Bulmer-Thomas V., Coatsworth J., Cortes-Conde R. The Cambridge Economic History of Latin America: Volume 2, The Long Twentieth Century

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

Table 8.1.

Length of railway track in service by country,

1870–1930

Year Argentina Bolivia Brazil Colombia

Costa

Rica Cuba Chile Ecuador Guatemala Honduras

Mexico

1870 732

744 80

1,295 797

417

1880 2,516

3,398 131

1,418 1,777 68

1,074

1890 9,432 238 9,973 282

1,646 2,747 82 190

9,544

1900 16,563 525 15,316 636 282

1,792 4,354 501 567

13,615

1910 27,994 823 21,326 875 654

3,281 5,945 750 662

19,280

1920 33,884 1,597 28,535 1,445 727

3,853 8,211 1,000 741 671 20,800

1930 38,120 1,953 32,478 2,843 669

4,381 8,937 1,132 819 1,109 23,345

Year Nicaragua Panama Paraguay Peru

Puerto

Rico

Dominican

Republic El Salvador Uruguay Venezuela Total

1870

72 669

23

4,065

1880 21

72 1,770

371

10,382

1890 175

217 1,599

127

87 1,133

34,134

1900 225

251 1,790 220 187 105 1,729

851 54,151

1910 235 81 251 1,962 290

233 121 2

,373 879 81,590

1920 257 180 467 2,116 545

236 283 2,668 885 101,463

1930 235 349 497 3,056 545

623 2,746 885 115,786

Note: Length expressed in kilometers.

Source:

Jes

´

us Sanz Fern

´

andez, ed., Historia de Los Ferrocarriles de Iberoam

´

erica, 1837–1995

(Madrid, 1988).

302

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

The Development of Infrastructure 303

0

50,000

100,000

150,000

1870

1876

1882

1888

1894

1900

1906

1912

1918

1924

1930

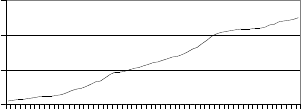

Figure 8.1. Kilometers of railway track in service in Latin America, 1870–1930

Note: Time series is based on continuous series of trackage for five countries (Argentina,

Brazil, Chile, Cuba, and Mexico) and interpolated series for the other countries of the

region.

Source: Jes

´

us Sanz Fern

´

andez, ed., Historia de los ferrocarriles de Iberoam

´

erica, 1837–1995

(Madrid, 1998).

In 1850,few Latin American countries yet possessed a single kilometer of

railway track. Table 8.1 shows that Latin America as a whole still had fewer

than 5,000 kilometers of track by 1870.However, in the ensuing six decades,

the capacity of the sector expanded rapidly. By 1930, 125,000 kilometers of

railways were in operation. Figure 8.1 charts the expansion of track in

service in Latin America from 1870 to 1930.During the 1870s, growth

was weak, though the 1880sbrought a considerable upswing. Growing

political stability, improved financial intermediation, the spillover of savings

from high-income economies abroad, and especially innovations in metals

production (including the introduction of the Bessemer process, which

reduced the cost of steel rails and rolling stock) account for the accelerated

increase in the 1880s.

17

Expansion continued, albeit at a reduced pace, in

the 1890s, slowed in particular by financial crises in Argentina and Brazil,

both of which had accounted for a major share of the overall growth in

Latin American railroad capacity up to that point. A sharp acceleration in

the amount of new track placed in service during the first decade of the

twentieth century stalled with the disruptions of the First World War, and

railway expansion never again attained the earlier pace of growth. Interwar

financial problems were followed by the Great Depression of the 1930s,

while at the same time, motor roads gradually began to offer substitutes for

the railroad for both passenger services and numerous classes of freight.

The geographic distribution of railways across Latin America gener-

ally followed, for much of the period, the imperatives of size, taking into

17

B. R. Mitchell, British Historical Statistics (Cambridge, 1988), 273; U.S. Bureau of the Census,

Historical Statistics of the United States (New York, 1976), 208–9.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

