Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

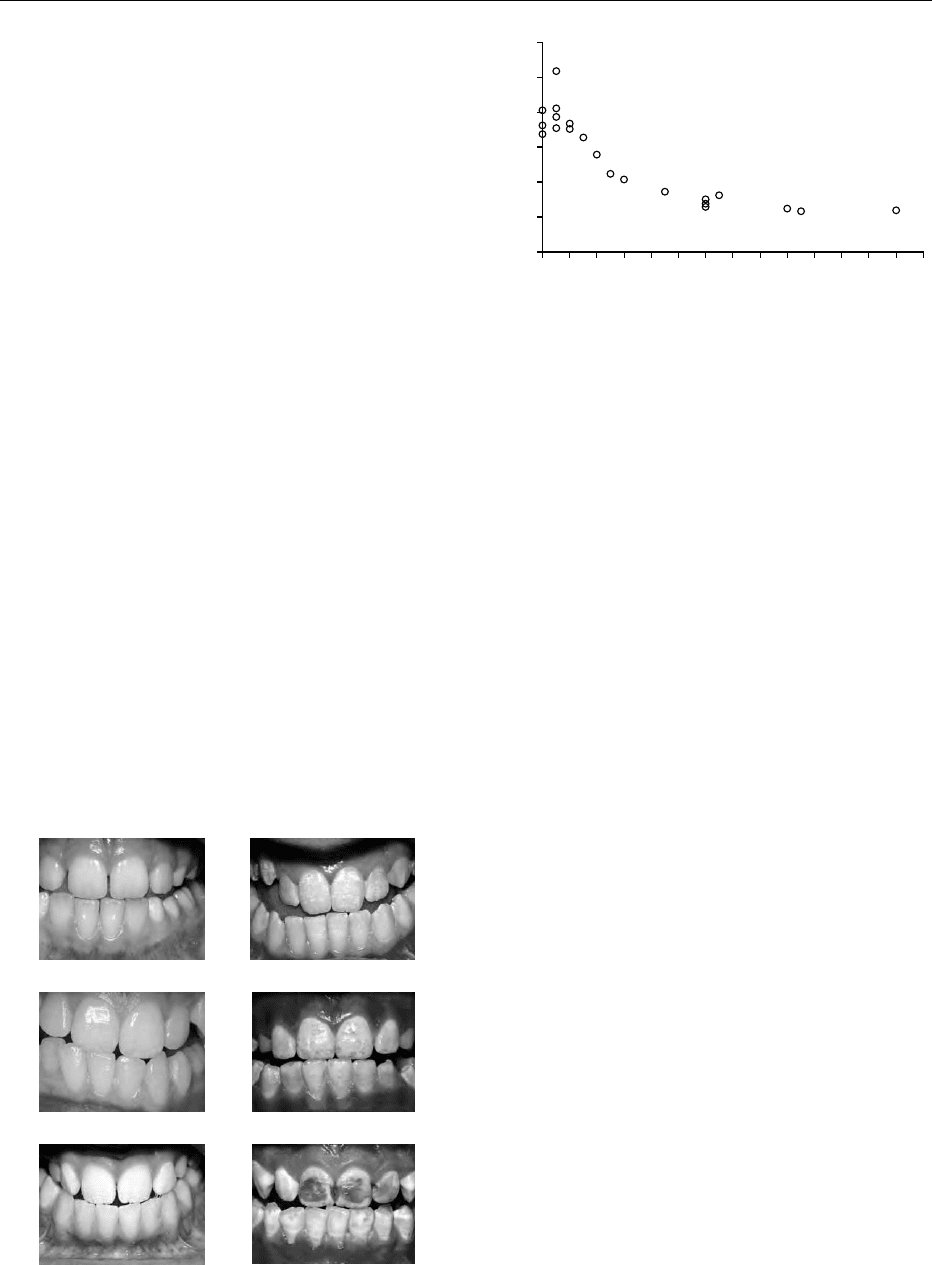

0010 The discovery of fluoride (known to act as a proto-

plasmic poison in some circumstances) as the causa-

tive agent in mottling of the teeth was a cause of

concern to the US Public Health Service. In response

they appointed a dentist, H Trendley Dean, to investi-

gate the condition. Dean devised a six-point scale of

severity of dental fluorosis which is still used today.

Dean’s index facilitates regional and international

comparisons of dental fluorosis as well as

temporal comparisons. However the index is rela-

tively subjective and the appearance of enamel varies

according to lighting conditions, drying of the

enamel, and angulation of viewing. Dean’s index cat-

egorizes the enamel into normal, questionable, very

mild, mild, moderate, and severe (Figure 1). Some of

the limitations of Dean’s index have since been over-

come by the development of a standardized photo-

graphic method for the recording of dental fluorosis.

0011 Dean combined measurement of the condition of

the enamel with analysis of the drinking water

throughout the USA. He then set out to identify the

water fluoride levels, which represented the best com-

promise between low caries experience and a level of

fluorosis, which could be deemed acceptable. The

resulting study became known as the ‘21 cities’

study. Dean recorded the level of dental caries and

dental fluorosis in 7257 12–14-year-old children who

had been lifetime residents of 21 cities with varying

levels of natural fluoride in their water supplies from

0.0 to 2.6 ppm.

