Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 12 Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 339

14. Use the Market Insight database (www

.mhhe.com/edumarketinsight

) to estimate the

economic value added (EVA) for three firms. What problems did you encounter in do-

ing this?

CHALLENGE

QUESTIONS

1. Is there an optimal level of agency costs? How would you define it?

2. Suppose it were possible to measure and track economic income and the true economic

value of a firm’s assets. Would there be any remaining need for EVA? Discuss.

3. Reconstruct Table 12.9 assuming a steady-state growth rate of 10 percent per year. Your

answer will illustrate a fascinating theorem, namely, that book rate of return equals the

economic rate of return when the economic rate of return and the steady-state growth

rate are the same.

4. Consider an asset with the following cash flows:

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

Year

01 2 3

Cash flows ($ millions) ⫺12 ⫹5.20 ⫹4.80 ⫹4.40

The firm uses straight-line depreciation. Thus, for this project, it writes off $4 million

per year in years 1, 2, and 3. The discount rate is 10 percent.

a. Show that economic depreciation equals book depreciation.

b. Show that the book rate of return is the same in each year.

c. Show that the project’s book profitability is its true profitability.

You’ve just illustrated another interesting theorem. If the book rate of return is the same

in each year of a project’s life, the book rate of return equals the IRR.

5. The following are extracts from two newsletters sent to a stockbroker’s clients:

Investment Letter—March 2001

Kipper Parlors was founded earlier this year by its president, Albert Herring. It plans to open

a chain of kipper parlors where young people can get together over a kipper and a glass of wine

in a pleasant, intimate atmosphere. In addition to the traditional grilled kipper, the parlors serve

such delicacies as Kipper Schnitzel, Kipper Grandemere, and (for dessert) Kipper Sorbet.

The economics of the business are simple. Each new parlor requires an initial investment

in fixtures and fittings of $200,000 (the property itself is rented). These fixtures and fittings have

an estimated life of 5 years and are depreciated straight-line over that period. Each new parlor

involves significant start-up costs and is not expected to reach full profitability until its fifth

year. Profits per parlor are estimated as follows:

Year after Opening

12345

Profit 0 40 80 120 170

Depreciation 40 40 40 40 40

Profit after

depreciation –40 0 40 80 130

Book value at start

of year 200 160 120 80 40

Return on investment (%) –20 0 33 100 325

Kipper has just opened its first parlor and plans to open one new parlor each year. De-

spite the likely initial losses (which simply reflect start-up costs), our calculations show a dra-

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

340 PART III Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

matic profit growth and a long-term return on investment that is substantially higher than Kip-

per’s 20 percent cost of capital.

The total market value of Kipper stock is currently only $250,000. In our opinion, this does

not fully reflect the exciting growth prospects, and we strongly recommend clients to buy.

Investment Letter—April 2001

Albert Herring, president of Kipper Parlors, yesterday announced an ambitious new

building plan. Kipper plans to open two new parlors next year, three the year after, and so on.

We have calculated the implications of this for Kipper’s earnings per share and return on

investment. The results are extremely disturbing, and under the new plan, there seems to be

no prospect of Kipper’s ever earning a satisfactory return on capital.

Since March, the value of Kipper’s stock has fallen by 40 percent. Any investor who did

not heed our earlier warnings should take the opportunity to sell the stock now.

Compare Kipper’s accounting and economic income under the two expansion plans.

How does the change in plan affect the company’s return on investment? What is the

PV of Kipper stock? Ignore taxes in your calculations.

