Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

mostly on strong anion exchange (SAX) columns

using buffered mobile phases such as borate and

perchlorate mixtures and gradient elution. Azo dyes

and sulfonated intermediates can be separated using

weak anion exchange (WAX) columns with citric

acid mobile phase at pH 2.8. Because of poor repro-

ducibility (notably with the use of gradient elution),

the requirement for aggressive buffer systems and its

consequently relatively short column life, ion ex-

change has been largely superseded by reverse-phase

HPLC for the analysis of synthetic water-soluble

dyestuffs.

Reverse-Phase HPLC

0064 Synthetic dyes require buffered eluants to achieve

optimum pH conditions for desired separations on

reverse-phase HPLC, usually with organic mobile

phase modifiers methanol or acetonitrile. The column

materials used are short-chain (C

2

), octyl (C

8

), and

octadecyl (C

18

) alkyl-bonded silicas, though other

bonded phases such as amino (NH

2

) and cyano

(CN) have also been employed. Considerable inter-

est has been shown in the use of macroporous and

highly cross-linked polystyrene-divinylbenzene co-

polymer column packing materials. The mobile

phase may alter the affinity of ionic species for the

stationary phase by both ion suppression and ion-

pairing mechanisms.

0065Reverse-phase-HPLC with ion suppression has

been used to separate and identify various dyes,

eluting with phosphate buffers at various pH values

and methanol. Ammonium acetate has recently been

successfully used in this mode of reverse-phase

HPLC.

0066Ion-pair HPLC is perhaps the most widely used

chromatographic technique for the analysis of dyes,

subsidiary colors, and uncombined intermediates in

foodstuffs. Many published methods are available.

Most favored are ion-pair reagents derived from

quaternary ammonium compounds such as cetyltri-

methylammonium bromide (cetrimide) and tetra-

butylammonium phosphate. Again, buffered mobile

phases modified with organic solvents are generally

used.

0067Both isocratic and gradient systems can be

employed to separate dye mixtures; the latter is

often preferred for the separation of complex mix-

tures. Modern high-performance and computer-aided

instrumentation permits the use of many powerful

techniques which may be readily applied to aid in

the analysis of dyestuffs. These include:

.

0068automated sample handling and processing

.

0069automated chromatographic methods develop-

ment

.

0070high-sensitivity multiple-wavelength and diode-

array detectors

5

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

1

2

5

6

7

3

4

10

Time (min)

