Burton T. (et. al.) Wind energy Handbook

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

difficult and expensive to undertake as they involv e taking the wind farm out of

commission and arranging a temporary earth at the remote end of the current

injection circuit. Also it is becoming increasingly difficult to use a telephone circuit

to provide the remote earth reference as telecommunication companies increasingly

use non-metallic media. However, it is very questionable whether simpler tests give

useful results on large earthing networks with significant series inductance.

10.3 Lightning Protection

It is now recognized that lightning is a significant potential hazard to wind turbines

and that appropriate protection measures need to be taken. Some years ago, it was

thought that as the blades of wind turbines are made from non-conducting material

(i.e., glass reinforced plastic (GRP) or wood-epoxy) then it was not necessary to

provide explicit protection for these types of blades provided they did not include

metallic elements for the operation of devices such as tip brake s. However, there is

now a large body of site experience to show that lightning will attach to blades

made from these materials and can cause catastrophic damage if suitable protection

systems have not been fitted. Of course, if carbon fibre (which is conducting) is used

to reinforce blades then additional precautions are necessary. In response to

damage experienced on sites a number of new standards and recommendations for

the lightning protection of wind turbines have been developed (Cotton et al., 2000,

International Energy Agency, 1997, IEC, 2000a).

Lightning is a complex natural phenomenon often consisting of a series of

discharges of current. The term ‘lightning flash’ is used to describ e the sequence of

discharges which use the same ionized path and may last up to 1 s. The individual

components of a flash are called ‘strokes’.

Lightning flashes are usually divided into four main categories:

• downward inception, negative and positive polarity, and

• upward inception, negative and positive and polarity.

Generally flashes which start with a stepped leader from the thunder cloud and

transfer negative charge to earth (downward inception – negative polarity) are the

most common. Downward negative flashes typically consist of a high-amplitude

burst of current lasting for a few microseconds followed by continuing current of

several hundred amps. Then, following the extinction of the initial current transfer

between cloud and earth there may be a number of restrikes. However, in some

coastal areas there may be a majority of positive flashes of downward inception

which consist of a single long duration strike with high charge transfer and specific

energy content. Upward ince ption is normally associated with very high objects

(e.g., communication towers) and the lightning has very different characteristics.

Although the maximum peak current of this form of lightning is low (some 15 kA)

the charge transfer can be very high and hence has significant potential for damage.

The top of wind turbine blades can now be over 100 m above ground and so there

LIGHTNING PROTECTION 565

is growing concern over the effect of upward negative lightning flashes. Upward

positive flashes are rare.

Table 10.2 shows the parameters normally used to characterize lightning and

some aspects of their potential for damage in wind turbines. The peak current of a

single lightning stroke is over 200 kA but the me dian value is only approximately

30 kA. Corresponding values for charge transfer are 400 C (peak), 5 C (median) and

specific energy 20 MJ= (peak) and 55 kJ= (median). The very large range of these

parameters implies that the initial step in any consideration of lightning protection

of a wind farm or wind turbine is to undertake a risk assessment (IEC, 2000a). The

risk assessment will include consideration of the location of the turbines as the

frequency and intensity of lightning varies considerably with geography and

topology.

Table 10.3 shows some historical data of the frequency of lightning damage

(Cotton et al., 2000). Although this must be interpreted with care, as both wind-

turbine design and lightning-protection systems were evolving rapidly during this

period, the data do indicate the scale of the problem. A large number of the faults

shown in Table 10.3 were due to indirect strokes effecting the wind turbine and

wind farm control systems. Generally the number of faults was dominated by those

to the control and electrical systems while blade damage gave the highest repair

costs and loss of turbine availability, and hence reduction in wind farm revenue.