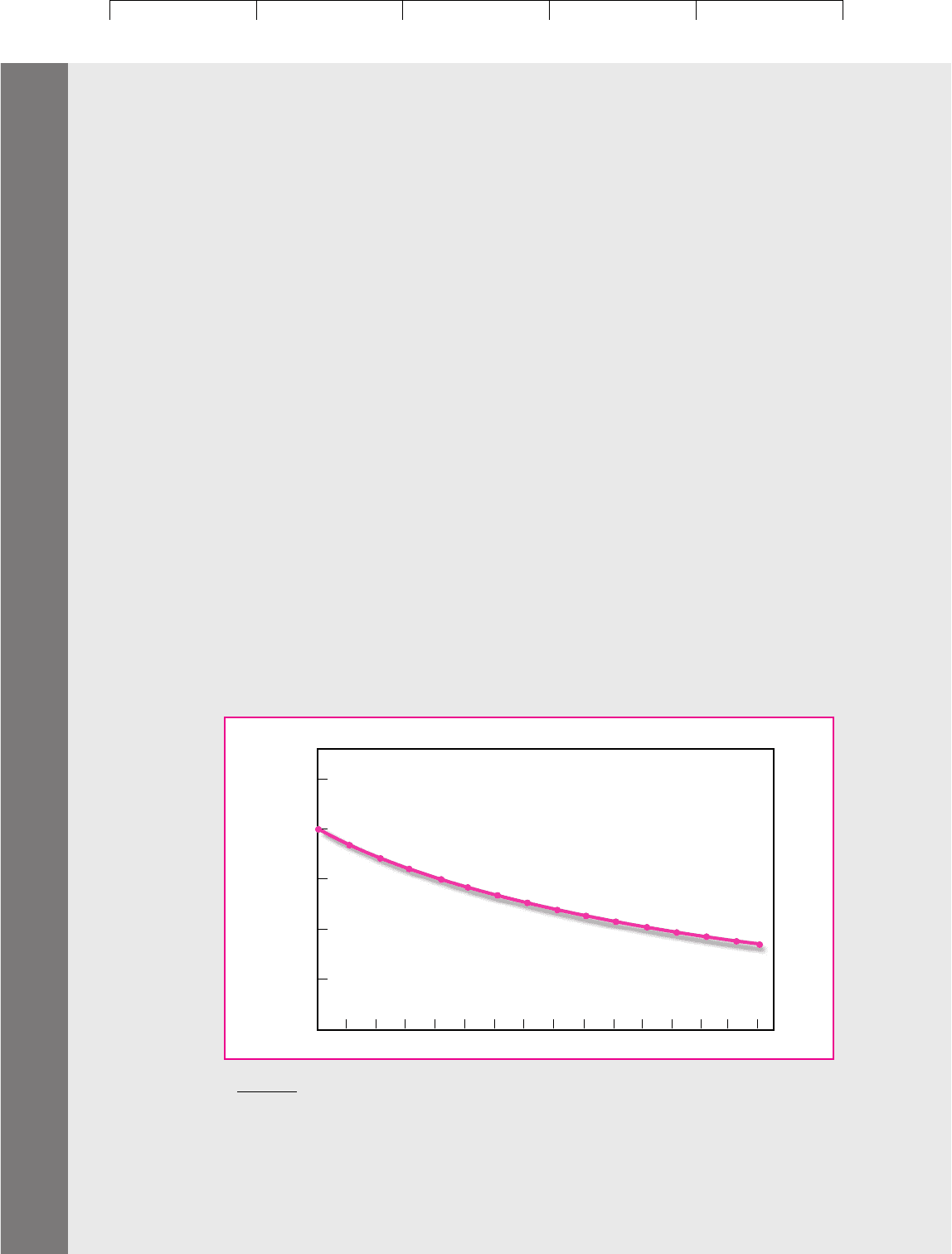

6. In our Nodhead example, true depreciation was decelerated. That is not always the

case. For instance, Figure 12.2 shows how on average the value of a Boeing 737 has

varied with its age.

28

Table 12.11 shows the market value at different points in the

plane’s life and the cash flow needed in each year to provide a 10 percent return. (For

example, if you bought a 737 for $19.69 million at the start of year 1 and sold it a year

later, your total profit would be 17.99 ⫹ 3.67 ⫺ 19.69 ⫽ $1.97 million, 10 percent of the

purchase cost.)

Many airlines write off their aircraft straight-line over 15 years to a salvage value

equal to 20 percent of the original cost.

a. Calculate economic and book depreciation for each year of the plane’s life.

b. Compare the true and book rates of return in each year.

c. Suppose an airline invested in a fixed number of Boeing 737s each year. Would

steady-state book return overstate or understate true return?

28

We are grateful to Mike Staunton for providing us with these estimates.

FIGURE 12.2

Estimated value of

Boeing 737 in

January 1987 as a

function of age.

