Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

are common findings. The disease is characterized by

bleeding from inflamed colonic mucosa, tenesmus,

mucus discharge, and abdominal pain. The majority

of patients remain asymptomatic. Diversion colitis

is likely caused by a deficiency of SCFA, which serve

as luminal nutrients for colonocytes. The differen-

tial diagnosis for diversion colitis includes acute

self-limited colitis, antibiotic-associated colitis, and

preexisting UC or CD. The definitive treatment of

diversion colitis is restoration of intestinal continuity.

Surveillance for cancer in the diverted segment is not

necessary, provided that the underlying condition for

which the operation was performed has no malignant

potential. Randomized controlled studies have not

confirmed a beneficial role of SCFA in the treatment

of diversion colitis, a peculiar finding. These studies

were hampered by the small sample size and short

duration of treatment. In those with preexisting IBD,

SCFA combined with antiinflammatory drugs may be

effective.

0025 A low-residue diet is recommended during acute

phases of colitis, the idea being that insoluble par-

ticles irritate the bowel and make diarrhea worse.

Recently, however, the rarity of UC in developing

countries, together with the ability of dietary fibre

to affect colonic function and its bacterial content,

has suggested that a low intake of fiber might be a

factor in causing UC. A high-fiber diet can be pre-

scribed for patients during quiescent phases of

disease.

0026 Initial studies suggested a reduced postoperative

morbidity and mortality in patients with UC receiving

TPN. However, parenteral nutrition is not an effect-

ive primary therapy for UC. Retrospective studies

have failed to provide evidence for the use of TPN

in inducing remission of UC. Moreover, five prospect-

ive studies investigating the use of TPN in inducing

remission in UC failed to show any benefit for TPN

versus control groups. In all five studies, there was a

mean 37% initial response rate and only a 12% sus-

tained response rate. TPN appears to have little influ-

ence on refractory patients with active disease, and

rarely can TPN avert colectomy. TPN can be useful to

prepare the malnourished patient for surgery as well

as providing postoperative nutritional support. There

have been relatively few studies looking at the use of

elemental diets in UC. It is generally considered that

enteral nutrition is not effective in achieving remis-

sion in active ulcerative colitis.

0027 The role of diet and nutrition in patients with IBD

remains controversial. By applying an orderly and

comprehensive approach to management, many of

the complications of IBD can be contained or pre-

vented. While the role of diet continues to evolve, its

efficacy in the management of IBD is undisputed.

Diet and Nutrition in Irritable Bowel

Syndrome

0028Irritable bowel syndrome (IBS) is defined as a func-

tional bowel disorder in which abdominal pain is

associated with defecation or a change in bowel

habit, with features of disordered defecation and dis-

tention. Criteria for IBS have been formalized in the

Rome Criteria (Table 6). IBS is a disorder that can be

diagnosed positively on the basis of a series of symp-

tom criteria and limited evaluation to exclude organic

disease. The incidence of IBS has been estimated to be

1% per year. Prevalence data estimate a range of 2.9–

20%. Patients have been divided into subgroups

based on the predominant symptom. Symptom sub-

groups include constipation-predominant IBS, diar-

rhea-predominant IBS, and IBS with alternating

bowel movements. The prevalence of IBS is lower in

the elderly and higher in female patients. Only 10–

25% of patients with IBS seek medical care. The

economic impact in the USA is estimated at $25 bil-

lion annually. IBS accounts for 2.4–3.5 million phys-

ician visits in the USA annually, making it the most

common diagnosis in gastroenterologists’ practice

(12% of primary care visits, 28% of all gastroenter-

ologist’s patients).

Pathophysiology

0029There is no single physiological mechanism respon-

sible for symptoms of IBS. IBS is considered a bio-

psychosocial disorder resulting from a combination

of psychosocial factors, altered motility and transit,

and increased sensitivity of the intestine or colon

(Table 7). It has been hypothesized that altered per-

ipheral functioning of visceral afferents and the cen-

tral processing of afferent information are important

in the altered somatovisceral sensation and motor

dysfunction in patients with IBS. It has been postu-

lated that persistent neuroimmune interactions after

tbl0006Table 6 Criteria for the diagnosis of IBS

Manning criteria Pain relieved by defecation

More frequent stools at the onset of pain

Looser stools at the onset of pain

Visible abdominal distention

Passage of mucus

Sensation of incomplete evacuation

Rome II criteria At least 12 weeks or more, which need

not be consecutive in the previous

12 months of abdominal pain or

discomfort with two of three features:

relief with defecation, onset associated

with a change in the frequency of stool,

onset associated with a change in

the appearance of stool

1536 COLON/Diseases and Disorders

infectious gastroenteritis resulting in continuing sen-

sorimotor dysfunction might be a cause of IBS. Infec-

tious diarrhea precedes the onset of IBS symptoms in

7–30% of patients.

0030 In some patients, carbohydrate intolerance may

contribute to the symptoms of IBS. Data suggest

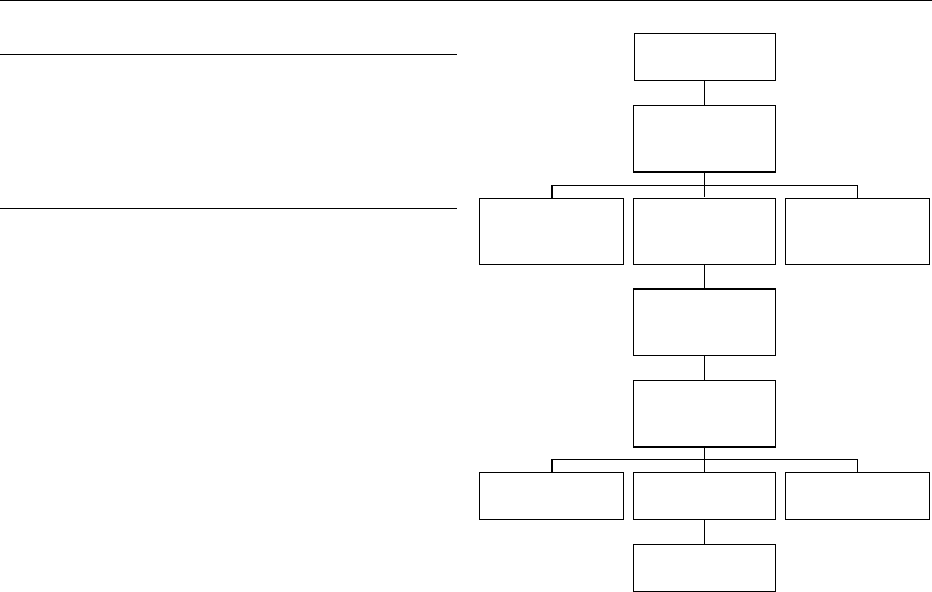

that food allergens may play a role in IBS (Figure 1).

