Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

volatile fatty acids butyrate, propionate, and acetate.

Whereas the gut of ruminants is adapted to provide a

watery, nutrient-rich environment for bacterial fer-

mentation in the foregut, the colon is the main site

of permanent bacterial colonization in the human

alimentary tract. The proximal colon contains about

200 g of dilute fecal material, portions of which are

transferred at regular intervals from the right colon

into the transverse and distal segments for partial

dehydration and storage. The pattern of motility in

the large intestine is similar in principle to that of the

rest of the alimentary tract, but the rate of transit is

slower. In healthy individuals, stools are passed with a

frequency varying from once or twice a day to once

every 2–3 days.

0010 The absorption and metabolism of short-chain

fatty acids derived from carbohydrate fermentation

provide an important route for the recovery of energy

from undigested polysaccharides. Butyrate functions

as a source of energy for the colonic mucosal cells,

whereas propionate and acetate are absorbed and

metabolized systemically. The other major break-

down products of carbohydrate fermentation are

hydrogen, methane, and carbon dioxide, which to-

gether comprise flatus gas. Excess gas production

is said to cause distention and pain in some individ-

uals, especially those attempting to increase their

fiber consumption, but this is probably caused

more by fermentation of oligosaccharides such as

stachyose and verbascose, found for example in

legume seeds, rather than the cell wall polysac-

charides themselves.

Fecal Bulk

0011 The ability of dietary fiber to prevent cancer and

various degenerative diseases of the alimentary tract

was proposed by Denis Burkitt, who based his hy-

pothesis largely on the concept of fecal bulk. His field

observations in Africa, where cancer and other

chronic bowel diseases were rare, suggested that

populations consuming traditional rural diets rich in

vegetables and cereal foods produced bulkier, more

frequent stools than persons living in the industrial-

ized West. Burkitt argued that consumption of highly

processed cereals in industrialized societies led to

chronic constipation, and that this caused prolonged

high pressures both within the colonic lumen, and

also within the lower abdomen as a result of straining

to pass hard stools. This in turn was thought to in-

crease the risk of various diseases of muscular degen-

eration including varicose veins, hemorrhoids, hiatus

hernia, and colonic diverticuli. Furthermore, infre-

quent defecation was thought to cause prolonged

exposure of the colonic epithelial cells to mutagenic

chemicals that could initiate cancer. Although

Burkitt’s overall hypothesis for the beneficial effects

of fecal bulk is undoubtedly an oversimplification, it

has never been comprehensively refuted.

0012It is certainly true that the consumption of dietary

fiber is a major determinant of both fecal bulk and

bowel habit, but the magnitude of the effect depends

upon the type of fiber consumed. Soluble cell wall

polysaccharides such as pectin are readily fermented

by the microflora, whereas lignified tissues such as

wheat bran tend to remain at least partially intact in

the feces. Both classes of dietary fiber can contribute

to fecal bulk but by different mechanisms. The incre-

ment in stool mass caused by wheat bran depends to

some extent on particle size, but in healthy Western

populations, it has been shown that for every 1 g of

wheat bran consumed per day, the output of stool is

increased by between 3 and 5 g. Other sources of

dietary fiber also favor water retention. For example

isphagula, which is a mucilaginous material derived

from Psyllium, is used pharmaceutically as a bulk

laxative. Soluble polysaccharides such as guar and

oat b-glucan are readily fermented by anaerobic

bacteria, but solubility is no guarantee of ferment-

ability, as is illustrated by modified cellulose gums

such asmeythylcellulose, which is highly resistant to

degradation in the human gut. Fermentation reduces

the mass and water-holding capacity of soluble

polysaccharides considerably, but the bacterial cells

derived from them do make some contribution to

total fecal output. Thus, although all forms of dietary

fiber exert some laxative effect, the important differ-

ences in their properties and behavior make it hazard-

ous to infer the biological effects of any diet from a

single analytical measurement of total fiber content.

Fecal Chemistry

0013Apart from increasing the availability of energy from

dietary fiber, the major effect of bacterial fermenta-

tion is to regulate the physical and chemical properties

of the intraluminal environment. It is now generally

accepted that most colorectal carcinomas develop

progressively from precancerous lesions called adeno-

matous polyps. The gradual transition from a normal

crypt via a precancerous lesion to a malignant tumor

is associated with a progressive loss of differentiation,

deregulation of cell growth, and an accumulation of

mutations in genes associated with the control of cell

proliferation and death. These somatic mutations

are assumed to be caused primarily by mutagenic

chemicals in the feces, much as mutagens in tobacco

smoke induce lung cancer. Human fecal water con-

tains a number of different mutagens that have

been shown to be carcinogenic in animals. These

include heterocyclic aromatic amines created during

the cooking of meat at high temperatures, and

1836 DIETARY FIBER/Physiological Effects

N-nitrosamines derived from dietary proteins. It has

not been established conclusively that these sub-

stances cause colorectal carcinogenesis in humans,

but there is strong circumstantial evidence that they

do, and it would seem prudent to adopt nutritional

strategies to reduce their concentration in the colon.

The fecal bulking hypothesis provides the principal

rationale for the current Dietary Reference Values for

nonstarch polysaccharides in the UK, which recom-

mend that adults should consume an average of 18 g

of fiber per day. Epidemiological studies provide only

weak evidence for a protective effect of dietary fiber

against bowel cancer within the populations of indus-

trialized Western countries such as the USA, perhaps

because the overall range of fiber intakes is relatively

low. However, there is stronger evidence for a pro-

tective effect of fiber intake and fecal weight against

bowel cancer when different populations with a

broader range of fiber intakes are compared.

0014 The realization that colorectal carcinogenesis is a

prolonged multistage process involving changes to a

complex array of genes raises new questions about

interactions between the colonic epithelial cells, diet-

ary fiber, and other constituents of the fecal stream.

