Caballero B. (ed.) Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition. Ten-Volume Set

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

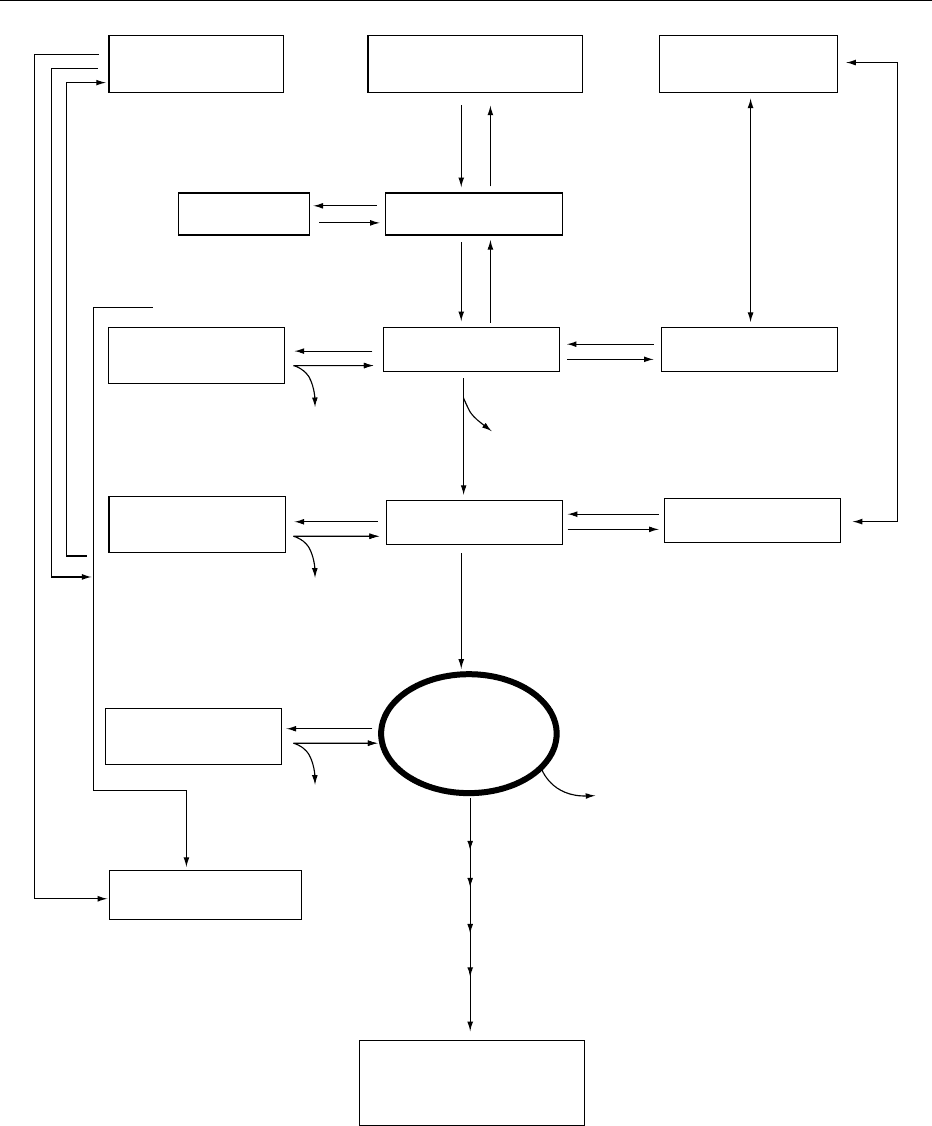

metabolism is illustrated in Figure 1. Cofactors are

essential in numerous biochemical pathways, includ-

ing the breakdown, or catabolism, of nutrients and

the synthesis, or anabolism, of biological compounds.

The vitamin and mineral cofactors complex with

enzymes to convert nutrients into usable energy and

produce biomolecules that are the basis of life. (See

Minerals – Dietary Importance; Trace Elements; Vita-

mins: Overview.)

Nutrients as Coenzymes and Cofactors

0003 Without the required vitamins and minerals, cofac-

tor-dependent enzymes could not mediate metabol-

ism or maintain normal cell function and biological

processes that are essential for cell division, differen-

tiation, growth, and repair. Nutrient cofactors are

also necessary for the structural integrity of certain

hormones and regulatory proteins.

Vitamins

0004 All of the water-soluble vitamins and two of the fat-

soluble vitamins, A and K, function as cofactors or

coenzymes. Coenzymes participate in numerous bio-

chemical reactions involving energy release or catab-

olism, as well as the accompanying anabolic reactions

(Figure 1). In addition, vitamin cofactors are critical

for processes involved in proper vision, blood coagu-

lation, hormone production, and the integrity of

collagen, a protein found in bones. (See Retinol:

Physiology.)

