Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

the electric motor is ubiquitous and consumes 40–

45% of all electrical energy generated. Most of this

energy is consumed by large industrial electric drives,

but nonetheless an increasing proportion is consumed

by small electric motors used in domestic appliances,

for example, in refrigerators which operate continu-

ously. Regardless of the motor application there is

pressure to improve electric motor efficiency as peo-

ple and governments become more aware of the con-

sequences of global warming, due to the emission of

the greenhouse gas, CO

2

, from large coal-fired power

stations.

Electric motors are present in many household

products (for the purposes of this section ‘‘domestic’’

is defined as any product that is found in the home).

Products containing electric motors can be grouped

according to their domestic application area and

a list, by no means exhaustive, includes: laundry—

washing machine and clothes dryer; kitchen–dish-

washer, microwave oven, fan-forced convection

oven, refrigerator, food blender, electric knife, gar-

bage disposal unit, mixmaster, etc; bathroom—hair-

dryer, electric tooth brush, hair clippers, electric

shaver, etc; entertainment—videorecorder, CD play-

er, hi-fi system, camcorder, walkman, camera, etc;

home study—personal computer, printer, photocop-

ier, facsimile machine, etc; general household—

vacuum cleaner, exhaust fans, ceiling fans, swimming

pool and spa pumps, air-conditioner, fans in gas and

electric heating systems, etc; and garage—electric

drills, saws, routers and grinders, electric screwdriver,

electric lawn mower, edge clipper, garden shears, ga-

rage door/gate opener, etc.

Some products or appliances may contain as many

as four or five individual motors, for example, a

camcorder, and where there is a motor there is likely

to be power and control electronics, for example, a

switch-mode power supply that incorporates magnetic

components. Not included in domestic appliances is

the family automobile, which may contain up to 40 or

even more electric motors. The use of magnetic ma-

terials is not just confined to motors, as they are used

in speakers in televisions and hi-fi systems, holding

devices, water-meters, watt-hour meters and fluores-

cent lighting ballasts.

1. Motor Technology

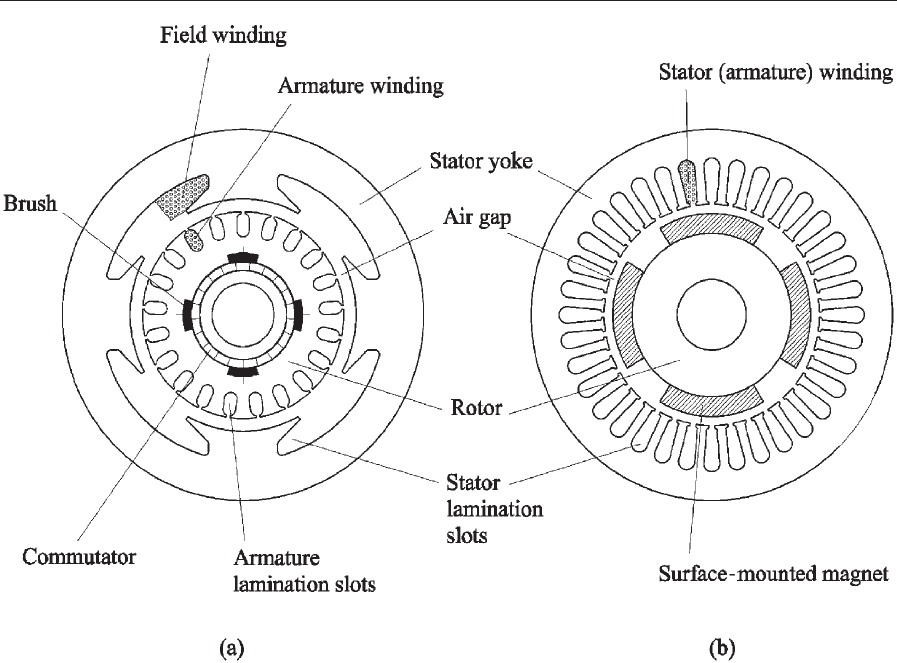

A conventional brushed d.c. electric motor can be

viewed as having three key components: a field sys-

tem, which usually consists of a winding around teeth

on a stator yoke; an armature, consisting of a series

of coils wound in slots on a rotor; and a commutator,

for making the electrical connection to the armature

coils (Hamdi 1994). The stator and armature lami-

nations are made from a soft magnetic material, usu-

ally low-loss silicon steel laminations, and are part of

the magnetic circuit which carries and guides the

magnetic flux in the machine. In a permanent magnet

machine the field system uses permanent magnets

rather than producing the field by passing current

through coils.

The replacement of the wound field system by per-

manent magnets results in a significant improvement

in motor efficiency, as no electrical energy is used in

field production. The motor can then be turned in-

side-out with the field magnets being attached to the

rotor, a multiphase armature winding on the stator,

and the commutator replaced by electronic switching

devices which switch the current through the stator

windings (see Fig. 2). This configuration has the ad-

vantage of improved thermal performance, as im-

proved cooling is obtained by having the high-current

stator winding in good thermal contact with the mo-

tor case. Motors of this type are known as permanent

magnet brushless d.c. motors or just brushless d.c.

motors (Hughes 1993, Gieras and Wing 1997).

Modern permanent magnet brushless d.c. motors

have the advantages of high torque or power per unit

volume, improved efficiency, better dynamic response

(due to the low inertia of the rotor), reduced volume,

reduced weight, mechanical simplicity and reliability

(as there are no brushes or commutator), and quiet

operation (Hanitsch 1989). These improvements did

not happen overnight, but are the result of advances

in materials science over the past 30 years, particu-

larly the development of rare-earth permanent mag-

nets (Sm

2

Co

17

and Nd

2

Fe

14

B) (see Rare Earth

Magnets: Materials), and new soft magnetic materi-

als, such as amorphous or glassy metals (see Amor-

phous and Nanocrystalline Materials). In parallel with

these developments in materials science there have

been major advances in magnetic circuit design, using

computational methods based on finite-element

techniques, and a revolution in semiconductors, re-

sulting in low-cost microprocessors and digital signal

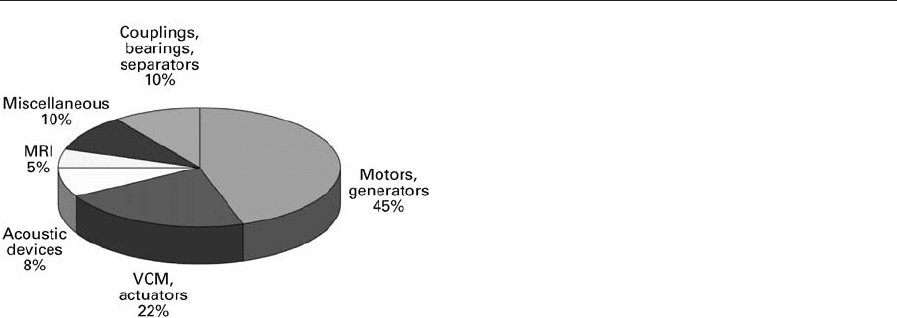

Figure 1

Expected application of Nd

2

Fe

14

B in Europe for 1995

(Krebs 1995).