304 William R. Summerhill

account both territory and population, though several exceptions are note-

worthy. Table 8.2 reveals the distribution of railway capacity by country,

with capacity imperfectly indicated by the proportion of all Latin Ameri-

can railway track in service. Unsurprisingly, Argentina, Mexico, Brazil, and

Chile accounted for the vast bulk of the region’s rail capacity. Cuba, with its

early head start, still possessed in 1870 more track in service than anyplace

else in Latin America, though it is no surprise that it did not keep up through

the end of the century and did not maintain its lead. Southern South Amer-

ica quickly emerged to dominate the rest of Latin America in terms of track

per nation. By 1890, Argentina and Brazil together accounted for more than

half of all railways in Latin America. In 1900, these two countries, together

with Mexico, had 75 percent of the region’s track. At the other extreme,

the smaller nations, especially those of Central America, never held more

than a miniscule share of the region’s lines. Yet railway development was

not exclusively a large-country phenomenon. Irrespective of their relative

shares of the region’s total rail capacity, nearly all of the Latin American

countries enjoyed impressive increases in the extension of their respective

railway systems between 1870 and 1930.Table 8.3 presents the trend rates

of the expansion of railway track in service, by country. No pattern can

be readily discerned in the rates of growth. Small and large countries alike

were among the fastest growers in proportional terms. Honduras, starting

of course from a very low base level of track, witnessed a quicker rate of

railway expansion after 1870 than Argentina, Brazil, or Mexico. For most

countries, the rate of increase in railway capacity likely outstripped the rate

of growth of national income, as the railway substituted for preexisting

modes of shipment and simultaneously created income effects that gen-

erated new demands for its own services. Of all the countries listed, only

the Dominican Republic, Peru, and Venezuela stand out as truly laggard

in terms of the expansion of their railway systems. In general terms, the

rapid growth of railways throughout the region is testimony to the broader

process of extensive economic growth underway between 1870 and 1930.

The length of track in service is a simple but useful indicator of capacity,

though alone it does not take into account differences in relative intensity,

either in terms of the population served or in utilization. Here there were

significant differences across Latin America. Additional insights can be

readily gleaned by considering the amount of track in terms of population.

Table 8.4 provides such evidence for 1913,atthe peak of railway growth and

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

Table 8.2.

Share of total Latin American railway track by country (1870–1930)

Year Argentina Brazil Cuba Chile Mexico

Peru Uruguay Bolivia Colombia Venezuela

1870 15.2%

15.4%

26.8% 16.5%

8.6%

13.9%

0.5%

0.0%

1.7%

0.0%

1880 19.9%

26.9%

11.2% 14.1%

8.5%

14.0%

2.9%

0.0%

1.0%

0.0%

1890 25.2%

26.6%

4.4%

7.3% 25.5%

4.3%

3.0%

0.6%

0.8%

0.0%

1900 27.8%

25.7%

3.0%

7.3% 22.9%

3.0%

2.9%

0.9%

1.1%

1.4%

1910 31.8%

24.2% 3.7%

6.8%

21.9%

2.2%

2.7%

0.9%

1.0%

1.0%

1920 31.1%

26.2%

3.5% 7.5%

19.1%

1.9%

2.4%

1.5%

1.3%

0.8%

1930 30.6%

26.0%

3.5% 7.2%

18.7%

2.5%

2.2%

1.6%

2.3%

0.7%

Year Costa Rica Ecuador Guatemala Honduras Nicaragua

Panama Paraguay

Puerto

Rico

Dominican

Republic El Salvador

1870 0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0% 0.0%

0.0%

1.5%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

1880 0.0%

0.5%

0.0%

0.0% 0.2%

0.0%

0.6%

0.0%

0.0%

0.0%

1890 0.0%

0.2%

0.5%

0.0% 0.5%

0.0%

0.6%

0.0%

0.3%

0.2%

1900 0.5%

0.8%

1.0%

0.0% 0.4%

0.0%

0.4%

0.4%

0.3%

0.2%

1910 0.7%

0.9% 0.8%

0.0%

0.3%

0.1%

0.3%

0.3%

0.3%

0.1%

1920 0.7%

0.9% 0.7%

0.6%

0.2%

0.2%

0.4%

0.5%

0.2%

0.3%

1930 0.5%

0.9% 0.7%

0.9%

0.2%

0.3%

0.4%

0.4%

0.0%

0.5%

Source: Sanz Fern

´

andez,

Historia de los ferrocarriles de Iberoam

´

erica, 1837–1995.

305

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

306 William R. Summerhill

Table 8.3. Trend rate of growth of railway track by country,

1870–1930

Country Trend rate of growth (% per year)

Honduras 6.5

Panama 6.5

Ecuador 6.4

Argentina 6.3

Mexico 6.3

Colombia 5.8

Uruguay 5.6

Brazil 5.5

Bolivia 5.4

Puerto Rico 4.7

Chile 3.9

Paraguay 3.9

Costa Rica 3.3

Guatemala 2.6

Cuba 2.5

Nicaragua 2.5

Dominican Republic 1.7

Peru 1

Venezuela 1

Note: In percent per annum. Trend rate of growth calculated by regress-

ing the natural logarithm of track in service against a time trend.

