Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

a-amylase or amyloglucosidase to some samples and

incubating them at 28–30

C for 48 h, it can be seen

whether any treatment clears the sample. If it works,

the problem is identified and an easy solution has

been found.

Use of Transglutaminase in Functional

Properties of Food

0075Transglutaminase (EC 2.3.2.13) catalyzes in vitro

cross-linking in whey proteins, soya proteins, wheat

proteins, beef myosin, casein and crude actomyosin

refined from mechanically deboned poultry meat. In

recent years, on the basis of the enzyme’s reaction to

gelatinize various food proteins through the forma-

tion of cross-links, this enzyme has been used in at-

tempts to improve the functional properties of food.

The modification of food proteins by transglutami-

nase may lead to textured products, help to protect

lysine in food proteins from various chemical reac-

tions, encapsulate lipids and/or lipid-soluble mater-

ials, form heat- and water-resistant films, avoid heat

treatment for gelation, improve elasticity and water-

holding capacity, modify solubility and functional

properties, and produce food proteins of higher

nutritional value through cross-linking of different

proteins containing complementary limiting essential

amino acids.

0076An overview of the application possibilities for

microbial transglutaminase in food processing is

given in Table 9. In meat and fish processing it is of

great interest to maximize the yield of marketable

products, particularly by restructuring low-value

cuts and trimmings to improve their appearance,

flavor, and texture. In vegetables and fruit transglu-

taminase is used to maintain freshness, by coating

them with a membrane containing transglutaminase

and proteins. Literature reports also cite a method

developed for reducing the allergenicity of some

food proteins and/or peptides: a

s1

-casein was treated

tbl0009 Table 9 Overview of application of microbial transglutaminase in food processing

Source Product Effect

Meat Hamburger, meatballs, stuffed dumplings Improved elasticity, texture, taste, and flavor

Canned meat Good texture and appearance

Frozen meat Improved texture and reduced cost

Molded meat Restructuring of meat

Fish Fish paste Improved texture and appearance

Krill Krill paste Improved texture

Collagens Shark-fin imitation Imitation of delicious food

Wheat Baked foods Improved texture and high volume

Soya bean Mapuo doufu Improved shelf-life

Fried tofu (aburaage) Improved texture

Tofu Improved shelf-life

Vegetables and fruits Celery Food preservation

Casein Mineral absorption promoters Improved mineral absorption in intestine

Gelatin Sweet foods Low-calorie foods with good texture, firmness, and elasticity

Fat, oil, and proteins Solid fats Pork-fat substitute with good taste, texture, and flavor

Plant proteins Protein powders Gel formation with good texture and taste

Seasonings Seasonings Improve taste and flavor

Partially reproduced from Zhu Y, Rinzern A, Tramper J and Bol J (1995) Microbial transglutaminase – a review of its production and application in food

processing. Applied Microbiology and Biotechnology 44: 277–282 with permission.

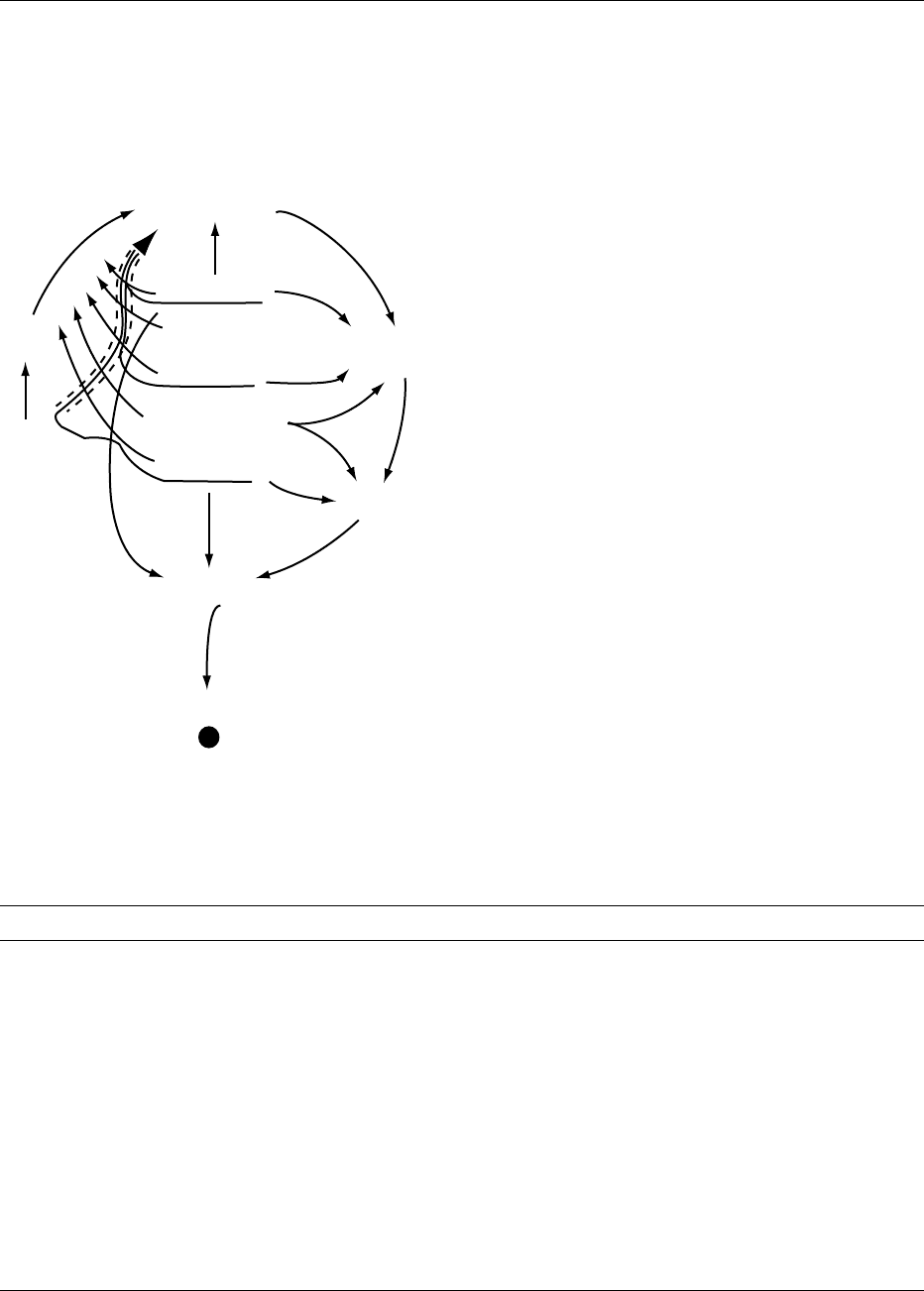

Brewing

Malt

Barley

Maize

Rice

β-Glucanase

Cellulase

Fermentation

α-Amylase

Glucoamylase

Peptidase

Aging

Filtration

Bottling

fig0006 Figure 6 Enzymes used in brewing. Data from Bigelis R (1993)

Carbohydrases. In: Nagodawithana T and Redd G (eds) Enzymes

in Food Processing, pp. 121–147. California: Academic Press.

