Burt A. The Evolution of the British Empire and Commonwealth From the American Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

South

Africa,

a

Workshop

of

'Native

Policy

295

and another

change

of

governor

put

off the

question

until 1848.

Then

the

million

pounds

that

this war

cost

made

Lord

Grey

warn Sir

Harry

Smith

that

in

the

future

the

colony

would have

to

pay

for

its

own

Kaffir

wars,

which

of

course

implied

self-government;

and

the

energetic

Smith

got

his

advisers to

work

upon

a

plan.

There

were

some

differences

over

details

but not on the broad

fea-

ture

of

representative

without

responsible

government,

the latter to be

excluded

by

the

reservation

of a

large

civil list. When

Grey

got

this

plan,

he

feared it

was

too

liberal

for the

Cape,

and

he

thought

of

emas-

culating

it

by

reserving

the

whole

colonial

revenue,

not

just

a civil

list,

to

be

controlled

by

the

Crown.

Sir

James

Stephen,

whose advice was

still

sought

though

he

had

retired,

said this

would never do because

tradition

had married

taxation

and

representation.

He

frankly

admitted

that

representative

government

at

the

Cape

would be bad

government

but

that

opinion

at

home

and in

the

colony

had made

it

inevitable.

Submitted

to the

Board

of

Trade

Committee of the

Privy

Council,

the

plan

re-emerged

in

1850

with

an

elected

in

place

of

a

nominated

upper

chamber

the

nominated

legislative

council

had

been

very unpopular

in

South

Africa

with

provision

for

dissolution

by

the

governor

of both

chambers

or

just

the

lower

one,

and with

the exclusion of

officials from

election

to either

house,

though they

might

attend and

speak

there,

the

exclusion

being

designed

to

keep

the

executive aloof from

party

strife.

By

this time

crown

colony

government

was

thoroughly

damned at

the

Cape by

the home

government's

attempt

in 1849 to

dump

convicts

on the

colony.

The

attempt,

which was

based

on a

misunderstanding,

was defeated

by

the

solid

opposition

of South

Africans,

British

and

Boer,

Easterner

and

Westerner.

"Passive resistance had

gained

the

day:

a surer indication

of

a

people's

fitness

for

self-government

than

open

rebellion." Like

the

War of

the

Ax,

the even more

expensive

"Seventh"

Kaffir

War,

which

began

in

1850,

increased the mother

country's impatience

with

South

Africa and

the

home

government's

desire

to

make the

colony

pay

the

piper

and call its own

tune; also,

it

delayed

the

implementation

of

the new

constitution,

which

was

ordered

to

be

passed

as

a

Cape

ordinance.

But

Grey

could not

tolerate

the

thought

of

casting

off the

natives,

and his two successors

felt the

same

responsibility

to them.

The

upshot

was that

representative

government

was enacted

in

1853,

but

responsible government

was not

granted

for

nearly

another

twenty years.

CHAPTER

XVII

Australasia

and

Systematic

Colonization

EDWARD GIBBON

WAKEFIELD

and

his

theory

of

systematic

colonization

had

a

powerful

influence

in

building

the

empire

in

Australasia

during

the

1830's and

1840's.

Though

a social and

political

outcast,

he

suc-

ceeded

where

the

highly

respectable

and

strategically placed

Wilmot

Horton had

just

failed,

in

pushing

a rationalized

policy

of

emigration,

because the

parliamentary undersecretary

lacked

the

gift

of

persuasion

that the

scapegrace

possessed

in

abundance. Wakefield had

slipped

and

fallen

when,

in his

eagerness

to

get

money

that he

might

enter

upon

a

parliamentary

career,

he

had

grasped

at

a fortune

by

abducting

an

heiress

from school and

going through

the form of

marrying

her.

Sen-

tenced

to three

years'

imprisonment

in

Newgate,

he

found

himself

in

the

company

of

convicts

bound for

Australia,

including

some who

had

already

been there

as

convicts

and

were

professedly

anxious

to

return.

From

them he learned

all

he

could

of

conditions

in

that distant

land,

and at

the

same time

he

devoured

a

large

mass of

literature

on

colonies.

