Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Compensation can be based on input (for example, the manager’s effort or

demonstrated willingness to bear risk) or on output (actual return or value added

as a result of the manager’s decisions). But input is so difficult to measure; for ex-

ample, how does an outside investor observe effort? Therefore incentives are al-

most always based on output. The trouble is that output depends not just on the

manager’s decisions but also on many other events outside his or her control.

The fortunes of a business never depend only on the efforts of a few key indi-

viduals. The state of the economy or the industry is usually at least as important

for the firm’s success. Unless you can separate out these influences, you face a

dilemma. You want to provide managers with a high-powered incentive, so that

they capture all the benefits of their contributions to the firm, but such an

arrangement would load onto the managers all the risk of fluctuations in the

firm’s value. Think of what this would mean in the case of GE, where in a reces-

sion income can fall by more than $1 billion. No group of managers would have

the wealth to stump up a significant fraction of $1 billion, and they would cer-

tainly be reluctant to take on the risk of huge personal losses in a recession. A re-

cession is not their fault.

The result is a compromise. Firms do link managers’ pay to performance, but

fluctuations in firm value are shared by managers and shareholders. Managers

bear some of the risks that are outside their control and shareholders bear some of

the agency costs if managers shirk, empire build, or otherwise fail to maximize

value. Thus, some agency costs are inevitable. For example, since managers split

the gains from hard work with the stockholders but reap all the personal benefits

of an idle or indulgent life, they will be tempted to put in less effort than if share-

holders could reward their effort perfectly.

If the firm’s fortunes are largely outside managers’ control, it makes sense to of-

fer the managers low-powered incentives. In such cases the managers’ compensa-

tion should be largely in the form of a fixed salary. If success depends almost ex-

clusively on individual skill and effort, then managers are given high-powered

incentives and end up bearing substantial risks. For example, a large part of the

compensation of traders and salespeople in securities firms is in the form of

bonuses or stock options.

How do managers of large corporations share in the fortunes of their firms?

Michael Jensen and Kevin Murphy found that the median holding of chief ex-

ecutive officers (CEOs) in their firms was only .14 percent of the outstanding

shares. On average, for every $1,000 addition to shareholder wealth, the CEO re-

ceived $3.25 in extra compensation. Jensen and Murphy conclude that “corpo-

rate America pays its most important leaders like bureaucrats,” and ask “Is it

any wonder then that so many CEOs act like bureaucrats rather than the value-

maximizing entrepreneurs companies need to enhance their standing in world

markets?”

10

Jensen and Murphy may overstate their case. It is true that managers bear only

a small portion of the gains and losses in firm value. However, the payoff to the

manager of a large, successful firm can still be very large. For example, when

CHAPTER 12

Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 319

10

M. C. Jensen and K. Murphy, “CEO Incentives—It’s Not How Much You Pay, But How,” Harvard Busi-

ness Review 68 (May–June 1990), p. 138. The data for Jensen and Murphy’s study ended in 1983. Hall

and Liebman have updated the study and argue that the sensitivity of compensation to changes in firm

value has increased significantly. See B. J. Hall and J. B. Liebman, “Are CEOs Really Paid Like Bureau-

crats?” Harvard University working paper, August 1997.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Michael Eisner was hired as CEO by the Walt Disney Company, his compensation

package had three main components: a base annual salary of $750,000; an annual

bonus of 2 percent of Disney’s net income above a threshold of normal profitabil-

ity; and a 10-year option that allowed him to purchase 2 million shares of stock for

$14 a share, which was about the price of Disney stock at the time. As it turned out,

by the end of Eisner’s six-year contract the value of Disney shares had increased

by $12 billion, more than sixfold. While Eisner received only 1.6 percent of that gain

in value as compensation, this still amounted to $190 million.

11

Because most CEOs own stock and stock options in their firms, managers of

poorly performing firms often actually lose money; they also often lose their jobs.

For example, a study of the remuneration of the chief executives of large U.S. firms

found that the heads of firms that were in the top 10 percent in terms of stock mar-

ket performance received over $9 million more in compensation than their

brethren at the bottom 10 percent of the spectrum.

12

Chief executives in the United States are generally paid more than those in other

countries and their pay is more closely tied to stock returns. For example, Kaplan

found that top managers in the United States earn salary plus bonus five times that

of their Japanese counterparts, although Japanese managers receive more noncash

compensation. The United States managers’ stakes in their companies averaged

more than double the Japanese managers’ stakes.

13

In the ideal incentive scheme, management should bear all the consequences of

their own actions, but should not be exposed to the fluctuations in firm value over

which they have no control. That raises a question: Managers are not responsible

for fluctuations in the general level of the stock market. So why don’t companies

tie top management’s compensation to stock returns relative to the market or to the

firm’s close competitors? This would tie managers’ compensation somewhat more

closely to their own contributions.

Tying top management compensation to stock prices raises another difficult is-

sue. The market value of a company’s shares reflects investors’ expectations. The

stockholders’ return depends on how well the company performs relative to ex-

pectations. For example, suppose a company announces the appointment of an

outstanding new manager. The stock price leaps up in anticipation of improved

performance. Thenceforth, if the new manager delivers exactly the good perfor-

mance that investors expected, the stock will earn only a normal, average rate of

return. In this case a compensation scheme linked to the stock return would fail to

recognize the manager’s special contribution.

