Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

30. Short−Term Financial

Planning

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

878 PART IX Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

11. Do you think you could make money by setting up a firm which would (a) issue com-

mercial paper and (b) relend money to businesses at a rate slightly higher than the com-

mercial paper rate but still less than the rate charged by banks?

12. Use the Market Insight database (www

.mhhe.com/edumarketinsight

) to find recent

balance sheets and income statements for two companies. Draw up a sources and uses

of cash statement and a sources and uses of funds statement as in Tables 30.4 and 30.6.

13. Use the Market Insight database (www

.mhhe.com/edumarketinsight

) to compare the

investment in current assets of different companies. Which of these companies make a

heavy investment in inventories or receivables? Can you explain why?

14. The Federal Reserve Bulletin publishes the results of a quarterly survey of bank lend-

ing (see www

.federalreserve.gov/releases/E2/

). Use the latest survey to describe the

pattern of bank lending by domestic banks. Examine, for example, whether most loans

are secured and whether they are made under commitment. What are the different

characteristics of small and large loans? Now compare the results of this survey with

an earlier one. Have there been any important changes?

CHALLENGE

QUESTIONS

1. In some countries the market for long-term corporate debt is limited, and firms turn to

short-term bank loans to finance long-term investments in plant and machinery. When

a short-term loan comes due, it is replaced by another one, so that the firm is always a

short-term debtor. What are the advantages and disadvantages?

2. Axle Chemical Corporation’s treasurer has forecasted a $1 million cash deficit for the

next quarter. However, there is only a 50 percent chance this deficit will actually occur.

The treasurer estimates that there is a 20 percent probability the company will have no

deficit at all and a 30 percent probability that it will actually need $2 million in short-

term financing. The company can either take out a 90-day unsecured loan for $2 million

at 1 percent per month or establish a line of credit, costing 1 percent per month on the

amount borrowed plus a commitment fee of $20,000. If excess cash can be reinvested at

9 percent, which source of financing gives the lower expected cost?

3. Term loans usually require firms to pay a fluctuating interest rate. For example, the in-

terest rate may be set at “1 percent above prime.” The prime rate sometimes varies by

several percentage points within a single year. Suppose that your firm has decided to

borrow $40 million for five years. It has three alternatives. It can (a) borrow from a bank

at the prime rate, currently 10 percent. The proposed loan agreement requires no prin-

cipal repayments until the loan matures in five years. It can (b) issue 26-week commer-

cial paper, currently yielding 9 percent. Since funds are required for five years, the com-

mercial paper will have to be rolled over semiannually. That is, financing the $40

million requirement for five years will require 10 successive commercial paper sales.

Or, finally, it can (c) borrow from an insurance company at a fixed rate of 11 percent. As

in the bank loan, no principal has to be repaid until the end of the five-year period.

What factors would you consider in analyzing these alternatives? Under what circum-

stances would you choose (a)? Under what circumstances would you choose (b) or (c)?

(Hint: Don’t forget Chapter 24.)

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER THIRTY-ONE

880

CASH MANAGEMENT

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 30 PROVIDED an overall idea of what is involved in short-term financial management. Now it

is time to get down to detail. We begin in this chapter by looking at how companies manage their

holdings of cash and marketable securities. Then in the next chapter we look at the terms on which

firms sell their goods and how they ensure that their customers pay promptly.

Out first task is to explain how cash is collected and paid out. In the United States small routine

payments are commonly made by check. You want to ensure that when customers pay by check, you

can convert these payments into usable cash in the bank quickly and cheaply. The use of checks is on

the decline and large payments are almost always made electronically. You therefore need to under-

stand how electronic payment systems work.

Our second task is to consider how much cash the firm should hold. Companies have a choice be-

tween holding cash in the bank and investing it in short-term securities. There is a trade-off here. Cash

gives you a store of liquidity, which can be used to pay employees and suppliers. However, cash has

the disadvantage that it does not pay interest. As we explain in the second section of this chapter,

the trick is to strike a sensible balance.

In the last chapter we explained how companies raise short-term loans to tide them over a tem-

porary cash shortage. If you are in the opposite position and have surplus cash, you need to know

where you can park it to earn interest. So in the final section of this chapter we look at the menu of

short-term investments that are available to the financial manager.