470

Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applications

processors for motor control, and high-power switch-

ing devices.

Losses in electric motors have three main

sources:

*

copper losses or I

2

R losses, which are due to the

finite electrical resistance of the copper wire used in

the windings (in a brushed machine this also includes

losses from brush contact resistance);

*

magnetic or iron losses from both magnetic

hysteresis losses in the soft magnetic components and

eddy currents; and

*

friction and windage losses from bearing fric-

tion, brushes, if present, and the rotor peripheral

speed (Hamdi 1994).

The design of a high-efficiency motor requires

minimization of the losses, and may be achieved by

the use of novel motor topologies, good magnetic

circuit design, and judicious choice of materials, for

example, low-loss electrical steels. Innovative motor

designs may not use any iron at all; an example is

an axial flux in-wheel motor developed for a solar

powered car that has an efficiency of 98% (Ramsden

1998).

Motors used in domestic applications range in

power from a fraction of a watt, or a few watts, to

about 2 kW, have an output torque in the range

from a few mNm to about 10 Nm, an efficiency of 60

to 70%, and an operational speed from a few rpm to

25 000 or 30 000 rpm. No one motor type satisfies

all these power, torque, and speed requirements. A

variety of motor types is used, each with performance

characteristics to match the application. For exam-

ple, a vacuum cleaner motor is required to operate at

high speed, and may be only used for an hour per

week.

With this intermittent operation there is no great

need for high reliability or high efficiency; rather,

manufacturers aim for a motor of minimum cost. The

situation is somewhat different with a washing ma-

chine. Here the motor has two extremes of operation;

it is required to operate at low speed with high torque

for the wash cycle and high speed with low torque

Figure 2

Schematic showing (a) a wound field brushed DC motor and (b) a brushless permanent magnet motor.

471

Magnetic Mater ials: Domestic Applications

during the spin cycle, to remove water from the

clothes. On the other hand, for a refrigerator that

operates continuously or a battery-powered hand-

held drill there is an advantage in having a motor of

high efficiency as this will minimize energy consump-

tion, and for the drill it will give a longer period of

use between battery charges.

Generally most domestic appliances are low-cost

items, and the motor is usually chosen with this in

mind. A common motor type used in intermittently

operated hand-held appliances is the brushed univer-

sal motor (it has the same configuration as a brushed

d.c. motor). Universal motors are made in a variety

of sizes, are very low cost, and have the advantage

of a simple controller for variable speed operation,

though they are noisy at high speeds. Universal mo-

tors are used in hair-dryers, food blenders, vacuum

cleaners, electric drills, saws and routers, mixmasters,

etc. Induction motors tend to be favored in constant-

speed continuous operation situations, for low noise

and for their low-cost: for example, in fans, com-

pressors in air-conditioners and refrigerators, clothes

dryers, pool and spa pumps, etc.

Permanent magnet motors may use either hard-

ferrite or rare-earth permanent magnets (very rarely

AlNiCo), with the former often used in small pumps

in washing machines and dishwashers, and in com-

pact low-noise fans and the latter where the features

of high efficiency and high power/torque per unit

volume are required, e.g., video-recorders, computer

disk drives, CD players, camcorders, cameras, fac-

simile machines, battery-powered screw drivers, and

drills. The situation with washing machines is inter-

esting and reflects market diversity. In Europe

frontloading washing machines dominate and tend

to use brushed universal motors, while in the USA

front-loaders may use a switched reluctance motor.

For toploading machines, which are popular in the

USA and Australia, both induction motors and

direct-drive ferrite permanent magnet motors are

used.

In domestic applications hard ferrite magnets

dominate, with only limited use of rare-earth perma-

nent magnet motors. More widespread use of rare-

earth permanent magnet motors will occur when

some, or all, of their advantages of compactness,

high efficiency, high torque/power per unit volume,

and improved dynamic response are required by the

particular product. Domestic applications are highly

cost-sensitive, and manufacturers are constantly

seeking the lowest cost solution, which inhibits the

take-up of motors using rare-earth permanent mag-

nets as they are often of higher cost compared with

competing motor types. This is changing as rare-

earth magnet prices decrease, motor numbers in-

crease, and the technical advantages of rare-earth

permanent motors in particular applications become

more apparent.

2. Soft Magnetic Materials

In an electrical machine, the magnetic losses or core

losses are due to the soft magnetic material operating

in a time-varying magnetic field. Core losses (see

Magnetic Losses) are made up of eddy current losses

that arise from circulating electrical currents induced

in conducting materials (the electrical steel used in the

stator and copper used in the motor windings) and

magnetic hysteresis losses which are proportional to

the enclosed area of the B–H loop of the particular

material. The characteristics required of the soft

magnetic material are:

*

high saturation induction to minimize weight

and volume of the iron parts;

*

high permeability for design of a low reluctance

magnetic circuit;

*

low coercivity to minimize hysteresis losses; and

*

high resistivity to minimize eddy current losses

(minimization of eddy currents is also achieved by

using thin laminations that are covered by a thin in-

sulating layer to provide interlaminar insulation).