It

was

then

that

he

pieced

together

his

theory

from

the ideas of

others

and

began

to

expound

it,

under the name

of

another

man,

in

"Letters

from

Sydney,"

published

first

in the

Morning

Chronicle

and later

in

the same

year,

1829,

as

a volume

entitled

Letter

from

Sydney.

Wakefield

insisted that land in

the

colonies

should be

made

available

only

as

it

was

really

needed;

otherwise,

as

had been

all

too

common,

there

would be

a

scramble for

it,

and

private

greed

would retard

the

development

of

the

country

by

dissipating

the

supply

of

labor

and

of

working

capital

and

by

dispersing

settlement in

a most

uneconomical

fashion.

The

proper

formula

was

to hold

the

land

for

sale

at

a

price

high enough

to

prevent

these

evils but

not so

high

as

to

discourage

desirable

purchasers

or

to

cripple

their

resources. The

money

derived

from

the

sales

was to

be

spent

in

sending

out

new

settlers

from

the

Australasia

and

Systematic

Colonization

297

mother

country,

thus

assuring

a

steady

supply

of labor

and sale of

land.

The

emigrants

were

to

be

carefully

selected,

so

that

they

would

be

of

the

right

age

and

class,

and

there

would

be no

surplus

of either sex.

The

whole

concept

was

one

of

balance

and

harmony,

as befitted

that

age

of

Utopian

schemes,

and the

automatic

feature struck

people

as

an

attractive

revelation.

On his

release

from

prison

in

1830

Wakefield

formed

a

colonization

society

to

promote

his

plan.

He

realized that he would

have

to remain

in the

background

because

of

the

stigma

attached to his

name;

but

he

had

a

genius

for

working

through

others,

and he

gathered

a

group

of

converts

remarkable

for their

ability

and

influence. Chief

among

them

were

Lord

Durham,

Charles

Buller,

and

Sir

William

Molesworth,

all

young

and

radical. The

last

named had no

particular

brilliance;

but

his

wealth,

industry,

and voice in the

House

of

Commons

were

very

useful

to the

cause of

systematic

colonization. His

political

reward

came

years

afterward,

in

1855,

when

just

before

his

death

at the

age

of

forty-five

he was

colonial

secretary

for

a

few

months.

Durham,

unlike

the other

two,

did

not owe his

interest

in colonies

to

Wakefield,

for he had

already displayed

it

in 1825

by

organizing

a

New

Zealand

Company;

but

he was

so

impressed

by

Wakefield that

the latter became

a

principal

member of his staff

in

Canada and the author of

the

public

lands

sec-

tion of the famous

Report.

Buller,

outstanding

in the

House of Com-

mons

for his

brilliance,

was Durham's

secretary

on

this

mission,

was

greatly

instrumental

in

getting

the Canadian Union

Act

passed,

and is

best

remembered

as the author of the classic

Responsible

Government

in the Colonies.

The

contemporary

rumor

about

Durham's

Report

that "Wakefield

thought

it,

Buller

wrote

it,

and Durham

signed

it"

was

a

malicious

fabrication;

but

it was also

a

genuine

reflection of the

recognized

abilities

of Wakefield

and Buller.

As a further

indication

of

Buller's

power,

we

may

note

that it was

he

who created

the

long-current

false

picture

of

James

Stephen

mentioned

in an

earlier

chapter.

It

was

the

price

this

worthy

official

paid

for

raising

sensible

objections

to

Wakefieldian

colonization

plans,

and for

his

strict observance

of the

principle

that

a civil servant

should

not

participate

in

public

contro-

versy

even

to defend

himself

against

unjust

attack.

ITbds little

knot of

men,

of

whom Wakefield

was

the

inspiring

center,

exerted

an

influence

out of

all

proportion

to

their number.

This

influ-

ence,

however,

has often

been

exaggerated,

partly

because of

the name

commonly

applied

to

them

"radical

imperialists"

or

"colonial

reform-

ers."