ENZYMES/Uses in Food Processing 2137

with transglutaminase to manufacture cross-linked

casein, which was less allergenic.

0077 In developing countries, many people are still

suffering from starvation and efforts are being

focused on producing acceptable protein foods from

nonanimal protein, to solve the problem of protein

deficiency. On the other hand, in addition to their

awareness of health problems caused by obesity,

people in developed countries are increasingly aware

of the environmental burden caused by surplus live-

stock. When presented with a novel food product,

consumers are very sensitive to properties such as

flavor, nutritional value, appearance, shelf-life, and

palatability. In this respect, protein modification by

enzymes, especially by microbial transglutaminase,

the mass production of which can be achieved by

fermentation from cheap substrates, is one of the

most promising alternatives in developing novel

protein foods.

0078 Up to now, commercial transglutaminase has been

merely obtained from animal tissues. The compli-

cated separation and purification procedure results

in an extremely high price for the enzyme. The pro-

duction of transglutaminase derived from micro-

organisms was not reported until the late 1980s, and

recently a modified downstream process for purify-

ing microbial transglutaminase was described. The

microbial process no doubt has an advantage in its

independence from regional and climatic condition,

in addition to its reasonable cost. But it is still of great

interest to improve fermentation and downstream

processing to reduce production cost. Modification

of strains by genetic engineering is one of the alterna-

tives.

Cleaning

0079 A major use of enzymes as proteases has been in the

production of detergents. These are used widely in the

food industry, especially for cleaning-in-place appli-

cations, where the equipment is sensitive to heat. (See

Cleaning Procedures in the Factory: Types of Deter-

gent.)

0080 Pancreatin (extracted from the pancreatic glands

of animals), which contains the protein-degrading

enzyme trypsin, was used as early as 1913 in laundry

detergents. The detergent, being mainly composed of

ordinary washing soda (sodium carbonate), had an

excellent softening effect on water and helped to dis-

solve dirt. The trypsin, however, had only a limited

effect.

0081 During the 1960s, there was a significant new de-

velopment in the detergent industry when a mixture of

serine and microbial proteases, which appeared to be

less degradable by soaps, alkalis and temperature,

replaced trypsin. These enzymes have a serine-histi-

dine active site and produce their effect in the pH

range 6.5–10.0 and a temperature range of 30–60

C.

0082There was a temporary setback in the early 1970s

when it was realized that enzymes could cause allergic

reactions among the staff working in the enzyme

plant, in detergent factories, or the end users.

0083The introduction of encapsulated proteases in the

1980s and the withdrawal of the US Federal Trade

Commission’s restrictions were followed by a resur-

gence in the demand for proteases in detergents. Pro-

teases remove protein stains and deposits from a wide

range of food sources. These organic stains have a

tendency to adhere strongly to textile fibers and equip-

ment surfaces. The proteins act as glues, preventing

water-borne detergent systems from removing some

of the other components of the stain/deposit, such as

pigments and particulate material. Nonenzymatic de-

tergents are inefficient in removing proteins and can

result in permanent stains due to oxidation and de-

naturing caused by bleaching and drying.

0084Proteases hydrolyze proteins and break them down

into more soluble polypeptides. Through the com-

bined effect of surfactants and enzymes, stubborn

stains/deposits can be removed. Though protein

stains can be easily digested by enzymes, oil and

fatty stains have always been troublesome to remove.

The trend towards lower cleaning temperatures has

made the removal of grease spots an even greater

problem.

0085Amylases are also used to remove residues of

starchy foods, such as mashed potato, spaghetti, oat-

meal porridge, custard, gravy, and chocolate.

See also: Beers: Biochemistry of Fermentation; Biscuits,

Cookies, and Crackers: Methods of Manufacture; Bread:

Breadmaking Processes; Chemistry of Baking; Cakes:

Methods of Manufacture; Chemistry of Baking; Cheeses:

Starter Cultures Employed in Cheese-making; Mold-

ripened Cheeses: Stilton and Related Varieties; Surface

Mold-ripened Cheese Varieties; Enzymes: Functions and

Characteristics; Uses in Analysis; Fermented Milks:

Types of Fermented Milks; Other Relevant Products;

Wines: Production of Table Wines; Production of

Sparkling Wines

Further Reading

Alkorta I, Garbisu C, Liama MJ and Serra JL (1998) Indus-

trial applications of pectic enzymes: a review. Process

Biochemistry 33: 21–28.

Bigelis R (1993) Carbohydrases. In: Nagodawithana T and

Redd G (eds) Enzymes in Food Processing, pp. 121–147.

California: Academic Press.

Chitpinityol S and Crabbe MJ (1998) Chymosin and aspar-

tic proteinases. Food Chemistry 61: 395–418.

2138 ENZYMES/Uses in Food Processing

Cowan DA (1994) Industrial enzymes. In: Moses V and

Cape RE (eds) Biotechnology, pp. 311–340. UK: Har-

wood Academic Publisher.

Godfrey T and West SI (1996) Introduction to industrial

enzymology. In: Godfrey T and West SI (eds) Enzym-

ology, pp. 1–8. London: MacMillan Press.

Godtfredesen SE (1993) Lipases. In: Nagodawithana T and

Redd G (eds) Enzymes in Food Processing, pp. 205–214.

California: Academic Press.

Goll DE, Robson RM and Stromer MH (1977) Muscle

proteins. In: Whitaker JR and Tannenbaum SR (eds)

Food Proteins, pp. 121–174. Westport: AVI.