These desirable magnetic properties are not found

in one material, as there are many factors that affect

the magnetic properties. The magnetic properties of a

material may be tailored by the addition of chemical

elements, mechanical working of the material, and

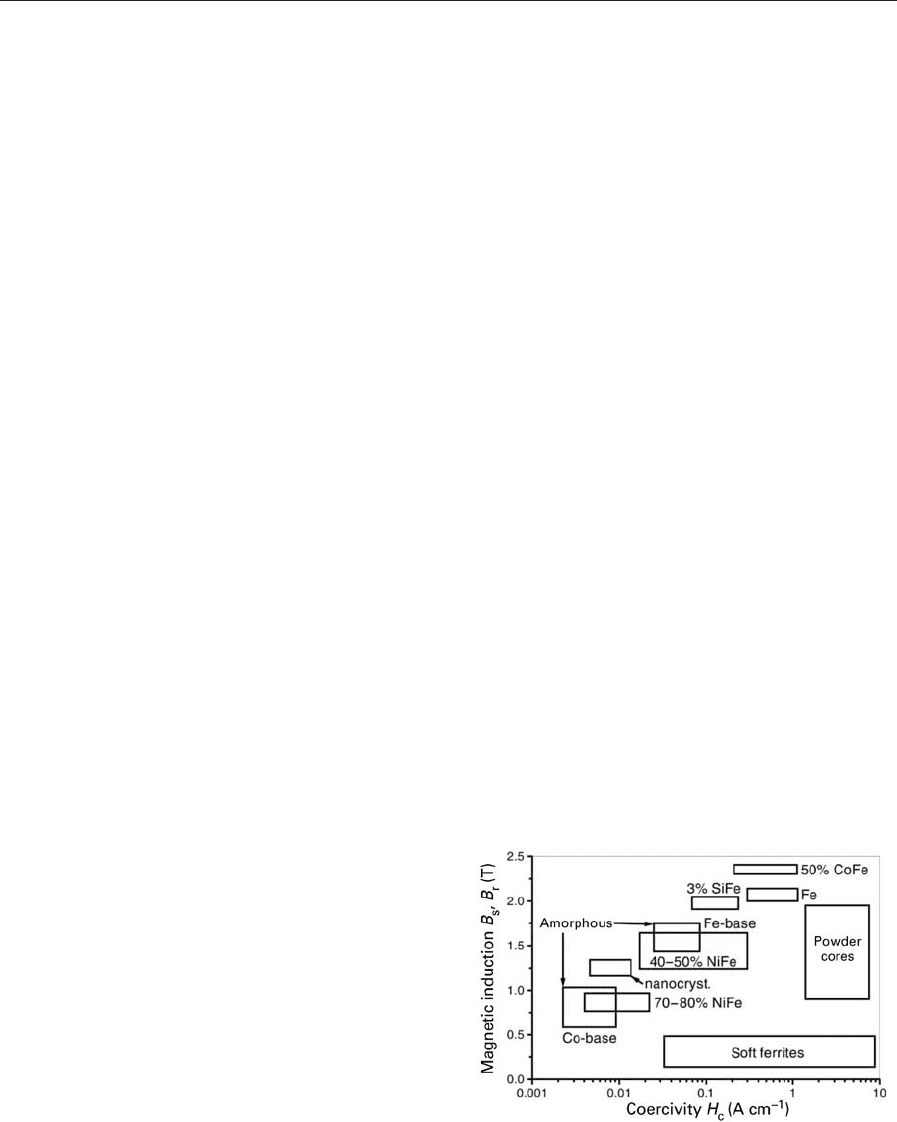

heat treatment. The characteristics of a range of soft

magnetic materials are shown in Fig. 3 and Table 1

(for reference data see Warlimont 1990 and Clegg

et al. 1993).

2.1 Silicon–Iron Electrical Steels

The most common soft magnetic material used in

electrical machines is silicon–iron electrical steel (see

Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic Properties) in the

form of thin laminations. The addition of silicon to

soft iron results in a significant decrease in coercivity,

Figure 3

Typical property ranges of soft magnetic materials.

472

Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applications

a slight decrease in saturation magnetization, and an

increase in resistivity. There are two distinct catego-

ries of electrical steels: nonoriented isotropic products

with silicon contents in the range 1–3.5%, and grain-

oriented anisotropic products which contain 2.9–

3.15% Si ( þAl). Silicon levels above 3.5% result in

the steel becoming very brittle and hard to work.

Oriented steels have the lowest core loss (see Table 1)

and are used in transformers, whereas nonoriented

steel is used in electrical machines as there are varying

flux directions.

Domestic appliances are dominated by low-cost

universal and induction motors, with efficiencies of

60–70%. The quest for low cost results in motors that

use lower-quality nonoriented electrical steels and

thicker laminations (typically 0.65 mm), the latter re-

sulting in a reduction in the number of stamping op-

erations necessary to produce the stator lamination

stack.

2.2 Iron–Cobalt Alloys

Iron–cobalt alloys (such as Permendur 49, 49Co–

49Fe–2 V) have the highest saturation magnetization

of all the soft magnetic materials (see Fig. 3). They

have the disadvantage of a much higher cost than

silicon–iron steels, but are used in applications where

it is advantageous to reduce size and weight. Iron–

cobalt alloys are used in aircraft generators, some

400 Hz motors, and active magnetic bearings.

2.3 Amorphous or Glassy Metals

Amorphous metals (see Amorphous and Nanocrystal-

line Materials) are made from alloys whose constit-

uents may include Fe, Ni, and Co and a metalloid or

glass former such as silicon, boron, or carbon. A

typical amorphous metal, offered for sale by Allied-

Signal Inc, USA, is METGLAS 2826, which has the

composition Fe

40

Ni

40

P

14

B

6

. Amorphous metals are

very thin, of the order of 0.025 to 0.04 mm. They have

the lowest coercivity of all the soft magnetic materials

and a higher resistivity than electrical steels, resulting

in a material with the lowest core loss (see Table 1).

There is a number of issues regarding the use

of amorphous metals in electrical machines. The

very desirable feature of low coercivity is counter-

balanced by the lower saturation magnetization,

E1.5 T compared with E2 T in silicon–iron steels.

The cutting and forming of amorphous metal lami-

nations is expensive due to increased tool wear from

their hardness (over C-80 Rockwell), and being very

thin there is a greater number of stamping opera-

tions, and the material does not stack as well. Amor-

phous metals have been used in electrical motors

where high efficiency is all-important (494%), but it

is in distribution transformers where the material is

proving most beneficial (DeCristofaro 1998).

2.4 Soft Magnetic Composites

Soft magnetic composite (SMC) materials are made

from bonded iron powders. The iron powder is

coated with an insulating layer and pressed into a

solid material using a die before final heat treatment

to cure the bond. It is not a powder metallurgy proc-

ess where sintering is used. SMC materials are rather

new and have a number of advantages. The material

is isotropic, enabling the design of magnetic circuits

that have three-dimensional flux paths, and since

there is an insulating layer between the iron powder

particles, losses due to eddy currents are minimized.

The material can be used at frequencies up to

100 kHz, and the cross-over point for core loss for it

and 3% silicon steel (0.5 mm thick) is about 400 Hz,

where at 1.5 T the loss for both materials is about

90 W kg

1

. The main advantage of the material may

Table 1

Properties of some common soft magnetic materials.

Grade

Thickness

(mm)

Nominal silicon

content (%)

Resistivity

(mO m)

Core loss at

1.5 T and 50 Hz

(Wkg

1

)

Low-loss Si–Fe steel, nonoriented

Transil 300-35-A5 0.35 2.9 0.48 2.95

Losil 400-50-A5 0.50 2.4 0.44 3.60

Losil 800-65-A5 0.65 1.3 0.29 6.5

Low-loss Si–Fe steel, oriented

Unisil 35M6 0.35 3.1 0.48 1.00

Permendur 49 (Co49/Fe49/V2) 0.35 NA 0.40 3.0

METGLAS 2605SA1 0.025 NA 1.3 0.16

a

SMC (iron powder) NA NA NA 10

a Measured at 1.4 T.

