Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 3. How to Calculate

Present Values

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

56 PART I Value

reveals a distant view of lights on the Hudson River. John Jones sits at a computer terminal,

glumly sipping a glass of chardonnay and trading Japanese yen over the Internet. His wife

Marsha enters.

Marsha: Hi, honey. Glad to be home. Lousy day on the trading floor, though. Dullsville.

No volume. But I did manage to hedge next year’s production from our copper mine. I

couldn’t get a good quote on the right package of futures contracts, so I arranged a com-

modity swap.

John doesn’t reply.

Marsha: John, what’s wrong? Have you been buying yen again? That’s been a losing trade

for weeks.

John: Well, yes. I shouldn’t have gone to Goldman Sachs’s foreign exchange brunch. But I’ve

got to get out of the house somehow. I’m cooped up here all day calculating covariances and

efficient risk-return tradeoffs while you’re out trading commodity futures. You get all the

glamour and excitement.

Marsha: Don’t worry dear, it will be over soon. We only recalculate our most efficient com-

mon stock portfolio once a quarter. Then you can go back to leveraged leases.

John: You trade, and I do all the worrying. Now there’s a rumor that our leasing company

is going to get a hostile takeover bid. I knew the debt ratio was too low, and you forgot to

put on the poison pill. And now you’ve made a negative-NPV investment!

Marsha: What investment?

John: Two more oil wells in that old field in Ohio. You spent $500,000! The wells only pro-

duce 20 barrels of crude oil per day.

Marsha: That’s 20 barrels day in, day out. There are 365 days in a year, dear.

John and Marsha’s teenage son Johnny bursts into the room.

Johnny: Hi, Dad! Hi, Mom! Guess what? I’ve made the junior varsity derivatives team!

That means I can go on the field trip to the Chicago Board Options Exchange. (Pauses.)

What’s wrong?

John: Your mother has made another negative-NPV investment. More oil wells.

Johnny: That’s OK, Dad. Mom told me about it. I was going to do an NPV calculation yes-

terday, but my corporate finance teacher asked me to calculate default probabilities for a

sample of junk bonds for Friday’s class.

(Grabs a financial calculator from his backpack.) Let’s see: 20 barrels per day times $15 per

barrel times 365 days per year . . . that’s $109,500 per year.

John: That’s $109,500 this year. Production’s been declining at 5 percent every year.

Marsha: On the other hand, our energy consultants project increasing oil prices. If they in-

crease with inflation, price per barrel should climb by roughly 2.5 percent per year. The

wells cost next to nothing to operate, and they should keep pumping for 10 more years at

least.

Johnny: I’ll calculate NPV after I finish with the default probabilities. Is a 9 percent nominal

cost of capital OK?

Marsha: Sure, Johnny.

John: (Takes a deep breath and stands up.) Anyway, how about a nice family dinner? I’ve re-

served our usual table at the Four Seasons.

Everyone exits.

Announcer: Were the oil wells really negative-NPV? Will John and Marsha have to fight a

hostile takeover? Will Johnny’s derivatives team use Black-Scholes or the binomial method?

Find out in the next episode of The Jones Family, Incorporated.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 3. How to Calculate

Present Values

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

CHAPTER 3 How to Calculate Present Values 57

You may not aspire to the Jones family’s way of life, but you will learn about all their activities, from

futures contracts to binomial option pricing, later in this book. Meanwhile, you may wish to replicate

Johnny’s NPV analysis.

Questions

1. Forecast future cash flows, taking account of the decline in production and the (par-

tially) offsetting forecasted increase in oil prices. How long does production have to

continue for the oil wells to be a positive-NPV investment? You can ignore taxes and

other possible complications.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER FOUR

58

THE VALUE OF

COMMON STOCKS

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

WE SHOULD WARN you that being a financial expert has its occupational hazards. One is being cor-

nered at cocktail parties by people who are eager to explain their system for making creamy profits

by investing in common stocks. Fortunately, these bores go into temporary hibernation whenever the

market goes down.