Guzman-Maldonado H and Paredes-Lopez O (1995) Amy-

lolytic enzymes and products derived from starch: a

review. Critical Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition

35: 373–403.

Lanzarini G and Pifferi PG (1990) Enzymes in fruit juice

industry. In: Cantarelli C and Lanzarini G (eds)

Biotechnology Applications in Beverage Production,

pp. 189–221. London: Elsevier.

Linko P (1987) Enzymes in the industrial utilization of

cereals. In: Kruger JE, Lineback D and Stauffer CE

(eds) Enzymes and their Role in Cereal Technology,

pp. 357–374. St Paul: AACC.

Mathewson PR (2000) Enzymatic activity during bread

baking. Cereal Foods World 45: 98–101.

O’Rourke T (1996) Brewing. In: Godfrey T and West SI

(eds) Enzymology, pp. 103–131. London: MacMillan

Press.

Schmid RD and Verger R (1998) Lipases: interfacial

enzymes with attractive applications. Angewandthe

Chemie International Edition (in English) 37: 1608–

1633.

Whitaker JR (1982) Enzymes of importance in high protein

foods. In: Dupuy P (ed.) Proceedings on the Use of

Enzymes in Food Technology, pp. 329–358. Paris:

Lavoisier.

Zhu Y, Rinzem A, Tramper J and Bol J (1995) Microbial

transglutaminase – a review of its production and appli-

cation in food processing. Applied Microbiology and

Biotechnology 44: 277–282.

Uses in Analysis

J R Whitaker, University of California, Davis, CA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Enzymes are ideal for analyses because of their high

specificity and sensitivity. Any compound that affects

the activity of an enzyme, i.e., substrate, inhibitor, or

activator, can be determined rapidly and quantita-

tively by adding such compounds to a controlled

enzyme reaction and comparing the results without

the compound (control). Also, measurements of ac-

tivities of selected enzymes in a biological specimen

under standard conditions are useful in medicine for

the diagnosis and prognosis of almost all diseases.

More recently they have been used for determining

specific genetically related diseases. They are also used

for assessing nutritional deficiencies, physical damage

to organs, suitability for and adequacy of processing

and quality of foods, identifying subcellular organ-

elles and membrane structures, and structural config-

urations of molecules. Enzymes are ideal reporters for

measuring antigens to specific antibodies (enzyme

immunoassays).

0002Enzyme usage in analyses is not new. Peroxidase

was used for hydrogen peroxide analysis as early as

1845. Enzymatic carbohydrate determination in bio-

logical materials was an accepted method by the end

of the nineteenth century. But most progress in using

enzymes analytically has occurred in the last 20 years

as a result of readily available pure enzymes, better

understanding of the factors which affect enzyme

activity, enzyme kits for specific determinations,

easily usable sensitive techniques, and instrumenta-

tion matching the specificity and sensitivity of the

enzymes. The rapid progress in sequencing genes,

including the human genome, is due to two specific

types of enzymes: the restriction endonucleases and

the polymerases.

Principles and Applications

0003Compounds to be measured must bind stereospecific-

ally at the active site of an enzyme or another specific

location on the enzyme such that the activity of the

enzyme is affected (eqn 1).

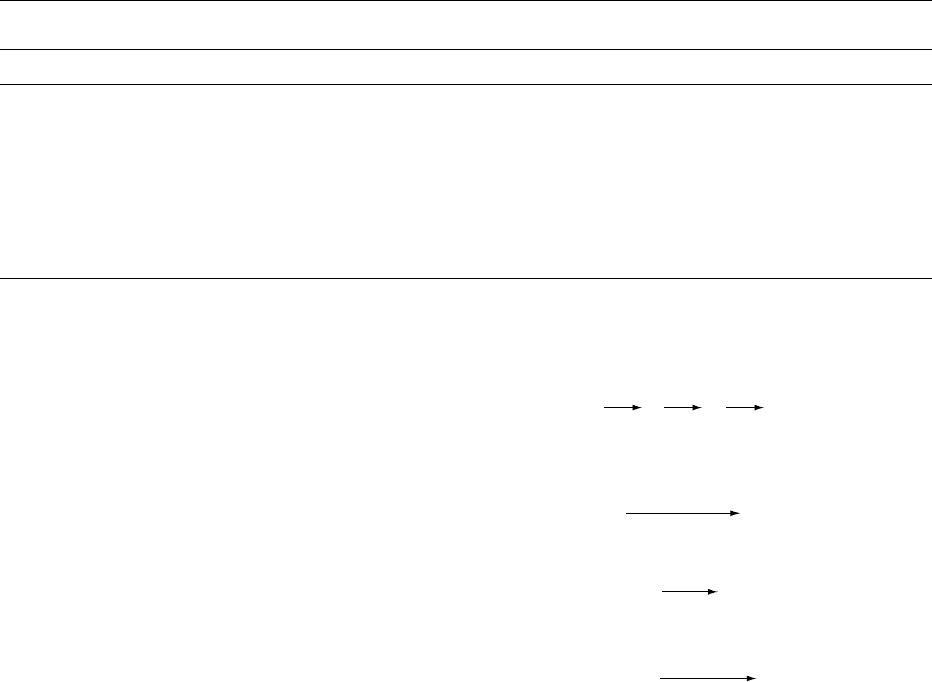

E + S E

.

S E

.

P E + P

E

.

X + S E

.

S

.

X E

.

P

.

X E

.

X + P

X

K

d

X

K

d

k'

1

k'

−1

k

1

k

−1

k'

3

k'

2

k'

−3

k'

−2

k

2

k

−2

k

3

k

−3

(1)

E, enzyme; S, substrate; ES, enzyme-substrate com-

plex; EP, enzyme-product complex; P, product; X,

inhibitor or activator; EX, enzyme-inhibitor (or acti-

vator) complex; ESX, enzyme-substrate-inhibitor (or

activator) complex; EPX, enzyme-product-inhibitor

(or activator) complex; K

d

, dissociation constant; k

1

,

k

2

, k

3

, k

0

1

, k

0

2

and k

0

3

are forward rate constants.

