monsoonal

regions in which they putatively originated (Figure 1).

0003Because these foods became, through the process of

transfer, out of context, as far as both climate and

substrate were concerned, they underwent subtle

changes:

.

0004in the organisms which took part in the fermenta-

tions;

.

0005in the duration of the fermentations;

.

0006in the utensils, materials, and conditions for oper-

ating the processes.

0007For example, the Mucorales such as Rhizopus,

liking warm humid conditions, replaced Aspergillus

and Penicillium. Bamboo, the banana leaf, and the

coconut shell replaced pottery.

China

Philippines

Vietnam

Malaya

Sumatra

Java

6

5

4

Papua

New

Guinea

Borneo

3

2

2

7

1

Thailand

fig0001Figure 1 Human migration and the spread of food fermentation

techniques in the Far East. 1, Postulated center of origin, 3000–

4000 years ago; 2, Land routes within the empire to the ‘vassal’

kingdoms of Indochina; 3, Sea routes and migratory routes hug-

ging coasts of the South China Sea, or traversing open sea by

island hopping; 4, An ancient porterage route across South

Malaya; 5, Small victualling and trading ports along the North-

west coast of Borneo; artefacts from this area show strong con-

nections with Chinese trade; 6, Java: a territory rich in traditions

of fermented foods; the raw materials, techniques and nomen-

clature provide evidence for the ‘Chinese origin’ hypothesis; 7, In

addition to the coastal trade, there is a strong tradition of over-

land migration into Thailand as well as in-situ development of

richly endowed indigenous cultures, such as the Khmer. After

Stanton WR (1985) Food fermentation in the tropics. In: Wood BJB

(ed.) Microbiology of Fermented Foods, pp. 193–211. London: Else-

vier, with permission.

2344 FERMENTED FOODS/Fermentations of the Far East

0008 Nevertheless, the links of the tropical foods with

their continental cultural roots may be seen in the

form of the ‘new’ foods and the processes used for

their manufacture, just as clearly as the links with the

cultural and linguistic traits of the Indian subcontin-

ent and China are themselves identifiable.

In-situ

(Tropical) Group: Indigenous Products

0009 Much earlier migration initiated the use of the great

diversity of plant and animal resources of the equa-

torial lands of Southeast Asia and their associated

freshwater and marine biotopes. This process took

place over, putatively, the last 30 000 years, i.e., over

the period of the spread of Meso- and Neolithic cul-

tures through the South and Southeast Asian regions.

The separation of the two groups of foods is incom-

plete, but this systematic approach is helpful in under-

standing the recipes and the current concern over the

loss of species diversity, through degradation of habi-

tats with the expansion of the human population, and

thus the potential loss of novel raw materials.