We may exaggerate the perils of the trade. The point is that there is no easy way to ensure su-

perior investment performance. Later in the book we will show that changes in security prices are

fundamentally unpredictable and that this result is a natural consequence of well-functioning cap-

ital markets. Therefore, in this chapter, when we propose to use the concept of present value to

price common stocks, we are not promising you a key to investment success; we simply believe that

the idea can help you to understand why some investments are priced higher than others.

Why should you care? If you want to know the value of a firm’s stock, why can’t you look up the

stock price in the newspaper? Unfortunately, that is not always possible. For example, you may be

the founder of a successful business. You currently own all the shares but are thinking of going pub-

lic by selling off shares to other investors. You and your advisers need to estimate the price at which

those shares can be sold. Or suppose that Establishment Industries is proposing to sell its concate-

nator division to another company. It needs to figure out the market value of this division.

There is also another, deeper reason why managers need to understand how shares are valued.

We have stated that a firm which acts in its shareholders’ interest should accept those investments

which increase the value of their stake in the firm. But in order to do this, it is necessary to under-

stand what determines the shares’ value.

We start the chapter with a brief look at how shares are traded. Then we explain the basic princi-

ples of share valuation. We look at the fundamental difference between growth stocks and income

stocks and the significance of earnings per share and price–earnings multiples. Finally, we discuss

some of the special problems managers and investors encounter when they calculate the present val-

ues of entire businesses.

A word of caution before we proceed. Everybody knows that common stocks are risky and that some

are more risky than others. Therefore, investors will not commit funds to stocks unless the expected

rates of return are commensurate with the risks. But we say next to nothing in this chapter about the

linkages between risk and expected return. A more careful treatment of risk starts in Chapter 7.

59

There are 9.9 billion shares of General Electric (GE), and at last count these shares

were owned by about 2.1 million shareholders. They included large pension

funds and insurance companies that each own several million shares, as well as

individuals who own a handful of shares. If you owned one GE share, you would

own .000002 percent of the company and have a claim on the same tiny fraction

of GE’s profits. Of course, the more shares you own, the larger your “share” of

the company.

If GE wishes to raise additional capital, it may do so by either borrowing or sell-

ing new shares to investors. Sales of new shares to raise new capital are said to oc-

cur in the primary market. But most trades in GE shares take place in existing shares,

which investors buy from each other. These trades do not raise new capital for the

firm. This market for secondhand shares is known as the secondary market. The

principal secondary marketplace for GE shares is the New York Stock Exchange

4.1 HOW COMMON STOCKS ARE TRADED

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

(NYSE).

1

This is the largest stock exchange in the world and trades, on an average

day, 1 billion shares in some 2,900 companies.

Suppose that you are the head trader for a pension fund that wishes to buy

100,000 GE shares. You contact your broker, who then relays the order to the floor

of the NYSE. Trading in each stock is the responsibility of a specialist, who keeps a

record of orders to buy and sell. When your order arrives, the specialist will check

this record to see if an investor is prepared to sell at your price. Alternatively, the

specialist may be able to get you a better deal from one of the brokers who is gath-

ered around or may sell you some of his or her own stock. If no one is prepared to

sell at your price, the specialist will make a note of your order and execute it as

soon as possible.

The NYSE is not the only stock market in the United States. For example, many

stocks are traded over the counter by a network of dealers, who display the prices at

which they are prepared to trade on a system of computer terminals known as

NASDAQ (National Association of Securities Dealers Automated Quotations Sys-

tem). If you like the price that you see on the NASDAQ screen, you simply call the

dealer and strike a bargain.

The prices at which stocks trade are summarized in the daily press. Here, for ex-

ample, is how The Wall Street Journal recorded the day’s trading in GE on July 2, 2001:

60 PART I

Value

1

GE shares are also traded on a number of overseas exchanges.

YTD

52 Weeks

Vol Net

% Chg Hi Lo Stock (SYM) Div Yld % PE 100s Last Chg

4.7 60.50 36.42 General Electric (GE) .64 1.3 38 215287 50.20 1.45

You can see that on this day investors traded a total of 215,287 100 21,528,700

shares of GE stock. By the close of the day the stock traded at $50.20 a share, up

$1.45 from the day before. The stock had increased by 4.7 percent from the start of

2001. Since there were about 9.9 billion shares of GE outstanding, investors were

placing a total value on the stock of $497 billion.