320 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

11

We don’t know whether Michael Eisner’s contribution to the firm over the six-year period was more

or less than $190 million. However, one of the benefits of paying such a large sum to the CEO is that it

provides a wonderful incentive for junior managers to compete for the prize. In effect the firm runs a

tournament, in which there is a large prize for the winner and considerably smaller prizes for runners-

up. The incentive effects of tournaments show up dramatically in PGA golf tournaments. Players who

enter the final round within striking distance of big prize money perform much better than their past

records would predict. Those who receive only a small increase in prize money by moving up the rank-

ing are more inclined to relax and deliver only average performance. See R. G. Ehrenberg and M. L. Bog-

nanno, “Do Tournaments Have Incentive Effects?” Journal of Political Economy 6 (December 1990),

pp. 1307–1324.

12

See B. J. Hall and J. B. Liebman, op. cit.

13

S. Kaplan, “Top Executive Rewards and Firm Performance: A Comparison of Japan and the USA,”

Journal of Political Economy 102 (June 1994), pp. 510–546.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Almost all top executives of firms with publicly traded shares have compensation

packages that depend in part on their firms’ stock price performance. But their

compensation also depends on increases in earnings or on other accounting mea-

sures of performance. For lower-level managers, compensation packages usually

depend more on accounting measures and less on stock returns.

Accounting measures of performance have two advantages:

• They are based on absolute performance, rather than on performance relative

to investors’ expectations.

• They make it possible to measure the performance of junior managers whose

responsibility extends to only a single division or plant.

Tying compensation to accounting profits also creates some obvious problems.

First, accounting profits are partly within the control of management. For example,

managers whose pay depends on near-term earnings may cut maintenance or staff

training. This is not a recipe for adding value, but an ambitious manager hoping

for a quick promotion will be tempted to pump up short-term profits, leaving

longer-run problems to his or her successors.

Second, accounting earnings and rates of return can be severely biased mea-

sures of true profitability. We ignore this problem for now, but return to it in the

next section.

Third, growth in earnings does not necessarily mean that shareholders are

better off. Any investment with a positive rate of return (1 or 2 percent will do)

will eventually increase earnings. Therefore, if managers are told to maximize

growth in earnings, they will dutifully invest in projects offering 1 or 2 percent

rates of return—projects that destroy value. But shareholders don’t want growth

in earnings for its own sake, and they are not content with 1 or 2 percent returns.

They want positive-NPV investments, and only positive-NPV investments. They

want the company to invest only if the expected rate of return exceeds the cost

of capital.

In short, managers ought not to forget the cost of capital. In judging their per-

formance, the focus should be on value added, that is, on returns over and above

the cost of capital.