0004There must be a predictable relationship between the

concentration of a compound and its effect on enzym-

atic activity. Standard curves for compounds and

ENZYMES/Uses in Analysis 2139

their products, including enzymes, to be determined

are required in order to obtain absolute concentra-

tions. In preparing the standard curve of initial vel-

ocity, v

o

, versus compound or product concentration,

purity of the analyte is essential and exact reproduc-

tion of experimental conditions is required. In the

total change method (below), strict adherence to ex-

perimental conditions (such as rate of reaction) is not

required, but it is essential to have pure standard

compounds and products and to insure the reaction

has gone to completion.

Determination of Substrate

Concentration

000 5 The concentration of any compound that serves as a

substrate, S, for an enzyme can be determined quan-

titatively by its effect on the initial velocity, v

o

, of the

reaction, provided K

m

and V

max

are known, as shown

in eqn 2, and provided [S]

o

<20K

m

:

v

o

¼ V

max

½S

o

=ðK

m

þ½S

o

Þð2Þ

Best results are obtained at [S]

o

<5K

m

. This is called

the rate (or kinetic) assay method.

0006 The concentration of a compound that is a sub-

strate can also be determined by a total change

method when all the substrate is converted to prod-

uct, which is then measured. It is essential to insure

that all substrate has been converted to product,

which may take several hours at the concentration

of enzyme used in rate assays. Therefore, higher

concentrations of enzymes are used in total change

method assays than in rate assays. The total

change method cannot be used for reactions that

reach an equilibrium between substrate and product

unless the product is trapped, forcing the reaction to

completion. An example is alcohol dehydrogenase

(alcohol:NAD

þ

oxidoreductase, EC 1.1.1.1) acting

on ethanol and NAD

þ

, as shown in eqn 3. Hydro-

xylamine is used to trap ethanal as the oxime, forcing

the reaction to completion (eqn 4). The NADH con-

centration is measured spectrophotometrically.

CH

3

CH

2

OH þ NAD

þ

Ð CH

3

CHO þ NADH þ H

þ

ð3Þ

CH

3

CHO þ NH

2

OH Ð CH

3

CHNOH þ H

2

O ð4Þ

0007Special care must be taken in determining concentra-

tions of substrates which exist in more than one

anomeric form, in equilibrium with each other. An

example is the mutarotation of reducing sugars. Glu-

cose at equilibrium exists in the a, b, and open-chain

forms in the ratio of 33:66:1, respectively. Glucose

oxidase, often used to determine glucose concentra-

tions, has strong preference for the b-d-glucose

anomer, versus the a-d-glucose anomer (156:1 rela-

tive rate of oxidation). Therefore, both the total

change method and the rate assay method may not

give the correct concentration, unless a standard

curve for glucose is established under the exact same

conditions.

0008Some examples of compounds that can be quanti-

tatively determined because they are enzyme sub-

strates are shown in Table 1. Only a very few

examples are given, since, with more than 1000

enzymes with individual specificities, at least that

number of compounds can be uniquely determined.

(See Fructose; Lactose; Starch: Structure, Properties,

and Determination.)

0009Advantages of enzyme analyses for substrates,

versus other types, include: (1) the very high specifi-

city, permitting isomers to be distinguished; (2) no

need for partial purification; and (3) the ability to

work at room temperature, or below, with thermo-

labile compounds. An example will illustrate this.

Reducing sugar methods, such as alkaline copper

solutions, ferricyanide or 3,5-dinitrosalicylic acid

for glucose, will determine all reducing sugars in

the solution, plus other reducing compounds. How-

ever, glucose oxidase, which catalyzes the reaction

tbl0001 Table 1 Analytical determination of compounds that are substrates

a

Compound Enzymeused Analysismethod

Ammonia Glutamate dehydrogenase S; NADH ! NAD

þ

Ethanol Alcohol dehydrogenase S; NAD

þ

! NADH

D-Fructose Hexokinase S; NADP

þ

! NADPH, in coupled assay

D-Glucose Glucose oxidase S; H

2

O

2

with peroxidase

L-Lactic acid L-Lactate dehydrogenase S; NAD

þ

! NADH

D-Lactic acid D-Lactate dehydrogenase S; NAD

þ

! NADH

Lactose b-Galactosidase S; H

2

O

2

with peroxidase and glucose oxidase

Starch Amyloglucosidase S; NADH ! NAD

þ

, in coupled assay through glucose and glucose oxidase

Urea Urease E; NH

3

electrode

a

S, spectrophotometric method; E, electrometric method.

Adapted from Guilbault GG (1984) Analytical Uses of Immobilized Enzymes. New York: Marcel Dekker.

2140 ENZYMES/Uses in Analysis

shown in eqn 5, will only determine glucose. Fur-

thermore, it is absolutely specific for d-glucose

versus l-glucose and oxidizes b-d-glucose 156

times more rapidly than a-d-glucose. The reaction

shown in eqn 6 is not catalyzed by glucose oxidase.

The rate is slower than that of eqn 5 and therefore

cannot be used to determine glucose concentration

by the rate method. Therefore, the H

2

O

2

concen-

tration is determined by use of peroxidase and a

chromagen that gives a colored compound that is

measured spectrophotometrically (coupled reac-

tions). The peroxidase and chromagen concentra-

tions must be high enough so that the rate of

reaction shown in eqn 5 is rate-determining, not

the reaction shown in eqn 7.

β-D-Glucose + O

2

β-D-Glucone-δ-lactone

Glucose

oxidase

(5)

+ H

2

O

2

β-D-Glucone-δ-lactone + H

2

O

β-

D-Gluconic acid

(6)

H

2

O

2

+ Chromagen

peroxidase

Colored compound

(7)

Determination of Inhibitor Concentration

0010 Any compound that decreases v

o

when added to an

enzyme–substrate system is an inhibitor. Compounds

that are reversible inhibitors can only be determined

by rate assay methods, while irreversible inhibitors

can be determined by either rate assays or total

change assays. When X in eqn 1 binds only to E,so

as to decrease enzyme activity (i.e., both ES and EX

are formed), it is a competitive inhibitor; k

0

1

is zero.