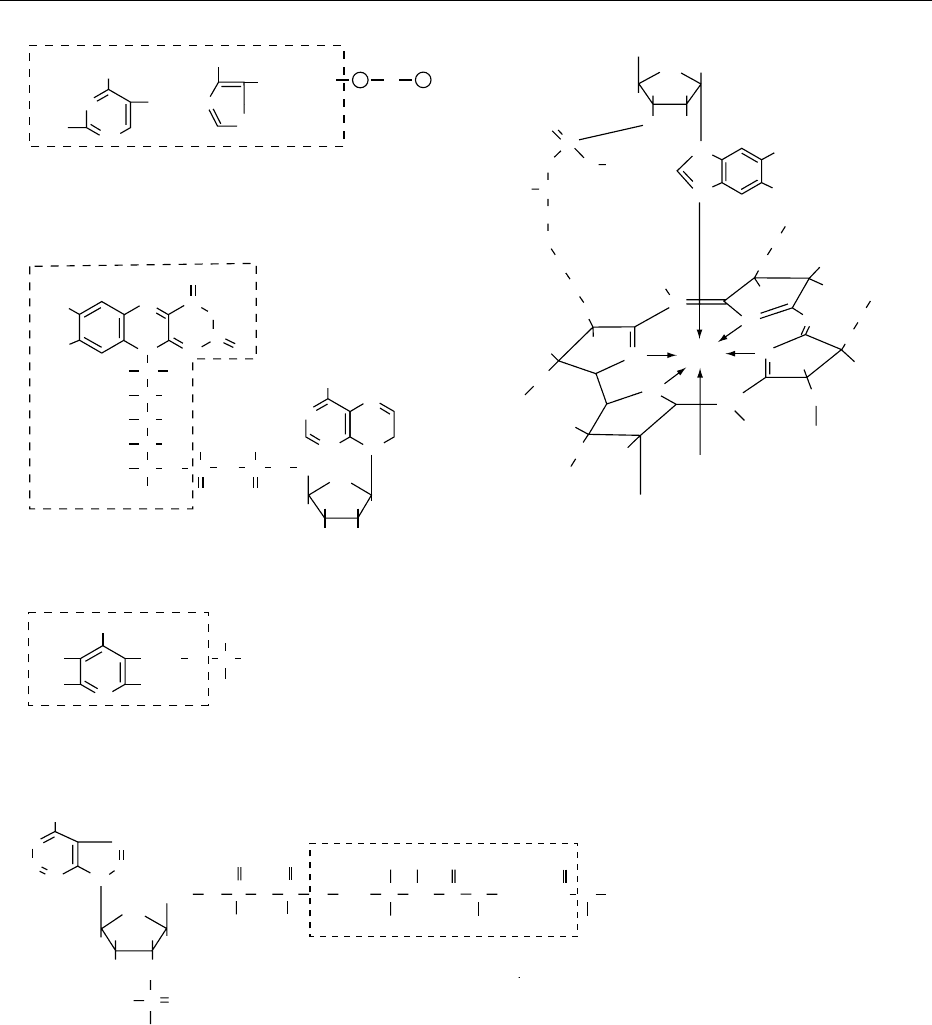

0005 The active coenzyme form of thiamin, vitamin B

1

,is

thiamin pyrophosphate (TPP) (Figure 2a). TPP is in-

volved in oxidative decarboxylation and transketolase

reactions. An example is the decarboxylation (re-

moval of —COO

--

) of three-carbon pyruvate to two-

carbon acetyl coenzyme A (CoA), an important step in

carbohydrate breakdown. (See Thiamin: Physiology.)

0006 The active forms of riboflavin, vitamin B

2

, are the

coenzymes flavin mononucleotide (FMN; Figure 2b)

and flavin adenine dinucleotide (FAD). These

coenzymes serve as hydrogen carriers for oxidation

reactions that affect energy nutrients in the citric

acid cycle and in the electron transport system. (See

Riboflavin: Physiology.)

0007 The coenzyme forms of nicotinic acid are nicotina-

mide adenine dinucleotide (NAD) and nicotinamide

adenine dinucleotide phosphate (NADP). These com-

pounds assist dehydrogenase enzymes in the catabol-

ism of fat, carbohydrates, and amino acids, and in the

enzymes involved in synthesis of fats and steroids

and other vital metabolites. (See Niacin: Physiology.)

0008 Pyridoxal phosphate (PLP; Figure 2c) and pyridox-

amine phosphate (PMP) are the coenzyme forms of

vitamin B

6

. These are cofactors for approximately

120 enzymes, such as the transaminases, racemases,

decarboxylases, cleavage enzymes, synthetases,

dehydratases, and desulfydrases. Both PLP and PMP

participate in the metabolism of amino acids, includ-

ing transamination, racemization, deamination, and

desulfhydration, and the conversion of tryptophan to

nicotinic acid. (See Vitamin B

6

: Physiology.)

0009Pantothenic acid (PA) is a B vitamin that is a

component of coenzyme A (Figure 2d). Coenzyme A

is necessary for the metabolism of carbohydrates,

amino acids, fatty acids, and other biomolecules. As

a cofactor of the acyl carrier protein, pantothenic acid

participates in the synthesis of fatty acids. (See Osteo-

porosis.)

0010The coenzyme forms of vitamin B

12

are methyl-

cobalamin (Figure 2e) and deoxyadenosylcobalamin.

These assist in the conversion of homocysteine to

the amino acid methionine, the oxidation of amino

acids and odd-chain fatty acids, and the removal

of a methyl group from methyl folate, which regener-

ates tetrahydrofolate. (See Cobalamins: Physiology.)

0011Biotin as the coenzyme biocytin functions in

carboxylation reactions that convert odd-carbon-

numbered amino acids and fatty acids to even-

carbon-numbered compounds, which can then be

metabolized. Biocytin is also necessary for the synthe-

sis of pyrimidines and the formation of urea. Some

holoenzymes containing biotin act as carboxylases to

convert acetyl CoA to cholesterol precursors, and

as transcarboxylases and decarboxylases in other

important reactions. (See Biotin: Physiology.)

0012A coenzyme of folate is tetrahydrofolate (THF),

a carrier of one-carbon units, such as methyl groups

(—CH

3

). One-carbon units arise primarily from the

metabolism of amino acids. They are needed to inter-

convert amino acids and to synthesize purines and

pyrimidines for the formation of RNA and DNA.

(See Nucleic Acids: Physiology.)

0013Vitamin C (ascorbic acid) is a cofactor for the

hydroxylases. Some examples are the hydroxylation

of proline and lysine to create cross-links from intra-

molecular hydrogen bonds that are critical to the

structural integrity of collagen, the hydroxylation of

cholesterol to form bile acids, and the hydroxylation

of tyrosine to form the hormone norepinephrine (nor-

adrenaline). (See Ascorbic Acid: Physiology.)

0014The aldehyde form of vitamin A, retinal, is a cofac-

tor for apoproteins in the eye called opsins. Opsins

are responsible for dim-light vision in the rods (rhod-

opsin) and are involved in color and bright-light

vision in the cone of the retina (iodopsin). When

light strikes the retinal bound to opsin, the conform-

ation of the retinal is changed (photoisomerization)

such that photoreceptor cell membranes are

1476 COENZYMES

Proteins

Glycogen

Carbohydrates

Glucose

Pyruvate

Glucogenic

amino acids

Magnesium

Copper

Magnesium

Manganese

NAD

(nicotinic acid)

TPP (B

1

)

Acetyl CoA

CoA

(pantothenic

acid)

NAD

(nicotinic

acid)

Ketogenic

amino acids

Chromium, zinc

Magnesium,

calcium

Fat

(lipids)

Glycerol

NAD (nicotinic acid)

Magnesium

Magnesium,

sulfur

Fatty acids

Biotin

Magnesium

Manganese

NAD (nicotinic acid)

CoA (pantothenic acid)

NAD (nicotinic acid)

Magnesium

Glucogenic

amino acids

THF

(folic acid)

B

12

(cobalt)

Nonprotein derivatives

(RNA, DNA)

CITRIC

ACID

CYCLE

CO

2

CO

2

NH

3

CO

2

B

6

B

6

NH

3

B

6

NH

3

B

6

Copper

Iron

FMN, FAD (B

2

)