Value, millions of dollars

$25

20

15

10

5

0

1

023 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 1413 15

Years

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 12 Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 341

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e

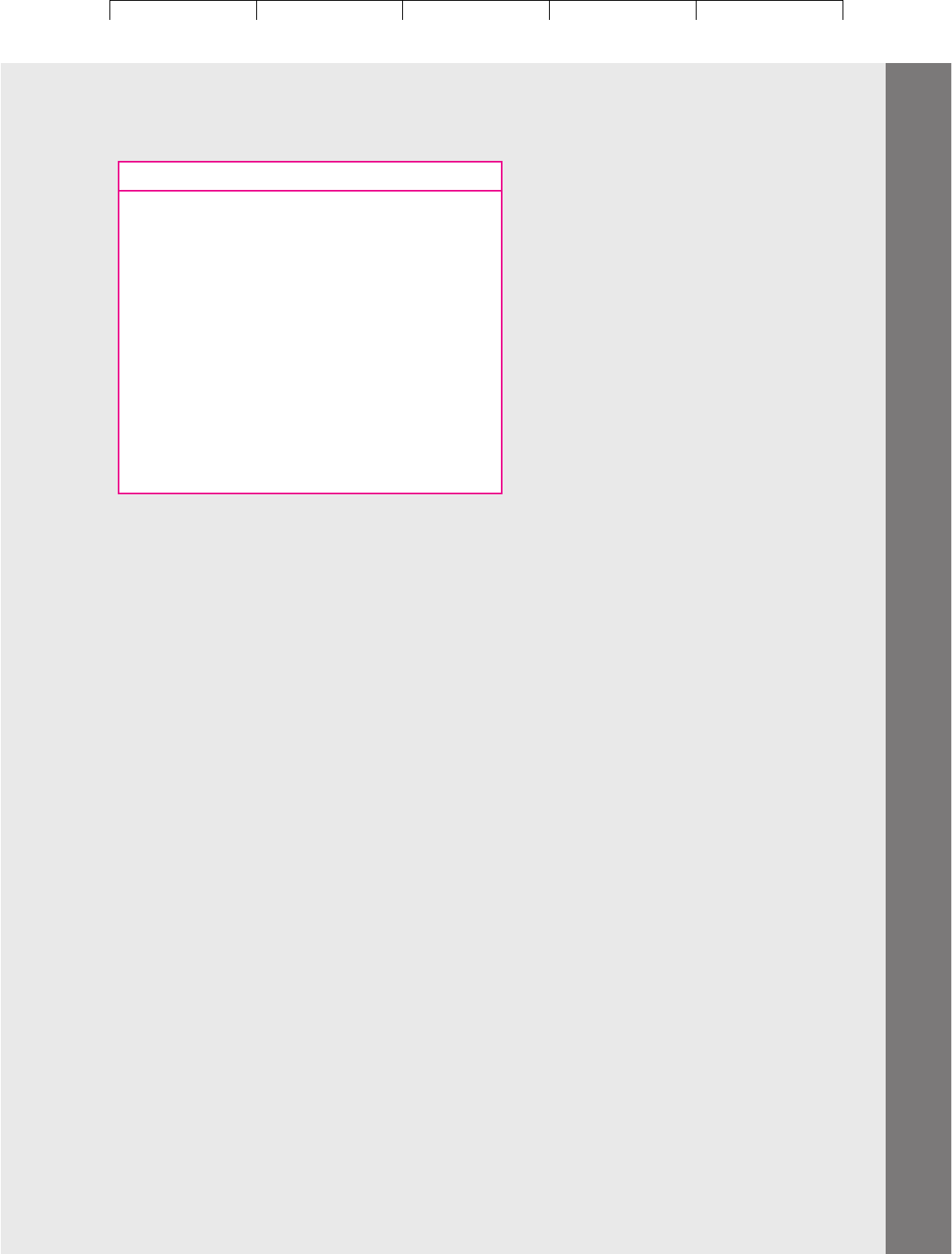

Start of Year Market Value Cash Flow

1 19.69

2 17.99 $3.67

3 16.79 3.00

4 15.78 2.69

5 14.89 2.47

6 14.09 2.29

7 13.36 2.14

8 12.68 2.02

9 12.05 1.90

10 11.46 1.80

11 10.91 1.70

12 10.39 1.61

13 9.91 1.52

14 9.44 1.46

15 9.01 1.37

16 8.59 1.32

TABLE 12.11

Estimated market values of a Boeing 737 in January 1987

as a function of age, plus the cash flows needed to provide

a 10 percent true rate of return (figures in $ millions).

