Buschow K.H.J. (Ed.) Concise Encyclopedia of Magnetic and Superconducting Materials

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

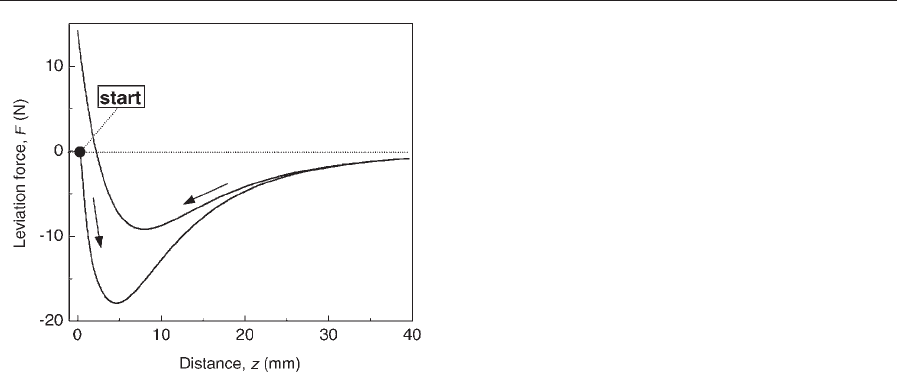

repulsive force develops. In Fig. 2, the vertical force

between a YBCO disk (diameter 25 mm) and an

Sm–Co permanent magnet (diameter 25 mm) is plot-

ted against the vertical distance. The repulsive force

increases as the magnet approaches the superconduc-

tor and reaches a maximum value for a small distance.

The force at a given distance becomes smaller when

the magnet is moved away from the superconductor.

This hysteretic behavior can be explained by the pen-

etration of magnetic flux into the superconductor. A

small attractive force component develops due to flux

pinning and reduces the repulsive force for increasing

distance between superconductor and magnet.

The case of zero-field cooling is impractical for

superconducting bearings in which superconductors

and permanent magnets are assembled at 300 K. In

this case, the superconductors are cooled to below T

c

in the presence of the magnetic field of the permanent

magnets (field cooling). In type II superconductors

discrete structures in the material, so-called flux lines,

create paths for the magnetic flux. The motion of flux

lines is prevented by their interaction with defects in

the superconductor. Therefore, the field distribution

of the permanent magnets is frozen within the super-

conductor. The pinning-assisted levitation after field

cooling is generally more stable against displacements

in the horizontal direction than the levitation after

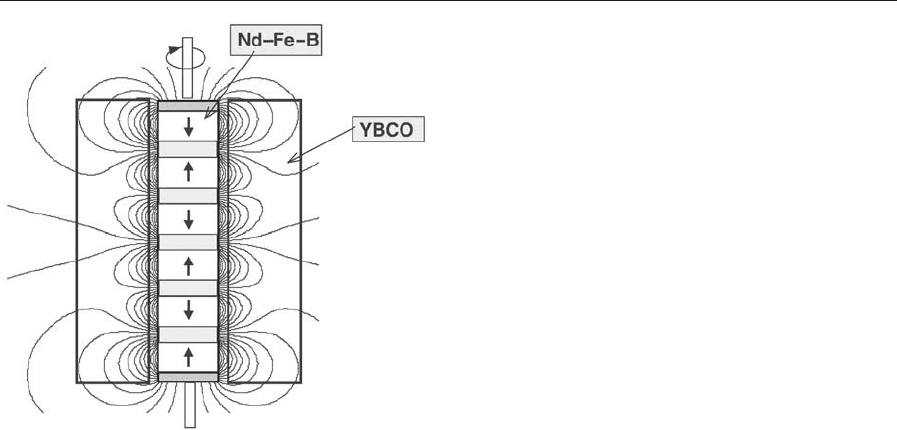

zero-field cooling. An example for the vertical force

versus distance relation after field cooling is shown in

Fig. 3. The force which is almost zero after field

cooling becomes negative as the permanent magnet is

moved away from the superconductor. This attractive

force can be used for stable levitation via suspension,

i.e., with the permanent magnet below the supercon-

ductor.

4. Upper Limi t for the Bearing Pressure

The levitation force of a superconducting bearing is

enhanced with increasing magnetization of the su-

perconductor, the latter being proportional to the

critical current density j

c

and the diameter of a single-

domain YBCO sample (see Sect. 2). The strong in-

crease of the critical current density with decreasing

temperature can be used to reach higher levitation

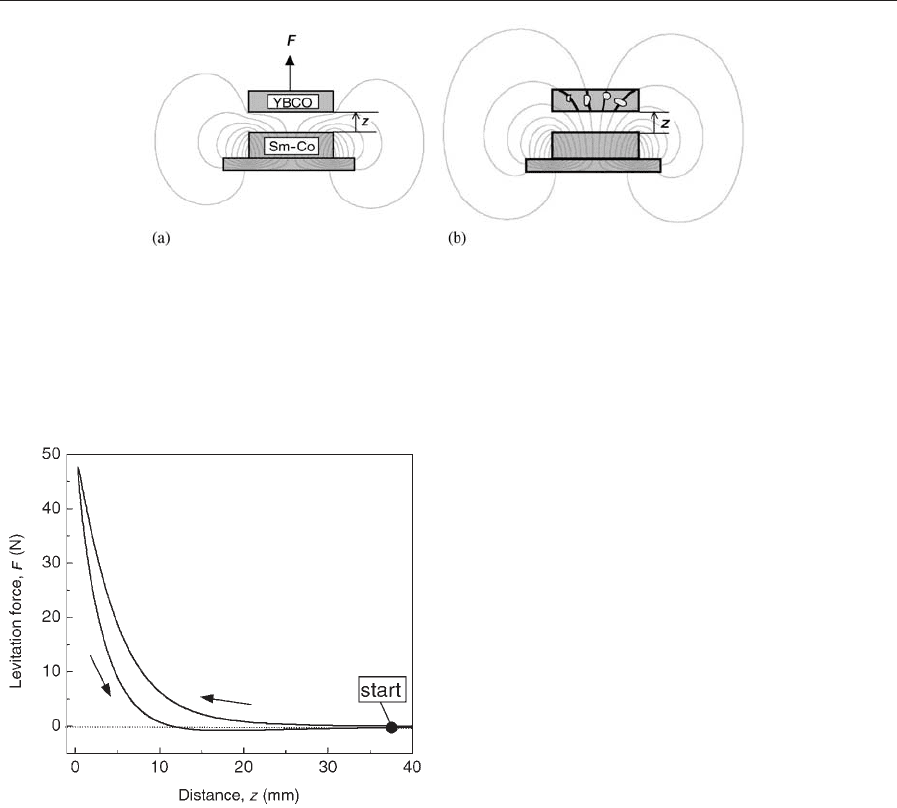

Figure 1

Superconducting magnetic bearing consisting of a YBCO disk and a permanent magnet. The iron plate below the

permanent magnet is used to focus the magnetic flux on the superconductor. (a) Cooling of the YBCO disk in a large

distance from the permanent magnet (zero-field cooling). If the distance is reduced, a repulsive force develops due to

the diamagnetism of the superconductor. No magnetic flux penetrates the superconductor as shown by the magnetic

field lines. (b) Cooling of the YBCO disk in a small distance from the permanent magnet (field cooling). The levitation

force is based on the pinning of flux lines, i.e., by their interaction with defects within the superconductor.