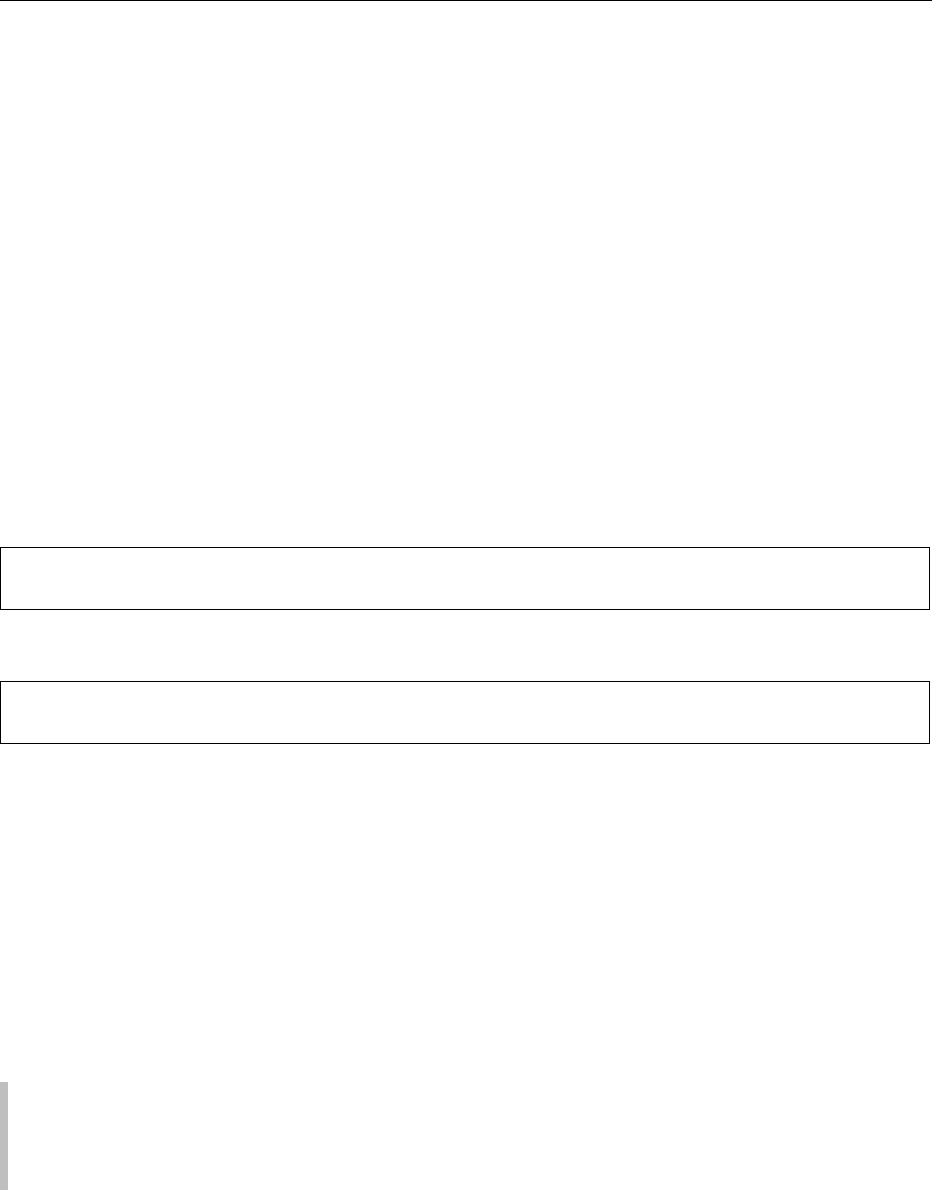

0012 The marked inverse association between the fluor-

ide content of the drinking water and the experience

of caries in the population is shown in Figure 2. This

study showed that, above a concentration of 1 ppm

fluoride in the water, very little further reduction in

caries was obtained. Dean also illustrated the dose–

response relationship between water fluoride levels

and dental fluorosis in the ‘21 cities study.’ He

found that, where the fluoride concentration exce-

eded 1.0 ppm, undesirable mottling would be seen

in about 10% of the population.

0013In 1945 and 1946 four cities in the USA and

Canada began to add fluoride to their water supplies

at a concentration of 1 ppm as part of the first con-

trolled field trials of water fluoridation. The fluorid-

ation of water to 1 ppm reduced the number of

carious teeth per child by on average 60% relative

to children in nonfluoridated cities.

Fluoridation Worldwide

0014Throughout the world it is estimated that about 317

million people drink artificially fluoridated water and

that a further 40 million drink water in which the

natural fluoride level is high enough to provide a

significant degree of protection against tooth decay.

Countries with fluoridation schemes include the

USA, Canada, Mexico, Argentina, Ireland, UK, Spain,

Australia, New Zealand, Hong Kong, and Singapore.

0015The USA is the most extensively fluoridated coun-

try in the world, with some 135 million people – over

half the population – currently receiving artificially

fluoridated water and another 10 million receiving

naturally fluoridated water. The national health pro-

motion and disease prevention objectives in Healthy

People 2010 call for increasing the percentage of

Normal

Questionable

Very mild

Mild

Moderate

Severe

fig0001 Figure 1 (see color plate 46) Categories of dental fluorosis

according to Dean’s index.

0

0

2

4

6

8

10

12

0.2 0.4 0.6 0.8 1 1.2

Fluoride content of the public water supply (ppm)

Mean number of teeth decayed,

missing and filled due to caries

1.4 1.6 1.8 2 2.2 2.4 2.6 2.8

fig0002Figure 2 The relation between caries levels observed in 7257

selected 12–14-year-old white school children of 21 cities of four

states and the fluoride content (ppm, horizontal scale) of

public water supply. Open circles, DMFT (mean number of

teeth decayed, missing, and filled due to caries). (Reproduced

from F.J. McClure (ed.) (1962) Fluoride Drinking Waters, by kind

permission of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial

Research).

1756 DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay

Americans on public water supplies drinking fluorid-

ated water from 62 to 75%.

0016 Within the European Community (EC), the UK,

Ireland, and Spain are currently operating fluorid-

ation schemes. In Ireland, fluoridation of public water

supplies is mandatory. An EC directive relating to the

quality of water intended for human consumption (98/

83/EC) sets a maximum admissible concentration

(MAC) for fluoride at 1.5 parts of fluoride per million

parts of water, irrespective of climate.

0017 Some countries, such as France, Switzerland, and

Germany, have implemented salt fluoridation.

Fluoride Ingestion and Absorption

0018 Approximate estimates for daily dietary fluoride

intake are shown in Table 1. It is estimated that 75–

90% of daily fluoride intake is absorbed. Of that

absorbed, the amount excreted varies; it is estimated

that on average approximately 50% of absorbed

fluoride is excreted, primarily by the kidneys in

urine. In the very young more fluoride is retained.

Most retained fluoride is deposited in bone because

of its strong affinity for calcium.

0019 Assessing fluoride levels in plasma, ductal saliva, or

in urine can help monitor recent total fluoride expos-

ure of individuals or populations. Research is ongoing

into the use of fingernail clippings as a biomarker for

fluoride intake some weeks prior to clipping. Dental

fluorosis is a convenient biomarker for fluoride

intake; however it is relevant only to the first 6 years

of life. Dental fluorosis is a convenient biomarker for

fluoride intake, however it is relevant only to the first

6 years of life. Dental hard tissues provide a marker

for fluoride exposure during defined developmental

periods. Bone provides information on the accumu-

lated body burden of fluoride over a lifetime.

Fluoride Toothpastes

0020 Studies of the effectiveness of fluoride toothpaste in

the 1940s and early 1950s failed to demonstrate a

caries-preventive effect. It is now believed that the

sodium fluoride was not bioavailable due to a reac-

tion with the calcium carbonate or calcium orthopho-

sphate abrasive in the formulation. Since the 1950s

studies of 2–3 years’ duration have reported that

fluoride toothpaste reduces caries experience among

children by a median of 15–30%. A dose–response

relationship has been demonstrated showing greater

caries-preventive effects for higher-dose fluoride

toothpaste. The two most commonly used forms of

fluoride added to toothpaste are sodium fluoride

(NaF) and sodium monofluorophosphate (MFP).

