Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

262 Richard Salvucci

fluctuations emphasized by Ford in his study play little or no role in this

model of balance of payments adjustment under the gold standard. In fact,

della Paolera and Taylor argue that macroeconomic performance under the

gold standard in Argentina was especially good, with average annual real

growth of 5.8 percent and annual inflation of 2.6 percent between 1899 and

1914. They nevertheless, however, suggest that the system was extremely

vulnerable to external shocks that came with World War I and the collapse

of the gold standard, and to a weak financial system that could not maintain

the fixed exchange rate when international pressures intervened.

The strongest arguments made in favor of silver or, in effect, against

the gold standard, have been advanced by Rosemary Thorp and Geoffrey

Bertram in their work on Peru, with concurrence from Alfonso Quiroz.

It is important to understand that the price of silver in terms of gold fell

dramatically after 1872,fromroughly $1.32 (measured in United States

gold coin of an ounce, 1,000 fine, taken at an average price in London)

to $0.59 in 1898,orafall of more than 55 percent. This amounted to a

very substantial devaluation for those countries on silver, and its impor-

tance is recognized by Thorpe and Bertram as a cause of the growth of

Peruvian exports. Conversely, the devaluation of silver raised the price of

import-competing goods, such as textiles, which provided a distinct impe-

tus to import substitution. By the same token, Thorp and Bertram attribute

something of the slowdown in Peruvian growth to Peru’s move to the gold

standard after 1897, which was explicitly opposed by agro-exporters, min-

ers, and business interests associated with them but supported by financial

interests concerned with the preservation of their capital. However, even in

this case, Quiroz has observed that exchange volatility created uncertainty,

and that uncertainty, in turn, was transmitted to the real economy.

One can make similar arguments for Colombia, Central America, and

Mexico. H

´

ector P

´

erez-Brignoli notices that a rapid upswing in exports from

the region, where all five countries remained on silver into the twentieth

century, ended in 1897, followed thereafter by relative stagnation. The avail-

able statistical evidence, crude to be sure, is consistent with the hypothesis

that the depreciation of the exchange rate stimulated exports, although

the rate of export growth in Costa Rica appears to have been significantly

higher than elsewhere. Colombia was effectively on the silver standard from

1850 through 1885.Because of intervening political difficulties and mon-

etary complexities, the evidence relating depreciation to export growth is

not unambiguous, but the volume of exports in Colombia (measured in

terms of gold pesos) doubled between the mid-1870s and the late 1890s, a

rate of growth of about 3 percent per year.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 263

A similar upswing in Mexico is evident after 1877 as well, although the

explanation for the export boom there must go beyond the depreciation

of the exchange rate alone. The effects of the depreciation of silver in

Mexico were particularly complex because of the country’s status as a major

international producer and exporter of the metal. Falling silver prices meant

a major deterioration in the barter terms of trade for exports of silver,

approximately half of all Mexican exports. But for other commodities priced

in gold, domestic receipts in silver increased. At the same time, service on

the foreign debt, which had been frequently suspended from 1827 through

1887,rose because of the depreciation of the peso, placing further pressure

on the D

´

ıaz government, which was deeply concerned with access to foreign

capital markets. The issue in Mexico was, therefore, politically divisive, and

the move to the gold standard came in 1905 only after considerable debate

both within and outside the government. Ironically, this carefully managed

transition was to be overturned in the general upheaval that accompanied

the outbreak of the Mexican Revolution in 1910, when convertibility was

suspended.

By and large, then, the great bulk of the scholarly literature sustains the

skepticism that Alec Ford brought to the operation of the gold standard in

Latin America down to World War I. Historians of Argentina, influenced

byahistory of inflation under inconvertible currency, have been the greatest

dissenters, arguing in favor of the stabilizing effects of the gold standard on

prices and production. But a significant body of work contends otherwise,

not only in Latin America but elsewhere. In the European periphery, in

Italy and Spain, stability was more a function of prudent fiscal management

and a healthy balance of payments than it was the result of maintaining

afixedexchange rate and a domestic money supply linked rigidly, even

mechanically, to gold.

After World War I, there was a general return to gold in Latin America,

although resumption of convertibility was generally delayed until well into

the 1920s, as it was in Brazil (1926), Argentina (1927), or Mexico (1927).

