Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

0023 Although most cases of dental caries originate with

dissolution of the enamel, the structure of the teeth is

such that should the gingival tissues or gums recede,

the neck of the tooth may be exposed. If this occurs,

dentine is quickly exposed, leading to sensitivity of

the tooth and, subsequently, dentinal or root caries.

As receding gingiva occurs with age, so root caries is

associated with the aging dentition and is seen mostly

in patients over 50 years of age.

Cementum

0024 The dentine of the root of the tooth is covered by a

thin layer of cementum. This structure, also of

mesenchymal origin, is again composed of inorganic

and organic material but is closer to bone in the

proportion of the two components. (See Bone.)

0025 Cementum provides a mean of bonding the teeth

into the bony sockets of the jaws by means of strands

of collagen, known as periodontal fibers. The whole

root is surrounded by many of these fibers, attaching

the tooth to the bone, and providing a system of

‘elastic bands,’ or a hydraulic system, so that the

tooth can be pressed deeper into its socket under biting

forces. This mechanism takes up heavy forces on the

tooth without them being transferred directly to the

bone, which would be very uncomfortable on biting.

0026 The cementum may break down as part of the dental

caries process or during gum disease, or be worn away

by excessively hard tooth brushing. Because of its

lower inorganic content, its resistance to decay or

wear is far less than either enamel or dentine, and if

exposed, it can wear away quite quickly.

See also: Bone; Calcium: Physiology

Further Reading

Nikiforuk G (1985) Understanding Dental Caries: 1.

Etiology and Mechanisms. Basic and Clinical Aspects.

Basel: Karger.

Thylstrup A and Fejerskov O (1986) Textbook of Cariol-

ogy, 1st edn. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

Etiology of Dental Caries

M S Duggal and M E J Curson, University of Leeds,

Leeds, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Introduction

0001 Dental caries or tooth decay is a pathological process

of localized destruction of tooth tissues. It is a form of

progressive loss of enamel, dentine, and cementum

initiated by microbial activity at the tooth surface.

Loss of tooth substances is preceded by a partial

dissolution of mineral ahead of the total destruction

of the tissue. It is because of this characteristic that

dental caries can be differentiated from other destruc-

tive processes of the teeth, such as abrasion through

mechanical wear and erosion by acid fluids.

Current Concepts of Caries Etiology

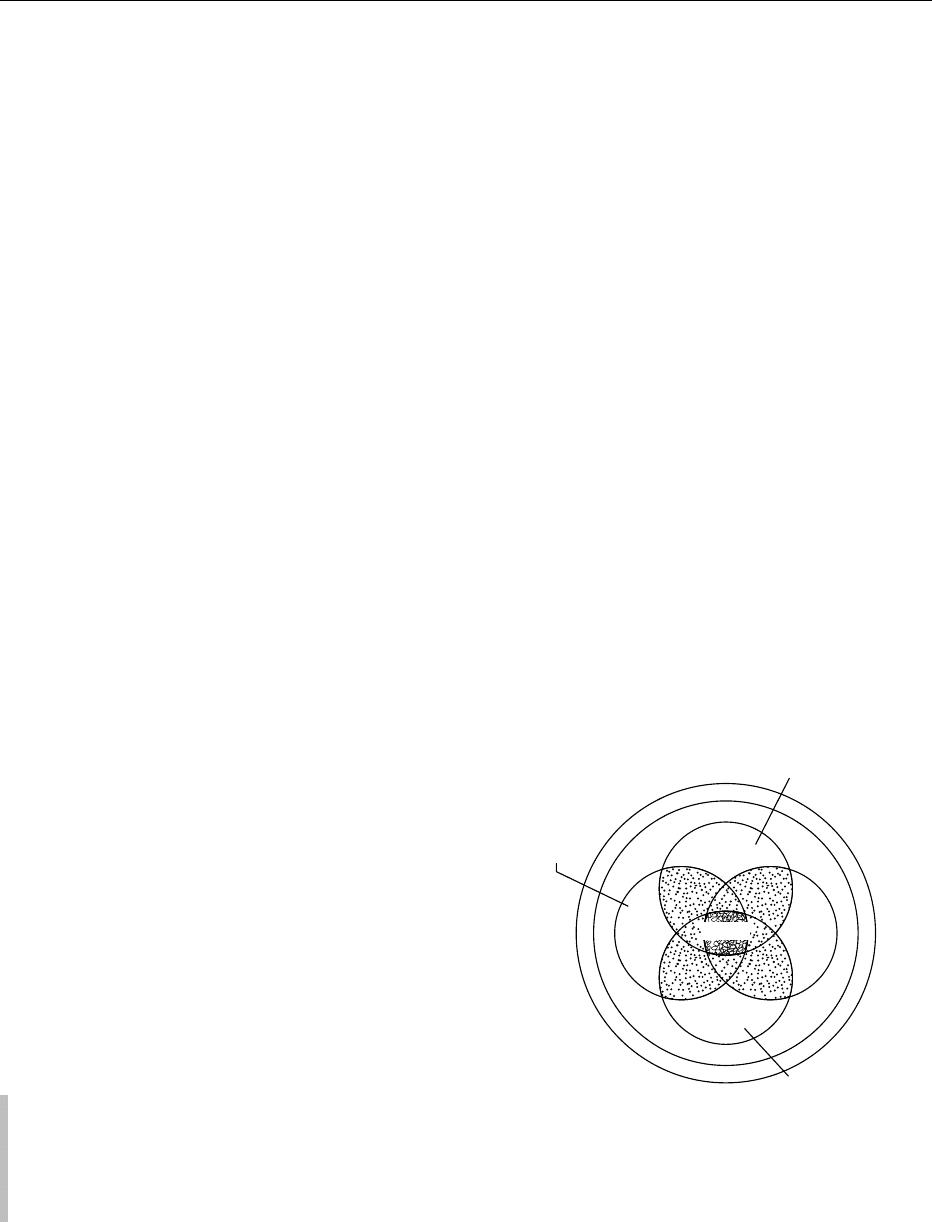

0002There is overwhelming evidence that the initial phase

of dental caries involves demineralization of the tooth

enamel by localized high concentrations of organic

acids. These acids are produced by the fermentation

of common dietary carbohydrates by bacteria that

accumulate in dental plaque on the teeth. This con-

cept of dental caries etiology is based essentially on

the interplay of four principal factors: a susceptible

host (the tooth), microflora with an acidogenic

potential, a suitable substrate available locally to the

pathodontic bacteria (carbohydrate), and a fourth

important dimension, time (Figure 1). Because of the

multiplicity of factors which influence the initiation

and progression of dental caries it is often referred to

B

u

f

f

e

r

i

n

g

c

a

p

a

c

i

t

y

p

H

c

o

m

p

o

s

i

t

i

o

n

F

l

o

w

r

a

t

e

p

H

Tooth

Tooth

Time

Saliva

Saliva

Saliva

Saliva

Age

Fluorides

Morphology

Nutrition

Trace elements

Carbonate level

Substrate

Substrate

Micro-

organisms

Oral clearance

Oral hygiene

Detergency of food

Frequency of eating

Carbohydrate (type,

concentration)

Microorganisms

(Substrate)

Oral hygiene

Fluoride in plaque

Streptococcus mutans

Caries

fig0001Figure 1 Diagrammatic representation of the parameters in-

volved in the carious process. All factors must be acting concur-

rently for caries to develop. Dental Disease/Aetiology of Dental

Caries, Reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food

Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ

(eds), 1993, Academic Press.