Figure 2

Vertical levitation force between a YBCO disk (diameter

25 mm) and an Sm–Co permanent magnet (diameter

25 mm) in dependence on the distance between

superconductor and permanent magnet after zero-field

cooling. The force is mainly repulsive. A very small

attractive levitation force is observed only for increasing

distance.

460

Magnetic Lev itation: Superconduc ting Bearings

forces than at 77 K. However, the magnetization of

the superconductor cannot exceed the magnetization

value that is necessary to produce a diamagnetic

image of the permanent magnet for zero-field cooling.

The upper limit of the levitation force achievable for

a given permanent magnet would be obtained for an

ideal superconductor of infinite site and infinitely

large critical current density that would perfectly

shield the magnetic field of the permanent magnet.

The resulting levitation force is equivalent to the in-

teraction between the permanent magnet and its mir-

ror magnet at zero gap and is given by (Teshima et al.

1996)

F

max

¼ AB

2

s

=ð2m

0

Þð1Þ

where A is the magnet pole face and B

s

is the surface

field on the magnet face. By dividing this force by A

one obtains the bearing pressure

F

max

=A ¼ B

2

s

=ð2m

0

Þð2Þ

For a maximum field strength of B

s

¼0.5 T, which

is typical for good rare earth magnets, the maximum

achievable bearing pressure is F

max

/A ¼B

s

2

/(2m

0

)

E31 N cm

2

. The experimental values for YBCO sam-

ples mentioned above achieve up to 70% of this

upper limit. Much larger bearing pressures up to

5000 N cm

2

are expected if a superconducting per-

manent magnet with a trapped fields as high as 11 T

would be used instead of a conventional permanent

magnet. Such high trapped fields are available in bulk

YBCO at temperatures B30 K (Gruss et al. 2001,

Gonzales-Arrabal et al. 2002). The most important

problem which has to be solved in order to utilize

YBCO magnets for applications at temperatures low-

er than 77 K is to magnetize the superconductor.

Pulsed magnetic fields can be used for magnetizing

YBCO disks. However, large viscous forces act on the

penetrating magnetic flux, especially in the case of

short rise times (B1 ms) of the pulsed field. The heat

generated by the rapid motion of magnetic flux

strongly reduces the trapped field achievable at tem-

peratures lower than 77 K. One possibility to over-

come this problem is to increase the rise time of the

pulsed field.

5. Rotating HTS Bearings

Simply designed thrust bearings (see Fig. 1) have an

axial geometry, i.e., the bulk YBCO is assembled as a

plane stator sandwiched by a permanent ring magnet

which is connected to the rotor. However, the axial-

type superconducting bearing has limitations with

regard to the vertical levitation force F

z

and magnetic

stiffness. The stiffness is defined as the change of the

force for a small displacement of the permanent

magnet from its initial position. In order to improve

the stiffness one can replace the permanent magnet in

Fig. 1 by a set of concentric permanent ring magnets.

Nevertheless, especially the horizontal stiffness dF

x

/

dx (for a displacement of the permanent magnet par-

allel to the superconductor) remains relatively small.

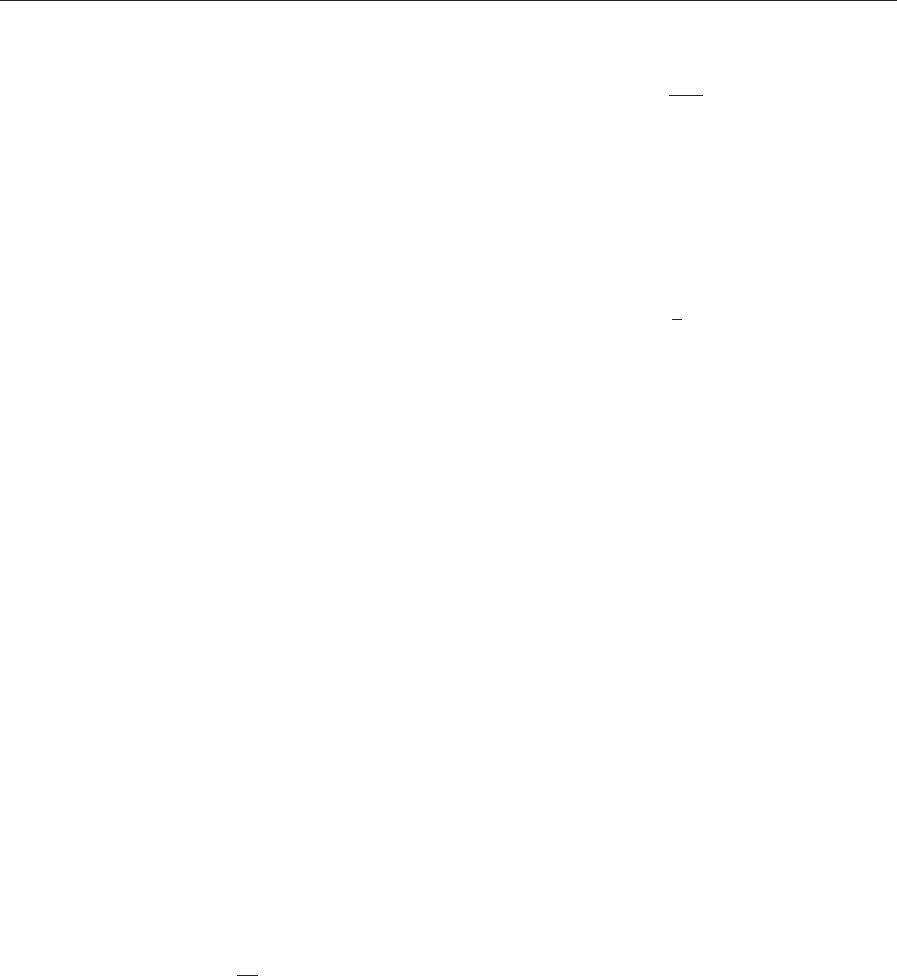

In order to overcome these limitations, journal-type

bearings have been developed (Kummeth et al. 2002,

Schultz et al. 2002) in which a special arrangement of

permanent magnets and iron disks leads to high

magnetic gradients both in axial and radial direction.

The bearing shown schematically in Fig. 4 consists of

a YBCO hollow cylinder and stacks of permanent

magnets and iron disks. Neighboring magnets in

the YBCO hollow cylinder of the radial bearing are

polarized in the opposite direction and separated by

iron disks. In this way, the magnetic flux is focused

on the gap between the magnets and guided in radial

direction, generating a highly inhomogeneous field

distribution within the superconductor. The large

magnetic gradients obtained with such configurations

result in high values of both radial and axial stiffness

provided that the interface between the superconduc-

tor and the stack of magnets and iron disks is large

enough. A radial stiffness of 160 N mm

1

was re-

ported for such a bearing in which the YBCO hollow

cylinder was 9 cm long and had an inner diameter of

4 cm (Schultz et al. 2002). The radial stiffness can be

easily scaled up by increasing the radial dimension of

the superconducting bearing. It is noteworthy that,

independent of the bearing type, the horizontal stiff-

ness dF

x

=dx after field-cooling is exactly half the

vertical stiffness dF

z

/dz.