Role of Food Fermentation in the Humid Tropics

0010 The function of both groups in the diet has been, and

remains, to exploit otherwise toxic or inedible raw

materials, to preserve the harvest, to recover wastes

and generate attractive, stimulating, and accessory

foodstuffs, and to conduct these exercises with econ-

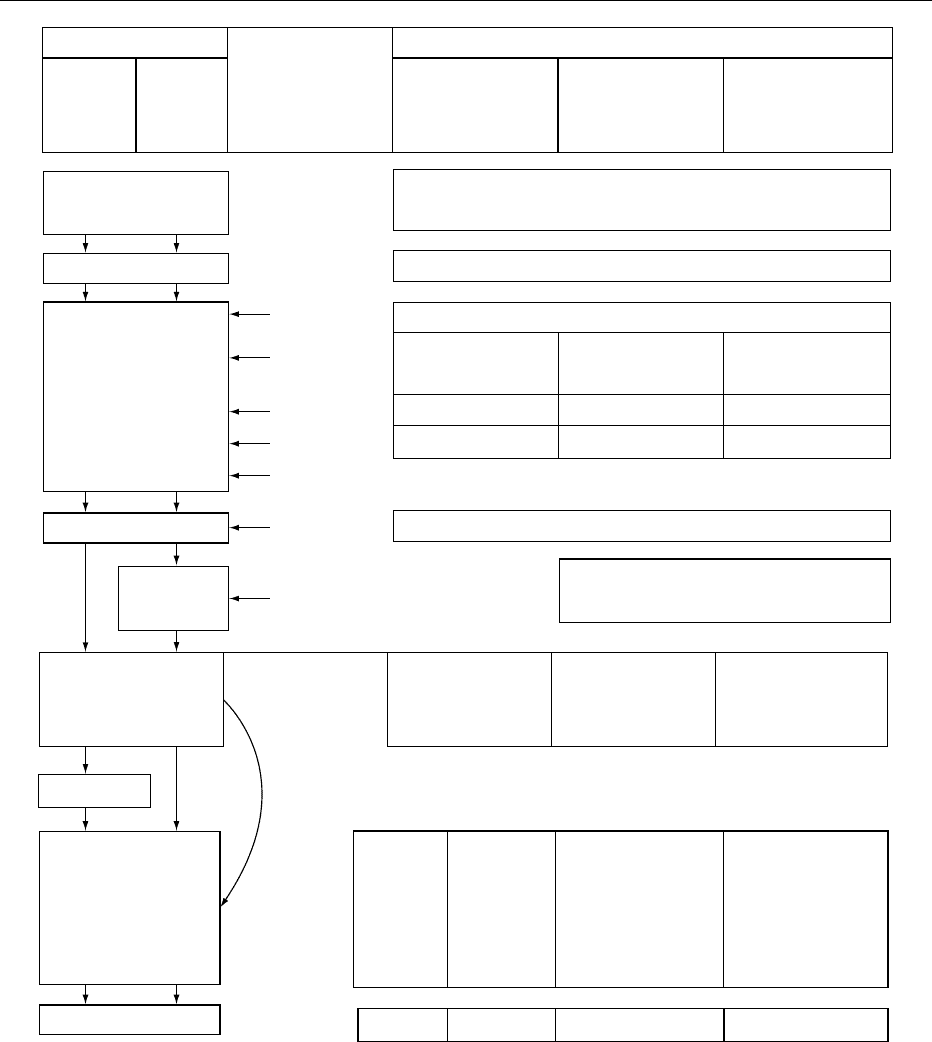

omy of expenditure and energy. Figure 2 shows

how fermentation fits the scheme of preservation

techniques.

Panoriental Fermented Foods

0011Typical of panoriental fermented products – now used

as foods worldwide – are those liquid relishes derived

from the soy bean, of which soy sauce is but one of

many ‘sho’, i.e., salt-assisted, processes. The soy bean

furnishes the type of substrate for transformation by

fermentation, embodying many of the characteristics

of a plant raw material requiring processing before it

is edible.

0012Soy sauce is the best known, but there are also solid-

state beanfermentations, the vegetable cheeses, such as

tempe, which have evolved to become ‘meat substi-

tutes.’ The role of these bean cheeses in diets is more

that of balancing, in a cereal diet, vitamin and essential

amino acid deficiency. It includes improving digesti-

bility (reducing bean flatulence) and eliminating anti-

nutritional factors, particularly antitryptic factors.

Natural products: Roots, Tubers, Stems, Leaves, Fruit, Seeds, Animals, Fish

Harvest

Food fermentation: Area of interest

Processing wastes

Solid: Peelings, press-cakes, milling waste

Liquid: Press-liquors, decortication wastes,

washing effluents, mother liquors

Fermentation by:

Lactic acid bacteria

Yeasts

Molds

Mixed populations

Conversion by microorganisms

Substrates

Conservation

Spoilage limitation by:

Drying

Freezing

Smoking

Chemicals

Sterilization by:

Cooking

Canning

Irradiation

Chemicals

Processing

Products

Compounds for food and

other industries

Supplements

Amino acids

Vitamins

Nucleotides

Flavoring compounds

Foods

Enriched

High protein

Nutritionally improved

Detoxified

Deterioration from microorganisms

Rotting

Molding

Putrefying

fig0002 Figure 2 Fermentation in relation to other processes used in the conversion of raw materials to foods. After Stanton WR (1969) Some

domesticated lower plants in Southeast Asian food technology. Adapted from Ucko PJ and Dimbleby GW (eds) The Domestication of

Plants and Animals, pp. 463–469. London: Duckworth.