Buying stocks is a risky occupation. Over the previous year, GE stock traded as

high as $60.50, but at one point dropped to $36.42. An unfortunate investor who

bought at the 52-week high and sold at the low would have lost 40 percent of his

or her investment. Of course, you don’t come across such people at cocktail par-

ties; they either keep quiet or aren’t invited.

The Wall Street Journal also provides three other facts about GE’s stock. GE pays

an annual dividend of $.64 a share, the dividend yield on the stock is 1.3 percent,

and the ratio of the stock price to earnings (P/E ratio) is 38. We will explain shortly

why investors pay attention to these figures.

4.2 HOW COMMON STOCKS ARE VALUED

Think back to the last chapter, where we described how to value future cash flows.

The discounted-cash-flow (DCF) formula for the present value of a stock is just the

same as it is for the present value of any other asset. We just discount the cash flows

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

by the return that can be earned in the capital market on securities of comparable

risk. Shareholders receive cash from the company in the form of a stream of divi-

dends. So

PV(stock) PV(expected future dividends)

At first sight this statement may seem surprising. When investors buy stocks,

they usually expect to receive a dividend, but they also hope to make a capital gain.

Why does our formula for present value say nothing about capital gains? As we

now explain, there is no inconsistency.

Today’s Price

The cash payoff to owners of common stocks comes in two forms: (1) cash divi-

dends and (2) capital gains or losses. Suppose that the current price of a share is

P

0

, that the expected price at the end of a year is P

1

, and that the expected divi-

dend per share is DIV

1

. The rate of return that investors expect from this share

over the next year is defined as the expected dividend per share DIV

1

plus the ex-

pected price appreciation per share P

1

P

0

, all divided by the price at the start

of the year P

0:

This expected return is often called the market capitalization rate.

Suppose Fledgling Electronics stock is selling for $100 a share (P

0

100). In-

vestors expect a $5 cash dividend over the next year (DIV

1

5). They also expect

the stock to sell for $110 a year hence (P

1

110). Then the expected return to the

stockholders is 15 percent:

On the other hand, if you are given investors’ forecasts of dividend and price

and the expected return offered by other equally risky stocks, you can predict to-

day’s price:

For Fledgling Electronics DIV

1

5 and P

1

110. If r, the expected return on se-

curities in the same risk class as Fledgling, is 15 percent, then today’s price

should be $100:

How do we know that $100 is the right price? Because no other price could sur-

vive in competitive capital markets. What if P

0

were above $100? Then Fledgling

stock would offer an expected rate of return that was lower than other securities of

equivalent risk. Investors would shift their capital to the other securities and in the

process would force down the price of Fledgling stock. If P

0

were less than $100,

the process would reverse. Fledgling’s stock would offer a higher rate of return

than comparable securities. In that case, investors would rush to buy, forcing the

price up to $100.

P

0

5 110

1.15

$100

Price P

0

DIV

1

P

1

1 r

r

5 110 100

100

.15, or 15%

Expected return r

DIV

1

P

1

P

0

P

0

CHAPTER 4 The Value of Common Stocks 61

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The general conclusion is that at each point in time all securities in an equivalent

risk class are priced to offer the same expected return. This is a condition for equilibrium

in well-functioning capital markets. It is also common sense.

But What Determines Next Year’s Price?

We have managed to explain today’s stock price P

0

in terms of the dividend DIV

1

and the expected price next year P

1

. Future stock prices are not easy things to fore-

cast directly. But think about what determines next year’s price. If our price for-

mula holds now, it ought to hold then as well:

That is, a year from now investors will be looking out at dividends in year 2 and

price at the end of year 2. Thus we can forecast P

1

by forecasting DIV

2

and P

2

, and

we can express P

0

in terms of DIV

1

, DIV

2

, and P

2:

Take Fledgling Electronics. A plausible explanation why investors expect its

stock price to rise by the end of the first year is that they expect higher dividends

and still more capital gains in the second. For example, suppose that they are look-

ing today for dividends of $5.50 in year 2 and a subsequent price of $121. That

would imply a price at the end of year 1 of

Today’s price can then be computed either from our original formula

or from our expanded formula

We have succeeded in relating today’s price to the forecasted dividends for two

years (DIV

1

and DIV

2

) plus the forecasted price at the end of the second year (P

2

).