Symptoms often improve with dietary exclusion.

Stress and emotions affect gastrointestinal function

and cause symptoms in patients with IBS. Psychologic

symptoms that are more common in patients with IBS

include somatization, anxiety, hostility, phobia, and

paranoia.

Diagnosis

0031 Many patients’ symptoms fluctuate over time. Re-

gardless, IBS is a ‘safe’ diagnosis. Patients with IBS

have a benign course without any risk of developing

organic disease. The diagnosis of IBS first involves a

careful assessment of the patient’s symptoms. Man-

ning or Rome criteria can be used to identify patients

with IBS. A thorough physical examination and a

limited series of initial investigation are needed to

exclude organic structural, metabolic, or infectious

diseases. Investigations include hematology and

chemistry tests, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, stool

examination for occult blood, ova, and parasites, and

possible flexible sigmoidoscopy.

Food Intolerance

0032 Data from dietary elimination and food challenge

studies support the role of diet in the pathogenesis

of a subgroup of IBS patients. The term ‘food intoler-

ance’ encompasses nonimmunologically mediated

adverse reactions to food, which resolve following

dietary elimination and are reproduced by food chal-

lenge. Food allergy or hypersensitivity is used to

describe conditions in which an immunological mech-

anism may be demonstrable. Food aversion is a psy-

chological avoidance response. A prevalence for food

intolerance of 5% has been reported in the general

population. Food hypersensitivity is a common per-

ception amongst IBS patients with 20–65% attribut-

ing their symptoms to adverse food reactions. The

effect of dietary exclusion followed by food challenge

has been investigated in several trials. Food intoler-

ances have been recognized in 6–58% of cases, with

milk, wheat, and eggs being the most commonly

implicated foods. In the largest study, the effect of

an exclusion diet was evaluated in 200 IBS patients.

Symptomatic improvement was reported in 91/189

(48%) patients and was maintained for a mean of

14.7 months. Following dietary challenge, 73/91

(80.2%) of responders identified one or more food

intolerances. The investigators conclude that a por-

tion of IBS patients may benefit from dietary

manipulation.

0033The bowel mucosa acts as a physical barrier to a

variety of intraluminal dietary and microbial anti-

gens. Under normal physiological conditions intact

food antigens can penetrate the mucosal barrier via

transcellular or paracellular routes. The mechanism

by which the mucosal immune system maintains a

state of immunological tolerance is not clear. Studies

demonstrating a positive response to elimination diets

support the role of a food hypersensitivity reaction in

IBS. An immune-mediated food hypersensitivity re-

sponse involving IgE and IgG antibodies has been

postulated as the underlying mechanism in patients

with IBS.

0034While there is no clear evidence to suggest that IBS

is an infective condition, up to 30% of patients de-

velop symptoms after an episode of gastroenteritis.

Food antigen

challenge

Mucosal antigen

processing

(B cells, T cells)

IgG

response

IgE

immediate and

delayed reaction

Other non-IgE

mediated

Mast cell

sensitization

degranulation

Release of

mediators

(histamine etc)

Abnormal mucosal

sensitivity

Abnormal

secretory response

Abnormal

motility

Irritable bowel

syndrome

fig0001Figure 1 Pathogenesis of food hypersensitivity in IBS.

tbl0007 Table 7 Pathophysiology of IBS

Biopsychosocial disorder

Abnormal motility

Heightened visceral perception

Psychologic distress

Intraluminal factors – lactose, bile acids, short-chain fatty acids,

food allergen

Postinfectious alteration of gut function

COLON/Diseases and Disorders 1537

Infective and inflammatory conditions of the bowel

cause an increased mucosal permeability, thereby ex-

posing the immune system to an increased load of

dietary and microbial antigens. The production of a

variety of proinflammatory and immunomodulatory

cytokines may serve to prime the mucosal and sub-

mucosal immune system establishing a hypersensitiv-

ity response. Altered bowel flora has been reported in

patients with IBS. Restoration of bowel flora whether

by dietary manipulation or through the use of pro-

biotics has been suggested as a treatment for IBS.

Treatment

0035 The dietary treatment of patients with IBS has

centered around bran supplementation, manipulating

the dietary fiber content of the diet and the identifica-

tion of food intolerance. There are currently no

evidence-based guidelines on how dietitians should

treat patients with IBS. An in-depth assessment of a

patient’s dietary intake is essential prior to any thera-

peutic dietetic intervention. A history regarding the

onset of symptoms in relation to any dietary changes

is often useful. Dietary intervention needs to be indi-

vidualized with respect to the patient’s symptoms.

Of the eight studies evaluated, five identified food

intolerance as a major contributor to symptoms.

There are no randomized control trials in this area

primarily due to the impracticality of constructing a

trial design. In all trials, the methods used to assess

the effect of intolerance to suspect foods on symp-

toms varied. In summary, seven studies mentioned

dairy products, six coffee, and five wheat. Others

cite eggs, corn, potatoes, onions, fruits, and vege-

tables. In the majority of the studies, the patients

with diarrhea responded favorably to an exclusion

diet compared to other subtypes of IBS. The recom-

mendation that elimination diets control the

symptoms of IBS is based on poorly designed and

incomplete trials. The absence of any objective symp-

tom assessment in the trials raises questions about

their validity.

0036 The mainstay of dietary therapy for IBS has

centered around the manipulation of dietary fiber.