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

# 39135 C t MH/BR A B l /M P N 342

RELATED WEBSITES

PART THREE

RELATED

WEBSITES

A discussion of capital budgeting procedures in

the context of IT investments:

www

.itpolicy.gsa.gov

Software for project analysis is available on:

www

.decisioneering.com

www

.kellogg.nwu.edu/faculty/myerson/

ftp/addins.htm

The following sites provide articles and data

on EVA:

www

.sternstewart.com

www

.financeadvisor.com

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER THIRTEEN

344

C O R P O R A T E

FINANCING AND THE

SIX LESSONS OF

MARKET EFFICIENCY

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

UP TO THIS point we have concentrated almost exclusively on the left-hand side of the balance

sheet—the firm’s capital expenditure decision. Now we move to the right-hand side and to the prob-

lems involved in financing the capital expenditures. To put it crudely, you’ve learned how to spend

money, now learn how to raise it.

Of course, we haven’t totally ignored financing in our discussion of capital budgeting. But we

made the simplest possible assumption: all-equity financing. That means we assumed the firm raises

its money by selling stock and then invests the proceeds in real assets. Later, when those assets gen-

erate cash flows, the cash is returned to the stockholders. Stockholders supply all the firm’s capital,

bear all the business risks, and receive all the rewards.

Now we are turning the problem around. We take the firm’s present portfolio of real assets and

its future investment strategy as given, and then we determine the best financing strategy. For

example,

• Should the firm reinvest most of its earnings in the business, or should it pay them out as

dividends?

• If the firm needs more money, should it issue more stock or should it borrow?

• Should it borrow short-term or long-term?

• Should it borrow by issuing a normal long-term bond or a convertible bond (i.e., a bond which

can be exchanged for stock by the bondholders)?

There are countless other financing trade-offs, as you will see.

The purpose of holding the firm’s capital budgeting decision constant is to separate that decision

from the financing decision. Strictly speaking, this assumes that capital budgeting and financing de-

cisions are independent. In many circumstances this is a reasonable assumption. The firm is generally

free to change its capital structure by repurchasing one security and issuing another. In that case

there is no need to associate a particular investment project with a particular source of cash. The firm

can think, first, about which projects to accept and, second, about how they should be financed.

Sometimes decisions about capital structure depend on project choice or vice versa, and in those

cases the investment and financing decisions have to be considered jointly. However, we defer dis-

cussion of such interactions of financing and investment decisions until later in the book.

We start this chapter by contrasting investment and financing decisions. The objective in each case

is the same—to maximize NPV. However, it may be harder to find positive-NPV financing opportuni-

ties. The reason it is difficult to add value by clever financing decisions is that capital markets are ef-

ficient. By this we mean that fierce competition between investors eliminates profit opportunities and

causes debt and equity issues to be fairly priced. If you think that sounds like a sweeping statement,

you are right. That is why we have devoted this chapter to explaining and evaluating the efficient-

market hypothesis.

You may ask why we start our discussion of financing issues with this conceptual point, before you

have even the most basic knowledge about securities and issue procedures. We do it this way be-

cause financing decisions seem overwhelmingly complex if you don’t learn to ask the right questions.

We are afraid you might flee from confusion to the myths that often dominate popular discussion of

corporate financing. You need to understand the efficient-market hypothesis not because it is uni-

versally true but because it leads you to ask the right questions.

We define the efficient-market hypothesis more carefully in Section 13.2. The hypothesis comes in

different strengths, depending on the information available to investors. Sections 13.2 and 13.3 re-

view the evidence for and against efficient markets. The evidence “for” is massive, but over the years

a number of puzzling anomalies have accumulated.

The chapter closes with the six lessons of market efficiency.

345

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Although it is helpful to separate investment and financing decisions, there are ba-

sic similarities in the criteria for making them. The decisions to purchase a machine

tool and to sell a bond each involve valuation of a risky asset. The fact that one as-

set is real and the other is financial doesn’t matter. In both cases we end up com-

puting net present value.