881

31.1 CASH COLLECTION AND DISBURSEMENT

The majority of small face-to-face purchases are made with coins or dollar bills.

The most popular alternative in the United States for retail purchases is to pay by

check. Each year individuals and firms write about 70 billion checks.

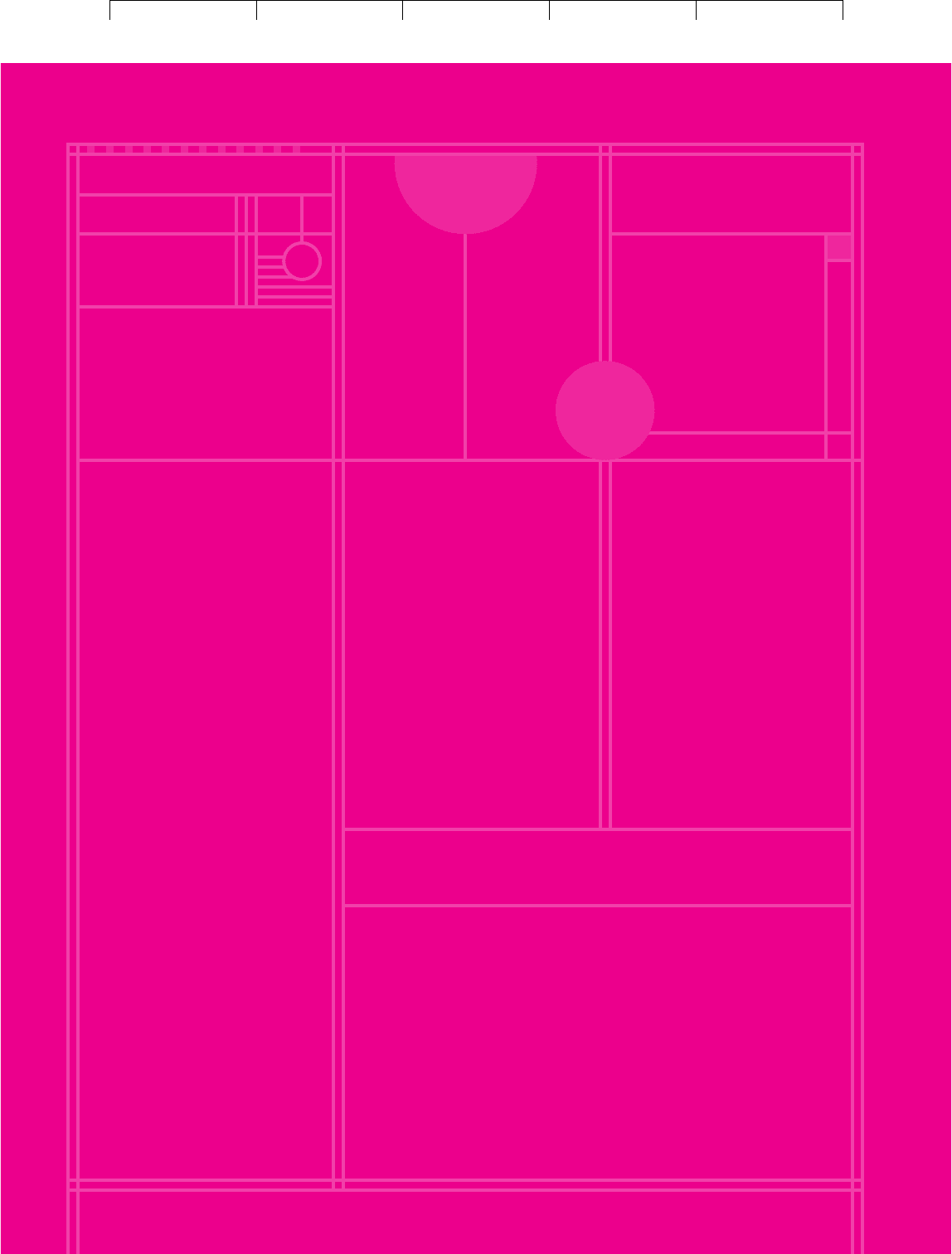

Notice that the United States is unusual in this heavy use of checks. For exam-

ple, Figure 31.1 compares retail payment methods in the United States and Hol-

land. You can see that checks are almost unknown in Holland: Most payments

there are made by debit cards, direct debit, or credit transfer.