Magnesium

Manganese

NAD (nicotinic acid)

Zinc

ENERGY

(ATP and heat)

CO

2

H

2

O)

Electron transport

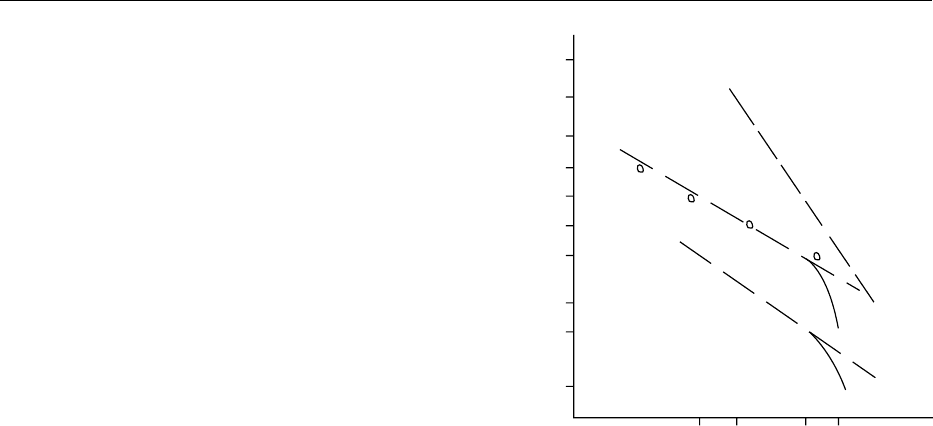

fig0001 Figure 1 Overview of carbohydrate, protein, and lipid (fat) metabolism. Vitamins and minerals play crucial roles as coenzymes and

cofactors in both the energy-releasing, catabolic pathways and the anabolic pathways involved in the synthesis of proteins, lipids,

carbohydrates, and nucleic acids. NAD, nicotinamide adenine dinucleotide; TPP, thiamin pyrophosphate; CoA, coenzyme A; THF,

tetrahydrofolate; FMN, flavin mononucleotide; FAD, flavin adenine dinucleotide; ATP, adenosine triphosphate. Reproduced from

Coenzymes, Encyclopaedia of Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK, and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic

Press.

COENZYMES 1477

hyperpolarized and the optic nerve transmits signals

to the brain interpreted as vision. Retinoic acid is the

metabolite form of vitamin A that regulates genes. It

binds to proteins called retinoic acid receptors

(RARs) and retinoid X receptors (RXRs). These pro-

teins are transcription factors belonging to the ster-

oid/thyroid hormone receptor superfamily of proteins

and are found throughout the body. The RAR/RXR

proteins bind to and regulate the transcription of

numerous target genes important for cell develop-

ment.

0015Vitamin K acts as a coenzyme for g-carboxylases,

enzymes that transfer —CO

2

groups. The resulting

carboxylic acid groups are available for calcium

NH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

O

CH

2

CH

2

CONH

2

CH

2

OH

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

3

CH

2

CH

CH

CO

2

NH

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

CH

CH

NH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CONH

2

CONH

2

CONH

2

CONH

2

N

N

S

N

NC

C

N

C

N

H

3

C

3

HC

3

HC

3

HC

H

3

C

H

3

C

NH

2

N

N

N

N

H

3

C

H

3

C

P

P

O

(a)

Thiamin

−

+

NH

O

O

HH

CHOH

CHOH

CHOH

OH

CH

H

O

PO

O

OH

PO

O

HH

H

H

O

OH

POH

OH

O

OH OH

HO

N

H

CHO

(b) Riboflavin

(c) Pyridoxal

O

O

O

CH

CO

O

O

P

HO

H

N

N

C

N

N

N

H

H

H

H

P

P

O

O

OO

O

O

OH

OH

OH

HO

N

N

N

N

N

H

H

H

H

H

H

H

NH

Co

+

(e)

P

OCC

H

O

O

OH

NCH

2

CH

2

C

O

OH

H

NCH

2

CH

2

SH

(d)

Pantothenic acid

fig0002 Figure 2 Selected examples of vitamins as coenzymes: (a) thiamin pyrophosphate; (b) flavin mononucleotide; (c) pyridoxal

phosphate; (d) coenzyme A; and (e) methylcobalamin or coenzyme B

12

. Reproduced from Coenzymes, Encyclopaedia of Food Science,

Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson RK, and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

1478 COENZYMES

binding. Gamma-carboxylation is necessary for the

formation of osteocalcin, a protein important in bone

remodeling, and prothrombin, a coagulation factor

(II) involved in blood clotting (See Vitamin K:

Physiology).

Minerals

0016 Minerals participate as both catalysts and cofactors

in biological reactions. As catalysts, minerals are not

part of an enzyme or substrate, but accelerate the

reaction between the two. As cofactors, they become

a structural component that is essential for the func-

tion of an enzyme or protein. Minerals that play

critical roles as cofactors for enzymes include magne-

sium, manganese, molybdenum, and selenium. Other

minerals, such as calcium, cobalt, phosphorus, and

iodine, act as essential cofactors for nonenzymatic

proteins. Zinc, copper, and iron are cofactors for

both enzymatic and nonenzymatic proteins.

Mineral Cofactors in Enzymatic Reactions

0017 Some examples of how minerals serve as cofactors for

enzymes involved in metabolism are as follows.

0018 Magnesium (Mg) is required as a cofactor for

over 300 enzyme reactions. One critical function is

the stabilization of the structure of adenosine tri-

phosphate (ATP). Energy provided by magnesium-

dependent ATP hydrolysis is required during the

catabolism of carbohydrates (glycolysis and the citric

acid cycle) and fatty acids (b-oxidation) and the an-

abolism of proteins. Magnesium also plays a cofactor

role in enzymes involved in the synthesis of DNA, and

it helps maintain the double helical structure of DNA.

(See Magnesium.)

0019 Manganese (Mn) has been identified as an essential

cofactor in several metalloenzymes. Some examples

are: (1) superoxide dismutase, a mitochondrial

enzyme which catalyzes the breakdown of superoxide

free radicals to hydrogen peroxide and water, thereby

protecting cells from free radical damage; (2) argi-

nase, which helps in the production of nitric oxide

and the urea cycle; and (3) phosphoenol-pyruvate

carboxykinase, which participates in carbohydrate

metabolism. Manganese is also important (but not

essential) in activating the glycosyltransferases,

which are necessary for the formation of glyco-

proteins and proline depeptidase, which catalyzes

the final step in the breakdown of collagen.