1746 DENTAL DISEASE/Etiology of Dental Caries

as a disease of a ‘multifactorial etiology’, an old but

appropriate description. In this article the role of

microflora and the host susceptibility are discussed.

The role of carbohydrates in the diet is discussed

later. (See Carbohydrates: Digestion, Absorption, and

Metabolism; Requirements and Dietary Importance.)

The Role of Microorganisms

0003 Considerable difference of opinion exists within the

dental research community as to which microorgan-

isms cause dental caries and whether indeed a specific

strain of bacteria is responsible in its causation. How-

ever, there is evidence that microorganisms, which

accumulate in dental masses (dental plaque) on the

teeth, cause fermentation of dietary carbohydrates,

producing organic acids which cause demineraliza-

tion of the tooth enamel. This concept is a combin-

ation of Miller’s acidogenic theory of 1889 and that

of dental plaque introduced by Williams in 1897.

Subsequent research has supported this original view

and the evidence implicating oral microorganisms in

the etiology of dental caries is summarized below:

1.

0004 Germfree animals do not develop dental caries.

2.

0005 Addition of penicillin to the diet of rats prevents

caries.

3.

0006 Plaque bacteria can demineralize enamel in vitro

when incubated with dietary carbohydrates.

4.

0007 Microorganisms can be found invading carious

enamel and dentine.

5.

0008 Animals in which diet or dietary carbohydrates are

delivered directly into the stomach through a tube

do not develop caries.

Role of Dental Plaque

0009 Dental plaque is the name given to the aggregations of

bacteria and their products which accumulate on the

tooth surface. Plaque collects rapidly in the mouth,

although the actual rate of formation varies from one

individual to another. When plaque accumulates on the

crowns of teeth the natural, smooth, shiny appearance

of the enamel is lost and a dull, matt effect is produced.

As it builds up, masses of plaque become more readily

visible to the naked eye. In direct smears, the early

plaque is dominated by cocci and rods, most of which

are Gram-positive. In the mature plaque (after about 7

days) the percentage of cocci in the plaque decreases

rapidly and filaments and rods constitute about 50% of

organisms in plaque. The ecological term for this shift

from a predominantly coccal type in the beginning to a

predominantly mixed, filamentous flora a few days

later is bacterial succession.

0010 There is no doubt that the presence of plaque is

required for caries development in humans. The best

available evidence suggests that a carious lesion results

from the action of bacterial metabolic end products

localized to the enamel surface by dental plaque. It is

therefore the acidity generated by the microorganisms

in the plaque after exposure to carbohydrates that is

directly responsible for causing demineralization. This

is under the influence of many factors.

Regulators of Plaque Acidity

0011Various parameters have been studied for their effect

on plaque acidity, and hence their effect on caries;

these are listed in Table 1. The role of saliva will be

discussed later, and carbohydrates as regulators of

plaque pH are discussed elsewhere.

0012Bacterial mass in relation to caries Plaque is re-

quired for caries initiation, although the relationship

between the plaque quantity and dental caries activity

is unclear. Some earlier studies, using a crude method-

ology, showed a positive correlation between caries

increment and oral hygiene, but more controlled

investigations failed to establish this finding. Many

individuals remain caries-free in spite of an unfavor-

able oral hygiene. This lack of a clear-cut relationship

between amount of plaque and dental caries suggests

that plaques vary in their microbial composition and,

although present in equal amounts, might vary in

their cariogenicity. Impressive evidence indicates

that the qualitative nature of the plaque flora deter-

mines the metabolism and the potential for caries

production. This view has been referred to in the

literature as the specific plaque hypothesis.

0013Bacterial composition of plaque and caries Most

published data on gnotobiotic animals have concen-

trated on the cariogenic potential of streptococci,

especially Streptococcus mutans.However,several

organisms have been found capable of inducing

carious lesions when used as monocontaminants in

gnotobiotic rats. These include S. mutans, S. salivarius,

S. sanguis, S. milleri, Lactobacillus acidophilus,

Peptostreptococcus intermedius, Actinomyces visco-

sus,andA. naeslundii. However, not all organisms are

equally cariogenic. Table 2 shows the acidogenicity and

tbl0001Table 1 Factors influencing pH of dental plaque

Carbohydrates Saliva Plaque

Quantity of intake Flow rate Bacterial mass

Frequency of intake Buffer capacity Bacterial composition

Retentiveness Other factors,

e.g., urea,

ammonia

Acid production

Modifying effects

of other ingredients

of foodstuffs

Acid tolerance

Acid retention

DENTAL DISEASE/Etiology of Dental Caries 1747

acid tolerance of plaque bacteria. In evaluating data

shown in Table 2 it should be noted that the final pH

represents the pH observed after incubation of pure

bacterial cultures in broth with excess carbohydrates.

Table 2 also indicates the tolerance of bacterial systems

of plaque to acid. Though these data do not reveal the

rate at which acid is produced or the pH at which

growth ceases, they give some insight into the relative

acidogenic, i.e. cariogenic, potential of plaque bacteria.

Bacterial Specificity and Dental Caries

0014 Investigations into the relationship between various

plaque organisms and dental caries have mainly

focused on streptococci, lactobacilli, and filamentous

bacteria.

Streptococci

0015 Studies of S. mutans strongly suggest its active in-

volvement in the initiation and progression of dental

caries. Members of this species are nonmotile, cata-

lase-negative, Gram-positive cocci. On Mitis salivar-

ius agar they grow as highly convex colonies. When

cultured with sucrose they form polysaccharides

which are insoluble. This property of forming insol-

uble polysaccharides from sucrose is regarded as an

important characteristic contributing to the caries-

inducing properties of the species. S. mutans can

invariably be isolated from incipient lesions as well

as lesions that have cavitated on pits and fissures,

approximal and smooth surfaces. It can also be isol-

ated with highest frequency from plaque over carious

lesions, and the isolation frequency decreases when

the samples are taken further away from the lesions.

0016 S. sanguis is also one of the predominant groups

of streptococci which colonize the tooth surface.