As such

they

have

been

credited

with

being

the

prophets

and

298

CHAPTER

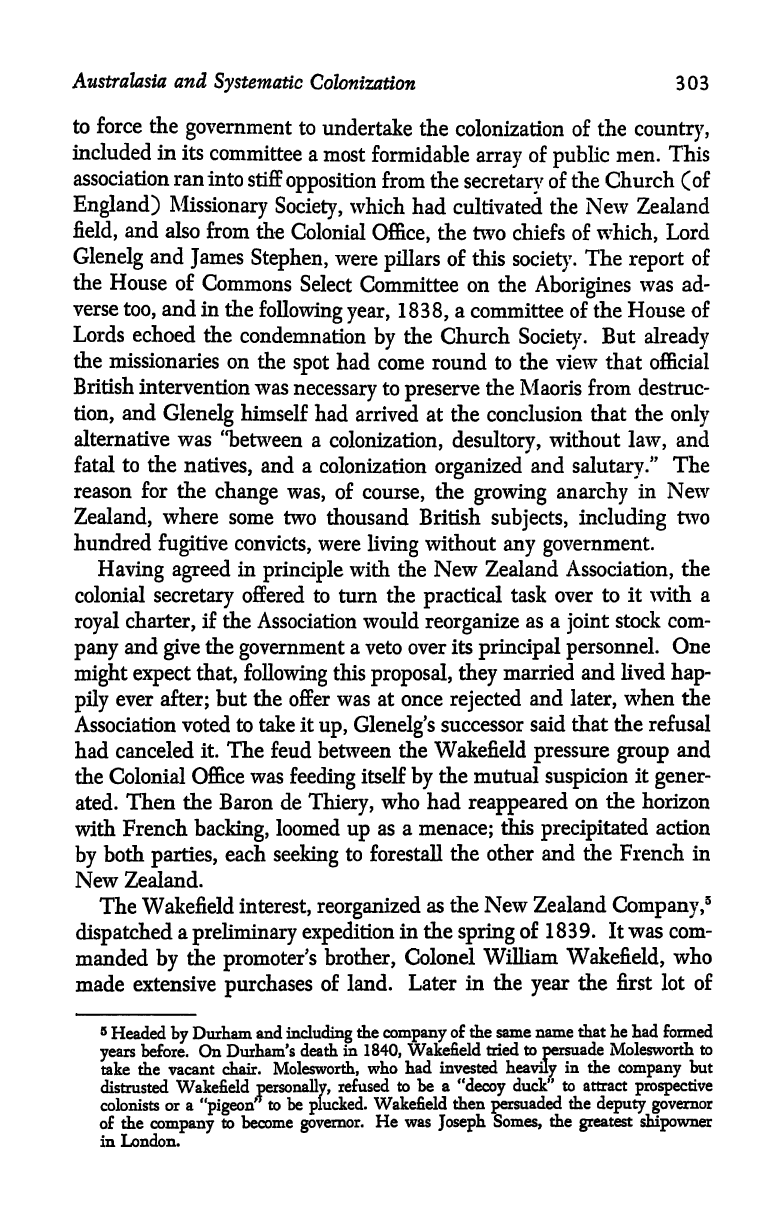

SEVENTEEN:

