Brealey, Myers. Principles of Corporate Finance. 7th edition

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Not all investments are equally risky. The office development is more risky

than a government security but less risky than a start-up biotech venture. Suppose

you believe the project is as risky as investment in the stock market and that stock

market investments are forecasted to return 12 percent. Then 12 percent becomes

the appropriate opportunity cost of capital. That is what you are giving up by not

investing in equally risky securities. Now recompute NPV:

NPV PV 350,000 $7,143

If other investors agree with your forecast of a $400,000 payoff and your assess-

ment of its risk, then your property ought to be worth $357,143 once construction

is underway. If you tried to sell it for more, there would be no takers, because the

property would then offer an expected rate of return lower than the 12 percent

available in the stock market. The office building still makes a net contribution to

value, but it is much smaller than our earlier calculations indicated.

The value of the office building depends on the timing of the cash flows and

their uncertainty. The $400,000 payoff would be worth exactly that if it could be

realized instantaneously. If the office building is as risk-free as government se-

curities, the one-year delay reduces value to $373,832. If the building is as risky

as investment in the stock market, then uncertainty further reduces value by

$16,689 to $357,143.

Unfortunately, adjusting asset values for time and uncertainty is often more

complicated than our example suggests. Therefore, we will take the two effects

separately. For the most part, we will dodge the problem of risk in Chapters 2

through 6, either by treating all cash flows as if they were known with certainty or

by talking about expected cash flows and expected rates of return without worry-

ing how risk is defined or measured. Then in Chapter 7 we will turn to the prob-

lem of understanding how financial markets cope with risk.

Present Values and Rates of Return

We have decided that construction of the office building is a smart thing to do,

since it is worth more than it costs—it has a positive net present value. To calcu-

late how much it is worth, we worked out how much one would need to pay to

achieve the same payoff by investing directly in securities. The project’s present

value is equal to its future income discounted at the rate of return offered by

these securities.

We can say this in another way: Our property venture is worth undertaking

because its rate of return exceeds the cost of capital. The rate of return on the in-

vestment in the office building is simply the profit as a proportion of the initial

outlay:

The cost of capital is once again the return foregone by not investing in securities.

If the office building is as risky as investing in the stock market, the return foregone

is 12 percent. Since the 14 percent return on the office building exceeds the 12 per-

cent opportunity cost, you should go ahead with the project.

Return

profit

investment

400,000 350,000

350,000

.143, about 14%

PV

400,000

1.12

$357,143

16 PART I Value

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Here then we have two equivalent decision rules for capital investment:

4

• Net present value rule. Accept investments that have positive net present values.

• Rate-of-return rule. Accept investments that offer rates of return in excess of

their opportunity costs of capital.

5

The Opportunity Cost of Capital

The opportunity cost of capital is such an important concept that we will give one

more example. You are offered the following opportunity: Invest $100,000 today,

and, depending on the state of the economy at the end of the year, you will receive

one of the following payoffs:

CHAPTER 2

Present Value and the Opportunity Cost of Capital 17

4

You might check for yourself that these are equivalent rules. In other words, if the return

50,000/350,000 is greater than r, then the net present value 350,000 [400,000/(1 r)] must be greater

than 0.

5

The two rules can conflict when there are cash flows in more than two periods. We address this prob-

lem in Chapter 5.

6

We are assuming that the probabilities of slump and boom are equal, so that the expected (average)

outcome is $110,000. For example, suppose the slump, normal, and boom probabilities are all 1/3. Then

the expected payoff C

1

(80,000 110,000 140,000)/3 $110.000.

Slump Normal Boom

$80,000 $110,000 $140,000

You reject the optimistic (boom) and the pessimistic (slump) forecasts. That gives

an expected payoff of C

1

110,000,

6

a 10 percent return on the $100,000 investment.

But what’s the right discount rate?

You search for a common stock with the same risk as the investment. Stock X

turns out to be a perfect match. X’s price next year, given a normal economy, is fore-

casted at $110. The stock price will be higher in a boom and lower in a slump, but

to the same degrees as your investment ($140 in a boom and $80 in a slump). You

conclude that the risks of stock X and your investment are identical.

