Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

272 Richard Salvucci

Summerhill’s social savings calculations are a piece of this argument,

ranging from 6 to 11 percent of GDP in 1913 on freight, and a surprisingly

large 4 percent for passenger service (versus, say, something on the order of

1.5 percent for Mexico). Summerhill’s conclusions, although cautious, point

to an obvious fact. In Latin America, railroads mattered for growth and, in

some places, they mattered a great deal. That this finding emerges should

perhaps not surprise, for the tradition of structuralist economic thinking

so long current in the region has always emphasized sluggish adjustments

in supply as a primary obstacle to economic development, and public, as

opposed to private enterprise as its agent. These putatively large returns to

railroad construction in the presence of insecure property rights, political

upheavals, and undeveloped capital markets go some way to explaining why

railroads as, so to speak, engines of economic growth, went nowhere for

many years: the divergence between private and social rates of return was

simply too great. Domestic investors, capital-constrained, and, perhaps,

alert to the true risks of investing, were unable or unwilling to seize the

opportunities offered. Foreign investors, inevitably cautious, regarded some

of these markets with great trepidation. For most of the nineteenth century,

or at least after default in 1827, the risk premium on Mexican bonds was

rarely less than 10 percentage points above the yield on British consols, and

when the yield on Mexican bonds did converge to the consol rate in 1887,it

was for the first time in nearly a quarter century. For Argentina, significantly,

the perceived risk was considerably lower, and, according to calculations by

Cort

´

es Conde, country risk was usually less than 10 percentage points after

1864,except in moments of severe strain. Hence, Argentina’s earlier start

in railroad construction, and a larger network in 1877 than Brazil, Chile,

Peru, and, of course, Mexico, which had almost nothing. Because the bulk

of railroad construction that occurred after 1870 depended on capital from

Great Britain, the United States, and France, the attitude of foreign investors

toward the principal railroad-building countries was, essentially, a decisive

consideration.

Colombia was somewhat different. Here, recent estimates by Mar

´

ıa

Te resa Ram

´

ırez for 1927 place the social savings for Colombia between

2 and 4 percent of GDP, by far the smallest estimate thus far for

Latin America. Perhaps the simplest explanation is that the measure of

social savings depends on the existence and cost of alternative means of

transportation. Because railroads were constructed with some delay in

Colombia, road and highway transport was already available, reducing the

share of coffee transported by railways and raising the responsiveness of

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 273

shippers to fluctuations in the price of rail transportation. And finally, the

railroad in Colombia did not form a true network, as it did in Argentina, or

to a lesser extent, in Brazil, Chile, and Mexico. Most were built to link up

to the Magdalena River, and the effect they had in knitting together mar-

kets across the country – one with very difficult geography – was blunted.

For this reason, then, railroads in Colombia highlight the conditions under

which rail development was important for economic growth in Latin Amer-

ica. In Central America, too, the railroad has been considered less important

from the standpoint of social savings than elsewhere, even if the region was

said to have experienced a “transportation revolution” in the second half

of the nineteenth century. Other places, such as Ecuador, had little or no

railroad development, and in Venezuela, most railroad building took place

between 1880 and 1900, with little occurring thereafter.

An issue that is closely related to the impact of railroads on economic

development, but perhaps requiring separate comment, is the transfer of

public or communal lands to private control that often occurred in response

to or in conjunction with the extension of railways. In Bolivia, Mexico,

and Peru, at various times from the 1870s and 1880s (in Mexico) to the late

nineteenth and first decade of the twentieth century (Bolivia and Peru), the

economic growth experienced by regions first linked by rail to new markets

provided both the incentive and the means to expropriate the lands of free

villages. In Mexico, the spread of the rail network and the privatization

of public lands by survey companies were clearly related, if only as two

expressions of a general policy, the goal of which was to promote Mexico’s

commercial development. More concretely, there is visually compelling

correspondence between those parts of the country (in the north) where the

survey companies were very active and the construction of rail trunk lines.

The figures are striking. During the Porfiriato, nearly 11 percent of Mexican

territory was given over to the land-survey companies in compensation.

