Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Companies that maintain separate balances in each country are liable to find

that they have a cash surplus in one country and a shortage in another. In this case

the company could lend the surplus and borrow the deficit. However, that is likely

to be costly, since banks need to charge a higher rate to borrowers than they pay to

lenders. One alternative is to convert the surplus cash pool into the currency which

is in short supply, but the simpler solution is to arrange for the bank to pool all your

cash surpluses and shortages. In this case no money is transferred between ac-

counts. Instead, the bank just adds together the credit and debit balances and pays

you interest at its lending rate on the net surplus.

Most large multinationals have several banks in each country, but the more

banks they use, the less control they have over their cash balances. So development

of regional cash management systems favors banks that can offer a worldwide

branch network. These banks also can afford to invest the several billion dollars

that are needed to set up computer systems for handling cash payments and re-

ceipts in many different countries.

Paying for Bank Services

Much of the work of cash management—processing checks, transferring funds,

running lock boxes, helping keep track of the company’s accounts—is done by

banks. And banks provide many other services not so directly linked to cash man-

agement, such as handling payments and receipts in foreign currency or acting as

custodian for securities.

10

All these services have to be paid for. Usually payment is in the form of a

monthly fee, but banks may agree to waive the fee as long as the firm maintains a

minimum average balance in an interest-free deposit. Banks are prepared to do

this, because, after setting aside a portion of the money in a reserve account with

the Fed, they can relend the money to earn interest. Demand deposits earmarked

to pay for bank services are termed compensating balances. They used to be a very

common way to pay for bank services, but there has been a steady trend away from

using compensating balances and toward direct fees.

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 889

10

Of course, banks also lend money or give firms the option to borrow under a line of credit. See Section 30.6.

31.2 HOW MUCH CASH SHOULD THE FIRM HOLD?

Cash pays no interest. So why do individuals and corporations hold billions of dol-

lars in cash and demand deposits? Why, for example, don’t you take all your cash

and invest it in interest-bearing securities? The answer of course is that cash gives

you more liquidity than securities. You can use it to buy things. It is hard enough

getting New York cab drivers to give you change for a $20 bill, but try asking them

to split a Treasury bill.

In equilibrium all assets in the same risk class are priced to give the same expected

marginal benefit. The benefit from holding Treasury bills is the interest that you re-

ceive; the benefit from holding cash is that it gives you a convenient store of liquid-

ity. In equilibrium the marginal value of this liquidity is equal to the marginal value

of the interest on Treasury bills. This is just another way of saying that Treasury bills

are investments with zero net present value; they are fair value relative to cash.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Does this mean that it does not matter how much cash you hold? Of course not.

The marginal value of liquidity declines as you hold increasing amounts of cash.

When you have only a small proportion of your assets in cash, a little extra can be

extremely useful; when you have a substantial holding, any additional liquidity is

not worth much. Therefore, as financial manager you want to hold cash balances

up to the point where the marginal value of the liquidity is equal to the value of the

interest forgone.

If that seems more easily said than done, you may be comforted to know that

production managers must make a similar trade-off. Ask yourself why firms carry

inventories of raw materials. They are not obliged to do so; they could simply buy

materials day by day, as needed. But then they would pay higher prices for order-

ing in small lots, and they would risk production delays if the materials were not

delivered on time. That is why they order more than the firm’s immediate needs.

11

But there is a cost to holding inventories. Interest is lost on the money that is tied

up in inventories, storage must be paid for, and often there is spoilage and deteri-

oration. Therefore production managers try to strike a sensible balance between

the costs of holding too little inventory and those of holding too much.

It is exactly the same with cash. Cash is just another material that you require to

carry on production. If you keep too small a proportion of your funds in the bank, you

will need to make repeated sales of securities every time you want to pay your bills.

On the other hand, if you keep excessive cash in the bank, you are losing interest.

The Inventory Decision

Let us look at what economists have had to say about managing inventories and

then see whether some of these ideas may also help us to manage cash balances.

Here is a simple inventory problem.

Everyman’s Bookstore experiences a steady demand for Principles of Corporate

Finance from customers who find that it makes a serviceable doorstop. There are

two costs to holding an inventory of the book. First there is the carrying cost. This

includes the cost of the capital that is tied up in the inventory, the cost of the shelf

space, and so on. The second type of cost is the order cost. Each order involves a

fixed handling expense and delivery charge.