473

Magnetic Mater ials: Domestic Applications

be in low-cost manufacture, as parts can be made to

net shape, using highly-automated mass production

methods. The main disadvantage of the material is its

high core loss at 50 Hz when compared with silicon–

iron electrical steels. Nonetheless, a number of

prototype transverse flux and claw-pole electrical

machines have been made using SMCs (Jack 1998).

2.5 Soft Ferrites

The magnetically soft ferrites (see Ferrites) have

the general chemical formula MeFe

2

O

4

, where Me

is most commonly MnZn (MnZn ferrite) or NiZn

(NiZn ferrite), and have the cubic structure of the

mineral spinel. The properties of the soft ferrite may

be further adjusted by additions of Mg, Cu, or Co, or

a mixture of these. The soft ferrites have the general

characteristics of low coercivity, high permeability,

and high resistivity.

The high resistivity results in negligible losses due

to eddy currents, enabling the material to be used at

high frequencies (b1 MHz). Generally the NiZn fer-

rites have a higher resistivity than the MnZn ferrites,

but a lower saturation induction. The soft ferrites are

manufactured in a range of core shapes, rings, pots,

and E and C cores, for use in inductors and trans-

formers. Their use is primarily in compact electronic

power supplies and telecommunication components.

Their relatively low saturation induction makes them

unsuitable for use in power or high-flux transformers.

Another class of soft ferrites, the iron garnets with

the general formula R

3

Fe

5

O

12

, where R is a rare-

earth, usually yttrium, is used in specialized micro-

wave devices.

3. Hard Magnetic Materials

The role of hard magnetic materials, in particular

high-energy permanent magnets, in electric motors is

replacement of the field winding. In any application,

including motors, there is a multitude of factors that

require consideration to ensure that the optimum

magnet material is selected (Coey 1996a, Kirchmayr

1996). Of importance are:

*

magnetic parameters: remanence, intrinsic co-

ercivity, and magnetic energy product, BH

max

;

*

temperature stability of the magnetic para-

meters;

*

ease of magnetizing the material;

*

ease of forming the magnet into the desired

shape;

*

environmental factors, such as resistance to cor-

rosion; and

*

cost (cost can be treated in a variety of ways,

and includes material cost, cost per unit of magnetic

energy product, and the cost of forming the material

into the desired shape and its magnetization).

Selection of the permanent magnet material im-

pacts on the motor design; for example, a motor us-

ing a hard ferrite has narrow stator teeth, compared

to the wider teeth in a machine using rare-earth per-

manent magnets, where the magnetic flux density is

much higher. It is also desirable for motors that the

magnet material has a linear B–H curve in the sec-

ond, or demagnetizing, quadrant of the hysteresis

loop. Both hard ferrite and rare-earth magnets have

this characteristic, whereas AlNiCo differs by exhib-

iting a highly nonlinear demagnetization behavior.

For the motor designer rare-earth permanent mag-

nets offer the advantages of a high BH

max

, which

reduces the amount of magnet material required, and

high-intrinsic coercivity, which is important if the

motor is to withstand high armature currents, which

could lead to demagnetization of the magnets. Typ-

ical properties for a range of permanent magnet ma-

terials are given in Tables 2 and 3. For detailed

information on magnet types see McCaig and Clegg

(1987) and Coey (1996b); see also Hard Magnetic

Materials, Basic Principles of).

The use of any permanent magnet material in a

particular application is not only governed by the

Table 2

Typical properties of some common permanent magnet materials.

Material Remanence (T) Intrinsic coercivity (kAm

1

) Energy product (kJm

3

)

Sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B 1–1.4 3200–1000 190–380

Sintered Sm

2

Co

17

1.04–1.12 2070–800 200–240

Sintered SmCo

5

0.90–1.01 2400–1500 160–200

Anisotropic bonded HDDR Nd

2

Fe

14

B 0.81–0.87 915–1154 123

Isotropic plastic bonded Nd

2

Fe

14

B 0.4–0.7 1000–600 30–76

Sintered anisotropic AlNiCo 0.72–1.26 1920–610 20–44

Sintered isotropic AlNiCo 0.62–0.84 1190–125 4–18

Hard ferrite, anisotropic 0.36–0.40 180–270 25–31

Hard ferrite plastic bonded anisotropic 0.22–0.30 240–190 15–18

Hard ferrite isotropic 0.22–0.28 230–300 8.5–10

Hard ferrite plastic bonded isotropic 0.1–0.15 180–230 2–4

474

Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applications

magnetic, physical, and chemical parameters, but

also by the cost of the material. Applications and

products are driven by markets, and the success or

failure of a product in a particular market is driven by

cost. The world market for various magnet types is

given in Table 4 (Ormerod and Constantinides 1997),

and it shows that the market is dominated by the low-

cost hard ferrites. Included in Table 4 is the price per

kilogram for various magnet materials. These prices

are at best estimates, and are based on information

from a variety of sources, including Abraham (1995)

and material presented at the 1999 Gorham/Intertech

NdFeB ’99 Meeting (Gorham/Intertech Consulting,

Portland, ME, USA). It is difficult to give accurate

pricing, as this information is often kept confidential

by manufacturers, can be very dependent on quantity

and complexity of the magnet shape, and subject

to market volatility. For example, the advent of low-

cost Nd

2

Fe

14

B from the Far-East has had a consid-

erable impact. Nonetheless, Table 4 does give a guide

to the relative prices. In terms of cost per unit of en-

ergy, both sintered hard ferrite and sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B

are approaching parity (hard ferrite of 27 kJm

3

,

$2.50–3.00 kg

1

, E$0.10 (kJm

3

)

1

and Nd

2

Fe

14

Bof

250 kJm

3

, $30 kg

1

, E$0.12 (kJm

3

)

1

). In recent

years, both sintered and bonded Nd

2

Fe

14

B have

decreased in price, and it appears this trend will

continue as market share increases and Nd

2

Fe

14

B

becomes cost-effective in new applications and

replaces existing magnet materials in current appli-

cations.

3.1 Rare-earth Cobalt Magnets

Sintered and polymer-bonded magnets based on both

the SmCo

5

and Sm

2

Co

17

alloy composition are avail-

able from a variety of manufacturers. The main ad-

vantage of Sm–Co-based magnets is their high Curie

temperature, making them suitable for use in appli-

cations at elevated temperatures, but they suffer from

the disadvantage of high cost. The sintered material

tends to be somewhat harder and more brittle than

Nd

2

Fe

14

B, but it has excellent corrosion resistance.