Evidence suggests that caries from this strain is

significantly less extensive than that from S. mutans

and occurs primarily in pits and fissures, whereas

S. mutans causes smooth surface caries as well.

0017It would therefore appear that S. mutans is the

most cariogenic of the family of streptococci. Its car-

iogenicity is attributed to several important proper-

ties:

1.

0018It synthesizes insoluble polysaccharides from

sucrose.

2.

0019It colonizes all tooth surfaces.

3.

0020It is a homofermentative producer of lactic acid.

4.

0021It is more acidogenic than other streptococci.

Lactobacilli

0022Lactobacilli have also been implicated in the etiology

of dental caries for many decades. Although a few

studies have suggested their involvement in the initi-

ation of caries, they are most often found in large

numbers in carious cavities. This and the fact that

lactobacilli have a relatively low affinity for the

tooth surface suggest that they might have a more

important role to play in the progression rather than

initiation of dental caries.

Filamentous Bacteria

0023Filamentous bacteria, especially actinomycetes, have

been found to be associated with root surface caries.

Actinomyces viscosus, an acidogenic bacterium, is

almost always isolated from plaques overlying root

lesions. The role of A. viscosus in the initiation of root

lesions is difficult to assess because they are often

predominant on the sound root surfaces in subjects

experiencing and resisting root caries. More definitive

studies are needed to determine the association of

A. viscosus and root caries.

0024It must be remembered that most of the micro-

organisms implicated in dental caries etiology are

indigenous organisms and exist in a dynamic relation-

ship with the host. Disease is not a necessary outcome

of this association but it may ensue when the balance

is greatly disturbed. With S. mutans this may occur,

for example, when its numbers on teeth are increased

owing to a higher or more frequent consumption of

carbohydrates.

The Host Factors

Saliva

0025Saliva significantly influences the carious process.

For example, removal of the salivary glands of

hamsters greatly enhanced the caries activity when

they were fed a high-sucrose diet. Human studies

have demonstrated the same results and have shown

that if the exposure of teeth to saliva is restricted by

blocking the opening of the salivary glands the pH

values of plaque, after exposure to carbohydrates, are

lower.

tbl0002 Table 2 Acidogenicity and acid tolerance of some plaque

bacteria

pH Initiationof growth

< 4.0 4.1^4.5 4.6^5.0 > 5.0

Streptococcus

mutans

þþ 5.2

S. sanguis þþ 5.2–5.6

S. salivarius þþ 5.2

S. mitis þþ 5.2–5.6

Lactobacillus þþ <5.0

Actinomyces þþ?

Enterococci þþþ?

Adapted from Van Houte J (1980) Bacterial specificity in the etiology of

dental caries. International Dental Journal 30: 305–325.

1748 DENTAL DISEASE/Etiology of Dental Caries

0026 Salivary flow and caries rate Humans suffering

from xerostomia or decreased secretion of saliva as

a consequence of a pathological condition such as

sarcoidosis, Sjo

¨

gren’s syndrome, etc., often experi-

ence a higher rate of caries. The tooth destruction as

a result of desalivation is typically quite rapid. Ram-

pant caries has been demonstrated in patients who

have been treated by radiotherapy to the head and

neck as irradiation of the salivary glands leads to

decreased salivary flow and usually leads to extensive

caries in the cervical region of the teeth. These obser-

vations have led to the conclusion that saliva is in

some way important to maintain the integrity of the

tooth substance.

0027 Salivary buffering and dental caries Saliva contains

bicarbonate-carbonic acid and phosphate buffer

systems. The buffering capacity acquired by saliva

by virtue of these ion systems tends to correct pH

changes caused by concentration changes of acidic

ions produced by fermentation of carbohydrates. A

typical reaction of plaque to carbohydrate challenge

is an immediate drop in plaque pH followed by a

gradual rise to the resting value. However, if plaque

and teeth are isolated from the influence of saliva the

pH of plaque drops further and remains low for

prolonged periods. Thus the buffering capacity of

saliva is an important factor in reducing the time the

tooth enamel is exposed to the acidogenic challenge.

0028 Other protective factors in saliva Saliva contains a

number of factors of glandular origin, including

lysozymes and a peroxidase system. Interest has also

been focused on the immunological aspect of caries,

and specific immunoglobulin A (IgA) antibodies to

S. mutans have been detected in saliva by immune

assays. The concentration of secretory IgA in whole

saliva has been reported to be significantly less in

subjects with a high caries rate as compared with

those with a lower caries experience. Although sub-

stantial evidence suggests that the aforementioned

factors form an antibacterial system in saliva, the

extent to which they contribute to caries resistance

of the host is not yet clear.

Tooth

0029 Tooth morphology and dental caries A susceptible

host is one of the factors which is required for caries

to occur. The morphology of the tooth has long been

known to be one of the major determinants of its

susceptibility. Clinical observations have suggested

that pits and fissures of posterior teeth are highly

susceptible to caries. This is thought to result from

impaction of food and microorganisms in the fissures

which are also difficult to reach with routine oral

hygiene aids. An interesting observation is that there

is a positive correlation between the depth of the

fissures and caries susceptibility.

0030It has also been observed that certain surfaces of a

tooth are more prone to caries than other surfaces. For

example, the occlusal surface and the buccal surface of

the lower first permanent molar are more likely to

develop caries as compared with the lingual, mesial,

or distal surfaces, probably because of the presence of

the fissures on the occlusal surfaces and the buccal pit

on the buccal surface. Similarly, an intraoral variation

in susceptibility to caries exists between different

teeth. The caries susceptibility by tooth type, in des-

cending order, is as follows: first permanent molar,

second permanent molar, second premolar, upper in-

cisor, first premolar, with the lower incisors and

canines least likely to develop caries.

0031Arch morphology and caries Irregularities in the

arch form and imbrication of the teeth also favor

the development of caries. It has been shown experi-

mentally that enamel in stagnation areas is more

likely to develop demineralization, which is mani-

fested as white spot lesions.

0032Tooth composition and dental caries It is well

known that the surface enamel is more resistant to

caries attack than the subsurface. This is attributed

to a higher concentration of fluoride and other

trace metals, such as zinc and lead, which are thought

to protect the surface enamel from demineraliza-

tion. It is because of this that dental caries is often

said to be subsurface in origin. Although there is

plenty of evidence to support the direct relationship

between the fluoride content of the surface layer of

enamel and its resistance to caries attack, the relation-

ship of other trace elements is unclear and still being

investigated.

See also: Carbohydrates: Digestion, Absorption, and

Metabolism; Requirements and Dietary Importance;

Immunology of Food

Further Reading

Newbrun E (1979) Cariology, 2nd edn. Baltimore: Williams

and Wilkins.

Silverstone LM, Johnson NW, Hardie JM and Williams

RAD (1981) Dental Caries – Aetiology, Pathology and

Prevention. London: Macmillan.