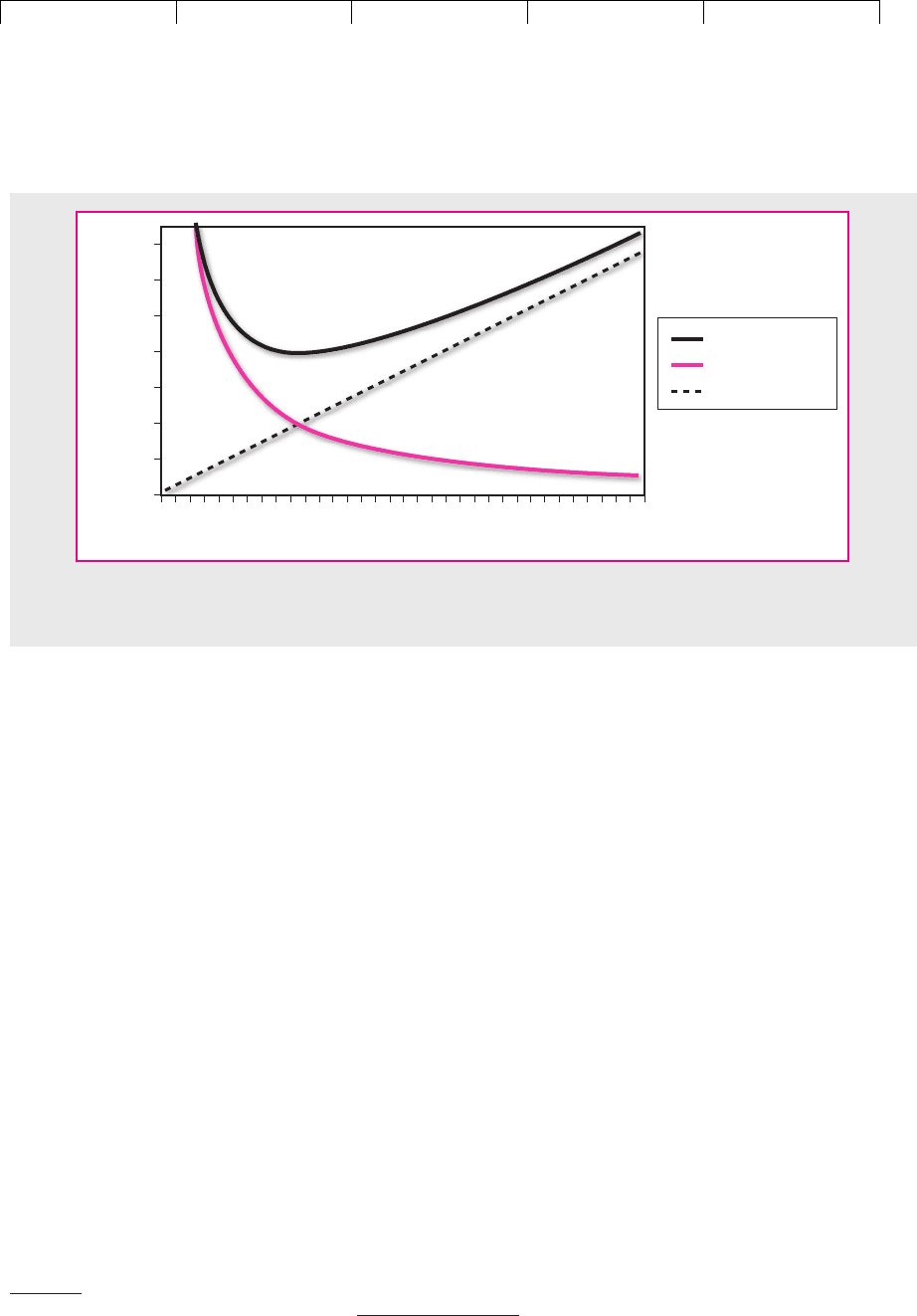

These two costs are the kernel of the inventory problem. An increase in order

size increases the average number of books in inventory, and therefore the carry-

ing cost rises. However, as the store increases its order size, the number of orders

falls, so that the order costs decline. The trick is to strike a sensible balance between

these two costs. When carrying costs are high, you should hold a smaller inventory

and replenish it more often. When order costs are high, you should hold a larger

inventory and place orders less frequently.