Sintered Sm–Co magnets are used in applications

where arduous conditions apply, for example, in

motors that are used in oil-wells, high-temperature

automotive sensors, and microwave switches in tel-

ecommunication satellites.

3.2 Neodymium–Iron–Boron (Nd

2

Fe

14

B) Magnets

Nd

2

Fe

14

B magnets are commercially available in a

number of forms—anisotropic sintered and anisotropic

Table 3

Thermal characteristics for some permanent magnet materials (a is the reversible temperature coefficient of the

remanence and b is the reversible temperature coefficient of the intrinsic coercivity).

Material a (%K

1

) b (%K

1

)

Max. operating

temperature

(1C)

Curie

temperature

(1C)

Sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B 0.13 (0.5–0.65) 200 310

Sintered SmCo

5

0.045 (0.2–0.3) 250 720

Sintered Sm

2

Co

17

0.03 0.19 350 825

AlNiCo (0.01–0.02) 0.01–0.03 500 830

Ferrites 0.2 0.3–0.4 300 450

Table 4

World permanent magnet market in 1994 and current prices.

Material Market 1994 (US$ Millions) Price ($USkg

1

)

Bonded Nd

2

Fe

14

B 194 30–100

Sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B 603 30–150

Bonded ferrite 673 2.50–6

Bonded rare-earth cobalt 30 230

Sintered ferrite 1244 2.50–5

Sintered rare-earth cobalt 218 250–300

Other (including AlNiCo) 248 50–80

a

Total 3210

a For cast/sintered AlNiCo.

475

Magnetic Mater ials: Domestic Applications

and isotropic powders for polymer bonded magnets.

Isotropic powders are prepared using a rapid solidifi-

cation method and anisotropic powders by the HDDR

(hydrogenation, desorption, disproportionation, re-

combination) process (Kirchmayr 1996). Projections

suggest a cost of $30 kg

1

for isotropic powder by

2001. Polymer-bonded magnets are formed by either

compression or injection molding, and binders include

nylon 6/6. The great advantage of polymer-bonded

magnets is that complicated shapes and geometries can

be prepared to near-net or net shape using very low-

cost production processes.

For applications requiring magnets of the highest

possible energy product, sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B is the

magnet of choice (see Magnets: Sintered). The thermal

stability of sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B magnets has improved,

with operating temperatures of 200 1C now attainable.

Similar advances have been made in corrosion resist-

ance with the addition of cobalt and other alloying

components. Sintered magnets find uses in applica-

tions that require the best possible performance, for

example, servomotors in machine tools.

Polymer-bonded magnets are the most rapidly

growing section of the permanent magnet market.

The reason for this rapid expansion is the demand

for magnets for computer disk drives. Currently

more than 50% of rare-earth magnets produced

in Japan are used in computer disk drives, and

the world market for computer disk drives is ex-

pected to exceed 250 million units by 2002. There

is also considerable demand for polymer-bonded

magnets for small motors in video recorders, camc-

orders, printers, facsimile machines, office automa-

tion, automotive, and portable drills (Ormerod and

Constantinides 1997).

3.3 Aluminum–Nickel–Cobalt (AlNiCo) Magnets

AlNiCo magnets are manufactured by a powder met-

allurgy process or by casting, and are available in

both isotropic and anisotropic forms. They tend to be

expensive due to the cost of the raw materials, but

they have good corrosion resistance and a very re-

spectable remanence, 1.26 T, when compared with the

value of 1–1.4 T for Nd

2

Fe

14

B. The major disadvan-

tage of AlNiCo is its low coercivity, which creates

problems in handling and its use in electric motors.

For example, removal of AlNiCo magnets from the

magnetic circuit in a small electric motor often results

in their partial, or complete, self-demagnetization. A

consequence of this is that it is usually necessary to

magnetize AlNiCo magnets in situ.

The advantage that AlNiCo has compared with

other commonly used permanent magnets is its excel-

lent temperature stability. It has a reversible tempera-

ture coefficient of remanence of 0.01 to 0.02%K

1

,

compared with 0.13%K

1

for Nd

2

Fe

14

B. The excel-

lent temperature stability of AlNiCo makes it the

magnet of choice for watt-hour meters, ammeters, and

voltmeters. Additionally, AlNiCo magnets are fre-

quently used in small servomotors in aircraft and

military hardware (see also Alnicos and Hexaferrites).

3.4 Hard Ferrite Magnets

In terms of the global permanent magnet market

hard ferrite magnets still dominate. Ferrite magnets

have the stoichiometry BaFe

12

O

19

or SrFe

12

O

19

, the

latter being increasingly used due to its higher co-

ercivity. They are very cheap, as the raw materials

from which they are made are abundant. A further

advantage is their resistance to many chemicals, and

being an oxide they are ideal for use in damp or wet

environments. Isotropic and anisotropic sintered

magnets, and polymer-bonded magnets formed from

the milled powder, are widely available and used

extensively.

The temperature coefficient of the intrinsic co-

ercivity is positive for the hard ferrites, in contrast to

rare-earth permanent magnets, and consequently

there is a risk of demagnetization if the hard ferrite

magnet is exposed to too low a temperature. Hard

ferrite magnets are found in applications ranging

from door seals in refrigerators to small electric mo-

tors used in dishwashers and washing machines (see

also Alnicos and Hexaferrites).

4. Selected Applications

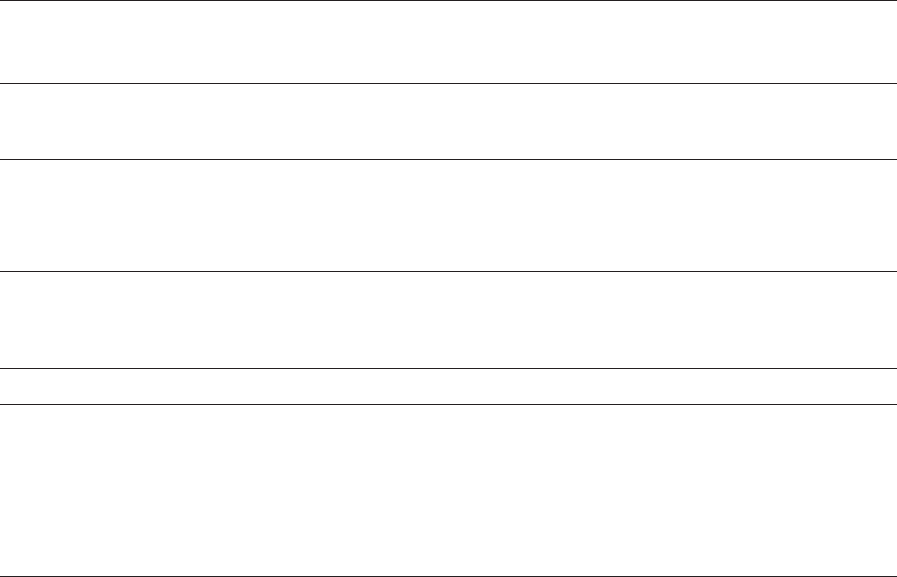

4.1 Computer Disk Drives

Computer disk drives are a prime example of where

performance enhancements are traceable to improve-

ments in permanent magnets. In a fixed disk drive

permanent magnets are used in the spindle motor, in

the actuator that drives the read/write heads (gener-

ally termed the voice coil motor (VCM)), and the

latch assembly (see Fig. 4). Disk drives nowadays

have a 2.5, 3, or 3.5 inch form factor, as emphasis has

switched from miniaturization to making the storage

capacity of the drive as large as possible.