FERMENTED FOODS/Fermentations of the Far East 2345

Tempe

0013 Tempe is a traditional Indonesian solid-substrate

fermentation in which soybeans are hydrated and

acidified, dehulled, cooked, and then fermented with

Rhizopus spp. The cotyledons become covered and

penetrated by a dense, white, nonsporulating myce-

lium, which binds them into a compact, sliceable

mass. Tempe is cooked by frying, steaming, or

boiling, and is consumed as a main ingredient of a

balanced meal with rice or starchy tubers and vege-

tables or as a snack food. It is estimated that 50% of

the 200 million Indonesians consume tempe daily as a

meat substitute. The high protein content and pleas-

ant, relatively bland taste has led to it occupying a

small, but expanding part of the vegetarian market in

Japan, the USA, and Europe.

0014 Manufacture Unlike soy sauce manufacture, the fer-

mentation of tempe is a short-duration process. The

small-scale manufacture of tempe is carried out as

follows:

1.

0015 Wash soy beans.

2.

0016 Soak for 24 h at tropical ambient temperature

(30+5

C), during which time a natural lactic

acid fermentation occurs, lowering the pH of the

beans to 4.5–5.3.

3.

0017 Dehull by treading or by machine.

4.

0018 Wash and float off hulls.

5.

0019 Cook the cotyledons by boiling or steaming for

0.5–2h.

6.

0020 Drain well and cool to below 35

C.

7.

0021 Inoculate with Rhizopus spp.

8.

0022 Pack into perforated polythene bags or wrap in

banana leaves.

9.

0023Ferment at ambient temperature (30+5

C) for

about 24 h to yield tempe.

0024Acidification is important to avoid misfermenta-

tion and invasion of undesirable bacteria. Perforated

plastic, normally polythene, was first used by Hessel-

tine – a pioneer of the study of the industrialization of

oriental fermented foods – in the late 1960s; it is

possibly one of the most elegant examples (in its

simplicity and small-scale applicability) of advances

in solid-state fermentation technology during the

twentieth century. Although primarily a mold fer-

mentation, most commercial tempe also includes a

substantial bacterial population. There are sugges-

tions that the bacteria fulfill useful functions, such

as the production of vitamin B

12

, but their presence is

not necessary for the production of good tempe. The

composition of tempe is given in Table 1. The wide

range of values shown in Table 1 is attributable to a

diversity of factors, including variation in the quality

of the beans and the extent of the use of additives and

adulteration. However, under laboratory conditions,

the protein content should be near the upper limit of

the range of values shown, i.e., 50%, as loss of pro-

tein in preparation is generally below 2%. Apart from

binding the cotyledons into a firm cake, the main

changes in the beans effected by the fermentation are:

1.

0025A net loss of 7–10% in dry matter. Approximately

15–20% of the initial substrate is used by the

mold, yielding 50–100 g of dry biomass per

kilogram of dry tempe.

2.

0026Hydrolysis of a substantial proportion of the tri-

acylglycerides to free fatty acids and mono- and

diacylglycerides. In mature tempe, free fatty acids

comprise 15–30% of total crude lipid. Fatty acids

serve as a major source of carbon and energy for

the mold, and around 25% of the initial lipids

present in the cotyledons are utilized during the

fermentation.

3.