Bile acids, which are produced by the liver and

secreted into the gut lumen, where they facilitate the

digestion and absorption of fat, are known to increase

the rate at which colonic mucosal cells divide. It has

been proposed that this effect causes bile salts to act

as tumor promoters in the human colon, and thereby

helps to accelerate the carcinogenic process initiated

by fecal mutagens. High-fat diets tend to stimulate

the release of bile acids and increase their concen-

tration in the feces, and this may explain at least

partially the fact that high fat consumption is a risk

factor for bowel cancer in human populations. How-

ever, increased fecal bulk will tend to dilute the con-

centration of bile salts and reduce their residence

time. The nonfermentable particulate components of

plant cell walls may also provide a finely dispersed

solid phase on to which bile acids can bind, so that

their concentration in the aqueous phase of the feces

is reduced still further. (See Cancer: Diet in Cancer

Prevention.)

Cellular Physiology

0015 Fermentation of carbohydrates lowers the pH of the

feces and increases the concentration of short-chain

fatty acids in contact with the mucosal cells. There is

increasing evidence that these changes modify the

intraluminal environment in such a way as to regulate

the birth and death of the mucosal cells. Programmed

cell death (apoptosis) is a mechanism whereby dam-

aged cells are removed selectively from a tissue in an

orderly manner that does not cause inflammation or

general tissue desruction. This may well provide a

defense against the survival of cells carrying tumori-

genic mutations. Apart from the role of butyrate as an

essential source of energy for the colonic mucosa, it

also suppresses proliferation, increases differenti-

ation, and induces apoptosis in many types of tumor

cell grown in vitro. Tumor cell lines established from

adenomatous polyps and carcinomas from human

colon undergo increased apoptosis in the presence of

butyrate, at concentrations close to those that occur

in vivo. Moreover, cells from fully developed carcin-

omas have been shown to be less responsive to butyr-

ate than those from early lesions, which perhaps

implies that abnormal cells that survive and evolve

into malignant tumors also acquire an adaptive resist-

ance to butyrate. Unabsorbed starch and fermentable

components of cereal fiber may provide a source of

increased butyrate, which helps to suppress the pro-

liferation of tumor cells and increase the likelihood

of their deletion from the tissue by apoptosis. If so,

much may depend on the rate of fermentation. Sugars

and small oligosaccharides probably disappear too

rapidly after entering the colon to provide a supply

of butyrate to the distal colorectum, whereas lignified

plant cell walls and some types of resistant starch that

are slowly fermented may deliver butyrate efficiently

to more distal regions of the colonic mucosa.

Adverse Physiological Effects

0016There are few well-authenticated adverse effects of

dietary fiber. Some cases of pediatric malnutrition

caused by very high fiber intakes have been reported,

but this problem appears to be confined to grossly

unbalanced diets. Similarly, the few cases of gastro-

intestinal obstruction in the literature appear to stem

from very abnormal intakes of wheat bran or from

swallowing nonhydrated supplements of viscous

polysaccharides intended for consumption as a drink.

There is some evidence that patients with a history

of gastrointestinal surgery are at increased risk of

obstruction due to abnormally high intakes of cereal

bran. (See Inflammatory Bowel Disease.)

Sources of Fiber

0017It should now be obvious that although all plant

foods provide some form of dietary fiber, not all

components of fiber have the same physiological

effects. In the UK, about 47% of total fibre intake is

obtained from bread of various types and from break-

fast cereals. The level of fiber in bread depends upon

the extraction rate, which is the proportion of the

original grain used to make flour. White flour has an

extraction rate of about 70% and contains about 3%

DIETARY FIBER/Physiological Effects 1837

nonstarch polysaccharides (NSP), whereas ‘whole-

meal’ (100% extraction) flour contains about 10%

NSP. Wheat bran, which contains about 40% NSP,

can be added to the diet as a supplement, but it is

relatively unpalatable. One of the lasting effects of

the dietary fiber hypothesis has been to increase the

variety and palatability of high extraction cereal

products in the market place. Such products tend to

contain primarily insoluble, poorly fermentable poly-

saccharides, and their consumption is a very effective

way of increasing fiber intake to increase stool bulk.

Oats, rye and barley contain higher quantities of

soluble fiber than wheat. Oat bran is an important

source of b-glucan, a soluble viscous polysaccharide

that has been shown to slow down glucose absorption

and reduce plasma low-density lipoprotein choles-

terol levels in humans. A further 45% of total

fiber intake in the UK comes from fruits and vege-

tables. Typically, the levels of NSP in fruits and

vegetables are between 1 and 5% of fresh weight,

and the polysaccharides are mostly soluble pectins

and arabinoglactans, which are readily fermentable

in the large bowel. For reasons described earlier, sol-

uble fiber from vegetables and fruit does not have the

bulk laxative effect of cereal bran, but it does provide

fermentable carbohydrate for fermentation in the

colon. Moreover, there is strong evidence that fruit

and vegetables protect against cancer through other

mechanisms, including the provision of biologically

active phytochemicals. (See Dietary Fiber: Properties

and Sources.)

See also: Cancer: Diet in Cancer Prevention;

Carbohydrates: Metabolism of Sugars; Dietary Fiber:

Properties and Sources; Inflammatory Bowel Disease;

Phytic Acid: Nutritional Impact

Further Reading

Burkitt DP and Trowell HC (eds) (1975) Refined Carbo-

hydrate Foods: Some Implications of Dietary Fibre.

London: Academic Press.

Bell S, Goldman VM, Bistrian BR et al. (1999) Effect of

beta-glucan from oats and yeast on serum lipids. Critical

Reviews in Food Science and Nutrition 39: 189–202.

Johnson IT and Southgate DAT (1994) Dietary Fibre and

Related Substances. London: Chapman & Hall.

Kushi LH, Meyer KA and Jacobs DR Jr (1999) Cereals,

legumes and chronic disease risk reduction: Evidence

from epidemiologic studies. American Journal of

Clinical Nutrition 70: 451S–458S.

Southgate DAT (1992) Determination of Food Carbohy-

drates, 2nd edn. London: Elsevier Applied Science.

Williams GM, Williams CL and Weisburger JH (1999) Diet

and cancer prevention: The fibre first diet. Toxicological

Science 52: 72–86.