0020 Molybdenum (Mb) is a cofactor for several oxida-

tion enzymes. Xanthine oxidase is necessary for the

production of uric acid from purines; sulfite oxidase

converts sulfite to sulfate; and aldehyde oxidase is

involved in the hydroxylation of heterocyclic nitrogen

compounds, such as nicotinic acid.

0021Selenium (Se) functions as a component of enzymes

involved as antioxidants (glutathione peroxidase) and

in thyroid hormone metabolism (5

0

-deiodinases). Al-

though the metal is needed for activity, it is not a

cofactor since it is incorporated in protein as the

amino acid selenocysteine. (See Selenium: Physiology.)

0022Zinc (Zn) is an essential component for more than

100 enzymes. Examples of zinc-containing enzymes

are found in all known classes of enzymes, including

transferases, hydrolases, oxidoreductases, lyases, iso-

merases, and ligases. Zinc is a cofactor in key bio-

chemical reactions in the body, such as carbohydrate,

lipid, and protein metabolism, stabilization of mem-

branes, and synthesis and catabolism of DNA and

RNA. Consequently, zinc is an important contributor

to the processes of replication (synthesis of new

DNA), transcription (synthesis of messenger RNA),

and translation (synthesis of enzymatic and nonenzy-

matic proteins). Some of the general biological func-

tions depending upon the cofactor functions of zinc

include cell replication, tissue growth and repair,

bone formation, skin integrity, and cell-mediated

immunity. (See Zinc: Physiology.)

Mineral Cofactors in Nonenzymatic Molecules

0023Minerals also serve as integral structural components

of a variety of nonenzymatic proteins, as well as for

hormones and vitamin B

12

.

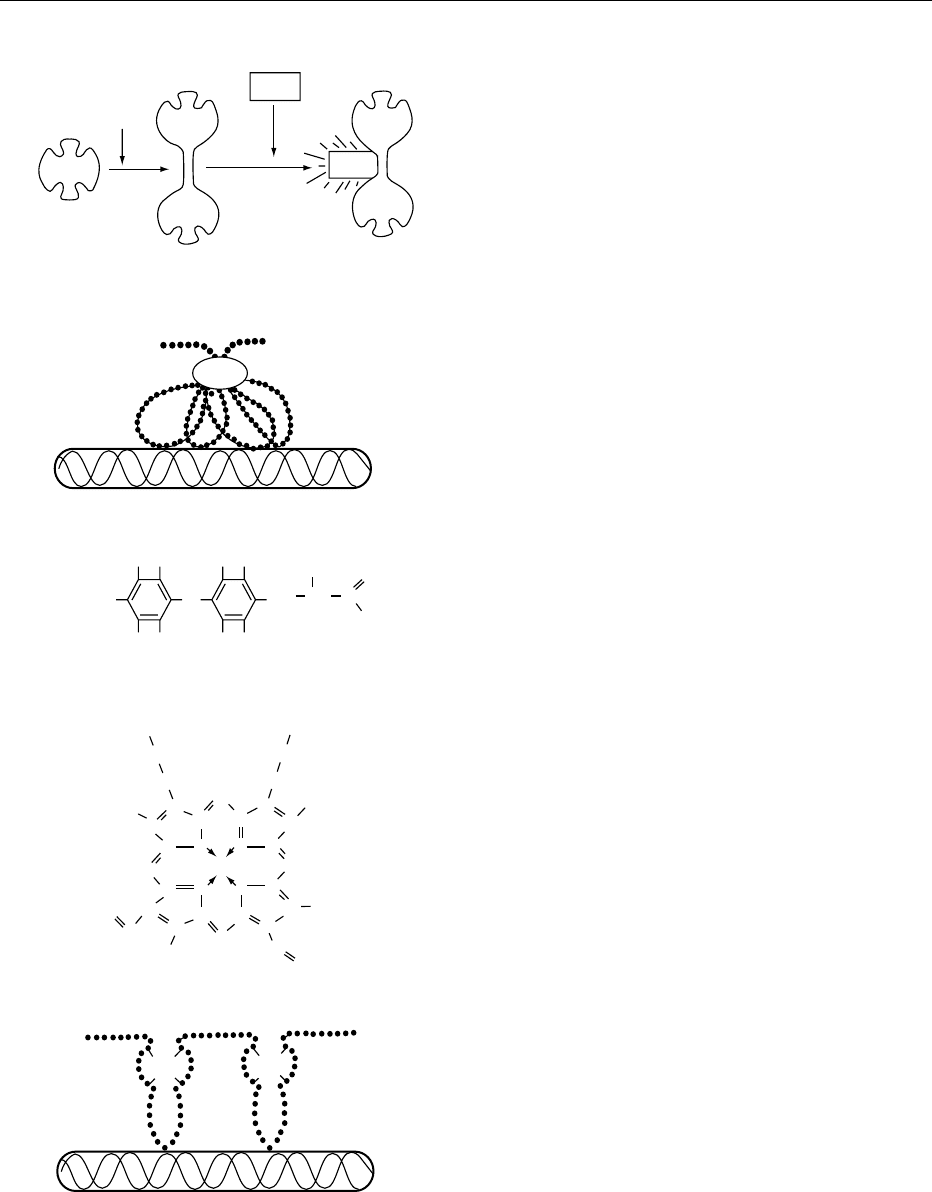

0024Calcium (Ca) functions as a cofactor when it forms

a complex with two structurally related proteins –

calmodulin and troponin C. Calmodulin is a protein

with two globular lobes, each having two binding

sites for calcium (Figure 3a). When calcium ions

bind to calmodulin, a variety of calcium-dependent

enzymes are activated, including membrane phos-

phorylase kinases and some forms of cyclic nucleotide

phosphodiesterases and adenylate cyclases. These

enzymes change the three-dimensional conformation

of the target protein and influence the activity of

signaling pathways whereby cell surface receptors

transmit extracellular signals into cellular responses.

For example, the hormones epinephrine (adrenaline)

and glucagon react with their respective cell surface

receptors to signal the cell to utilize glycogen (the

storage form of glucose). These ‘signals’ induce phos-

phorylation of the enzymes involved in the synthesis

(glycogen synthase) and degradation (glycogen phos-

phorylase) of glycogen.

0025Troponin C is a muscle protein that is structurally

similar to calmodulin. When this protein is activated

by calcium binding, it enhances interactions between

actin and myosin, proteins involved in muscle con-

traction. (See Calcium: Physiology.)