Figure 3

Vertical levitation force between a YBCO disk (diameter

25 mm) and an Sm–Co permanent magnet (diameter

25 mm) in dependence on the distance between

superconductor and permanent magnet after field

cooling. The levitation force is mainly attractive.

461

Magnetic Levitation: Superconducting Bearings

6. Applications of HTS Bearings

Promising applications of rotating HTS bearings are

cryogenic turbopumps, because in this case the cry-

ogenic environment already exists. HTS bearings

could replace the mechanical bearings of turbopumps

which have very poor tribological properties at cry-

ogenic temperatures. Of special interest are turbo-

pumps (with HTS bearings) for liquid hydrogen

which is considered as the fuel of the future. Another

applications for which a cryogenic environment exists

are superconducting reluctance motors in which large

bulk YBCO pellets are used in the rotor in order

to increase the energy density up to a factor of 2

(Oswald et al. 2003). High-speed centrifuges are an-

other attractive application of HTS bearings. Proto-

type centrifuges designed with HTS bearings were

successfully tested up to 30 000 rpm (Werfel et al.

2001). HTS bearings have a great potential to im-

prove the performance of flywheels for energy

storage. With HTS bearings the high-speed idling

losses of flywheels can be drastically reduced to val-

ues of 0.1% per hour compared to 1% per hour for

flywheels with conventional bearings. This would

allow to construct flywheels with a 90% diurnal stor-

age efficiency. In flywheels prototypes with HTS

bearings, energies in the range of more than 1 kWh

have already been stored (Nagaya et al. 2001).

Promising applications of linear HTS bearings are

noncontact transport systems in clean-room environ-

ments of microelectronic factories, where the con-

tactless motion would not create any wear debris, in

track-bound individual traffic systems, or in elevators

(Schultz et al. 2002).

7. Summary

The most promising application of bulk HTS is the

development of HTS bearings utilizing the inherently

stable levitation between the bulk HTS and perma-

nent magnets. The main parameters of HTS bearings

as the levitation forces and magnetic stiffness depend

on the properties of superconductor and permanent

magnet. Large melt-textured YBCO with high critical

current densities are now available. As a result of the

large progress in this field, the bearing pressure of

modern HTS bearings, i.e., the levitation force divid-

ed by the area of the permanent magnet, is mainly

limited by the surface field of the permanent magnet.

HTS bearings operating at 77 K can be used in order

to realize frictionless support in rotating machines (as

flywheels for energy storage, superconducting mo-

tors, cryogenic pumps, high-speed centrifuges), and

for frictionless linear transportation. The latter

should allow transportation of extremely heavy ob-

jects which can no longer be moved by wheel systems,

like concrete ports or moving bridges. Moreover,

contactless transportation which does not create any

wear debris can advantageously be used in clean

rooms in the microelectronics industry.

See also: Magnetic Levitation: Materials and Proc-

esses; Superconducting Machines: Energy Storage;

Superconducting Permanent Magnets: Potential Ap-

plications; Superconducting Permanent Magnets:

Principles and Results

Bibliography

Braunbeck W 1939 Freies Schweben diamagnetischer Ko

¨

rper

im Magnetfeld. Z. Physik. 112, 764–79

Buchhold T A 1960 Applications of superconductivity. Sci. Am.

202 (3), 74

Earnshaw S 1842 On the nature of molecular forces which reg-

ulate the constitution of luminiferous ether. Trans. Cam-

bridge Phil. Soc. 7, 97–112

Gonzales-Arrabal R, Eisterer M, Weber H W, Fuchs G, Verges

P, Krabbes G 2002 Very high trapped fields in neutron ir-

radiated and reinforced YBa

2

Cu

3

O

7d

melt-textured super-

conductors. Appl. Phys. Lett. 81, 868–70

Gruss S, Fuchs G, Krabbes G, Verges P, Sto

¨

ver G, Mu

¨

ller K H,

Fink J, Schultz L 2001 Superconducting bulk magnets: very

high trapped fields and cracking. Appl. Phys. Lett. 79, 3131–3

Hull J R 2000 Superconducting bearings. Supercond. Sci. Tech-

nol. 13, R1–15

Figure 4

Schematic view of a superconducting magnetic bearing

consisting of a YBCO hollow cylinder and a stack of

Nd–Fe–B permanent magnets and iron disks (for details

see text). The field distribution in the superconducting

hollow cylinder after field cooling is shown. For the

application in a rotating machine the YBCO hollow

cylinder is held stationary, whereas the inner part with

the magnets and iron disks is connected with the rotor of

the machine.

462

Magnetic Lev itation: Superconduc ting Bearings

Krabbes G, Scha

¨

tzle P, Bieger W, Fuchs G, Wiesner U, Sto

¨

ver

G 1997 Thermodynamically controlled melt processing to

improve bulk materials. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 7,

1735–8

Kummeth P, Nick W, Ries G, Neumu

¨

ller H W 2002 Develop-

ment of superconducting magnetic bearings. Physica C

372–376, 1470–3

Moon F C 1994 Superonducting Levitation. Wiley, New York

Murakami M 1992 Processing of bulk YBaCuO. Supercond.

Sci. Technol. 5, 185–203

Nagaya S, Kashima N, Minami M, Kawashima H, Unisuga S,

Kakiuchi Y, Ishigaki H 2001 Study on characteristics of high

temperature superconducting magnetic trust bearing for

25 kWh flywheel. Physica C 357–360, 866–9

Oswald B, Krone M, Strasser T, Best K J, Soell M, Gawalek W,

Gutt H J, Kovalev L, Fisher L, Fuchs G, Krabbes G, Frey-

hardt H C 2003 Design of HTS reluctance motors up to

several hundred kW. Physica C 372–376, 1513–6

Schultz L, Krabbes G, Fuchs G, Pfeiffer W, Mu

¨

ller K H 2002

Superconducting permanent magnets and their application in

magnetic levitation. Z. Metallkd. 93, 1057–64

Teshima H, Morita M, Hashimoto M 1996 Comparison of the

levitation forces of melt-proessed YBaCuO superconductors

for different magnets. Physica C 269, 15–21

Werfel F N, Flo

¨

gel-Delor U, Rothfeld R, Wippich D, Riedel T

2001 Centrifuge advances using HTS magnetic bearings.

Physica C 354, 13–7

G. Fuchs

IFW, Dresden, Germany

Magnetic Losses

The term magnetic losses generically refers to the

various energy dissipation mechanisms taking place

when a magnetic material is subject to a time-varying

external field H(t). As a consequence of the inherent

irreversible nature of magnetization processes, part of

the energy injected into the system by the external

field is irrevocably transformed into heat. A case of

particular interest is the one where the material is

subject to a cyclic field of frequency f, with the field

and the average magnetic induction B in the material

remaining colinear during the process.

Then the time integral

W ¼

Z

H

dB

dt

dt ð1Þ

over one magnetization cycle gives the energy per unit

volume transformed into heat in the cycle. This in-

tegral is usually termed loss per cycle, whereas the

term power loss is used to denote the loss per unit

time P ¼fW.