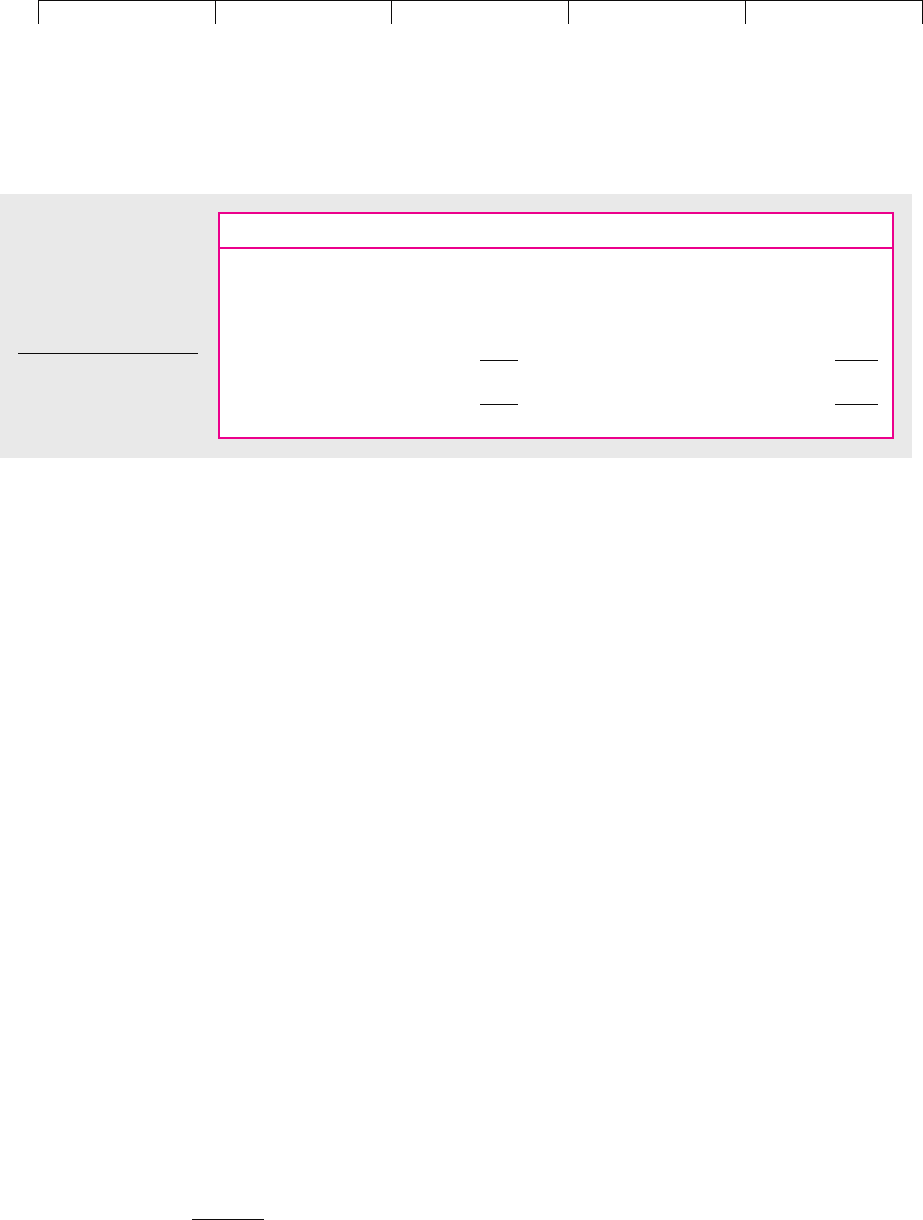

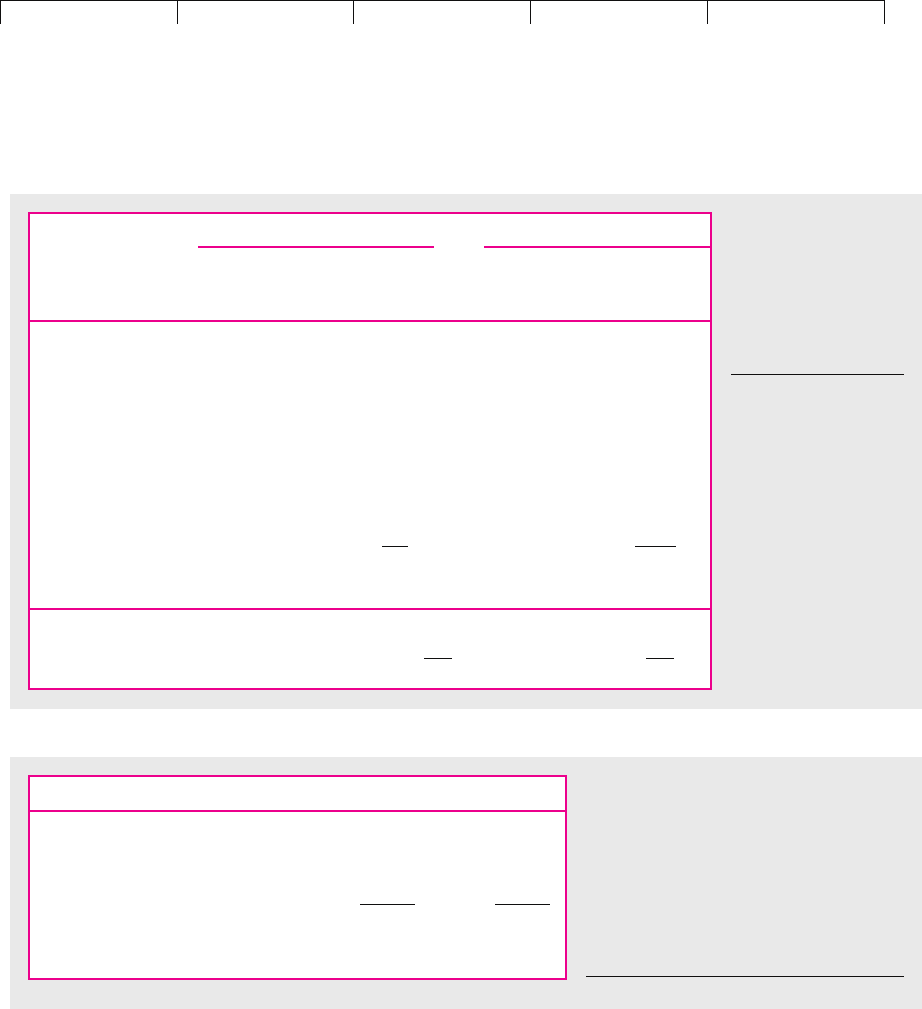

Look at Table 12.1, which contains a simplified income statement and balance

sheet for your company’s Quayle City confabulator plant. There are two methods

for judging whether the plant has increased shareholder value.

Net Return on Investment Does the return on investment exceed the cost of

capital? The net return to investment method calculates the difference be-

tween them.

As you can see from Table 12.1, your corporation has invested $1,000 million

($1 billion) in the Quayle City plant.

14

The plant’s net earnings are $130 million.

Therefore the firm is earning a return on investment (ROI) of 130/1,000 ⫽ .13 or

CHAPTER 12

Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 321

12.4 MEASURING AND REWARDING PERFORMANCE:

RESIDUAL INCOME AND EVA

14

In practice, investment would be measured as the average of beginning- and end-of-year assets. See

Chapter 29.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

13 percent.

15

If the cost of capital is (say) 10 percent, then the firm’s activities are

adding to shareholder value. The net return is 13 ⫺ 10 ⫽ 3 percent. If the cost of

capital is (say) 20 percent, then shareholders would have been better off invest-

ing $1 billion somewhere else. In this case the net return is negative, at 13 ⫺ 20 ⫽

⫺7 percent.

Residual Income or Economic Value Added (EVA ©)

16

The second method calcu-

lates a net dollar return to shareholders. It asks, What are earnings after deducting

a charge for the cost of capital?