0026Cobalt (Co) is a central atom in the structure of

vitamin B

12

(Figure 2e). This vitamin is essential for

COENZYMES 1479

carbon transfer reactions involved in the synthesis of

DNA and regeneration of methionine. (See Cobalt.)

0027Copper (Cu) ions play a critical role in the structure

of some transcription-regulating proteins. In the pres-

ence of copper ions, certain transcription factors ac-

quire a loop-like structure which forms a cluster close

around the copper ions (Figure 3b). This complex is

called a ‘copper fist’ since it appears to be similar to a

fist clutching a small object. The loop ‘knuckles’ of the

fist are thought to bind to a regulatory region (pro-

moter) of themetallothionein gene. Once the transcrip-

tion factor–copper complex (copper fist) is bound to

the promoter region, another part of the transcription

factor stimulates gene transcription. The translated

metallothionein protein regulates copper levels and

prevents toxicity. (See Copper: Physiology.)

0028Iodine (I) forms part of the thyroid hormones,

thyroxine (Figure 3c), and thyronine. Both hormones

help regulate the basal metabolic rate of organisms.

(See Iodine: Physiology.)

0029Iron (Fe) is a critical constituent of heme (Figure

3d) which forms part of the hemoglobin and myo-

globin molecules. Hemoglobin transports oxygen

to and carbon dioxide away from cells in the body;

myoglobin stores oxygen in muscles. (See Iron:

Physiology.)

0030Phosphorus (P) forms part of the energy-storage

compound ATP. The removal of phosphate (de-

phosphorylation) from ATP to form adenosine diphos-

phate (ADP) releases considerable biochemical energy.

Adding the phosphate (phosphorylation) to ADP to

form ATP again permits the body to store energy. The

storage and release of energy via interconversions of

ATP and ADP is one way the major components of

food (carbohydrates, fats, and protein) ultimately pro-

vide energy for the body. Other types of reversible

phosphorylation help regulate the conformation and

activity of certain proteins such as enzymes.

0031Zinc ions are also needed for the structure of some

transcription factors. The transcription of certain

genes is regulated by DNA-binding proteins that con-

tain important functional domains characterized as

‘zinc fingers’ (Figure 3e). Zinc stabilizes the folding of

the transcription factor into a ‘finger loop’ which is

capable of site-specific binding to double-stranded

DNA. Zinc finger loops are present in the DNA-

binding domains of receptors for glucocorticoids,

mineralocorticoids, estrogen, progesterone, thyroid,

1,25-dihyroxy-vitamin D

3

, and retinoic acid.

Effect of Nutrient Deficiencies

0032A primary deficiency of an essential vitamin or mineral

cofactor is caused by inadequate amounts of the nutri-

ent in the diet. A secondary deficiency occurs because

CN

Calmodulin

(a)

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Cu

2+

Fe

2+

Zn

2+

Zn

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Ca

2+

Inactive

enzyme

Active

enzyme

DNA

(b)

IH

IH IH

IH

HO

O

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

2

CH

3

CH

2

CH

3

CH

3

CH

CH

2

NH

2

CH

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

C

N

NN

N

HC

O

OH

(c)

DNA

N

C

COO

−

COO

−

H

H

3

C

H

2

C

H

C

H

C

H

(d)

(e)

fig0003 Figure 3 Selected examples of minerals as cofactors: (a) calmo-

dulin; (b) copper-fist motif; (c) thyroxine or T

4

; (d) heme; and (e)

zinc-finger motif. Reproduced from Coenzymes, Encyclopaedia of

Food Science, Food Technology and Nutrition, Macrae R, Robinson

RK and Sadler MJ (eds), 1993, Academic Press.

1480 COENZYMES

of something other than diet, such as a disease state or

metabolic alteration, which leads to decreased absorp-

tion, impaired transportation, or increased require-

ments, utilization, or excretion. If a deficiency of a

nutrient continues, body stores begin to diminish.

0033 A continued insufficiency of a nutrient cofactor

will impair or inhibit biochemical functions of the

dependent enzyme. The lack of a functional enzyme–

cofactor complex produces an accumulation of the

substrate and a deficit of the enzyme product. At

this point, measurements of biochemical parameters

may indicate a problem that is not yet evident by a

physical examination. This condition is known as a

subclinical deficiency state. Eventually the deficiency

state is developed to the point at which it can be

observed physically and produces the classical clinical

symptoms of a nutrient deficiency.

0034 An example of this process is seen when a dietary

deficiency of iron produces iron-deficiency anemia.

Inadequate dietary intake of the minerals leads to

declining stores in the body. A sensitive clinical test

that measures the amount of the body’s iron-carrying

protein, transferrin, and the amount of iron it is

carrying can detect a developing iron deficiency

before many of the symptoms of anemia are observed.

As body stores continue to be depleted, a lack of

sufficient iron impairs the production of heme, a

prosthetic group necessary for the formation of

hemoglobin in red blood cells. The production of

red blood cells declines and the reduced cell number

can be determined by a simple clinical blood test

called a hematocrit. When the decreased number of

red blood cells cannot transport enough oxygen to

the peripheral tissues, the result is fatigue, a clinical

symptom associated with iron-deficiency anemia.

(See Anemia (Anaemia): Iron-deficiency Anemia.)

See also: Anemia (Anaemia): Iron-deficiency Anemia;

Ascorbic Acid: Physiology; Calcium: Physiology;

Cobalamins: Physiology; Enzymes: Functions and

Characteristics; Iron: Physiology; Magnesium; Minerals

– Dietary Importance; Niacin: Physiology; Selenium:

Physiology; Thiamin: Physiology; Trace Elements;

Vitamin K: Physiology; Vitamins: Overview; Zinc:

Physiology

Further Reading

Berdanier CD (1998) Advanced Nutrition Micronutrients.

Boca Raton, Florida: CRC Press.

Bowman BA and Russell RM (2001) Present Knowledge in

Nutrition, 8th edn. Washington, DC: International Life

Science Institute Press.

Groff JL and Gropper SS (2000) Advanced Nutrition and

Human Metabolism, 3rd edn. Belmont, California:

Wadsworth.

O’Dell BL and Sunde RA (eds) (1997) Handbook of Nutri-

tionally Essential Mineral Elements. New York: Marcel

Dekker.

Shils ME, Olson JA, Shike M and Ross AC (1999) Modern

Nutrition in Health and Disease, 9th edn. Baltimore,

Maryland: Williams & Wilkins.

COFFEE

Contents

Green Coffee

Roast and Ground

Instant

Analysis of Coffee Products

Decaffeination

Physiological Effects

Green Coffee

R J Clarke, Donnington, Chichester, West Sussex, UK

Copyright 2003, Elsevier Science Ltd. All Rights Reserved.