1

How Checks Create Float

How does the firm’s cash balance change when it writes or deposits a check? Suppose

that the United Carbon Company has $1 million on demand deposit with its bank. It

now pays one of its suppliers by writing and mailing a check for $200,000. The com-

pany’s ledgers are immediately adjusted to show a cash balance of $800,000. But the

company’s bank won’t learn anything about this check until it has been received by

the supplier, deposited at the supplier’s bank, and finally presented to United Car-

bon’s bank for payment.

2

During this time United Carbon’s bank continues to show

1

Debit cards allow the cardholder to transfer money directly to the receiver’s bank account. With a

credit transfer the payer initiates the transaction, for example by giving her bank a standing order to

make a regular payment. With a direct debit the transaction is initiated by the payee and is usually

processed electronically.

2

Checks deposited with a bank are cleared through the Federal Reserve clearing system, through a cor-

respondent bank, or through a clearinghouse of local banks.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

in its ledger that the company has a balance of $1 million. The company obtains the

benefit of an extra $200,000 in the bank while the check is clearing. This sum is often

called payment, or disbursement float.

882 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

Check

Direct debit

Debit card

Credit card

Credit transfer

2%

19%

4%

1%

74%

52%

0%

18%

27%

3%

Check

Direct debit

Debit card

Credit card

Credit transfer

USA Holland

FIGURE 31.1

Shares of noncash retail payments in the USA and Holland in 1997. Notice the heavy use of checks in the USA.

Source: “Retail Payments in Selected Countries: A Comparative Study,” Bank for International Settlements, Basel, 1999.

Company's ledger balance

$800,000

+

Bank's ledger balance

$1,000,000

equals

Payment float

$200,000

Float sounds like a marvelous invention, but unfortunately it can also work in

reverse. Suppose that in addition to paying its supplier, United Carbon receives a

check for $100,000 from a customer. It deposits the check, and both the company

and the bank increase the ledger balance by $100,000:

Company's ledger balance

$900,000

+

Bank's ledger balance

$1,100,000

equals

Payment float

$200,000

But this money isn’t available to the company immediately. The bank doesn’t ac-

tually have the money in hand until it has sent the check to, and received pay-

ment from, the customer’s bank. Since the bank has to wait, it makes United Car-

bon wait too—usually one or two business days. In the meantime, the bank will

show that United Carbon has an available balance of $1 million and an availability

float of $100,000:

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Notice that the company gains as a result of the payment float and loses as a re-

sult of the availability float. The difference is often termed the net float. In our ex-

ample, the net float is $100,000. The company’s available balance is therefore

$100,000 greater than the balance shown in its ledger.

As financial manager you are concerned with the available balance, not with the

company’s ledger balance. If you know that it is going to be a week or two before

some of your checks are presented for payment, you may be able to get by on a

smaller cash balance. This game is often called playing the float.

You can increase your available cash balance by increasing your net float. This

means that you want to ensure that checks paid in by customers are cleared rap-

idly and those paid to suppliers are cleared slowly. Perhaps this may sound like

rather small beer, but think what it can mean to a company like Ford. Ford’s daily

sales average about $450 million. Therefore if it can speed up the collection process

by one day, it frees $450 million, which is available for investment or payment to

Ford’s stockholders.

Some financial managers have become overenthusiastic in managing the float.

In 1985, the brokerage firm E. F. Hutton pleaded guilty to 2,000 separate counts of

mail and wire fraud. Hutton admitted that it had created nearly $1 billion of float

by shuffling funds between its branches, and through various accounts at different

banks. These activities cost the company a $2 million fine and its agreement to re-

pay the banks any losses they may have incurred.