In Central America, the history of the expropriation of village lands

after 1870 is well known, and in Guatemala, for instance, the wholesale

transfer of “unproductive” lands given over to maize being switched to

the increasingly profitable cash crop of coffee has been studied in great

detail. Yet, whatever one makes of these developments, it is very difficult to

credit them with the character of an ostensibly commercial phenomenon –

that resources and output that were previously mobilized and allocated

outside a market framework were now more “efficiently” employed. A

persuasive analysis by H

´

ector Lindo Fuentes of price dispersion among

subsistence commodities such as maize shows substantial uniformity in

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

274 Richard Salvucci

prices across villages in El Salvador, which Lindo Fuentes takes to be evi-

dence of the market embeddedness of transactions. The same held true

in Colombia, where peasant producers brought tobacco, sugarcane, cot-

ton, and cacao to markets throughout the countryside. Whatever else elites

accomplished during this burst of entrepreneurial energies, they did not

bring the discipline or efficiency of the market to bear on these agricul-

tural economies for the first time. Thus, it seems that a simple equation

of the spread of private property in land with material progress confuses

changes in distribution with changes in output, or at the very least, over-

states the growth in product, and obscures the deterioration in the distri-

bution of wealth. Generalization is difficult because the impact of these

policies on vast expanses of largely empty land on the northern Mexican

steppes would be very different from what occurred, in, say, the coffee

plantations of the densely populated regions in highland Guatemala, or in

Santander and Antioquia in Colombia. Yet even in Mexico, pressure on

village lands became increasingly powerful as the commercial potential of

crops such as sugarcane came to bear on village lands in Morelos during the

Porfiriato.

Nor was the phenomenon restricted solely to the indigenous heartlands

of Mesoamerica. McGreevey, although fixing no dimensions on the pro-

cess, concludes that the collective appropriation of village, public, and

church lands in the second half of the nineteenth century in Colombia was

extremely significant. Here, the transfer of such lands was linked to the

rise of an export commodity, tobacco, in the lowlands and to the expan-

sion of cattle ranching in the highlands for the domestic market. More-

over, because the scale requirements of tobacco production were large, the

spread of tobacco cultivation raised income and land values dramatically,

but concentrated them as well. Catharine LeGrand emphasizes that much

of Colombia’s national territory was, strictly speaking, not titled until well

into the nineteenth century and that the dimensions of the transfer of

public lands into private hands was enormous, something like 2.4 million

hectares of land between 1870 and 1930.InArgentina, too, as Carl Solberg

has written, much new land came on to the market in the 1860s and

1870s, when the provinces rolled back the Indian frontier and acquired

vast new expanses of public land, much of which ended up in the hands

of the cattlemen who comprised the backbone of the rural oligarchy, the

whole undertaking perhaps symbolized by General Julio Roca’s “conquest of

the wilderness” in 1879, and substantial sales of public land would continue

well after that date.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 275

Although these pressures (and usurpations) reflected changing valuations

that producers placed on land, they also highlight the importance of popula-

tion for economic growth. Historically, efforts to dispossess villages of land

in Colombia, Mexico, and Central America were also efforts to drive their

populations into a labor market by rupturing the ancient nexus between

Indians and peasants, and their lands. There was nothing new about these

efforts in the period after 1870 save, perhaps, the aggressiveness with which

they were undertaken under the stimulus of increased international com-

modity demand. Labor rather than land had, by and large, become the

scarce factor of production in the massive depopulation that followed what

Alfred Crosby termed the “Columbian Exchange.” Where attachment to

village life made peasants reluctant to enter the rhythms of commercial

production, or where population centers lay distant from the demands of

highland mines or lowland plantations – as they did, for example, in Peru (in

cotton growing) and Central America (in bananas) – extra-market devices

featuring a variety of names had become common means of acquiring labor.

In an economic sense, these were structural problems, a mismatch between

labor supply and demand. In the period after 1870,ascommercial opportu-

nities and pressures intensified, new means of acquiring or enlarging labor

forces became widespread. Because African slavery faced extinction in the

Spanish Caribbean in 1870 by the Moret Law, or in Brazil by abolition in

1888, the response was essentially limited to the use of free labor, although

freedom in this context must be interpreted circumspectly. By the same

token, because the natural rate of population growth in Latin America was

relatively slow, immigration frequently became a crucial source of labor,

especially in Argentina, where inexpensive labor was a critical element in

the success of pampean agriculture. It is, therefore, necessary to spend some

time considering the importance of population for economic development

in this period.

In theory, all changes in production could be attributed to changes in

the size of the labor force (an increase in total output), or in productivity

per member of the labor force (an increase in per capita output), or both.