Thylstrup A and Fejerskov O (1986) Textbook of Cariol-

ogy, 1st edn. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

Van Houte J (1980) Bacterial specificity in the etiology of

dental caries. International Dental Journal 30: 305–325.

DENTAL DISEASE/Etiology of Dental Caries 1749

Role of Diet

M S Duggal and M E J Curson, University of Leeds,

Leeds, UK

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Introduction

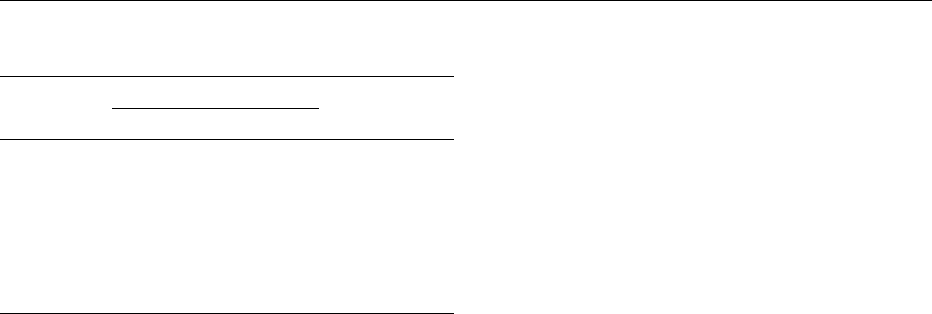

0001 The driving force for the development of preventive

dentistry and its effective use in patient management

has been the expanding understanding of the disease

of dental caries itself. As already discussed, dental

caries is now recognized as a disease of altered ecology

in which the host, oral microflora, and diet interact to

present a challenge too strong for the normal defense

mechanisms. It is wrong, however, to regard caries as a

simple, continuing acid demineralization of the tooth

enamel. Although teeth may be frequently exposed to

acid environment, caries does not always arise as it is a

result of a dynamic interaction of demineralization

and remineralization. These are under the influence

of a whole range of both cariogenic and protective

factors (Figure 1). It is clear from this model that diet

forms a part of a large spectrum of etiological factors

involved in the caries process. Sugar and other fer-

mentable carbohydrates in the diet constitute an es-

sential aspect of cariogenic potential of food, with

other factors, such as the frequency of intake, reten-

tiveness, and buffering potential of foods, also playing

an important part. These are in addition to the tooth

structure, saliva flow and composition, and the pres-

ence of oral bacteria. This article is concerned with the

discussion of the dietary considerations related to the

etiology of dental caries.

The Role of Diet in the Etiology of Dental

Caries

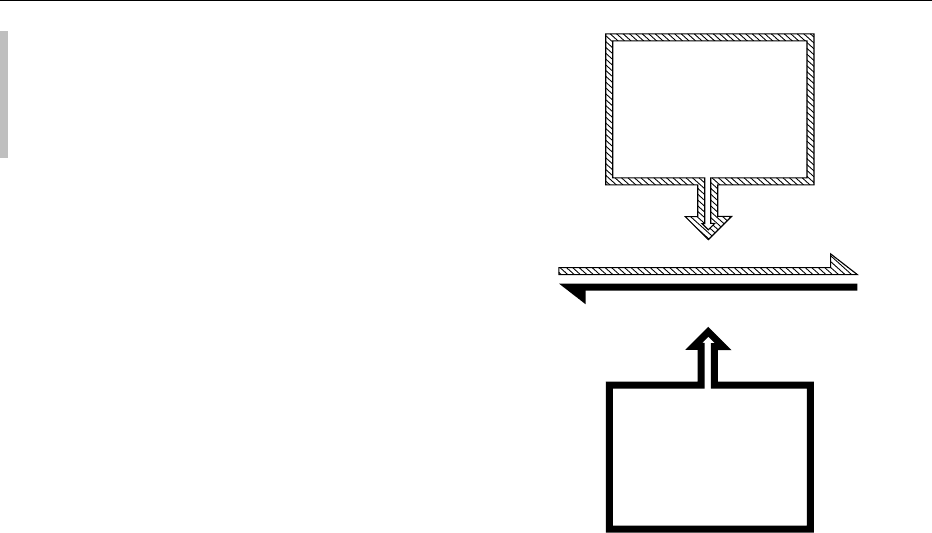

0002 Epidemiological studies have been used to try to

establish the relationship of various types of diets

and dietary components to caries incidence. Circum-

stantial evidence linking sucrose consumption and

prevalence of dental caries can be readily found in

several epidemiological surveys. For example, the

prevalence of caries among the native population of

Tristan da Cunha, and among Eskimos and Austra-

lian Aborigines, was low before western-type food

was introduced into their diets. Controlled human

studies, mostly on institutionalized subjects, also in-

dicated that sucrose-containing diets were cariogenic.

0003 It is well known that when eating foods containing

fermentable carbohydrates the pH of plaque drops,

implying localized generation of acid. The drop in pH

is the result of fermentation carbohydrates by the

plaque bacteria, producing lactic and other organic

acids, and is followed by a gradual return to the

resting or near-resting pH. This recovery depends on

a number of factors, including the buffering potential

of plaque and the food, retention, or the rapidity of

clearance from the mouth. The whole cycle of pH

drop and recovery was first described by Stephan in

1940 and is commonly known as the Stephan curve

(Figure 2). (See Carbohydrates: Digestion, Absorp-

tion, and Metabolism; Requirements and Dietary

Importance.)

0004It is agreed that foods which produce a pH drop

below pH 5.5, known as critical pH, are considered

detrimental to teeth. The pH value 5.5 is considered

critical because it is thought that enamel demineraliza-

tion occurs below this point. Some authors regard

values below 5.7 as being cariogenic. Foods giving a

pH drop between 5.5 and 6.0 are also dubious. This

form of ranking is referred to as relative potential car-

iogenicity. Of greater importance is the relative cario-

genic potential of foods compared with known foods of

high cariogenicity (sucrose) and low cariogenicity

(sorbitol), as agreed at the international conference on

cariogenicity of foods at San Antonio in 1985.

0005In one study, using the plaque-harvesting method, a

representative sample of plaque was removed from

human mouths before and after consumption of

foods, and the pH response of that plaque was

Total cariogenic load

Frequency

Cariostatic factors

Buffering

Sound

enamel

Dental

caries

Demineralization

Remineralization

Carbohydrates

Retention/clearance

Total protective factors

Fluorides

Fissure sealants

Oral hygiene

Salivary components

Host susceptibility

fig0001Figure 1 A dynamic model of caries. Reproduced from Dental

Disease/Role of Diet, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Tech-

nology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ

(eds), 1993, Academic Press.