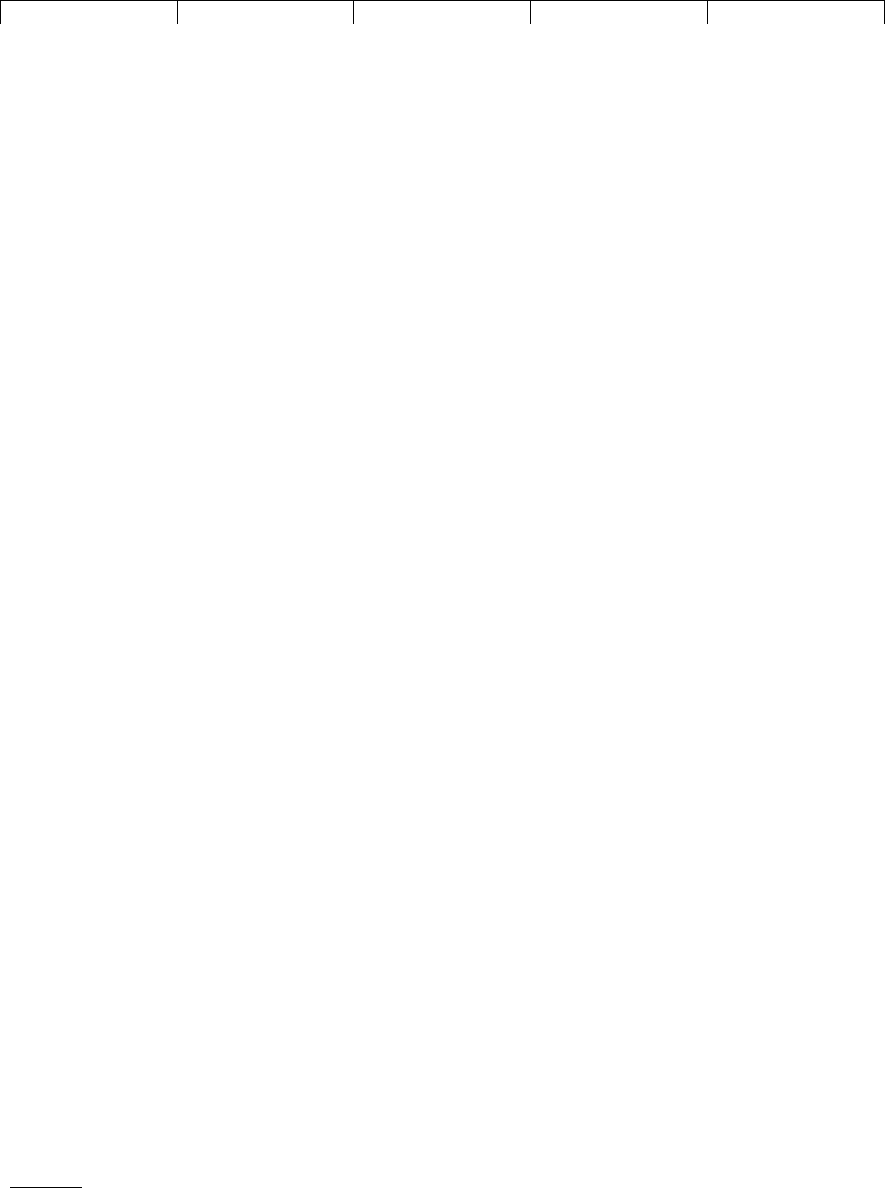

Some numbers may help to illustrate. Suppose that the bookstore sells 100

copies of the book a year. Suppose also that the carrying cost of inventory works

out at $4 per book and that each order placed with the publisher involves a fixed

order cost of $2. The upward sloping line in Figure 31.3 shows that carrying costs

increase in proportion to order size. The effect of order size on order costs is de-

890 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

11

Not much more in many manufacturing operations. “Just-in-time” assembly systems provide for a

continuous stream of parts deliveries, with no more than two or three hours’ worth of parts inventory

on hand. Financial managers likewise strive for just-in-time cash management systems, in which no

cash lies idle anywhere in the company’s business. This ideal is never quite reached because of the costs

and delays discussed in this chapter. Large corporations get close, however.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

picted by the downward sloping line. Order costs halve when the bookstore orders

two books at a time rather than one, but thereafter the savings from increases in or-

der size steadily diminish.