Therefore, the concentration of the compound can be

determined from the ratio of v

0

o

/v

o

, where v

0

o

is the

initial velocity determined in the presence of a fixed

concentration of inhibitor, [I], and v

o

is the initial

velocity determined in the absence of inhibitor pro-

vided K

m

,[S], and K

i

( ¼ [E][I]

o

/[EI]; K

d

in eqn 1)

for the inhibitor are known. This relationship is

shown as:

v

0

o

=v

o

¼ðK

m

þ½S

o

Þ=fð1 þ½I

o

=K

i

Þ=K

m

þ½S

o

gð8 Þ

0011 If X binds to E and E S equally well (eqn 1) and k

0

1

and k

0

2

are zero, the X is a linear noncompetitive

inhibitor. [I]

o

can be determined from:

v

0

o

=v

o

¼ 1 þ½I

o

=K

i

ð9 Þ

provided K

i

for the inhibitor is known.

0012If X binds only to ES (eqn 1) and k

0

2

is zero, then

X is a linear uncompetitive inhibitor. [I]

o

can be

determined from:

v

0

o

=v

o

¼ðK

m

þ½S

o

Þ=fK

m

þ½S

o

ð1 þ½I

o

=K

i

Þg ð10Þ

provided K

m

,[S]

o

, and K

i

are known.

0013If X reacts chemically with E to form an irrevers-

ible product, E-X, then the extent of inhibition is

linearly related to the concentration of X as long as

[X]<[E] and the reaction is allowed to go to comple-

tion (total change method). The concentration of X

can be calculated, provided [E]

o

is known by:

v

0

o

=v

o

¼ð½E

o

½E-XÞ=½E

o

ð11Þ

where [E-X] ¼ [X]and[E]

o

is concentration of total

active enzyme used. Table 2 gives a few examples of

compounds that can be determined enzymatically be-

cause they are enzyme inhibitors, thereby decreasing

v

o

when added to an enzyme–substrate system.

0014Theoretically, any compound that is a substrate can

be determined by inhibition kinetics since two sub-

strates (one at a fixed concentration, while the un-

known substrate concentration is variable) in the

system compete for binding at the active site of

the enzyme, based on their relative K

m

values. One

need only determine v

o

for one of the substrates (con-

trol), and treat the second substrate as a competitive

inhibitor to determine v

0

o

.(See Aluminum (Alumin-

ium): Properties and Determination; Ascorbic Acid:

Properties and Determination; Lead: Properties and

Determination; Mercury: Properties and Determin-

ation.)

Determination of Activator Concentration

0015Any compound that increases v

o

when added to an

enzyme-substrate system is an activator. Compounds

tbl0002Table 2 Analytical determination of compounds that are

inhibitors

a

Compound Enzymeused Analysismethod

Pesticides Cholinesterase E; H

þ

; thiocholine

DDT Carbonic anhydrase S; H

þ

with indicator

Heparin Ribonuclease S; degradation of RNA

Ascorbic acid Catalase S; uric acid

Ag

þ

Alcohol dehydrogenase

(yeast)

S; NAD

þ

! NADH

Al

3 þ

Alkaline phosphatase S; p-nitrophenol

Hg

2 þ

Alcohol dehydrogenase S; NAD

þ

! NADH

Pb

2 þ

Peroxidase F; fluorescent product

F

Liver esterase E; H

þ

S

2

Peroxidase F; fluorescent product

a

The methods listed for the anions may not be absolutely specific: similar

types of ions may interfere.

DDT, dichlorodiphenyltrichloroethane; E, electrometric method; F,

fluorescent method; S, spectrophotometric method.

Adapted from Guilbault GG (1984) Analytical Uses of Immobilized Enzymes.

New York: Marcel Dekker.

ENZYMES/Uses in Analysis 2141

that form a rapid equilibrium complex with an

enzyme (and/or ES) as shown in eqn 1 can only be

determined by rate assay methods. This is character-

ictic of coenzymes, such as NAD

þ

, NAD(P)

þ

, nucle-

otide triphosphate coenzymes adenosine triphosphate

(ATP), uridine 5

0

-triphosphate, cytidine 5

0

-triphos-

phate) and some metal ions. At a fixed concentration

of enzyme and substrate, the concentration of activa-

tor, A, can be determined from:

v

o

o

¼ v

2

o

v

o

¼ V

max

½A=ðK

d

þ½A Þð12Þ

providedK

d

(¼[E][A]/[E A])andV

max

areknown.v

2

o

is

initial velocity in the presence of the activator. In most

cases,v

o

intheabsenceofcoenzymeiszero,sothatv

0

o

¼

v

2

o

isobserved;thisistheincreaseinactivityinpresence

of a given concentration of A.(See Coenzymes.)

0016 Activators that form tight complexes (K

d

<10

9

mol l

1

) with enzyme, such as prosthetic groups and

some metal ions, increase activity of the enzyme in a

linear fashion (v

o

o

is directly proportional to [A]

o

).

Therefore, only a total change method is useful.

0017 It is essential to prepare a standard curve of v

o

versus [A]

o

in order to convert measured v

o

values

to absolute concentration. Purity of the standard

activator and reproduction of experimental condi-

tions are essential.

0018 Table 3 gives a few examples of compounds that

activate enzymes. Several inferences may be drawn

from the examples presented. With the exception of

O

2

, all the compounds listed are cofactors. They are

absolutely required for enzymatic activity.

0019 One enzyme may be used to analyze for several

compounds. For example, luciferase can determine

luciferin (substrate), ATP, Mg

þ

,andO

2

concentra-

tions, since all affect the activity of the enzyme

(eqn 13).

Luciferin+O

2

Luciferase

Oxidized luciferin

ATP, Mg

2+

(+ phosphorescence)

(13)

Determination of Enzyme Concentration

0020Determining enzyme concentration by measuring the

initial velocity, v

o

, at which a substrate is converted to

product seems straightforward. Yet it is fraught with

difficulties unless careful attention is given to the

design of the experiment, as time, substrate, pH,

temperature, activators, and inhibitors all affect v

o

for a fixed concentration of enzyme. Therefore, if the

enzyme concentration, [E]

o

, is to be measured accur-

ately and precisely, all these other parameters must

be controlled exactly among experiments. It is im-

portant to determine the initial velocity, v

o

, so that

changes in substrate concentration, stability of the

enzyme, approach to equilibrium, and/or inhibition

by the product are not factors. The substrate concen-

tration does not need to be much greater than K

m

when v

o

is measured. Any substrate concentration,

when precisely reproduced, will give a linear rela-

tionship between v

o

and [E]

o

, with a few exceptions.

The temperature should be below optimum tempera-

ture so the enzyme is stable and the pH must be close

to the optimum pH for maximum sensitivity.