0027Hydrolysis of about 25% of the initial protein,

most of which remains in the tempe as free

amino acids. A small part is oxidized, with the

release of ammonia and increase in the pH of the

cooked cotyledons from the initial 4.5–5.3 to 6.5–

7.0 in mature tempe.

tbl0001Table 1 Composition of tempe

Nutrient Content (%, dry-weight basis)

Protein 40–50

Crude fat 15–30

Carbohydrate 15–30

Crude fiber 5–12

Ash 1.5–3.0

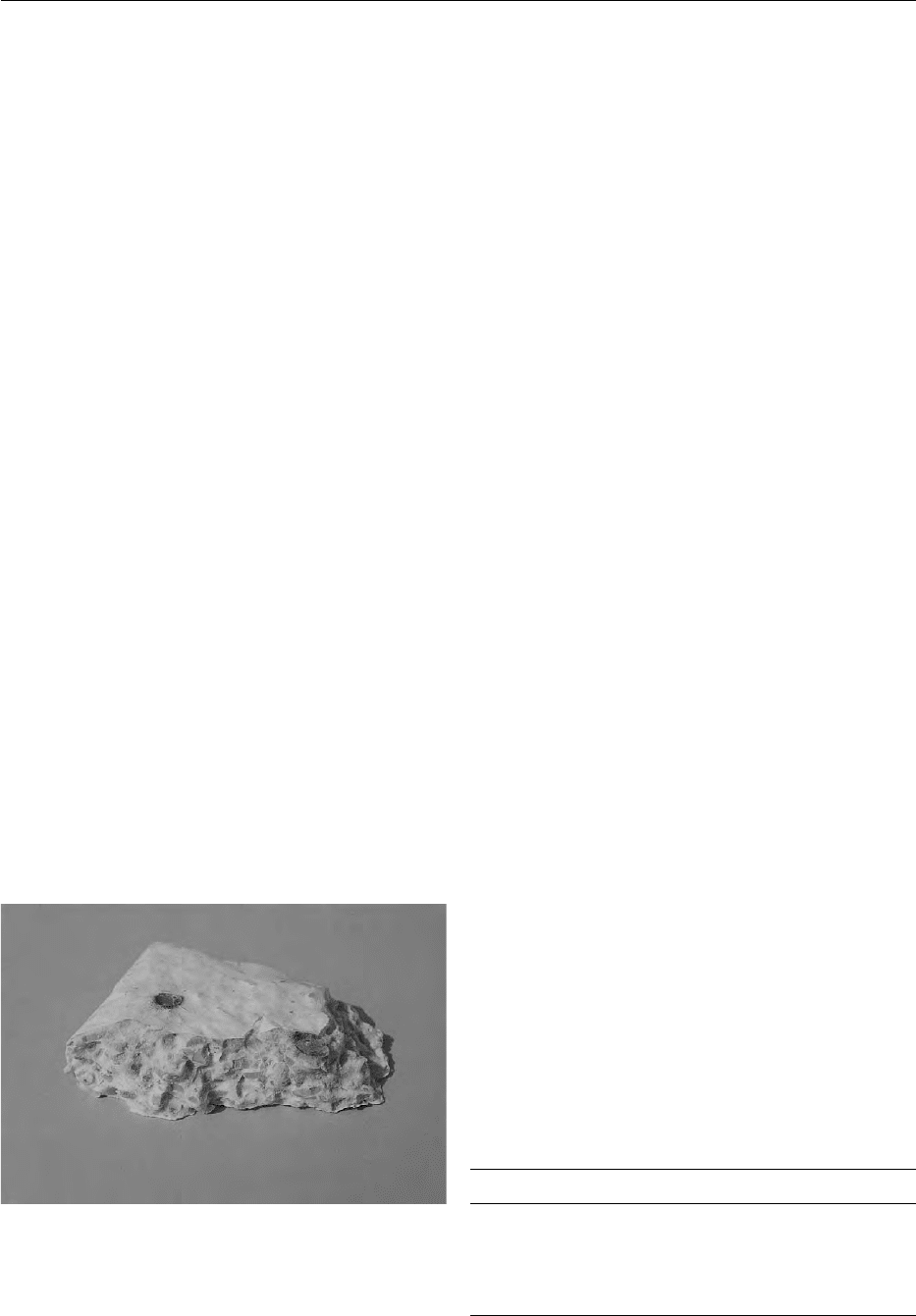

fig0003 Slide 1 (see color plate 52) Tempe. Growth of a fungus, Rhizo-

pus oligosporus, binds cooked, dehulled soybeans into a solid

cake. Tempe is a traditional Indonesian meat substitute that

also has a small part of the vegetarian market in Japan, the

USA, and Europe.

2346 FERMENTED FOODS/Fermentations of the Far East

4.0028 The mold does not use the soy bean oligosacchar-

ides, stachyose, raffinose, and sucrose, and the

concentrations of these change little during the

fermentation. However, a large proportion (70–

80%) of the oligosaccharides in the original

beans is lost by leaching during the hydration,

washing, and cooking of the cotyledons.

5.

0029 Isoflavone glycosides are largely hydrolyzed to the

aglycones, dadzein and genistein, which, it is sug-

gested, are more available than the isoflavones in

cooked soybeans. There is currently considerable

interest in possible health-promoting properties of

isoflavones.

Other Tempe-type Fermentations

0030 Many of the fermentations make use of waste

materials, such as oil extraction residues or other

food processing by-products.

0031 Common in western Indonesia is a product called

oncom (ontjom). It is made by a tempe-like fermenta-