You will probably not be surprised to learn that we could go on to replace P

2

by

(DIV

3

P

3

)/(1 r) and relate today’s price to the forecasted dividends for three

years (DIV

1

, DIV

2

, and DIV

3

) plus the forecasted price at the end of the third year

(P

3

). In fact we can look as far out into the future as we like, removing P’s as we go.

Let us call this final period H. This gives us a general stock price formula:

The expression simply means the sum of the discounted dividends from year

1 to year H.

a

H

t1

a

H

t1

DIV

t

11 r2

t

P

H

11 r2

H

P

0

DIV

1

1 r

DIV

2

11 r2

2

…

DIV

H

P

H

11 r2

H

P

0

DIV

1

1 r

DIV

2

P

2

11 r2

2

5.00

1.15

5.50 121

11.152

2

$100

P

0

DIV

1

P

1

1 r

5.00 110

1.15

$100

P

1

5.50 121

1.15

$110

P

0

1

1 r

1DIV

1

P

1

2

1

1 r

aDIV

1

DIV

2

P

2

1 r

b

DIV

1

1 r

DIV

2

P

2

11 r2

2

P

1

DIV

2

P

2

1 r

62 PART I Value

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

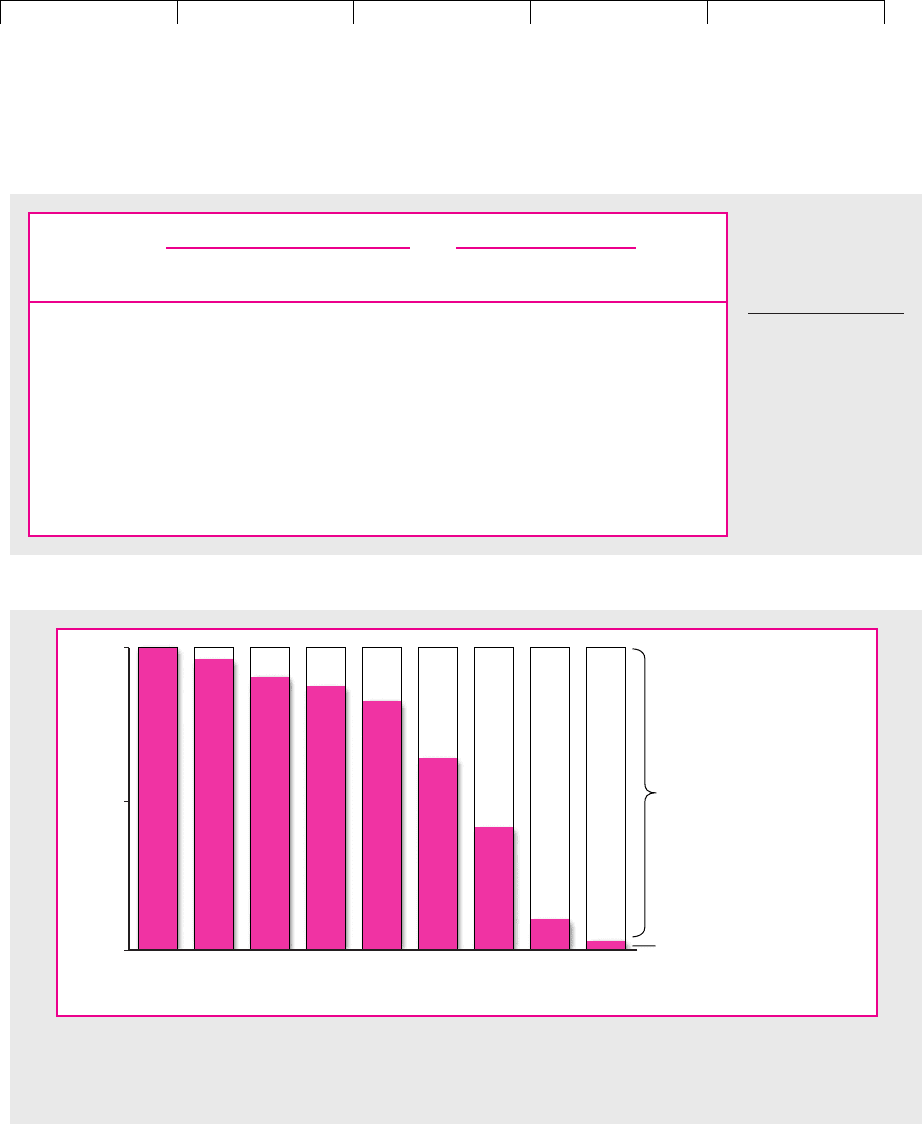

Table 4.1 continues the Fledgling Electronics example for various time horizons,

assuming that the dividends are expected to increase at a steady 10 percent com-

pound rate. The expected price P

t

increases at the same rate each year. Each line in

the table represents an application of our general formula for a different value of

H. Figure 4.1 provides a graphical representation of the table. Each column shows

the present value of the dividends up to the time horizon and the present value of

the price at the horizon. As the horizon recedes, the dividend stream accounts for

an increasing proportion of present value, but the total present value of dividends

plus terminal price always equals $100.

CHAPTER 4

The Value of Common Stocks 63

Expected Future Values Present Values

Horizon Cumulative Future

Period (H) Dividend (DIV

t

) Price (P

t

) Dividends Price Total

0 — 100 — — 100

1 5.00 110 4.35 95.65 100

2 5.50 121 8.51 91.49 100

3 6.05 133.10 12.48 87.52 100

4 6.66 146.41 16.29 83.71 100

10 11.79 259.37 35.89 64.11 100

20 30.58 672.75 58.89 41.11 100

50 533.59 11,739.09 89.17 10.83 100

100 62,639.15 1,378,061.23 98.83 1.17 100

TABLE 4.1