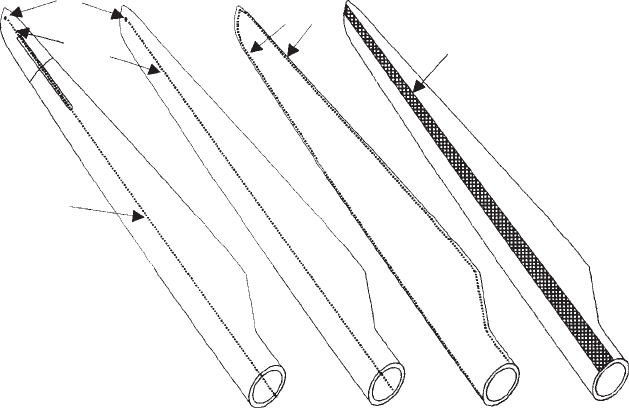

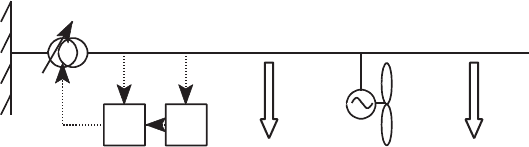

Figure 10.5 shows the techniques commonly used to protect blades against

lightning. The main distinction is whether a limited number of receptors are used to

intercept the lightning (Types A and B) or if an attempt is made to protect the entire

blade (Types C and D). Type A shows how, using one or two receptors at the tip,

the steel control wire of the tip brake may be used as the down conductor. In a

blade without a moveable tip (Type B) then an additional conductor is installed.

Type C has the down co nductor located on the leading and trailing edges although

there are considerable practical difficulties in firmly attaching a suitable conducting

path to the leading edge. Type D shows the use of a conducting mesh on each side

Table 10.2 Effects of Various Aspects of Lighting on a Wind Turbine

Parameter Effect on wind turbine

Peak current (A) Heating of conductors, shock effects,

electromagnetic forces

Specific Energy (J=) Heating of conductors, shock effects

Rate of rise of current (A/s) Induced voltages on wiring, flashovers, shock effects

Long duration charge transfer (C) Damage at arc attachments point or other arc sites

(e.g., bearing damage)

Table 10.3 Wind-Turbine Lightning Damage Frequency (Cotton et al., 2000)

Country Period Turbine years Lightning faults Faults per 100 turbine years

Germany 1991 to 1998 9204 738 8.0

Denmark 1991 to 1998 22 000 851 3.9

Sweden 1992 to 1998 1487 86 5.8

566

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

of the blade. The main mechanism of damage is when the lightning current forms

an arc in air inside the blade. The pressure shock wave caused by the arc may

explode the blade or, less dramatically, cause cracks in the blade structure. Thus,

for effective protection it is essential that the lightning attaches directly to the

protection system and then is conducted safely down the length of the blade in a

metallic conductor of adequate cross section.

Service experience would seem to indicate that the use of a tip receptor works

effectively for blades of up to 20 m in length. There are limited data available for

very large wind turbines but it would appear to be questionable if a receptor only at

the tip will give good protection for very long blades.

Once the lightning current has been conducted to the root of the blade there

remains the problem of ensuring its safe passage to the outside of the tower and

hence to earth. This is not straightforward as it is necessary for the current to pass

across the pitch, shaft and yaw bearings while not damaging the generator and

sensitive control equipment in the nacelle. The present understanding of how

wind-turbine bearings may be damaged by the passage of lightning current is

summarized in IEC (2000a). Generally large, heavily loaded, bearings are unlikely

to be catastrophically damaged although there may be a reduction in their service

life. There is, so far, no effective means of shunting lightning current around a large

bearing as the bearing itself is the lowest inductance path and so the preferred route

for the high- frequency current.

The control and electrical systems are protected against lightning by dividing the

turbine into zones depending on whether direct attachment of lightning is possible

and the magnitude of the current and hence electromagnetic field expected in each

Type A Type B Type C Type D

Receptor

Down

conductor

Steel wire

Down

conductor

Metal mesh

Figure 10.5 Blade Lightning-protection Methods (Reproduced from Cotton et al., 2000, by

Permission of Dr R. Sorenson, DEFU)

LIGHTNING PROTECTION 567

zone (IEC, 2000a). Within each zone components are pro tected to withstand the

anticipated effects of lightning. The principal damage mechanisms to electrical and

control systems are direct conduction and magnetic coupling while the main

protective measures are good bonding, effective shielding and the use of appro-

priate surge protection devices at the zone boundaries.