When firms calculate income, they start with revenues and then deduct costs, such

as wages, raw material costs, overhead, and taxes. But there is one cost that they do

not commonly deduct: the cost of capital. True, they allow for depreciation of the as-

sets financed by investors’ capital, but investors also expect a positive return on their

investment. As we pointed out in Chapter 10, a business that breaks even in terms of

accounting profits is really making a loss; it is failing to cover the cost of capital.

To judge the net contribution to value, we need to deduct the cost of capital con-

tributed to the plant by the parent company and its stockholders. For example,

suppose that the cost of capital is 12 percent. Then the dollar cost of capital for the

Quayle City plant is .12 ⫻ $1,000 ⫽ $120 million. The net gain is therefore 130 ⫺

120 ⫽ $10 million. This is the addition to shareholder wealth due to management’s

hard work (or good luck).

Net income after deducting the dollar return required by investors is called

residual income, economic value added, or EVA. The formula is

For our example, the calculation is

EVA ⫽ residual income ⫽ 130 ⫺ 1.12 ⫻ 1,0002⫽⫹$10 million

⫽ income earned ⫺ cost of capital ⫻ investment

EVA ⫽ residual income ⫽ income earned ⫺ income required

322 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Income Assets

Sales $550 Net working capital

†

$80

Cost of goods sold* 275 Property, plant, and

equipment investment 1,170

Selling, general, and Less cumulative

administrative expenses 75

depreciation 360

200 Net investment 810

Taxes at 35% 70

Other assets 110

Net income $130 Total assets $1,000

TABLE 12.1

Simplified statements of

income and assets for

the Quayle City

confabulator plant

(figures in $ millions).

*

Includes depreciation

expense.

†

Current assets less current

liabilities.

15

Notice that earnings are calculated after tax but with no deductions for interest paid. The plant is

evaluated as if it were all-equity financed. This is standard practice (see Chapter 6). It helps to sepa-

rate investment and financing decisions. The tax advantages of debt financing supported by the plant

are picked up not in the plant’s earnings or cash flows but in the discount rate. The cost of capital is

the after-tax weighted average cost of capital, or WACC. WACC is explained in Chapter 19.

16

EVA is the term used by the consulting firm Stern–Stewart, which has done much to popularize and

implement this measure of residual income. With Stern–Stewart’s permission, we omit the copyright

symbol in what follows.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

But if the cost of capital were 20 percent, EVA would be negative by $70 million.

Net return on investment and EVA are focusing on the same question. When

return on investment equals the cost of capital, net return and EVA are both zero.

But the net return is a percentage and ignores the scale of the company. EVA rec-

ognizes the amount of capital employed and the number of dollars of additional

wealth created.

A growing number of firms now calculate EVA and tie management compensa-

tion to it.

17

They believe that a focus on EVA can help managers concentrate on in-

creasing shareholder wealth. One example is Quaker Oats:

Until Quaker adopted [EVA] in 1991, its businesses had one overriding goal—in-

creasing quarterly earnings. To do it, they guzzled capital. They offered sharp

price discounts at the end of each quarter, so plants ran overtime turning out huge

shipments of Gatorade, Rice-A-Roni, 100% Natural Cereal, and other products.

Managers led the late rush, since their bonuses depended on raising profits each

quarter.

This is the pernicious practice known as trade loading (because it loads up the

trade, or retailers, with product) and many consumer product companies are finally

admitting it damages long-run returns. An important reason is that it demands so

much capital. Pumping up sales requires many warehouses (capital) to hold vast

temporary inventories (more capital). But who cared? Quaker’s operating busi-

nesses paid no charge for capital in internal accounting, so they barely noticed. It

took EVA to spot the problem.

18

When Quaker Oats implemented EVA, most of the capital-guzzling stopped.

The term EVA has been popularized by the consulting firm Stern–Stewart. But

the concept of residual income has been around for some time,

19

and many com-

panies that are not Stern–Stewart clients use this concept to measure and reward

managers’ performance.

Other consulting firms have their own versions of residual income. McKinsey &

Company uses economic profit (EP), defined as capital invested multiplied by the

spread between return on investment and the cost of capital. This is another ex-

pression of the concept of residual income. For the Quayle City plant, with a 12

percent cost of capital, economic profit is the same as EVA:

Pros and Cons of EVA

Let’s start with the pros. EVA, economic profit, and other residual income mea-

sures are clearly better than earnings or earnings growth for measuring perfor-

mance. A plant or division that’s generating lots of EVA should generate accolades

⫽ 1.13 ⫺ .122⫻ 1,000 ⫽ $10 million

Economic profit ⫽ EP ⫽ 1ROI ⫺ r2⫻ capital invested

CHAPTER 12

Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 323

17

It can be shown that compensation plans that are linked to economic value added can induce a man-

ager to choose the efficient investment level. See W. P. Rogerson, “International Cost Allocation and

Managerial Incentives: A Theory Explaining the Use of Economic Value Added as a Performance Mea-

sure,” Journal of Political Economy 4 (August 1977), pp. 770–795.

18

Shawn Tully, “The Real Key to Creating Shareholder Wealth,” Fortune (September 20, 1993), p. 48.

19

EVA is conceptually the same as the residual income measure long advocated by some accounting

scholars. See, for example, R. Anthony, “Accounting for the Cost of Equity,” Harvard Business Review 51

(1973), pp. 88–102 and “Equity Interest—Its Time Has Come,” Journal of Accountancy 154 (1982),

pp. 76–93.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

for its managers as well as value for shareholders. EVA may also highlight parts of

the business that are not performing up to scratch. If a division is failing to earn a

positive EVA, its management is likely to face some pointed questions about

whether the division’s assets could be better employed elsewhere.