Managing Float

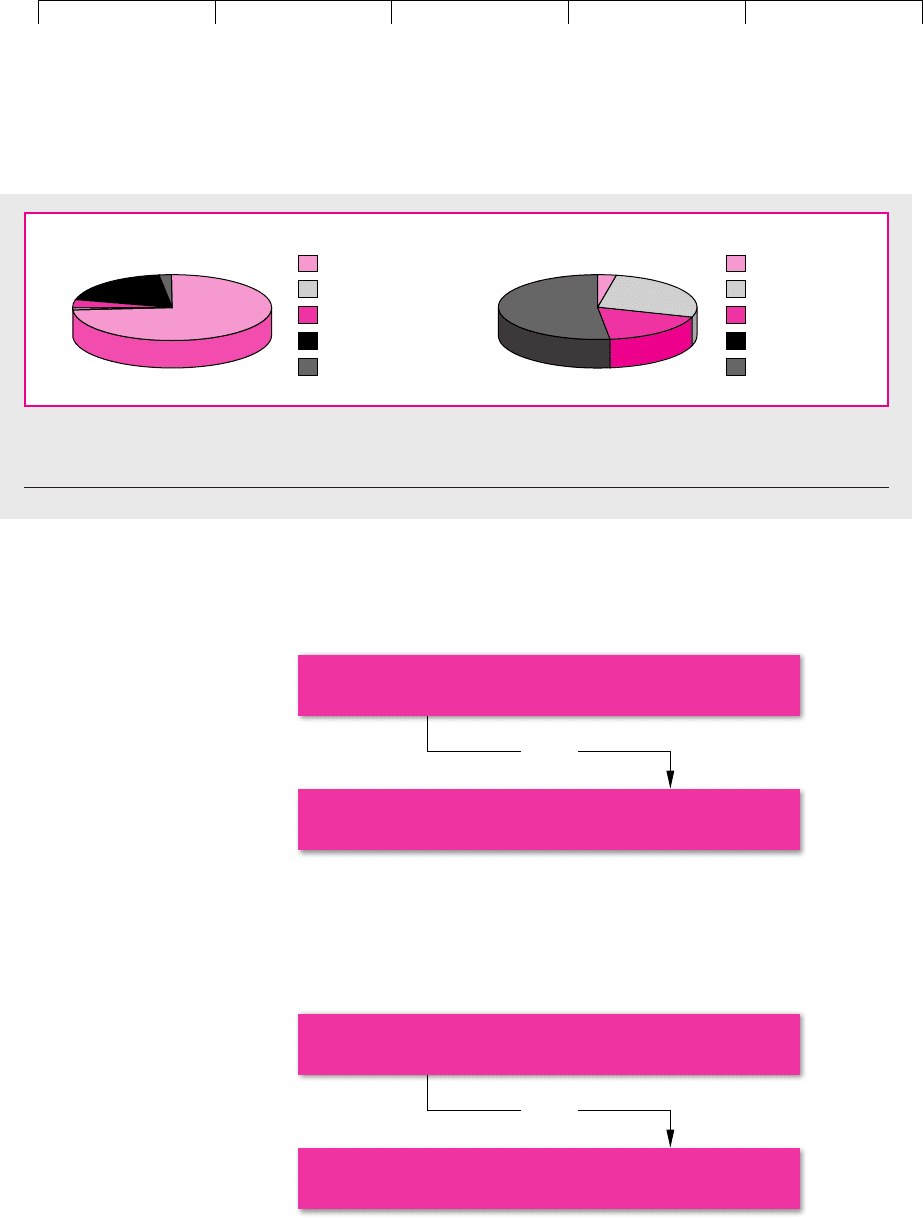

Float is the child of delay. Actually there are several kinds of delay, and so people in