mAU

15 20 25

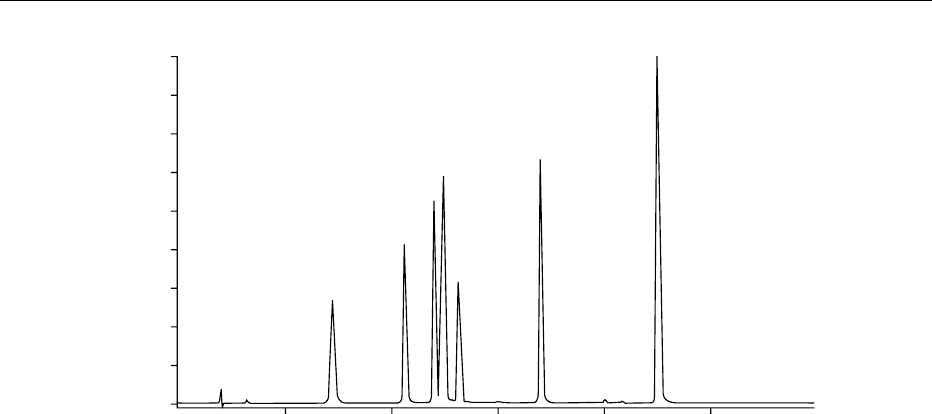

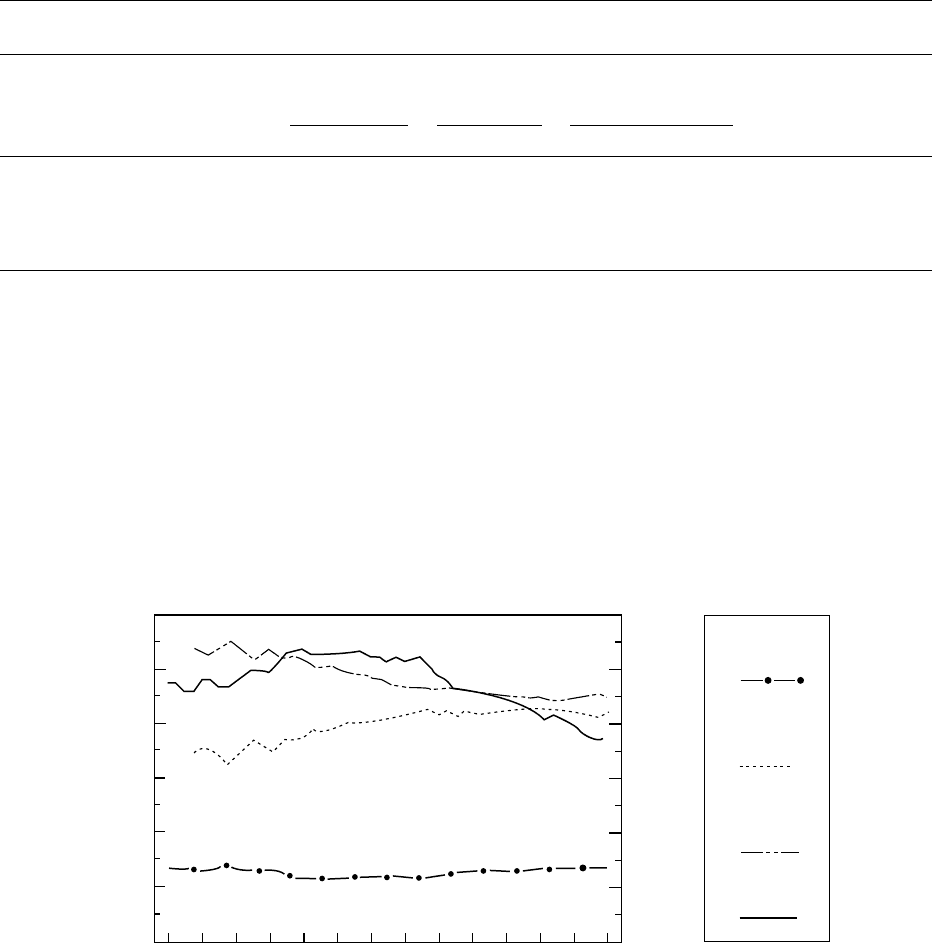

fig0002 Figure 2 High-performance liquid chromatographic (HPLC) chromatogram of red dye mixture separated by reverse-phase ion-pair

gradient elution. Conditions: solvent A ¼ 0.005 mol l

1

tetrabutylammonium bromide (TBAB) in methanol, solvent B ¼0.005 mol l

1

TBAB in 0.01 mol l

1

KH

2

PO

4

. Gradient elution profile: 50:50 to 100:0 (A:B) over 30 min linear, 10 min hold; solvent flow rate

¼0.4 ml min

1

; column: ODS 20 cm; detection wavelength: 520 nm. Peak identification: 1, amaranth; 2, allura red AC; 3,red

10B – nonpermitted analog of 4, Red 2 G; 5, ponceau 4R; 6, carmoisine; 7, erythrosine. Reproduced from Colours: Properties and

Determination of Synthetic Pigments, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK and Sadler

MJ (eds) 1993, Academic Press.

1566 COLORANTS (COLOURANTS)/Properties and Determinants of Synthetics Pigments

.0071 postrun qualitative and quantitative analysis

.

0072 liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry inter-

facing

Figure 2 shows a typical chromatogram of the separ-

ation of red food colors by gradient ion-pair HPLC. It

is possible to separate many of the UK-permitted and

several nonpermitted dyes on a single column system

by employing a combination of ion-pair gradient

elution and selective wavelength detection.

Diode Array Detection

0073 Diode array detectors have the ability to record the

entire spectral range of an eluting dye component

during an analysis. Absorbance data may be col-

lected simultaneously from 190 nm to as high as

800 nm and is achieved in real time. The diode

array detector allows the precise determination of

absorption maxima of adequately separated solutes

and facilitates positive peak identification and

peak purity analysis by rapid spectral scanning.

Chromatographic peaks may be identified by refer-

ence to spectral libraries of previously run reference

compounds. Multiple wavelength monitoring with

absorbance rationing may be used to characterize

and identify multicomponent dye mixtures in single

chromatographic runs. Chemometric techniques

similar to those used in direct spectrophotometry

have been used to characterize and quantify dye mix-

tures.

0074 These and other analogous methods and tech-

niques are also used for the detection and quantifica-

tion of nonpermitted dyes in foods.

See also: Adulteration of Foods: Detection; Amaranth;

Chromatography: Thin-layer Chromatography; High-

performance Liquid Chromatography; Gas

Chromatography; Supercritical Fluid Chromatography;

Colorants (Colourants): Properties and Determination of

Natural Pigments; Properties and Determinants of

Synthetic Pigments; Food Additives: Safety; Food

Labeling (Labelling): Applications; Food Safety; Mass

Spectrometry: Applications; Spectroscopy: Visible

Spectroscopy and Colorimetry

Further Reading

Damant A, Reynolds S and Macrae R (1989) The structural

identification of a secondary dye produced from the

reaction between sunset yellow and sodium meta-

bisulphite. Food Additives and Contaminants 6: 273–

282.

King RD (ed.) (1980) The determination of food colours.

In: Developments in Food Analysis Techniques 2, pp.

79–106. Barking: Applied Science Publishers.

Knowles ME, Gilbert J and McWeeny DJ (1974) Stability of

red food colours in the presence of nitrite in canned pork

luncheon meat. Journal of the Science of Food and Agri-

culture 25: 1239–1248.

Marmion DM (1984) Handbook of US Colorants for

Foods, Drugs, and Cosmetics, 2nd edn. New York:

John Wiley.

Marovatsanga L and Macrea R (1987) The determination

of added azo dye in soft drinks via its reduction prod-

ucts. Food Chemistry 24: 83–98.

Peters AT and Freeman HS (eds) (1995) Analytical Chemis-

try of Synthetic Colorants. Advances in Colour Chemistry

Series, vol. 2. London: Blackie Academic and Profes-

sional.

Reynolds SL, Scotter MJ and Wood R (1988) Determin-

ation of synthetic colouring matter in foodstuffs – col-

laborative trial. Journal of the Association of Public

Analysts 26: 7–25.

Trace Materials (Colours) Committee (1963) Analyst 88:

864.

Venkataraman K (ed.) (1977) The Analytical Chemistry of

Synthetic Dyes. New York: John Wiley.

Walford J (ed.) (1980) Developments in Food Colours 1.

Barking: Applied Science Publishers.

Walford J (ed.) (1984) Developments in Food Colours 2.

Barking: Elsevier Applied Science Publishers.

Colorimetry See Spectroscopy: Overview; Infrared and Raman; Near-infrared; Fluorescence; Atomic

Emission and Absorption; Nuclear Magnetic Resonance; Visible Spectroscopy and Colorimetry

Common Agricultural Policy See European Union: European Food Law Harmonization

COLORANTS (COLOURANTS)/Properties and Determinants of Synthetics Pigments 1567

COMMUNITY NUTRITION

J Cade, University of Leeds, Leeds, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

Community nutrition incorporates the study of nutri-

tion and the promotion of good health through food

and nutrient intake in populations. This article will

consider aspects of community nutrition relating to

dietary goals and recommendations for populations;

methods of assessing diet in population groups; and

promoting healthy eating at the community level.