Of the countries for which we have adequate studies, only one, Argentina,

resumed convertibility at the prewar parity. When the Great Depression

hit, Argentina and Brazil abandoned the gold standard first, followed by

Mexico. All would undergo significant exchange-rate depreciation after

1930, and by 1933, their currencies had fallen to between 30 and 60 percent

of their gold parities in 1929.AsCarlos D

´

ıaz Alejandro, Jeffrey Sachs, and

Barry Eichengreen have all emphasized, those countries that abandoned

gold most quickly avoided deflation and were able to recover from the

Great Depression expeditiously.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

264 Richard Salvucci

What conclusion can we draw from a review of the literature on mone-

tary regimes in Latin America in this period? The basic lesson, it seems, is

that there were no easy choices, let alone “good” choices to be had, at least

in terms of their macroeconomic implications. As for the gold standard,

Michael Bordo and Barry Eichengreen have concluded that it was “intrin-

sically fragile, prone to confidence problems, and a transmission belt for

policy mistakes.”

6

SOURCES, RATES, AND PATTERNS

OF ECONOMIC GROWTH

In the long run, economic growth depends on increasing aggregate supply.

In the short run, variations in growth are largely the result of changes in

aggregate demand. Aggregate supply, in turn, depends on the availability

of productive factors, labor and capital broadly defined, and the efficiency

with which those factors are used – which is to say, on technology, the

evolution of which is commonly measured by the change in what is termed

total factor productivity. Aggregate demand, in the short run, is affected by

avariety of real and monetary factors, including disturbances in the money

supply, changes in the terms of trade and the outlook of consumers and

investors, and political factors, all of which can be conventionally measured

by the components of aggregate demand.

For our purposes, the developments that had the greatest impact on

aggregate supply were innovations in domestic transportation and immi-

gration. Innovations in domestic transportation of particular interest were

railways, whose impact on potential output were substantial in Argentina,

Brazil, and Mexico, but somewhat less so in Colombia. Immigration mat-

ters because of the expansion of the labor force it implied because natural

rates of population increase were low. Although it is true that innovations

in ocean transportation and transportation technology ultimately made

export expansion possible, their impact on Latin America has been less

well studied. There are also a few subtle points about the role of immigra-

tion in economic growth that must be considered.

John Coatsworth, Sandra Kuntz, Colin Lewis, Rory Miller, Paolo

Riguzzi, and William Summerhill have done the principal work on the

6

Barry Eichengreen and Michael Bordo, “The Rise and Fall of a Barbarous Relic: The Role of Gold

in the International Monetary System,” in Guillermo H. Calvo, Rudiger Dornbusch, and Maurice

Obstfeld, eds., Money, Capital Mobility, and Trade: Essays in Honor of Robert A. Mundell (Cambridge,

MA, 2001), 85.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 265

impact of railroads on the Latin American economies in the nineteenth

century. Coatsworth and Summerhill concluded that the “social savings”

generated by railroads carrying freight and passengers in Argentina, Mex-

ico, and Brazil was substantial, although, inevitably, issues of measurement

pose some challenge. A recent study embodying estimates of social savings

now exists for Colombia as well, although its findings are at a variance with

those of Coatsworth and Summerhill. There has also been some discus-

sion of the importance of railroad development in Bolivia, Chile, Cuba,

Central America, and Peru, although the evidence is less systematic. The

idea behind “social savings” is closely related to that of opportunity cost,

the difference between what resources are earning relative to their next best

use. Hence, the social savings produced by railroads (or any other trans-

portation innovation that economizes on resources) are a measure of the

value of resources freed up from employment in less productive means of

conveyance of people or freight. For our purposes, they are a measure of

the increase in a society’s potential output or income.

Viewed from this perspective, it is difficult to imagine another innovation

whose potential impact on economic growth was greater. The costs of

overland transportation under colonial conditions were notoriously high

and, in the early nineteenth century, were frequently elevated by military

activities that drew heavily on the supply of draft animals. So it was that the

repeated political upheavals experienced after independence magnified the

importance of innovations that reduced the physical costs of domestic trade.