The upper curve in Figure 31.3 shows the sum of the carrying and order costs.

You can see that total costs are minimized when the store orders 10 books at a time.

Thus, 10 times a year the bookstore should place an order for 10 books and it

should work off this inventory over the following five weeks.

12

The Extension to Cash Balances

William Baumol was the first to point out that this simple inventory model can tell

us something about the management of cash balances.

13

Suppose that you keep a

reservoir of cash that is steadily drawn down to pay bills. When it runs out, you re-

plenish the cash balance by selling Treasury bills. The order cost is the fixed ad-

ministrative expense of each sale of Treasury bills. The main carrying cost of hold-

ing this cash is the interest that the firm is losing.

Deciding on the firm’s cash holding is exactly analogous to the problem of op-

timum order size faced by Everyman’s Bookstore. You just have to redefine the

variables. For example, instead of referring to the number of books per order, or-

der size becomes the amount of Treasury bills sold each time the cash balance is re-

plenished. Order cost becomes cost per sale of Treasury bills, while carrying cost is

just the interest lost from holding cash rather than bills.

If high interest rates increase the cost of carrying cash, you should hold a smaller

inventory of cash and therefore make smaller and more frequent sales of Treasury

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 891

1 4 7 10 13 16 19

Order size (number of books)

Total cost

Order cost

Carrying cost

22 25 28 31 34

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

Inventory costs ($)

FIGURE 31.3

Optimal order size involves a trade-off between order costs and carrying costs.

12

See the Principles of Corporate Finance Web page (www.mhhe.com/bm7e) for an explanation of how to

calculate the optimal order size.

13

W. J. Baumol, “The Transactions Demand for Cash: An Inventory Theoretic Approach,” Quarterly Jour-

nal of Economics 66 (November 1952), pp. 545–556.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

bills. On the other hand, if the firm incurs high costs in selling securities, you

should hold larger cash balances.

The Cash Management Trade-off

Baumol’s model of cash balances is unrealistic in one important respect: It assumes

that the firm is steadily using up its cash inventory. But that is not what usually

happens. In some weeks the firm may collect some large unpaid bills and therefore

receive a net inflow of cash. In other weeks it may pay its suppliers and so incur a

net outflow of cash. Some of these cash flows can be forecasted with confidence; in

other cases the amount of the flow or its timing is uncertain.

Economists and management scientists have developed a variety of more elab-

orate and realistic models that allow for the possibility of both cash inflows and

outflows.

14

But no model will ever succeed in capturing all the intricacies of the

firm’s cash requirements or provide a substitute for the judgment of the cash man-

ager. The importance of Baumol’s model and its many offspring is that they all

highlight the basic trade-off that the cash manager needs to make between the

fixed costs of selling securities and the carrying costs of holding cash balances.

Since there are economies of scale in buying or selling securities, the firm should

wait and place a sufficiently large order rather than place a series of smaller orders.

Baumol’s model helps us understand why small and medium-sized firms hold

significant cash balances. But for very large firms, the transaction costs of buying

and selling securities become trivial compared with the opportunity cost of hold-

ing idle cash balances.

Suppose that the interest rate is 8 percent per year, or roughly 8/365 ⫽ .022 per-

cent per day. Then the daily interest earned by $1 million is .00022 ⫻ 1,000,000 ⫽

$220. Even at a cost of $50 per transaction, which is generously high, it pays to buy

Treasury bills today and sell them tomorrow rather than to leave $1 million idle

overnight.

A corporation with $1 billion of annual sales has an average daily cash flow of

$1,000,000,000/365, about $2.7 million. Firms of this size end up buying or selling

securities once a day, every day, unless by chance they have only a small positive

cash balance at the end of the day.

Why do such firms hold any significant amounts of cash? There are basically

two reasons. First, cash may be left in non-interest-bearing accounts to compensate

banks for the services they provide. Second, large corporations may have literally

hundreds of accounts with dozens of different banks. It is often better to leave idle

cash in some of these accounts than to monitor each account daily and make daily

transfers between them.