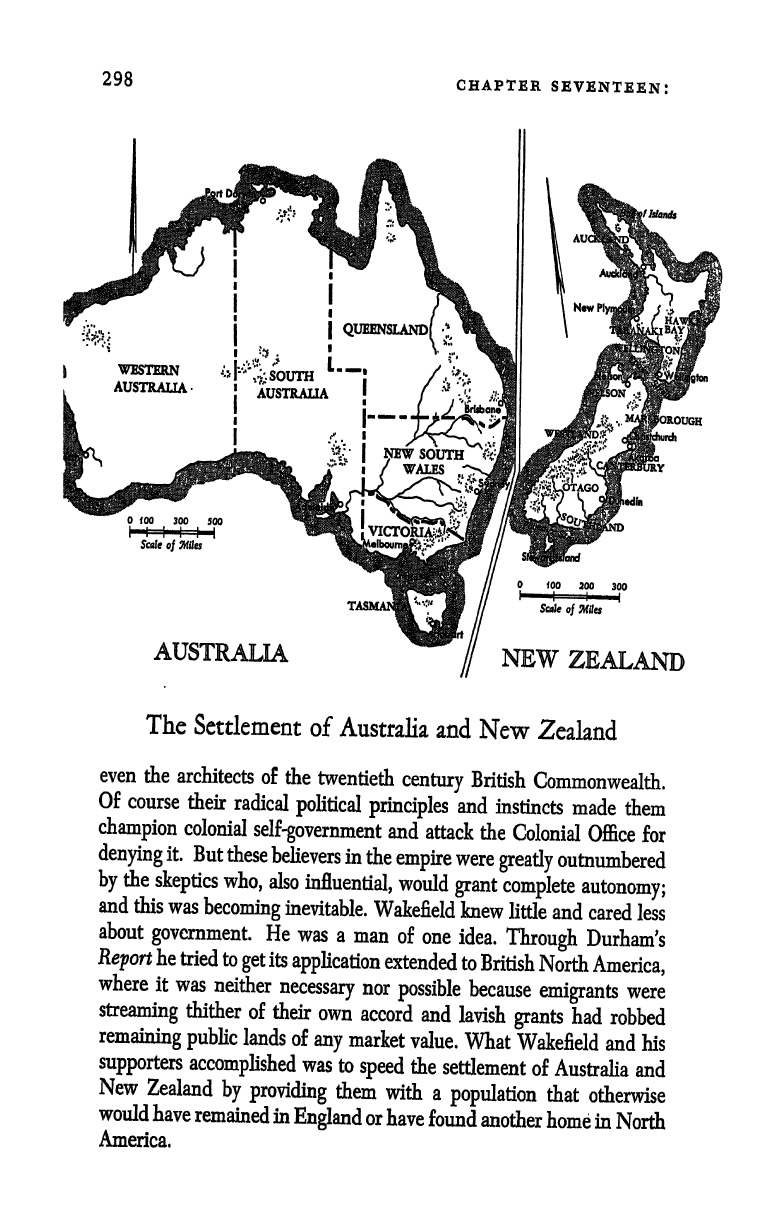

AUSTRALIA

NEW

ZEALAND

The

Settlement

of

Australia

and

New

Zealand

even

the

architects

of

the

twentieth

century

British

Commonwealth.

Of

course

their

radical

political

principles

and

instincts

made

them

champion

colonial

self-government

and

attack

the

Colonial

Office

for

denying

it.

But

these

believers

in

the

empire

were

greatly

outnumbered

by

the

skeptics

who,

also

influential,

would

grant

complete

autonomy;

and

this

was

becoming

inevitable.

Wakefield

knew

little

and

cared

less

about

government.

He

was

a

man

of

one

idea.

Through

Durham's

Report

he

tried to

get

its

application

extended to

British

North

America,

where

it

was

neither

necessary

nor

possible

because

emigrants

were

streaming

thither

of

their

own

accord

and

lavish

grants

had

robbed

remaining public

lands

of

any

market

value.

What

Wakefield

and his

supporters

accomplished

was

to

speed

the

settlement

of

Australia

and

New

Zealand

by

providing

them

with

a

population

that

otherwise

would

have

remained

in

England

or

have

found

another

home

in

North

America.

Australasia

and

Systematic

Colonization

299

The

application

of

the

Wakefield

system

began

in

January

1831

as

the

result

of

the

early

conversion

of Lord

Howick,

the future Lord

Grey

and

colonial

secretary,

who

was

at

this time

parliamentary

undersecre-

tary.

1

A

dispatch

was

then

sent

to the

governor

of New South

Wales

directing

him

to

substitute,

in

place

of the

old

methods

of

granting

lands,

sale

by

auction

at

an

upset

price

of 5

shillings

an

acre,

which was

to

be the

new

system

for

Australia

generally;

and the

Treasury

ad-

vanced

10,000

against

the

security

of

future

sales,

in order to com-

mence

subsidized

emigration

as

soon as

possible.

More than this

amount

was

realized

from

sales

in

1832,

and

many

times more in

the

years

that

followed.

Thus

the

barrier

was

breached that the

high

cost

of the

ocean

passage

to

Australia

had raised

against emigration

in that

direction.

2

New

South

Wales

was

the

chief

beneficiary.

There,

down to

1831,

the

Crown

had

disposed

of

some

three

and

a

third

million

acres for

a

song;

and

then,

from

1832

to

1842,

it

sold

two million

acres for

over

1,000,000,

most

of

which

went

to

bring

out

50,000

new

settlers.