Simple expressions can be derived for W when the

equilibrium relationship between field and induction

in the material is linear, B ¼mH, and the delayed re-

sponse to time variations of the field is characterized

by the single time constant t. Then, the loss per cycle

under sinusoidal field can be expressed as

W ¼

2p

2

t

m

B

2

f ð2Þ

where B represents the induction peak value in the

cycle. Under these conditions: (i) hysteresis loops are

elliptical—that is, the system response to the sinusoi-

dal field is sinusoidal; and (ii) the loss per cycle is

proportional to the frequency.

When the system is still linear but the dynamic

response is controlled by multiple time constants,

Eqn. (2) takes the more general form

W ¼

p

m

B

2

tgf ð3Þ

where the parameter f, the so-called loss angle,

measures the lag of the induction with respect to the

field. The loss behavior is governed by the depend-

ence of f on frequency. In general, f-0 when f-0,

i.e., the loss vanishes under quasi-static excitation,

where the material response must reduce to the dis-

sipationless linear law B ¼mH. In the particular case

of Eqn. (2), tgf ¼2pft.

Magnetic materials are inherently nonlinear hyst-

eretic systems where strong deviations from the be-

havior described by Eqns. (2) and (3) are observed.

The loss per cycle is a nonlinear function of frequency

and the response to a sinusoidal excitation is usually

heavily distorted. In addition, the loss depends not

only on the magnetization frequency f and the peak

induction B, but also on the induction wave-shape,

which means that losses under sinusoidal induction

are in general different from losses under triangular

induction at the same peak induction and frequency.

International standards require that magnetic losses

be measured under controlled sinusoidal induction

rate and give detailed prescriptions about admitted

methods and tolerances in the realization of the

appropriate test conditions.

Various mechanisms are active during the magnet-

ization process and can contribute to magnetic losses.

Examples are the generation and decay of spin waves

or acoustic waves, and, in metals, the decay by the

Joule effect of the electric currents (eddy currents)

induced by the induction changes in the material.

These mechanisms are all activated by the motion of

the domain walls separating different magnetic do-

mains or by the large-scale instabilities accompanying

the nucleation and annihilation of magnetic domains

(see also Magnets, Soft and Hard: Domains). The

chief problem in the study and application of mag-

netic materials is the prediction of the complex loss

behavior observed in experiments in terms of these

mechanisms.

Eddy current effects are dominant in metallic soft

magnetic materials, where the principal magnetiza-

tion process is just the eddy-current-damped motion

463

Magnetic Losses

of magnetic domain walls. The loss figure is the fun-

damental quality parameter used to monitor material

production and to select the materials best suited to

particular applications. In the following sections, at-

tention will be mainly focused on magnetic losses in

metallic materials. Other loss aspects not discussed in

this article arise in relation to magnetic after-effects

(see Magnetic Viscosity) and resonance phenomena

(see Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Spectrometry).

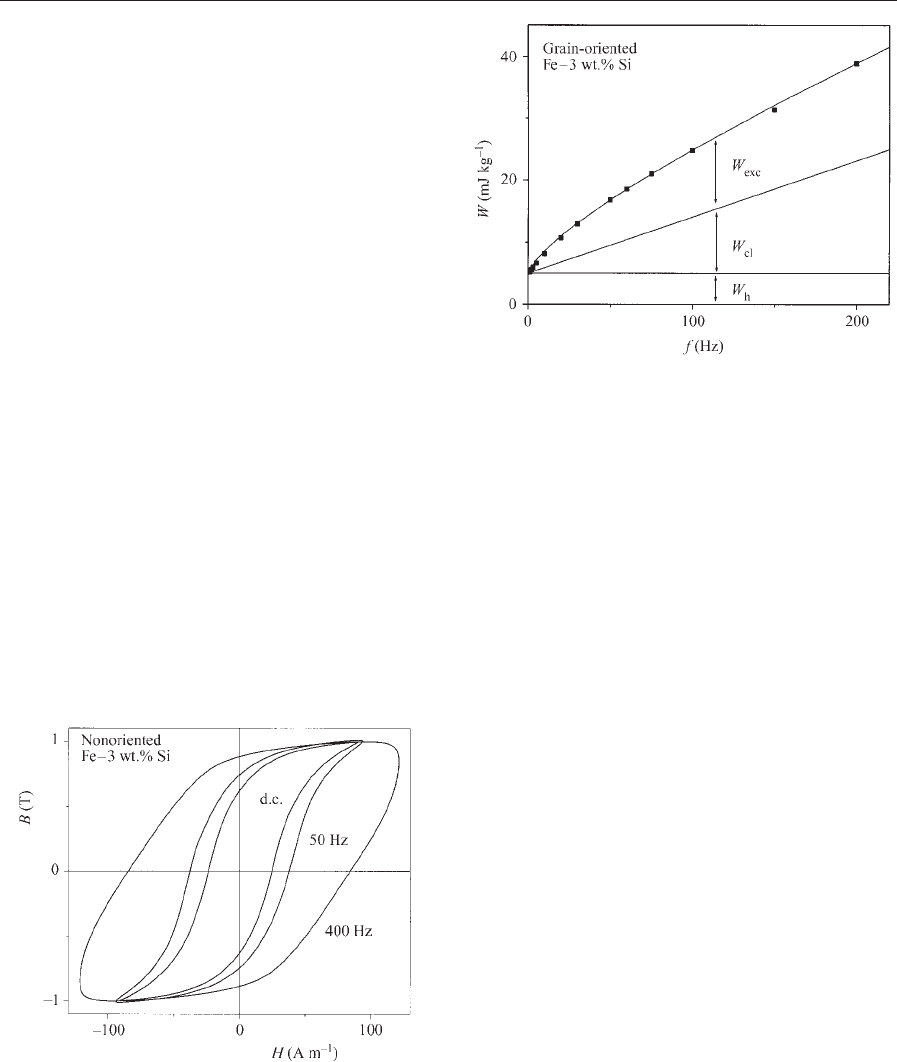

1. Loss Separation

The typical behavior of dynamic hysteresis loops and

magnetic losses in a metallic soft magnetic material is

shown in Figs. 1 and 2. The following points should

be noted:

*

the dynamic loops are far from elliptical, with

shapes strongly dependent on frequency, peak induc-

tion, and material microstructure;

*

the loop area W is a nonlinear function of f, the

nonlinearity being more pronounced at low frequency;

*

the loop area W tends toward a nonzero limit

when the magnetization frequency is reduced toward

zero: this value is referred to as (quasi)-static loss or

hysteresis loss;

*

the loss significantly increases above the quasi-

static limit already at frequencies of a few Hz.

The physical picture underlying this complex be-

havior is clear in principle (Cullity 1972). A change of

induction always accompanies the motion of a do-

main wall. Because of Faraday’s law, this change

gives rise to a rotational electric field E around the

moving wall and consequently to an electric current

density j ¼sE (eddy current), where s is the electrical

conductivity of the material. Therefore, in any

elementary volume Dv of the material, the power

(7j7

2

/s)Dv is dissipated through the Joule effect. The

total loss is obtained by summing up these contribu-

tions over all elementary volumes. The result will

depend on the space–time details of the eddy-current

density j(r,t). This function will be as complicated as

typical magnetic domain structures are, and a

straightforward calculation of the loss by direct in-

tegration is impossible in the majority of cases.