There are many different formulations of fluoride

toothpaste on the market. The concentration of fluor-

ide in toothpastes varies from 250 to 2800 ppm. The

most commonly sold toothpastes contain 1000–1500

ppm. In the European Union the maximum permis-

sible concentration in fluoride toothpaste to be sold

over the counter is 1500. Hence toothpaste formula-

tions with greater than 1500 ppm fluoride are avail-

able at pharmacies only.

0021Manufacturers commonly list fluoride levels in

toothpaste as a percentage. Table 2 shows the com-

mon percentages of NaF and NaMFP found in tooth-

pastes, expressed as ppm in toothpaste.

0022Fluoride toothpaste contributes to the risk of

enamel fluorosis because the swallowing reflex of

children aged under 6 years and especially in those

aged under 3 years is not well controlled. Early use of

fluoride toothpaste by children is associated with the

development of dental fluorosis. Ingestion of exces-

sive amounts of toothpaste during the period of

enamel formation can cause fluorosis. Enamel forma-

tion for all of the anterior teeth and most of the

posterior teeth is complete by age 7. The critical

window of vulnerability for anterior teeth to develop

fluorosis from ingested fluoride has been reported to

be 15–24 months for boys and 21–30 months for

girls. The amount of toothpaste used accounts

for an estimated 60% of the variation in the amount

of toothpaste swallowed by children under age 7. It

takes 0.75–1.0 g of toothpaste to cover a full head of a

child-sized toothbrush. For a 1000 ppm toothpaste,

this represents 0.75–1.0 mg fluoride. To minimize

toothpaste ingestion up to age 7, manufacturers

advise supervision and use of only a pea-sized amount

of toothpaste (0.25 g). Many experts also recommend

that toothpaste should not be used when brushing

children’s teeth up to the age of 2 years. The risk of

ingesting fluoride toothpaste has led to the develop-

ment of low-fluoride pediatric toothpastes with 250

or 550 ppm fluoride. These toothpastes have not been

shown to be as effective in preventing caries as the

tbl0001 Table 1 Estimated daily fluoride intake from dietary sources

Fluoridated area Nonfluoridatedarea

Adults 1.0–3.0 mg 1.0 mg

Children 0.5 mg 0.25 mg

tbl0002Table 2 NaF and NaMFP found in toothpastes, expressed as

percentages and as ppm in toothpaste

NaF (%) NaMFP(%) ppm

0.32 1.14 1500

0.22 0.76 1000

0.11 0.38 500

DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay 1757

1000 ppm formulation. Over the age of 7 years, when

there is little risk of swallowing toothpaste, children

who are able to expectorate the toothpaste properly

may be allowed to use a greater quantity of tooth-

paste with up to 1500 ppm fluoride.

Other Fluoridated Products

0023 Many other vehicles for the delivery of fluoride for

the prevention of dental caries have been shown to

be effective. Under the appropriate circumstances,

fluoridated salt (250 ppm) has been shown to be as

effective as water fluoridation. Fluoridated domestic

salt is available in Switzerland, France, and Germany.

Fluoridated milk and sugar have been tested on a pilot

basis. Among the other products available are fluoride

tablets for daily use, drops, mouth rinses for daily

(0.05% NaF, 230 ppm) or fortnightly (0.2% NaF,

910 ppm) use, and products for application by dental

professionals, including topically applied gels and var-

nishes. Applying fluoride gel (2.72% NaF, 12 300

ppm) or other products containing a high concentra-

tion of fluoride to the teeth leaves a temporary layer of

calcium fluoride-like material on the enamel surface.

The fluoride in this material is released when the pH

drops in the mouth in response to acid production and

is available to promote enamel remineralization.

Dental filling materials have also been developed

which release fluoride over time; however, fluoride

release is limited to a relatively short period after

placement. Other products have also been developed

for placement in the mouth which would slowly release

fluoride over months, if not years. Human clinical trial

data on the effectiveness of these products are not yet

available. Fortnightly school-based fluoride mouth

rinse programs for the prevention of dental caries

have been shown to be successful for the duration of

the program. However in programs that cease at age

12, the effects have been shown to fade after 4 years.

Mechanism of Action of Fluoride in the

Prevention of Dental Caries

0024 Dental enamel is a highly mineralized tissue made up

of 96% mineral and 4% organic material and water.

The inorganic content of enamel consists of a crystal-

line calcium phosphate known as hydroxyapatite.

The dissolution of these crystals by acid is the start

of the caries process. Fortunately, enamel can remi-

neralize as well as demineralize and the enamel sur-

face is in a constant seesaw between demineralization

and remineralization. Saliva provides a supersatur-

ated solution of ions and acts as an ion reservoir

during this process. When the equilibrium is dis-

turbed, caries can progress.

0025In the early days scientists thought that the anti-

caries activity of fluoride was a preeruptive systemic

effect as a result of its incorporation into the enamel

crystal to form fluorapatite during the time of enamel

formation. This crystal is more stable and resistant to

acid demineralization than hydroxyapatite. However,

investigators have failed to show a consistent correl-

ation between anticaries activity and the specific

amounts of fluoride incorporated into the enamel.

The theory of preeruptive fluoride incorporation as

the sole or principal mechanism of caries prevention

has been largely discounted. Another theory was that

fluoride inhibits bacterial metabolism; however, the

low levels of fluoride found in the mouth after tooth-

brushing with fluoride-containing dentifrices are in-

effective in interfering with processes of growth and

metabolism of bacteria. The current theory is that the

caries-preventive effect of fluoride is mainly attrib-

uted to the effects on demineralization/remineraliza-

tion at the tooth–oral fluids interface. Levels well

under 1 ppm of fluoride in saliva are effective in

shifting the balance from demineralization, leading

to caries, to remineralization. This is attributed to

the fluoride-enhanced precipitation of calcium phos-

phates, and the formation of hydroxyfluorapatite in

the dental tissues.

Benefits and Risks of Fluorides in

Contemporary Society

0026In the 1950s and 1960s dental caries was an over-

whelming problem in many countries. For example,

in Ireland prior to the introduction of water fluorid-

ation, in the early 1960s 12-year-old children had

on average five teeth with decay. In the 1990s 12-

year-old children whose domestic water supplies

were fluoridated had on average one decayed tooth,

and those without water fluoridation had on average

two decayed teeth. The dramatic decline in the level of

caries both in fluoridated and nonfluoridated areas

reflects changes seen in the other established market

economies.