Practically speaking, population increase is a way of estimating growth in

the labor force because, as things stand, the data from this period are not

likely to yield much more. It is also, perhaps, useful to consider the quality

of labor and, particularly, the extent to which education did or did not

augment productivity. Recent findings suggest that Latin America, in this

regard, had also fallen well behind more advanced nations of the Atlantic

economy by the late nineteenth century. Finally, where it is possible to

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

276 Richard Salvucci

Table 7.5. Population growth rates

(percent per year)

Argentina, 1889–1930 3.1

Brazil, 1890–1929 2.1

Chile, 1870–1930 1.6

Colombia, 1843–1912 1.5

Mexico, 1895–1930 0.75

Peru, 1896–1928 2.2

Venezuela, 1870–1930 1.1

Source: Based on author’s calculations.

identify them, changes in demographic structure may also shed light on

larger patterns of economic growth, as they crucially do in Argentina.

As the data in Table 7.5 suggest, population growth in Latin America

in this period was highly uneven. For purposes of discussion, it is possi-

ble to distinguish between those countries whose populations grew quite

slowly, those that increased at a more typical rate, and those whose demo-

graphic growth was truly rapid. The median rate of growth, given the

uncertainties in the data, seems to be about 2 percent or so, with Mexico

and Colombia at the lower end of the scale, Argentina at the upper, and

Brazil, Chile, Peru, and Uruguay at various intermediate levels. There

is naturally a reasonably strong association between the rate of popula-

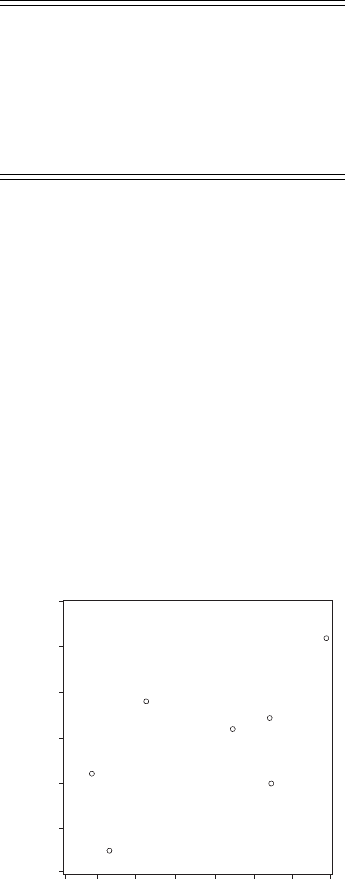

tion growth and GDP growth in this period (see Figure 7.1). The scatter

Growth of Per Capita Income

Growth of Population

3.5

3.0

2.5

2.0

1.5

1.0

0.5

0.0 0.5 1.0

1.5 2.0 2.5

3.0

3.5

Figure 7.1.Growth of population and per capita income.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 277

diagram displays the association for those countries for which we have

data, and it is strongly positive, with a simple correlation between popu-

lation and output growth of 0.92.Perhaps more important, there is also a

positive association between population growth (in logs) and per capita

income growth (the difference between the logs of output and popu-

lation growth), with a simple correlation of 0.78. Countries with more

rapidly growing populations also had higher income growth per head.

The result is not as unusual as it might seem. In the long run, with the

extension of rail networks and, hence, the frontiers of commercial agricul-

ture, more people had more, rather than less, land and capital with which

to work, so diminishing returns did not occur. Juan Bautista Alberdi’s

(1810–84) celebrated aphorism, “to govern is to populate,” makes perfect

sense in this context. Nor is the result dependent strictly on the data we have

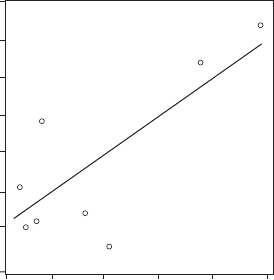

collected. A similar exercise linking per capita GDP in 1913 to the growth

rate of population between 1870 and 1913 for eight countries (Argentina,

Brazil, Chile, Colombia, Mexico, Peru, Uruguay, and Venezuela) in 1990

international dollars drawn from Angus Maddison’s The World Economy

produces similar results (see Figure 7.2). Population growth raised rather

than lowered per capita income in the period between 1870 and 1930.

Where natural increase substantially comprised the bulk of population

increase, as it did in Mexico, demographic change was painfully small.

Robert McCaa has estimated that the annual growth rate of the population

Population Growth Rate

GDP Per Capita

4000

3500

3000

2500

2000

1500

1000

1.0 1.5 2.0

2.5 3.0 3.5

500

Figure 7.2. GDP per capita (1990 international dollars) in 1930 versus population growth

rate 1870–1913.