EVA sends a message to managers: Invest if and only if the increase in earn-

ings is enough to cover the cost of capital. For managers who are used to track-

ing earnings or growth in earnings, this is a relatively easy message to grasp.

Therefore EVA can be used down deep in the organization as an incentive com-

pensation system. It is a substitute for explicit monitoring by top management.

Instead of telling plant and divisional managers not to waste capital and then

trying to figure out whether they are complying, EVA rewards them for careful

and thoughtful investment decisions. Of course, if you tie junior managers’

compensation to their economic value added, you must also give them power

over those decisions that affect EVA. Thus the use of EVA implies delegated

decision-making.

EVA makes the cost of capital visible to operating managers. A plant manager

can improve EVA by (a) increasing earnings or (b) reducing capital employed.

Therefore underutilized assets tend to be flushed out and disposed of. Working

capital may be reduced, or at least not added to casually, as Quaker Oats did by

trade loading in its pre-EVA era. The plant managers in Quayle City may decide to

do without that cappuccino machine or extra forklift.

Introduction of residual income measures often leads to surprising reductions

in assets employed—not from one or two big capital disinvestment decisions, but

from many small ones. Ehrbar quotes a sewing machine operator at Herman Miller

Corporation:

[EVA] lets you realize that even assets have a cost. . . . we used to have these stacks

of fabric sitting here on the tables until we needed them. . . . We were going to use

the fabric anyway, so who cares that we’re buying it and stacking it up there? Now

no one has excess fabric. They only have the stuff we’re working on today. And it’s

changed the way we connect with suppliers, and we’re having [them] deliver fab-

ric more often.

20

Now we come to the first limitation to EVA. It does not involve forecasts of fu-

ture cash flows and does not measure present value. Instead, EVA depends on the

current level of earnings. It may, therefore, reward managers who take on projects

with quick paybacks and penalize those who invest in projects with long gestation

periods. Think of the difficulties in applying EVA to a pharmaceutical research pro-

gram, where it typically takes 10 to 12 years to bring a new drug from discovery to

final regulatory approval and the drug’s first revenues. That means 10 to 12 years

of guaranteed losses, even if the managers in charge do everything right. Similar

problems occur in startup ventures, where there may be heavy capital outlays but

low or negative earnings in the first years of operation. This does not imply nega-

tive NPV, so long as operating earnings and cash flows are sufficiently high later

on. But EVA would be negative in the startup years, even if the project were on

track to a strong positive NPV.

The problem in these cases lies not so much in EVA as in the measurement of in-

come. The pharmaceutical R&D program may be showing accounting losses, be-

324 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

20

A. Ehrbar, EVA: The Real Key to Creating Wealth, John Wiley & Sons, Inc., New York, 1998, pp. 130–131.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

cause generally accepted accounting principles require that outlays for R&D be

written off as a current expense. But from an economic point of view, the outlays

are an investment, not an expense. If a proposal for a new business forecasts ac-

counting losses during a startup period, but the proposal nevertheless shows pos-

itive NPV, then the startup losses are really an investment—cash outlays made to

generate larger cash inflows when the new business hits its stride.

In short, EVA and other measures of residual income depend on accurate mea-

sures of economic income and investment. Applying EVA effectively requires ma-

jor changes in income statements and balance sheets.

21

We will pick up this point

in the next section.