0027Whilst early studies reported up to a 60% reduc-

tion in caries with water fluoridation, more recent

estimates of effectiveness are lower with an 18–40%

difference in caries levels. This apparent reduction in

effectiveness is probably due to the widespread use of

fluoridated toothpaste in both fluoridated and

nonfluoridated communities. In addition, the con-

sumption of foods and drinks manufactured using

fluoridated water and consumed in nonfluoridated

areas may confer some protection against dental

caries to populations in nonfluoridated areas. This is

known as the halo effect. Thus, where nonfluoridated

communities are exposed to fluoride from sources

1758 DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay

other than water, the observed effectiveness of water

fluoridation is reduced. In Ireland water fluoridation

was introduced in the 1960s and the use of fluorid-

ated toothpastes became widespread in the 1970s.

Whilst the level of caries has declined, the prevalence

of fluorosis amongst Irish children appears to have

increased since the 1980s when it was first measured.

The alteration in the pattern of caries, the changes in

the severity of the disease, and the use of multiple

sources of fluoride have prompted a number of

reviews of the risks and benefits of fluoridation. In

2000 the University of York presented a systematic

review of the evidence on the positive and negative

effects of population-wide drinking-water fluoridat-

ion strategies to prevent caries. The review summ-

arized the best available and most reliable evidence

on the safety and efficacy of water fluoridation. Of all

the studies found in the literature search, 214 satisfied

the inclusion criteria for consideration in the ap-

praisal of the evidence. Outcomes for the five object-

ives of the review are shown in Table 3.

0028 The reviewers were critical of the lack of high-

quality research on water fluoridation. They recom-

mended: ‘the evidence of a benefit of a reduction in

caries should be considered together with the

increased prevalence of dental fluorosis.’

0029 Those who oppose water fluoridation do so on

three main grounds:

1.

0030 the effectiveness of water fluoridation in prevent-

ing caries in contemporary society

2.

0031 the safety of water fluoridation. Concerns around

the general health effects of fluoride have been

raised. For example, fluoride has a high affinity for

calcium and most fluoride, which is absorbed and

not excreted, is deposited in bones, hence, the effect

of fluoride on bone health has been questioned

3.

0032the ethics of administering fluoride through the public

water supply and removal of the right to choose

whether one’s water supply is fluoridated or not

With regard to effectiveness, the current evidence con-

tinues to demonstrate a positive protective effect of water

fluoridation against dental caries. Concerning safety,

studies have failed to find harmful effects of water fluorid-

ation at 1 ppm. Finally, the ethical debate is a philosoph-

ical one and is outside the scope of this paper.

Conclusion

0033Fluoride has been shown to be effective in the control

of dental caries. Its effect is mainly topical at the

plaque–enamel interface. The aim of fluoride therapy

is to maintain the ambient level of the fluoride ion in

the saliva at a constant optimum level. The evidence

suggests that the effects of fluoridated water and

fluoride toothpaste are additive. However, the risk

associated with excessive ingestion and absorption

of fluoride is the development of dental fluorosis.

See also: Fluoride; Water Supplies: Chemical Analysis

Further Reading

Evans RW and Darvell BW (1995) Refining the estimate of

the critical period for susceptibility to enamel fluorosis

in human maxillary central incisors. Journal of Public

Health Dentistry 55(4): 238–249.

tbl0003 Table 3 Objectives and conclusions of the systematic review of public water fluoridation conducted by the NHS Centre for Reviews

and Dissemination, University of York, 2000

Objective Number of studies

includedinreview

Conclusion

The effects of

fluoridation of drinking water supplies

on the incidence of caries

26 The best available evidence

suggests that fluoridation of

drinking water supplies

does reduce caries prevalence

The effect over and above that offered by

the use of alternative interventions

and strategies

9 Water fluoridation has an

additional beneficial effect

The effect of water fluoridation on

levels of caries across social groups and

between geographical locations

15 Inconclusive evidence

Negative effects

Fluorosis 88 Yes, dose–response relationship with

water fluoridation

Bone fracture and bone

development problems

29 No association found

Cancer 26 No association found

Other negative effects 33 No clear association found

Differences in the effects of

natural and artificial water fluoridation

Not enough evidence to draw conclusions

DENTAL DISEASE/Fluoride in the Prevention of Dental Decay 1759

Fejerskov O, Ekstrand J and Burt BA (1996) Fluoride in

Dentistry, 2nd edn. Copenhagen: Munksgaard.

Fluorine in web elements. http://www.webelements.com.

Holland TJ, Whelton H, O’Mullane DM and Creedon P

(1995) Evaluation of a fortnightly school-based sodium

fluoride mouthrinse 4 years following its cessation.

Caries Research 29(6): 431–434.

Mascarenthas AK and Burt BA (1998) Fluorosis risk from

early exposure to fluoride toothpaste. Community

Dental and Oral Epidemiology 26(4): 241–248.

Murray JJ, Rugg-Gunn AJ and Jenkins AN (1991) Fluorides

in Caries Prevention, 3rd edn. Oxford: Wright.

NHS CRD (2000) A systematic review of public water

fluoridation. Report 18. York: NHS Centre for Reviews

and Dissemination, University of York.

Taves DR (1983) Dietary intake of fluoride ashed (total

fluoride) v. unashed (inorganic fluoride) analysis of indi-

vidual foods. British Journal of Nutrition 49: 295–301.

ten Cate JM (1999) Current concepts on the theories of the

mechanism of action of fluoride. Acta Odontologica

Scandinavica 57: 325–329.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2000)

Healthy People 2010. Washington: US Department of

Health and Human Services.

US Department of Health and Human Services (2000) Oral

Health in America: A Report of the Surgeon General.

Rockville, MD: US Department of Health and Human

Services, National Institute for Dental and Craniofacial

Research, National Institute of Health.

US Department of Health and Human Services Center for

Disease Control and Prevention (2001) Morbidity and

Mortality Weekly Report 50: no. RR-14.

Wang NJ, Gropen AM and Ogaard B (1997) Risk factors

associated with fluorosis in a non-fluoridated popula-

tion in Norway. Community Dental and Oral Epidemi-

ology 25(6): 396–401.

Whitford GM (1996) The Metabolism and Toxicity of

Fluoride, 2nd edn. Basel: Karger.

World Health Organization (1994) Report of a WHO

Expert Committee on Oral Health Status and Fluoride

Use. Fluorides and Oral Health. Geneva: WHO.