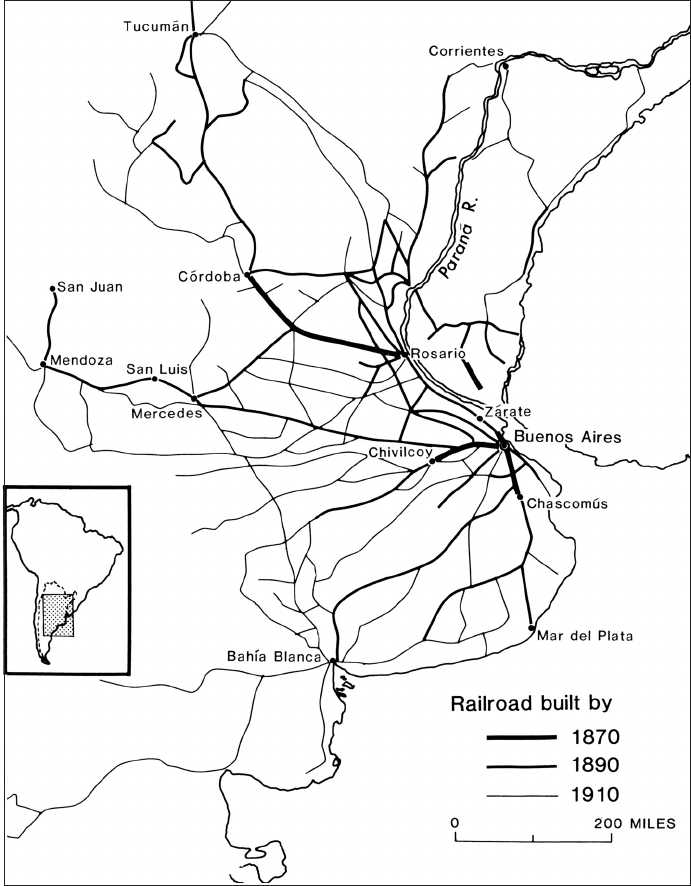

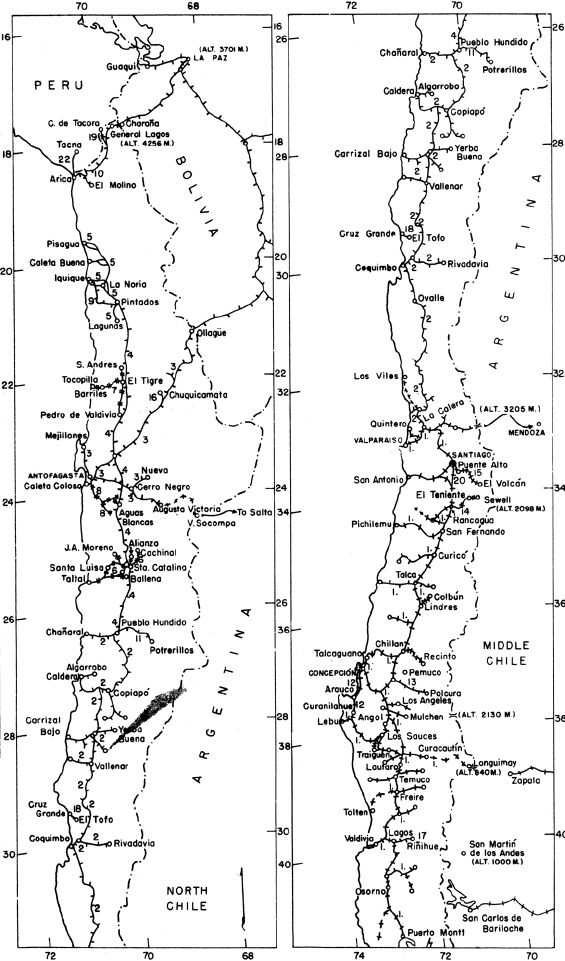

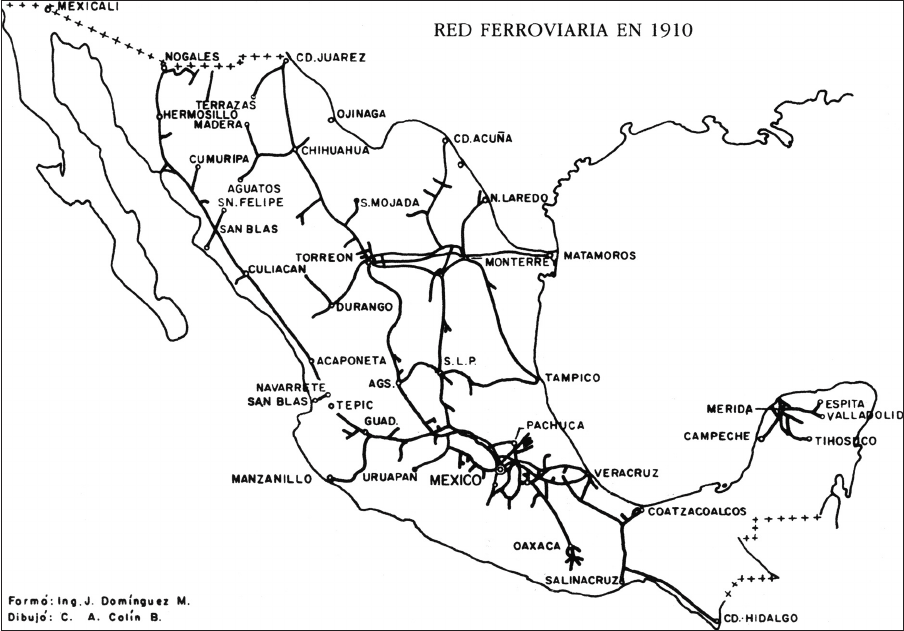

Although the impact of railroads on transportation costs is crucial, there

are other dimensions to the issue as well. The effect of the railroads on

supply was greatest where they formed an integrated network, as they did

in Argentina, Chile, and Mexico, even if, as in Mexico, not all sections

of the country were equally well served. Maps 7.1, 7.2, and 7.3 show the

density of the railroad systems of these three countries. Moreover, it is

clear that the effectiveness of railroad development was not independent of

state activity. Like the gold standard, railroads were a token of modernity

and a symbol of progress and, therefore, highly attractive to the politicians

of the countries in which they operated. Policies designed to integrate

markets and promote regional development had a substantial effect on

economic growth, and when lines ran through populated areas, as they

sometimes did in Mexico, careful government negotiation with popular

interests could be crucial to ensuring successful operation and profitable

results. Theresa van Hoy has analyzed this theme with particular care in

her study of railroad development in southern Mexico, where she speaks

of “authoritarian policies” but “democratic implementations.”

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

266 Richard Salvucci

Map 7.1. Argentine railroads, 1910.

Source: David Rock, Argentina, 1516–1987:FromSpanish Colonization to Alfons

´

ın,revised

and expanded ed., (Berkeley, 1987), 170.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 267

Map 7.2. Chilean railroads, 1942.

Source: U.S. Department of Commerce, Board of Economic Warfare, Geography Division,

“Railways of Chile” (Washington, DC: August 31, 1942).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Map 7.3.M

exican railroads,

1910.

Source:

Sergio Ortiz Hern

´

an, Los ferrocarriles de M

´

exico: Una visi

´

on social y econ

´

omica

(2 vols., Mexico City,

1987), 245.

268

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 269

Railroad development in Latin America began early in Cuba, in 1837, but

it was not, generally speaking, until the latter half of the nineteenth century,

and more specifically, until the 1880s and 1890s, that major expansions in

Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico got underway. Railroad construction began