Introduction

0001 Green or raw coffee comprises green coffee beans;

though, in trading practice, it may also contain

small amounts of extraneous matter, derived from

the harvested and processed coffee cherry and other

foreign matter such as stones.

Classification of Green Coffee Beans

0002A green coffee bean, as defined in the International

Standard, ISO 3509–1989 is ‘a commercial term des-

ignating the dried seed of the coffee plant.’ The coffee

COFFEE/Green Coffee 1481

plant or tree (not shrub) belongs botanically to the

Coffea genus in the family Rubiaceae, with subdiv-

isions and some 80 separate species, of which only

two species are commercially important for green

coffee; these are C. canephora (known in the trade

as C. robusta), and C. arabica L. In each of these two

species, there are a number of true botanical varieties,

but also cultivars, developed by horticultural research

and used in plantations for various agronomic advan-

tages. In recent years, a number of interspecies

hybrids have been developed, notably arabusta in

the Ivory Coast, from the crossing of the arabica

and canephora (robusta) species, but also with other

lesser-known species growing wild in the hope of

conferring advantage in respect of disease resistance,

etc. None of these hybrids has yet developed much

commercial success. Two particular ‘original’ var-

ieties of arabica have been generally recognized, C.

arabica var. arabica (syn. var. typica)andC. arabica

var. bourbon. Cultivars are usually intraspecific by

breeding/selection, such as caturra, mundo novo and

catuai in Central/South America amongst the arab-

icas. Varieties in the C. canephora species are less

precise, originally found in Africa; but C. canephora

var. kouillensis is important and planted also in

Indonesia and latterly in Brazil (where it is known

as Conillon robusta); and also C. canephora var.

nganda, especially found in Uganda. Whilst these

varietal/cultivar names are not normally used in the

trade, the different coffee types will contribute, along

with other factors, to differences in flavor quality

(after roasting/brewing).

0003 Genetically speaking, most of the coffee species are

diploid, as is C. canephora, but C. arabica is tetra-

ploid, that is, arabica has 4 11 ¼ 44 chromosomes

in its genome, unlike C. canephora, which has 22.

This phenomenon has given rise to problems in inter-

specific breeding. Arabica plants are self-pollinating,

though they can be crossed, whereas canephora

(robusta) plants are self-sterile and require cross-

pollinating for seed development. Robusta plants

are generally propagated by use of cuttings (Fr.

bouterage), whereas arabica plants are generally

grown from seeds in nurseries, and then trans-

planted. These two species differ in their optimal

environment for growing. Robusta will grow at low

altitudes, will tolerate high temperatures and heavier

rainfalls, and requires a higher soil humus content

than arabica, and is generally more resistant to dis-

eases and pests (hence its common name). Whilst

arabica is grown at higher altitudes (with quality

connotations in respect of height above sea level) the

plants are particularly susceptible to frost damage,

which can occur from time to time, particularly in

Brazil.

0004In general, coffee plants are only grown in those

countries between the tropics. Arabica is generally

believed to have originated in Ethiopia, and was

first cultivated for large-scale export from the

Yemen in about 1600 by the Turks. From the

Yemen, seedlings were transported by Europeans to

other parts of the world, so that it is now found

mainly in Central/South America, and also in India,

Kenya, Tanzania, and other countries. Robusta de-

rives from the rain forests of Central Africa, but was

only really discovered and commercialized from

about 1880. It is now mainly grown in plantations

in West Africa, and also in Uganda and Indonesia.

0005The flavor quality (after roasting/brewing) of ro-

busta is generally considered to be inferior to arabica.

It is certainly less expensive per unit weight of green

coffee, and now constitutes about 25% of the world

trade (imports into consuming countries). Its particu-

lar characteristics have been found favorable in the

manufacture of some instant coffees, but robusta is

also widely consumed as regular brewed coffee in

countries such as France, Italy, and Spain, and often

features in espresso coffees.

0006A further classification of coffee beans relevant to

both arabica and robusta coffee is into (1) flat beans,

a term characterizing the majority of beans produced,

with their single flat side with a central cleft, and (2)

peaberries, which are small rounded beans resulting

from a false embryony within the original cherry. The

latter have a specialty roaster interest, as do so-called

Maragogype, with an abnormally large-size arabica

bean, found in some parts of Brazil.

0007A further basis of classification is described in the

next section.