10.4 Embedded (Dispersed) Wind Generation

The wind is a diffuse source of energy with wind farms and individual turbines

often distributed over wide geographical areas, and so the public electricity

distribution networks, whic h were originally constructed to supply customer loads,

are usually used to collect the electrical energy. Thus wind generation is said to be

embedded in the distribution network or the generation is described as being

dispersed. The terms embedded generation and dispersed generation can be consid-

ered to be synonymous. Conventional distribution systems were designed for a

unidirectional flow of power from the high-voltage transmission network to the

customers. Significant generation was not considered in the initial design of the

distribution network s and alters the way they operate. Connection of embedded

generation to distribution networks has important consequences both for the wind-

farm developer and the operator of the distribution network and is the subject of

continuing interest (CIRED, 1999, CIGRE, 1998, Jenkins, 1995, 1996).

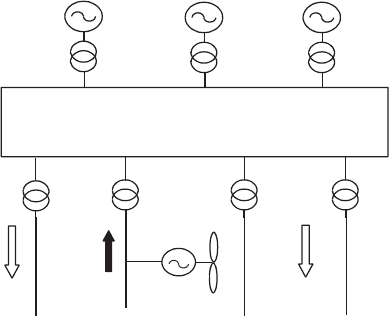

10.4.1 The electric power system

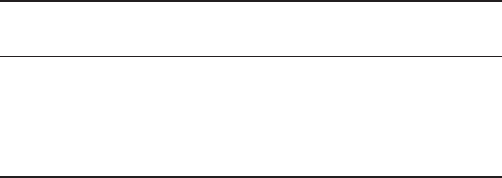

Figure 1 0.6 is a diagrammatic representation of a typical modern electric power

system. The electrical power is generated by large ce ntral generating sets and is

then fed into an interconnect ed high-voltage transmission system. The generating

units may be fossil-fuel, nuclear or hydro sets and will have capacities of up to

Interconnected

transmission network

e.g. 400 kV

Central

generators

Generator

transformers

Bulk supply

transformers

Distribution

network

LoadsLoads

Figure 10.6 A Typical Large Utility Power System

568

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

1000 MW. The generation voltage is rather low (typically around 20 kV) to reduce

the insulation requirements of the machine windings and so each gene rator has its

own transformer to increase the voltage to that of the transmission syst em. The

transmission network is interconnected, or meshed, and so there can be many paths

for the electrical power to flow from the gen erator to the bulk supply transformers.

The bulk supply transformers are used to extract power from the transmi ssion

network and to provide it to the distribution networks at lower voltages. Practice

varies from country to country but primary distribution voltages can be as high as

150 kV. Distribution networks are normally operated radially with a single path

between the bulk supply transformers and the loads. In urban areas with high loads

the distribution networks use large cables and transformers and so have a high

capacity. However, in rural areas the customer load is often small and so the

distribution circuits may have only a limited capability to transport power while

maintaining the voltage within the required limits. Most wind farms are connected

to rural, overhead distribution lines. The design of these circuits tends to be limited

by consideration of voltage drop rather than thermal constraints and this severely

limits their ability to accept wind generation.

10.4.2 Embedded generation

In the early days of electricity supply, each town or city had its ow n generating

station supplying the local load. Thus all generation was local and embedded into

the distribution ne tworks. This arrangement suffered from two major problems: (1)

the generating sets were rather small and hence of low efficiency, and (2) each

station had to keep an additional generator running in case of breakdowns. Then in

the 1930s it was found to be techni cally possib le and cost-effective to interconnect

these individual power stations so that larger, more efficient generating sets could

be used and the requirement for reserve generation could be reduced. Over time,

the size and voltage of the interconnected grid networks increased and so now

voltages of 400 kV and even 765 kV are common and a single grid connects most of

continental western Europe. There have also been significant advances in the

technologies of central generating plant and, for example, large modern combined

cycle gas turbine (CCGT) generating units have efficiencies approaching 60 percent.