Rees et al. conducted a critical review of clinical trials

examining the effect of dietary fiber on symptoms in

patients with IBS. In the review, it was shown that six

out of eight investigations detected no significant dif-

ference in most of the symptoms of IBS between fiber

and placebo. In the eight trials, the amount of supple-

ment varied, the form in which the fiber was adminis-

tered differed, and the type of fiber supplement was

different. The literature does not support any benefi-

cial effects of increasing insoluble nonstarch polysac-

charides in IBS patients. Increasing insoluble wheat

products in the diet may be of some benefit in patients

with predominantly symptoms of constipation. Many

patients complain of bloating with higher doses of

fiber. Bran is reported to be no better than placebo

in relief of overall IBS symptoms and may be worse

than a normal diet for symptoms of IBS caused by

intraluminal distention. Fiber may induce bloating by

increasing residue loading and bacterial fermentation

without accelerating the onward movement of the

increased residue. Nonetheless, there appears to be

significant improvement in constipation if sufficient

quantities of fiber (20–30 g day

1

) are consumed. As

a result, it is common practice to start with a low

dose, increasing gradually, and abandoning high

levels of supplementation (> 30 g day

1

) if patients

experience worsening of symptoms. Therefore, it can

be concluded that fiber may have a role in treating

constipation with a minimal role in the relief of

abdominal pain and diarrhea.

0037The role of carbohydrate and sorbitol is not rou-

tinely considered in the management of IBS. Trials

cannot confirm a true malabsorption of carbo-

hydrates in patients with IBS. Nonetheless, studies

have shown that patients with IBS develop symptoms

after being exposed to a sorbitol diet, when compared

to controls. One-third of those with IBS reported

lactose intolerance on a subjective basis. The percent-

age of lactose maldigesters in patients with IBS is

the same as in healthy subjects, but the number of

subjects reporting lactose intolerance is higher (60%

compared to 27%). There is a strong relationship

between subjective lactose intolerance and IBS. The

inconclusive findings of, and association of, lactose

intolerance and IBS can be explained by poorly

designed studies. Lactose intolerance has been associ-

ated with GI symptoms, and whether this is due to

lactase deficiency or increased sensitivity cannot be

answered.

0038In summary, the goal of dietary manipulation in

patients with IBS is to help patients control their

symptoms. Dietary assessment is essential for all

patients with determination of their present dietary

intake. Any unusual or abnormal eating practices

need to be assessed in relation to the patient’s symp-

toms. It is important to obtain a detailed history of

the onset of symptoms and their relation to the indi-

vidual’s eating pattern. Exclusion diets should be tried

only when patients complain of multiple food intoler-

ance, and single food avoidance has not helped

control symptoms. Patients taking large quantities

of sorbitol should be discouraged of such practice,

especially if their symptoms are predominantly pain

and diarrhea. A milk-free or lactose-free diet should

be tried in those patients in whom dairy products are

associated with symptoms. Patients continuing on

this diet should take calcium supplements. A trial of

1538 COLON/Diseases and Disorders

a wheat-free diet may be helpful. If a patient’s pre-

dominant symptom is constipation, an assessment of

fluid intake should be undertaken. Regular meal pat-

terns should be encouraged in all patients. Finally, an

assessment of the type and quantity of nonstarch

polysaccharides consumed should be made. The add-

ition of bran and insoluble fibers should be dis-

couraged, unless the individual feels this is of direct

benefit in symptom control. More emphasis should be

placed on increasing the proportion of foods contain-

ing a higher concentration of soluble nonstarch

polysaccharides.

Diet and Nutrition in Diverticular Disease

0039 Diverticular disease is a term encompassing diverticu-

losis and diverticulitis. Diverticulosis occurs in at

least one person in two over the age of 50 years.

The prevalence of diverticular disease is age-

dependent, increasing from less than 5% at age 40,

to 30% by age 60, to 65% by age 85. A male prepon-

derance was noted in early series, but more recent

studies have suggested either an equal distribution

or a female preponderance. There are geographic

variations in both the prevalence and pattern of di-

verticulosis. Westernized nations have prevalence

rates of 5–45%, depending upon the method of diag-

nosis and age of the population. Diverticular disease

in these countries is predominantly left-sided. The

findings are markedly different in Africa and Asia,

where the prevalence is less than 0.2%, and diverticu-

losis is usually right-sided. Diverticulosis or diverticu-

lar disease of the colon is due to pseudodiverticula in

that the wall of the diverticulum is not a full-thickness

colonic wall, but rather outpouchings of colonic

mucosa through points of weakness in the colonic

wall where the blood vessels penetrate the muscularis

propria. These diverticula are prone to infection or

‘diverticulitis’ presumably because they trap feces

with bacteria. Among all patients with diverticulosis,

70% remain asymptomatic, 15–25% develop

diverticulitis, and 5–15% develop some form of

diverticular bleeding. Diverticulitis represents micro-

or macroscopic perforation of a diverticulum. The

primary process is thought to be erosion of the diver-

ticular wall by increased intraluminal pressure or

inspissated food particles; inflammation and focal

necrosis ensue, resulting in perforation. If the infec-

tion spreads beyond the confines of the diverticula in

the colonic wall, an abscess is formed. Patients pre-

sent with increasing left lower quadrant pain and

fever, often with constipation and lower abdominal

obstructive symptoms such as bloating and disten-

tion. Some patients with severe obstructive symptoms

may actually describe nausea or vomiting. This can

occur with or without abscess formation. The diag-

nosis of acute diverticulitis is often made on the basis

of the history and the physical examination. On

physical examination, the patient often has localized

tenderness in the left lower quadrant and, with severe

infection and an abscess, may have rebound tender-

ness in the left lower quadrant. A palpable mass is

often identifiable where the sigmoid colon (the most

common site of diverticulitis) is infected. Computed

tomographı

¨

c (CT) scanning has become the optimal

method of investigation in patients suspected of

having acute diverticulitis, being employed for diag-

nosis, assessment of severity, therapeutic interven-

tion, and quantification of resolution of the disease.

CT scan may be helpful in outlining the colon and

identifying an abscess, and is preferable to barium

enema for diagnosis in patients with acute illness.

After resolution of an episode of acute diverticulitis,

the colon requires full evaluation by colonoscopy,

barium enema, or both to establish the extent of

disease and to rule out coexistent lesions, such as

polyps or carcinoma.

Etiology

0040It has been speculated that low dietary fiber predis-

poses to the development of diverticular disease. In

one study, Burkitt and Painter demonstrated that indi-

viduals in the UK eating a Western diet low in fiber had

colonic transit times of 80 h and a mean stool weight of

110 g day

1

. In comparison, Ugandans eating very

high fiber diets had transit times of 34 h and greater

stool weights (> 450 g day

1

). The longer transit times

and smaller stool volumes were felt to contribute to the

development of diverticular disease through the in-

crease in intraluminal pressures that predispose to

diverticular herniation. The etiology of diverticular

disease is unknown. The leading theory suggests that

altered colonic motility plays a major role in the devel-

opment of diverticula. Higher resting, postprandial

and neostigmine stimulated pressures in diverticular

patients suggest that a delay in transport with augmen-

tation of water reabsorption could cause excessively

high pressures forcing mucosa to herniate.