0002 Community nutrition (public health nutrition) re-

quires a population approach. The community rather

than the individual is the focus of interest. This area

of nutrition focuses on the promotion of good health

and the primary prevention of diet-related illness. The

emphasis is on maintenance of health in the whole

population, although it will also include working

with high-risk groups and other subgroups within

the population. Community nutrition includes nutri-

tional surveillance; epidemiological studies of diet;

and also the development, implementation, and

evaluation of dietary recommendations and goals. A

community may be any group of individuals, for

example, the population of a town or country, or

the residents of an old people’s home.

Advice to the Community

0003 Dietary advice to the community has changed over

the years, depending on the nutrition-related diseases

of importance at the time and our understanding of

how they are caused. In the 1930s, for example, the

primary concern in Europe and North America was

the elimination of deficiency diseases. The concept of

a balanced diet was developed to try to provide the

minimum requirements of protein, vitamins, and

minerals. By the late 1950s, research suggested that

some chronic diseases could be related to overnutri-

tion and dieting to lose weight became popular. For

example, it was recommended that bread and potato

intake should be restricted to help avoid overweight.

However, by the 1980s, wholemeal bread and jacket

potatoes were being promoted as good sources of

dietary fiber.

0004 Recommended dietary allowances (RDAs) for

populations were first set in the 1930s and have been

revised at regular intervals. The current UK recom-

mendations were published in 1991, and are known as

dietary reference values (DRV). They include the ref-

erence nutrient intake (RNI) level which is the amount

of a nutrient (excluding energy) which is sufficient

for almost any individual. The RNI is 2 standard

deviations higher than the estimated average require-

ment and as such is higher than most people need. RNI

must be interpreted carefully when used in nutrition

education and is not intended to be used by individual

members of the public as a guide.

0005Dietary goals or guidelines, on the other hand, aim

to reduce the chances of developing chronic degenera-

tive diseases and are based on data from animal

experiments, metabolic studies, clinical trials, and epi-

demiological research. They give targets for the popu-

lation to aim at for some future time. The first set of

dietary goalswas published inSweden in 1968. The UK

has published its own goals. Nutrition goals were in-

cluded in the Health of the Nation White Paper (1992).

Further goals were included in the Department of

Health’s report in 1994 from the Committee on Med-

ical Aspects of Food Policy (COMA) on diet and car-

diovascular disease. The World Health Organization

(WHO) hasalso published population nutrient goals in

1990. These are recommended for use in all parts of the

world and have been expressed in absolute terms

rather than increases or decreases in existing nutrient

intake. The desirable change will then vary with the

population. For example, in some developing coun-

tries the goal for fat intake (lower limit) suggests the

need to increase average intakes slightly. Conversely,

for most industrialized countries a reduced fat intake is

desirable. Table 1 summarizes the COMA, Health of

the Nation, and WHO nutrient goals.

0006The recommendations are based on the best avail-

able evidence and may need to be changed in future.

For example, in the future they may need to address

optimal nutritional status.

Assessing Adequate Nutritional Status

0007In order to advise the community we need to know

what the community is already eating. The nutritional

status of the community can be defined as the presence

or absence of diet-related diseases and is related to the

health and well-being of the community. There is no

simple or single way to measure it so that information

has to be gathered from many sources.

Food and Nutrient Supply

0008National level Information on national food avail-

ability is collected annually by many governments in

the form of food balance sheets. The Food and Agri-

culture Organization (FAO) collects and publishes

1568 COMMUNITY NUTRITION

these statistics. It lists the total quantity of different

foods available for consumption in a country during a

specified time (usually one year). Data are limited

since there is no information available about sub-

groups of the population by region, ethnicity, age,

or socioeconomic level. Its accuracy is variable,

especially for areas with subsistence farming.

0009 Food balance sheets can be used to assess available

energy and nutrient intakes per capita. Comparing

changes over years can indicate trends towards or

away from national food security.

0010 Household level The National Food Survey carried

out by the UK Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and

Food (MAFF) assesses trends in food supplies and, by

inference, the food eaten. Nutrient intake can be calcu-

lated from these data. It records food purchased rather

than food eaten and does not distinguish between the

intakes of men, women, and children, nor does it in-

clude alcohol, candies (sweets), and soft drinks.

0011 As shown in Table 2, the National Food Survey is

particularly useful for assessing trends in food and

nutrient intake. In general, the food supply was con-

sistent with the amounts recommended to cover the

needs of most of the population.

0012 Itemized till receipts have also been shown to be

a good reflector of energy and fat intake in the

household in families which purchase the majority

of their food at supermarkets.

0013Individual level Assessing diet at the individual level

is usually done by survey. These use several different

methods such as a weighed intake, dietary recall or

record, or a food frequency questionnaire. Attempts

have been made to validate the resulting nutrient levels

by measuring biological markers. Surveys may look at

a representative sample of the population or a particu-

lar at-risk group. The UK government has commis-

sioned a series of regular surveys known as the

National Diet and Nutrition Surveys. The first one of

British adults was published in 1990. It aimed to re-

cruit a nationally representative sample of adults aged

16–64 living in private households in the UK to inform

food and health policy development and evaluation.

Subsequent surveys have studied preschool children,

the elderly, and young people. A second national

survey of adults is currently underway.