1750 DENTAL DISEASE/Role of Diet

assessed. The response followed a typical Stephan

curve and the potential acidogenicity of the foods

was compared by measuring the minimum pH

recorded and the area enclosed by the curve under

the resting pH value. Acidogenicity in a range of

snack foods is assessed in Table 1. Interestingly,

some foods which are perceived to be ‘better for

teeth’ actually fare quite badly in such a ranking,

compared with foods traditionally thought of as

‘bad for teeth,’ such as chocolate.

0006This study bore out a previous study demonstrating

that ingestion of chocolate or even apples resulted in a

similar pH response. Later work, using the same test

procedure, also showed that a wide range of foods

containing either sugar or starches, or combinations

thereof, are potentially acidogenic and thus possibly

cariogenic.

0007It is important to note that the concentration of

fermentable carbohydrate in a food does not affect

the pH drop in the mouth, although the period of

time taken to return to normal pH levels may be related

to concentration. This return to resting pH is as much

related to the buffering capacity of the saliva or plaque,

buffering capacity of the foods, and the physical prop-

erties of the food itself. The retentiveness, and hence

clearance rate, of a food is therefore an important

determinant of the cariogenic potential of that food.

The concentration of a single ingredient of a food has

little relation to the cariogenicity; it is the ability of the

whole food to promote caries that is important.

Tests for Cariogenicity of Foods

0008Animal experiments have been used to rank different

foods in the order of their cariogenicity. In one such

study a selection of human snack foods was ranked

by their cariogenic potential index (CPI) by feeding

5

0

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

10 15 20

Time

Critical pH

Safe

pH

Doubtful

Demineralization

25 30 35 40

fig0002 Figure 2 A typical Stephan’s curve. Reproduced from Dental

Disease/Role of Diet, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Tech-

nology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler MJ

(eds), 1993, Academic Press.

tbl0001 Table 1 Acidogenic potential of carious snack foods (US) grouped by category and acidogenicity

Group Beverages Fruit, etc. Baked goods Sweets

Least acidogenic Milk Peanuts

Chocolate milk Potato chips (crisps) Bread and butter

Apple Graham crackers Caramels

Sugared gum

Chocolate

Licorice

Sugarless gum

Carbonated beverages Banana Cream-filled cakes

Sandwich cookies Orange jellies

Apple juice Dates Doughnut

Raisins Bread and jam

Orange juice Sweetened cereal Whole-wheat bread

Plain sweet biscuits/cakes

Apple pie Rock candy

Chocolate Clear mints

Graham

Angel food cake

Most acidogenic Sourballs

Fruit gums

Fruit

Lollipops

After Edgar WM (1981) Plaque pH assessments related to food cariogenicity. In: Hefferen JJ (ed.) Foods, Nutrition and Dental Health, vol. 1, pp. 137–150.

Illinois: Pathotox.

DENTAL DISEASE/Role of Diet 1751

laboratory rats via a gastric tube, thus bypassing the

mouth. Sucrose was used as a reference food and

given a CPI of 1.0. Foods with a score of less than

1.0 were considered less cariogenic than sucrose,

while those with a score above 1.0 were thought to

be more cariogenic. Interestingly, the concentration

of sucrose in a breakfast cereal made little or no

difference to the CPI. The results, given in Table 2,

show that potato chips (crisps) actually score higher

than chocolate bars. It is clear from most of these

experiments that any foodstuff containing carbohy-

drate has the potential to cause significant amounts of

acid to be produced at certain sites in the dentition,

which can be followed by demineralization of the

enamel and subsequent caries. However, it must

be remembered that not all occasions of a drop in

plaque pH are accompanied by demineralization of

the enamel. This has prompted many investigators

to question the significance of acid production as a

measure of the cariogenicity of the foods. It has also

been shown that the total amount of titratable acid

produced by the foods does not necessarily parallel

the amount of enamel it will dissolve. It is now well

accepted that the cariogenic potential of a food is

influenced by a number of other factors, including

the ability of the foods to remain in the oral cavity

and, in some cases, the sequence of food intake. Thus,

studies on the relationship between food and dental

caries should consider not only foods in themselves

but also their relationship to other items of diet with

regard to their nature, timing, and order of usage.

Cariostatic Factors in Food

0009 Some components of foods may be cariostatic. Pro-

teins may assist remineralization of enamel or reduce

the rate of crystal dissolution. Some fatty acids have

been shown to reduce caries in rat studies while phos-

phates have been shown to have a marked protective

effect. Inorganic phosphates have been demonstrated

to have a protective influence when added to a

cariogenic diet. Organic phosphates such as phytates

and glycerophosphates also have a cariostatic action

and are thought to reduce the cariogenicity of diets.

Although the exact mechanism of action is unknown,

studies have indicated that it might be a local modify-

ing influence in the oral cavity, rather than a systemic

effect through ingestion. The local effects of phos-

phates can be attributed to various properties:

1.

0010Phosphates are good buffers; thus they can buffer

organic acids produced by plaque flora.

2.

0011Phosphates are known to reduce the rate of dissol-

ution of hydroxyapatite.

3.

0012Phosphates can desorb proteins from the enamel

surface; thus they can possibly have a modifying

influence on acquired pellicle.

The protection afforded by fluoride is well docu-

mented and has led some researchers to refer to dental

caries as a fluoride-deficiency disease. These mater-

ials are all components of various foods. Further-

more, some cariostatic agents have been isolated

from cereals and cocoa and these factors may all

influence the level of caries caused. Accordingly the

level of fermentable carbohydrate in a food will not

be directly related to the degree of caries caused.

Food Retention

0013Tests have illustrated that, contrary to popular opin-

ion, foods that are perceived to be ‘sticky,’ such as

caramel, tend to clear from the oral cavity faster than

many other foods considered cariogenic. As Table 3

shows, after 15 min, white bread was retained in

higher quantities in the oral cavity than cake,

chocolate, or hard mint. After 30 min, there was

more residue from raisins than from caramel. Raisins

have been consistently shown to be highly cariogenic.