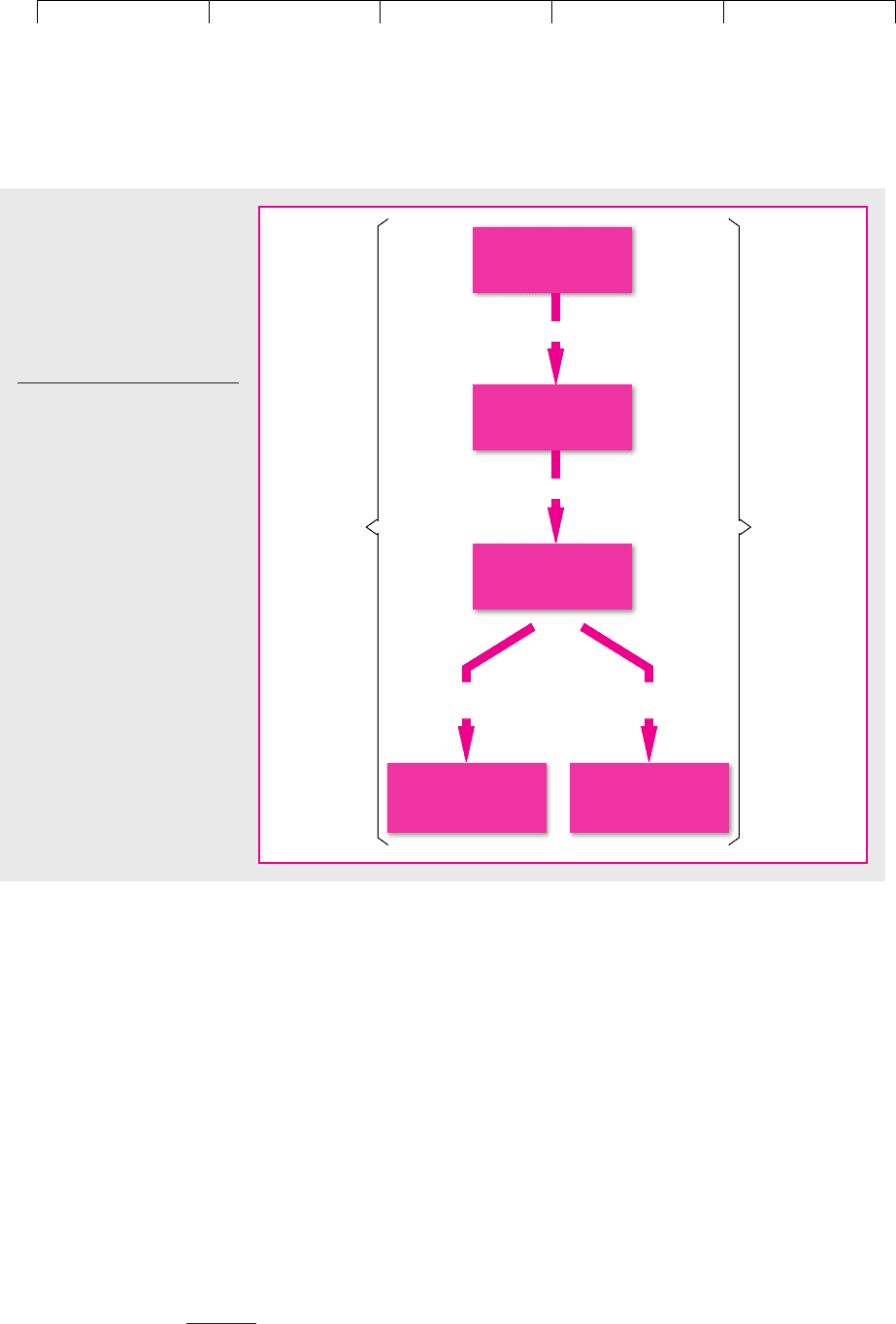

the cash management business refer to several kinds of float. Figure 31.2 summarizes.

Of course the delays that help the payer hurt the recipient. Recipients try to

speed up collections. Payers try to slow down disbursements.

Speeding Up Collections

Many companies use concentration banking to speed up collections. In this case

customers in a particular area make payment to a local branch office rather than

to company headquarters. The local branch office then deposits the checks into a

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 883

Company's ledger balance

$900,000

+

Bank's ledger balance

$1,100,000

equals

Payment float

$200,000

Available balance

$1,000,000

+

Availability float

$100,000

equals

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

local bank account. Surplus funds are transferred to a concentration account at one

of the company’s principal banks.

Concentration banking reduces float in two ways. First, because the branch office

is nearer to the customer, mailing time is reduced. Second, since the customer’s check

is likely to be drawn on a local bank, the time taken to clear the check is also reduced.