Given the complexity of the problem, in practice

one looks for phenomenological laws summarizing in

simple terms the regularities observed in experiments.

Most useful in this respect is the concept of loss sep-

aration, according to which the total power loss P at

frequency f is decomposed into the sum of three con-

tributions, P

h

, P

cl

, and P

exc

, termed hysteresis loss,

classical loss , and excess loss, respectively (see Fig. 2),

such that

P ¼ P

h

þ P

cl

þ P

exc

ð4Þ

This deconvolution reflects the existence of three

scales in the magnetization process: the scale set by

the specimen geometry (classical loss), the scale of

domain wall-pinning mechanisms (hysteresis loss),

and the scale of magnetic domains (excess loss).

Given the complex, strongly nonlinear character of

the magnetization process, there is no obvious reason

why the superposition law expressed by Eqn. (4)

should hold true under broad conditions. In fact, it is

Figure 1

Typical dynamic hysteresis loops for a nonoriented Fe–

3 wt.% Si lamination 0.35 mm thick, measured under

controlled sinusoidal induction rate at a peak induction

of 1 T and at different frequencies (quasi-static (d.c.),

50 Hz, 400 Hz).

Figure 2

Loss per cycle and per unit mass as a function of

frequency for a grain-oriented Fe–3 wt.% Si lamination

0.30 mm thick. The hysteresis (W

h

), classical (W

cl

), and

excess (W

exc

) loss components involved in loss

separation are indicated (courtesy of Luciano

Rocchino).

464

Magnetic Los ses

only by applying statistical methods to the analysis of

stochastic magnetization processes that one is able to

show that the three scales just mentioned affect the

loss in an approximately statistically independent

way (Bertotti 1998).

1.1 Classical Loss

The classical loss is the loss calculated from Maxwell

equations for a perfectly homogeneous conducting

medium, that is, with no structural inhomogeneities

and no magnetic domains (Bozorth 1993). The scale

relevant to the classical loss is the scale set by the sys-

tem geometry—for example, in a lamination, the slab

thickness d. This scale controls the boundary condi-

tions for Maxwell equations, which in turn determine

the distribution of eddy currents in the specimen cross-

section and the ensuing Joule dissipation. The classical

loss acts as a sort of background loss, present under all

circumstances, to which other contributions are added

when structural disorder and magnetic domains play a

role. By solving Maxwell equations, one finds that the

classical loss takes the form

P

cl

¼

p

2

sd

2

6

ðBf Þ

2

ðWm

3

Þð5Þ

when it is calculated for a lamination of thickness d

and electrical conductivity s, magnetized at the fre-

quency f and at the peak induction B. As mentioned

before, the loss does depend on the induction wave-

form even when f and B are fixed. Equation (5) is valid

under sinusoidal induction. The minimum loss is at-

tained under triangular induction (i.e., constant dB/dt

in each magnetization half-cycle). In that case, the co-

efficient p

2

/6 is reduced to 4/3.

Equation (5) contains no parameter describing the

magnetization law of the material. All materials be-

have in the same way if their geometry and their

electric properties are the same. This remarkable

simplification derives from the fact that Eqn. (5) is

actually a low-frequency limit, valid only when the

induction rate dB/dt is approximately uniform

throughout the lamination thickness. With increas-

ing frequency, this is no longer the case. The magnetic

field produced by eddy currents, being opposed to the

external field, tends to inhibit magnetization reversal

in the interior of the lamination. This eddy-current

shielding effect yields deviations from Eqn. (5) that

depend on the magnetization law of the material

(Mayergoyz 1998). In the case of a linear magneti-

zation law, B ¼mH and in the limit of heavy shield-

ing, i.e., smd

2

fb1, instead of Eqn. (5) one obtains

P

cl

¼

p

3=2

2

ffiffiffiffiffiffiffiffi

sd

2

m

s

B

2

f

3=2

ðWm

3

Þð6Þ

In a silicon steel lamination with sD210

6

O

1

m

1

,

m/m

0

D2 10

3

(m

0

¼4p 10

7

TmA

1

is the

permeability of the vacuum), and dD3 10

4

m, one

finds that smd

2

fD1 at frequencies fD2kHz. Con-

versely, whenever field amplitudes much larger than

the material coercive field are involved, it may be ap-

propriate to approximate the magnetization law of the

material by a step function, jumping between opposite

values of maximum induction when the field changes

sign. Under these conditions, the loss takes the value

P

cl

¼

p

2

sd

2

4

ðBf Þ

2

ðWm

3

Þð7Þ

This expression is simply 3/2 times the low-frequency

limit of Eqn. (5).

1.2 Hysteresis Loss

Hysteresis losses are the consequence of the fact that

on the microscopic scale the magnetization process

proceeds through sudden jumps of the magnetic do-

main walls that are unpinned from defects or other

obstacles by the pressure of the external field (see also

Magnetic Hysteresis). The local eddy currents in-

duced by the induction change accompanying the

wall jump dissipate a finite amount of energy through

the Joule effect.

The sum over all jumps gives the hysteresis loss

associated with the jump sequence. The jumps are so

short (of the order of 10

8

–10

9

s) that the external

field is unable to influence the internal jump dynam-

ics. The only effect of the field is to compress or ex-

pand the time interval between subsequent jumps in

inverse proportion to the field rate of change, which

yields a number of jumps per unit time and an

amount of energy dissipated per unit time propor-

tional to the magnetization frequency. Therefore, for

the hysteresis loss in a loop of peak induction B, one

obtains the typical expression

P

h

¼ 4k

hyst

B

a

f ð8Þ

The loss per cycle W

h

¼P

h

/f is thus independent of

frequency (see Fig. 2). The parameter k

hyst

and the

exponent a include the structural aspects affecting

domain wall pinning and magnetization reversal.

Their value will differ from material to material. The

rule a ¼1.6 has been claimed to have some general

validity and is known in the literature as Steinmetz

law (Bozorth 1993).

The hysteresis loss is intimately related to the

structural disorder in the material. Possible sources of

domain wall pinning are interstitials, nonmagnetic or

less-magnetic inclusions, voids, or dislocations. At a

higher level of complexity, dislocation tangles and

grain boundaries play a role. In amorphous alloys,

fluctuations of local exchange and anisotropy should

be taken into account, but often, in all cases where

magnetostriction is not negligible, magnetoelastic

coupling to randomly distributed internal stresses

465

Magnetic Losses

dominates. Finally, in thin ribbons, surface rough-

ness may be a substantial source of pinning effects.

1.3 Excess Loss

Excess losses arise from the existence of a third rel-

evant scale in the magnetization process, the scale of

magnetic domains. The excess loss results from the

smooth, large-scale motion of domain walls across

the specimen cross-section, when the fine-scale jumps

responsible for the hysteresis loss are disregarded.

Eddy currents tend to concentrate around the moving

domain walls, a fact that gives rise to losses higher

than the classical ones because of the quadratic de-

pendence of the local loss (7j7

2

/s)Dv on the intensity

of the eddy-current density (Williams et al . 1950, Pry

and Bean 1958).