Source: Maddison, The World Economy, 193, 195.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

278 Richard Salvucci

there between 1876 and 1910 was no more than 1.71 percent, and after 1900,

the rate slowed to 1.09 percent. The Revolution, according to McCaa,

produced a demographic disaster, perhaps the worst since the sixteenth

century, with population falling by one million (total population in 1910 was

about fifteen million). Total growth from 1910 through 1930 was no more

than 1.4 million, or less than the increase for 1900–10.Demographic growth

per se could have therefore done little or nothing to raise total output, and

Mexico was not, and had never been, a magnet for foreign immigration.

So in some portions of Mexico, such as the Yucat

´

an peninsula, which were

remote from major population centers or from poles of economic growth

to which workers could migrate (the proximity of northern Mexico to

the United States is the usual example), relative labor scarcity in the face

of growing commercial demands produced a history of repression on the

henequen plantations. Yet what was true for henequen was not invariably

the case for other commodities. Sugarcane planters in Morelos may have

despoiled villages of their lands, but they also substituted capital for labor in

producing and processing sugar. Over time, this industry actually required

not more but relatively less labor, a fact reflected in both census data and

in the nature of agrarian protest during the Mexican Revolution. Still,

Mexico’s overall record of growth between 1895 and 1930 suggests that slow

population increase was an obstacle to economic growth.

Colombia, too, experienced relatively slow population growth, with an

overall average between 1870 and 1930 of something just over 1 percent

per year. Catharine LeGrand suggests that immigration into Colombia

was not large, and that the creation of an adequate labor force under the

pressure of export expansion was inevitably difficult, particularly when it

involved peasants who migrated into frontier regions. Hacendados from

western Cundinamarca and Tolima imported workers from the eastern

highlands through a system of labor contracting called enganche.But there

were also widespread conflicts in the interior, in western Colombia, and

along the Caribbean coast between peasants settled on public lands, known

collectively as colonos, and land entrepreneurs interested in developing lands

for cattle ranching, the production of forest products, or coffee plantations.

Again, there is no reason to assume that an increase in the export surplus

measures the increase in domestic output because it is clear that the peasant

population was not entirely outside the market economy to begin with.

Rather, the effort to appropriate previously untitled (but hardly vacant)

lands was designed to mobilize a labor force adequate to the needs of an

export economy in which a rural proletariat was absent and population

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 279

growth was slow. Thus, LeGrand concludes, “in order to generate a labor

force (italics mine) ...entrepreneurs logically sought to turn the public lands

into private properties ...The fact that the population of Colombia was

much smaller . . . accounts in part for the difficulties large proprietors had

in acquiring labor.”

7

Chile, too, experienced slow population growth, at a rate of about 1.6

percent per year. Nevertheless, Arnold Bauer has suggested that economic

expansion under the stimulus of external demand, first in wheat and later

in the export mining sector of nitrates and copper, was not significantly

hindered by labor shortages experienced elsewhere in Latin America because

“Central Chile ...was an area with plentiful if idle hands.” Indeed, Patricio

Meller estimates that nitrate exports grew at something over 6 percent per

year between 1880 and 1930, and Carmen Cariola and Oswaldo Sunkel

point to the “spectacular” population growth in the Norte Grande that

facilitated the growth of nitrate exports.

Peru experienced somewhat more rapid demographic increase. The

annual rate of population growth between 1876 and 1940 was in the neigh-

borhood of 2 percent yearly, and after the termination of Chinese inden-

tured immigration in 1874, immigration did not figure importantly. In

Peru, too, the rise of sugar plantations on the north coast in the valleys of

Lambayeque, Jequetepeque, Chicama, and Santa Catalina presented major

problems of labor recruitment, a difficulty addressed to some extent by the

rise of the infamous enganchadores,orlabor contractors, who facilitated

migration from the Sierra to the coast. Peter Klar

´

en refers to the “critical

shortage of labor” in the emerging sugar industry, concluding that an ade-

quate supply of labor had long been a major problem for the region’s sugar

planters.