Concentration banking brings many small balances together in one large, central bal-

ance, which can then be invested in interest-paying assets through a single transaction.

For example, when Amoco streamlined its U.S. bank accounts in 1995, it was able to

reduce its daily bank balances in non-interest-bearing accounts by almost 80 percent.

3

Often concentration banking is combined with a lock-box system. In a lock-box

system, you pay the local bank to take on the administrative chores. The system

works as follows. The company rents a locked post office box in each principal re-

gion. All customers within a region are instructed to send their payments to the

post office box. The local bank, as agent for the company, empties the box at regu-

lar intervals and deposits the checks in the company’s local account. Surplus funds

are transferred periodically to one of the company’s principal banks.

884 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

Payer sees

same delays

as payment

float

Recipient

sees delays

as collection

float

Check received

Check deposited

Check

charged to

payer's account

Cash

available

to recipient

Check mailed

Processing float

Presentation

float

Availability

float

Mail float

FIGURE 31.2

Delays create float. Each heavy

arrow represents a source of

delay. Recipients try to reduce

delay to get available cash

sooner. Payers prefer delay

because they can use their

cash longer.

Note: The delays causing avail-

ability float and presentation float

are equal on average but can differ

from case to case.

3

“Amoco Streamlines Treasury Operations,” The Citibank Globe, November/December 1998.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

How many collection points do you need if you use a lock-box system or con-

centration banking? The answer depends on where your customers are and on the

speed of the U.S. mail. For example, suppose that you are thinking of opening a

lock box. The local bank shows you a map of mail delivery times. From that and

knowledge of your customers’ locations, you come up with the following data:

• Average number of daily payments to lock box: 150

• Average size of payment: $1,200

• Rate of interest per day: .02 percent

• Saving in mailing time: 1.2 days

• Saving in processing time: .8 day

On this basis, the lock box would increase your collected balance by

150 items per day ⫻ $1,200 per item ⫻ (1.2 ⫹ .8) days saved ⫽ $360,000

Invested at .02 percent per day, $360,000 gives a daily return of

.0002 ⫻ $360,000 ⫽ $72

The bank’s charge for operating the lock-box system depends on the number of

checks processed. Suppose that the bank charges $.26 per check. That works out to

150 ⫻ .26 ⫽ $39 per day. You are ahead by $72 ⫺ 39 ⫽ $33 per day, plus whatever

your firm saves from not having to process the checks itself.

Our example assumes that the company has only two choices. It can do nothing,

or it can operate the lock box. But maybe there is some other lock-box location, or

some mixture of locations, that would be still more effective. Of course, you can al-

ways find this out by working through all possible combinations, but it may be

simpler to solve the problem by linear programming. Many banks offer linear pro-

gramming models to solve the problem of locating lock boxes.

4

Controlling Disbursements

Speeding up collections is not the only way to increase the net float. You can also

do so by slowing down disbursements. One tempting strategy is to increase mail

time. For example, United Carbon could pay its New York suppliers with checks

mailed from Nome, Alaska, and its Los Angeles suppliers with checks mailed from

Vienna, Maine.

But on second thought you will realize that such post office tricks are unlikely

to give more than a short-run payoff. Suppose you have promised to pay a New

York supplier on February 29. Does it matter whether you mail the check from

Alaska on the 26th or from New York on the 28th? Of course, you could use a re-

mote mailing address as an excuse for paying late, but that’s a trick easily seen

through. If you have to pay late, you may as well mail late.

5

There are effective ways of increasing presentation float, however. For example,

suppose that United Carbon pays its suppliers with checks written on a New York

City bank. From the time that the check has been deposited by the supplier, there

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 885

4

See, for example, A. Kraus, C. Janssen, and A. McAdams, “The Lock-Box Location Problem,” Journal of

Bank Research 1 (Autumn 1970), pp. 50–58.