in Colombia in the 1870s and 1880saswell, but because of political turmoil

and war (1899–1902), many of the roads built were confiscated or destroyed.

For this and other reasons, the railroad boom in Colombia was delayed until

well into the 1920s. In general, the period between 1870 and 1930 witnessed

the greatest expansion of the rail network in the history of Latin America

and much less was constructed thereafter. In 1870, there were roughly 4,000

kilometers of railroads in Latin America. By 1930, the total had reached

117,000 kilometers. In a broad sense, activity in four countries – Argentina,

Brazil, Mexico, and Chile – led the way.

The estimated contributions to potential GDP, the social savings gener-

ated by the railroads, were, by and large, substantial, except in Colombia.

These estimates, provided by Coatsworth, Ram

´

ırez, and Summerhill, are

consistent in that all, other than Colombia, are large by virtually any stan-

dard of measurement. For example, Summerhill calculates that the direct

social savings from railroads in Argentina, based on freight carriage, were

somewhere between 12 and 26 percent of Argentine GDP in 1913,afigure

that sounds surprisingly large in view of Argentina’s largely tractable ter-

rain. But an ample share of Argentine output was transported, which, in

turn, implied that the contribution of railroads would be significant. So,

for instance, by 1890, 84 percent of all wheat and 53 percent of all corn

produced in Argentina was transported by rail. Even as early as 1892,at

a time when the Argentina belle

´

epoque was just beginning, the railroads

produced a social saving of between 6 and 10 percent of GDP, which is still

very substantial. Perhaps more important, Summerhill’s analysis implies

that much of Argentina’s overall productivity growth can be explained by

the expansion of the rail network, suggesting that economies of scale, a

more efficient allocation of resources, and even changes in crop mix as

the acreage devoted to linseed, oats, and barley came to rival that sowed

in corn, if not in wheat (which, in its turn, had revolutionized exports),

were all associated with an increasing density of rail transport. Moreover,

an astonishing increase in commercialization occurred in Argentina under

the stimulus of railroad extension. In the late 1880s, for instance, approxi-

mately two million acres in Argentina were sown in wheat, much of which

was exported. By 1930, the figure had risen to twenty-one million acres.