Effects of Fiber on Absorption

L Prosky, Prosky Associates, Rockville, MD, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Although dietary fiber is not in itself a nutrient, in

many countries, it is considered among the six groups

of major nutrients along with proteins, carbohy-

drates, fats, vitamins, and minerals. Its required

listing on the nutrient food label in most countries

that have labeling procedures begs the question:

what is the function of dietary fiber? Among these

concerns is: how does the speeding up of the pas-

sage of food through the gastrointestinal tract and

increase in the stool weight caused by the ingestion

of diets high in dietary fiber affect the absorption

of nutrients and other substances in the gastro-

intestinal tract?

Effects on Mineral Absorption

0002In vitro studies have shown that particular fibers bind

minerals such as iron and zinc, suggesting interfer-

ence of fibers on mineral absorption. Iron deficiency,

which is one of the most prevalent deficiency dis-

orders in the world, is present in Western cultures

where there is no lack of food. There would also be

concern for many of the other minerals for which

there is only a marginal dietary intake. Some reports

have implicated bran as a very strong iron absorption

inhibitor, the action of which could be reversed with

ascorbic acid or dietary meat (Table 1). High intake

of phytate-rich, fiber-rich foods could inhibit zinc

absorption, but again, this could be reversed by inges-

tion of animal protein. This would seem to indicate

that there are many other factors involved in the

absorption of minerals. In addition, several reports

have revealed a tendency for reduced absorptions and

retentions to occur for calcium, magnesium, phos-

phorus, and copper. It should be noted that no reliable

method exists for measuring the bioavailability of an

ingested mineral that separates this exogenous intake

and its associated biological response from the

amount of endogenous mineral in the body being

reabsorbed and reutilized. Further, it has remained a

challenge to detect a biological response sensitive

enough to measure a change in the body’s storage or

use of a mineral that reflects the true amount of a

specific dietary mineral absorbed or utilized. These

problems are further compounded when the inter-

actions among minerals are considered. The draw-

back to many of the studies was the relatively short

period of observation and the often excessively high

1838 DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption

dosage of the particular experimental component.

The intakes of dietary fiber foods often bear little

relationship to human dietary situations (as much as

60 g per day of bran supplements in some studies). It

also has been demonstrated that there is an adapta-

tion to decreased mineral intake. Ingesting 50–60 g of

dietary fiber derived from whole maize meal, brown

bread, and beans with a mean daily intake of 275 mg

of calcium resulted in calcium absorption varying

from 61 to 83%. This is far higher than the usual

20–30% absorption that occurs with Western sub-

jects ingesting much lower dietary fiber diets. The

results showed that the subjects were in balance

with regard to calcium, magnesium, and iron, and

that the drawbacks of habitually high dietary fiber

intakes and low calcium and other mineral salt

intakes of Third World people may be of less signifi-

cance to health than might be expected. While the

nutritional policies of Western societies should not do

anything to restrict, at this time, the intake of dietary

fiber-containing food, it is apparent that as the world

population increases, there will be a greater reliance

on plant foods. This is because it is far more econom-

ical to use land to produce plant products than to

produce meat products. More work will obviously

have to be done to establish the mineral absorption

effects and the factors that affect them (i.e., phytate,

etc.), but for now, the benefits of ingesting dietary

fiber far outweigh any negative effects of decreased

mineral absorption. Also included in Table 1 are

the mineral absorption effects of four food com-

ponents; the methods for these food components were

approved recently by the Association of Official Ana-

lytical Chemists (AOAC). These food ingredients are

not measured as dietary fiber by the standard AOAC

methods for dietary fiber but are carbohydrate poly-

mers of DP-3 and higher and are resistant to hydroly-

sis and absorption in the human small intestine.

Updated definitions of dietary fiber include these

components (See Minerals – Dietary Importance.)

Effects on Vitamin Absorption

0003There is a paucity of information on the availability

of vitamins in relation to the dietary fiber content of

the diet. Further, what is available is mainly from

animal studies, and the extrapolation of its effects to

humans may be difficult.

0004In previous studies, methyl cellulose or pectin did

not affect the utilization of vitamin A in rats, but a

combination of the two did appear to decrease liver

vitamin A stores. Lignin given with a test meal did not

affect serum vitamin A of human subjects, but carot-

ene, which is bound to plant cell walls, is less avail-

able than pure or added carotene. (See Carotenoids:

Physiology; Retinol: Physiology.)

tbl0001 Table 1 Effect of various dietary fibers on the absorption of five essential minerals

Dietary fiber Iron Calcium Zinc Phosphorus Magnesium

Bran ##

Ispagula #

Psyllium # ne

Pectin ne ne ne

Methoxylate pectin ne

Guar gum ne

Cellulose ne # ne #,ne

Beet pulp ne

Brown bread #* #

a

,ne #

a

,ne

Unpolished rice #

a

#

a

Unleavened wholemeal bread # ne

Leavened wholemeal bread ###

Wheat fiber #

Cellulose in apple compote # ne #

Hemicellulose #

Fruits, vegetables #,ne ne #,ne

Partially hydrolyzed guar gum (Sunfiber

1

) "" "

Pectin ne ne ne ne ne

Cellulose ne ne ne ne ne

Inulin, oligofructose

b

"" "

c

"

Galactooligosaccharides

b

""

Resistant maltodextrin (Fibersol-2

1

) ne " ne

Polydextrose

b

ne

#, decreased absorption; #

a

, decreased absorption improved with time; ne, no effect; ", increased absorption;

b

, at present time is not measured as fiber;

c

, prevents phosphorus loss from bone not observed

DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption 1839

0005 Dietary methyl cellulose had no effect on the

growth of thiamine-deficient or normal rats. Ribofla-

vin and niacin may be less available from wholemeal

bread than from enriched white bread. Several fiber

sources (course bran, fine bran, cellulose, and cab-

bage) improved absorption of a load dose of ribofla-

vin in humans. Nicotinic acid, which is bound to fiber

in cereal brans and is not available unless released

by alkaline hydrolysis or treatment with limewater,

was rendered effective in promoting weight gain in

animals, made deficient by feeding maize with bound

vitamin. The binding was probably due to cellulose or

hemicelluloses. (See Niacin: Physiology.)