0041A recent report that evaluated a cohort of over

47 000 men provided strong evidence for the role of

dietary fiber. After adjustment for age, energy-

adjusted total fat intake, and physical activity, total

dietary fiber intake was noted to be inversely associ-

ated with the risk of symptomatic diverticular disease.

The relative risk was 0.58 for men in the highest quin-

tile compared to those in the lowest quintile for fiber

intake. The observation that diverticular disease is less

common in vegetarians than nonvegetarians is also

compatible with a role for dietary fiber, since vege-

tables and fruits are important sources of fiber.

COLON/Diseases and Disorders 1539

0042 Other dietary factors that might contribute to

the pathogenesis of diverticular disease have been

examined. There is no substantially increased risk

associated with smoking, caffeine, or alcohol. How-

ever, an association has been noted between obesity

in men under 40 years and acute diverticulitis. This

finding is compatible with observations that the risk

of symptomatic diverticular disease is particularly

increased (relative risk 2.35–3.32, 95% confidence

interval) by a diet characterized by a high intake of

total fat or red meat and a low intake of dietary fiber.

Treatment

0043 The treatment of diverticular disease can be divided

into prevention of diverticulosis, uncomplicated di-

verticulosis, and complicated diverticulosis (Table 8).

0044 The mainstay of treatment for preventing diver-

ticulosis is a diet high in fruit and vegetable fiber.

This suggestion is based on observations that low-

fiber diets are associated with colonic diverticulosis.

Recommendations are also based on results from the

Health Professionals Follow-up Study, which showed

an inverse association between insoluble dietary fiber

intake and the risk of developing symptomatic diver-

ticular disease. In particular, the greatest reduced risk

was in those consuming a diet high in fruit and

vegetable fiber, with an average consumption of 32 g

day

1

.

0045 The management of uncomplicated diverticulosis

involves a diet high in fruit and vegetable fiber. The

majority of patients with diverticular disease will

remain asymptomatic. Therefore, this group of pa-

tients consists of the largest treatment group. There

are no data to support any therapeutic recommenda-

tions in this group of patients. There have been mul-

tiple uncontrolled studies demonstrating the effect of

fiber in patients with diverticulosis, but the lack of

a placebo group complicates the results. Other well-

conducted studies have reported conflicting results

regarding the use of fiber. Despite conflicting data, it

appears safe to recommend a diet high in fiber for

patients with uncomplicated diverticular disease.

0046 Complicated diverticulosis includes diverticulitis

and hemorrhage (Table 9). Patients with mild diver-

ticulitis can be treated as outpatients with broad-

spectrum oral antibiotics with activity against anaer-

obes and Gram-negative rods. Patients should be on

the alert for symptoms of increasing pain, fever, or

inability to tolerate oral foods. Such patients are

treated with a clear liquid diet. Patients admitted to

hospital with more severe diverticulitis should be

placed on bowel rest with clear liquids or nothing

by mouth. Intravenous fluid therapy is required. In

addition, intravenous antibiotics should be initiated

to target colonic anaerobes and Gram-negative rods.

Improvement is expected within 2–4 days, at which

point the diet can be advanced. In patients hospital-

ized with acute diverticulitis, 15–30% will require

surgery. After resolution of acute diverticulitis, the

likelihood of recurrence and the role of elective surgi-

cal resection are important to prevent further attacks.

The risk of recurrence after an acute attack ranges

from 7 to 62%. Recurrent attacks are less likely to

respond to medical and diet therapy and often require

emergent surgery. Therefore, elective surgery is often

recommended after two attacks of acute diverticu-

litis.

Diet and Nutrition in Infectious Colitis

0047Infectious or noninfectious causes may be responsible

for acute diarrhea, and in selected patients, both

can occur simultaneously. Noninfectious causes

of diarrhea include drugs, food allergies, primary

gastrointestinal diseases such as inflammatory bowel

disease, and other disease states such as thyrotoxico-

sis and the carcinoid syndrome (Table 10). A variety

of infectious diseases cause acute diarrhea. Diarrheal

diseases represent the second most common cause of

death worldwide and the leading cause of childhood

death. Diarrhea results in 300–400 deaths per year in

children in the USA, approximately 200 000 hospital-

izations, 1.5 million outpatient visits, and more than

one billion dollars in direct medical costs. Acute diar-

rheal disease is generally defined as three loose stools

(or two loose stools with abdominal symptoms) or

more than 250 g of stool per day for up to 7 days.

When diarrhea lasts for 14 days, it can be considered

persistent; the term chronic generally refers to

diarrhea that lasts for at least a month. It is useful to

categorize infectious diarrheal diseases by the portion

tbl0008 Table 8 Management of patients with diverticulosis

Prevention High-fiber diet

Uncomplicated High-fiber diet

No antispasmodics

No antibiotics

Complicated Broad-spectrum antibiotcs

Bowel rest

Surgical consult

tbl0009Table 9 Complications of diverticulosis

Fistula

Obstruction

Hemorrhage

Perforation

Peritonitis

Abscess

1540 COLON/Diseases and Disorders

of the intestine that they are prone to infect since the

presenting symptoms vary by region. The initial

evaluation of patients with acute diarrhea should

include a history of the duration of symptoms and

the frequency and characteristics of the stool. The

clinical and epidemiologic history is central to patient

medical evaluation and management. Diarrhea may

be categorized as mild (no change in normal activ-

ities), moderate (forced change in activities), or severe

(disability generally with confinement to bed). There

should be an attempt to elicit the severity of illness,

evidence of dehydration and extracellular volume

contraction (e.g., with orthostatic vital signs), and

character of stool pattern. Fever and peritoneal signs

may be clues to infection with an invasive enteric

pathogen (Shigella, Salmonella,orCampylobacter).