Anthropometric Measurements

0014Weight and height can be used to assess the level of

malnutrition or obesity by comparison with reference

data. Height can give evidence of past chronic malnu-

trition, whereas weight is more useful in assessing

recent nutritional experience. Overweight or obesity

tbl0001 Table 1 Comparison of dietary goals from the World Health Organization (WHO), Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy

(COMA), and Department of Health, Health of the Nation

WHO COMA Health of the Nation

goals by 2005

Dietary reference

value

a

Lower Upper

Total energy (MJ)

b

Maintain desirable body weight # Obesity –

Males to no more than 6% men 10.6

c

Females to no more than 8% women 8.1

Total fat 15 30 # to about 35% #by 12%, to no more than 35% 33 (35)

d

Saturated 0 10 #to no more than 10% # by 35%, to no more than 11% 10 (11)

d

Polyunsaturated 3 7 n-6 PUFA: no further

" n-3 PUFA: " from 0.1 to 0.2 g day

1

6 (6.5)

d

Cholesterol (mg day

1

) 0 300 No increase

Total carbohydrate (CHO) 55 75 50 47 (50)

d

Complex CHO 50 70 Increase 37 (39)

de

Free sugars 0 10 Increase from fruit and vegetables 10

f

(11)

d

Dietary fiber (g day

1

)27 40 18

g

Protein 10 15

Salt (g day

1

) 6 6 1.6

Alcohol

Units are percent total energy unless otherwise stated.

a

Values are population averages.

b

Energy intake to allow normal growth, pregnancy, lactation, work, activities and to maintain appropriate body reserves. Body mass index (kg m

2

)in

adults ¼ 20–22.

c

Estimated average requirement for men and women, aged 19–49 years, physical activity level 1.4.

d

Figures in brackets represent percentage of food energy.

e

Intrinsic and milk sugars and starch.

f

Nonstarch polysaccharides.

g

Nonmilk extrinsic sugars.

PUFA, polyunsaturated fatty acids.

COMMUNITY NUTRITION 1569

is most practically assessed using the body mass index

(weight in kg/height in m

2

).

Health Statistics

0015 Birth statistics such as neonatal, perinatal, or infant

mortality rates provide indirect information about

the nutritional status of a community, particularly

its disadvantaged groups. Death rates for diseases

which have a nutritional cause can also indicate

nutritional status in the community.

Qualitative Data

0016 Useful information about community food and nutri-

ent patterns can be obtained using qualitative meth-

odologies, such as informal interviews or focus group

discussions. If carefully carried out, these methods

can supplement data collected in the quantitative

methods described above and provide an indepth

understanding of issues such as motivations, food

choices, and particular food habits.

Success Level of General Advice

0017 In order to change a population’s diet, DRVs and

goals must have scientific credibility, political and

technical support, and be recognized as being neces-

sary and acceptable to the consumer. It may take

years to achieve the desirable change.

0018 Is the population meeting the DRVs for the UK popu-

lation? The results of three National Diet and Nutrition

Studies (NDNS) in the British population showing

the percentage who met the UK dietary goals are

presented in Table 3. Most subjects ate more total fat,

saturated fat, and refined sugars and less carbohydrate

and fiber than recommended. A comparison with a sub-

group of 15 000 women from the UK Women’s Cohort

Study shows that in this health-conscious group more

people were able to achieve the dietary goals than in the

earlier NDNS study of adult women.

0019People who consume diets which meet the nutrient

goals are more likely to eat cereals, wholemeal and

brown bread, skimmed or semiskimmed milk, poly-

unsaturated margarine, fruit, vegetables including

potatoes, low-fat meat, and nonfried fish. They also

eat less white bread, butter, margarine, whole milk,

high-fat cheese, eggs, fatty meat, and fried fish than

those who do not meet the goals. To achieve a par-

ticularly healthy diet independent predictive factors

have been found to be spending more money on food,

being a vegetarian, having a higher energy intake, and

a lower body mass index, and being older. Extra costs

of the food may make the cost of a diet which meets

the dietary goals too expensive for the elderly, un-

employed, and low-paid. It is worth noting, however,

that it is possible to consume a diet which meets the

dietary goals which is substantially cheaper than the

average cost of a diet which does not meet the goals.