However, over the last 10 years there has been a resurgence in interest in

embedded generation stimulated by the need to reduce gaseous emissions from

generating plant. Three major themes may be iden tified: (1) increased development

of combined heat and power (CHP), (2) exploitation of diffuse renewable energy

sources, and (3) deregulation of the electricity supply industry and the separation

of generation and supply of energy from the operation of transmission and

distribution networks.

CHP plants operate at very high overall thermal efficiencies and so reduce the

total fossil-fuel co nsumed and hence the gaseous emissions. In addition to the

existing commercially available technologies there are major development efforts in

very small CHP generators for domestic use and also in the application of fuel cells.

Primary distribution circuits can accept power injections of up to 100 MW and so

most on-shore wind generation is likely to be embedded in a distribution system.

EMBEDDED (DISPERSED) WIND GENERATION 569

There is also considerable interest in much smaller-scale renewable energy schemes,

e.g., individual wind turbines or dispersed wind farms.

Finally, since the mid-1990s many countries have deregulated their electricity

supply systems and separated the production and sale of electrical energy from the

ownership and operation of the transmission and distribution networks. This has

opened new commercial opportunitie s for embedded generation as access to the

distribution network has become easier to obtain and the various costs and benefits

of the electricity supply system have become more transparent.

10.4.3 Electrical distri bution networks

The conventional function of an electrical distribution network is to transport

electrical energy from a transmission syst em to customers’ loads. This is to be done

with minimal electrical losses and with the quality of the electrical power main-

tained. The voltage drop is directly proportional to the current while the series loss

in an electrical circuit is proportional to the square of the current. Therefore the

currents must be kept low which, for constant power transmitted, implies that the

network voltage level must be high. However, high-voltage plant (e.g., lines, cables

and transformers) are expensive due to the cost of insulation and so the selection of

appropriate distri bution network voltage levels is an economic choice.

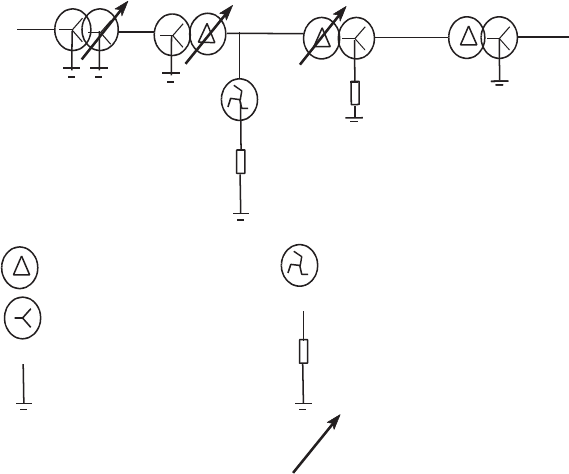

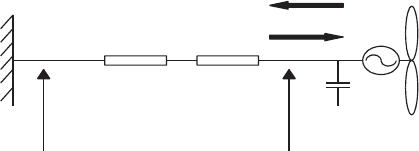

Figure 10.7 is a schematic representation of a typical UK distribution system

although most countries will have similar networks. Power is extracted from the

400 kV

or 275 kV

132 kV 33 kV 11 kV 400V

Delta-connection transformer winding

Star-connection transformer winding

Neutral point connection to earth

Earthing transformer, interconnected star winding

Neutral point connection to earth through an impedance

On load tap changer

Figure 10.7 Typical UK Distribution Voltage Transformation and Earthing Arrangements

570

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

interconnected transmission grid and then transformed down to the primary

distribution voltage (132 kV in this case). The electr ical energy is then transported

via a series of underground-cable and overhead-line circuits to the customers. Mos t

customers typically receive electrical energy at 400 V (for a three-phase connection)

or 230 V (for a single-phase connection). As the power required to be transmitted in

a distribution circuit reduces the circuit volta ge level is lowered by transformers.

The majority of distribution circuits are three phas e although in some rural areas

single-phase circuits are used. Only balanced three-phase netw orks are suitable for

the connection of large wind generators. Three-phase transformer windings may be

connected either in star or in delta and the winding arrangement chosen varies

from region to region and generally follows historical practice. One advantage of

the star connection is that the system neutral point is directly accessible and so can

easily be grounded or earthed. Where a delta winding connection is used an

accessible star point may be created by an earthing transformer. UK practice is to

earth the neutral points of each voltage level at one point only, although in some

continental European countries distribution networks are operated with the neutral

point isolated.