Stock X’s current price is $95.65. It offers an expected rate of return of 15 percent:

This is the expected return that you are giving up by investing in the project rather

than the stock market. In other words, it is the project’s opportunity cost of capital.

To value the project, discount the expected cash flow by the opportunity cost of

capital:

This is the amount it would cost investors in the stock market to buy an expected cash

flow of $110,000. (They could do so by buying 1,000 shares of stock X.) It is, therefore,

also the sum that investors would be prepared to pay you for your project.

To calculate net present value, deduct the initial investment:

NPV 95,650 100,000 $4,350

PV

110,000

1.15

$95,650

Expected return

expected profit

investment

110 95.65

95.65

.15, or 15%

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

The project is worth $4,350 less than it costs. It is not worth undertaking.

Notice that you come to the same conclusion if you compare the expected proj-

ect return with the cost of capital:

The 10 percent expected return on the project is less than the 15 percent return in-

vestors could expect to earn by investing in the stock market, so the project is not

worthwhile.

Of course in real life it’s impossible to restrict the future states of the economy

to just “slump,” “normal,” and “boom.” We have also simplified by assuming a

perfect match between the payoffs of 1,000 shares of stock X and the payoffs to the

investment project. The main point of the example does carry through to real life,

however. Remember this: The opportunity cost of capital for an investment project

is the expected rate of return demanded by investors in common stocks or other se-

curities subject to the same risks as the project. When you discount the project’s ex-

pected cash flow at its opportunity cost of capital, the resulting present value is the

amount investors (including your own company’s shareholders) would be willing

to pay for the project. Any time you find and launch a positive-NPV project (a proj-

ect with present value exceeding its required cash outlay) you have made your

company’s stockholders better off.

A Source of Confusion

Here is a possible source of confusion. Suppose a banker approaches. “Your company

is a fine and safe business with few debts,” she says. “My bank will lend you the

$100,000 that you need for the project at 8 percent.” Does that mean that the cost of

capital for the project is 8 percent? If so, the project would be above water, with PV at

8 percent 110,000/1.08 $101,852 and NPV 101,852 100,000 $1,852.

That can’t be right. First, the interest rate on the loan has nothing to do with the risk

of the project: It reflects the good health of your existing business. Second, whether you

take the loan or not, you still face the choice between the project, which offers an ex-

pected return of only 10 percent, or the equally risky stock, which gives an expected

return of 15 percent. A financial manager who borrows at 8 percent and invests at

10 percent is not smart, but stupid, if the company or its shareholders can borrow at

8 percent and buy an equally risky investment offering 15 percent. That is why the

15 percent expected return on the stock is the opportunity cost of capital for the project.

110,000 100,000

100,000

.10, or 10%

Expected return on project

expected profit

investment

18 PART I Value

2.2 FOUNDATIONS OF THE NET PRESENT VALUE

RULE

So far our discussion of net present value has been rather casual. Increasing value

sounds like a sensible objective for a company, but it is more than just a rule of

thumb. You need to understand why the NPV rule makes sense and why managers

look to the bond and stock markets to find the opportunity cost of capital.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

In the previous example there was just one person (you) making 100 percent of

the investment and receiving 100 percent of the payoffs from the new office build-

ing. In corporations, investments are made on behalf of thousands of shareholders

with varying risk tolerances and preferences for present versus future income.

Could a positive-NPV project for Ms. Smith be a negative-NPV proposition for Mr.

Jones? Could they find it impossible to agree on the objective of maximizing the

market value of the firm?

The answer to both questions is no; Smith and Jones will always agree if both have

access to capital markets. We will demonstrate this result with a simple example.

How Capital Markets Reconcile Preferences for Current

vs. Future Consumption

Suppose that you can look forward to a stream of income from your job. Unless you

have some way of storing or anticipating this income, you will be compelled to con-

sume it as it arrives. This could be inconvenient or worse. If the bulk of your income

comes late in life, the result could be hunger now and gluttony later. This is where the

capital market comes in. The capital market allows trade between dollars today and

dollars in the future. You can therefore eat moderately both now and in the future.