The availability of high-remanence rare-earth mag-

nets has enabled the disk drive designer to reduce

dramatically the size of the VCM, as only a small

volume of magnet material is required, and to de-

crease access times. Disk drives of 41–2 GB capacity

use a high-grade sintered Nd

2

Fe

14

B, showing typically

a remanence of 1.4 T, an intrinsic coercivity of

1,190 kAm

1

, and an energy product of 360 kJm

3

.

One or two magnets may be employed, with a total

weight of 15.5 g, and return poles are made of low-

carbon steel. Spindle motors may use sintered or pol-

ymer-bonded material, with the latter often favored as

it can be easily molded to shape. Spindle motor speed

is important as the higher the speed the shorter the

seek time. High-capacity drives found in file-servers

476

Magnetic Materials: Domestic Applications

have a spindle speed of 10 000 rpm, while drives used

in desktops and notebooks have speeds of 7200 rpm

and 5400 rpm, respectively. Removable cartridge

drives of 100 to 250 MB capacity use linear motors

and polymer-bonded Nd

2

Fe

14

B, to keep their cost

down. On the horizon are compact disk drives for use

in digital cameras. IBM is building a 1-inch 340 MB

hard drive for that application that uses Nd

2

Fe

14

B

magnets.

4.2 White Goods

The domestic appliances most often associated with

motors are refrigerators, washing machines, and dish

washers. On the whole these products appear to have

changed little over the years, but there is increasing

pressure to improve their energy efficiency. In

the USA the Department of Energy mandated a

30% reduction in energy use for refrigerators man-

ufactured after July 2001. An energy-efficient refrig-

erator has been developed in the USA that uses

1.16 kWhd

1

, and part of this efficiency improvement

comes from the use of DC brushless motors (Braham

1997).

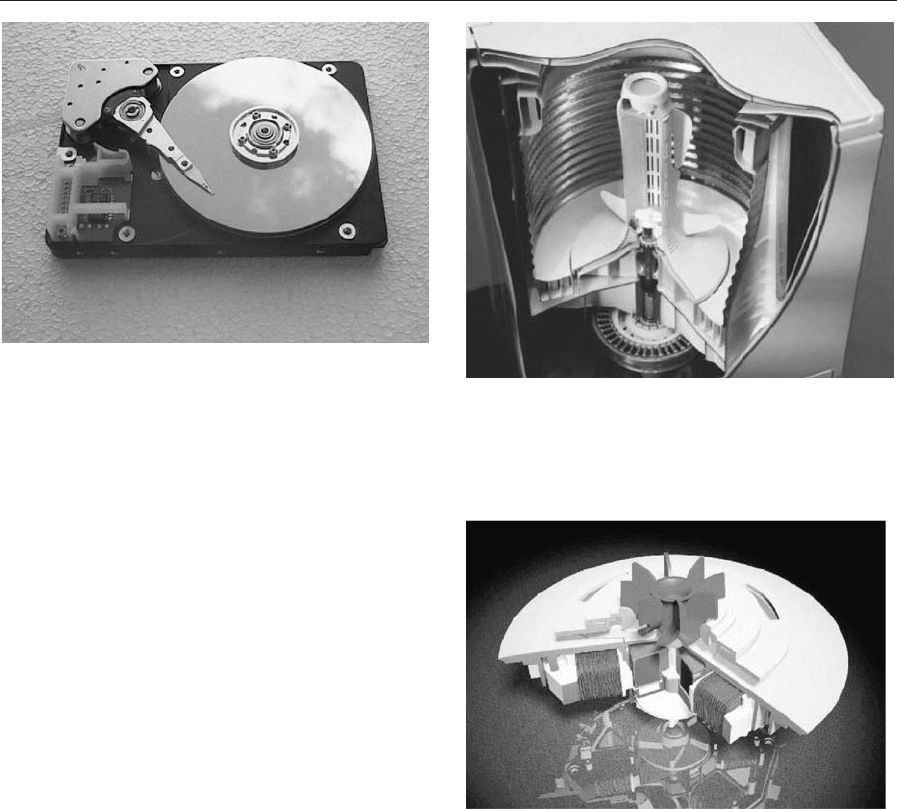

A permanent magnet brushless motor of innova-

tive design is used in a top-loading washing machine

made by Fisher & Paykel, New Zealand, and is

shown in Fig. 5. The motor is of an axially compact

design, approximately 270 mm diameter and 65 mm

long, and uses an outer rotor with hard ferrite per-

manent magnets. The agitator is coupled directly to

the motor. This simplifies the design of the washing

machine, as the gearbox or belt-drive reduction is

eliminated. Fisher & Paykel also make a low-profile

pump motor for use in dishwashers (Fig. 6). Again,

this is a hard ferrite brushless permanent magnet

motor. The magnets are located on the rotor, and the

rotor runs in contact with the water detergent mix of

the dishwasher. This is possible due to the excellent

resistance of ferrite to chemical attack.

5. The Future

Hard and soft magnetic materials will continue to be

fundamental to many domestic applications, and as

improvements are made in their physical, chemical,

and magnetic properties there will be corresponding

product improvements. In the future one can foresee

Figure 5

Cutaway showing direct-drive permanent magnet

washing machine motor. (Photograph courtesy of Fisher

& Paykel, New Zealand).

Figure 4

Hard disk drive unit; the VCM actuator can be seen in

the top left hand corner.

Figure 6

View of a hard-ferrite permanent magnet motor used

in dishwashers. (Photograph courtesy of Fisher &

Paykel, New Zealand).

477

Magnetic Mater ials: Domestic Applications

the ‘‘plastic’’ motor which will be constructed from

an injection or compression-molded soft magnetic

composite stator and polymer-bonded magnets,

bonded directly on the rotor. The great attraction

of such a motor will be its excellent performance and

low cost, as its key components can be manufactured

using low-cost plastic molding methods.