The phrase net present value of borrowing may seem odd to you. But the follow-

ing example should help to explain what we mean: As part of its policy of encour-

aging small business, the government offers to lend your firm $100,000 for 10 years

at 3 percent. This means that the firm is liable for interest payments of $3,000 in

each of the years 1 through 10 and that it is responsible for repaying the $100,000

in the final year. Should you accept this offer?

We can compute the NPV of the loan agreement in the usual way. The one dif-

ference is that the first cash flow is positive and the subsequent flows are negative:

The only missing variable is r, the opportunity cost of capital. You need that to

value the liability created by the loan. We reason this way: The government’s loan

to you is a financial asset: a piece of paper representing your promise to pay $3,000

per year plus the final repayment of $100,000. How much would that paper sell for

if freely traded in the capital market? It would sell for the present value of those

cash flows, discounted at r, the rate of return offered by other securities issued by

your firm. All you have to do to determine r is to answer the question, What inter-

est rate would my firm have to pay to borrow money directly from the capital mar-

kets rather than from the government?

Suppose that this rate is 10 percent. Then

Of course, you don’t need any arithmetic to tell you that borrowing at 3 percent is

a good deal when the fair rate is 10 percent. But the NPV calculations tell you just

how much that opportunity is worth ($43,012).

1

It also brings out the essential sim-

ilarity of investment and financing decisions.

Differences between Investment and Financing Decisions

In some ways investment decisions are simpler than financing decisions. The number

of different financing decisions (i.e., securities) is continually expanding. You will

have to learn the major families, genera, and species. You will also need to become fa-

miliar with the vocabulary of financing. You will learn about such matters as caps,

strips, swaps, and bookrunners; behind each of these terms lies an interesting story.

⫽⫹100,000 ⫺ 56,988 ⫽⫹$43,012

NPV ⫽⫹100,000 ⫺

a

10

t⫽1

3,000

11.102

t

⫺

100,000

11.102

10

⫽⫹100,000 ⫺

a

10

t⫽1

3,000

11 ⫹ r2

t

⫺

100,000

11 ⫹ r2

10

⫺present value of loan repayment

NPV ⫽ amount borrowed ⫺ present value of interest payments

346 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

13.1 WE ALWAYS COME BACK TO NPV

1

We ignore here any tax consequences of borrowing. These are discussed in Chapter 18.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

There are also ways in which financing decisions are much easier than invest-

ment decisions. First, financing decisions do not have the same degree of finality

as investment decisions. They are easier to reverse. That is, their abandonment

value is higher. Second, it’s harder to make or lose money by smart or stupid fi-

nancing strategies. That is, it is difficult to find financing schemes with NPVs sig-

nificantly different from zero. This reflects the nature of the competition.

When the firm looks at capital investment decisions, it does not assume that it is

facing perfect, competitive markets. It may have only a few competitors that spe-

cialize in the same line of business in the same geographical area. And it may own

some unique assets that give it an edge over its competitors. Often these assets are

intangible, such as patents, expertise, or reputation. All this opens up the oppor-

tunity to make superior profits and find projects with positive NPVs.

In financial markets your competition is all other corporations seeking funds, to

say nothing of the state, local, and federal governments that go to New York, Lon-

don, and other financial centers to raise money. The investors who supply financ-

ing are comparably numerous, and they are smart: Money attracts brains. The fi-

nancial amateur often views capital markets as segmented, that is, broken down into

distinct sectors. But money moves between those sectors, and it moves fast.

Remember that a good financing decision generates a positive NPV. It is one in

which the amount of cash raised exceeds the value of the liability created. But turn

that statement around. If selling a security generates a positive NPV for the seller,

it must generate a negative NPV for the buyer. Thus, the loan we discussed was a

good deal for your firm but a negative NPV from the government’s point of view.

By lending at 3 percent, it offered a $43,012 subsidy.

What are the chances that your firm could consistently trick or persuade in-

vestors into purchasing securities with negative NPVs to them? Pretty low. In gen-

eral, firms should assume that the securities they issue are fairly priced. That takes

us into the main topic of this chapter: efficient capital markets.