0021Determination of absolute concentration of

enzyme based on v

o

requires a standard preparation

of the enzyme with known purity, based on activity.

For example, if it is known that a 5 ml aliquot con-

taining 1 mg of 100% active pure enzyme has a v

o

of

30 mmol of product formed per minute, while a 5 ml

aliquot of an unknown sample has a v

o

of 6 mmol of

product formed per minute under the same condi-

tions, then the unknown aliquot contains 0.2 mgof

the enzyme.

0022Table 4 gives a few selected examples of analytical

determinations of enzyme concentration. (See Spec-

troscopy: Fluorescence; Overview.)

Structural Analysis

0023Because of their high specificity, enzymes are ideal

probes of molecular structure. They can distinguish

between: d/l, cis/trans, a/b, and other stereospecific

configurations; nature, location, and sequence of

monomeric units in heteropolymers (proteins, carbo-

hydrates, nucleic acids); and secondary, tertiary, and

quaternary structures of polymers. They are useful in

determining location of enzymes and substrates in

organs (histochemistry) and in identifying subcellu-

lar organelles (based on enzyme composition), cell

walls and membranes. The restriction enzymes

and ligases are essential tools in recombinant DNA

tbl0003 Table 3 Analytical determination of compounds that are

activators

a

Compound Enzyme used Analysismethod

ATP Luciferase S; NADH ! NAD

þ

,in

coupled reaction

FAD

D-Amino acid oxidase E; O

2

electrode

K

þ

Phosphofructokinase S; activation of enzyme

Mg

2 þ

Luciferase F; chemiluminescence

Zn

2 þ

Aminopeptidase

apoenzyme

S; p-nitrophenol

O

2

Luciferase F; chemiluminescence

a

A few examples of many. There are alternative methods, depending on

instruments, substrates, and enzymes available.

ATP, adenosine triphosphate; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; E,

electrometric method; F, fluorescent method; S, spectrophotometric

method.

Adapted from Guilbault GG (1984) Analytical Uses of Immobilized Enzymes.

New York: Marcel Dekker.

2142 ENZYMES/Uses in Analysis

technology and genetic engineering, being highly

specific for nucleotide primary and secondary struc-

tures. As probes of structure, unequivocal deter-

mination of activity, or lack of activity, is more

important than the absolute velocity of product for-

mation (v

o

).

Determination of

v

o

0024 Determination of v

o

for formation of product (dP/dt),

disappearance of substrate ( dS/dt), change in energy

(as heat), or change in pH is required for analytical

use of enzymes, as indicated by the preceding discus-

sion. This requires the ability to detect a change

during the reaction. Changes in absorbance, fluores-

cence, phosphorescence, electrical properties includ-

ing pH, or heat are appropriate monitors. Excellent

instrumentation is available for detection of all these

changes. The best methods are those where a continu-

ous recording of the change is possible, often with

software to convert the measured rate of change dir-

ectly to concentration of the compound being meas-

ured. Data accumulation and analysis are easy when

the change is continuously recorded. However, some-

times an aliquot of the reaction must be removed

periodically, another reagent added to give a colored

derivative (for example) of product or substrate and

then the concentration of the derivative determined.

Sometimes v

o

can be measured only after chromato-

graphic separation of the products. These are lengthy,

laborious assays that frequently lead to one-point

assays. v

o

, based on one-point assays, must be

accepted with great caution.

002 5 Often, solutions to difficult analyses are possible

via coupled enzyme assays. A coupled enzyme assay

involves two or more enzymes, in which the product

of the last enzyme is measured as shown in eqn 14.

The intent is to measure the concentration of A

(or E

1

). However, the product B is analytically very

difficult to determine, while D is very easy to

determine:

(14)

A

BCD

E

1

E

2

E

3

0026A specific example will illustrate this better (eqns

15–17).

(15)

Sucrose + H

2

O

Invertase

Glucose + Fructose

Glucose + O

2

+ H

2

O

Glucose

D-Gluconic acid + H

2

O

2

Oxidase

(16)

H

2

O

2

+ Chromagenic

substrate

Peroxidase

Fluorescent product

(or colored)

(17)

0027Coupled reactions often involve terminal enzymes

requiring NAD

þ

(NADH) or NADP

þ

(NADPH),

since the extinction coefficient at 340 nm is 6.22

10

3

mol l

1

cm

1

for NADH (or NADPH) versus

NAD

þ

(or NADP

þ

), a very large change.

0028Coupled reactions require enzymes with similar pH

optima and that v

o

( ¼ k

2

[E][S]

o

/(K

m

þ [S]

o

)) be at

least 100 times larger for reactions catalyzed by E

2

,

E

3

, etc., than for E

1

. This is usually met by using high

concentrations of E

2

, E

3

, etc. The rationale for this is

the concentrations of final product measured (D in

eqn 14; hydrogen peroxide in sucrose determination

eqns 15–17) must be a stoichiometric reflection of

concentration of substrate A (or E

1

) being deter-

mined. The examples in Tables 1–4 illustrate how

frequently coupled reactions are used.

0029Soluble enzyme systems are not required for deter-

mining v

o

(and analyte concentration). In fact,

present emphasis is on the use of immobilized enzyme

systems in columns, electrodes, biosensor chips

and antibody–enzyme conjugates (enzyme-linked

immunosorbent assay (ELISA), for example).

Immobilized enzymes are more stable than nonim-

mobilized enzymes and may be used repeatedly.

Dozens of enzyme electrodes are available (several

tbl0004 Table 4 Analytical determination of enzyme concentration

a

Enzyme Substrate used Analysismethod

Catalase H

2

O

2

E; O

2

b-Galactosidase o-Nitrophenyl-b-D-galactoside S; o-nitrophenol

Invertase Sucrose S; use of glucose oxidase/peroxidase coupled assay

Lipase Tributyrin E; H

þ

Pectin methylesterase Pectin E; titrate H

þ

formed

Peroxidase H

2

O

2

, 4-aminoantipyrine, p-hydroxybenzoate S; oxidized, conjugated 4-aminoantipyrine

Phosphatase, alkaline p-Nitrophenyl phosphate S; p-nitrophenol

Polyphenol oxidase Pyrocatechol S; benzoquinone

Xanthine oxidase Hypoxanthine S; uric acid

a

There are several methods available for each enzyme. Availability of instruments and substrates often determine choice of method.