See also: Magnetocaloric Effect: From Theory to

Practice; Magnetic Refrigeration at Room Tempera-

ture; Permanent Magnets: Sensor Applications; Per-

manent Magnet Assemblies

Bibliography

Abraham T 1995 Magnets and magnetic materials: a technical

economic analysis. Int. J. Powder Metall. 31, 133–6

Braham J 1997 Energy efficiency sends appliance designers into

a spin. Machine Des. 40–6

Clegg A G, Beckley P, Snelling E C, Major R V 1993 Magnetic

materials. In: Jones G R, Laughton M A, Say M G (eds.)

Electrical Engineers Reference Book, Fifteenth Edition. But-

terworth Heinemann, Oxford, UK, Chap. 14

Coey J M D 1996a Industrial applications of permanent mag-

netism. Phys. Scr. T66, 60–9

Coey J M D 1996b Rare-earth Iron Permanent Magnets.

Clarendon Press, Oxford, UK

DeCristofaro N 1998 Amorphous metals in electric-power dis-

tribution applications. MRS Bull, (May), 50–6

Gieras J F, Wing M 1997 Permanent Magnet Motor Technol-

ogy. Marcel Dekker, New York

Hamdi E S 1994 Design of Small Electrical Machines. Wiley,

Chichester, UK

Hanitsch R 1989 Electromagnetic machines with Nd–Fe–B

magnets. J. Magn. Magn. Mater. 80, 119–30

Hughes A 1993 Electric Motors and Drives. Newnes, Oxford,

UK

Jack A G 1998 Experience with the use of soft magnetic com-

posites in electrical machines. In: Ertan B, U

¨

ctu Y (eds.)

Proc. Int. Conf. on Electrical Machines. Middle East Tech-

nical University, Ankara, Turkey, pp. 1441–8

Kirchmayr H R 1996 Permanent magnets and hard magnetic

materials. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 29, 2763–78

Krebs J 1995 Hot pressed and die-upset forged magnets. Mag-

news 19–21

McCaig M, Clegg A G 1987 Permanent Magnets in Theory and

Practice, 2nd edn. Pentech Press, London

Ormerod J, Constantinides S 1997 Bonded permanent magnets:

current status and future opportunities. J. Appl. Phys. 81,

4816–20

Ramsden V S 1998 Application of rare-earth magnets in high-

performance electric machines. In: Schultz L, Mu

¨

ller K-H

(eds.) Proc. 15th Int. Workshop on Rare-earth Magnets and

their Applications. Werkstofi-Informationsgesellschaft mbH,

Frankfurt, Germany, pp. 623–42

Warlimont H 1990 Magnetic property assessment: between

physical maximum and economic optimum. IEEE Trans.

Magn. 26, 1313–21

S. J. Collocott

CSIRO Telecommunications and Industrial Physics

Lindfield, Australia

Magnetic Materials: Hard

The prerequisite for permanent magnet materials that

owe their hard magnetic properties to the presence of

magnetocrystalline anisotropy is a crystal structure

of less than cubic symmetry. The tetragonal structure

of the AuCu type (L1

0

) is a well-known example able

to generate uniaxial magnetic anisotropy in com-

pounds in which the magnetic moments are carried

by cobalt, iron, or manganese atoms. As illustrated in

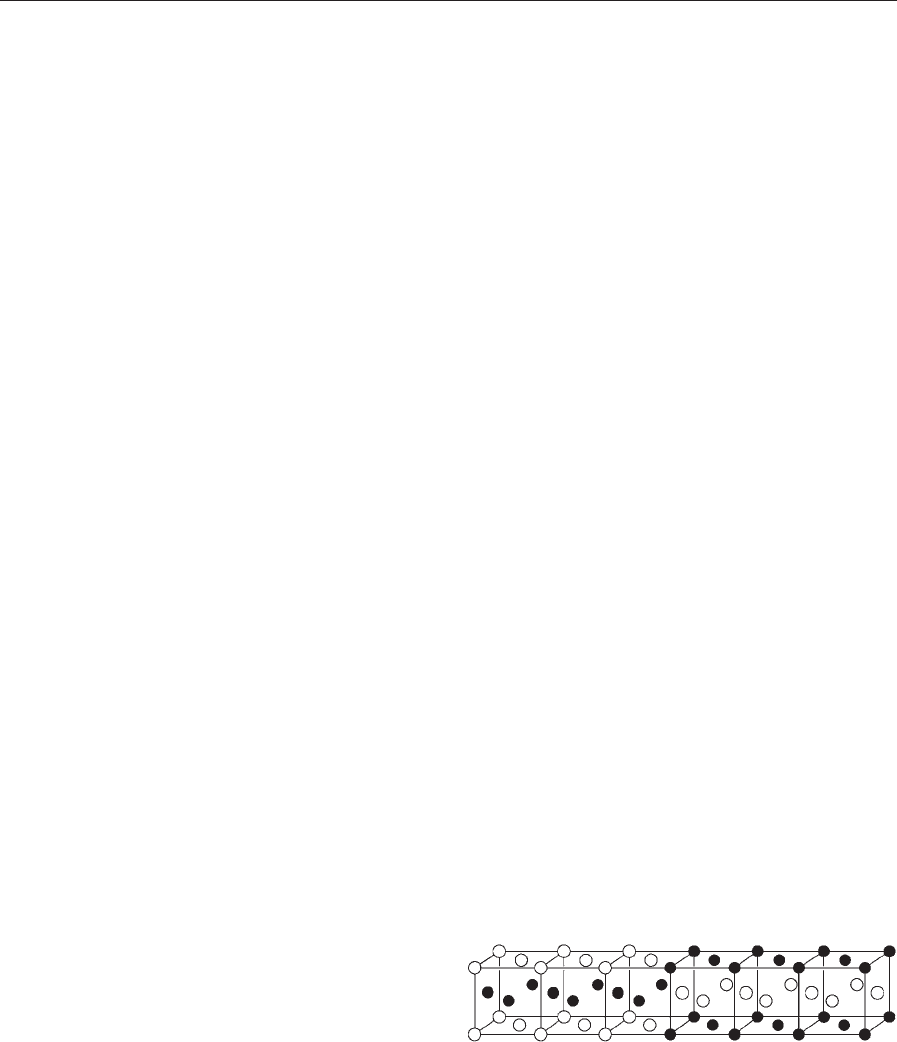

the left-hand (or right-hand) part of Fig. 1, the unit

cell of this structure can be obtained by atomic or-

dering of the two components (filled and open cir-

cles), an atomic ordering that leads to a small

contraction of the c-axis. As discussed below, the at-

tainment of this tetragonal structure for CoPt and

FePt alloys is metallurgically different from that for

MnAl alloys. The permanent magnets based on com-

pounds of this tetragonal crystal structure are rather

expensive for CoPt and FePt owing to the high price

of platinum metal. The application of the latter mag-

nets is therefore a restricted one. The MnAl magnets

are low-cost, low-performance magnets, but their

widespread application suffers from the competition

of hard ferrite magnets (see Alnicos and Hexaferrites).