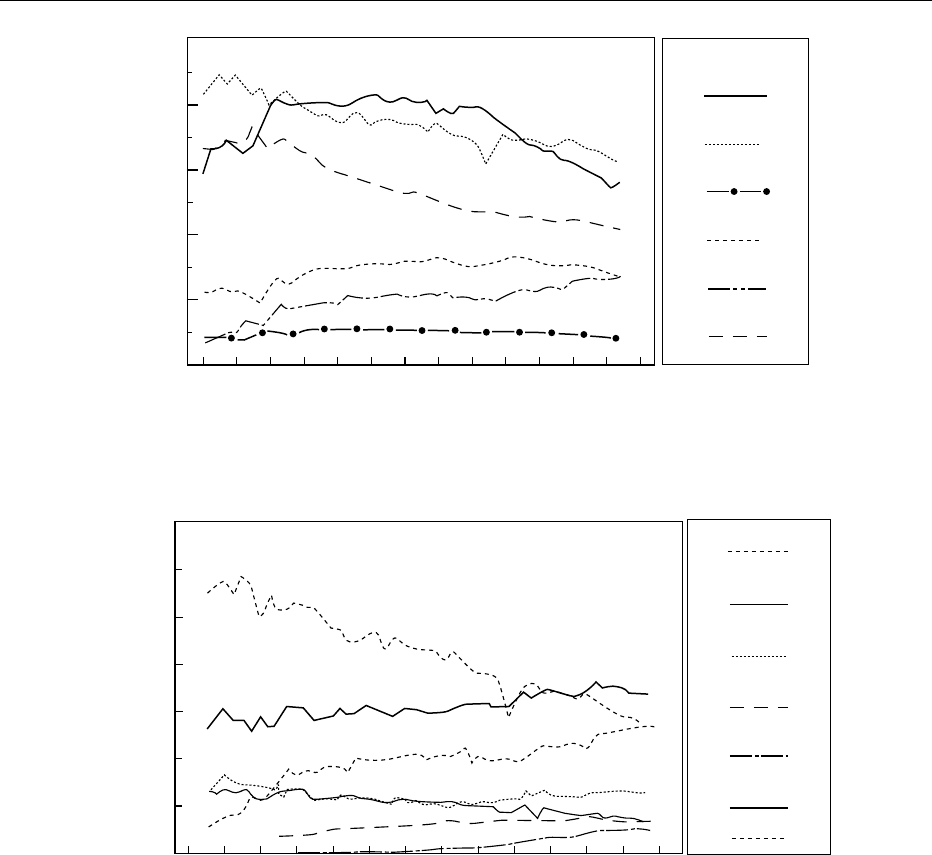

0020The National Food Survey can monitor progress

made by a population towards meeting the goals. It

has been analyzed for a 50-year period from 1940 to

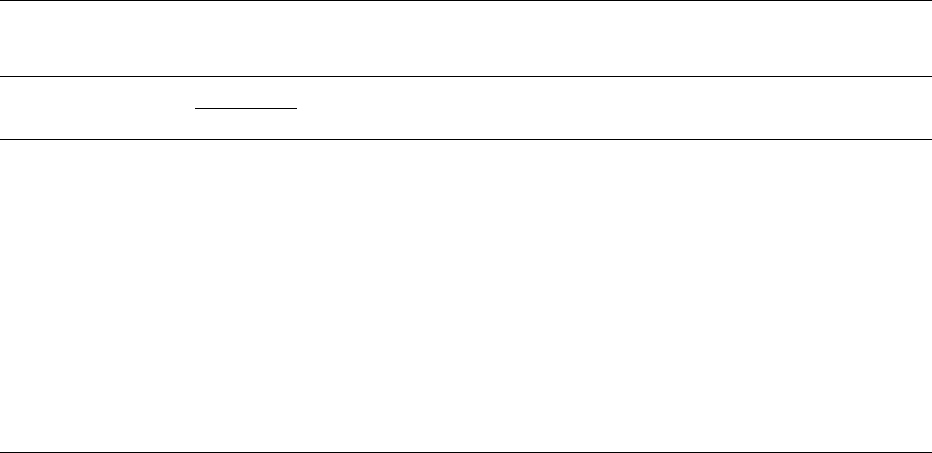

1992. There has been a decline in the percentage of

food energy from carbohydrate and an increase in the

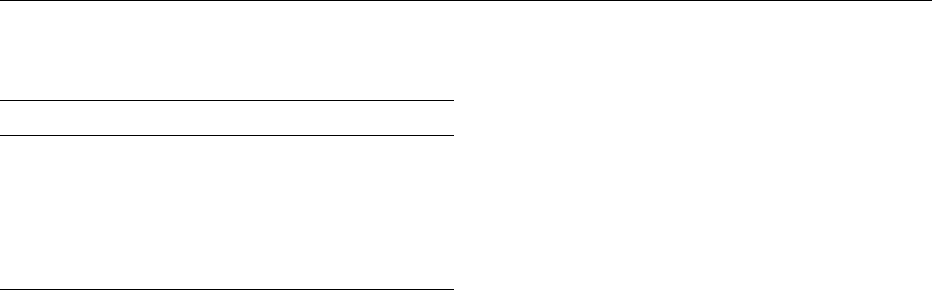

proportion from fat (Figure 1). There have been sub-

stantial changes in the types and quantities of foods

consumed over this period. Bread consumption has

fallen over this period from around 250 g day

1

in

1940 to 110 g day

1

in 1992 (Figure 2). Fresh potato

consumption has also declined, but fruit and other

vegetable consumption has increased from about

200 g day

1

to 300 g day

1

(Figure 3).

Community versus Individual Advice

0021Public health examines risk factors for disease in the

population as a whole and then designs prevention

strategies to reduce them. Meanwhile, the clinician

does the same for the individual patient.

0022Dietary goals for the population are based on iden-

tifying population intakes to maintain health. Health

is defined as a low rate of diet-related diseases. In

assessing whether a population is meeting the dietary

goal it is the entire range of nutrient intake which

matters. If the intake is normally distributed within

the population, then it can be summarized by the aver-

age intake of the population and its standard error.

0023Dietary goals require a population approach to

dietary change leading to a change in the average

intake. This will result in some individuals consuming

more and some less than the stated goal.

tbl0002 Table 2 Nutrient intake from the UK National Food Survey,

expressed as a percentage of recommended intakes current at

the time of the survey

195 8

a

1968

b

1978

b

1988

c

1998

d

Energy (kcal) 104 108 94 91 93

Protein (g) 100 127 121 123 147

Calcium (mg) 107 191 181 159 119

Iron (mg) 115 122 100 102 99

Thiamin (mg) 126 133 125 153 98

Riboflavin (mg) 108 129 138 123 149

Vitamin C (mg) 222 181 188 213 173

Recommended intakes:

a

British Medical Association (1950) Report of the Committee on Nutrition.

London: BMA.

b

Department of Health and Social Security (1969) Recommended Intakes of

Nutrients for the United Kingdom. London: HMSO.

c

Department of Health and Social Security (1979) Recommended Intakes of

Nutrients for the United Kingdom. London: HMSO.

d

Department of Health (1991) Dietary Reference Values for Food Energy and

Nutrients for the United Kingdom: Report of the Panel on Dietary Reference

Values, Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy. Report on Health and

Social Subjects 41. London: HMSO. Nutrient values from Ministry of

Agriculture, Fisheries and Food National Food Survey for years stated.