Detergents See Cleaning Procedures in the Factory: Types of Detergent; Types of Disinfectant; Overall

Approach; Modern Systems

Detoxification See Toxins in Food – Naturally Occurring; Alkaloids: Properties and Determination;

Toxicology

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND

NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS

Contents

Down Syndrome

Prader–Willi Syndrome

Down Syndrome

B Lucas and S Feucht, University of Washington,

Seattle, WA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Etiology

0001 Down syndrome (DS) (Trisomy 21) is one of the most

common chromosomal abnormalities, affecting one

in 600 live births. DS results from the presence of

extra genetic material (a third copy) on chromosome

21. It occurs during the prenatal period and affects all

races. The incidence of DS increases with maternal

age, although 80% of children with DS are born to

mothers less than 35 years of age due to increased

fertility of younger women. Current knowledge de-

scribes three types of genetic changes in chromosome

21 that cause DS:

.

0002nonfamilial trisomy 21, occurring in 95% of

individuals;

1760 DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Down Syndrome

.0003 unbalanced translocation between chromosome

21 and another chromosome, in 3–4%; of these,

approximately 25% result from a familial balanced

translocation, and parents may be at increased risk

of having another child with DS;

.

0004 mosaicism, in 1–2% of individuals with DS,

resulting from two present cell lines – one normal

and one trisomy 21; these individuals are usually

affected less severely than the other types.

Recent research has studied the role of folate and

homosysteine metabolism in women who had

children with DS. Although no conclusions could be

drawn from the small numbers, more work is needed.

It is possible that both genotype and nutrition may

play a role in the etiology of DS, as it does with neural

tube defects.

Features and Characteristics

0005 Individuals with DS demonstrate physical features

and other characteristics that define the syndrome

and determine the extent of health care, special edu-

cation, therapies, and vocational planning needed.

Developmental delay, hypotonia (reduced muscle

tone), and short stature are seen in all individuals

with DS. Cognitive levels usually range from mild

to moderate mental retardation. See Table 1 for

common characteristics.

0006 Overweight and obesity are frequently seen in indi-

viduals with DS, resulting from a variety of factors.

Other health concerns occurring less frequently, but

impacting nutrition, feeding, or physical activity,

include congenital heart disease, hearing problems,

vision problems, cervical spine abnormalities, seizure

disorders, and thyroid disease.

0007 Down syndrome is associated with premature

aging, often beginning in the fourth and fifth decades

of life. Along with this aging, there is reported to be

an increased incidence of Alzheimer’s disease, senility,

autoimmune diseases, and cataracts. Preliminary

studies had documented in vitro chronic oxidative

stress in persons with DS compared with their control

siblings, but the role of this or other biomarkers in

accelerated aging is controversial.

0008Services for individuals with DS are primarily com-

munity-based, compared with the past when most of

this population would be found in residential insti-

tutions. Currently, the diagnosis is made at, or shortly

after, birth, and early intervention services and

therapies are begun in early infancy. Full inclusion

in social, educational, and work environments is

supported in most all communities and countries. As

adults, many people with DS live in the community

(with family, in group or individual homes) and are in

vocational programs or gainfully employed.

Growth

0009Individuals with DS grow more slowly and are

shorter in final stature than those without the syn-

drome of the same age and sex. The growth differ-

ences begin in the prenatal period. By puberty,

children with DS are typically 1–2 inches (2.5–5 cm)

shorter than their peers. The onset of the growth spurt

may be delayed 6–12 months in adolescents with DS,

and some may never have a growth spurt. Specific

medical conditions such as congenital heart disease

may also impact growth and weight gain for a child

with DS. Since the onset of overweight can begin in

late infancy or the preschool period, appropriate

prevention strategies by the health care team should

begin early.

Specialized Growth Charts

0010Specialized growth charts have been published for

children with DS from birth to 36 months of age

and from 2 to 18 years of age. They provide a better

picture of length or stature in relation to other chil-

dren with DS. These DS charts reflect small sample

numbers (longitudinal data for weight and length/

height for 400 males and 300 females), and include

some children with congenital heart disease. The data

were collected from 1960 to 1986 on children living

at home, and they reflect a tendency to overweight. It

is essential to use these specialized charts in combin-

ation with standard growth charts, such as the Center

for Disease Control Growth Charts: United States

2000. The DS charts do not include head circumfer-

ence data for younger children, nor do they compare

weight/length or height in younger children or body

mass index for children over the age of two.

Overweight and Obesity

0011Increasing rate of weight gain is a risk in persons with

DS due to physical characteristics, medical condi-

tions, and environment (see Table 2). With wellness

tbl0001 Table 1 Characteristics of persons with Down syndrome

Hypotonia

Mental retardation

Short stature

Flat facial profile

Eye features (upward slanting eyelids; skinfolds in corners of

eyes)

Dental hypoplasia and irregular tooth placement

Increased risk of overweight and obesity

Accelerated aging process, i.e., Alzheimer-like brain changes,

cataracts

Increased incidence of congenital heart disease, thyroid disease,

leukemia

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Down Syndrome 1761

programs for this population and their families/care-

givers, however, obesity can be prevented. A 1992

study of 30 sibling pairs, aged 2–14, found no signifi-

cant differences between the DS children and their

siblings in terms of BMI. The children with DS were

less active than their siblings. Although children with

DS who grow up with their own families have less

overweight and obesity than their institutionalized

peers, adults with DS living in the community are

more likely to be overweight or obese than those in

institutional settings. In 1995, Prasher reported on an

assessment of overweight and obesity in 201 adults

with DS living in the UK. Using BMI values, 31%

of males were overweight, and 48% were obese

(BMI > 30). For females, 22% were overweight, and

47% were obese; they also had the more severe

forms of obesity. This study found no association

between overweight/obesity and the severity of learn-

ing disability. Of note was the decreasing fall in BMI

with increasing age, but it is unclear if this is an

effect of the precocious aging or other related medical

conditions.

0012 For children, weight should be closely monitored

on standard growth charts to prevent rapid or exces-

sive gain that may not be as clearly seen on the DS

charts. Overall, the velocity of growth and weight

gain is more important than the actual percentile on

either growth chart (see Table 3). For adults, regular

health assessment should include weight and BMI

monitoring. Adults with DS and their older parents

may not have had the benefit of early intervention

programs and may not be as enthusiastic about phys-

ical fitness and healthy diet plans as younger persons.

Regardless of the etiology, the hazards of obesity

make prevention and intervention important.

0013Inclusion in social, educational, and vocational

environments brings new dietary challenges. Food

choices, from vending machines and fast food outlets,

typically favor high-fat, high-energy, nutrient-poor

foods and beverages. Nutrition education is required

to assist individuals with DS to make healthy food

choices for themselves in their communities.