According to the picture just described, excess

losses are expected to be as ubiquitous as the presence

of magnetic domains. However, the importance of

excess losses in comparison with classical and hys-

teresis losses will substantially depend on the size and

arrangement of magnetic domains. As a general rule,

the finer the domain structure, the smaller the excess

loss contribution. This conclusion can be given a

precise quantitative measure in the case of a lamina-

tion of thickness d containing longitudinal bar-like

magnetic domains of random width (Bishop 1976). In

this case, Maxwell equations can be exactly solved,

giving the result

P

exc

¼

48

p

3

X

odd n

1

n

3

!

2L

d

P

cl

D1:63

2L

d

P

cl

ð9Þ

where 2L represents the average domain width and

P

cl

is given by Eqn. (5). Equation (9) identifies the

ratio 2L/d as the relevant parameter of the problem.

The excess loss is proportional to 2L/d and becomes

negligible with respect to the classical loss when the

domain width is much smaller than the lamination

thickness.

This prediction is helpful in the interpretation of

losses in grain-oriented silicon steels, where domain

structures are often not far from the one assumed in

the model. However, one should not forget that the

regular arrangement of longitudinal domains as-

sumed in the model can be far from the conditions

encountered in ordinary materials. In many cases, the

domain size is no longer itself the important para-

meter, because microstructural features introduce

additional characteristic lengths (e.g., grain size, fluc-

tuation wavelength of residual stresses, etc.) that tend

to control the loss problem.

In these more complex cases, the excess loss ap-

proximately follows a law of the type (Bertotti 1998)

P

exc

¼ k

exc

ffiffiffi

s

p

ðBf Þ

3=2

½Wm

3

ð10Þ

where the parameter k

exc

includes the effect of the

various relevant microstructural factors. Equation

(10) applies to grain-oriented silicon steels too, a fact

that should not be interpreted as a contradiction with

respect to Eqn. (9). The point is that the ratio 2L/d in

Eqn. (9) is unknown. In particular, there is no reason

why this ratio should be a constant of the material. In

fact, one finds that the average magnetic domain size

decreases when the magnetization frequency is in-

creased, through the nucleation of additional do-

mains. This domain multiplication process, together

with other dynamic effects—particularly domain wall

bowing (Carr 1976)—makes the dependence of losses

on frequency weaker than the quadratic one of

Eqn.(9) and eventually yields a loss law of the form of

Eqn. (10).

1.4 Factors Affecting the Total Loss

According to the previous analysis, an approximate

expression for the total power loss, valid at frequen-

cies low enough to avoid the onset of important eddy-

current shielding, is

PD 4k

hyst

B

a

f þ

p

2

sd

2

6

ðBf Þ

2

þ k

exc

ffiffiffi

s

p

ðBf Þ

3=2

ðWm

3

Þð11Þ

Classical losses depend on the combination sd

2

,

which shows that the losses are smaller the smaller

the electrical conductivity and the lamination thick-

ness. Magnetic cores of machines and devices are

never made of bulk material for this reason. On the

other hand, one of the factors that favored the in-

troduction of silicon steels was just the fact that the

addition of a few percent of silicon strongly reduces

the electrical conductivity without substantially

changing the other magnetic properties.

The hysteresis loss is independent of the electrical

conductivity s. The amount of energy dissipated in

individual wall jumps is determined by the height of

the energy barrier created by the pinning obstacle. A

change in the conductivity would alter the typical

velocity attained by the domain wall during the jump,

but not the amount of energy eventually dissipated

as heat. The hysteresis loss is also expected to be

fairly independent of the lamination thickness when

pinning effects are volume effects. The situation is

different when the surface of the lamination also acts

as a relevant pinning source. In this case, the hyster-

esis loss increases when the lamination thickness is

reduced.

Equation (11) applies to the particular case of a

material magnetized under controlled sinusoidal

induction rate. However, there are several situations

where magnetic materials operate under distorted

flux conditions, for which a generalization of

Eqn. (11) is needed. This generalization is obtained

466

Magnetic Los ses

by calculating the instantaneous power loss at indi-

vidual points of the magnetization cycle and then by

carrying out the time average over the particular

wave-shape involved. This more general expression

reads (Fiorillo and Novikov 1990)

PDP

h

þ

sd

2

12

dB

dt

2

þ k

0

exc

ffiffiffi

s

p

dB

dt

3=2

½Wm

3

ð12Þ

where the bars indicate time averaging over the mag-

netization cycle. The hysteresis loss is independent of

the induction wave-shape, provided the induction is

monotone in each magnetization half-cycle (no gen-

eration of inner hysteresis loops during the cycle).