The

result was

that the

population,

which in 1828

had been some

36,000,

nearly

half

of them

convicts,

grew by

1841 to

be about

130,000,

more

than

five

sixths of

them

free. Van

Diemen's

Land,

because

it was

more

devoted to

convicts,

was so

much

less attractive

to free

settlers

that

some were

leaving

it

for

the

mainland,

where in 1835

a

party

of them

founded

the Port

Phillip

settlement,

which later

grew

to be Melbourne.

In 1840 the

island

colony

had

27,000

convicts and

40,000

free inhab-

itants.

Of

the

latter,

however,

two thirds were under

twenty-one.

As

for the infant Western

Australia,

child of

a

capitalist

venture,

nearly

starved

by

a

sterile

soil and

strangled by

a stubborn

forest,

and

a

favor-

ite butt of

jokes by

systematic

colonizers,

that was

a

place

to

stay away

from. So much of its more

eligible

land

was

in

private

hands

and for

sale

at 4.5

pence

an acre that the 5

shilling

price

for less

eligible

land

seemed ridiculous. It had

850 residents

in

1829,

and

2,300

in

1840.

Meanwhile another

Australian

colony

had

been

founded

because

Wakefield

willed

it.

South

Australia was

conceived

as a model

colony

by

Wakefield

and

1

The

new

regulations

have

often

been

called

the

Ripon

regulations,

after

the

secretary

of state who

signed

them.

2

The breach

made it

possible

for Australia

to benefit from adverse conditions

in

North

America.

In

1837

financial

panic

in the

United

States

and

rebellions in

Canada

frightened

many prospective

emigrants

away

from those countries

and

caused a

trebling

of

the stream

to

Australia

in 1838.

This

did not fall off

again

until

four

years

later.

300

CHAPTER

SEVENTEEN:

his

followers.

They

were

coldly

critical

of

the 1831

regulations

as

a

partial

and

distorted

application

of

his

system; they

were

burning

with

enthusiasm

to work it

out

themselves,

free of interference

and

encum-

brances.

The

first

scheme,

for

a

joint

stock

company

chartered

by parlia-

ment,

where it

had

many

friends,

and

empowered

to

rule

the

colony,

was

demolished

by

the

criticism

of

James

Stephen

in 1832.

He

may

have

suspected

what one

of

the

promoters

later

confessed,

that

most

of

them

"intended

to make

money

by

it." The

company

was

replaced

by

an

association,

which

proposed

the

establishment of

South

Australia

as

a

crown

colony

with the

usual

officials,

under the

direction

of

the

Colonial

Office,

and

with

special

commissioners

appointed

by

the

Crown to

manage

the land

sales and

emigration

business.

Official

re-

sistance

to

any

new

colonial venture

that

might

increase the

burden

on

the mother

country

Western

Australia

was

a

fresh

warning

was

.overborne

by

the

pressure

of

the

Wakefield

interest in

parliament,

which

passed

the

South

Australia Act

of 1834

to set

up

the

colony.

This

Foundation

Act,

as it is

also

called,

never

worked

satisfactorily.

The

trouble was not

with the

location

of the

basic

settlement,

for

no

better

place

than

Adelaide

could

have

been

selected. Nor

could

any

fault

be

found with

the

colonists,

the

first

of

whom

were

sent

out

in

1836,

for

they

were

distinctly superior

to

the

average

emigrant

of

that

age

and

might

even rank

with

the

best

of

any

age.

Much

of

the

difficulty

arose from the

gross

incompetence

of

the

board of three

commissioners,

who were

picked by

the

theorists at the

behest

of the

government;

from

the

division

of

authority

between this

board,

which

sat

in

London

and

was

answerable to

parliament,

and the

governor,

who

was

responsible

to the

Colonial

Office;

and from

the

natural

shyness

of

capital,

which

saw

little

chance

of

making

a

killing

in

this

remote

colony.

By

1840,

when the

population

was

just

15,000,

enough

land

had been

sold for

a

population

of

100,000,

and

the

government

of

the

colony

was

bank-

rupt.

But two

years

later

South

Australia was

at

last

finding

its

feet,

the

old

board

of

commissioners

having

disappeared,

the

division

of

power

having

been

followed

by

a

concentration

of it

in the

hands of a

new

and

strong governor,

and

the

imperial

government

having

con-

tributed

225,000

to

restore the

solvency

of the

colonial

government,

which

was

considerably

less

than

what

was

paid

for

the

same

purpose

in

Western

Australia

with

its

much

smaller

population.