We will now illustrate how the existence of a well-functioning capital market

allows investors with different time patterns of income and desired consump-

tion to agree on whether investment projects should be undertaken. Suppose

that there are two investors with different preferences. A is an ant, who wishes

to save for the future; G is a grasshopper, who would prefer to spend all his

wealth on some ephemeral frolic, taking no heed of tomorrow. Now suppose

that each is confronted with an identical opportunity—to buy a share in a

$350,000 office building that will produce a sure-fire $400,000 at the end of the

year, a return of about 14 percent. The interest rate is 7 percent. A and G can bor-

row or lend in the capital market at this rate.

A would clearly be happy to invest in the office building. Every hundred dollars

that she invests in the office building allows her to spend $114 at the end of the year,

while a hundred dollars invested in the capital market would enable her to spend

only $107.

But what about G, who wants money now, not in one year’s time? Would he pre-

fer to forego the investment opportunity and spend today the cash that he has in

hand? Not as long as the capital market allows individuals to borrow as well as to

lend. Every hundred dollars that G invests in the office building brings in $114 at

the end of the year. Any bank, knowing that G could look forward to this sure-fire

income, would be prepared to lend him $114/1.07 $106.54 today. Thus, instead

of spending $100 today, G can spend $106.54 if he invests in the office building and

then borrows against his future income.