0006 A lower bioavailability of vitamin B

6

from cereal

than from nonfat dry milk was reported for rats.

Vitamin B

6

was available to a lesser degree from

soybeans than from beef, and the addition of wheat

bran to a diet increased vitamin B

6

availability in

human subjects. Fibers digestible by intestinal bac-

teria (xylan, guar gum, and pectin) intensified the

symptoms of B

12

depletion in rats as compared with

the nondigestible fibers (cellulose, lignin, alginate,

and wheat bran). (See Vitamin B

6

: Physiology.)

0007 In two additional studies, fiber (in the form of

white bread, wholemeal bread, or cellulose) was

found to have no effect on urinary folate excretion,

but in another study, fiber (maize, rice, and bread)

decreased the elevation in serum folate as compared

with the vitamin alone. (See Folic Acid: Physiology.)

0008 From these inadequate data, it appears that in

general, the availability of unbound vitamins is not

affected by the presence of dietary fiber, but the

situation with the bound vitamins will have to be

explored further.

Effects on Lipid Absorption

0009 Dietary fiber can influence lipidemia and atheroscler-

osis by affecting the absorption and metabolism of

the lipid components in the blood. Soluble fibers,

such as pectin, do affect the lipid uptake and glyce-

mia. Oat bran, which contains b-glucans (soluble

fibers), will lower the level of serum cholesterol. It is

now established that, whereas insoluble dietary fibers

(wheat bran, cellulose) do not influence serum lipids,

soluble dietary fibers (guar, pectin, psyllium) exert a

hypocholesterolemic effect (Table 2). The mechanism

by which this hypocholesterolemic effect is exerted

involves increased viscosity of the stomach and small

intestine contents, and may also influence bile acid

metabolism.

0010 Cereal fibers and fractions (oat, rice, and barley)

contribute significantly in reducing total cholesterol

in a variety of animal species and in hypercholester-

olemic subjects. Long-term population studies

(Framingham, LRC, and Helsinki) have demon-

strated that for each 1% reduction in total choles-

terol, there is a two- to fourfold decrease in

atherosclerosis in otherwise healthy individuals. A

6-year prospective study of male health professionals

diagnosed free of cardiovascular disease showed that

cereal fiber was found to be most strongly associated

with a reduced risk of myocardial infarction. Adding

oat and barley, in addition to other soluble dietary

fiber foods, proved efficacious in lowering cholesterol

even further. The data generated by some 60 feeding

studies with psyllium convinced the US Food and

Drug administration to approve a health claim for

psyllium, which allows foods and supplements with

at least 1.7 g of soluble dietary fiber from psyllium to

claim ‘soluble fiber from psyllium per serving, as part

of a diet low in saturated fat and cholesterol, may

reduce the risk of heart disease.’ Although the effects

of cereal fiber are less pronounced in normo-choles-

terolemic individuals, these changes would have a

significant impact on reducing cardiovascular risk

for the whole population. Table 3 shows the effects

of feeding various dietary fibers on serum and liver

cholesterol and serum triglycerides in a rat model. Of

particular interest is cellulose, which has no effect on

cholesterol and triglycerides, and wheat bran, which

has little effect on serum and liver cholesterol but

plays a role in reducing serum triglycerides.

0011To date, the FDA has approved health claims for

three substances, oats, psyllium and soy, with regard

to their cholesterol-lowering ability in combination

with a diet that is low in saturated fat and cholesterol.

This reinforces the abundant data available showing

the cholesterol-lowering properties of specific dietary

fibers. A study was done to compare a soluble fiber,

soy-enhanced diet with a diet containing low-fat

dairy foods but low in soluble dietary fiber on the

level of serum lipids. The test diet reduced the total

cholesterol:high-density lipoprotein (HDL)-choles-

terol ratio and reduced the risk of coronary heart

tbl0002Table 2 Influence of dietary fibers on human serum total and

low-density lipoprotein (LDL)-cholesterol (percentage of control)

Dietary fiber Total cholesterol LDLcholesterol

Wheat bran 102 97

Corn bran 97 98

Cellulose 104 108

a

Soy hulls 107 104

Oat bran 87

a

86

a

Guar gum 87

a

84

a

Locust bean gum 86

a

86

a

Gum karaya 90

a

90

a

Legumes 87

a

95

a

Significant effects.

1840 DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption

disease (CHD). (See Cholesterol: Factors Determin-

ing Blood Cholesterol Levels.)

0012 In a study of the relationship of dietary fiber

and serum lipids among true vegans, lacto-ovo-

vegetarians, nonvegetarians, and the general public,

only the true vegans showed a significant lowering of

cholesterol. The only difference in the dietary fiber

intakes among the four groups was a higher intake of

pectin in the true vegans.

0013 The digestion of dietary fat begins in the stomach,

where it is coarsely emulsified and partially hydro-

lyzed. No further emulsification occurs in the duode-

num, but subsequently, under the action of pancreatic

lipase, phospholipids and cholesterol esters are

cleaved enzymatically. The activity of pancreatic

lipase in vitro can be reduced by several of the soluble

dietary fibers, including pectins, oat bran, psyllium,

and sugar beet fiber, with part of the loss being due to

the binding of the fiber to the enzymes. The inhibitory

effects of insoluble dietary fibers, wheat bran, and

wheat germ can also produce this reduction of

pancreatic lipase. Because the mechanism by which

soluble dietary fibers alter the breakdown of fat is not

well understood, some investigations of the physico-

chemical aspect of the process were studied. It is well

known that emulsification is a key step in fat diges-

tion, because gastric and pancreatic lipases act at the

fat globule–water interface, and that the size of the fat

globule is a parameter governing the activity of

gastric and pancreatic lipases. Could dietary fiber

intefere with the normal process of fat emulsification?