Wakefield lost no

prestige

through

the

tribulations

of

South Aus-

tralia.

Disgusted

with

the

way

it

was

being

managed,

he

had

washed

his hands of

the

colony

almost

as

soon as

it was

planted;

and his

re-

Australasia and

Systematic

Colonization

301

markable

ability

for

advertising spread

the

faith

in his

system.

In

1836

he

contrived

to

have

the

House

of

Commons

appoint

a

Select

Com-

mittee on

the

Disposal

of

Colonial

Lands,

to

put

one

of his

disciples

in

the

chair,

to

appear

as

the

principal

witness,

and

virtually

to

shape

the

report.

It

was

before

this

committee that

he

launched his

more

success-

ful

campaign

for

the

colonization

of

New

Zealand,

which

began

when

the

fortunes

of

South

Australia

were

reaching

their

lowest

ebb;

and

his

association

with

the

Durham

mission to

Canada,

which

came

in

the

midst

of

his

New

Zealand

campaign,

gave

him

a

grand pulpit

for

preaching

his

doctrine.

It

was in

response

to

this

preaching

and with an

eye

on

defective

South

Australian

practice,

rather

than

principle,

that

the

tottering

Whig

ministry

created

the

Board

of

Colonial

Land and

Emigration

Commissioners

in

1840,

and

that

the

new

Tory government

passed

the

Waste

Lands

Act

in

1842.

This

board,

which

lasted

until

the

seven-

ties,

3

was

designed

to do

for

the

colonies

generally

what

the South

Australian

board,

at once

superseded

by

it,

had

been

supposed

to

do

for

one

colony.

It

was

never

able

to

function

in

British

North

America,

and it

had

little

scope

in

South

Africa,

to which

it

sent

some

3,500

settlers

by

the

end

of

1850.

Its

chief

concern

was

with

Australia

and

New

Zealand.

The

Waste

Lands

Act,

applying

to all

Australia

and

New

Zealand,

made 20

shillings

an

acre the

uniform

minimum

price

for

land.

Wakefield

had been

horrified

by

the

adoption

of

only

12

shil-

lings

in

South

Australia,

but

the

price

there

and

in

much

of New

South

Wales

was

already

20

shillings.

The

act

also

liberalized

the

prescrip-

tion of

how the

proceeds

of

the

sales

should be

spent.

The

South

Aus-

tralia Act

had

allocated

all

to

emigration,

leaving

nothing

for

other

expenses.

The new

law

released

up

to half

for the

latter

purpose.

Wake-

field had

reached the

zenith

of

his

influence.

But

this

was not

in

Australia. It

was twelve

hundred

miles

away

to the

east.

Wakefield has often been

regarded

as

the

father

of

New

Zealand,

and

in

a

sense he

was.

It

would be

truer,

however,

to

describe

him

as

the

doctor who

presided

at its

birth;

yet

he

was

something

more

than

this,

for he

determined the

shape

and the

character

of the

colony.

God

and

the

devil

had

long

been

competing

for

New

Zealand;

and the

strug-

gle

between them

had

reached

the

point

where,

to

prevent

the

exploita-

tion of the

natives

by

evil white

men

uncontrolled

by

any

government,

it

was

necessary

for some

civilized

power

to

step

in.

The

whole

business

3

By

which time the

growth

of

colonial

autonomy

had

pretty

well

eaten

away

its

jurisdiction.

302

CHAPTER

SEVENTEEN:

shows

up

those who

can

see no

good

in

imperialism,

placing

them

in

the

category

of the

willfully

blind,

along

with the Marxists

who

refuse

to

admit

any

virtue

in

capitalism.

The

native

problem

of New Zealand

was much more

difficult

than

that

of

Australia,

which

hardly

existed

at

all. On

the

other

hand,

it

was

nothing

so

complicated

and

baffling

as that

of

South Africa.

The

Maoris

might

be

more

formidable

fighters

than

any

Bantus,

and

hearty

canni-

bals

to

boot;

but their

numbers

were

limited,

and as

a

race

they

were

far

superior

to

almost

any

other

savages anywhere.