1570 COMMUNITY NUTRITION

Methods of Giving Advice to the

Community

0024 Much can be done to change a population’s diet.

Diets are chosen by individuals; government should

not enforce recommendations concerning diet

and health by restrictive legislation. Legislation

concerning the production and sale of food does

however affect a nation’s diet. An alternative

approach to change is to increase people’s knowledge

and awareness of food and its relationship to

health.

Health Promotion

0025Traditionally, nutrition education campaigns have

involved only one or two sections of the community

such as schools or the media. Success, if it was

measured at all, was limited. A more integrated ap-

proach is to involve as many groups of the community

% Food energy

Energy intake (kcal)

% Food energy

as fat

% Food energy

as protein

% Food energy

as carbohydrate

Energy intake

Year

60

50

40

30

20

10

0

1940 1944 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992

500

1000

1500

2000

2500

3000

fig0001 Figure 1 Trends in proportion of daily energy intake in the British diet derived from carbohydrate, fat, and protein (National Food

Survey 1940–1992). From Department of Health (1994) Nutritional Aspects of Cardiovascular Disease. Report on Health and Social Subjects

46. London: HMSO with permission.

tbl0003 Table 3 Percentage of population meeting dietary goals

Dietary goal NDNS

UK adults

(1986^87)

a

NDNS

1

1

/

2

^4

1

/

2

years

(1992^93)

b

NDNS

65 years þfree-living

(1994^95)

UK Women’s Cohort

(1995)

d

Health-consciouswomen

Men Women Boys Girls Men Women

Total fat 35% food energy 12 15 42

e

42

e

46 41

Saturated fat 15% food energy 11 12 38

f

38

f

59 48 43

g

Total carbohydrate > 50% energy 9 12 60

h

57

h

31 30 54

i

Refined sugars

k

< 10% food energy 12 13 30 36

Fiber > 25 g day

1

45 16 3

l

1

l

32

j

Note that the goals are not meant to refer to children – the preschool age children survey has been included for comparison.

a

Gregory J, Foster K, Tyler H and Wiseman M. (1990) The Dietary and Nutritional Survey of British Adults. London: HMSO.

b

Gregory JR, Collins DL, Davies PSW, Hughes JM and Clarke PC (1995) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: Children aged 1

1

/2 to 4

1

/2 years. London: HMSO.

c

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C et al. (1998) National Diet and Nutrition Survey: People Aged 65 Years and Over,vol.1.Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey.

London: Stationery Office.

d

Cade J, Upmeier H, Calvert C and Greenwood D (1999) Costs of a healthy diet: analysis from the UK Women’s Cohort Study. Public Health Nutrition 2:

505–512.

e

Less than 35% food energy from fat.

f

Less than 15% food energy from saturated fat.

g

0–10% total energy from saturated fatty acids.

h

Greater than or equal to 50% food energy from carbohydrate.

i

50–70% total carbohydrate.

j

27–40 g fiber.

k

Nonmilk extrinsic sugars.

l

20 g day

1

fiber.

NDNS, National Diet and Nutrition Studies.

COMMUNITY NUTRITION 1571

as possible and to use a variety of educational ap-

proaches. For example, Heart-Beat Wales is a health

promotion program which involves public education,

lay groups, schools, factories, retailers, and others.

Look After Your Heart is a multidisciplinary govern-

ment-backed campaign to reduce risk factors for cor-

onary heart disease. Evaluating the success of these

campaigns in terms of reduction of deaths from heart

disease is difficult. With regard to lowering fat intake,

general recommendations to the public without

individual dietary counseling are not very effective.

Despite educational campaigns to lower fat intake,

the level of saturated fat intake in Europe remains

considerably higher than desired.

0026Knowledge of the health risks of a food does not

inevitably lead to a change in its consumption. Why

people eat what they do is determined by a number of

factors; the health effects of a food may only have a

minor influence. Understanding these factors involves

the application of psychological models such as the

Theory of Planned Behavior or the Stages of Change

model. These models explore issues such as beliefs

about food and motivations for changing intakes.

Health education can change consumers’ purchasing

and eating habits. For example, the national pro-

motion of low-fat milk immediately increased its

consumption by 20%. Leaflets are often used, but

are ineffective with mass distribution.

Year

g day

−1

350

200

250

300

150

100

50

0

1940 1944 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992

Fresh potatoes

Fresh green

vegetables

Other fresh

vegetables

Canned

vegetables

Frozen

Total vegetables

Total fruit

excluding potatoes

vegetables

fig0003 Figure 3 Trends in consumption of vegetables and fruit. From Department of Health (1994) Nutritional Aspects of Cardiovascular Dis-

ease. Report on Health and Social Subjects 46. London: HMSO with permission.

Year

g day

−1

500

400

300

200

100

0

1940 1944 1948 1952 1956 1960 1964 1968 1972 1976 1980 1984 1988 1992

Vegetables

Fats and oils

Total liquid milk

Meats

Fruit

Bread and cereals

fig0002 Figure 2 Consumption of selected foods. From Department of Health (1994) Nutritional Aspects of Cardiovascular Disease. Report on

Health and Social Subjects 46. London: HMSO with permission.

1572 COMMUNITY NUTRITION

0027 The media can have an important influence on

choice of foods consumed. This has been demon-

strated recently by the concerns over new-variant

Creutzfelt–Jakob syndrome from infected beef and

unknown risks associated with genetically modified

foods. Media reports have raised awareness of these

issues and people have altered their food intake pat-

terns, although there is no evidence to suggest that

these changes have been detrimental to overall nutri-

tional status.