One major reason for the proliferation of bank accounts is decentralized man-

agement. You cannot give a subsidiary operating autonomy without giving its

managers the right to spend and receive cash.

Good cash management nevertheless implies some degree of centralization. You

cannot maintain your desired inventory of cash if all the subsidiaries in the group

are responsible for their own private pools of cash. And you certainly want to

avoid situations in which one subsidiary is investing its spare cash at 8 percent

892 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

14

For example, the problem of cash management when inflows and outflows are unpredictable is ana-

lyzed in M. H. Miller and D. Orr, “A Model of the Demand for Money by Firms,” Quarterly Journal of

Economics 80 (August 1966), pp. 413–435. The Miller–Orr model is described in the Principles of Corpo-

rate Finance Web page.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

while another is borrowing at 10 percent. It is not surprising, therefore, that even

in highly decentralized companies there is generally central control over cash bal-

ances and bank relations.

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 893

31.3 INVESTING IDLE CASH

The Money Market

Temporary cash surpluses are generally invested in short-term securities. The mar-

ket for these short-term investments is known as the money market. The money

market has no physical marketplace. It consists of a loose agglomeration of banks

and dealers linked together by telex, telephones, and computers. But a huge volume

of securities is regularly traded on the money market, and competition is vigorous.

Most large corporations manage their own money-market investments, buy-

ing and selling through banks and dealers or over the Web. Small companies

sometimes find it more convenient to hire a professional investment manage-

ment firm or to put their cash into a money-market fund. This is a mutual fund

that invests only in low-risk, short-term securities. We discussed money-market

funds in Section 17.3.

Valuing Money-Market Investments

When we value long-term debt, it is important to take default risk into account. Al-

most anything may happen in 30 years, and even today’s most respectable com-

pany may get into trouble eventually. This is the basic reason that corporate bonds

offer higher yields than Treasury bonds.

Short-term debt is not risk-free either. When Penn Central failed, it had $82 mil-

lion of short-term commercial paper outstanding.

15

After that shock, investors be-

came much more discriminating in their purchases of commercial paper.

Such examples of failure are exceptions; in general, the danger of default is less

for money-market securities issued by corporations than for corporate bonds.

There are two reasons for this. First, the range of possible outcomes is smaller for

short-term investments. Even though the distant future may be clouded, you can

usually be confident that a particular company will survive for at least the next

month. Second, for the most part only well-established companies can borrow in

the money market. If you are going to lend money for only one day, you can’t af-

ford to spend too much time in evaluating the loan. Thus you will consider only

blue-chip borrowers.

Despite the high quality of money-market investments, there are often signifi-

cant differences in yield between corporate and U.S. government securities. Why

is this? One answer is the risk of default. Another is that the investments have dif-

ferent degrees of liquidity or “moneyness.” Investors like Treasury bills because

they are easier to turn into cash on short notice. Securities that cannot be converted

quickly and cheaply into cash need to offer relatively high yields.

During times of market turmoil investors often place a high value on having

ready access to cash. On such occasions the yield on illiquid securities can increase

dramatically. This happened in the fall of 1998 when a large hedge fund, Long

15

Commercial paper is short-term debt issued by corporations. We described it in Section 30.6.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Term Capital Management (LTCM), came close to collapse.

16

Fearful that LTCM

would be forced to liquidate its huge positions, investors shrank from securities

that could not be converted easily into cash. The spread between the yield on com-

mercial paper and Treasury bills rose to about 120 basis points (1.20 percent), al-

most four times its level at the beginning of the year.

Calculating the Yield on Money-Market Investments

Many money-market investments are pure discount securities. This means that

they don’t pay interest. The return consists of the difference between the amount

you pay and the amount you receive at maturity. Unfortunately, it is no good try-

ing to persuade the Internal Revenue Service that this difference represents capital

gain. The IRS is wise to that one and will tax your return as ordinary income.

Interest rates on money-market investments are often quoted on a discount ba-

sis. For example, suppose that six-month bills are issued at a discount of 5 percent.