Like Peru, Brazil’s population grew at roughly 2 percent between 1872 and

1940,orfrom about 9.9 million to 41.2 million people. But a few distinct

features of demographic change require comment. Unlike Mexico and Peru,

Brazil experienced substantial immigration, with the total flow between

1870 and 1920 amounting to about 3.3 million persons, of whom 1.4 mil-

lion, or some 42 percent, were of Italian origin, followed by lesser but still

significant numbers of Spaniards, Japanese, and Arabs. There was a pro-

nounced tendency for immigration to increase in the wake of the abolition

of African slavery. Immigration exceeded 100,000 for the first time in 1888,

7

Catherine LeGrand, Frontier Expansion and Peasant Protest in Colombia, 1830–1936 (Albuquerque,

NM, 1986), 38, 40.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

280 Richard Salvucci

and something in excess of a million immigrants were to follow in the

1890s, with more than 200,000 in 1891 alone. As Nathaniel Leff observes,

the connection between the abolition of slavery and the rise of immigration

was not circumstantial but purposeful because the coffee planters of S

˜

ao

Paulo pressured the central government and the province of S

˜

ao Paulo to

subsidize European immigration and to ensure an elastic supply of labor in

the face of abolition. Thus, in Leff’s view, the abolition of slavery in Brazil

did not have the same effects on the labor supply that it did in the U.S.

South after the Civil War. As Leff put the matter, labor markets in Brazil

differed because “shifts in the demand curve for labor determined shifts in

the supply schedule of workers,” something that seems quite different from

what occurred in Mexico and Peru. As a result, Brazilian income growth

in 1890–1929 was a respectable 4.3 percent per year. Still, the emergence

of large estates on the Brazilian coffee frontier was accompanied by the

expropriation of settlers who were expelled onto public lands farther in the

interior in a process that LeGrand explicitly compares with Colombia.

THE IMPACT OF DEMAND

Variations in production, prices, and employment in the short run are typ-

ically attributed to fluctuations in demand because its determinants can

change relatively quickly. Political upheavals and monetary disturbances

can occur suddenly and with little warning, the result of the vagaries of

regime changes, an untoward mining discovery (e.g., gold in California

and Australia in 1849), or legislation affecting the supply and demand of

precious metals under the gold and silver standards (e.g., that undertaken

by the Latin Monetary Union between 1865 and 1878). At the same time,

variations in international commodity prices, which could to some extent

be taken as given (the major exception, of course, would be Brazilian cof-

fee and the valorization schemes, wherein Brazil, with its large share of

the global market, sought to support the price of coffee by reducing its

supply), could vary rapidly and unexpectedly from year to year as well, pre-

senting producers with a rapidly evolving picture of demand. Indeed, to an

extent, the leitmotiv of discussions of the commodity cycle is the variabil-

ity of prices, something that Bulmer-Thomas has termed the “commodity

lottery.” Yet a composite picture of these forces, by definition, would be

difficult to provide because they are as varied as the countries whose history

we have chosen to analyze. But some attempt at generalization is necessary

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 281

to make the story intelligible and coherent rather than episodic, disjointed,

and anecdotal.

Oneofthe best-known discussions in the literature of economic develop-

ment is the question of the terms of trade, or the relative prices of exports. In

essence, the net barter terms of trade is the measure most commonly com-

puted because it is the one for which data are most readily available, and,

hence, the framework within which comparisons are routinely, if some-

times facilely, made. The subject is of particular relevance to the history of

Latin America because the terms of trade literature is traditionally associ-

ated with the work of the distinguished Argentine economist, Ra

´

ul Prebisch

(1901–85). At a basic level, an “improvement” in the terms of trade – that

is, an increase in the price of exports relative to imports – represents an

increase in real income for the exporting country because the relative price

of exports improves. “Deterioration,” on the other hand, implies that real

income has fallen. In the history of Latin America, the notion of deterio-

rating terms of trade has sometimes served as a justification for the rejec-

tion of liberal economic prescriptions that rely on free trade as an engine

of growth because under such conditions, trade could ostensibly become

impoverishing. By extension, attempts to alter comparative advantage, such

as import substitution industrialization, seem logical if demand for a com-

modity – and hence its relative price – is falling. This explains the historical

importance so often ascribed to the analysis of the net barter terms of

trade.

Whereas accounts of the terms of trade are frequently carried out at a

high level of aggregation, it makes some sense to proceed at the country

level when the commodity composition of exports differs, as it did in

Latin America, even if variations in income in the developed (importing)

countries imposed some measure of correlation on export price movements

in Latin America. And, given the limits of the data, a striking heterogeneity

in country experience in the period 1870 through 1930 is apparent. There

was no overall tendency for the net barter terms of trade to deteriorate,

even if each country did experience episodes of deterioration, and even

if some countries, most notably Mexico and Peru, did experience falling

terms of trade after 1870. This is especially important when one considers

that studies of the period before 1870 reveal much the same thing. In other

words, for roughly the first century of their independence, the nations

of Latin America, considered on the whole and individually, experienced

growing rather than declining demand for their tradables if the relevant

metric is the net barter terms of trade.