Applying the stock

valuation formula to

fledgling electronics.

Assumptions:

1. Dividends increase at

10 percent per year,

compounded.

2. Capitalization rate is

15 percent.

10050201043210

0

50

100

Present value, dollars

Horizon period

PV (dividends for 100 years)

PV (price at year 100)

FIGURE 4.1

As your horizon recedes, the present value of the future price (shaded area) declines but the present value of the

stream of dividends (unshaded area) increases. The total present value (future price and dividends) remains the same.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

How far out could we look? In principle the horizon period H could be infinitely

distant. Common stocks do not expire of old age. Barring such corporate hazards

as bankruptcy or acquisition, they are immortal. As H approaches infinity, the pres-

ent value of the terminal price ought to approach zero, as it does in the final col-

umn of Figure 4.1. We can, therefore, forget about the terminal price entirely and

express today’s price as the present value of a perpetual stream of cash dividends.

This is usually written as

where ⬁ indicates infinity.

This discounted-cash-flow (DCF) formula for the present value of a stock is just

the same as it is for the present value of any other asset. We just discount the cash

flows—in this case the dividend stream—by the return that can be earned in the

capital market on securities of comparable risk. Some find the DCF formula im-

plausible because it seems to ignore capital gains. But we know that the formula

was derived from the assumption that price in any period is determined by ex-

pected dividends and capital gains over the next period.

Notice that it is not correct to say that the value of a share is equal to the sum of

the discounted stream of earnings per share. Earnings are generally larger than

dividends because part of those earnings is reinvested in new plant, equipment,

and working capital. Discounting earnings would recognize the rewards of that in-

vestment (a higher future dividend) but not the sacrifice (a lower dividend today).

The correct formulation states that share value is equal to the discounted stream of

dividends per share.