Current passing through a circuit leads to a change in voltage and this is

compensated for by altering the ratio (or taps) of the transformers. 11 kV=400 V

transformers have fixed taps which can only be changed manually when no current

flows. However, higher-voltage transformers have on-load tap changers that can be

operated automatically when load current is passing. The simplest control strategy

is to use an automatic voltage controller (AVC) to maintain the lower voltage

terminals of the transformer close to a set-point (Figure 10.8). The AVC operates by

measuring the voltage on the busbar, comparing it with a set-point value and then

issuing an instruction to the on-load tap changer to alter the ratio of the transformer.

Control systems of this type are unaffected by the presence of wind generators on

the network. Even if the power flow through the transformer is reversed and power

flows from the lower-voltage to the higher-vo ltage network, the control system will

work satisfactorily. This is because the network source impedance is much less than

the equivalent impedance of the wind generators and so the network voltage is

controlled predominantly by the tap changer. Some designs of tap changer have a

reduced current rating if power flows from the low-voltage side to the high-voltage

side of the transformer. However, it is rare for embedded wind generation to

require the full reverse power flow capacity of a transformer on the distribution

network.

AVC LDC

Load Load

VI

Figure 10.8 Voltage Control of a Distribution Circuit (after Lakervi and Holmes, 1995); AVC

- Automatic Voltage Control, LDC - Line Drop Compensation

EMBEDDED (DISPERSED) WIND GENERATION 571

In some distribution networks, more sophisticated control techniques are used to

control the voltage at a remote point along the circuit (Lakervi and Holmes, 1995).

This is a chieved by adding to the local voltage input a signal proportional to the

voltage drop on the network. This is referred to as line-drop compensation (LDC). The

LDC elemen t measures the current flowing in the circuit and applies this to a

simple model of the distribution circuit (i.e., the resistance and inductance to the

point at which the voltage is to be controlled). The resulting voltage is then

subtracted from the local voltage measu rement. In practice, if wind generators are

connected to the network then the current flow in the circuit will be changed, the

effective impedance to the point at which the voltage is to be controlled will alter,

and so the LDC technique will no longer work correctly. LDC is sometimes known

as positive-reactance compounding and a further technique, negative-reactance

compounding, may also not function correctly with embedded generation con-

nected to the circuits. Further discussion of the effect of embedded generation on

transformer voltage controllers is given by Thomson (2000).

The voltage change permitted in 11 kV circuits is small (typically þ/1 percent

or 2 percent) as any voltage variation is passed directly through the fixed tap

transformers to the customers’ supply. In contrast, 33 kV and 132 kV circuits are

allowed to operate over a wider voltage range (up to þ/6 perce nt) as the

automatic on-load tap changes can compensate for variations in network voltage.

Hence, it is common to find that only very limited capacities of wind generation can

be connected at 11 kV as the high impedance of the circuits and relatively large

currents flowing from the generators result in unacceptable variations in voltage.

Determining the size of a wind farm which may be connected to a particular point

in the distribution network requires a series of calculations based on the specific

project data. However, Table 10.4 gives some indication of the maximum capacities

which experience has indicated may be connected. Table 10.4 assumes that the

wind farms are made up of a number of turbines and so the connection assessment

is driven by voltage rise effects and not by power qua lity issues due to individual

large machines.

The electrical ‘strength’ of a circuit is described by its short-circuit or fault level.

The short-circuit level is the product of the pre-fault voltage and the current which

would flow if a three-phase symmetrical fault were to occur. Clearly, this combina-

tion of current and voltage cannot occur simultaneously but the fault level (ex-

pressed in MVA) is a useful parameter which gives an immediate understanding of

the capacity of the circuit to deliver fault current and resist voltage variations. In

Table 10.4 Indication of Possible Connection of Wind Farms

Location of connection Maximum capacity of wind farm

(MW)

Out on 11 kV network 1–2

At 11 kV busbars 8–10

Out on 33 kV network 12–15

At 33 kV busbar 25–30

On 132 kV network 30–60

572

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS

the ‘per-unit system’ the fault level is merely the inverse of the magnitude of the

source impedance (Weedy and Cory, 1998).