Nutrition and Feeding Issues

0014Individuals with DS require the same nutrients and a

varied healthy diet as anyone else. However, the syn-

drome characteristics may make them more at risk for

nutrition and feeding problems. Owing to early de-

velopment delays, some feeding issues can arise that

affect the overall nutrient intake. Some infants may

be poor feeders due to hypotonia. As the child grows,

delays may be seen in the introduction of textured

foods and the transition to feeding themselves table

foods. Concerns have also been raised about low

energy intake, which may result from efforts to pre-

vent excessive weight gain. This low energy intake

may lead subsequently to a low nutrient intake.

With adequate monitoring and teamwork with the

family, issues around feeding and nutrition can be

identified early and appropriate interventions con-

sidered. Table 4 provides some general guidance to

support positive development of food habits and

prevention of excessive weight gain.

tbl0002 Table 2 Risk factors for overweight and obesity in individuals

with Down syndrome

Risk factors Effect

Hypotonia

Short stature

Low resting metabolic rate Easily tired

Hypothroidism Excess energy intake

Decreased pulmonary function Poor food choices

Cardiac malformations

Premature aging

Limited instruction in wellness

Food used as a reward

Limited physical activity

Preference for indoor

activities

Disinterest in physical

exercise

Adapted from Pipes P and Powell J (1996) Preventing obesity in children

with special health care needs. Nutrition Focus Newsletter 11(6): 1–8.

tbl0003 Table 3 Guidelines for growth monitoring and obesity

prevention in children with Down syndrome

Use standard growth charts for assessing weight for length,

weight for height, and/or body mass index (BMI)

Down syndrome-specific growth charts may be used with parents

to compare their children with their peers for length/height

Height and activity level should be used to determine individual

energy requirements (a baseline for children 5–11 years of age

is 16.1 kcal (67 kJ) per centimeter of height for males and

14.3 kcal (60 kJ) per centimeter of height for females)

Physical exercise is an important adjunct to an appropriate diet to

increase lean body mass and, if needed, decrease fat tissue

tbl0004Table 4 Nutrition recommendations for children with Down

syndrome

Establish early acceptance of a variety of foods

Develop a predictable eating pattern, i.e., three meals a day and

snacks, if needed

Eat together as a family as often as possible; do not expect the

child to eat alone

To establish good food habits early, limit access to non-nutritious

foods

Carry low-energy foods, e.g., vegetable juice, fruit, when away

from home

Have water readily available to drink

Avoid the use of food reinforcers in educational settings or for

behavior management

Physical activity limits excessive snacking while increasing

energy expenditure. (Note: To prevent aspiration, children

should not be engaged in physical activity while eating.)

Adapted from Pipes P and Powell J (1996) Preventing obesity in children

with special health care needs. Nutrition Focus Newsletter 11(6): 1–8.

1762 DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Down Syndrome

Energy and Nutrient Intake

0015 Since body mass and rate of growth determine basal

energy expenditure, individuals with DS require less

energy than their peers. Several studies of 5–11-year-

old children, living either in an institution or at home,

reported less energy intake than what is recom-

mended for their age groups, or compared with the

intake of their typically developing siblings. Obese

teenagers with DS consumed 12–13 kcal (50–54 kJ)

per cm (between the 10th and 50th percentile of

energy intake for typically developing teens).

0016 Over the years, nutrients of concern in children

with DS have included calcium, iron, copper, zinc,

and vitamins A, C, and E. Some reports have shown

the overall intake of vitamins and minerals to be

lower in children with DS compared with their con-

trols. This is a concern for those children with a lower

weight/height ratio and may be related to food/energy

restriction. Earlier vitamin A studies demonstrated a

lower intake, decreased absorption, and decreased

plasma levels of retinol. How this might relate to

abnormal immune response remains speculative.

0017 A recent study by Hopman of 44 children (birth to

4 years) with DS indicated that, while there was

delayed introduction of solid foods, the overall nutri-

ent intake was adequate. Iron was the exception, and

was low for both the subjects and controls. Energy

intake was 27% below the RDA, but when assessed

using energy per kilogram of body weight, this group

reached the recommended level (102 kcal (427 kJ)

per kg). These young children with DS as a group

weighed less than their controls and were younger

than those previously studied. With concerns about

low energy intake and the risk of inadequate nutrient

intake, a nutrition referral is appropriate for children

with Down syndrome, especially in the early months

and years of life.

Feeding Problems

0018 Feeding difficulties and concern about related nutri-

ent intake occur most often during the infant, toddler,

and preschool years. If feeding issues continue into

older childhood, they may have multiple causes and

be more severe. Early feeding problems may include

difficulties with coordination of suck and swallow.

Most infants with DS are not ready for semisolids by

the usual 4–6 months of age. They are usually not

able to sit without support due to the hypotonia, and

immature oral motor abilities make eating from a

spoon difficult, if not unpleasant. If solids are not

offered when the child is developmentally ready,

however, subsequent feeding problems can occur.

Delays in introducing solid foods due to oral motor

issues sometimes can lead to a refusal to progress and/

or chew more textured foods when the child is

developmentally able to do so.

0019Because of the delayed development, parents often

do not have adequate guidance or cues regarding

when and how to progress in food textures and self-

feeding skills. Feeding problems can also develop from

negative experiences and interactions around feeding,

i.e., choking or gagging, force-feeding. Infants and

children with DS benefit from periodic screening to

assess feeding development with subsequent referral

to therapists or a feeding team if concerns are present.

This screening should begin in infancy.

Supplement Use in Down Syndrome

0020The use of alternative treatments, such as supplemen-

tal vitamins and minerals, is relatively common in

individuals with developmental disabilities. Vitamin

supplements, with varying formulations and some-

times at high levels, have been promoted for persons

with Down syndrome for at least 60 years. Related to

the theory of increased oxidative stress, there have

been various studies using individual nutrient supple-

ments, i.e., zinc, vitamin A, selenium, and vitamin B

6

.

The results of these studies were inconsistent, and

most had major methodological limitations.

0021The current popular approach is ‘targeted nutrition

intervention.’ The supplement promoted promises to

‘alleviate certain harmful symptoms of Down syn-

drome (e.g., the susceptibility to infections), and at-

tempt to keep other harmful effects of the syndrome

(e.g., mental retardation) from getting worse.’ It

contains vitamins and minerals for which there is a

dietary reference intake (DRI) or a recommended

dietary allowance (RDA), amino acids, and other

compounds such as coenzyme Q10 and papain,

which have no established dietary requirement.