This is rather a complicated way of saying that the price of a six-month bill is 100 ⫺

(6/12) ⫻ 5 ⫽ $97.50. Therefore, for every $97.5 that you invest today, you receive

$100 at the end of six months. The return over six months is 2.5/97.5 ⫽ .0256, or 2.56

percent. This is equivalent to an annual yield of 5.12 percent simple interest or 5.19

percent if interest is compounded annually. Note that the return is always higher

than the discount. When you read that an investment is selling at a discount of 5

percent, it is very easy to slip into the mistake of thinking that this is its return.

17

The International Money Market

In Chapter 24 we pointed out that there are two main markets for dollar bonds.

There is the domestic market in the United States and there is an international mar-

ket. Similarly, in this chapter we shall see that in addition to the domestic money

market, there is also an international market for short-term dollar investments.

Since this market is based largely in Europe, it has traditionally been known as the

eurodollar market. However, now that the European single currency has been called

the euro, the term “eurodollar” is potentially confusing and we will just refer to

“international dollars.”

An international dollar is not some strange bank note; it is simply a dollar de-

posit in a bank outside the United States. For example, suppose that an American

oil company buys crude oil from an Arab sheik and pays for it with a $1 million

check drawn on Chase Manhattan Bank. The sheik then deposits the check into his

account at Barclays Bank in London. As a result, Barclays has an asset in the form

of a $1 million credit in its account with Chase Manhattan. It also has an offsetting

liability in the form of a dollar deposit. That dollar deposit is placed in Europe; it

is, therefore, an international dollar deposit.

18

894 PART IX Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

16

Hedge funds specialize in making positive investments in securities that are believed to be underval-

ued, while selling short those that appear overvalued. The story of LTCM is told in R. Lowenstein, When

Genius Failed: The Rise and Fall of Long Term Capital Management, Random House, New York, 2000; and

N. Dunbar, Inventing Money: The Story of Long Term Capital Management and the Legends behind It, John

Wiley, New York, 2000.

17

To confuse things even more, dealers in the money market often quote rates as if there were only 360

days in a year. So a discount of 5 percent on a bill maturing in 182 days translates into a price of 100 ⫺

5 ⫻ (182/360) ⫽ 97.47 percent.

18

The sheik could equally well deposit the check with the London branch of a U.S. bank or a Japanese

bank. He would still have made an international dollar deposit.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We will describe the principal domestic and international dollar investments

shortly, but bear in mind that there is also an international market for investments

in other currencies. For example, if a U.S. corporation wishes to make a short-term

investment in yen, it can do so in the Tokyo money market or it can make an in-

ternational yen deposit in London.

If we lived in a world without regulation and taxes, the interest rate on an in-

ternational dollar loan would have to be the same as the rate on an equivalent do-

mestic dollar loan, the rate on an international yen loan would have to be the same

as that on a domestic yen loan, and so on. However, the international loan markets

thrive because individual governments attempt to regulate domestic bank lending.

For example, between 1963 and 1974 the U.S. government controlled the export of

funds for corporate investment. Therefore, companies that wished to expand

abroad were forced to borrow dollars outside the United States. This demand

tended to push the interest rate on these loans above the domestic rate. At the same

time the government limited the rate of interest that banks in the United States

could pay on domestic deposits; this also tended to keep the rate of interest that

you could earn on dollar deposits in Europe above the rate on domestic dollar de-

posits. By early 1974 the restrictions on the export of funds had been removed, and

for large deposits the interest rate ceiling had also been abolished. In consequence,

the difference between the interest rate on international dollar deposits and do-

mestic deposits narrowed, but it did not disappear: Banks are not subject to Fed-

eral Reserve requirements on international dollar deposits and are not obliged to

insure these deposits with the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation. On the

other hand, depositors are exposed to the (very low) risk that a foreign government

could prohibit banks from repaying international dollar deposits. For these reasons

international dollar investments continue to offer slightly higher rates of interest

than domestic dollar deposits.

The U.S. government has become increasingly concerned that its regulations are

driving banking business overseas to foreign banks and the overseas branches of

American banks. To attract some of this business back to the States, the government

in 1981 allowed U.S. and foreign banks to establish so-called international banking

facilities (IBFs). An IBF is the financial equivalent of a free-trade zone; it is physi-

cally situated in the United States, but it is not required to maintain reserves with

the Federal Reserve and depositors are not subject to any U.S. tax.