E, electrometric method; F, fluorescent method; S, spectrophotometric method.

Adapted from Guilbault GG (1984) Analytical Uses of Immobilized Enzymes. New York: Marcel Dekker.

ENZYMES/Uses in Analysis 2143

commercially) that have response times equivalent to

a hydrogen (pH) electrode and can be used repeatedly

for several months. Biosensors involving multiple

microchips are being developed, which may deter-

mine up to eight or more enzymes, substrates, or

other compounds simultaneously when a drop of

blood, urine, or other biological fluid is added. (See

Immunoassays: Radioimmunoassay and Enzyme Im-

munoassay.)

See also: Aluminum (Aluminium): Properties and

Determination; Ascorbic Acid: Properties and

Determination; Coenzymes; Fructose; Immunoassays:

Radioimmunoassay and Enzyme Immunoassay; Lactose;

Lead: Properties and Determination; Mercury: Properties

and Determination; Spectroscopy: Overview; Starch:

Structure, Properties, and Determination

Further Reading

Bergmeyer HU, Bergmeyer J and Grassl M (eds) (1983)

Methods of Enzymatic Analysis, 3rd edn. Weinheim:

Verlag Chemie.

Colowick SP and Kaplan NO (eds) (1955–1999) Methods

in Enzymology, vols 1–300. Orlando: Academic Press.

Guilbault GG (1984) Analytical Uses of Immobilized

Enzymes. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Whitaker JR (1974) Analytical applications of enzymes. In:

Whitaker JR (ed.) Food Related Enzymes. Advances in

Chemistry Series 136: 31–78.

Whitaker JR (1984) Biological and biochemical assays in

food analysis. In: Stewart KK and Whitaker JR (eds)

Modern Methods of Food Analysis, pp. 187–225. West-

port: AVI.

Whitaker JR (1985) Analytical uses of enzymes. In: Gruen-

wedel DW and Whitaker JR (eds) Biological Techniques.

Food Analysis: Principles and Techniques, vol. 3, pp.

297–377. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Whitaker JR (1994) Principles of Enzymology for the Food

Sciences, 2nd edn. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Whitaker JR (1996) Enzymes. In: Fennema OR (ed.) Food

Chemistry, 3rd edn, pp. 514–518. New York: Marcel

Dekker.

EPIDEMIOLOGY

P C Elwood, Llandough Hospital, Penarth, South

Glamorgan, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Aims of Epidemiology

0001 Epidemiology is the study of health and disease in the

community. There are two groups of aims: first, to

describe the distribution, the pattern, and the natural

history of disease in the general population, and

second, to identify factors that may be causal in a

disease process, and to evaluate strategies for the

control, management, and prevention of a disease.

0002 In nutritional research, epidemiology aims to iden-

tify associations between nutrients or food items and

the risk of a disease, and then test these associations

to verify whether they are likely to be causal. In

practice, epidemiology is multifaceted and a number

of preliminary considerations will help to put it

into context within general medical and biological

research.

0003 Epidemiologists rarely generate hypotheses. Most

ideas about the causation of disease arise from clinical

observations, metabolic studies, or other intensive

investigations. The role of the epidemiologist is to

take these ideas and test them in representative

samples of the general community or, if appropriate,

in representative series of patients. In doing this the

epidemiologist not only tests the relevance of a factor

to the disease, but also seeks to obtain an estimate of

the relative importance of the mechanism or factor.

Furthermore, in a well-designed comprehensive

study, the extent to which the effect of any particular

factor of interest is independent of the effects of other

factors is established. This generally requires large

complex and long-term studies, based on samples of

subjects that truly represent the population.

0004The interest of the epidemiologist is therefore on

communities and his or her attention focuses ultim-

ately on lifestyles, on nutrition, and on environmental

factors. Thus the recent finding that certain throm-

bosis-related factors, such as plasma fibrinogen, are

very strongly predictive of future ischemic heart

disease events leads the epidemiologist on to search

for the dietary and lifestyle determinants of fibrino-

gen. The likely relevance of antioxidants to cancer

and other conditions leads the laboratory worker to

study free radicals and their cellular and other effects,

while the epidemiologist studies the relative protec-

tion given by diets rich in natural antioxidants, and

the effects of dietary antioxidant supplements. The

2144 EPIDEMIOLOGY

hypothesis that the regular consumption of fish is

associated with a low incidence of vascular disease

leads the biochemist to study the metabolism of fish

oils and mechanisms linking fish oils to blood pres-

sure and other cardiovascular risk factors, while the

epidemiologist sets up a randomized controlled trial

of fish eating and the incidence of vascular disease.

The different research approaches – clinical, labora-

tory, and epidemiological – are complementary and

all are needed.

0005 Only the epidemiologist, however, can estimate,

from studies based upon representative population

samples of individuals, the relative importance of

one particular factor to a disease, in comparison

with a host of other relevant factors. Thus, magne-

sium is a key element in many enzymes and is known

to be involved in a large number of metabolic and

other biological mechanisms. Only the epidemiolo-

gist can however estimate the importance of magne-

sium to health and disease in the population, and the

part played by magnesium deficiency, if any, in, say,

cardiovascular disease within a community.

The Concept of Risk Factors

0006 Epidemiologists were probably the first to use the

term ‘risk factor,’ applying it to any factor which

identifies an individual who is at increased risk of a

disease.

0007 The term is however vague and its limitations

should be understood. Thus the term is used to

cover factors which are inherent in a subject and

cannot be altered (such as sex and race, etc.), factors

which are likely to be causal and which can be

changed (such as dietary fat intake, blood pressure,

and plasma fibrinogen) and factors which confound

relationships of interest (such as age and social class).

Factors in this last group are perhaps the most diffi-

cult to identify and deal with. For example, in exam-

ining the relationship between a nutrient and a

disease, calorie intake can often be a confounding

variable, in that it is probably related to the intake

of the nutrient of interest (for most nutrients, the

more food that is eaten, the greater the intake of any

nutrient), and calorie intake, or total energy, is a good

surrogate measure for exercise level which, in turn, is

strongly related to the incidence of vascular and other

diseases.