When provided as recommended for a child’s weight,

the supplement does not provide excessive doses of

fat-soluble vitamins, which could lead to toxicity.

However, some of the water-soluble vitamins are ex-

cessively high for infants, i.e. 60 times the dietary

reference intake for vitamin B

12

. Although such high

levels are not reported to be deleterious in adults,

studies in infants and young children are virtually

nonexistent. Therefore, monitoring of these supple-

ments is indicated, as well as education and counsel-

ing for families regarding recommended nutrient

intakes for infants and children.

0022Anecdotal reports and testimonials of the benefits

of these and similar supplements are widely distrib-

uted in lay publications and on the Internet, but no

controlled studies have been conducted on these

supplements.

0023When a similar supplement was popular in the

1980s, several double-blind, controlled studies using

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Down Syndrome 1763

the same protocol were conducted with children with

DS. There was no difference in the health, develop-

ment, and cognition between the children receiving

the supplements and those who received the placebo.

All groups showed improvements in all areas, as

would be expected over time.

0024 Health and education professionals working with

families who are using such supplements need to be

supportive and open, yet make sure that the practice

does no harm. They should ask: Is the product safe?

Does it work? What is the cost to the family? Are diet,

feeding, and growth concerns being addressed at the

same time? Is the child still obtaining education and

needed therapies?

Other Nutrition-related Issues

Constipation

0025 Constipation is a frequent problem due to hypotonia

and decreased motor activity. The colon may retain

stool longer leading to loss of water and result in

hard, dry stools and long periods between stooling.

Typical interventions include increasing the amount

of fiber-containing foods and fluids in the diet and

participating in appropriate exercise. If feeding prob-

lems are present, dietary treatment may be a challenge.

Behavior-management techniques are sometimes help-

ful. Additional medical management may be needed

with the use of stool softeners or addition of medical

fiber products. Generally, the use of laxatives, supposi-

tories, etc. is not appropriate for children, unless the

child’s primary care provider is consulted.

0026 Children with DS have an increased incidence of

Hirschsprung disease. In this condition, nerve endings

are missing in the colon, so stools are not pushed

along in the large intestine. This condition is usually

identified early in life with subsequent surgical inter-

vention.

Celiac Disease

0027 Celiac disease may occur in 7–16% of children with

DS, mostly documented from European sources.

Individuals with DS may be predisposed to this

condition because of the known increased incidence

of autoimmune disorders. Symptoms usually resolve

following institution of a gluten-free diet.

Dental Issues

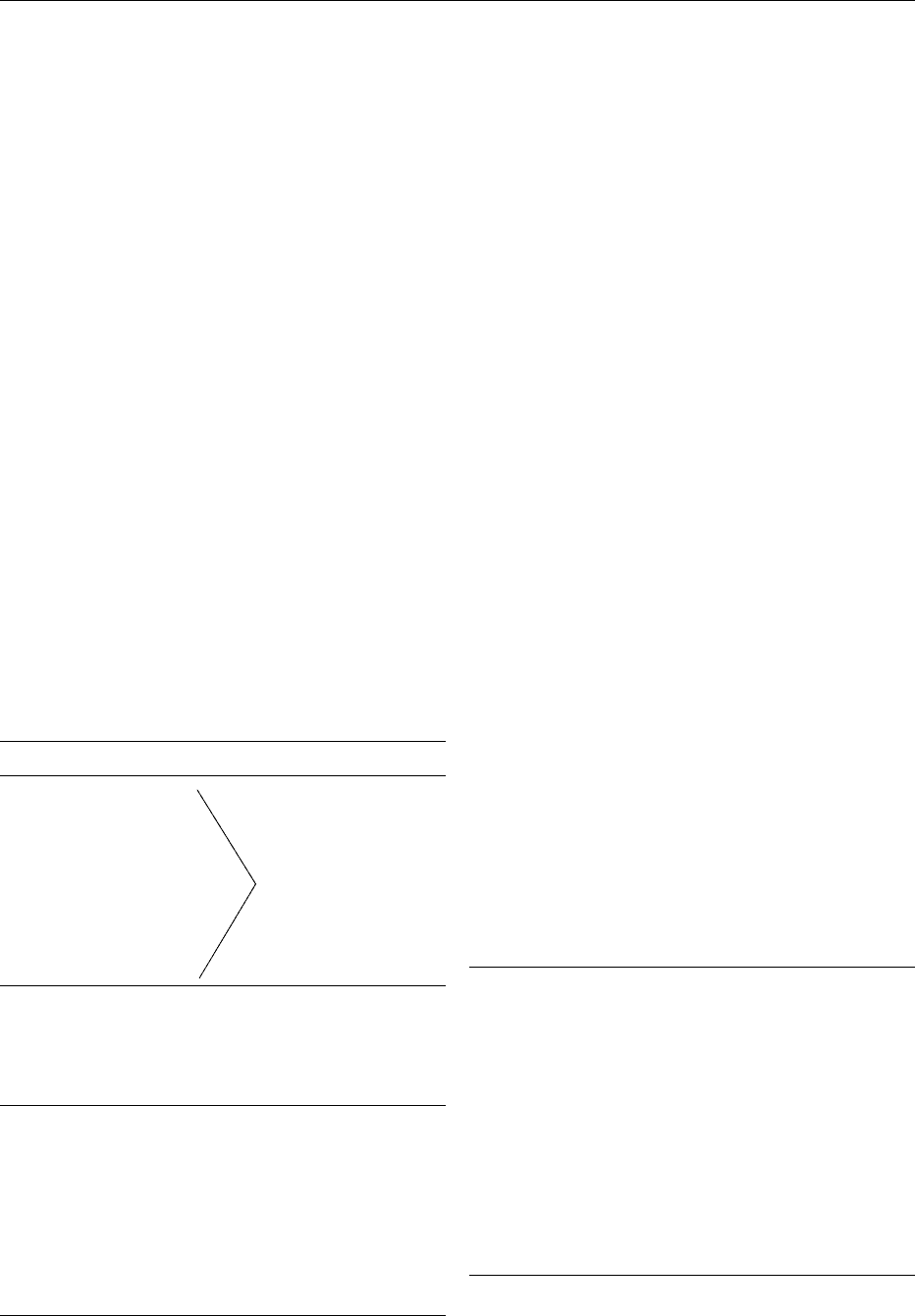

0028 Persons with DS often have smaller jaws and palates.

Protruding of the lower jar can lead to poor align-

ment, which can affect chewing. The tongue also may

be increased in size (or the jaw may be too small to

support the tongue) and be more furrowed, leading to

crevices that retain food and plaque. This can foster

bacteria growth and/or bad breath. Dry mouth

(xerostomia) is common and is believed to be due to

reduced saliva as well as an open mouth and mouth

breathing due to the tongue and jaw size.