P

0

a

∞

t1

DIV

t

11 r2

t

64 PART I Value

4.3 A SIMPLE WAY TO ESTIMATE

THE CAPITALIZATION RATE

In Chapter 3 we encountered some simplified versions of the basic present value

formula. Let us see whether they offer any insights into stock values. Suppose,

for example, that we forecast a constant growth rate for a company’s dividends.

This does not preclude year-to-year deviations from the trend: It means only

that expected dividends grow at a constant rate. Such an investment would be

just another example of the growing perpetuity that we helped our fickle phi-

lanthropist to evaluate in the last chapter. To find its present value we must di-

vide the annual cash payment by the difference between the discount rate and

the growth rate:

Remember that we can use this formula only when g, the anticipated growth rate,

is less than r, the discount rate. As g approaches r, the stock price becomes infinite.

Obviously r must be greater than g if growth really is perpetual.

Our growing perpetuity formula explains P

0

in terms of next year’s expected

dividend DIV

1

, the projected growth trend g, and the expected rate of return on

other securities of comparable risk r. Alternatively, the formula can be used to ob-

tain an estimate of r from DIV

1

, P

0

, and g:

P

0

DIV

1

r g

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 4. The Value of Common

Stocks

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The market capitalization rate equals the dividend yield (DIV

1

/P

0

) plus the ex-

pected rate of growth in dividends (g).

These two formulas are much easier to work with than the general statement

that “price equals the present value of expected future dividends.”

2

Here is a prac-

tical example.

Using the DCF Model to Set Gas and Electricity Prices

The prices charged by local electric and gas utilities are regulated by state com-

missions. The regulators try to keep consumer prices down but are supposed to al-

low the utilities to earn a fair rate of return. But what is fair? It is usually interpreted

as r, the market capitalization rate for the firm’s common stock. That is, the fair rate

of return on equity for a public utility ought to be the rate offered by securities that

have the same risk as the utility’s common stock.

3

Small variations in estimates of this return can have a substantial effect on the

prices charged to the customers and on the firm’s profits. So both utilities and reg-

ulators devote considerable resources to estimating r. They call r the cost of equity

capital. Utilities are mature, stable companies which ought to offer tailor-made

cases for application of the constant-growth DCF formula.

4

Suppose you wished to estimate the cost of equity for Pinnacle West Corp. in

May 2001, when its stock was selling for about $49 per share. Dividend payments

for the next year were expected to be $1.60 a share. Thus it was a simple matter to

calculate the first half of the DCF formula:

The hard part was estimating g, the expected rate of dividend growth. One op-

tion was to consult the views of security analysts who study the prospects for each

company. Analysts are rarely prepared to stick their necks out by forecasting divi-

dends to kingdom come, but they often forecast growth rates over the next five

years, and these estimates may provide an indication of the expected long-run

growth path. In the case of Pinnacle West, analysts in 2001 were forecasting an

Dividend yield

DIV

1

P

0

1.60

49

.033, or 3.3%

r

DIV

1

P

0

g

CHAPTER 4 The Value of Common Stocks 65

2

These formulas were first developed in 1938 by Williams and were rediscovered by Gordon and

Shapiro. See J. B. Williams, The Theory of Investment Value (Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press,

1938); and M. J. Gordon and E. Shapiro, “Capital Equipment Analysis: The Required Rate of Profit,”

Management Science 3 (October 1956), pp. 102–110.

3

This is the accepted interpretation of the U.S. Supreme Court’s directive in 1944 that “the returns to the

equity owner [of a regulated business] should be commensurate with returns on investments in other

enterprises having corresponding risks.” Federal Power Commission v. Hope Natural Gas Company, 302

U.S. 591 at 603.

4

There are many exceptions to this statement. For example, Pacific Gas & Electric (PG&E), which serves

northern California, used to be a mature, stable company until the California energy crisis of 2000 sent

wholesale electric prices sky-high. PG&E was not allowed to pass these price increases on to retail cus-

tomers. The company lost more than $3.5 billion in 2000 and was forced to declare bankruptcy in 2001.

PG&E is no longer a suitable subject for the constant-growth DCF formula.