The two parameters studied were viscosity and

electric charge. Five sources of fiber with different

properties were studied, namely gum arabic (not vis-

cous), two differently charged pectins, and three un-

charged guar gums (of varying viscosity). Under

gastric conditions (pH 5.4), the degree of emulsifica-

tion was not affected by any of the fibers, but the

viscous fibers did increase the size of the emulsified

droplets, and the effect was more pronounced as the

concentration of these fibers increased. Only viscous

fibers significantly increased droplet size and reduced

droplet surface area. Overall, the droplet size was

positively correlated, and the droplet surface area

was negatively correlated with the concentration of

the medium viscosity guar gum in the range 0–

20 mPa.s. The high-viscosity guar gum significantly

reduced (by 32%) the triglyceride lipolysis of such

emulsions by human gastric lipase, compared

with control and low- and medium-viscosity fibers

(Table 4).

0014In duodenal conditions (pH 7.5 and addition of

bile), the quantity of emulsified lipids was reduced,

and raising the concentration of viscous fibers in-

creased the size of the droplets. The extent of the

emulsification, the droplet size, and, consequently,

the droplet surface area were strongly correlated

with the concentration of the medium-viscosity guar

gum in the range 0–4 mPa.s. (and also 0–20 mPa.s.).

The high- and medium-viscosity guar gums and one

type of pectin significantly reduced the extent of tri-

glyceride lipolysis catalyzed by pancreatic lipase only.

Overall, the extent of triglyceride lipolysis was nega-

tively correlated with the viscosity of the duodenal

medium. These findings indicate a mechanism by

which soluble, highly viscous fibers can alter lipid

assimilation by lowering the emulsification of dietary

lipids in the stomach and duodenum.

0015This hypothesis was tested in vivo in rats. A

coarsely emulsified lipid mixture with and without

0.3% high-viscosity guar gum was intragastrically

intubated. After 30 min of digestion in the stomach,

the median droplet diameter of the emulsion in the

presence of guar gum was about two fold larger. The

specific surface area displayed by the emulsion was

about half that of the controls. In the presence of the

guar gum, the extent of triglyceride lipolysis was

about threefold lower in the stomach content and

about twofold lower in the duodenum content.

Thus, dietary fibers that raise viscosity in the stomach

and duodenum contents reduce the extent of emulsi-

fication and subsequent triglyceride lipolysis.

tbl0003 Table 3 Effect of feeding various dietary fibers on serum and liver cholesterol and serum triglycerides in rat models

Dietary fiber Number of studies Serum cholesterol

(percentage change)

Liver cholesterol

(percentage change)

Serum triglycerides

(percentage change)

Psyllium 7 32 52 9.6

Oat gum 11 22 45 9.6

Guar gum 3 23 43 na

Pectin 20 17 35 þ3.2

Oat bran 8 12 28 13.4

Soy fiber 6 11 17 10.2

Corn bran 2 6 11 43.9

Cellulose 26 0 0 0

Wheat bran 5 1 þ6 38

na, not available.

DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption 1841

0016 The lipid products of the digestion process

(i.e.,mainly monoglycerides, free fatty acids, lysopho-

spholipids, and free cholesterol) are absorbed by the

small intestine, where they are rapidly used as sub-

strates for the de-novo synthesis of triglycerides,

phospholipids, and cholesterol esters. They are then

packaged and secreted as chylomicrons into the

lymph and finally into the blood.

0017 Other mechanisms can contribute to the absorp-

tion of lipids. The binding or entrapment of lipolytic

products as well as bile salts in the presence of viscous

fibers such as oat bran, guar gum, and pectin can

counteract the building of vesicles and mixed micelles

in the aqueous phase of the small intestine contents.

The limiting step in lipid absorption is the transport

across the unstirred water layer associated with the

enterocyte brush-border membrane. Highly viscous

fibers have been observed to increase the thickness

of the unstirred layer, reducing the rate of diffusion

and absorption of cholesterol and free fatty acids.

These effects have not been observed in the presence

of slightly viscous soluble fibers (hydrolyzed guar

gum, or chitosan) or insoluble fibers such as cellulose

or some hemicelluloses. Changes induced in the intes-

tinal lumen by feeding viscous fibers have been shown

to result in reduced recovery of fatty acids and chol-

esterol in the lymph.

0018 Augmented ileal excretions of lipids have been re-

peatedly demonstrated in ileostimized human sub-

jects after ingesting meals containing citrus pectin,

alginate, oat bran, or b-glucan, and barley fiber.

Some investigators have also reported increased

fecal or ileal lipid excretions after their subjects’

diets were enriched with wheat bran or wheat germ.

The ileal or fecal excretion of cholesterol and/or bile

acids is markedly increased after addition of various

kinds of dietary fibers are added to the test diets.

Soluble and viscous fibers such as b-glucans, pectin,

or psyllium are particularly efficient in increasing

cholesterol excretion,

0019A principal feature of the postprandial state is a

striking increase in triglyceridemia, owing to the se-

cretion of chylomicrons (which transport absorbed

dietary lipids and cholesterol) by the small intestine

into the circulatory system. Studies with a variety of

diets, either supplemented or not supplemented, has

shown that different kinds of dietary fibers (wheat

fibers, legume fibers, guar gums, pectins, oat bran,

b-glucans, psyllium, and mixed fibers, especially

those rich in soluble fibers) can reduce the postpran-

dial rise in triglyceridemia. This results from reduced

bioavailability of fatty acids and cholesterol induced

by the viscous dietary fibers, making the small intes-

tine mucosa less efficient in lipid synthesis and in

secreting chylomicrons into the lymph and finally

into the circulatory system.

0020Partially hydrolyzed guar gum lowers total choles-

terol, triglycerides and LDL with no change in the

HDL in human subjects. Hemicelluloses from soft

winter wheat, hard red spring wheat, corn bran, soy

hulls, apples, and carrots lowers triglyceride levels,

but only the hemicellulose from soft winter wheat had

no effect on serum cholesterol. This indicates that the

effects may be dependent of chemical interactions

with other nutrients in the foods.