5

Since the tax authorities look at the date of the postmark rather than the date of receipt, companies have

been tempted to use a remote mailing address to pay their tax bills. But the tax authorities have reacted

by demanding that large tax bills be paid by electronic transfer.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

will be an average lapse of little more than a day before it is presented to United

Carbon’s bank for payment. The alternative is that United Carbon pays its suppli-

ers with checks mailed to arrive on time but written on a bank in Helena, Montana;

Midland, Texas; or Wilmington, Delaware. In these cases, it may take three or four

days before each check is presented for payment. United Carbon, therefore, gains

several days of additional float.

6

Some firms even maintain disbursement accounts in different parts of the coun-

try. The computer looks up each supplier’s zip code and automatically produces a

check on the most distant bank.

The suppliers won’t object to these machinations because the Federal Reserve

guarantees a maximum clearing time of two days on all checks cleared through its

system. The Federal Reserve, however, does object and has been trying to prevent

remote disbursement.

A New York City bank receives several check deliveries each day from the Fed-

eral Reserve system as well as checks that come directly from other banks or

through the local clearinghouse. Thus, if United Carbon uses a New York City bank

for paying its suppliers, it will not know at the beginning of the day how many

checks will be presented for payment. It must either keep a large cash balance

to cover contingencies or be prepared to borrow. However, instead of having a

disbursement account with a bank in New York, United Carbon could open a zero-

balance account with a regional bank that receives almost all check deliveries in the

form of a single, early-morning delivery from the Federal Reserve. Therefore, it can

let the cash manager at United Carbon know early in the day exactly how much

money will be paid out that day. The cash manager then arranges for this sum to

be transferred from the company’s concentration account to the disbursement ac-

count. Thus by the end of the day (and at the start of the next day), United Carbon

has a zero balance in the disbursement account.

United Carbon’s regional bank account has two advantages. First, by choosing

a remote location, the company has gained several days of float. Second, because

the bank can forecast early in the day how much money will be paid out, United

Carbon does not need to keep extra cash in the account to cover contingencies.

The Finance in the News box describes how one Canadian company was able

to reduce its cash needs by concentrating its cash holdings and using zero-

balance accounts.

Electronic Funds Transfer

Throughout the world the use of checks is on the decline. For consumers they are

being replaced by credit or debit cards. In the case of companies, payments are in-

creasingly made electronically.

7

Electronic payments are relatively few in number

but they account for the majority of transactions by value. Electronic payment sys-

tems may be of two kinds—a gross settlement system or a net settlement system.

With gross settlement each payment is settled individually; with net settlement all

payment instructions are accumulated and then at the end of the day any imbal-

ances are settled.

886 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

6

Remote disbursement accounts are described in I. Ross, “The Race Is to the Slow Payer,” Fortune, April

18, 1983, pp. 75–80.

7

Consumers also may receive and pay bills electronically via their personal computer. Currently Elec-

tronic Bill Presentment and Payment (EBPP) accounts for only a small proportion of payments but it is

forecasted to grow rapidly.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

In the United States there are two systems for making large-value electronic

payments—Fedwire (a gross system) and CHIPS (a net system). Fedwire is op-

erated by the Federal Reserve system and connects over 10,000 financial institu-

tions in the United States to the Fed and thereby to each other. Suppose Bank A

instructs the Fed to transfer $1 million from its account with the Fed to the ac-

count of Bank B. Bank A’s account is debited immediately and Bank B’s account

is credited at the same time. Fedwire is therefore an example of a real-time gross

settlement (RTGS) system. Most developed countries now operate RTGS systems

for large-value payments.

Real-time gross settlement suffers from a potential problem. If Bank A needs to

pay Bank B, B needs to pay C, and C needs to pay A, there is a risk that the system

could gridlock unless each bank kept a large reserve with the Fed. (A might not be

able to pay B until it has been paid by C, C can’t pay A until paid by B, and B in

turn is awaiting payment by A.) To oil the wheels, therefore, the Fed takes on the

credit risk by paying the receiving bank even if there are insufficient funds in the

account of the payer. Since each payment is final and guaranteed by the Fed, each

receiving bank can be sure that it has the money and can give its customer imme-

diate access to the funds.