Diagnostic clues may be provided by questioning

about factors that might expose a patient to potential

pathogens such as residence, occupational exposure,

recent and remote travel, pets, and hobbies. A food

history may also provide clues to a diagnosis. Con-

sumption of unpasteurized dairy products, raw or

undercooked meat or fish, or organic vitamin prepar-

ations may suggest certain pathogens. In addition, the

timing of symptoms with regard to exposure to sus-

pected offending food can be important clues to the

diagnosis. Symptoms that begin within 6 h suggest

ingestion of a preformed toxin of Staphylococcus

aureus or Bacillus cereus (Table 11). Symptoms that

begin at 8–14 h suggest infection with Clostridium

perfringens. Symptoms that begin at more than 14 h

suggest infection with viral agents, particularly if

vomiting is the most prominent feature, or bacterial

contamination of food with enterotoxigenic or

enterohemorrhagic E. coli. It is also important to

ask about recent antibiotic use (as a clue to the pres-

ence of Clostridium difficile infection). In the absence

of specific clues in the history, a stool culture should

be obtained in patients with the signs of more severe

illness. Gross examination of the stool for blood, pus,

and mucus is the single most important laboratory

test to begin the evaluation of an acute diarrheal

illness. This should be followed by microscopic exam-

ination of the stool for inflammatory cells. A stool

specimen should be submitted for culture if the stool

is inflammatory (i.e., with white cells and/or mucus).

Specific media, methods, or stains may be required

to isolate or identify organisms of interest. A routine

stool culture will identify Salmonella, Campylobac-

ter, Shigella, Aeromonas, and most strains of Yersinia.

A stool culture that is positive for one of these patho-

gens in a patient with acute diarrheal symptoms can

be interpreted as a true positive, although antibiotic

therapy is not required for all of these organisms.

Other organisms that should be considered in selected

situations include enterohemorrhagic Escherichia

coli, viruses, vibrios, Giardia, Cryptosporidia,and

Cyclospora.

Treatment

0048The management of patients with acute diarrhea

begins with general measures such as hydration and

alteration of diet. Antibiotic therapy is not required in

most cases, since the illness is usually self-limited.

Nevertheless, empiric and specific antibiotic therapy

can be considered in certain situations.

0049For most cases of acute diarrhea, the most import-

ant form of therapy consists of fluid combined with

tbl0010 Table 10 Noninfectious causes of diarrhea

Drugs

Thyroid disease

Carcinoid syndrome

Lactose deficiency

Short gut

Gastrinoma

Tumor

Cystic fibrosis

Schwanoma

IBD

Celiac disease

IBS

tbl0011 Table 11 Infectious causes of diarrhea

Agent Clinical features Syndrome

Staphylococcus aureus, Bacillus cereus

(preformed toxin)

Nausea, vomiting, watery

diarrhea

Gastroenteritis

Enteric pathogen Abdominal pain, cramps,

voluminous stools

Acute watery diarrhea

Shigella, Campylobacter,

Salmonella, Escherichia coli,

Yersinia, Aeromonas spp., noncholera

vibrios, Chlamydia trachomatis

Small volume stools,

urgency, tenesmus, dysentery

Colitis, proctitis

Parasite (Giardia, Cryptosporidium,

Cyclospora, Microsporidium), bacterial overgrowth

Depends upon location

of disease

Persistent, chronic diarrhea

COLON/Diseases and Disorders 1541

electrolytes. Particular attention should be given to

the immunocompromised and the elderly. Solutions

containing sodium in the range of 45–75 mEq l

1

are

required. For dehydrated patients, aggressive fluid

therapy is required. Oral fluids with Na 60–90 mEq

l

1

, K 20 mEq l

1

, Cl 80 mEq l

1

, citrate 30 mEq l

1

,

and glucose 20 g l

1

are often recommended. In non-

dehydrated healthy persons with acute diarrhea, fruit

juices with saltine crackers supplemented with broths

and soups can meet the fluid and salt needs in most

cases. In all cases, calories should be provided to

facilitate enterocyte renewal. Historically, boiled

starches/cereals with salt combined with crackers,

bananas, yogurt, soup and boiled vegetables have

been used successfully. Diet can return to normal

when stools are formed. Starchy foods have the ad-

vantage of containing a small percentage of simple

proteins that are easily hydrolyzed and well absorbed.

Once rehydration is complete and food has been re-

introduced, the oral electrolyte solution is continued

to replace ongoing losses from stool and for mainten-

ance. The rehydration fluid can be safely continued if

other foods or fluids are introduced.