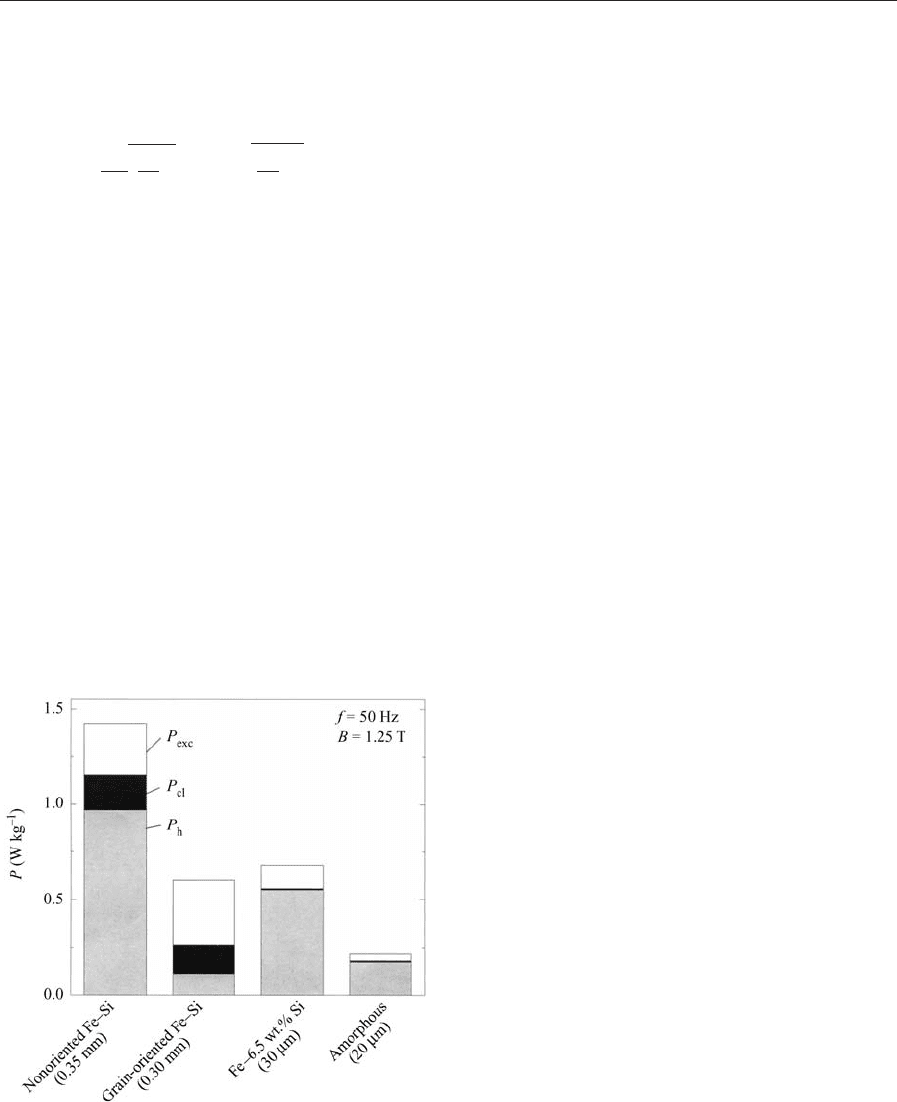

2. Loss Behavior in Different Magnetic Materials

The dependence of losses on frequency and induction

results from the combination of the three terms of

Eqn. (11). The final behavior can be rather different

from material to material, depending on the relative

contribution of the various loss components to the

total loss (Bertotti 1988) (see Fig. 3). When the ob-

jective is loss reduction, it is vital to identify the loss

term giving the dominant contribution under the

working conditions of interest and then to develop

optimization strategies for the magnetization scale

associated with that term. Metallurgical factors,

structural optimization, and control of domain struc-

tures play a role in these optimization strategies.

2.1 Iron and Low-carbon Steels

Low-carbon steels, with a typical carbon content

from 0.005 to 0.1 wt.%, are used as low-grade, low-

cost materials for magnetic cores where magnetic

losses are not the major concern and acceptable per-

formance at low price is the main goal. This is re-

flected in the fact that these materials are usually

produced as fairly thick laminations (typical thick-

ness ranges from 0.5 to 0.85 mm) which causes sub-

stantial classical losses. The presence of carbon yields

important aging effects, i.e., a progressive increase of

the hysteresis loss over time. This is due to the for-

mation of cementite precipitates, which act as addi-

tional domain wall pinning centers. Materials with

improved loss properties are obtained by purification

processes, which reduce the carbon, nitrogen, and

sulfur content, or by the introduction of some silicon

(up to 1 wt.%). When no particular purification pro-

cesses are carried out and the silicon content is

negligible, total losses take values of the order of

15 Wkg

1

at 1.5 T and 60 Hz in laminations 0.5 mm

thick. The addition of about 1 wt.% Si accompanied

by better composition control can lower the loss to

less than 8 Wkg

1

. Very clean ultra-low-carbon steels

can reach loss figures as low as 4 W kg

1

at 1.5 T and

50 Hz in 0.5 mm laminations.

2.2 Silicon Steels

Silicon steels are iron-based materials where a few

percent of soluble elements, like silicon or aluminum,

are deliberately introduced. The addition of silicon

causes a substantial increase in the electrical resistiv-

ity, with a consequent decrease in classical and excess

losses. In addition, silicon alloying yields a decrease

in the magnetocrystalline anisotropy constant, which

results in a decrease in the hysteresis loss. The main

limitation to excessive addition of silicon comes

from the progressive reduction of the saturation

magnetization and the increase in brittleness of the

material (see also Steels, Silicon Iron-based: Magnetic

Properties).

Silicon steels are divided into two main categories:

nonoriented steels and grain-oriented steels. Nonori-

ented steels are characterized by an approximate iso-

tropic grain structure. This makes them suitable for

all those applications where fairly isotropic magnetic

properties are needed. The silicon concentration

ranges from about 1 to 3.7 wt.%. Some aluminum

and manganese is also added to achieve higher elec-

trical resistivity with no detrimental effects on

the mechanical properties. The top-grade materials

have about 4 wt.% Si þAl and exhibit losses of

2.1–2.3 Wkg

1

at 1.5 T and 50 Hz in laminations

0.35–0.50 mm thick. Materials with improved losses

are developed by a careful control of impurity con-

tent, grain size, crystallographic texture, surface

state, and residual stresses. Impurities like carbon,

Figure 3

Examples of loss separation in different classes of soft

magnetic materials, at 50 Hz magnetization frequency

and 1.25 T peak induction.

467

Magnetic Losses

nitrogen, sulfur, and oxygen contribute to increasing

hysteresis losses, because they form precipitates that

act as pinning centers on moving domain walls. They

also have an indirect detrimental effect, because they

hinder grain growth and negatively affect the forma-

tion of favorable textures. Finally, the control of grain

size is important. The hysteresis loss is a decreasing

function of the average grain size s, and usually follows

a law of the type P

h

Da þb/s,wherea and b are ma-

terial-dependent constants. Conversely, the excess loss

is an increasing function of s,ofthetypeP

exc

Dks

b

,

with bB1/2. As a result, the total loss has a minimum

for a particular grain size. Material manufacturers try

to obtain materials with optimal loss performance by

appropriate grain-growth treatments. The optimal

grain size is of the order of 150 mm at 1.5 T and 50 Hz.

Contrary to nonoriented steels, grain-oriented steels

are characterized by strongly anisotropic properties.

These materials contain between 2.9 and 3.2 wt.% Si.

As the result of highly sophisticated metallurgical

processes of selective grain growth, a grain-oriented

lamination is characterized by a particular texture,

known as Goss texture, in which all the crystal grains

have one of their [001] axes close to the lamination

rolling direction. This fact, together with the large

grain size of these materials (in the millimeter–centi-

meter range) and the low impurity content yields hys-

teresis losses about one order of magnitude lower

than those typical of nonoriented steels, when the

lamination is magnetized along the rolling direction.

Grain-oriented steels are further subdivided into con-

ventional grain-oriented (CGO) and high-permea-

bility grain-oriented (HGO) materials.

The main difference is the more accurate texture

control realized in HGO materials which yields better

loss performance. In CGO steels, the lamination

thickness ranges from 0.35 to 0.23 mm and the loss

accordingly ranges from 1.4 to 1.15 Wkg

1

at 1.7 T

and 50 Hz. In HGO steels, the lamination thickness

ranges from 0.30 to 0.23 mm and the loss from 1.05 to

0.80 Wkg

1

at 1.7 T and 50 Hz. The more refined

texture control of HGO materials is reflected in the

magnetic domain structure. In fact, the nearly perfect

grain orientation yields very regular structures of

wide longitudinal bar-like domains, quite similar to

the ones assumed in the calculation of Eqn. (9). The

regularity of the domain structure and the material

perfection (very low impurity content and lack of

grain boundary effects because of the large grain size)

give a very low hysteresis loss. However, as shown by

Eqn. (9), the excess loss may attain substantial values

when wide domains are present (2L/db1).

For this reason, methods aimed at artificially re-

ducing the domain size without altering the hysteresis

loss have been developed. Two of them are of par-

ticular interest:

*

deposition of a coating on the lamination sur-

face that exerts a tensile stress of 2–10 MPa on

the material. The stress introduces a magnetoelastic

energy contribution that alters the energy balance in

the material and favors the formation of smaller

magnetic domains;

*

scribing of the lamination surface by one among

many possible techniques (mechanical scratching,

laser irradiation, plasma jet scribing, or etch pitting).

Scribing alters the magnetoelastic and magnetostatic

energy content of the lamination in a way that again

favors the formation of smaller domains.

The power loss at 1.7 T and 50 Hz is as low as

0.80 Wkg

1

in coated, scribed laminations of 0.23 mm

thickness.