0029Tooth eruption is delayed in children with DS until

12 and 18 months of age. There is also a risk for

enamel abnormalities that can cause pitting and re-

tention of food and plaque. Gum disease also occurs

with greater frequency.

0030These problems can impact the individual’s ability to

eat and chew. With the increased risks of dental prob-

lems that can impact food intake, early and regular

tooth and gum care is essential. For children with DS,

the first visit to the dentist is recommended immedi-

ately after the first teeth erupt or by the first birthday.

Physical Activity

0031Individuals with DS are known to be less active than

peers and to spend significantly more time indoors.

Hypotonic children tire easily and use movement

patterns requiring the least expenditure of energy.

However, hypotonia tends to improve with age and

therapy. The low level of physical fitness is partially

explained by findings such as blood pressure, which

does not rise regularly with the workload increment.

The Health Care Guidelines for Individuals with

Down Syndrome recommend establishing regular

exercise and recreational programs early in the child’s

life. Enrollment in an early intervention program,

which includes a focus on gross motor activities, is

usually recommended within the first months of life.

0032Many children with DS have few restrictions in

physical activity and should be encouraged to be active

to increase their function, improve fitness, expend

energy for weight management, and have fun. Sports

should be limited to noncontact sports that challenge

development, coordination, balance, and agility, and

are fun to encourage life-long participation. The

Special Olympic programs fosters life-long participa-

tion in physical activity and has many social rewards.

0033Approximately 10–40% of individuals with DS

have atlantoaxial dislocation (ligaments in the cer-

vical vertebra are more relaxed) resulting from hypo-

tonia. This instability may increase the risk for spinal

cord compression and injury. Activities that cause or

require significant flexion of the neck, such as high

jumping, gymnastics, diving and the butterfly stroke,

should be avoided or done under medical supervision.

Promotion of Health and Nutrition

0034Optimal nutrition and growth, a healthy weight, and

overall wellness are positive goals for persons with DS

1764 DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Down Syndrome

and their families/caregivers. These are achieved not

only by appropriate health care, but also by health

and nutrition curricula in educational settings, and

wellness programs in vocational and work sites. Key

elements in a comprehensive wellness program for

individuals with DS throughout the life span include:

.

003 5 access to accurate and consistent nutrition, well-

ness, and fitness information and anticipatory

guidance;

.

003 6 interdisciplinary health care teams who develop

trusting relationships with families and support

access to scientific information and interpretation

of that information;

.

003 7 focus on good food choices and appropriate

physical activity (beginning in infancy) to prevent

overweight and obesity;

.

003 8 practical nutrition education (appropriate to cog-

nitive level) related to good food choices, basic

food preparation, and physical activity for older

children and adults with DS in the community.

Seealso: Developmental Disabilities and Nutritional

Aspects:Prader–WilliSyndrome; Gene Expression and

Nutrition; Pregnancy:MaternalDiet,Vitamins,and

NeuralTubeDefects; Slimming:MetabolicConseqences

ofSlimmingDietsandWeightMaintenance

Further Reading

American Academy of Pediatrics (1994) Health supervision

for children with Down syndrome. Pediatrics 93:

855–859.

Ani C, Grantham-McGregor S and Muller D (2000) Nutri-

tional supplementation in Down syndrome: theoretical

considerations and current status. Developmental

Medicine and Child Neurology 42: 207–213.

Cohen WI (ed.) (1996) Health Care Guidelines for Individ-

uals with Down Syndrome (Down Syndrome Preventive

Medical Check List). Down Syndrome Quarterly 1: 2

(available at http://denison.edu/dsq).

Cronk CE, Crocker AC, Pueschel SM et al. (1988) Growth

charts for children with Down syndrome 1 month to 18

years of age. Pediatrics 81: 102. (Note: the birth to 36

month chart for males and females has errors in the

weight increments).

Hobbs CA, Sherman SL, Yi P et al. (2000) Polymorphisms

in genes involved in folate metabolism as maternal risk

factors for Down’s syndrome. American Journal of

Human Genetics 67: 623–630.

Hopman E, Cszimadia CG, Bastiani WF et al. (1998) Eating

habits of young children with Down syndrome in The

Netherlands: Adequate nutrient intakes but delayed

introduction of solid food. Journal of the American

Dietetic Association 98: 790–794.

James SJ, Pogribna M, Pogribny IP et al. (1999) Abnormal

folate metabolism and mutation in the methylenetetra-

hydrofolate reductase gene may be maternal risk factors

for Down syndrome. American Journal of Clinical

Nutrition 70: 495–501.

Luke A, Sutton M, Schoeller DA and Roizen NJ (1996)

Nutrient intake and obesity in prepubescent children

with Down syndrome. Journal of the American Dietetic

Association 96: 1262–1267.

National Down Syndrome Congress. Atlanta, GA

(www.ndscenter.org).

Prasher VP (1995) Overweight and obesity amongst

Down’s syndrome adults. Journal of Intellectual Disabil-

ity Research 39: 437–441.

Sharar T and Bowman ST (1992) Dietary practices, physical

activity, and body-mass index in selected population of

Down syndrome children and their siblings. Clinical

Pediatrics 31: 341–344.

Prader–Willi Syndrome

M S N Gellatly, Chelmsford, Essex, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Prevalence and Incidence

0001Prader-Willi Syndrome (PWS) is a complex genetic

disorder.

0002In early 2002, the best estimate of incidence is 1 in

38 000–40 000. Increased awareness of the syndrome

and improved diagnostic procedures should not be

confused with an increase in prevalence.

0003PWS occurs in all races and across all ethnic

groups.

Characteristics

0004The documented characteristics of PWS are summar-

ized in Table 1. The range and severity of these vary

considerably.

Body Composition

0005People with PWS have an abnormal body compos-

ition. Part of the explanation can be attributed to

lowered gonadal hormones and their contribution to

normal development. The most significant abnormal-

ity is a peculiarly high fat to fat-free mass ratio. Bone

composition irregularities include lower mineral

density, which contributes to the increased risk of

osteoporosis, while bone age may be advanced if the

child is significantly obese. Hypotonia (poor muscle

tone) is primarily caused through central nervous

system abnormalities; muscle abnormalities may be

observed, such as size variations in type 1 and defi-

ciencies in type 2B fibers.

DEVELOPMENTAL DISABILITIES AND NUTRITIONAL ASPECTS/Prader–Willi Syndrome 1765