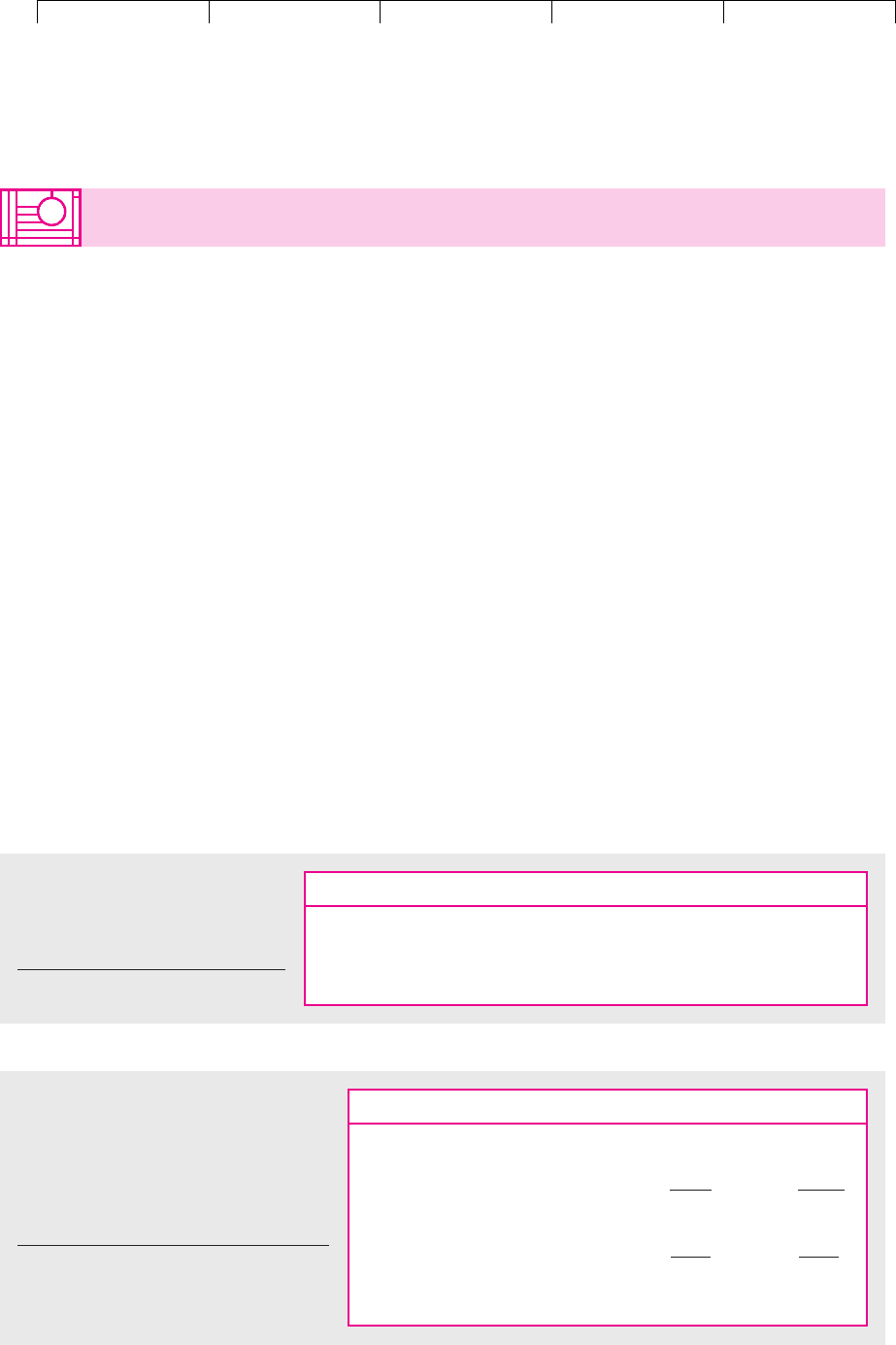

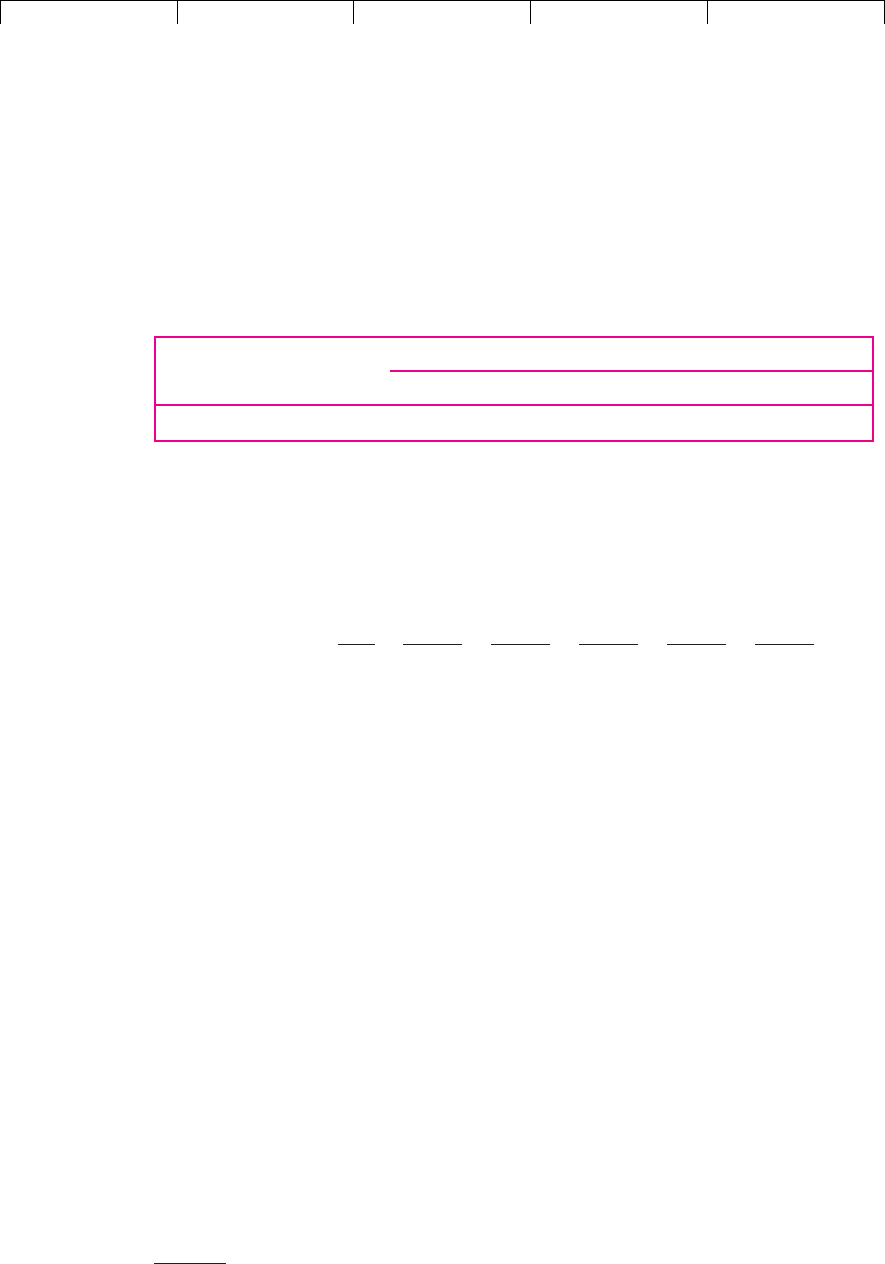

Applying EVA to Companies

EVA’s most important use is in measuring and rewarding performance inside the

firm. But it can also be applied to firms as a whole. Business periodicals regularly

report EVAs for companies and industries. Table 12.2 shows the economic value

added in 2000 for a sample of U.S. companies.