Cross-border high-value payments in dollars are handled by CHIPS, which is a

privately owned system connecting 115 large domestic and foreign banks. CHIPS

accumulates payment instructions throughout the day, and at the end of the day

each bank settles up the net payment using Fedwire. This means that, if the bank

receiving payments makes the funds available to its customers during the day, it

would be at risk if the paying bank goes belly up during the day. Banks control this

risk by imposing intraday credit limits on their exposure to each other.

887

FINANCE IN THE NEWS

HOW LAIDLAW RESTRUCTURED

ITS CASH MANAGEMENT

The Canadian company, Laidlaw Inc., has more

than 4,000 facilities throughout America, operating

school bus services, ambulance services, and Grey-

hound coaches. During the 1990s the company ex-

panded rapidly through acquisition, and its number

of banking relationships multiplied until it had

1,000 separate bank accounts with more than 200

different banks. The head office had no way of

knowing how much cash was stashed away in these

accounts until the end of each quarter, when it was

able to construct a consolidated balance sheet.

To economize on the use of cash, Laidlaw’s fi-

nancial manager sought to cut the company’s aver-

age float from five days to two. At the same time

management decided to consolidate cash manage-

ment at five key banks. This enabled cash to be

zero-balanced to a single account for each division

and swept daily to Laidlaw’s disbursement bank.

Because the head office could obtain daily reports

of the company’s cash position, cash forecasting

was improved and the company could reduce its

cash needs still further.

Source: Cash management at Laidlaw is described in G. Mann and

S. Hutchison, “Driving Down Working Capital: Laidlaw’s Story,”

Canadian Treasurer Magazine, August/September 1999.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Fedwire and CHIPS provide same-day settlement and are used to make high-

value payments. Bulk payments such as wages, dividends, and payments to sup-

pliers generally travel through the Automated Clearinghouse (ACH) system and take

two to three days. In this case the company simply needs to provide a computer

file of instructions to its bank, which then debits the corporation’s account and for-

wards the payments to the ACH system. The ACH system is the largest payment

system in the United States and in 1999 handled 6.2 billion payments with a value

of $19 trillion.

For companies that are “wired” to their banks, customers, and suppliers, these

electronic payment systems have at least three advantages:

• Record keeping and routine transactions are easy to automate when money

moves electronically. Campbell Soup’s Treasury Management Department

discovered that it could handle cash management, short-term borrowing and

lending, and bank relationships with a total staff of seven. The company’s

domestic cash flow was about $5 billion.

8

• The marginal cost of transactions is very low. For example, it costs less than

$10 to transfer huge sums of money using Fedwire and only a few cents to

make an ACH transfer.

• Float is drastically reduced. Wire transfers generate no float at all. This can result

in substantial savings. For example, cash managers at Occidental Petroleum

found that one plant was paying out about $8 million per month three to five

days early to avoid any risk of late fees if checks were delayed in the mail. The

solution was obvious: The plant’s managers switched to paying large bills

electronically; that way they could ensure they arrived exactly on time.

9

International Cash Management

Cash management in domestic firms is child’s play compared with that in large

multinational corporations operating in dozens of countries, each with its own cur-

rency, banking system, and legal structure.

A single, centralized cash management system is an unattainable ideal for these

companies, although they are edging toward it. For example, suppose that you are

the treasurer of a large multinational company with operations throughout Eu-

rope. You could allow the separate businesses to manage their own cash but that

would be costly and would almost certainly result in each one accumulating little

hoards of cash. The solution is to set up a regional system. In this case the company

establishes a local concentration account with a bank in each country. Then any

surplus cash is swept daily into central multicurrency accounts in London or an-

other European banking center. This cash is then invested in marketable securities

or used to finance any subsidiaries that have a cash shortage.

Payments also can be made out of the regional center. For example, to pay wages

in each European country, the company just needs to send its principal bank a com-

puter file with details of the payments to be made. The bank then finds the least

costly way to transfer the cash from the company’s central accounts and arranges

for the funds to be credited on the correct day to the employees in each country.

888 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

8

J. D. Moss, “Campbell Soup’s Cutting-Edge Cash Management,” Financial Executive 8 (September/

October 1992), pp. 39–42.

9

R. J. Pisapia, “The Cash Manager’s Expanding Role: Working Capital,” Journal of Cash Management 10

(November/December 1990), pp. 11–14.