tion, but the process differs in some respects:

1.

0032 Peanut (Arachis hypogaea) press cake is used in

place of the soy bean.

2.

0033 The preferred fungus is the orange–red-spored

Neurospora sitophila.

3.

0034 Sporulation of the fungus is encouraged, in con-

trast to tempe manufacture, where it is avoided.

0035 Oncom also may incorporate cassava press cake or

the residue from soy milk preparation, or it can be

prepared solely from soy milk residue. Coconut oil

extraction residue is another processing material that

can be fermented with Rhizopus spp., giving a product

called tempe bongkrek. However, this may be lethal,

if incorrectly prepared, because of the growth and

toxin production by Pseudomonas cocovenenans.

Natto and Related

Bacillus

-fermented Products

0036Natto is produced by an exclusively bacterial fermen-

tation of the soy bean using Bacillus subtilis.In

common with most other Japanese fermented foods,

it originated in China, where it is named shi. In con-

trast to the preparation of tempe, the hulls are left on

the steamed beans. In Japan, the manufacture is now

highly automated and uses carefully selected pure

starter cultures.

0037The cooked beans are inoculated with starter cul-

ture, packaged in small, usually polystyrene foam,

containers and fermented at a relatively high tem-

perature (40–42

C) for 12–16 h. The packages are

then cooled and held at 0–5

C for 1–2 days for

maturation. The result is a slime-coated product in

which the beans remain visible and separate. The

major biochemical change is the hydrolysis of protein

to peptides and amino acids. Natto is eaten with

boiled rice and is also used as a flavoring agent in

other dishes.