22

Notice that the firms with the

highest return on capital did not necessarily add the most economic value. For ex-

ample, Philip Morris was top of the class in terms of economic value added, but its

return on capital was less than half that of Microsoft. This is partly because Philip

Morris has more capital invested and partly because it is less risky than Microsoft

and its cost of capital is correspondingly lower.

CHAPTER 12

Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 325

21

For example, R&D should not be treated as an immediate expense but as an investment to be added

to the balance sheet and written off over a reasonable period. Eli Lilly, a large pharmaceutical company,

did this so that it could use EVA. As a result, the net value of its assets at the end of 1996 increased from

$6 to $13 billion.

22

Stern–Stewart makes some adjustments to income and assets before calculating these EVAs, but it is

almost impossible to include the value of all assets. For example, did Microsoft really earn a 39 percent

true, economic rate of return? We suspect that the value of its assets is understated. The value of its in-

tellectual property—the fruits of its investment over the years in software and operating systems—is

not shown on the balance sheet. If the denominator in a return on capital calculation is too low, the re-

sulting profitability measure is too high.

Economic

Value Added Capital Return on Cost of

(EVA) Invested Capital Capital

Philip Morris $6,081 $57,220 17.4% 6.7%

General Electric 5,943 71,421 20.4 12.1

Microsoft 5,919 23,890 39.1 14.3

Exxon Mobil 5,357 181,344 10.5 7.6

Citigroup 4,646 73,890 19.0 12.7

Coca-Cola 1,266 19,523 15.7 9.2

Boeing 94 40,651 8.0 7.8

General Motors ⫺1,065 110,111 5.7 6.7

Viacom ⫺4,370 52,045 2.0 10.4

AT&T Corp ⫺9,972 206,700 4.5 9.3

TABLE 12.2

EVA performance

of selected U.S.

companies, 2000

(dollar figures in

millions).

Note: Economic value

added is the rate of

return on capital less the

cost of capital times the

amount of capital

invested; e.g., for Coca-

Cola EVA ⫽ (.157 ⫺

.092) ⫻ 19,523 ⫽ $1,266.

Source: Data provided

by Stern–Stewart.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Any method of performance measurement that depends on accounting profitabil-

ity measures had better hope those numbers are accurate. Unfortunately they are

often not accurate, but biased. We referred to this problem in the last section and

return to it now.

Biases in Accounting Rates of Return

Business periodicals regularly report book (accounting) rates of return on invest-

ment (ROIs) for companies and industries. ROI is just the ratio of after-tax operat-

ing income to the net (depreciated) book value of assets. We rejected book ROI as

a capital investment criterion in Chapter 5, and in fact few companies now use it

for that purpose. But they do use it to evaluate profitability of existing businesses.

Consider the pharmaceutical and chemical industries. According to Table 12.3,

pharmaceutical companies have done much better than chemical companies. Are

the pharmaceutical companies really that profitable? If so, lots of companies should

be rushing into the pharmaceutical business. Or is there something wrong with the

ROI measure?

Pharmaceutical companies have done well, but they look more profitable than

they really are. Book ROIs are biased upward for companies with intangible in-

vestments such as R&D, simply because accountants don’t put these outlays on the

balance sheet.

Table 12.4 shows cash inflows and outflows for two mature companies. Neither

is growing. Each must plow back $400 million to maintain its existing business. The

only difference is that the chemical company’s plowback goes mostly to plant and

326 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

12.5 BIASES IN ACCOUNTING MEASURES

OF PERFORMANCE

Pharmaceutical Chemical

Abbot Laboratories 19.2% Du Pont 7.3%

Bristol-Myers Squibb 24.0 Dow Chemical 7.5

Merck 19.7 Ethyl Corporation 8.5

Pfizer 14.9 Hercules Inc. 5.4

TABLE 12.3

After-tax accounting rates of return

for pharmaceutical and chemical

companies, 2000.

Source: Datastream.

Pharmaceutical Chemical

Revenues 1,000 1,000

Operating costs, out-of-pocket* 500 500

Net operating cash flow 500

500

Investment in:

Plant and equipment 100 300

R&D 300 100

Total investment 400 400

Annual cash flow

†

⫹100 ⫹100

TABLE 12.4

Comparison of a pharmaceutical company

and a chemical company, each in a no-growth

steady state (figures in $ millions). Revenues,

costs, total investment, and annual cash flow

are identical. But the pharmaceutical company

invests more in R&D.

*Operating costs do not include any charge for

depreciation.

†

Cash flow ⫽ revenues ⫺ operating costs ⫺ total

investment.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

equipment; the pharmaceutical company invests mostly in R&D. The chemical

company invests only one-third as much in R&D ($100 versus $300 million) but

triples the pharmaceutical company’s investment in fixed assets.