0050 Oral rehydration solutions were first developed in

the USA in the early 1950s following the realization

that, in many small-bowel diarrheal illnesses,

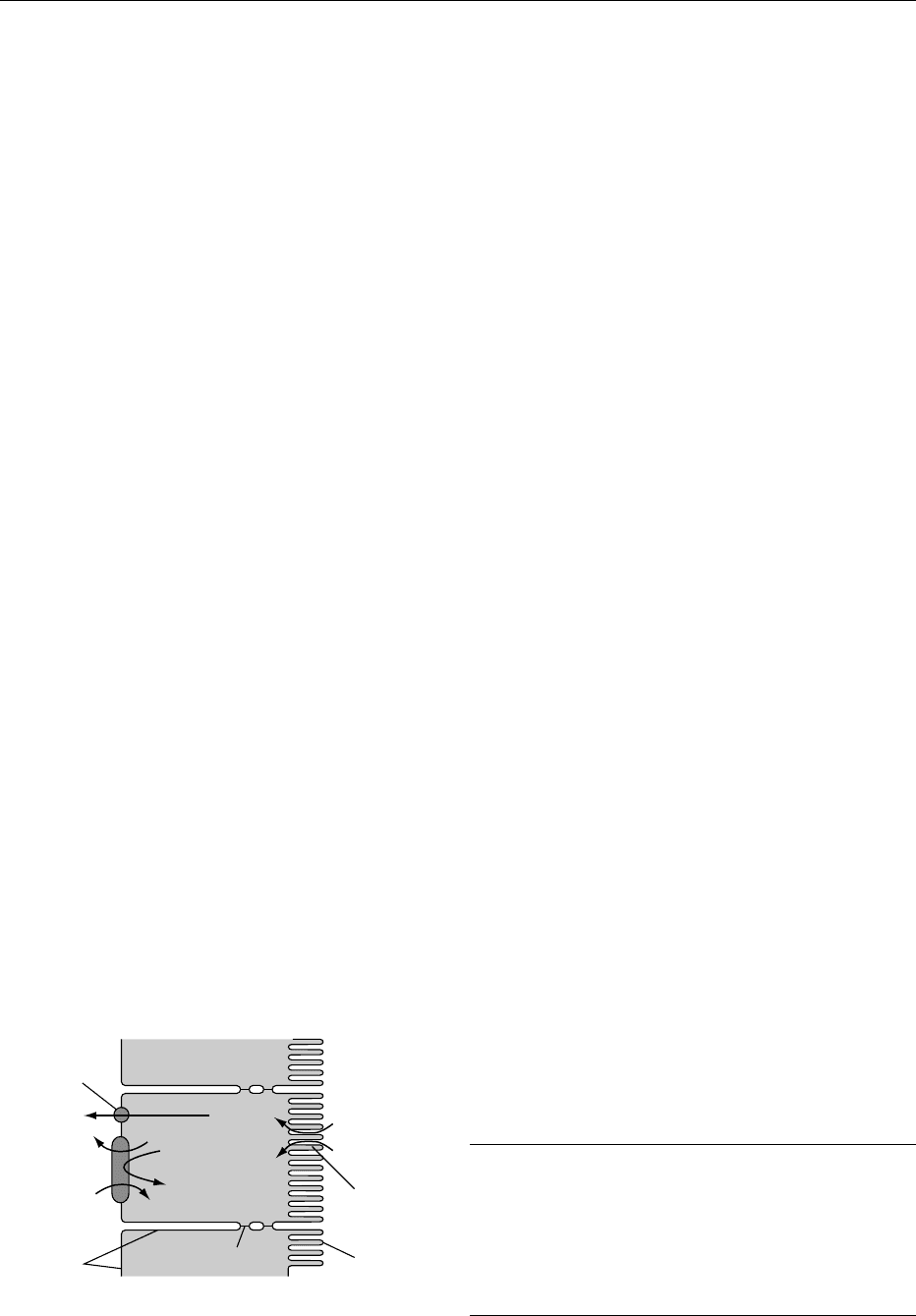

intestinal glucose absorption via sodium–glucose

cotransport remains intact. Thus, in diarrheal disease

caused by any organism that turns on small-bowel

secretory processes, the intestine remains able to

absorb water if glucose and salt are also present to

assist in the transport of water from the intestinal

lumen (Figure 2). From this point of view, it would

seem desirable not to restrict food in acute diarrheal

illnesses. Carefully controlled trials of various regi-

mens and solutions for oral rehydration have been

conducted in nearly every country in the world. The

American Academy of Pediatrics Committee on

Nutrition endorses the use of oral fluid therapy and

posttreatment feeding.

0051A composition of oral rehydration solution (per

liter of water) has been recommended by the World

Health Organization (Table 12).

0052Homemade solutions of sugar and salt can also be

used for oral rehydration. An appropriate mixture is

half a teaspoon of salt (3.5 g) and 8 teaspoons of

sugar (40 g) in 1 liter of water. These homemade

solutions lack sufficient amounts of potassium.

Moreover, potentially harmful errors in mixing have

been reported. The electrolyte concentrations of

fluids used for sweat replacement (e.g., Gatorade)

are not equivalent to oral rehydration solutions,

although they may be sufficient for the otherwise

healthy patient with diarrhea who is not dehydrated.

Diluted fruit juices and flavored soft drinks along

with saltine crackers and broths or soups may also

meet the fluid and salt needs in these less severely ill

individuals. If available, racecadotril, an enkephali-

nase inhibitor, may be an effective adjunct to oral

rehydration solutions. In one study, it reduced the

output and duration of watery diarrhea in a study of

135 Peruvian boys, aged 3–35 months.

0053Several problems with glucose-based oral rehydra-

tion solutions have limited their use. While this ther-

apy effectively replaces the fluids lost in the stool, it

does not decrease the stool volume. The continued

diarrhea often leads to self-imposed cessation of ther-

apy by the user. Glucose-based solutions prepared

with an electrolyte concentration higher than that of

the recommended solutions as a result of the addition

of too much solute can produce an increase in

diarrhea and hypernatremia.

0054In summary, oral rehydration has become the main-

stay for management of acute diarrheal illness caused

by infection. Glucose electrolyte solutions should

be used for rehydration (75–90 mmol of sodium per

liter) and maintenance (40–60 mmol of sodium

per liter). The ratio of carbohydrate to sodium should

not exceed 2:1. Oral rehydration solutions may be

used to treat mild, moderate, and severe dehydration.

Mixing of dry ingredients and water at home is ac-

ceptable if guidelines are strictly followed. Feeding

Intestinal lumen

Dietary glucose

High (dietary) Na

+

Epithelial cells

Low Na

+

High K

+

Blood

High Na

+

Low K

+

Glucose

Glucose

Tight junction

Basolateral

membrane

Glucose

Glut 2

Apical

membrane

Na

+

/glucose

symport

protein

2 Na

+

2 Na

+

ADP + P

i

K

+

K

+

Na

+

ATP

Na

+

Na

+

/K

+

ATPase

fig0002 Figure 2 Sodium–glucose transporter.

tbl0012Table 12 Composition of oral rehydration solution

Ideal 3.5 g of sodium chloride

2.9 g of trisodium citrate or 2.5 g of sodium

bicarbonate

1.5 g of potassium chloride

20 g of glucose or 40 g of sucrose

Homemade 1.5 teaspoons (3.5 g) of salt

8 teaspoons (40 g) of sugar

1 l of water

1542 COLON/Diseases and Disorders

should be reintroduced within the first 24 h of the

onset of diarrhea.

See also: Antioxidants: Natural Antioxidants; Body

Composition; Calcium: Properties and Determination;

Carbohydrates: Classification and Properties; Colon:

Structure and Function; Dietary Fiber: Properties and

Sources; Enteral Nutrition; Fish Oils: Production; Folic

Acid: Properties and Determination; Infection, Fever,

and Nutrition; Inflammatory Bowel Disease; Iron:

Properties and Determination; Malnutrition: The Problem

of Malnutrition; Parenteral Nutrition

Further Reading

Camilleri M (2001) Management of the irritable bowel

syndrome. Gastroenterology 120: 652–668.

Drossman DA (2000) The Functional Gastrointestinal

Disorders. McLean, UA, USA: Allen Press.

DuPont HL (1997) Guidelines on acute infectious diarrhea

in adults. The Practice Parameters Committee of the

American College of Gastroenterology 92(11): 1962.