British

and

Ameri-

can

whalers

and

traders

provided

their first

regular

white

contacts,

which

were

not

very

civilizing.

These adventurers were

only

too

glad

to

sell

them

firearms,

thereby

feeding

native

wars,

and

to

buy

a

very

spe-

cial

Maori

manufacture

preserved

human

heads for sale in

the

curio

markets

of

the

world.

The

first

missionaries

arrived

in

1814,

and

these

men of

God found the natives

remarkably apt pupils.

Both

classes

of

white

men,

for their

respective

purposes,

bought

par-

cels of

land from native

chiefs;

and

the

idea

of

buying large

stretches

of

it

for

profitable

development

by

white settlement

became

current

in

the

twenties. The

first to

pursue

it

was a

Belgian

baron

settled in

Eng-

land,

Charles de

Thiery,

who

bought through

an

agent

and then

vainly

sought

government

support.

Among

others who

followed was

J.

G.

Lambton,

the future Lord

Durham,

whose New

Zealand

Company

of

1825

actually

sent out

a

few

settlers. Terrified

by

the

Maoris,

most

of

them

departed

as

quickly

as

they

could.

Meanwhile

other whites

generally

the

offscourings

of the earth

and

particularly

escaped

convicts were attracted to the

islands,

with

the

result

that

wild

iniquities

were

wrought

there. These so scandalized

the

governor

of New

South Wales

that in 1831 he struck at

the

grue-

some and

growing

traffic

in

heads

by

forbidding

their

importation

into

his

colony,

4

and

shortly

afterward he

planted

a British

resident

among

the Maoris to

protect

them.

They

dubbed this

official "the man-of-war

without

guns"

because

he

was

armed

with

only

moral

authority,

which

was not

very

effective

against

the sinners he was sent

to

check. Yet no

other

authority

was

possible

while the British

government

was un-

willing

to

assume

any

responsibility

in or for New

Zealand,

and there

the

anti-expansionist policy

of

the era

was reinforced

by

the mission-

aries,

out

of

regard

for the

welfare

of

the Maoris.

Wakefield's

New

Zealand

Association,

formed

in

the

spring

of 1837

4

Most

of the

vessels

haunting

New

Zealand

waters were

fitted

out

in

Sydney.

Australasia

and

Systematic

Colonization

303

to

force the

government

to

undertake the

colonization of

the

country,

included in its

committee

a

most

formidable

array

of

public

men.

This

association

ran

into

stiff

opposition

from

the

secretary

of

the

Church

(of

England)

Missionary

Society,

which

had

cultivated the New

Zealand

field,

and

also

from

the

Colonial

Office,

the two chiefs of

which,

Lord

Glenelg

and

James

Stephen,

were

pillars

of

this

society.

The

report

of

the

House

of

Commons

Select Committee

on the

Aborigines

was ad-

verse

too,

and in

the

following

year,

1838,

a

committee of the

House

of

Lords

echoed the

condemnation

by

the

Church

Society.

But

already

the

missionaries

on

the

spot

had

come round

to the view that

official

British

intervention was

necessary

to

preserve

the Maoris

from

destruc-

tion,

and

Glenelg

himself

had

arrived

at the conclusion

that the

only

alternative was

"between a

colonization,

desultory,

without

law,

and

fatal

to

the

natives,

and

a

colonization

organized

and

salutary."

The

reason

for

the

change

was,

of

course,

the

growing

anarchy

in

New

Zealand,

where

some

two

thousand

British

subjects,

including

two

hundred

fugitive

convicts,

were

living

without

any

government.

Having agreed

in

principle

with the

New Zealand

Association,

the

colonial

secretary

offered

to turn

the

practical

task

over to

it with a

royal

charter,

if the Association

would

reorganize

as

a

joint

stock

com-

pany

and

give

the

government

a

veto over

its

principal personnel.

One

might

expect

that,

following

this

proposal,

they

married and

lived

hap-

pily

ever

after;

but the

offer

was at once

rejected

and

later,

when the

Association voted to take

it

up, Glenelg's

successor

said

that the

refusal

had canceled

it.