19

However,

there are tight restrictions on what business an IBF can conduct. In particular, it

cannot accept deposits from domestic United States corporations or make loans

to them.

Banks in London lend dollars to one another at the London interbank offered rate

(LIBOR). LIBOR is a benchmark for pricing many types of short-term loans in the

United States and overseas. For example, a corporation in the United States may

issue a floating-rate note with interest payments tied to LIBOR.

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 895

19

For these reasons dollars held on deposit in an IBF are also classed as international dollars.

31.4 MONEY-MARKET INVESTMENTS

Table 31.1 summarizes the principal money-market investments. We will describe

each in turn.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

896 PART IX Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

Basis for

Maturities Calculating

Investment Borrower When Issued Marketability Interest Comments

Treasury bills U.S. 4 weeks, Excellent Discount Auctioned weekly

government 3 months, secondary

or 6 months market

Federal FHLB, “Fannie Typically 3 to Very good Discount for Sold through

agency Mae,” “Sallie 6 months secondary securities dealers

discount Mae,” “Freddie market of 6 months

notes Mac,” etc. or less

Tax-exempt Municipalities, 3 months to Good secondary Usually Tax anticipation

municipal states, school 1 year market interest- notes (TANs),

notes districts, etc. bearing; revenue antici-

interest pation notes

at maturity (RANs), bond

anticipation

notes (BANs),

etc.

Tax-exempt Municipalities, 20 to 40 years Good secondary Variable interest Long-term bonds

variable-rate states, state market rate but with put

demand bonds universities, etc. options to

(VRDBs) demand

repayment

Non-negotiable Commercial banks, Usually 1 to 3 Poor secondary Interest-bearing Receipt for time

time deposits savings and months; also market for with interest deposit

and negotiable loans longer-maturity CDs at maturity

certificates of variable-rate

deposit (CDs) CDs

Commercial Industrial firms, Maximum 270 Dealers or issuer Usually Unsecured

paper (CP) finance companies, days; usually 60 will repurchase discount promissory

and bank holding days or less paper note; may be

companies; also placed through

municipalities dealer or

directly with

investor

Medium-term Largely finance Minimum 270 Dealers will Interest-bearing; Unsecured

notes (MTNs) companies and days; usually repurchase usually fixed promissory

banks; also less than notes rate note; placed

industrial firms 10 years through dealer

Bankers’ Major commercial 1 to 6 months Fair secondary Discount Demands to pay

acceptances banks market that have been

(BAs) accepted by a

bank

Repurchase Dealers in U.S. Overnight to No secondary Repurchase price Sales of

agreements government about 3 market set higher than government

(repos) securities months; also selling price; securities by

open repos difference dealer with

(continuing quoted as repo simultaneous

contracts) interest rate agreement to

repurchase

TABLE 31.1

Money-market investments in the United States.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

U.S. Treasury Bills

The first item in Table 31.1 is U.S. Treasury bills. These are usually issued weekly

and mature in four weeks, three months, or six months.

20

Sales are by auction. You

can enter a competitive bid and take your chance of receiving an allotment at your

bid price. Alternatively, if you want to be sure of getting your bills, you can enter

a noncompetitive bid. Noncompetitive bids are filled at the average price of the suc-

cessful competitive bids. You don’t have to participate in the auction to invest in

Treasury bills. There is also an excellent secondary market in which billions of dol-

lars of bills are bought and sold every day.

Federal Agency Securities

Agencies of the federal government such as the Federal Home Loan Bank (FHLB)

and the Federal National Mortgage Association (“Fannie Mae”) borrow both short

and long term. The short-term debt consists of discount notes, which are similar to

Treasury bills. They are very actively traded and are often held by corporations.

Their yields are slightly above those on comparable Treasury securities. One rea-

son for the slightly higher yields is that agency debt is not quite as marketable as

Treasury issues.

Another is that most agency debt is backed not by the “full faith and credit” of

the U.S. government but only by the agency itself.

21

Most investors do not believe

that the U.S. government would allow one of its agencies to default, but in 2000

their faith and the price of agency debt both took a knock when a senior Treasury

official reminded Congress that the government did not guarantee the debt. Sooth-

ing noises from the Treasury subsequently helped to reassure investors.