CHAPTER 13

Corporate Financing and the Six Lessons of Market Efficiency 347

13.2 WHAT IS AN EFFICIENT MARKET?

A Startling Discovery: Price Changes Are Random

As is so often the case with important ideas, the concept of efficient capital markets

stemmed from a chance discovery. In 1953 Maurice Kendall, a British statistician,

presented a controversial paper to the Royal Statistical Society on the behavior of

stock and commodity prices.

2

Kendall had expected to find regular price cycles,

but to his surprise they did not seem to exist. Each series appeared to be “a ‘wan-

dering’ one, almost as if once a week the Demon of Chance drew a random num-

ber . . . and added it to the current price to determine the next week’s price.” In

other words, the prices of stocks and commodities seemed to follow a random walk.

2

See M. G. Kendall, “The Analysis of Economic Time Series, Part I. Prices,” Journal of the Royal Statisti-

cal Society 96 (1953), pp. 11–25. Kendall’s idea was not wholly new. It had been proposed in an almost

forgotten thesis written 53 years earlier by a French doctoral student, Louis Bachelier. Bachelier’s ac-

companying development of the mathematical theory of random processes anticipated by five years

Einstein’s famous work on the random Brownian motion of colliding gas molecules. See L. Bachelier,

Theorie de la Speculation, Gauthiers-Villars, Paris, 1900. Reprinted in English (A. J. Boness, trans.) in P. H.

Cootner (ed.), The Random Character of Stock Market Prices, M.I.T. Press, Cambridge, MA, 1964, pp. 17–78.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

If you are not sure what we mean by “random walk,” you might like to think of

the following example: You are given $100 to play a game. At the end of each week

a coin is tossed. If it comes up heads, you win 3 percent of your investment; if it is

tails, you lose 2.5 percent. Therefore, your capital at the end of the first week is ei-

ther $103.00 or $97.50. At the end of the second week the coin is tossed again. Now

the possible outcomes are:

348 PART IV

Financing Decisions and Market Efficiency

This process is a random walk with a positive drift of .25 percent per week.

3

It

is a random walk because successive changes in value are independent. That is, the

odds each week are the same, regardless of the value at the start of the week or of

the pattern of heads and tails in the previous weeks.