The

feud between

the Wakefield

pressure

group

and

the Colonial Office

was

feeding

itself

by

the mutual

suspicion

it

gener-

ated.

Then

the

Baron

de

Thiery,

who had

reappeared

on

the

horizon

with

French

backing,

loomed

up

as a

menace;

this

precipitated

action

by

both

parties,

each

seeking

to forestall

the other and

the French

in

New

Zealand.

The Wakefield

interest,

reorganized

as

the New Zealand

Company,

5

dispatched

a

preliminary

expedition

in the

spring

of 1839.

It

was com-

manded

by

tie

promoter's

brother,

Colonel

William

Wakefield,

who

made

extensive

purchases

of land.

Later in the

year

the first lot

of

5

Headed

by

Durham

and

including

the

company

of the same

name that

he

had formed

years

before. On

Durham's

death in

1840,

Wakefield

tried to

persuade

Molesworth

to

take the vacant

chair.

Molesworth,

who had invested

heavily

in

the

company

but

distrusted

Wakefield

personally,

refused

to be

a

"decoy

duck"

to attract

prospective

colonists

or

a

"pigeon

to

be

plucked.

Wakefield

then

persuaded

the

deputy governor

of

the

company

to

become

governor.

He was

Joseph

Somes,

the

greatest

shipowner

in London.

304

CHAPTER

SEVENTEEN:

settlers

embarked for

New

Zealand.

They

landed

at Port

Nicholson,

later

Wellington,

in

January

1840.

A week

later,

Captain

William

Hobson

of

the

Royal Navy

arrived

in the

Bay

of

Islands,

several

hun-

dred

miles

to the

north,

to

negotiate

with the Maoris

for

the

recognition

of

British

sovereignty.

Another

week

later,

with

the decisive aid

of

the

missionaries,

of

whom

Henry

Williams,

a former naval

officer,

was

out-

standing,

Hobson

persuaded

the

assembled chiefs

to

sign

the

Treaty

of

Waitangi.

Thereby

the chiefs

formally

ceded

the

sovereignty

of

their

territories;

the

Crown

guaranteed

them

and

their

people

the

possession

of

their lands

and other

property;

the

chiefs bound themselves

to

sell

no

land

except

to

the

Crown;

and

the natives

acquired

the

rights

of

British

subjects.

In

May,

for further

security,

Hobson

established

an

alternative

British title

to

the islands

by proclaiming

British

sovereignty

over

them.

In

August

a

French

expedition

that had sailed

in

March

arrived

to

plant

a

colony

on the

South Island but

withdrew,

after

land-

ing

some

settlers,

because

the commander

shrank

from

challenging

the

British title.

6

Still

the

Colonial Office would

not

recognize

the

New

Zealand

Company.

But

before the end of the

year

Wakefield's astute

publicity

and

wire-pulling

produced

an

agreement

by

which

the

com-

pany

was to

receive

a

royal

charter and land

at the

rate

of one acre

for

every

5

shillings

it

spent

on

colonization.

The settlement

of

New

Zealand was slower and less

systematic

than

its

planners anticipated.

This was

partly

the result of their

own

bad

management.

As in South

Australia,

much

land

was

sold

to

absentees

for

speculation

and

much to

settlers before it

was

surveyed.

The

great-

est

cause

of confusion

and

delay

was the

company's inability

to deliver

titles,

and

this

in turn

arose from the

government's

solicitude for

the

Maoris.

For their

protection

Hobson's instructions

required

him,

on

his

arrival,

to

proclaim

that

no

private

title to land would be

valid

un-

less

granted

or confirmed

by

the

Crown. This struck at all

purchases by

private

individuals

from the Maoris

before as well

as

after

annexation,

and it

necessitated a review to determine

what

should be

confirmed and

what should

not.

Conflicting

claims to

the

same

land,

different

natives

having

sold

it

to

different

whites,

also

called

for

adjudication.

A

com-

mission

was

appointed

to

straighten

out the

tangle,

and

the

work

began

nicely.

Then the second

governor,

an

injudicious

man,

magnified

the

difficulty by

creating

a

whole new

class

of

claimants.

Alarmed

by

growing

Maori resentment

against

the

treaty

ban

on

sales

to

private

6

Hie

English

company

eventually

bought

out the land claims

of the French

company

for4,500.