2.3 Rapidly Solidified Materials

Soft magnetic materials can be prepared as very thin

ribbons by means of rapid solidification methods, in

particular by planar-flow-casting. The resulting rib-

bons have variable width (up to 20 cm and more) and

a thickness of 10–100 mm. The reduced thickness in-

hibits classical losses (see Fig. 3) and makes these

materials suited to high-frequency applications,

where classical losses play the most detrimental role.

On the other hand, rapid solidification permits the

preparation of materials in a variety of quenched

metastable states not present in the equilibrium phase

diagram, which display a broad range of interesting

magnetic and mechanical properties.

Amorphous ribbons, lacking long-range atomic

order, are prepared by rapid solidification of alloys

containing around 80 at.% transition metals and

20 at.% metalloids (B, Si, P, C). The lack of atomic

order yields electrical resistivities two to three times

larger than the corresponding crystalline alloy (typ-

ical values are in the range 120–140 10

8

Om), with

important benefits for losses. At the same time,

atomic disorder leads to a random distribution of

local magnetic anisotropy, which is averaged to zero

over the typical distances involved in magnetization

processes, a fact that yields magnetic softness and low

hysteresis loss. Magnetic softness is further enhanced

in materials with vanishing magnetostriction, because

the absence of magnetoelastic coupling eliminates the

pinning action of internal stresses. In Fe

78

B

13

Si

9

amorphous ribbons 25 mm thick, power losses attain

values around 0.25 Wkg

1

at 1.4 T and 50 Hz. Of this,

the main contribution comes from the hysteresis

component (compare Fig. 3). A similar behavior is

exhibited by nanocrystalline materials (grain dimen-

sion of the order of 10 nm) obtained by suitable an-

nealing of amorphous materials of appropriate

composition (Fe

73.5

Cu

1

Nb

3

Si

13.5

B

9

in so-called Fine-

met materials) (see also Amorphous and Nanocrystal-

line Materials).

Rapidly solidified Fe–6.5 wt.% Si materials exhibit a

favorable combination of high resistivity, low magne-

tocrystalline anisotropy, and vanishing magnetostrict-

ion, which contribute to lowering losses. Materials

468

Magnetic Los ses

with this composition cannot be prepared by rolling

techniques because of material brittleness. This draw-

back is circumvented by rapid solidification. Ribbons

with thicknesses between 30 and 100 mmcanbepre-

pared. Power losses are lower than 15 Wkg

1

at 1 T

and 1 kHz, which compares favorably with other ma-

terials for medium-frequency applications.

2.4 Nickel–Iron Alloys

Nickel–iron alloys are of particular interest because a

broad variety of qualitatively different magnetic

properties can be obtained by adjusting the compo-

sition and the preparation process. There are no re-

straints to rolling so it is possible to obtain good

laminations with thickness down to 10–20 mm, with

great benefits for classical losses. Both the crystal

anisotropy and the magnetostriction cross the zero

value for compositions around 80 wt.% Ni. Treat-

ments on materials with approximately this compo-

sition (and the deliberate introduction of other

elements like Mo, Cu, and Cr) yield materials with

extremely low hysteresis losses (coercive field less

than 1 Am

1

), and a variety of hysteresis loop shapes

controlled by induced anisotropy. The combination

of low hysteresis losses and low classical losses makes

these materials most suited to applications at high

frequencies.

2.5 Soft Ferrites for High-frequency Applications

Most applications at high frequency, up to the

100 MHz region, make use of soft ferrites, because

their nonmetallic nature precludes eddy current dis-

sipation. In most applications, mixed Mn–Zn or

Ni–Zn ferrites are employed, in which it is possible to

tailor the material properties to specific applications

by tuning the concentration of the component atoms.

The electrical resistivity is of the order of 10

7

Omin

Ni–Zn ferrites and 10

2

–10 Om in Mn–Zn ferrites.

The initial susceptibility is constant and the loss angle

(see Eqn. (3)) is negligible up to frequencies of some

MHz for Mn–Zn ferrites and 100 MHz for Ni–Zn

ferrites (see also Ferrites).

3. Conclusions

In metallic materials, magnetic losses exhibit a re-

markably complex phenomenology. Although the

physical loss mechanism is in principle clear (Joule

effect associated with the eddy currents induced by

domain wall motion), the details depend on the space–

time eddy current distribution j(r, t), which is as com-

plicated as typical magnetic domain structures are

in ordinary materials. Of central importance to the

treatment of the loss behavior is the concept of loss

separation, according to which the total loss is broken

down into the sum of three distinct contributions:

classical, hysteresis, and excess loss. Each of these

contributions is related to processes occurring in dif-

ferent spatial scales and has a distinct dependence on

magnetization frequency, peak induction, and micro-

structure. Therefore, the crucial step in any loss op-

timization strategy is to clarify which of the three loss

terms gives the dominant contribution and modify

appropriately the microstructural or geometrical con-

ditions affecting the magnetization process on that

particular scale.

See also: Amorphous Intermetallic Alloys: Resistiv-

ity; Ferrite Ceramics at Microwave Frequencies

Bibliography

Bertotti G 1988 General properties of power losses in soft

ferromagnetic materials. IEEE Trans. Magn. 24, 621–30

Bertotti G 1998 Hysteresis in Magnetism. Academic Press, Bos-

ton, MA

Bishop J E L 1976 The influence of a random domain size

distribution on the eddy-current contribution to hysteresis in

transformer steel. J. Phys. D: Appl. Phys. 9, 1367–77

Bozorth R M 1993 Ferromagnetism. IEEE Press, New York

Carr W J Jr. 1976 Magnetic domain wall bowing in a perfect

metallic crystal. J. Appl. Phys. 47, 4176–81

Chikazumi S 1964 Physics of Magnetism. Wiley, New York

Cullity B D 1972 Introduction to Magnetic Materials. Addison-

Wesley, Reading, UK

Fiorillo F, Novikov A 1990 An improved approach to power

losses in magnetic laminations under nonsinusoidal induction

waveform. IEEE Trans. Magn. 26, 2904–10

Hadjipanayis G (ed.) 1997 Magnetic Hysteresis in Novel Mag-

netic Materials. Kluwer, Dordrecht, The Netherlands

Mayergoyz I D 1998 Nonlinear Diffusion of Electromagnetic

Fields. Academic Press, Boston, MA

Pry R H, Bean C P 1958 Calculation of the energy loss in

magnetic sheet materials using a domain model. J. Appl.

Phys. 29, 532–3

Williams H J, Shockley W, Kittel C 1950 Studies of the prop-

agation velocity of a ferromagnetic domain wall boundary.

Phys. Rev. 80, 1090–4

Wohlfarth E P, Buschow H K J 1980–1996 Handbook of Ferro-

magnetic Materials. North-Holland, Amsterdam

G. Bertotti

Istituto Elettrotecnico Nazionale Galileo Ferraris

Turin, Italy

Magnetic Materials: Domestic

Applications

Hard magnetic materials or permanent magnets, and

soft magnetic materials are fundamental to the tech-

nological success of many devices and products, in

particular electric machines and related devices (see

Fig. 1). In modern industrialized western economies

469

Magnetic Mater ials: Domestic Applications