0021Several of the carbohydrate dietary components

that are not measured as dietary fiber in any of the

accepted methods, but which are not digested or

absorbed in the small intestine, appear to have the

physiological effects that we have come to identify as

tbl0004 Table 4 Influence of dietary fiber charge and viscosity on droplet size, droplet area, and triglyceride lipolysis under gastric and

duodenal conditions

Dietary fiber Droplet size Droplet surface area Triglyceride lipolysis

Gastricconditions(pH5.4)

Gum arabic (not viscous)

Pectin (low viscosity, charged) þ#

Pectin (low viscosity, different charge) þ#

Guar gum (low viscosity, uncharged) þ##

Guar gum (medium viscosity, uncharged) þþ ###

Guar gum (high viscosity, uncharged) þþþ #### #

Duodenal condition (pH 7.5 and addition of bile)

Gum arabic (not viscous)

Pectin (low viscosity, charged) þ#

Pectin (low viscosity, different charge) þ#

Guar gum (low viscosity, uncharged) þ##

Guar gum (medium viscosity, uncharged) þþ ## #

Guar gum (high viscosity, uncharged) þþþ ### #

, no effect; þ, increase effect; #, decreases surface area; #, decreases lipolysis.

1842 DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption

fiber effects and have received much attention re-

cently. They have the following properties with

regard to lipid absorption (Table 5).

Effects on Carbohydrate Absorption

0022 The rate of delivery of glucose by the gut to the portal

vein and the peripheral tissues is influenced by many

factors other than the amount of a-linked glucose

polymers in foods. The amylose:amylopectin ratio in

starchy foods influenced postprandial glycemia, be-

cause amylopectin had a much faster rate of hydroly-

sis by pancreatic a-amylase. Food that was not

chewed resulted in a much flatter glycemic response

than food that was chewed well before swallowing.

Similar responses could be found when food was

altered through milling of cereals, indicating the im-

portance of structure and particle size affecting the a-

amylase access to the starch substrate and the effects

of surface area. Food constituents such as dietary

fiber, which form viscous solutions, may slow the

rate of starch digestion and hence glucose absorption.

The mechanism of the effects of a viscous solution

might happen because of (1) delayed gastric empty-

ing; (2) reduced hydrolytic activity; (3) poor mixing

of the intestinal contents with the secreted enzymes;

and/or (4) increased thickness of the unstirred water

later, slowing down the diffusion of glucose.

0023 The concept of a glycemic index (GI) was intro-

duced in 1981 as a measure of the rise in postprandial

glucose of various food carbohydrates. Low-GI foods

were found to be slowly or incompletely digested in

the small intestine, or found to contain fructose,

which is only partially converted to glucose. On the

basis of this determination, foods such as unripe

bananas (rich in amylose) and over-ripe bananas

(rich in fructose) had a lower GI than fresh white

bread, which is the standard against which the GI of

other foods is measured.

0024 Starch in freshly cooked potatoes is readily hydro-

lyzed by a-amylase and results upon feeding in a high

glycemic and insulinemic response. Repeated cooking

and cooling of these potatoes increases the amount of

starch resistant to the a-amylase of the small intestine.

The result of feeding freshly cooked potatoes and

potatoes that had been cooled and cooked several

times was a higher postprandial peak for plasma

glucose and serum insulin in the former group. (See

Starch: Functional Properties.)

0025In subsequent years, interest has been shifted to the

effects of viscous fibers on glucose absorption by the

small intestine and insulin release by the pancreas. It

has been shown that insoluble fiber sources such as

wheat bran had little effect on glucose tolerance and

postprandial insulin response. The effects of viscous

fibers were striking and depended on the viscosity of

the fiber. Oat b-glucan clearly showed this effect,

which was similar to sipping glucose over 3 h, rather

than ingesting it as a bolus in 5 min. The nibbling

versus gorging effect has been shown to be of benefit

in diabetes.

0026The chemically resistant starches have no effect on

the glycemic response of the available starch. These

starches are chemically resistant and require solubil-

ization with potassium hydroxide prior to analysis.

Entrapped starch, which may be physically trapped

in, or by, the fiber reacts as a slow-release carbohy-

drate. This starch simply needs to be released from its

bound physical matrix and made available by good

mastication or fine grinding of the food ingredient.

0027Fructooligosaccharides have no major effects on

the glycemic response of the accompanying carbohy-

drate and have no effect on the glycemia per se.

0028Dried legumes peas, beans and lentils, pumpernikel

rye bread, and bulgur or cracked wheat have been

shown to reduce the rate at which these foods are

digested, and therefore improve the glucose tolerance.

The structure of the food may also influence the rate

at which the foods are digested.

0029Paradoxically, insoluble dietary cereal fiber have

been shown to offer protection from diabetes in sev-

eral large cohort studies. Low-GI diets or diets with a

low glycemic load (dietary GI dietary carbohy-

drates) were also found to be related to the develop-

ment of Type 2 diabetes over a 6-year period. It is not

easy to explain why cereal fiber has an effect in redu-

cing Type 2 diabetes, unless it is through associated

nutrients such as magnesium or antioxidants. While

the effects of wheat bran on glycemia are not striking,

it is possible that the phenolics in the bran may be

useful antioxidants of importance in the prevention of

diabetes.

0030The early promise shown by viscous soluble dietary

fibers in the treatment of diabetes has suffered be-

cause of the unavailability of palatable soluble dietary

fiber diets. Studies using the insoluble dietary fibers

from cereal have not been followed up successfully in

more recent studies.

tbl0005 Table 5 Effects of food constituents on lipid parameters

Product TCTRLDLHDLBF

Inulin and oligofructose #

a

#

a

Polydextrose #

a

#

a

Galactooligosaccharides #

Resistant maltodextrin

(Fibersol-2

1

)

## ne #

TC, total cholesterol; TR, triglycerides; LDL, low-density lipoprotein; HDL,

high-density lipoprotein; #

a

, lowers in hypercholestorolemics; BF, body

fat; ne, no effect.