0008 Another suggested modification of the concept of

‘risk factor’ is to refer to ‘predictors’ of a disease (such

as cholesterol level, blood pressure, plasma fibrino-

gen and other biochemical and hematological factors)

and ‘determinants’ of those predictors (such as diet-

ary fat intake, salt intake, smoking habit, and other

lifestyle and dietary factors). This last grouping has

the great advantage that it acknowledges the differ-

ence between factors involved at the level of meta-

bolic processes, and extrinsic factors, upon which

preventive strategies which are under the control of

subjects themselves, and population-based interven-

tion initiatives, can be focused.

Epidemiological Methods

0009A variety of strategies are used in epidemiology. Ba-

sically these can be divided into prospective and retro-

spective, and into observational and experimental.

Every combination of these is possible: changes over

time; comparisons between communities; individual

case-control comparisons; cross-sectional surveys;

prospective cohort studies; and the randomized con-

trolled trial (RCT) with intervention. Another way in

which the various strategies can be classified is by the

degree of certainty of the conclusions drawn from

them. This last is so important that the various

study designs which are described below are listed in

the order of the likely certainty of the conclusions that

can be drawn from the evidence they yield.

Trends with Time

0010There have been great changes in the mortality of

many diseases, including many cancers and coronary

heart disease (CHD), in most countries during the

past century and it is possible to look for dietary

changes which parallel these changes in disease inci-

dence. Great difficulties arise, however, because infor-

mation on past disease is uncertain and knowledge of

past dietary intakes is very poor. Diagnostic criteria

change, and the attributions of certain causes to

deaths have changed markedly over the years. In

addition, estimates of the nutrient content of food

change, as reflected in food composition tables. The

MONICA study, set up by the World Health Organ-

ization in about 40 countries to study changes over

time in CHD, and in relevant risk factors, is probably

the most ambitious study of this kind ever mounted.

0011Even if reliable data on both diets and disease were

available, the two cannot be linked with certainty

because many other relevant factors may have

changed concurrently. Diet is only one aspect of life-

style and it should never be considered in isolation.

Cross-community Comparisons

0012There are differences in disease rates in different com-

munities and some of these are large. Relating these to

differences in dietary intakes has generated a number

of interesting hypotheses. There are difficulties how-

ever in that the dietary data available for the different

EPIDEMIOLOGY 2145

communities may not be truly representative for

those communities, and the disease data may not be

truly comparable. The biggest stumbling block is the

virtual impossibility of linking differences in disease

incidence to dietary differences since many other

factors – genetic, behavioral, and environmental –

will almost certainly be different and may well be

far more important in determining disease risk than

dietary differences.

Case-control Studies

0013 The identification of patients with evidence of a dis-

ease and the comparison of possible risk factors in

these with the same factors in disease-free subjects is a

basic research strategy. Difficulties arise, however,

because the ‘cases’ are often patients with advanced

disease, who may not be representative of all such

patients. Furthermore, the observer cannot always be

‘blind’ with regard to whether a subject is a ‘case’ or a

‘control,’ and so that bias can easily be introduced

into the data on risk factors. Further difficulties arise

in the selection of suitable control subjects without

the disease, and though some of these difficulties can

be overcome by matching for factors such as sex, age,

and area of residence, uncertainties remain about

comparability between the cases and the controls

with respect to factors other than those believed to

be relevant to the disease.

0014 In nutritional research the case-control strategy has

only a very limited place because it necessitates in-

quiries about dietary intakes before the onset of the

disease, and it is very difficult for a patient to separate

out this information from dietary changes which have

been made since symptoms of the disease com-

menced. Furthermore, the case-control approach has

very little place in diseases with a high case fatality,

such as cancer and heart disease, because only a

selected subsample of all cases survive to be included

in any case-control study and these will certainly not

be representative of all patients with the disease. (See

Cancer: Epidemiology.)

Cross-sectional Survey

0015 One of the most common activities in epidemiology

and in social science is the conducting of surveys.

These can give estimates of the prevalence of a dis-

ease, the distribution of dietary intakes, and the levels

of risk factors, and associations between these can be

examined. For such purposes, it is essential that the

population sample selected for the study is truly rep-

resentative of the community being studied, and that

a high response rate is achieved because otherwise

representativeness will be compromised. Attention

has also to be given to the reproducibility of measure-

ments made. INTERSALT, an international collab-

orative study coordinated by WHO, was a good

example of a cross-sectional study. In this, about 40

research centers obtained data on blood pressure and

on salt excretion from 24-hr urine collections (a sur-

rogate for salt intake) in about 200 subjects per

center.

0016Cross-sectional studies have the great advantage

that all the data collected are contemporaneous, that

is, there is no dependence upon the memories of

subjects, nor is there any waiting for disease to

develop. On the other hand, surveys have the great

disadvantage that causal factors which predated the

onset of the disease cannot always be distinguished

from a factor which has been affected by the disease

itself. Thus, in a cross-sectional survey, differences in

dietary intakes between subjects with CHD and other

subjects, could equally well be the result of changes in

diet made by patients after their heart attack, or the

onset of angina, as the cause of the disease process.

0017One valuable role for cross-sectional surveys is the

identification of determinants of risk factors for dis-

ease. Thus the associations between dietary and other

lifestyle factors and, for example, serum cholesterol,

blood pressure, or serum fibrinogen can be examined.

Prospective Studies

0018The prospective, cohort, or longitudinal study is the

classic tool of the epidemiologist. In this, a representa-

tive population sample of subjects (a cohort) is exam-

ined and then followed forward in time. The

association between the levels of the various factors

measured at baseline, and the development of the

disease, is examined. In other words, the predictive

power for subsequent disease of dietary, lifestyle, bio-

chemical, hematological, and other factors is exam-

ined. The great advantage of this strategy is that the

suspected causal factors are measured before the dis-

ease becomes evident, and causal factors can therefore

be distinguished from factors which represent effects

of the disease.

0019The identification of factors showing greater than

chance associations with subsequent disease is how-

ever not the final answer. The degree to which the

predictive power of a factor for the disease is inde-

pendent of other factors must be examined. Thus, on

first analysis the dietary intakes of many dietary

factors is likely to be found to be predictive of a

range of diseases. It must be examined whether or

not such relationships are simply a consequence of

an age effect (older subjects having an increased risk

of most diseases and, probably, a reduced intake of

most nutrients) or due to confounding by smoking

2146 EPIDEMIOLOGY