Green Bean Processing

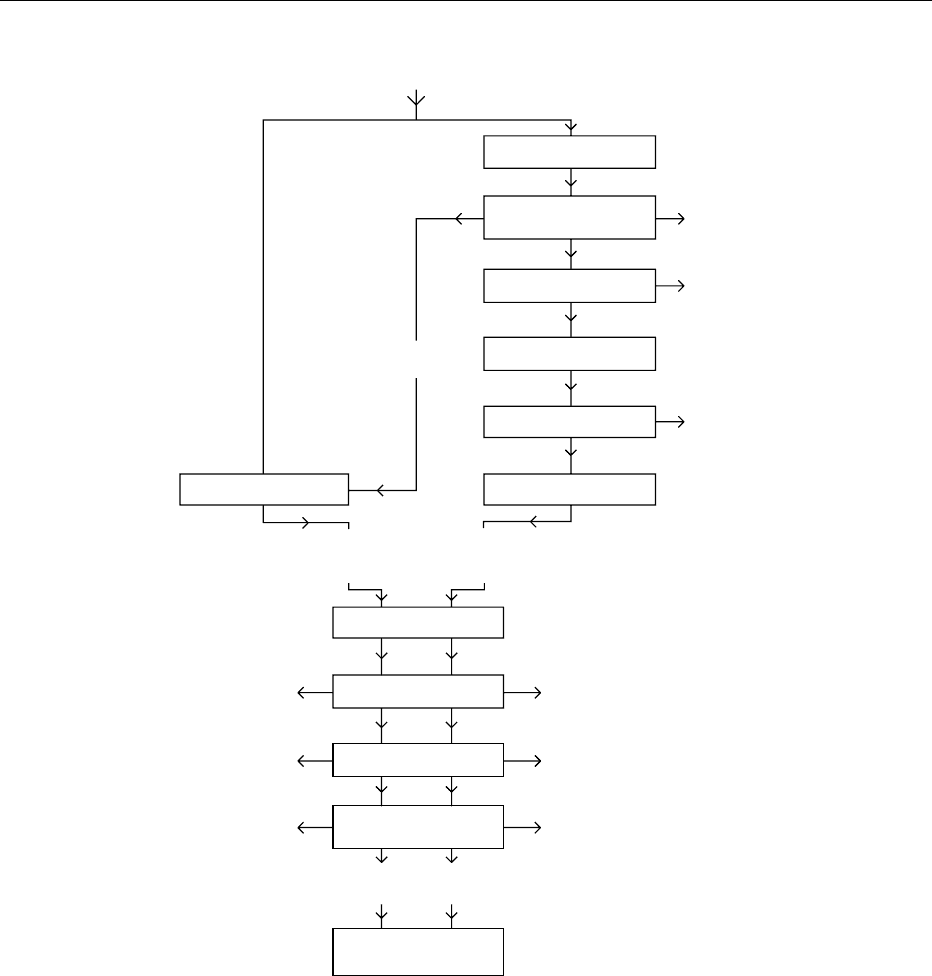

0008Since coffee is originally harvested in the various

growing countries, as ‘cherries’ or ‘berries’ with a

fleshy interior usually carrying two seeds, and an

outer skin, a sequence of operations is carried out in

those same countries, in order to remove their seeds

and present them as beans (dried seeds) or the ‘clean

coffee’ of commerce. Figure 1 illustrates the sequences.

Removal of Beans from within Coffee Cherries

0009Two procedures have been developed – one, called

dry processing, and the other wet processing (for

washed and pulped coffee). The first, also in historical

order, requires the sun-drying of the coffee cherries

laid out in layers (about 30 mm thick), which need to

be periodically turned over during a period of some 3

weeks, until the moisture content is brought down at

least below 13% w/w. This time period may be sub-

stantially reduced by the alternative use of specialized

1482 COFFEE/Green Coffee

machine air driers. This type of process is used for

nearly all robusta coffee production in the world, but

it is still used for most of the arabica coffee in Brazil

and also in Ethiopia and Haiti. The product is now in

the form of so-called husk coffee, that is, dried coffee

cherries, carrying the dried seeds and all outer

covering, which await the next stages known as

‘curing,’ usually carried out at a central large-scale

curing station, which takes in consignments from

various outlying plantations, both large and small.

In curing, after cleaning, the beans are first separated

from their outer coverings by dehusking machines,

based upon a screw principle, of which there are a

number of commercial designs. The final presentation

as clean coffee is described in a subsequent para-

graph. (See Drying: Drying Using Natural Radiation.)

0010The second procedure, known as wet processing, is

more sophisticated than that of the first. In this pro-

cedure, it is important that the coffee cherries be first

graded for ripeness, preferably by harvesting only

those judged to be ripe and of a red skin color;

water-flotation methods may be used for those

Dry

processing

Drying

Dried

cherry

coffee

Dry

parchment

coffee

Wet

processing

Reception

Flotation

cleaning

Pulping Pulp

Fermentation

Washing

Drying

Mucilage

Stones/

dirt

Harvested

coffee

berries

Floaters

Cleaning

Curing

Hulling

Size grading

Sorting

(density/colorimetric)

Green coffee

(flat beans, peaberries)

Storage

Bagging-off

Husks

Undersize Oversize

Triage/waste Triage/waste

Parchments

(hulls)

fig0001 Figure 1 Flow sheet illustrating the stages of wet and dry processing. Reproduced with permission from Clarke RJ and Macrae R

(1987) Coffee, vol. 2. Technology, p. 2.

COFFEE/Green Coffee 1483

overripe cherries and dried on the tree, but not under-

ripe cherries, which are equally, if not more, undesir-

able. These cherries are then fed into pulping

machines of various commercial designs, which tear

off and separate the skins and fleshy pulps (exocarp

and mesocarp, respectively) in the presence of much

water. Such machines will, however, leave a portion

of the mesocarp, a mucilaginous layer adhering to the

pericarp or a parchment layer directly surrounding

the beans. The next stage in the process is therefore a

means of removal by firstly loosening with fermenta-

tion, which is carried out in tanks. There are variants

of detail of this operation in different countries,

according to local ‘know-how,’ climatic conditions,

and location height above sea level. Fermentation

proceeds through the action of microorganisms or

enzymes from within the semipulped coffee, over a

period of about 24 h under either wet or dry (no

added water) conditions. Care has to be taken that

excess acidity does not develop, nor that of taints.

After a dry fermentation, a water soak has been

recommended (Kenya). The loosened mucilage is

then completely washed off, by use of large quantities

of water as the product is allowed to flow along long

concrete channels, after which it is drained of excess

water. An alternative system to pulping/fermentation/

washing uses the Aquapulper; the manufacturer

claims it will achieve all these operations within one

machine. The resulting product is now known as ‘wet

parchment coffee,’ which has to be dried. Air-drying

is usually practised, that is, the parchment coffee is

laid out on supported trays, with movable coverings

that can be used during the hottest hours of the day,

or again during cold nights. The drying time will be

between 10 and 15 days to reach a desired moisture

content of 11% w/w. Alternatively the parchment

coffee may be machine-dried in a shorter time, or

for part of the time. In either method, great care is

necessary for quality reasons, and optimal conditions

have been the subject of much study in research sta-

tions in Kenya, Colombia, and elsewhere, with many

published papers. It is now necessary to remove the

dry parchment layer to uncover the beans, by hulling

machines similar in principle to those used in the dry

process, already described, though the percentage

amount of dried coverings to be disposed of is clearly

much less.

Preparation of the Clean Coffee for Export

0011 The next stages of curing from either of the two

processes described above, after cleaning, involve

firstly a size-grading stage, that is, by machines with

rotating cylinders on a horizontal axis, fitted along

their length with punched hole screens, of about three

different hole sizes. Size grading is particularly needed

for dry processed coffees (Figures 2 and 3). Each of the

size grades is then subjected to a series of sorting

operations. The first is a density separation, which

enables residual extraneous matter originating from

the cherry, such as pieces of husk, parchment, etc.

(dependent upon the wet or dry process previously

used), abnormally light density beans, and indeed of

foreign matter, to be removed as much as possible.