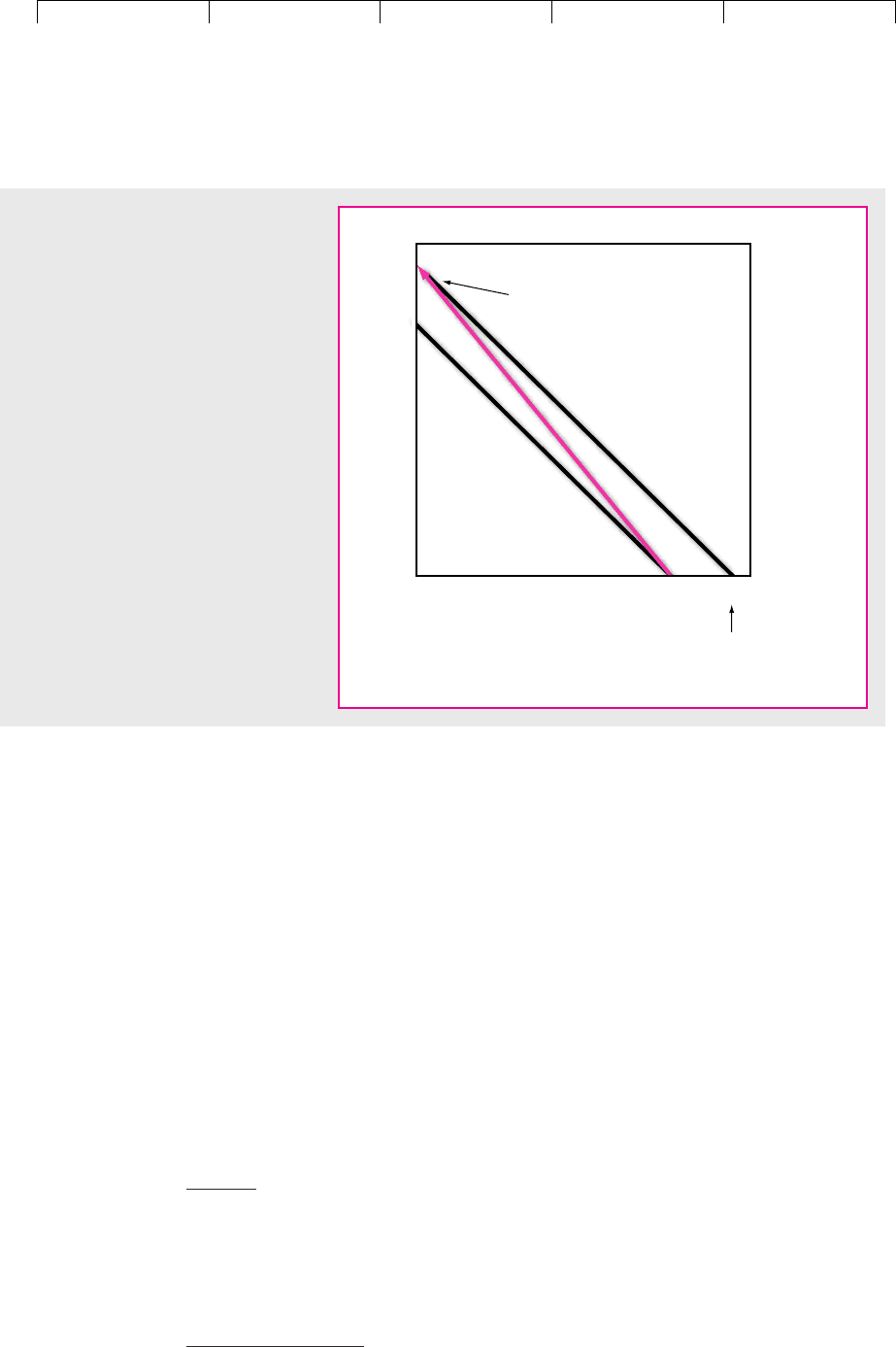

This is illustrated in Figure 2.1. The horizontal axis shows the number of dol-

lars that can be spent today; the vertical axis shows spending next year. Suppose

that the ant and the grasshopper both start with an initial sum of $100. If they

invest the entire $100 in the capital market, they will be able to spend 100 1.07

$107 at the end of the year. The straight line joining these two points (the in-

nermost line in the figure) shows the combinations of current and future con-

sumption that can be achieved by investing none, part, or all of the cash at the

7 percent rate offered in the capital market. (The interest rate determines the

slope of this line.) Any other point along the line could be achieved by spending

CHAPTER 2

Present Value and the Opportunity Cost of Capital 19

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

part of the $100 today and investing the balance.

7

For example, one could choose

to spend $50 today and $53.50 next year. However, A and G would each reject

such a balanced consumption schedule.

The burgundy arrow in Figure 2.1 shows the payoff to investing $100 in a share

of your office project. The rate of return is 14 percent, so $100 today transmutes to

$114 next year.

The sloping line on the right in Figure 2.1 (the outermost line in the figure)

shows how A’s and G’s spending plans are enhanced if they can choose to invest

their $100 in the office building. A, who is content to spend nothing today, can in-

vest $100 in the building and spend $114 at the end of the year. G, the spendthrift,

also invests $100 in the office building but borrows 114/1.07 $106.54 against the

future income. Of course, neither is limited to these spending plans. In fact, the

right-hand sloping line shows all the combinations of current and future expendi-

ture that an investor could achieve from investing $100 in the office building and

borrowing against some fraction of the future income.

You can see from Figure 2.1 that the present value of A’s and G’s share in the

office building is $106.54. The net present value is $6.54. This is the distance be-

20 PART I

Value

7

The exact balance between present and future consumption that each individual will choose depends

on personal preferences. Readers who are familiar with economic theory will recognize that the choice

can be represented by superimposing an indifference map for each individual. The preferred combina-

tion is the point of tangency between the interest-rate line and the individual’s indifference curve. In

other words, each individual will borrow or lend until 1 plus the interest rate equals the marginal rate

of time preference (i.e., the slope of the indifference curve). A more formal graphical analysis of invest-

ment and the choice between present and future consumption is on the Brealey–Myers website at

www://mhhe.com/bm/7e.

Dollars now

A

invests $100 in office

building and consumes $114

next year.

106.54

114

107

Dollars next year

G

invests $100 in office

building, borrows $106.54, and

consumes that amount now.

100

FIGURE 2.1

The grasshopper (G) wants consumption

now. The ant (A) wants to wait. But each

is happy to invest. A prefers to invest at

14 percent, moving up the burgundy arrow,

rather than at the 7 percent interest rate.

G invests and then borrows at 7 percent,

thereby transforming $100 into $106.54 of

immediate consumption. Because of the

investment, G has $114 next year to pay

off the loan. The investment’s NPV is

106.54 100 6.54.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

tween the $106.54 present value and the $100 initial investment. Despite their dif-

ferent tastes, both A and G are better off by investing in the office block and then

using the capital markets to achieve the desired balance between consumption

today and consumption at the end of the year. In fact, in coming to their invest-

ment decision, both would be happy to follow the two equivalent rules that we

proposed so casually at the end of Section 2.1. The two rules can be restated as

follows:

• Net present value rule. Invest in any project with a positive net present value.