DIETARY FIBER/Effects of Fiber on Absorption 1843

0031 Table 6 lists the effects of five food constituents on

postprandial carbohydrate parameters. Only the par-

tially hydrolyzed guar gum and resistant maltodex-

trin measure as dietary fiber by the AOAC method.

Effect on Protein Absorption

0032 The effects of dietary fiber on protein absorption

have mostly been ignored. Studies have shown that

the increased intake of dietary fiber results in in-

creased nitrogen loss. The form in which the nitrogen

occurs in the feces is of considerable importance, if

one is trying to deduce the effects of a dietary com-

ponent on digestion.

0033 Investigations in which the fecal nitrogen was frac-

tionated imply that most of the nitrogen is in the

bacterial mass or metabolic products, such as bacter-

ial products, unabsorbed intestinal secretions, or

mucosal cell debris. The proportion derived from

unabsorbed dietary components represents a loss to

the body, which is probably an effect of absorption of

protein. There is also evidence that some bacterial

nitrogen is derived from urea secreted in the large

bowel and some fixation of nitrogen occurs in the

large bowel. These uncertainties emphasize the

limited value of fecal data for deducing what are

essentially intestinal events. The probable solution

to this problem would be to carry out ileostomy

studies. To date, ileostomy studies centered on pro-

tein absorption have not been carried out.

See also: Carbohydrates: Digestion, Absorption, and

Metabolism; Dietary Fiber: Physiological Effects; Fats:

Digestion, Absorption, and Transport; Minerals – Dietary

Importance; Protein: Digestion and Absorption of Protein

and Nitrogen Balance; Vitamins: Overview

Further Reading

Cho SS, Prosky L and Dreher M (eds) (1999) Complex

Carbohydrates in Foods. New York: Marcel Dekker.

Kritchevsky D and Bonfield C (eds) (1995) Dietary Fiber in

Health and Disease. St. Paul, MN: Eagan Press.

Kritchevsky D and Bonfield C (eds) (1997) Dietary Fiber in

Health and Disease. New York: Plenum Press.

Lairon D (2001) Dietary fibres and dietary lipids. In:

McCleary BV and Prosky L (eds) Advanced Dietary

Fibre Technology. London: Blackwell Science.

McCleary BV and Prosky L (eds) (2001) Advanced Dietary

Fibre Technology. London: Blackwell Science.

Marabou Food and Fibre (1976) Symposium held at Mara-

bou, Sundbyberg, Sweden Supplement Nr 14 till Naring-

forskning, argang 20, 1976. Stockholm: Caslon Press.

Trowell H, Burkitt D and Heaton K (eds) (1985) Dietary

Fibre, Fibre-depleted Foods and Disease. London: Aca-

demic Press.

Vahouny GV and Kritchevsky D (eds) (1982) Dietary Fiber

in Health and Disease. New York: Plenum Press.

Vahouny GV and Kritchevsky D (eds) (1986) Dietary Fiber

Basic and Clinical Aspects. New York: Plenum Press.

Bran

A Zitterman, University of Bonn, Bonn, Germany

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Definition and Characteristics of Bran

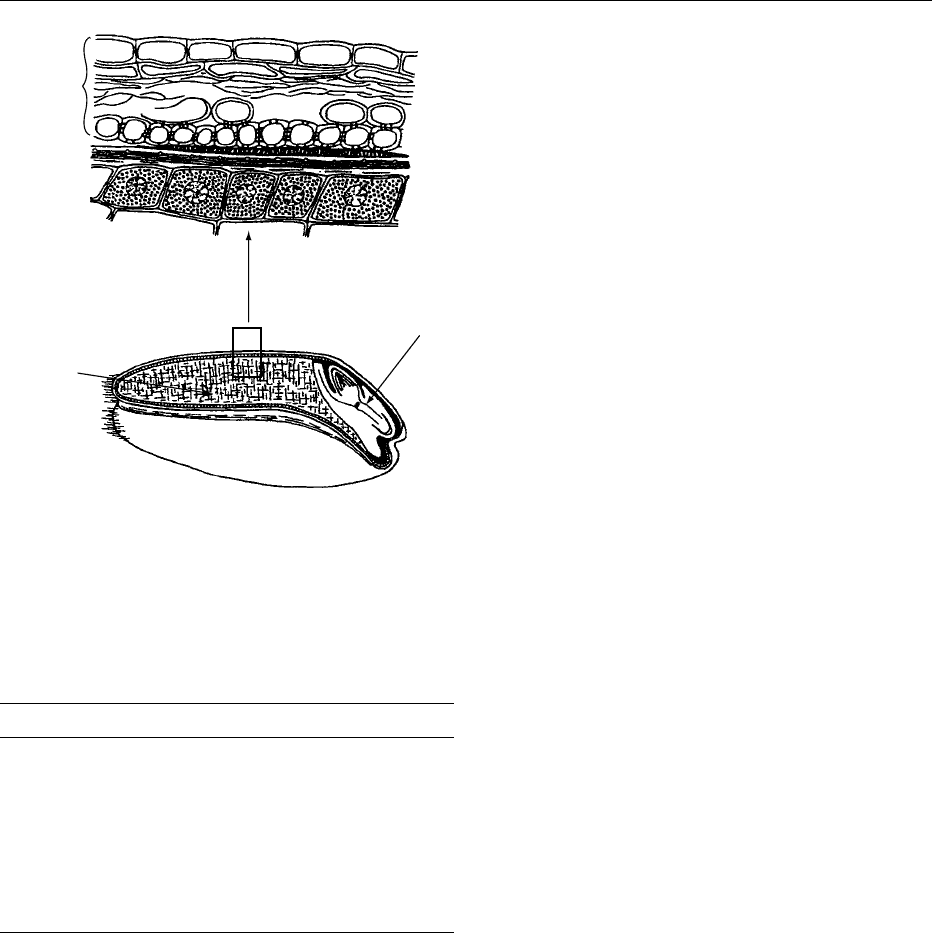

0001Bran is the outer coating or shell on grain that is

removed while processing white flour. Bran consists

of the pericarp, the seed coat, and the aleurone layer.