Health Professionals

0028 General practitioners are encouraged to provide

health promotion, but have little training in nutrition.

Patients are rarely referred to a dietitian; the practice

nurse often provides most of the advice. Dietary

advice provided by untrained members of the primary

health care team can be misleading. Community diet-

itians can provide group-based training and educa-

tion. The UK Nutrition Society is now recognizing a

group of nutritionists with experience in community

nutrition and awarding an accreditation in public

health nutrition.

0029 Most district health authorities have their own

food and health policies which are often limited to

measures within their own services. Potential con-

tributors to these policies are groups within the com-

munity such as local shopkeepers, industry, and trade

unions. Health action zones have been set up to

address inequalities in health in the community.

Some have incorporated nutrition and access to food

as priorities.

Food Labeling

0030 Food should be appropriately and comprehensibly

labeled to aid consumer choice. As yet, there is no

standard format for labels. The format for nutrition

labeling of foods and food claims is regulated by

Codex Alimentarius, or the food code. This is a global

reference point and deals with creating food standards.

Nutrition labeling is often difficult to understand. Sup-

plying the consumer with nutrition information

through the internet or in-store computer terminals

as well as highlighting the most important information

may solve the problem of demands for both more and

understandable information.

Web-based Resources

0031 Knowledge of nutrition and health can be acquired

from the internet. Recent figures suggest that around

16 million people have access to the internet in the UK.

This figure is increasing. It is important for sites to

be rated in terms of content, credibility, and usability.

A number of sites are on the fringe of conventional

nutrition and may be promoting information which is

unhelpful or confusing. NHS Direct has been set up to

provide telephone or web-based health advice and

includes a nutrition component.

Reaching Vulnerable Groups

0032Nutrition advice should take account of the special

needs of particular subgroups, who may be vulner-

able to malnutrition due to their physiological

requirements, their cultural traditions, or their

economic problems.

Babies and Young Children

0033The health professions have a role in promoting

breast-feeding and the preparation of culturally ac-

ceptable and appropriate weaning foods. In the UK,

in order to meet the current dietary goals the diet is

likely to increase in bulk and so reduce energy density.

It is important to maintain adequate energy intakes

by not changing babies on to low-fat milks too early.

Children in lone-parent families tend to have lower

carotene and vitamin C intakes than other children.

Growth monitoring, particularly in developing coun-

tries, can be used to detect growth faltering. Remedial

action can then be taken.

Adolescents

0034On the whole this group is adequately nourished.

There is some concern, however, at the low levels of

iron intake in teenage girls. Adolescents on slimming

diets may be at risk of low intakes of some micro-

nutrients. Appropriate nutrition education at school,

backed up with the provision of healthy school meals,

may help to encourage suitable nutritional habits in

this group.

Pregnancy and Lactation

0035Most pregnant and lactating women in the UK con-

sume an adequate diet. This is, however, a time when

women come into contact with health care services

and may be open to nutrition education. Young girls

and other women at risk of having a low-birth-weight

baby should have particular attention paid to their

dietary intake. Periconceptual folate supplements are

recommended to prevent neural tube defects.

Elderly

0036The current dietary goals are appropriate for the

elderly. Energy intakes tend to decrease with increas-

ing age and there is a need for the elderly to consume

diets with an increased nutrient density. Health

professionals and other carers need to be aware of

the potential for the elderly to be consuming an

inadequate diet. The NDNS for people aged 65 and

over found that intakes of vitamin D, Mg, K, and Cu

COMMUNITY NUTRITION 1573

were low. A substantial proportion of people living in

institutions had low biochemical status indices for

vitamin C, Fe, and folate.

Low-income Groups

0037 Families on a low income and those living in tempor-

ary accommodation may find it difficult to eat a diet

which meets the recommendations. There is particu-

lar concern for people living in socially disadvantaged

areas since there is a greater risk of birth abnormal-

ities and a higher incidence of diseases such as coron-

ary heart disease and cancer in the adult population.

Ethnic Groups

0038 Many aspects of different ethnic dietary patterns will

promote health, such as high fruit or vegetable intakes.

Some ethnic groups, however, also consume diets

which are characterized by a high fat intake and

certain groups have a higher prevalence of obesity,

diabetes, and coronary heart disease. In some com-

munities women and children may be at risk of

vitamin D deficiency. Culturally acceptable nutrition

education needs to be in a form that can be under-

stood by the whole community. Personal intervention

by a trained member of the local community may give

the best results.

See also: Adolescents; Dietary Reference Values;

Elderly: Nutritional Status; Epidemiology; Ethnic

Foods; Food Labeling (Labelling): Applications;

Infants: Nutritional Requirements; Lactation: Human

Milk: Composition and Nutritional Value; Pregnancy:

Metabolic Adaptations and Nutritional Requirements

Further Reading

Committee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy (1994) Nu-

tritional Aspects of Cardiovascular Disease. Report on

Health and Social Subjects 46. London: HMSO.

Department of Health (1991) Dietary Reference Values for

Food Energy and Nutrients for the United Kingdom:

Report of the Panel on Dietary Reference Values, Com-

mittee on Medical Aspects of Food Policy. Report on

Health and Social Subjects 41. London: HMSO.

Department of Health (1992) The Health of the Nation: A

Strategy for Health in England. London: HMSO.

Finch S, Doyle W, Lowe C et al. (1998) National Diet and

Nutrition Survey: People aged 65 years and over, vol. 1.

Report of the Diet and Nutrition Survey. London:

Stationery Office.

Gregory J, Foster K, Tyler H and Wiseman M (1990) The

Dietary and Nutritional Survey of British Adults.

London: HMSO.