Source: Sanz Fern

´

andez, Historia de los ferrocarriles de Iberoam

´

erica,

1837–1995.

on the eve of the dramatic slowdown of the expansion of railway capacity

throughout Latin America. Argentina had by far the greatest intensity of

capacity in the region, with nearly four kilometers of track for every one

thousand people. Neighboring Uruguay had only half that ratio. The

Argentine ratio of track per capita was actually on par with that of the United

States at the turn of the century. Chile, Brazil, and Mexico register a notch

lower than Argentina but rank high by hemispheric standards. Colombia,

Ecuador, and Panama, despite the late-breaking and impressively rapid

growth rates of their railways, still had, by 1913,very low levels of track

per capita. Panama, with its extensive coastlines and, ultimately, its canal,

was not likely in great need of railway transport, to be sure. But the moun-

tainous inland regions of Colombia and Ecuador would have benefited

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

The Development of Infrastructure 307

Table 8.4. Normalized extension of railways in service in Latin

America, 1913

Country

Track in service

(Km)

Population

(1,000s)

Km of track per

1,000 people

Argentina 31,186 7,917 3.94

Chile 8,147 3,509 2.32

Uruguay 2,592 1,316 1.97

Costa Rica 619 387 1.60

Cuba 3,846 2,507 1.53

Mexico 20,447 14,855 1.38

Brazil 26,062 24,161 1.08

Guatemala 987 1,180 0.84

Peru 3,317 4,347 0.76

Bolivia 1,440 2,025 0.71

Paraguay 373 657 0.57

Nicaragua 322 581 0.55

Honduras 241 588 0.41

Ecuador 587 1,469 0.40

Venezuela 858 2,633 0.33

El Salvador 328 1,058 0.31

Colombia 1,166 5,318 0.22

Panama 76 378 0.20

Source: Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of Latin America Since

Independence (Cambridge, 1994)

considerably from higher levels of railway services. Similar variation appears

across the larger Latin American economies when rough measures of capac-

ity utilization are taken into consideration for the countries in which such

information is available. Reliable measures of railway output are not yet

available for all of the countries, preventing a systematic comparison of

rates of utilization. Argentina was by far the most railway-intensive of the

Latin American economies, exhibiting far greater density of freight service

per kilometer of track in 1913 than any other case for which freight-density

measures are available. The level of freight service per capita in Argentina

was staggering by regional standards, more than seven times that for Brazil

and nearly three times that for Mexico.

18

18

William R. Summerhill, “Economic Consequences of Argentine Railroad Development” (mimeo-

graph, 2000).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

308 William R. Summerhill

FINANCING RAILWAYS

Finance proved to be a serious hurdle for all infrastructure investments in

the nineteenth century. In spite of the overwhelming advantages in most

regions offered by railways, so obvious to many contemporary observers,

the curious fact is that the new technology was adopted relatively late in

most of Latin America. Little of this tardiness was attributable to a shortage

of earnings from exports. Because the capital equipment, and even techni-

cal expertise, required for railway construction and operation came from

abroad, it is a tautology that export earnings necessarily were required to pay

for railways. Thus, the possibility of creating infrastructure with a foreign

technology necessarily hinged, in an aggregate accounting sense, on the abil-

ity to successfully establish export activities. As Bulmer-Thomas has aptly

noted, the fate of individual Latin American countries in the nineteenth-

century commodity lottery could matter deeply.

19

Yet export earnings were

available in most Latin American countries, even in the 1840s, in amounts

large enough to begin to create some railways, although railways were not

built outside of colonial Cuba. Although export earnings were necessary to

import the capital goods needed for railways, their existence proved in no

way a sufficient condition for the finance of infrastructure. Other factors

were more important in attracting railway investment, and the abilities of

individual nations to tap domestic and foreign savings for infrastructure

varied considerably in this regard. Much of Spanish America had defaulted

on sovereign debt after independence, complicating dramatically the abil-

ity of government to secure funds for internal improvements.