Separation methods generally rely on air levitation

principles, for which a number of machine types are

available. A second sorting based upon the color of

beans has traditionally relied upon hand-picking as the

beans move along a traveling belt, which also enables

some other defects such as malformed beans and other

residual defective matter to be removed. Electronic

sorting is, however, becoming very widely used, with

monochromatic light used to sort out, in particular,

‘black beans,’ regarded as especially unfavorable to

quality, which may otherwise occur frequently in dry

processed coffees. The target is to achieve substan-

tially less than 1% by weight of black beans (or

fewer than five per 300 g sample). Electronic sorting

may also use multichromatic light, which enables a

wider range of discolored beans to be discarded,

though such sophisticated machines are more usual

in the consuming countries. For wet processed arab-

ica there has also been a considerable growth in the

8.00(20)

7.50(19)

7.10(18)

Grade II

Grade I

Grade III

6.70(17)

6.30(16)

6.00(15)

5.60(14)

5.00(13)

4.75(12)

4.00(10)

20 50

Cumulative amount retained on screen by weight (%)

Aperture diameter (mm) (screen number)

94 99

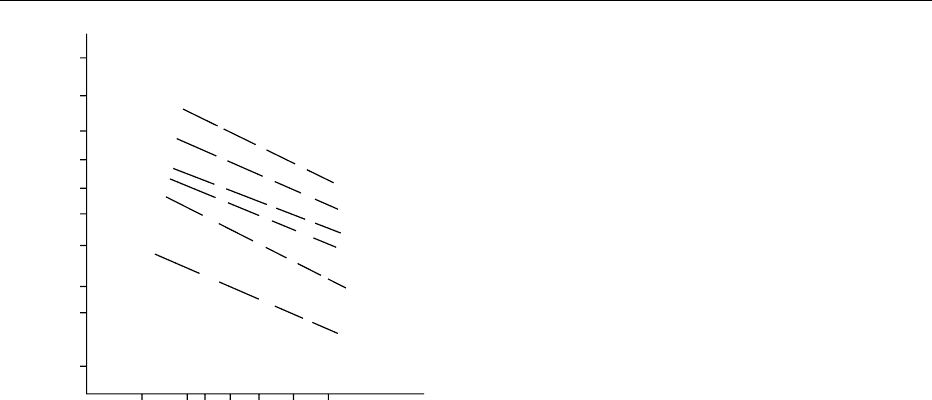

fig0002Figure 2 Typical screen analyses for different size grades of

Ivory Coast robusta green coffee beans according to specifica-

tions (including allowable tolerances), plotting percentage cumu-

lative amount by weight (probability scale) held at each screen

size (aperture diameter, mm) for screens according to ISO 4150.

o—o, actual experimental data for grade II sample. Reproduced

with permission from Clarke RJ and Macrae R (1987) Coffee,

vol. 2. Technology, p. 41.

1484 COFFEE/Green Coffee

use of sorters, in the producing countries, based upon

fluorescence differences, which are designed to

remove any so-called ‘stinker beans,’ difficult to

detect easily otherwise but especially undesirable to

flavor quality if present, even in very small numbers.

0012 The object of all the foregoing stages is therefore to

provide ‘clean coffee’ at the right moisture content,

which can then be bagged for export (or internal

consumption) and documented according to origin,

type, and grade. Commercial green coffees are further

subdivided into wet-processed arabicas, known as

‘milds’ in the trade, dry-processed arabicas, and

robustas (dry-processed).

Marketing, Grades, Shipping, and Storage

0013 The marketing of coffee is a complex commercial

operation, with an underpinning by the International

Coffee Organization, based in London, which, for

example, through international governmental agree-

ments in force from time to time can organize quota

systems for price stability. For the various green

coffees under their control for export, the marketing

authorities in different countries issue specifications,

which may be either detailed or brief, without neces-

sarily direct reference to flavor (i.e., when roasted/

brewed). Test methods are available, many from the

International Standards Organization on representa-

tive samples from consignments.

Grades and Types of Green Coffee

0014An important grade criterion is that of bean size

(range), as can be characterized by a screen analysis

using a number of internationally recognized screens

with specific hole diameters (ISO 4150–1980, revised

1991). Different shorthand terms are used to express

bean size distribution, e.g., letters such as A, B, C,

etc., in Kenya, words (large–small with intermedi-

ates) in Brazil, and numbers (1, 2, 3) in robustas

from the Ivory Coast. From Colombia, virtually

only one size grade (excelso) is exported, all defined

on screen no. 15 (6 mm) and most through no. 18

(7.5 mm hole diameter).

0015A second criterion is that of type, specifically de-

fining the number of defects present per sample, that

is, defective beans of various kinds, extraneous and

foreign matter. Different systems are in force, though

most adopt a black bean equivalency system, where

one black bean per 300-g (or 1-1b) sample equals one

defect, and where other kinds of defect are assessed as

numbers required to equal one black bean. Total

numbers of defects define the type, which may be

expressed in words, e.g. supe

´

rieure in the Ivory

Coast for robusta, or terms, e.g. NY numbers (1–8)

in Brazil. Such type numbers are not, however, used

for wet-processed coffees from Kenya, Colombia, and

some other countries, where the number of defects in

most of their exported coffee is very small (e.g., < 13

per 300-g or 1-lb sample). Numbers of particular

defects such as moldy or insect-damaged beans

are rigorously controlled in many countries (both

importing/exporting); especially in the USA by the

Federal Drug Administration with legislative backing,

primarily for health and hygiene reasons.

0016A specification will, of course, refer to country of

origin, maybe also growing area/port of embarkation

and species/green bean processing method where this

may be otherwise uncertain; and whether new crop or

old crop. Purchase or otherwise may be primarily on

the basis of exchange of samples, where the oppor-

tunity of inspecting for flavor quality and appearance

is available.

Shipping and Storage

0017Some storage of green coffee is inevitable at various

times from source to roaster, including of course

during transit by ship (whether in bags in holds, or

now more usually bags or loose in containers). It is

generally recognized that green coffee should not be

allowed to reach a moisture content in excess of 13%

w/w; otherwise, mold growth will start to occur,

which increases rapidly with increasing moisture con-

tent, causing flavor deterioration and the possibility

of mold toxin formation. It should be noted that

Bold − Large

Good − Bold

Medium − Good

Medium

Small

Good

8.00(20)

7.50(19)

7.10(18)

6.70(17)

6.30(16)

6.00(15)

5.60(14)

5.00(13)

4.75(12)

4.00(10)

1102045

Cumulative amount retained on screen by weight (%)

Aperture diameter (mm) (screen number)

70 90 98

fig0003 Figure 3 Typical screen analyses for different size grades of

Brazilian arabica green coffee beans according to specifications

(including allowable tolerances). Percentage cumulative amount

by weight held at each screen size (screens according to ISO

4150) plotted on a probability scale. Reproduced with permission

from Clarke RJ and Macrae R (1987) Coffee, vol. 2. Technology,

p. 43.

COFFEE/Green Coffee 1485