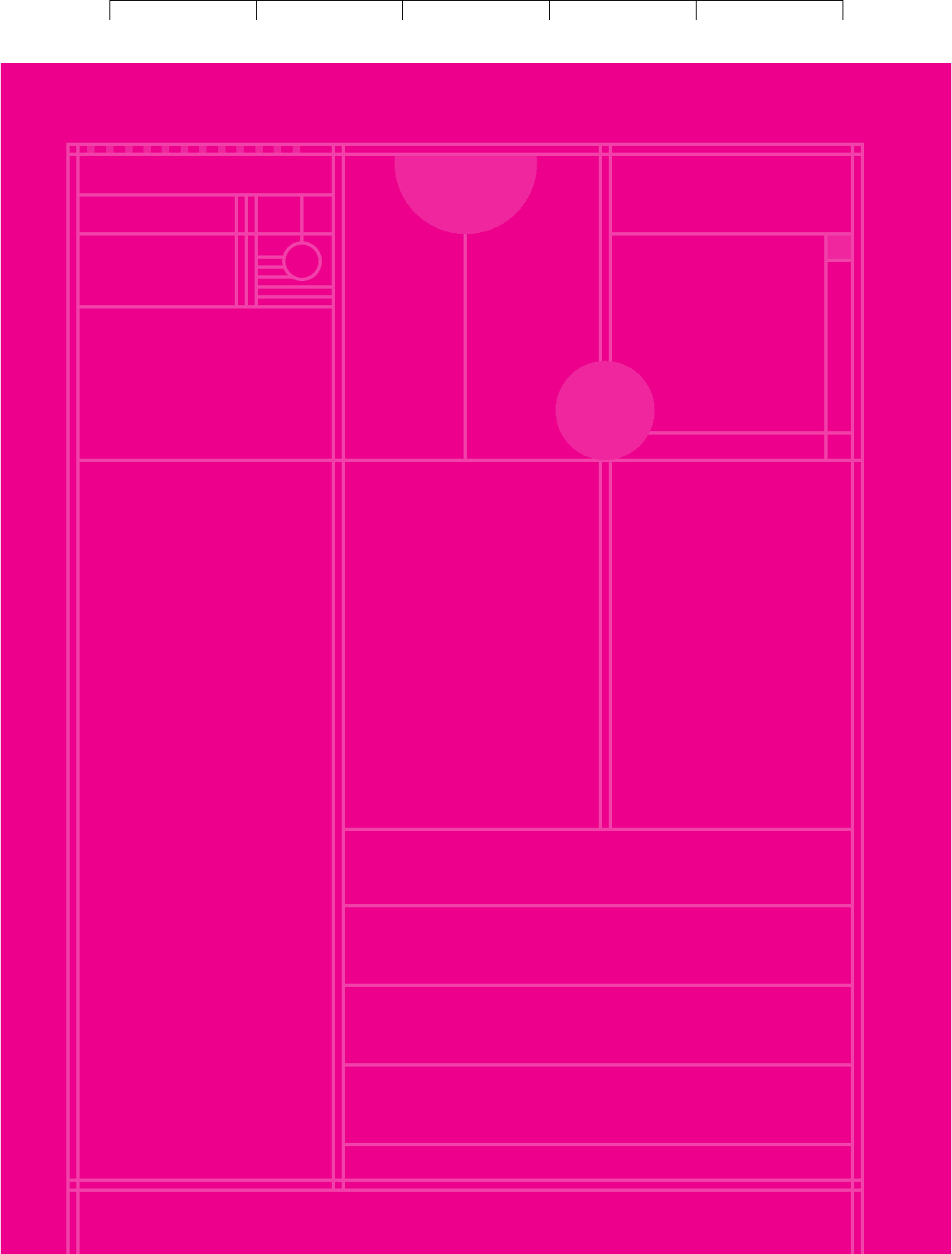

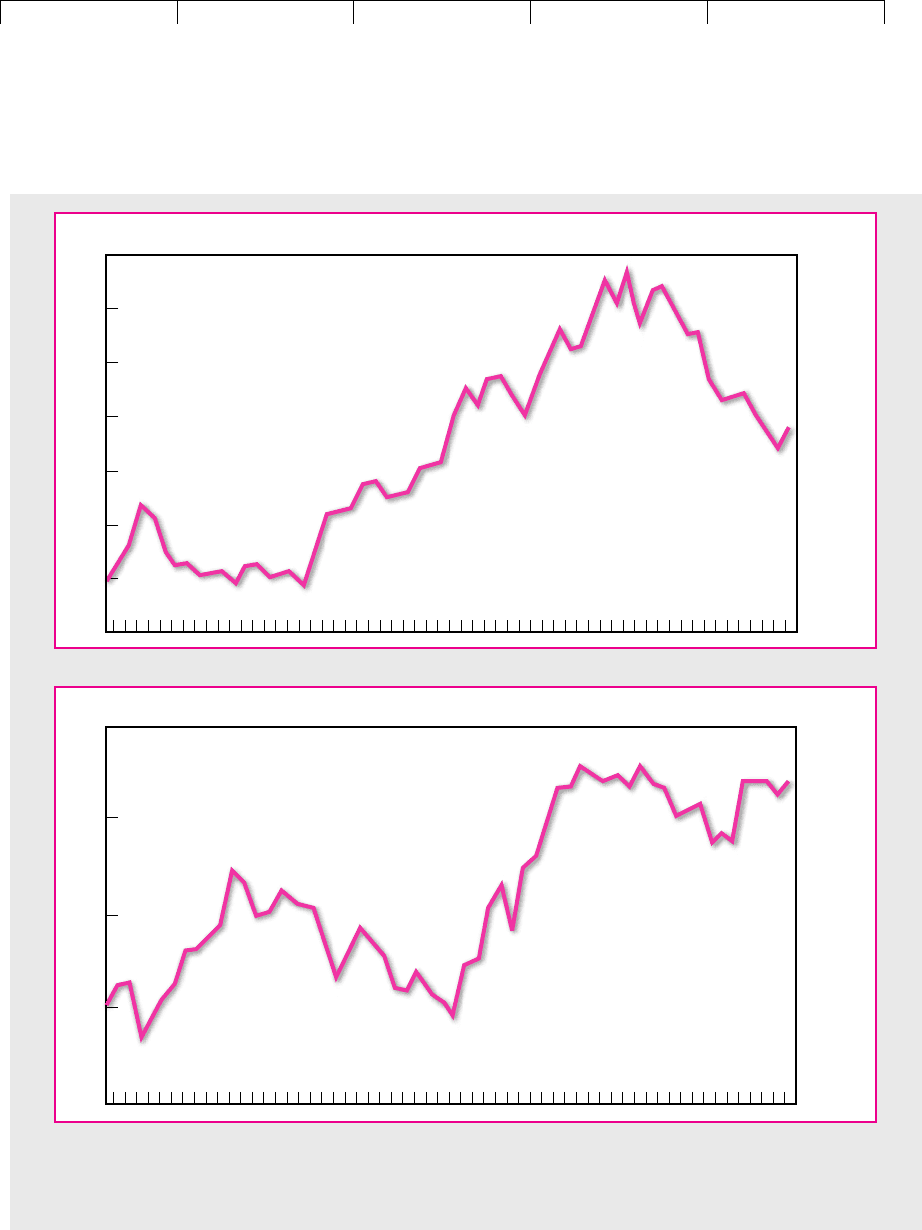

If you find it difficult to believe that there are no patterns in share price changes,

look at the two charts in Figure 13.1. One of these charts shows the outcome from

playing our game for five years; the other shows the actual performance of the Stan-

dard and Poor’s Index for a five-year period. Can you tell which one is which?

4

When Maurice Kendall suggested that stock prices follow a random walk, he

was implying that the price changes are independent of one another just as the

gains and losses in our coin-tossing game were independent. Figure 13.2 illustrates

this. Each dot shows the change in the price of Microsoft stock on successive days.

The circled dot in the southeast quadrant refers to a pair of days in which a 1 per-

cent increase was followed by a 1 percent decrease. If there was a systematic ten-

dency for increases to be followed by decreases, there would be many dots in the

southeast quadrant and few in the northeast quadrant. It is obvious from a glance

that there is very little pattern in these price movements, but we can test this more

precisely by calculating the coefficient of correlation between each day’s price

change and the next. If price movements persisted, the correlation would be posi-

tive; if there was no relationship, it would be 0. In our example, the correlation be-

tween successive price changes in Microsoft stock was ⫹.022; there was a negligi-

ble tendency for price rises to be followed by further price rises.

5

$100

$97.50

$103.00

$106.09

$100.43

Heads

Tails

$100.43

$95.06

Heads

Tails

Heads

Tails

3

The drift is equal to the expected outcome: (1/2) (3) ⫹ (1/2) (⫺2.5) ⫽ .25%.

4