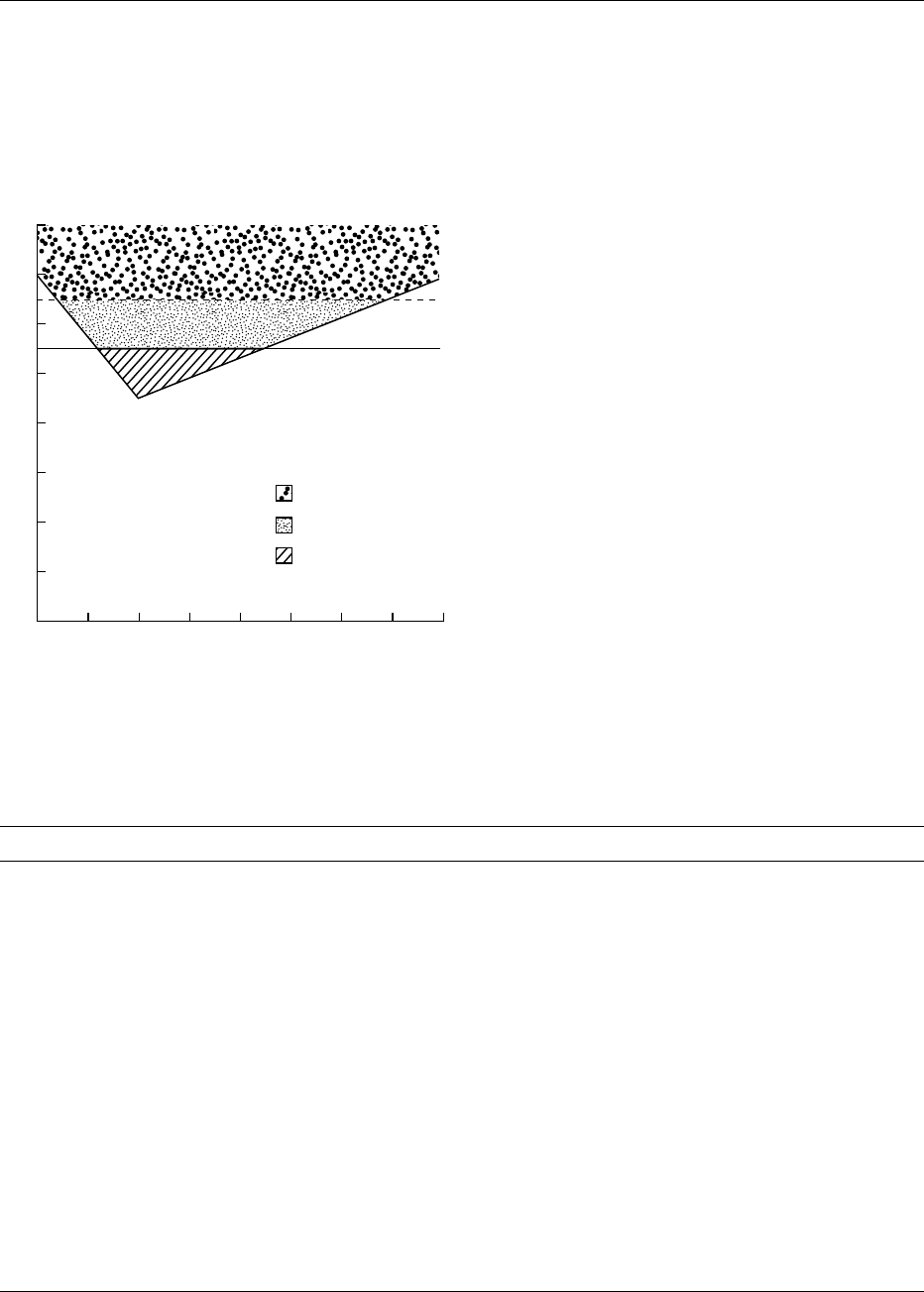

0014Beverages, which are perceived to clear quickly

from the mouth, actually sustain a low pH level for

the same period as a ‘sticky’ confectionery. In a recent

study a range of fruit drinks which were advertised as

‘sugar-free’ or as ‘no added sugar’ were assessed on

the basis of their ability to reduce the pH of plaque. It

was found that the fact that most of these drinks had

little natural sugar (sucrose) did not affect their ability

to reduce the pH of plaque; when compared with a

standard 10% sucrose rinse they were equally acido-

genic. This was attributed to the presence of natural

sugars – fructose and glucose – in these drinks. These

so-called natural sugars are also fermentable by oral

tbl0002 Table 2 Selected rankings of cariogenic potential index (CPI)

in rats using human food as snacks

Food tested CPI

Sucrose 1.0

Filled chocolate cookie 1.4

Cereal (14% sucrose) 1.1

Cereal (8% sucrose) 1.0

Cereal (60% sucrose) 0.9

Coated chocolate candy 0.9

Potato chips 0.8

Caramel 0.7

Chocolate bar 0.7

Cereal (2% sucrose) 0.5

Starch 0.5

Sucrose plus 5% Dical 0.4

No meals by mouth 0.0

After Bowen WH, Amsbaugh SM, Monnel-Torrens S et al. (1980) A method

to assess cariogenic potential of foodstuffs. Journal of the American Dental

Association 100: 677–681.

1752 DENTAL DISEASE/Role of Diet

bacteria and their presence instead of sucrose does

not render the drinks any safer for teeth. In fact,

when the fruit drinks were compared with 10%

sucrose it was obvious that the pH recovery was

slower after consumption of fruit drinks and the pH

remained below 5.5 for a longer time (Figure 3). This

is because of an inherent buffering potential of fruit

drinks which gives them an ability to resist any

attempts by saliva to buffer the acid. These drinks

can therefore be deemed to be more cariogenic

than a pure 10% sucrose solution. This research

highlighted the fact that the concentration of sugars

alone is not the sole determinant of the acidogenicity,

and hence cariogenicity, and other factors discussed

above are equally important. (See Carbohydrates:

Metabolism of Sugars.)

Eating Pattern and Frequency

0015On a population level, the average amount of sucrose

consumed per capita relates to the average level of

caries in the population. However, more detailed

studies show the relationship to be less consistent

and of low statistical significance. In the classical

study often referred to as the Vipeholm study, inmates

of a Swedish Medical Institute were fed increased

sucrose or other foods in different patterns and caries

experience was monitored. Groups of patients receiv-

ing high levels of sucrose (up to 330 g day

1

) with

their meals experienced minimal increase in caries.

But if smaller quantities of sucrose were consumed

between meals, very high levels of caries ensued. The

relationship was not therefore between quantity of

sucrose and caries but rather frequency of intake

and caries experience. This relationship, which has

been confirmed in human and animal research, sheds

light on why population studies do not demonstrate

a clear and consistent relationship between sugar

consumption and caries. For example, long-term

diet–caries studies carried out in the UK showed

that statistical correlation of sugar concentration to

caries was 0.16 and explained only 4% of the caries

variance.

0016Experience from primitive and developing cultures

with little access to sucrose but abundant access to

starch is often cited as evidence that sucrose and not

starch results in dental caries. This evidence purports

to be strengthened by the fact that introduction of

western diet (including sucrose) immediately results

in development of dental caries. It can be argued that

introduction of a western diet is accompanied by

increased affluence and an altered eating pattern.

Such changes also include differences in the use

of cooked starches as much as differences in use of

sucrose. Frequency of intake of any food increases

dramatically, along with the potential incidence of

dental caries. It is also interesting to note that caries

has been shown to be associated with a diet consisting

of sago starch, as in the Sepik villages in Papua New

Guinea.