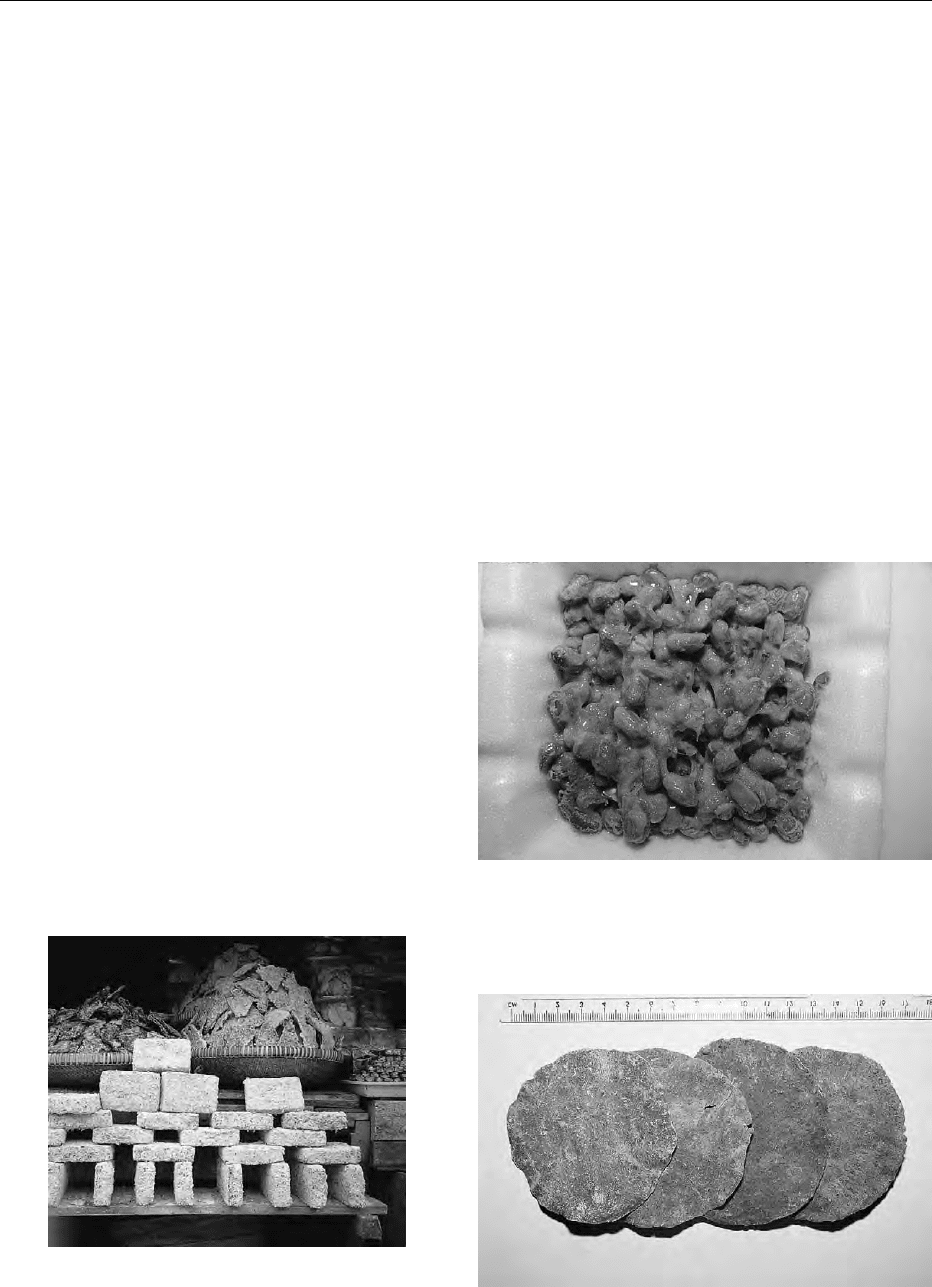

fig0004 Slide 2 (see color plate 53) Oncom (ontjom) in Bandung

market, Indonesia. Oncom is similar to tempe but uses peanut

press cake and the orange-spored fungus, Neurospora sitophila.

The material in the background is fried tempe.

fig0005Slide 3 (see color plate 54) Natto. A Japanese Bacillus proteo-

lytic fermentation of whole soybeans producing a characteristic-

ally slimy, strongly flavored product.

fig0006Slide 4 (see color plate 55) Thu-nuo, dried disks. A traditional

Thai Bacillus proteolytic fermentation of soybeans.

FERMENTED FOODS/Fermentations of the Far East 2347