Feldman M, Sleisenger MH and Fordtran JS (eds) (1998)

Gastrointestinal and Liver Diseases, 6th edn. Phila-

delphia, PA: W.B. Saunders.

Greenberg GR (1992) Nutritional support in inflammatory

bowel disease: Current status and future directions.

Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology 27(supple-

ment 192): 117–122.

Guerrant RL, Gilder TV and Steiner T (2001) IDSA Practice

guidelines for the management of infectious diarrhea.

Clinical Infectious Diseases 32: 331.

Hawkins C (1990) Ulcerative colitis: dietary therapy. In:

Inflammatory Bowel Diseases. Edinburgh, UK: Church-

ill-Livingstone.

Jeejeebhoy KN (2002) Clinical nutrition. Management of

nutritional problems of patients with Crohn’s disease.

Canadian Medical Association Journal 166(7): 913–

918.

Kohler L, Sauerland S and Neugebauer E (1999) Diagnosis

and treatment of diverticular disease: Results of a con-

sensus development conference. The Scientific Commit-

tee of the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery.

Surgical Endoscopy 13: 430.

Parks TG (1975) Natural history of diverticular disease of

the colon. Clinical Gastroenterology 4: 53.

Practice Parameters for the Treatment of Sigmoid Diverticu-

litis. The Standards Task Force. The American Society of

Colon and Rectal Surgeons. Diseases of the Colon and

Rectum 43: 289.

Ramaswamy K (2001) Infectious diarrhea in children.

Gastroenterology Clinics of North America 30(3):

611–624.

Rosenberg IH (1990) Diet and nutritional therapy in

Crohn’s disease. In: Inflammatory Bowel Diseases.

Edinburgh, UK: Churchill-Livingstone.

Stollman NH and Reskin JB (1999) Diagnosis and manage-

ment of diverticular disease of the colon in adults. Ad

Hoc Practice Parameters Committee of the American

College of Gastroenterology. American Journal of

Gastroenterology 94: 3110.

Cancer of the Colon

S-W Choi and J B Mason, Tufts University, Boston,

MA, USA

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Background

0001Colorectal cancer is the second most common cancer

in terms of incidence and mortality for both men and

women in most of the developed countries of the

world. Molecular-genetic studies indicate that colon

carcinogenesis is due to a time-dependent accumula-

tion of aberrations in tumor suppressor genes and

oncogenes in the colonic epithelial cell, leading to

abnormal expression of critical, cancer-related pro-

teins. These aberrations, the most well characterized

of which are mutations, offer a molecular explan-

ation for the generally accepted sequence of colon

carcinogenesis: normal mucosa, hyperproliferative

epithelium, adenoma, and carcinoma.

0002The majority of colorectal cancers (65–85%) are

described as ‘sporadic’ and have no apparent under-

lying genetic predisposition, whereas it is estimated

that at least 5% of colorectal cancers are due to

inherited mutations in major genes (‘hereditary’

colon cancer), and up to an additional 30% may

be due to minor susceptibility genes (‘familial’ colo-

rectal cancer). Hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal

cancer and familial adenomatous polyposis are the

two major varieties of hereditary colorectal cancer

syndromes.

0003Migrant studies and other epidemiologic studies

indicate that the incidence of sporadic colon cancer is

strongly associated with environmental determinants,

in particular diet. A diet rich in foods from

plant sources (vegetables, fruits, and whole grains)

is associated with decreased risk, whereas diets high

in animal fat and red meats are associated with in-

creased risk for colorectal cancer. Making appropri-

ate changes in dietary habits and/or supplementing

the diet with particular nutrients that are thought

to be protective is therefore an attractive approach

to preventing this cancer, although it should be

emphasized that the prevention of colorectal cancer

by this means probably requires long-term changes

COLON/Cancer of the Colon 1543

over a decade or more in order to effect a meaningful

response.

Epidemiology

0004 Rates of colorectal cancer vary considerably with

geography. The disease is common in the USA,

Australia, New Zealand, Scandinavia, and Western

Europe, and is relatively uncommon in Asia, Africa,

and South America. Incidence rates vary approxi-

mately 20-fold around the world, with the highest

rates seen in the developed world and the lowest in

India. The international differences, migration data,

and recent rapid changes in incidence rates in Italy,

Japan, urban China, and male Polynesians in Hawaii

show that colon cancer is highly sensitive to changes

in the environment. Among immigrants and their

descendants, incidence rates rapidly reach those of

the host country, sometimes within the migrating

generation. The 20-fold international difference may

be explained, in large part, by dietary and other en-

vironmental differences; indeed, although incidence

rates in Japan have been low even until quite recently,

the highest rates in the world are now seen among

Hawaiian Japanese.

0005 However, colorectal cancer has long been known

to occur more frequently in certain families, and there

are several rare genetic syndromes that convey a

markedly elevated risk. For example, familial adeno-

matous polyposis, an autosomal dominant hereditary

disease, has 90–100% penetrance, with essentially all

affected individuals developing colon adenomas, and

later colon cancer. Colorectal cancer arising in this

setting is thought to have nearly a 100% genetic

basis. Colorectal cancer is thus causally related to

both genes and environment.

Fat

0006 In Western diets, much of the fat is derived from

animal products and may constitute 40–45% of

total caloric intake. The relationship between dietary

fats and cancer has long been recognized and has

received considerable attention as a possible risk

factor in the causation of colon cancer. A recent eco-

logical study observed that mortality data of color-

ectal cancer for 22 European countries, the USA, and

Canada were correlated with consumption of animal

fat. Increased concentrations of bile acids and fatty

acids in the intestine, resulting from a high-fat diet, is

suggested as an explanation for the epidemiological

association between high intake and high rates of

colorectal cancer. Bile acids and fatty acids are con-

sidered to be major irritants of the colonic mucosa

and are thought to link the high-risk Western-style

diet to colon cancer. However, the link between

animal fat and colorectal cancer is not entirely con-

sistent. The majority of case-control studies of diet

and cancer have shown no significant associations.

Furthermore, prospective and intervention studies of

fat in studies of the precursor adenoma have yielded

conflicting results. The risk of developing an aden-

oma was reduced by a low-fat diet in a prospective

study of 45 000 US health professionals, but not in

an intervention study of 400 adenoma patients in

Australia.

0007Not all dietary fats are detrimental in this regard.