10.4.4 The per-unit system

The per-unit system is simply a technique used by electrical power engineers to

simplify calcul ation by expressing all values as a ratio:

actual value (in any unit)

base or reference value (in the same unit)

Its advantages include: (1) a reduction in the appearance of

ffiffiffi

3

p

in the calculations,

(2) that similar per-unit values apply to systems of various sizes, and (3) by careful

choice of voltage bases the solution of networks containing several transformers is

facilitated.

For simple calculations, such as the those required for assessment of wind farms

on simple distribution circuits, all that is required is for these steps to be followed.

(1) Assume an arbitrary base VA (e.g., 10 MVA)

(2) Select voltage bases of each voltage level of the network (e.g., 33 kV and 11 kV).

These voltage bases should be related by the nominal turns ratios of the

transformers.

(3) Calculate the appropriate real and reactive power flows at the generator

terminals as a per-unit value (i.e., for a power flow of 5 MW with the base VA

chosen as 10 MVA, the per-unit value is P ¼ 5=10 or 0.5 per unit, and similarly

for a reactive power flow of 1 MVAr the per-unit value is Q ¼ 1= 10 or 0.1 per

unit).

(4) If necessary, transform the impedances of the circuit from ohmic to per-unit

values using a base impedance of Z

base

¼ V

2

base

=VA

base

.

(5) The base current at any particular voltage level may be calculated from:

I

base

¼ VA

base

ffiffiffi

3

p

3 V

base

.

The per-unit system is used in Example 10.1.

10.4.5 Power flows, slow-voltage variations and network losses

If the output from an embedded wind turbine generator is absorbe d locally by an

adjacent load then the impact on the distribution network voltage and losses is

likely to be beneficial. However, if it is necessary to transport the power through the

distribution network then increased losses may occur and slow-voltage variations

may become excessive.

EMBEDDED (DISPERSED) WIND GENERATION 573

If the wind generator operates at unity power factor (i.e., reactive power Q ¼ 0),

then the voltage rise in a lightly-loaded radial circuit (Figure 10.9), is given

approximately by:

˜V ¼ V

1

V

0

¼ PR=V

0

(10:1)

Operating the generator at a leading power factor (absorbing reactive power) acts

to reduce the voltage rise but at the expense of increased network losses. In this case

the voltage rise is given by:

˜V ¼ V

1

V

0

¼ (PR XQ)=V

0

(10:2)

The source impedance of an overhead 11 kV distribution circuit may, typically,

have a ratio of inductive reactance to resistance (X=R ratio) of 2. An uncompensated

induction generator at rated output, typically, has a power factor of 0.89 leading,

i.e., P ¼2Q. Thus, under these conditions, there is no apparent voltage rise in the

circuit at full power. However, the real power loss (W) in the circuit is given

approximately by:

W ¼ (P

2

þ Q

2

)R=V

2

0

(10:3)

The reactive power drawn by the generator acts to limit the voltage rise but higher

real power losses are incurred in the circuit.

Equations (10.1)–(10.3) for voltage rise and circuit losses are approximate only

and do not apply to heavily-loaded circuits. A simple but precise calculation for

voltage rise in any radial circuit may be carried out using an iterative technique as

follows. (Complex quantities are indicated by bold type.)

At the generator busbar of Figure 10.9 the apparent power (sometimes known as

the complex power ) S

1

is given by:

S

1

¼ P jQ (10:4)

(for a generator operating at lagging power factor, exporting VArs, S

1

would be

given by P þ jQ).

By definition S ¼ VI

, where

indicates the complex conjugate. Therefore the

current flowing in the circuit is given by:

Source

RX

V

0

V

1

P

Q

Figure 10.9 Fixed-speed Wind Turbine on a Radial Circuit

574

ELECTRICAL SYSTEMS