Sugars and their Role in Caries

0017In western society, eating frequency has generally

increased and snacking has become an accepted

aspect of life. This change took place over a long

period of the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries

12

11

10

9

8

7

6

5

4

3

2

1

0

Apple/chR

Apple/chD

Apple/bcCG

Apple orange D

Ribena app/bcB

Ribena orange B

Sucrose

Time (min)

Gripe water W

Summer fruits CG

Pear/peach CG

Apple/bcD

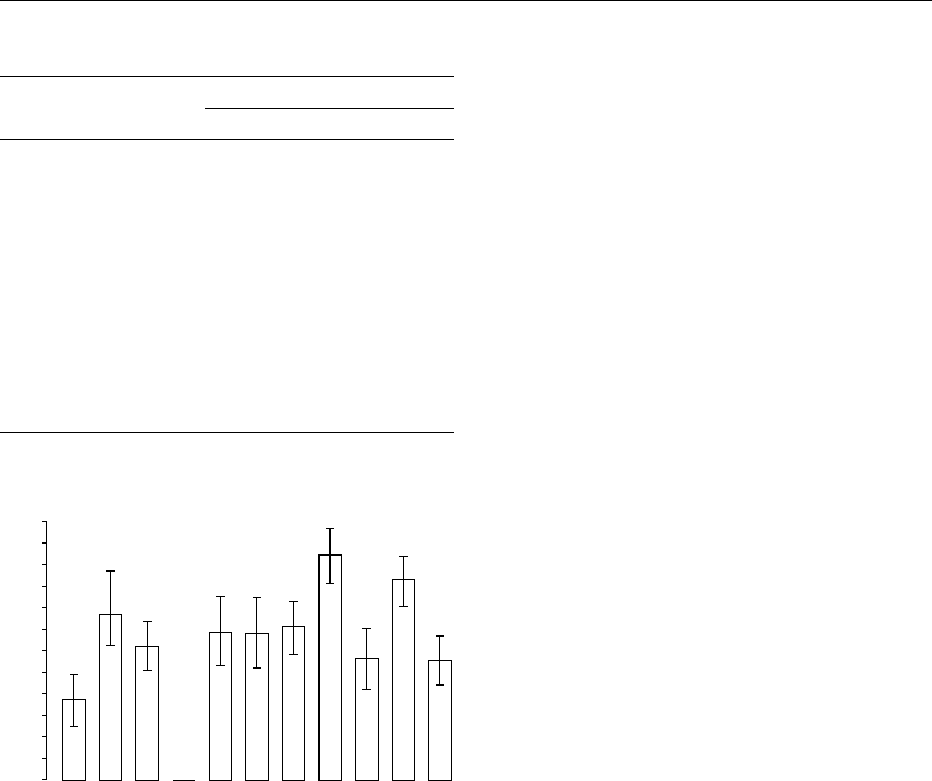

fig0003 Figure 3 Bar graph showing mean time spent below pH 5.5 for

fruit drinks compared with a 10% sucrose rinse. Reproduced

from Dental Disease/Role of Diet, Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler

MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

tbl0003 Table 3 Representative figures (mg) for food retention in

mouth after eating

Food Food retention (mg) after

5 min 15 min 30 min

Peanuts 4.9 3.3 2.6

Dentyne gum 5.0 3.9 3.1

7-Up 6.3 2.4 2.1

Chocolate milk 7.4 3.8 1.9

Potato chip 12.3 4.9 2.5

White bread 16.1 10.0 3.6

Raisins 16.8 5.7 3.0

Sponge cake 18.8 6.0 4.2

Caramel 19.0 4.2 2.5

Milk chocolate 19.0 6.8 3.0

Cracker (oil-sprayed) 23.8 8.5 3.7

Hard mint 31.9 9.4 2.5

Cracker (plain) 33.6 10.4 3.3

Sandwich cookie 35.0 8.4 4.9

After Bibby BG (1981) Foods and dental caries. In: Hefferren J (ed.) Foods,

Nutrition and Dental Health, vol. 1, pp. 257–278. Illinois: Pathotox.

DENTAL DISEASE/Role of Diet 1753

when the incidence of dental caries increased. How-

ever, in the past 20 years, while sucrose usage has not

changed, dental caries has dramatically decreased. In

the case of 5-year-olds, the percentage with tooth

decay fell from 73% in 1973 to 48% in 1983.

0018 Reducing the frequency of eating just one of these

foods, or reducing the concentration of sugars in a

food, is unlikely to have a significant effect on the

incidence of caries as nearly all foods contain some

fermentable carbohydrate. It has been assumed tacitly

both by practicing dentists and by too many dental

investigators that the cariogenicity of an individual

food is directly proportional to its content of sucrose

or other fermentable carbohydrates. There are no

quantitative data to support this belief. The effects

of high sucrose concentrations in increasing the rate

of food clearance of some foods from the mouth and

in inhibiting the fermentation process make it seem

improbable that high sugar content of itself would be

particularly damaging to teeth. The Vipeholm study

has been mentioned as evidence for the cariogenicity

of sucrose, although investigators have questioned

the reliability of a single clinical study from a mental

institute. There are a number of contradictory studies

that have not been widely recognized. For example,

one group of investigators, studying English children,

found that they could substantially increase sugar as

sucrose in the children’s diet without increasing the

incidence of caries.

0019 It is the frequency of consumption rather than the

amount consumed which is associated positively with

dental caries incidence. Considering the already

substantial decline in the incidence of dental caries

in the west, where frequency of eating has generally

increased, and given the fact that dietary manipula-

tion is difficult to achieve, it is reasonable to assume

that alternative preventive measures such as the use of

fluoride would be unfortunate if public hopes were

raised to believe that dietary control alone would

solve the problem of dental caries.

See also: Carbohydrates: Metabolism of Sugars;

Digestion, Absorption, and Metabolism; Requirements

and Dietary Importance

Further Reading

Bibby BG (1981) Foods and dental caries. In: Hefferren JJ

(ed.) Foods, Nutrition and Dental Health, vol. 1,

pp. 257–278. Illinois: Pathotox.

Bowen WH, Amsbaugh SM, Monnel-Torrens S et al. (1980)

A method to assess cariogenic potential of foodstuffs. Jour-

nal of the American Dental Association 100: 677–681.

Duggal MS and Curzon MEJ (1989) An evaluation of the

cariogenic potential of baby and infant fruit drinks.

British Dental Journal 160: 327–330.

Edgar WM (1981) Plaque pH assessments related to food

cariogenicity. In: Hefferren JJ (ed.) Foods, Nutrition and

Dental Health, vol. 1, pp. 137–150. Illinois: Pathotox.

Edgar WM, Bibby BG, Mundorff S and Rowley J (1975)

Acid production in plaques after eating snacks: modify-

ing factors in foods. Journal of the American Dental

Association 90: 418–425.