Gregory JR, Collins DL, Davies PSW, Hughes JM and

Clarke PC (1995) National Diet and Nutrition Survey:

Children aged 1½ to 4½ years. London: HMSO.

Ministry of Agriculture, Fisheries and Food (1999) National

Food Survey 1998. London: Stationery Office.

World Health Organization (1990) Diet, Nutrition and the

Prevention of Chronic Diseases. Technical Report Series

797. Geneva: World Health Organization.

CONDENSED MILK

H J Hess, Nestec Ltd, Vevey, Switzerland

This article is reproduced from Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Copyright 1993, Academic Press.

Background

0001 Industrial production for both sweetened and

unsweetened condensed milk started around the

middle of the nineteenth century. However at the

beginning of the nineteenth century, food scientists

in Europe, mainly in France and England, and in the

USA had been working on the possibility of preserv-

ing milk as a concentrated liquid. Both products have

their industrial roots in the USA.

0002 The first sweetened condensed milk in hermetically

sealed cans was manufactured and sold in 1856 by

Gail Borden in the USA. The business grew rapidly

and spread to Europe by 1866 where a sweetened

condensed milk factory was set up in Cham, Switzer-

land, by Charles A. Page, a US consul assigned to the

country. The rapid success of this Swiss-based com-

pany within Europe led eventually to an expansion

of its manufacturing facilities in the USA. This organ-

ization, registered as the Anglo-Swiss Condensed

Milk Company, sold its US interest in 1902 to a

company established and registered at the end

of the nineteenth century as the Borden Condensed

Milk Company. In 1904, the remaining European

interests of the Anglo-Swiss Company merged with

Henry Nestle

´

, of Vevey, Switzerland, who also

manufactured this product. The new company was

called the Nestle

´

-Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk

Company.

0003Until the early 1880s, unsweetened condensed milk

was also produced and was sold open in the market

1574 CONDENSED MILK

due to the lack of knowledge and success of long-life

preservation at that time.

0004 The basic process for preservation of unsweetened

condensed milk by heat sterilization was conceived by

John B. Meyenberg in 1882, a Swiss citizen, and an

employee of the Anglo-Swiss Condensed Milk Com-

pany. The idea of preserving milk without the add-

ition of sugar was made possible by his invention of a

revolving sterilizer working with steam under pres-

sure. Lacking sufficient support from his company

to continue his work, he migrated, in 1884, to the

USA and also obtained a patent for his invention in

that country. In 1885, Mr Meyenberg was cofounder

of the Helvetia Milk Condensing Company in the

State of Illinois, and during the same year, he achieved

the first successful manufacture of unsweetened

condensed milk. The name of this product was

changed to evaporated milk for a clearer distinction

from sweetened condensed milk, a situation that

prevails today.

0005 The initial phase of commercial production of

both products was hampered by various problems

and quality defects. Only at the beginning of the

twentieth century were constant quality standards

reached.

Definition of Products

Sweetened Condensed Milk

0006 Sweetened condensed milk is made by the addition

of sugar to whole milk and the removal of water

from the milk to about one-half of its original

volume. The product is canned or packaged in

other containers without sterilization, with the

sugar acting as a preservative. International standards

prescribe:

.

0007 a minimum milk fat content of 8%;

.

0008 a minimum milk solids content of 28%.

The minimum sugar content is often not specified

precisely but should be sufficient to avoid spoilage.

0009 Permitted stabilizers are usually specified as

sodium, potassium, and calcium salts of:

.

0010 hydrochloric acid;

.

0011 citric acid;

.

0012 carbonic acid;

.

0013 orthophosphoric acid;

.

0014 polyphosphoric acid.

0015 The name of the product may be:

.

0016 sweetened condensed milk;

.

0017 sweetened condensed whole milk; or

.

0018 sweetened full-cream condensed milk.

0019Legislation in some countries requires a somewhat

higher milk solids and fat content, usually 9% milk

fat and 31% total milk solids. However, there are also

provisions for skimmed sweetened condensed milk

with a milk solids content up to 24% and low-fat

compositions, in principle, of 4% fat and 24% total

milk solids.

0020Frequently, this product is fortified by the addition

of vitamins, mainly A, D

3

, and B

1

.(See Food Fortifi-

cation.)

Evaporated Milk

0021Evaporated milk is made by removal or evaporation

of water from milk but without the addition of sugar

or any other preservative material. The canned

product is heat-sterilized at 118–122

C for several

minutes. The product also may be packed in any

other sterilizable container.

0022International standards prescribe:

.

0023a minimum milk fat content of 7.5%;

.

0024a minimum milk solids content of 25.0%.

0025Permitted stabilizers are usually specified as

sodium, potassium, and calcium salts of:

.

0026hydrochloric acid;

.

0027citric acid;

.

0028carbonic acid;

.

0029orthophosphoric acid;

.

0030polyphosphoric acid.

In addition, some legislation permits the addition of

carrageenan up to 150 p.p.m.

0031The main name of the product is:

.

0032evaporated milk;

.

0033evaporated full-cream milk; or

.

0034unsweetened condensed full-cream milk.

0035Legislation in some countries requires a somewhat

higher fat and milk solids content, up to 9 and 31%,

respectively. However, there are also provisions for

either skimmed or low-fat evaporated milks:

.

0036skimmed evaporated milk with a minimum of 20%

milk solids;

.

0037low-fat evaporated milks, 4 or even 2% milk fat

and a milk solids content of 20–24%.

0038Fortification with vitamins of either or both A or

D

3

is common practice.

Recombined Milk Products

0039Sweetened condensed milk and evaporated milk are

often recombined in countries outside the traditional

dairy belt. (See Recombined and Filled Milks.)

0040For recombining, imported skim milk powder and

anhydrous milk fat are used to make up the milk

CONDENSED MILK 1575