20

Inaregion

with badly underdeveloped capital markets, the resources to finance huge

investments required for the construction of railways were few and far

between. With their high fixed costs and uncertain future profits, railways

required large initial outlays, and a large dose of investor confidence, to

construct and operate. In countries lacking the financial institutions capa-

ble of mobilizing a large volume of private savings and converting them

into loanable funds, financing railway construction proved to be a major

obstacle to infrastructural development. Indeed, the early railway history

of Latin America is marked by government railway concessions that never

19

Victor Bulmer-Thomas, The Economic History of Latin America Since Independence, 2nd ed.

(Cambridge, 2003).

20

Carlos Marichal, ACentury of Debt Crisis in Latin America (Princeton, NJ, 1989).

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

The Development of Infrastructure 309

bore fruit.

21

Capital drawn from a variety of domestic sources, including

governments, helped finance the construction of the earliest lines. In light

of the institutional constraints on the domestic financial intermediation

and low savings rates, the countries of the region soon turned to the far more

advanced capital markets of the industrializing North Atlantic economies.

These they tapped for funds that were not forthcoming domestically. Given

the great uncertainty over the profits to be generated by the railways, cen-

tral and provincial governments in Argentina, Mexico, and Brazil offered

investors blandishments in the form of subsidies and profit guarantees to

attract railway investors. The various financial arrangements employed in

constructing the early railway systems meant that, by the turn of the cen-

tury, countries had railway sectors that combined multiple mechanisms of

finance, drawing funds from the personal savings of single owners, local

stock and bond issues, foreign stock and bond issues, and state coffers. In

most countries, the single largest source of initial investment in infrastruc-

ture was the overseas capital markets.

22

In Mexico, some early regional lines were financed by local entrepreneurs

using sundry mechanisms to raise funds, including a lottery in one case.

However, it was U.S. firms that ultimately garnered concessions to build

the major trunk lines of the country in the late nineteenth century, and

U.S. investors ultimately financed much of Mexico’s railway construction.

“Mexicanization” of the nation’s railways by the government after the turn

of the century also drew on foreign capital markets to raise loans, enabling

the government to buy controlling shares of the major lines and better

control rates and service.

23

In Argentina and Brazil, the early lines were

similarly built using funds drawn from local and foreign markets, but also

relied heavily on government involvement. Brazil’s second railway, the Dom

Pedro II, bogged down financially in its first decade of operation. The Brazil-

ian government interceded, buying out the shareholders and becoming the

21

Coatsworth, Growth Against Development, 33–8.For Brazil, one need only compare the list of hun-

dreds of concessions granted as of the early 1890s with the much smaller number of lines actually

in operation in the early twentieth century; Jo

˜

ao Chrockatt Pereira de Castro, Brazilian Railways:

Their History, Legislation, and Development (Rio de Janeiro, 1893), and Brazil, Minist

´

erio da Viac¸

˜

ao

eObras P

´

ublicas, Inspectoria Federal das Estradas, Estat

´

ıstica das Estradas de Ferro da Uni

˜

ao Relativo

ao Anno 1898 (Rio de Janeiro, 1899).

22

The role of the British capital market in Latin America is addressed in Lance E. Davis and Robert

A. Huttenback, Mammon and the Pursuit of Empire (Cambridge, 1988); Michael Edelstein, Overseas

Investment in the Age of High Imperialism: The United Kingdom 1850–1914 (New York, 1982); and

Irving Stone, The Composition and Distribution of British Investment in Latin America, 1865 to 1913

(New York, 1987).

23

Coatsworth, Growth Against Development, 37–8, 44–6.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

310 William R. Summerhill

sole owner of the line, which it thereafter extended, ultimately making

it the largest and most important railway in the country.

24

An ensuing

wave of railway construction, built in the late 1850s and the 1860sinthe

northeast and in S

˜

ao Paulo, was undertaken by British companies, financed

initially by stock issues, and later by bonds, in London.

25

Brazilians also

financed railways through local stock and bond issues, as was the case of

the Companhia Paulista and the Companhia Mogiana in S

˜

ao Paulo, and

the early phase of the Leopoldina, in Minas Gerais. In all of these cases,

local funds could not alone sustain additional investment, and to finance

expansion, Brazilian-owned lines regularly turned to London to obtain

loans.

26

Argentina financed its early lines with local private funds, govern-

ment construction, and British capital that enjoyed dividend guarantees,

though here the pattern involved a reversal of the Brazilian and Mexican

experiences near the end of the century. In the wake of the Baring Crisis in

the 1890s, some of the government-owned lines were actually turned over

to private hands.