Short-Term Tax-Exempts

Short-term notes are also issued by municipalities, states, and agencies such as

state universities and school districts.

22

These are slightly more risky than Treasury

bills and not as easy to buy or sell.

23

Nevertheless they have one particular attrac-

tion—the interest is not subject to federal income tax.

24

Pretax yields on tax-exempts are substantially lower than those on comparable

taxed securities. But if your company pays tax at the standard 35 percent corporate

rate, the lower gross yield of the municipals may be more than offset by the sav-

ings in tax.

Tax-exempt issues also include variable-rate demand bonds (VRDBs). These are

long-term securities, whose interest payments are linked to the level of short-term

interest rates. Whenever the interest rate is reset, investors have the right to sell the

bonds back to the issuer for their face value. This ensures that on these reset dates

the price of the bonds cannot be less than their face value. Therefore, although

CHAPTER 31

Cash Management 897

20

So-called three-month bills actually mature 91 days after issue, and six-month bills mature 182 days

after issue.

21

The exception is Ginnie Mae, whose debt is guaranteed by the U.S. government.

22

Some of these notes are general obligations of the issuer; others are revenue securities, and in these cases

payments are made from rent receipts or other user charges.

23

Defaults on tax-exempts are rare but not unknown. For example, in 1983 the municipal utility Wash-

ington Public Power Supply System (unfortunately known as WPPSS) defaulted on $2.25 billion of

bonds. The 1994 default of Orange County is described in Section 13.4.

24

This advantage is partly offset by the fact that Treasury securities are free of state and local taxes.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IX. Financial Planning and

Short−Term Management

31. Cash Management

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

VRDBs are long-term bonds, their prices are very stable and they compete with

short-term tax-exempt notes as a home for spare cash.

Bank Time Deposits and Certificates of Deposit

If you make a time deposit with a bank, you are lending money to the bank for a fixed

period. If you need the money before maturity, the bank will usually allow you to

withdraw it but will exact a penalty in the form of a reduced rate of interest.

In the 1960s banks introduced the negotiable certificate of deposit (CD) for

time deposits of $1 million or more. In this case, when the bank borrows, it issues

a certificate of deposit, which is simply evidence of a time deposit with that bank.

If a lender needs the money before maturity, it can sell the CD to another investor.

When the loan matures, the new owner of the CD presents it to the bank and re-

ceives payment.

In recent years doubts about the creditworthiness of some banks have caused

the secondary market in CDs to become less active, so that CDs are now much

more like large non-negotiable time deposits.

25

Instead of depositing dollars with a bank in the United States, a corporation can

deposit them overseas with a foreign bank or the foreign branch of a U.S. bank. These

deposits pay a fixed rate of interest, and either they are for a fixed term that may vary

from one day to several years or they are for an undefined term but may be called at

one or more days’ notice. Since a time deposit is an illiquid investment, the London

branches of the major banks also issue negotiable international dollar CDs.

Commercial Paper

We described commercial paper in the last chapter so we will not discuss it here

beyond reminding you that it is short-term debt that is issued on a regular basis by

both financial and nonfinancial companies. Commercial paper is popular with

both industrial companies and money-market mutual funds as a parking place for

short-term cash.

Bankers’ Acceptances

In the next chapter we will explain how bankers’ acceptances (BAs) may be used

to finance exports or imports. An acceptance begins life as a written demand for

the bank to pay a given sum at a future date. The bank then agrees to this demand

by writing “accepted” on it. Once accepted, the draft becomes the bank’s IOU and

is a negotiable security that can be bought or sold through money-market dealers.

Acceptances by the large U.S. banks generally mature in one to six months and in-

volve very low credit risk.

Repurchase Agreements

Repurchase agreements, or repos, are effectively secured loans to a government se-

curity dealer. They work as follows: The investor buys part of the dealer’s holding

of Treasury securities and simultaneously arranges to sell them back again at a

later date at a specified higher price. The borrower (the dealer) is said to have en-

tered into a repo; the lender (who buys the securities) is said to have a reverse repo.

898 PART IX

Financial Planning and Short-Term Management

25

Some CDs are not negotiable at all and are therefore identical to time deposits. For example, banks may

sell low-value non-negotiable CDs to individuals.