Gustafsson BE, Quensel CE, Lanke LS et al. (1954) The

effect of different levels of carbohydrate intake on caries

activity in 436 individuals observed for five years. The

Vipeholm Dental Caries Study. Acta Odontologica

Scandinavica 11: 232–364.

King JD, Mellanby M, Stones HH and Green HN (1955)

The effect of sugar supplement on dental caries in chil-

dren. MRC Special Report Series, no. 288. London: Her

Majesty’s Stationery Office.

Navia JM et al. (1983) Nutrition in oral health and disease.

In: Stallard RE (ed.) A Textbook of Preventive Dentistry,

pp. 90–146. Philadelphia: WB Saunders.

Rugg-Gunn AJ, EdgarWM and Jenkins GN (1978) The effect

of eating some British snacks upon the pH of human

dental plaque. British Dental Journal 145: 95–100.

Stephan RM (1940) Changes in hydrogen ion concentration

on tooth surfaces and in carious lesions. Journal of the

American Dental Association 27: 718–723.

Fluoride in the Prevention of

Dental Decay

H Whelton, University College Cork, Cork, Ireland

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001Dental decay or caries is a ubiquitous disease in es-

tablished market economies and in many developing

countries. Dental caries poses a threat to the dentition

throughout life. The early caries lesion is known as a

‘white spot.’ This white spot can do one of three

things. It can stay the same, progress to a cavity, or

regress to sound enamel. The fate of the white spot is

influenced by its exposure to fluoride. Fluoride can

help to prevent progression of the lesion and can aid

remineralization, in which case the early white-spot

lesion can disappear clinically.

0002Fluoride is widely used in the prevention of dental

caries. It is estimated that over one billion people use

fluoridated toothpaste worldwide. The second most

common vehicle for fluoride is water. Water fluorid-

ation is the controlled addition of fluoride to a public

water supply for the purpose of preventing dental

caries. In many parts of the world, the level of fluoride

in water supplies is adjusted to 1 part per million

(ppm). It is estimated that about 317 million people

1754 DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay

in 39 countries benefit from artifically fluoridated

water. A further 40 million benefit from water supplies

which are naturally fluoridated. The fluoridation of

toothpastes and public water supplies has been ac-

knowledged as a major public health success in the

prevention of dental caries. The addition of fluoride to

water supplies and to oral health products has helped

to bring about a remarkable decline in dental caries

levels since the 1960s. In this paper the occurrence of

fluoride in nature, the history of the discovery of its

effects on the dentition, its use in the prevention of

dental caries, and the risks associated with ingestion of

excess fluoride will be considered.

Fluoride in Nature

0003 Fluorine is a naturally occurring element, apparently

ubiquitous in nature. Number nine on the periodic

table of the elements, it is a halogen gas. It ranks 13th

among the elements in order of abundance in the

earth’s crust. Fluorine is the most electronegative

and reactive of all elements. It is a pale yellow, corro-

sive gas, which reacts with practically all organic and

inorganic substances. The element was isolated in

1886 by Ferdinand Frederic Henri Moisson who

used an apparatus constructed from platinum. He

won the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 1906. Fluorine

occurs chiefly in fluorspar (or fluorite, calcium

difluoride, CaF

2

), cryolite (Na

2

AlF

6

), and in many

other minerals. Ionic fluoride, also referred to as in-

organic or free fluoride, is the biologically important

form of the mineral.

0004 Fluoride is found in fresh water, sea water, and earth

and in foods. Fluoride is present in both groundwater

and surface water. The level of fluoride in groundwater

varies from less than 0.1 mg l

1

to more than 25 mg l

1

according to the geological, chemical, and physical

characteristics of the water-supplying area. The fluor-

ide concentration in fresh surface water is generally

low, ranging from 0.01 to 0.03 mg l

1

. In sea water,

fluoride is found at approximately 1.5 ppm. Marine

plants and animals are therefore constantly exposed to

large amounts of fluoride. Fluoride in soils is derived

primarily from the geologic parent material. Samples of

nonindustrially contaminated soils from Germany,

Greece, Finland, Japan, Morocco, New Zealand,

Sweden, the USA and former USSR have been reported

as containing from 30 to 500 ppm fluoride. Soils near

fluorite and other types of mineralization may show

levels up to more than 5000 ppm.

0005 The normal accumulation of soil fluoride in plants

is small. However, a few species of plants are known

to accumulate high levels of fluoride, for example tea.

The concentration of fluoride in dried tea leaves

varies widely (approximately 4–400 ppm) while

those of brewed tea range from 1 to 6 ppm depending

on the amount of dry tea used, the fluoride concen-

tration of the water, and the brewing time. High levels

of fluoride are also found in fish: early reported con-

centrations range from 0.6 to 2.7 ppm. These samples

may have contained bones. With its high affinity for

calcium, most absorbed fluoride is deposited in bones

therefore fish bones are a source of concentrated

fluoride levels. More recent studies which excluded

bone fragments from fish reported a range of fluoride

values from 0.05 to 0.17 ppm. Other dietary constitu-

ents which contain fluoride are fluoridated water and

infant formulas and beverages reconstituted with

fluoridated water. Most other foods have fluoride

concentrations well below 0.05 ppm.

History of Water Fluoridation

0006In 1901 a letter in the US Public Health Report from

JM Eager of the US Public Health Service, stationed in

Naples, Italy, reported the occurrence of ‘a dental

pecularity’ known locally as denti di chiae. Denti di

chiae were called after Prof Stefano Chiae, a cele-

brated Neapolitan who first described the appearance

of a condition which was later to become known as

dental fluorosis.

0007A similar condition, known as Colarado brown stain,

was observed in Colorado Springs, USA, in 1901 by a

dentist, Fredrick McKay. The condition manifested itself

as a stain of varying intensity from fine white patches to

a disfiguring brown mottling. Some 87% of the popula-

tion in the area were affected. In 1916, McKay, with the

help of GV Black, a prominent figure in dentistry at the

time, published a thorough description of the condition,

describing its appearance as mottled enamel. By the

1920s McKay had suspected drinking water as the

source of the problem. In Oakley, Idaho, where mottling

was severe, McKay noticed that children living on the

outskirts of town who drank from a private spring had

no mottling. He advised the town to change to this

supply, which they did in 1925. Children born in the

town subsequently had no mottling.

0008In 1931 new methods of spectrographic analysis

led to the discovery of fluoride in the water supplies

of areas where mottled enamel was endemic. The

condition then became known as dental fluorosis.

0009In 1928 McKay published the observation that, in

areas where mottled enamel was found, the preva-

lence of dental caries appeared lower than would be

expected. In 1933 Ainsworth in England showed

that dental mottling in Maldon in Essex was associ-

ated with a high level of fluoride in its water (4.5–5.5

ppm). He also noted that the prevalence of caries in

permanent teeth amongst the children in the area was

lower than that for England and Wales as a whole.

DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay 1755