The pericarp itself consists of three layers of differen-

tiated types of cells (Figure 1). Wheat, oat, rice, and

rye are common sources of bran. The bran content of

wheat is approximately 15% of the whole grain. In

rice, where the beard is coalesced with the corn, the

bran content is only 8%. Typical commercial oat bran

products contain large amounts of adhering starchy

endosperm, because the endosperm tissues in the oat

grain do not separate cleanly and efficiently from the

outer layers. Bran has very little taste.

Chemical Composition of Bran

0002Bran is not a chemically defined substance. The com-

position of bran depends upon many different factors:

species and variety, e.g., grain, kernel seize, shape,

maturity, size of germ, and thickness of the outermost

layer, length of time and condition of grain storage,

system of grain conditioning before milling, the

milling system itself, and, above all, the type of flour

produced. The lower the extraction rate of the flour,

the more endosperm passes to the bran.

0003Bran is an excellent source of dietary fiber (Table 1).

However, it is important to recognize that bran is not

dietary fiber as such. Bran is also a good source of

tbl0006 Table 6 Effects of food constituents on postprandial

carbohydrate parameters

Product Blood

glucose

Insulin Glucagon

Partially hydrolyzed guar gum

(Sunfiber

1

)

##

Inulin and oligofructose ne ne ne

Polydextrose # ne

Galactooligosaccharides

Resistant maltodextrin

(Fibersol-2

1

)

###

ne, no effect; , no experimental evidence.

1844 DIETARY FIBER/Bran

certain nutrients. It is rich in protein, which is primar-

ily located in the aleurone layer. Rice bran is a par-

ticularly good source of fat (Table 1), mainly oleic

acid (40%), linoleic acid (34%), and palmitic acid

(17%). Moreover, approximately 70% of the mineral

content and between a third (thiamine) and two-

thirds (pyridoxine) of the B vitamins of cereal grains

are located in the bran fraction. Bran also contains

nonessential ingredients like phytic acid and ligans,

substances for which the effects on human physio-

logic functions have not yet been clearly established.

(See Fatty Acids: Properties; Vitamins: Overview.)

Dietary Fiber

0004 The high amount of insoluble dietary fiber in cereal

brans (Table 1) comes primarily from plant cell walls.

The cell walls consist of heterogeneous mixtures of

cellulose, noncellulose polysaccharides, and lignin

cross-linked to varying degrees to form a complex

matrix. Lignocellulose materials and insoluble

arabinoxylanes (hemicellulose) constitute most of

the mature cell wall of the plant materials such as

cereal brans. In addition, cell walls of the seed coat

contain cutin, a three-dimensional polyester, which

has similar properties to lignin. Moreover, ferulic

acid, the predominant phenolic acid in wheat bran,

is bound to the cell wall. (See Phenolic Compounds.)

0005Cereal brans can also contain varying amounts of

soluble arabinoxylanes and b-glucans, but no pectins.

b-Glucan is a soluble polysaccharide that is formed

exclusively by glucose residues. In contrast to the

insoluble cellulose, b-glucans are formed not only by

b-1,4 but also by b-1,3 glycosidic bonds. The ratio of

b-1,3 and b-1,4 glycosidic bonds is approximately

3:7. Normally, blocks of two to 10 b-1,4-glycosidic

glucose residues are interrupted by b-1,3-glycosidic

bonds. High amounts of b-glucans are found in the

aleurone layer and in the adhering endosperm of

some cereal brans. Similar to pectin, the physiologic

effects are related to the viscosity of b-glucans.

(See Carbohydrates: Classification and Properties.)

0006Like wheat bran (Table 1), barley bran contains up

to 55% of dietary fibers, of which normally 90% are

insoluble. Barley bran contains approximately 5% of

b-glucans. Special barley subspecies like ‘Prowasho-

nupana’ contain up to 15% b-glucans. The dietary

fiber content of rye bran is 28–36% and is thus lower

than that in wheat bran. However, the amount of

soluble arabinoxylanes in rye bran (15–25%) is rela-

tively high compared with wheat bran (1–1.5%). In

oat bran, the total amount of dietary fiber is 15–18%

with about 50–60% insoluble and 40–50% of soluble

dietary fibers. Oat bran normally contains 5–8%

b-glucans.

0007The rice bran produced under normal milling con-

ditions is unpalatable. When brown rice is milled to

white rice, the oil in the rice bran comes into contact

with a potent lipase also present in the bran, resulting

in rapid degradation of the oil to glycerol and free

fatty acids. However, if the bran is subject to a short-

term high-temperature heat treatment immediately

after milling, the lipase activity is destroyed, and

a stabilized bran is produced. In contrast to other

cereals, the rice grain has the ability to enrich sili-

cium. Therefore, the industry standard for rice bran is

a maximum of 0.1% silicium dioxide.

Phytic Acid

0008Phytic acid, the hexaphosphate of myo-inositol, is an

abundant component of bran, where it occurs as a

magnesium–calcium salt. The phytic acid content of

(a)

Pericarp

Seed coat

Aleurone

(b)

Starchy

endosperm

Embryo

(germ)

fig0001 Figure 1 (a) Longitudinal section of the bran layers of a wheat

grain showing the different cell types. (b) Longitudinal section

through a wheat grain: the rectangle indicates the location of the

section shown in (a). From Ferguson LR and Harris PF (1999)

Protection against cancer by wheat bran: role of dietary fibre and

phytochemicals. European Journal of Cancer Prevention 8: 17–25,

with permission.

tbl0001 Table 1 Chemical composition of wheat and rice bran

Grams per100 g dry weight Wheatbran Ricebran

Protein 13–18 12–20

Fat 3–6 3–22

Ash 6–7 9–13

Total dietary fiber 35–58 24–29

Soluble dietary fiber 2–5 2–4

Insoluble dietary fiber 32–53 20–24.5

Cellulose 6–12 6–12.8

Hemicellulose 19–31 8.7–17

Lignin 2–8 3–4

DIETARY FIBER/Bran 1845