In Argentina, Summerhill concludes, the contribution of the railroads to

productive potential was as great as immigration’s.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

270 Richard Salvucci

Table 7.4. Some railroad freight social savings estimates

Country (Author) Year

Social savings

(percent GDP)

Argentina (Summerhill) 1913 12–26

Colombia (Ram

´

ırez) 1927 2.25–4.11

Mexico (Coatsworth) 1910 14.9–16.6

Mexico (Summerhill) 1910 8–17

Sources: After Mar

´

ıa Teresa Ram

´

ırez, “Los ferrocarriles y su impacto

sobre la econom

´

ıa colombiana,” Revista de Historia Econ

´

omica 19, 1

(2001); William Summerhill, “Transport Improvements and Eco-

nomic Growth in Brazil and Mexico,” in Stephen Haber, ed.,

How Latin America Fell Behind: Essays on the Economic Histories

of Brazil and Mexico (1800–1914) (Stanford, CA, 1997), 93–117;

and “Profit and Productivity on Argentine Railroads, 1857–1913”

(unpublished).

The results that Coatsworth, Summerhill, Kuntz, and Riguzzi have pro-

duced for Mexico are broadly consistent with the evidence on Argentina. In

terms of sheer size, Coatsworth’s estimate of the social savings for Mexican

railroad was on the order of Summerhill’s for Argentina, but Summerhill

has reduced the Mexican figure somewhat to account for differences in

the assumed responsiveness of demand for freight transport to changes

in relative prices. Summerhill’s figure for Mexico in 1910 (for freight) is

between 8 and 17 percent of GDP – again, a very large number. Because

railroad building in Mexico got off to a very late start, some twenty years

later than in Argentina, this effectively means that its stimulative impact

was largest at the very end of the nineteenth century. Although there is no

question that railroad development was linked to the expansion of exports

(especially in Bolivia, Cuba, Peru, and Central America) and, hence, to a

multiplier effect in terms of total output, there is also considerable evidence

that their impact on purely domestic output was large as well. Sandra Kuntz

has shown that items such as coal, coke, construction materials, firewood,

and maize formed a large, and sometimes overwhelming, proportion of the

physical volumes carried by Mexican rail lines at the end of the nineteenth

century.

The implications of this change were several. On the one hand, opening

the coalfields of northern Mexico to exploitation and transportation facil-

itated the beginnings of heavy industry, if not precisely of a capital-goods

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c07 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:28

Export-Led Industrialization 271

sector linked directly to the railway. On the other hand, the impact on

domestic agricultural productivity, historically quite low, was vital. A care-

ful study by Simon Miller of the regional economy of Quer

´

etaro shows that

the arrival of the railroads there in 1882 opened new markets to hitherto

purely local production; augmented land values; and provided a spur to

mechanization – withal a development perceived in the region as nearly

revolutionary and associated with commercial and financial modernization

tout court.More evidence for this was the increasing presence of corn from

the United States in Mexican markets, some five million bushels between

1883 and 1885 alone. These developments were literally unprecedented and

lend substance to the social savings for Mexico calculated by Coatsworth

and Summerhill. Nor are these results limited to Mexico alone. In his

account of railroad building in the Peruvian central highlands, Rory Miller

finds that railroad construction drove down transportation costs 20 to

30 percent between 1890 and 1930,exercising a major impact on the loca-

tion and productivity of copper mining.

There are, finally, results for Brazilian railroads calculated by Summer-

hill and augmented by Nathaniel Leff. For Brazil, the putative impact

of railroads on both domestic and exportable production was not unlike

what occurred in Argentina and Mexico. In Brazil, too, railroads came

late, the large upswing in their growth occurring first in the 1890s. As in

Mexico, railroads had a dramatic impact on the transportation of domestic

goods, with Leff estimating that, even on Brazil’s “coffee railroads,” the

share of noncoffee freight carried on the eve of the outbreak of World

WarIranged anywhere from 60 to more than 80 percent by volume. In

Brazil, too, this development was at least in part by design because the

structure of railroad rates discriminated in favor of the domestic agricul-

tural sector (foodstuffs, livestock, and timber), which was now linked more

efficiently to urban markets. In some areas, such as the northeast, Leff

estimates that transportation costs fell by 50 percent, with a consequent

impact on relative prices. At the same time, the “coffee lines” experienced

annual increases in coffee shipments on the order of 7 percent per year,

which implies a doubling of shipments in a decade. For this reason, then,

Leff argues that Brazil was now launched on a path of long-term eco-

nomic development. Scholars agree that even though the Brazilian railroad

network was concentrated mostly along the coast and in the southeast

(there was effectively little or no development in the interior), it brought

a larger degree of internal integration to the economy than was hitherto

prevalent.