1. Permanent Magnets based on Noble Metal

Compounds

At high temperatures the platinum–cobalt phase

diagram is characterized by a range of complete

solid solubility. The crystal structure is a disordered

f.c.c. structure over the whole solid solubility range,

in which cobalt and platinum atoms statistically

occupy the crystallographic sites. This high-temper-

ature phase is practically useless for permanent

magnet applications because it does not show a suf-

ficiently high magnetic anisotropy. Structural trans-

formations take place, however, when the rapidly

cooled solid solution Co

1x

Pt

x

alloys are annealed at

lower temperatures. The f.c.c. phase gives rise to a

disorder–order transformation for comparatively

high platinum concentrations (x40.75) whereas for

Figure 1

Schematic representation of an array of unit cells of the

tetragonal AuCu structure type in which one component

occupies the basal plane positions and the other

component the equatorial plane positions. Switching of

positions can lead to an antiphase boundary visible in

the central part.

478

Magnetic Materials: Hard

relatively low platinum concentrations (xo0.23) it

transforms into a h.c.p. structure. The applicability of

Co

1x

Pt

x

alloys as permanent magnet materials is

based on the transformation of the disordered f.c.c.

phase to an ordered face-centered tetragonal (f.c.t.)

phase occurring for alloys in the intermediate con-

centration range (40oxo75). Only the latter phase

has a sufficiently high uniaxial magnetic anisotropy,

the easy magnetization direction being along the

tetragonal c-axis.

The origin of the magnetic anisotropy and the role

played by the orbital moment in transition metal

compounds in CoPt has been explained by means of

first principles band structure calculations using the

local spin density approximation. For a more detailed

discussion of this topic the reader is referred to the

review by Buschow (1997). The Curie temperature of

these materials is around 500 1C for the equiatomic

composition and slightly decreases with platinum

concentration.

The maximum of the magnetic anisotropy energy

E

A

¼K

1

þ2K

2

is found at the equiatomic composi-

tion, although the maximum of the anisotropy field

H

A

¼(2K

1

þ4K

2

)/M

s

is located at slightly higher x

values because of the fairly strong decrease of the

saturation magnetization, M

s

, with x. For obtaining

optimum values for the coercivity slightly higher

platinum concentrations than the equiatomic com-

position are desirable because it is the anisotropy field

rather than the anisotropy energy that determines the

coercivity (see Coercivity Mechanisms). However, the

energy product depends very strongly on the mag-

netization. For this reason, concentrations close to

the equiatomic composition are generally chosen for

practical applications in permanent magnets.

As described in detail elsewhere (see Coercivity

Mechanisms) high coercivities are usually obtained in

magnet bodies composed of an assembly of suffi-

ciently fine particles. CoPt alloys are known to have

outstanding mechanical strength and for this reason

the powder metallurgical route commonly used for

the attainment of high coercivities in many other

permanent magnet materials (see Magnets: Sintered )

is not applicable here. In these alloys one may profit,

however, from particulars of the phase diagram be-

cause the presence of the f.c.c.-to-f.c.t. phase transi-

tion provides ample means of obtaining sufficiently

small f.c.t. particles. This is the reason that the gen-

eration of coercivity in CoPt alloys is a matter of

controlling the nucleation and growth of f.c.t. parti-

cles during the phase transformation. This process

involves heat treatments of the ingots under carefully

selected conditions.

Kaneko et al. (1968) have shown that the coercivity

passes through a maximum when CoPt alloys are

heat treated for variable aging times at temperatures

sufficiently below the f.c.c.–f.c.t. transformation tem-

perature, the optimum annealing temperature being

around 680 1C. Furthermore, it has been found that

even better results are obtained when the first aging

step is followed by a second aging step, provided the

first aging step is kept sufficiently short to prevent

overaging. The first annealing step is regarded as

leading to the formation of a fine precipitate of the

f.c.t. phase in the f.c.c. matrix, whereas the second

step is held responsible for an increase of the mag-

netocrystalline anisotropy of the f.c.t. phase. This in-

crease is probably associated with a more perfect

atomic ordering of the cobalt and platinum atoms in

the f.c.t. grains. By applying this two-step annealing

process, coercivities can be obtained of greater than

700 kAm

1

for alloys annealed first at 680 1C and

subsequently at 600 1C for variable times. The corres-

ponding energy products of the ingot magnets can

reach values around 100 kJm

3

.

The origin of the coercivity in f.c.t. CoPt alloys has

been studied (Zhang and Soffa 1994) by means of

Lorentz microscopy. It has been shown that the oc-

currence of antiphase boundaries (APB) is essential

for the understanding of the coercivity in these ma-

terials. It is mentioned above that the f.c.t. phase

precipitates from a disordered f.c.c. matrix phase on

annealing. This phase transformation proceeds by

means of a nucleation and growth mechanism, start-

ing at a multitude of different locations in the alloy.

The coalescence of the ordered regions during the

growth process invariably leads to the occurrence of a

large number of APBs. The atomic arrangement at

APBs is shown schematically in Fig. 1. Zhang and

Soffa (1994) showed by means of electron microscopy

that the microstructure of fully ordered alloys can be

characterized by profuse micro- and macrotwinning,

leading to a dense net of APBs within the micro- and

macrotwins. It is assumed that the coercivity is con-

trolled by domain wall pinning at APBs and stacking

faults.

Behavior fairly similar to that described above for

Co

1x

Pt

x

alloys is found also for Fe

1x

Pt

x

alloys.

High coercivities for Fe

1x

Pt

x

alloys are obtained

when alloys around the equiatomic composition are

first homogenized at high temperatures and subse-

quently annealed at temperatures below the order–

disorder transition temperature. Tanaka et al. (1997)

made a fairly detailed investigation of the microstruc-

tures of heat-treated Fe

1x

Pt

x

alloys and the resulting

coercivities. It was shown that composition control is

essential for the attainment of high coercivities. In as-

quenched alloys optimum coercivities are reached for

39.5 at.% platinum because the disordered f.c.c. phase

disappears during quenching and can no longer act as

nucleation centers for domain walls. Tanaka et al.

(1997) further showed that alloys with optimum co-

ercivities are reached after heat treatments in which

the local stress associated with the cubic-to-tetragonal

transformation is not yet released by twin formation,

and the f.c.t. phase is still present in the form of

nanoscale antiphase domains. The antiphase domain

boundaries between the single-domain particles act as

479

Magnetic Materials: Hard