Intake of vegetable fat is usually shown not to be

associated with risk of the cancer. Also, European

epidemiologic studies indicate an inverse relationship

between fish consumption and colorectal cancer and

an inverse correlation with fish and fish oil consump-

tion when expressed as a proportion of total or

animal fat. These effects were seen in populations

with a high fat intake, indicating that the type of fat

in the diet is critical in determining cancer risk. Con-

sumption of fish products rich in o-3 polyunsaturated

fatty acids (PUFA), such as eicosapentaenoic and

docosahexaenoic acid, is associated with a low inci-

dence of colorectal cancer and adenoma. Moreover,

PUFAs have been shown to normalize altered prolif-

erative patterns of the colonic mucosa in human sub-

jects at high risk for colon cancer. These results

emphasize that the enhancing effect of colon carcino-

genesis by dietary fat depends on the type of fat as

well as the fatty acid composition of the fat.

Meat

0008Most case-control studies show an increased risk for

development of colorectal cancer in those individuals

consuming high amounts of meat, especially red meat

(this includes lamb, pork, and beef). A high intake of

processed meat is also associated with colorectal

cancer risk in two cohort studies. Possible mechan-

isms underlying this epidemiological association

include the heterocyclic amines (which are carcino-

genic and mutagenic) that are formed when meat is

cooked. The possibility that meat alters nitrogen

metabolism within the lumen of the intestine and

enhances the production of endogenous promoters

and carcinogens within the colon is also an attractive

mechanism. In a review of several large prospective

cohort studies, colon cancer risk was associated with

red-meat consumption but not with total or animal

fat, which suggests that the risk associated with red-

meat consumption is independent of its fat content.

0009In contrast, consumption of fish or chicken is not

associated with risk and might even reduce the occur-

rence of colorectal cancer. A cohort study in Iowa

1544 COLON/Cancer of the Colon

women and European prospective studies did not

found any significant association between overall

meat intake and colon cancer, and two prospective

studies show that consumption of white meat or fish

is not associated with risk and might even reduce the

occurrence of colorectal cancer. A study of Seventh-

day Adventists – a predominantly vegetarian popula-

tion – reported that meat intake was not associated

with risk of colorectal cancer.

0010 The data suggest an independent association

between red-meat consumption and the risk of color-

ectal cancer; neither the total protein nor the total fat

content of the meat seems to be responsible for this

affect.

Calories

0011 Case-control studies suggest that excess calories

enhance the risk of colonic carcinogenesis, although

it is very difficult to distinguish between energy intake

and the intake of dietary fat. In an animal study,

carcinogen-induced colon tumors were inhibited by

calorie restriction, even though the calorie-restricted

rats ingested twice as much fat as control rats. In

other animal studies, the incidence and multiplicity

of colon tumors were significantly inhibited in

animals fed diets containing 20–30% fewer calories

than controls.

0012 Obesity appears to be a risk factor for colorectal

cancer independent of dietary fat intake. Positive cal-

orie balance and the resulting accumulation of body

fat during adult life increase the risk of colon cancer.

Even a moderate degree of overweight (body mass

index (kg m

2

) > 26) is associated with increased

rates of colorectal cancer. Therefore, maintaining

weight in a desirable range appears to be protective.

Vegetables and Fruits

0013 Among the most consistent data that are available

from the observational epidemiologic literature are

those suggesting that a higher intake of plant foods

lowers the risk of cancers at almost every site. The

overwhelming majority of descriptive, case-control,

and cohort epidemiologic studies have suggested

an inverse relationship between consumption of

vegetables and fruits and colorectal cancer risk.

0014 There are many biologically plausible reasons why

consumption of vegetables and fruits might reduce

the likelihood of cancer. Numerous compounds in

vegetables and fruits that might exert anticarcino-

genic effects have been identified, such as carote-

noids, vitamin C and E, folate, flavonoids, phenols,

isothiocyanates, and fiber. Each of these phytochem-

icals and bioactive compounds has been shown to

exert some anticarcinogenic activity in laboratory

models of cancer.

0015Vegetables are observed more consistently to

convey a protective effect against colorectal cancer

than fruit in studies from many countries. This may

be due to a difference in composition between vege-

tables and fruits. An average serving of fruit is sub-

stantially higher in sugar, calories, and vitamin C, but

lower in carotenoids, vitamin B

6

, and folate relative

to vegetables. Conversely, raw vegetables tend to be

lower in fiber (especially the soluble variety) than

both cooked vegetables and fruits. Alternatively, a

high vegetable intake, more than a high fruit intake,

may merely reflect a generally healthier diet, that is,

one relatively low in energy, fat, and sugar.

0016Although the vast majority of case-control and

cohort studies have observed a protective effect of

vegetables and fruits on colorectal carcinogenesis,

the Iowa Women’s Health Study, a large prospective

cohort study, observed that total intake of neither

vegetables nor fruits reduced the relative risk of color-

ectal cancer. Similar results were obtained when each

vegetable or fruit item was independently analyzed,

except garlic. The data from the meta-analyses

of colorectal and stomach cancer suggest that a

high intake of raw and cooked garlic may be associ-

ated with a protective effect against stomach and

colorectal cancers. Garlic contains glutathione-S-

transferase, which is thought to be involved in

the detoxification of several potential carcinogens.

Individuals consuming more than one garlic clove

per week had a 32% reduction in the risk of colo-

rectal cancer compared to those not eating any garlic.

Fiber

0017The fiber hypothesis is an old hypothesis that origin-

ated from an epidemiologic study in which African

blacks consuming high-fiber, low-fat diets were ob-

served to have a lower mortality from colorectal

cancer than African whites consuming a low-fiber,

high-fat diet. The majority of subsequent observa-

tional epidemiologic and case-control studies support

a protective effect of fiber-rich diets. The effect is

thought to be mediated by the shorter intestinal tran-

sit time that accompanies a high-fiber diet and the

resultant decrease in duration of exposure of the co-

lonic mucosa to potential carcinogens, as well as an

increase in stool bulk, which would dilute the colonic

contents, including any potential carcinogens.

0018Fiber is found in vegetables, fruits, whole grains,

seeds, nuts, and legumes and consists of nonpoly-

saccharides (such as lignin) and nonstarch polysac-

charides (including cellulose, hemicellulose, pectin,

gums, and mucilages). Earlier data suggested that a

COLON/Cancer of the Colon 1545