Table 12.5 calculates the annual depreciation charges. Notice that the sum of

R&D and total annual depreciation is identical for the two companies.

The companies’ cash flows, true profitability, and true present values are also

identical, but as Table 12.6 shows, the pharmaceutical company’s book ROI is 18

percent, triple the chemical company’s. The accountants would get annual income

right (in this case it is identical to cash flow) but understate the value of the phar-

maceutical company’s assets relative to the chemical company’s. Lower asset value

creates the upward-biased pharmaceutical ROI.

The first moral is this: Do not assume that businesses with high book ROIs are

necessarily performing better. They may just have more hidden assets, that is, as-

sets which accountants do not put on balance sheets.

CHAPTER 12

Making Sure Managers Maximize NPV 327

Pharmaceutical Chemical

Original

Age, Original Cost Net Book Cost of Net Book

Years of Investment Value Investment Value

0 (new) 100 100 300 300

1 100 90 300 270

2 100 80 300 240

3 100 70 300 210

4 100 60 300 180

5 100 50 300 150

6 100 40 300 120

7 100 30 300 90

8 100 20 300 60

9 100 10 300 30

Total net book value 550 1,650

Pharmaceutical Chemical

Annual depreciation* 100 300

R&D expense 300 100

Total depreciation and R&D 400 400

TABLE 12.5

Book asset values and

annual depreciation for

the pharmaceutical and

chemical companies

described in Table 12.4

(figures in $ millions).

*The pharmaceutical

company has 10 vintages

of assets, each

depreciated by $10 per

year. Total depreciation

per year is 10 ⫻ 10 ⫽ $100

million. The chemical

company’s depreciation is

10 ⫻ 30 ⫽ $300 million.

Pharmaceutical Chemical

Revenues 1,000 1,000

Operating costs, out-of-pocket 500 500

R&D expense 300 100

Depreciation* 100 300

Net income 100 100

Net book value* 550 1,650

Book ROI 18% 6%

TABLE 12.6

Book ROIs for the companies described in

Table 12.4 (figures in $ millions). The

chemical and pharmaceutical companies’

cash flows and values are identical. But the

pharmaceutical’s accounting rate of return

is triple the chemical’s. This bias occurs

because accountants do not show the value

of investment in R&D on the balance sheet.

*Calculated in Table 12.5.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

III. Practical Problems in

Capital Budgeting

12.Making Sure Managers

Maximize NPV

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Measuring the Profitability of the Nodhead Supermarket—

Another Example

Supermarket chains invest heavily in building and equipping new stores. The re-

gional manager of a chain is about to propose investing $1 million in a new store

in Nodhead. Projected cash flows are

328 PART III

Practical Problems in Capital Budgeting

Year

123456after 6

Cash flow ($ thousands) 100 200 250 298 298 298 0

Of course, real supermarkets last more than six years. But these numbers are real-

istic in one important sense: It may take two or three years for a new store to catch

on—that is, to build up a substantial, habitual clientele. Thus cash flow is low for

the first few years even in the best locations.

We will assume the opportunity cost of capital is 10 percent. The Nodhead store’s

NPV at 10 percent is zero. It is an acceptable project, but not an unusually good one:

With NPV ⫽ 0, the true (internal) rate of return of this cash-flow stream is also 10

percent.

Table 12.7 shows the store’s forecasted book profitability, assuming straight-line

depreciation over its six-year life. The book ROI is lower than the true return for

the first two years and higher afterward.

23

This is the typical outcome: Accounting

profitability measures are too low when a project or business is young and are too

high as it matures.

At this point the regional manager steps up on stage for the following soliloquy:

The Nodhead store’s a decent investment. I really should propose it. But if we go

ahead, I won’t look very good at next year’s performance review. And what if I also

go ahead with the new stores in Russet, Gravenstein, and Sheepnose? Their cash-flow

patterns are pretty much the same. I could actually appear to lose money next year.

The stores I’ve got won’t earn enough to cover the initial losses on four new ones.

Of course, everyone knows new supermarkets lose money at first. The loss

would be in the budget. My boss will understand—I think. But what about her

boss? What if the board of directors starts asking pointed questions about prof-

itability in my region? I’m under a lot of pressure to generate better earnings.

Pamela Quince, the upstate manager, got a bonus for generating a 40 percent in-

crease in book ROI. She didn’t spend much on expansion.

The regional manager is getting conflicting signals. On one hand, he is told to

find and propose good investment projects. Good is defined by discounted cash

flow. On the other hand, he is also urged to increase book earnings. But the two

goals conflict because book earnings do not measure true earnings. The greater the

NPV ⫽⫺1,000 ⫹

100

1.10

⫹

200

11.102

2

⫹

250

11.102

3

⫹

298

11.102

4

⫹

298

11.102

5

⫹

298

11.102

6

⫽ 0

23

The errors in book ROI always catch up with you in the end. If the firm chooses a depreciation sched-

ule that overstates a project’s return in some years, it must also understate the return in other years. In

fact, you can think of a project’s IRR as a kind of average of the book returns. It is not a simple average,

however. The weights are the project’s book values discounted at the IRR. See J. A. Kay, “Accountants,

Too, Could Be Happy in a Golden Age: The Accountant’s Rate of Profit and the Internal Rate of Return,”

Oxford Economic Papers 28 (1976), pp. 447–460.