The bottom chart in Figure 13.1 shows the real Standard and Poor’s Index for the years 1980 through

1984; the top chart is a series of cumulated random numbers. Of course, 50 percent of you are likely to

have guessed right, but we bet it was just a guess. A similar comparison between cumulated random

numbers and actual price series was first suggested by H. V. Roberts, “Stock Market ‘Patterns’ and Fi-

nancial Analysis: Methodological Suggestions,” Journal of Finance 14 (March 1959), pp. 1–10.

5

The correlation coefficient between successive observations is known as the autocorrelation coefficient.

An autocorrelation of ⫹.022 implies that, if Microsoft stock price rose by 1 percent more than average

yesterday, your best forecast of today’s price change would be a rise of .022 percent more than average.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

IV. Financial Decisions and

Market Efficiency

13. Corporate Financing

and the Six Lessons of

Market Efficiency

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Figure 13.2 suggests that Microsoft’s price changes were effectively uncorre-

lated. Today’s price change gave investors almost no clue as to the likely change

tomorrow. Does that surprise you? If so, imagine that it were not the case and that

changes in Microsoft’s stock price were expected to persist for several months.

Figure 13.3 provides an example of such a predictable cycle. You can see that an

CHAPTER 13

Corporate Financing and the Six Lessons of Market Efficiency 349

Level

200

220

180

160

140

120

100

80

Months

Level

160

140

120

100

80

Months

FIGURE 13.1

One of these charts shows the Standard and Poor’s Index for a five-year period. The other shows the results of

playing our coin-tossing game for five years. Can you tell which is which?