27

Governments sought to satisfy regional interests by adopting a liberal

concession scheme. In Mexico, the central government passed concessions

down to state governments, whereas in Brazil, provinces could concede

routes within their borders but the central government granted conces-

sions to both intra- and interprovincial lines. Railroad routing and loca-

tion in Latin America were sometimes a function of economic prospects but

were also heavily influenced by the political and financial strength of local

interests. Fazendeiros, estancieros, and hacendados seeking to add to their

wealth lobbied to ensure that a railway would pass near their properties in

order to raise the value of their land. The fact that all landowners desired

access to the cheapest transport possible meant that disputes over the trace

of proposed rail line were frequent, at times slowing construction.

28

The

result for each country was a rail system whose layout was closely tied to

extant areas of settlement and within regions where immediate prospects for

24

Almir Chaiban El-Kareh, Filha branca de m

˜

ae preta: A Companhia da Estrada de Ferro D. Pedro II,

1855–1865 (Petr

´

opolis, 1982), 117–28.

25

Richard Graham, Britain and the Onset of Modernization in Brazil (Cambridge, 1968), 51–72.

26

Fl

´

avio Azevedo Marques de Saes, As ferrovias de S

˜

ao Paulo, 1870–1940 (S

˜

ao Paulo, 1981), 165–7; Colin

M. Lewis, Public Policy and Private Initiative: Railway Building in S

˜

ao Paulo, 1860–1889 (London,

1991), 35–51.

27

Colin M. Lewis, British Railways in Argentina, 1857–1914 (London, 1983), 124–45.

28

Competing traces of the Companhia Paulista in S

˜

ao Paulo, for example, were disputed by various

parties; see Robert Mattoon, “The Companhia Paulista de Estradas de Ferro, 1868–1900: Local

Railway Enterprise in S

˜

ao Paulo, Brazil” (Ph.D. dissertation, Yale University, 1972), 50–60.

Cambridge Histories Online © Cambridge University Press, 2008

P1: GDZ

0521812909c08 CB929-Bulmer 0 521 81290 9 October 6, 2005 12:32

The Development of Infrastructure 311

commercial profit (though not necessarily the profitability of the railways)

were considerable. Mexico possessed a well-integrated rail grid by 1910,

linking the major population centers to the coasts and to the United States.

Argentine rail lines fanned out from Buenos Aires, with an impressive

degree of cross-cutting articulation by 1900.Bythe turn of the century,

Brazil had two large regional concentrations of connected railways: one in

the northeast, which tied the interior to major ports, and a separate network

linking the cities, farming areas, and ports of the south and south center.

Latin American societies and economies were predominantly rural for

much of the period, and landowners played a central role in shaping the

course of public transport policies. In particular, landowners lobbied gov-

ernment to reduce railway freight charges. By way of comparison, in the

United States, agrarian populists complaining about rail rates had to await

relief from state-level regulation and the passage of the Interstate Com-

merce Act in 1887.Most Latin Americans had recourse to central govern-

ment intervention in rate-setting from the outset. Although much of Latin

America was made up of high-tariff countries, to further boost construc-

tion railway equipment was typically imported at reduced rates or altogether

duty-free. The policies regarding concessions, guarantees, and subsidy were

one reason that despite their late start, Latin American rail systems grew

at a relatively fast rate. Indeed, without such preferential policies, the pace

at which cheap transport services diffused through the countryside would

have been far slower.

Accompanying the deceleration of railway construction after 1914 was a

reduced supply of investible funds from abroad.

29

Domestic capital mar-

kets in Latin America, which had developed considerably since the 1870s,

remained too small, and savings rates too low, to carry alone the burden

of finance going forward from the Great War.

30

Demands for capital, not

exclusive to infrastructure, remained high after 1914, but the supply condi-

tions were altered dramatically. As finance stagnated, so did the expansion

of Latin American rail systems.

Tr eating capital, whether foreign or domestic in origin, as a single factor,

even in infrastructure, is a far too general formulation to provide satisfactory

29

See the contribution by Alan Taylor in this volume.

30

On the financial disruptions in Brazil generally, see Winston Fritsch, External Constraints on Economic

Policy in Brazil (Pittsburgh, PA, 1988); for Argentina, see Gerardo della Paolera and Alan M. Taylor,

Straining at the Anchor: The Argentine Currency Board and the Search for Macroeconomic Stability, 1880–

1935 (Chicago, 2001). In Mexico, this coincided with the most violent and financially disruptive phase

of the Revolution; see Stephen Haber et al., The Politics of Property Rights (Cambridge, 2003), 80–123.