This is the difference between the discounted, or present, value of the future

cash flow and the amount of the initial investment.

• Rate-of-return rule. Invest as long as the return on the investment exceeds the

rate of return on equivalent investments in the capital market.

What happens if the interest rate is not 7 percent but 14.3 percent? In this case

the office building would have zero NPV:

NPV 400,000/1.143 350,000 $0

Also, the return on the project would be 400,000/350,000 1 .143, or 14.3 per-

cent, exactly equal to the rate of interest in the capital market. In this case our two

rules would say that the project is on a knife edge. Investors should not care

whether the firm undertakes it or not.

It is easy to see that with a 14.3 percent interest rate neither A nor G would gain

anything by investing in the office building. A could spend exactly the same

amount at the end of the year, regardless of whether she invests her money in the

office building or in the capital market. Equally, there is no advantage in G in-

vesting in an office block to earn 14.3 percent and at the same time borrowing at

14.3 percent. He might just as well spend whatever cash he has on hand.

In our example the ant and the grasshopper placed an identical value on the of-

fice building and were happy to share in its construction. They agreed because they

faced identical borrowing and lending opportunities. Whenever firms discount

cash flows at capital market rates, they are implicitly assuming that their share-

holders have free and equal access to competitive capital markets.

It is easy to see how our net present value rule would be damaged if we did

not have such a well-functioning capital market. For example, suppose that G

could not borrow against future income or that it was prohibitively costly for

him to do so. In that case he might well prefer to spend his cash today rather

than invest it in an office building and have to wait until the end of the year be-

fore he could start spending. If A and G were shareholders in the same enter-

prise, there would be no simple way for the manager to reconcile their different

objectives.

No one believes unreservedly that capital markets are perfectly competitive.

Later in this book we will discuss several cases in which differences in taxation,

transaction costs, and other imperfections must be taken into account in financial

decision making. However, we will also discuss research which indicates that, in

general, capital markets function fairly well. That is one good reason for relying on

net present value as a corporate objective. Another good reason is that net present

value makes common sense; we will see that it gives obviously silly answers less

frequently than its major competitors. But for now, having glimpsed the problems

of imperfect markets, we shall, like an economist in a shipwreck, simply assume our

life jacket and swim safely to shore.

CHAPTER 2

Present Value and the Opportunity Cost of Capital 21

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

Our justification of the present value rule was restricted to two periods and to a

certain cash flow. However, the rule also makes sense for uncertain cash flows that

extend far into the future. The argument goes like this:

1. A financial manager should act in the interests of the firm’s owners, its

stockholders. Each stockholder wants three things:

a. To be as rich as possible, that is, to maximize current wealth.

b. To transform that wealth into whatever time pattern of consumption he

or she desires.

c. To choose the risk characteristics of that consumption plan.

2. But stockholders do not need the financial manager’s help to achieve the

best time pattern of consumption. They can do that on their own, providing

they have free access to competitive capital markets. They can also choose

the risk characteristics of their consumption plan by investing in more or

less risky securities.

3. How then can the financial manager help the firm’s stockholders? There is

only one way: by increasing the market value of each stockholder’s stake in

the firm. The way to do that is to seize all investment opportunities that

have a positive net present value.

Despite the fact that shareholders have different preferences, they are unani-

mous in the amount that they want to invest in real assets. This means that they

can cooperate in the same enterprise and can safely delegate operation of that en-

terprise to professional managers. These managers do not need to know anything

about the tastes of their shareholders and should not consult their own tastes. Their

task is to maximize net present value. If they succeed, they can rest assured that

they have acted in the best interest of their shareholders.

This gives us the fundamental condition for successful operation of a modern

capitalist economy. Separation of ownership and control is essential for most cor-

porations, so authority to manage has to be delegated. It is good to know that man-

agers can all be given one simple instruction: Maximize net present value.

Other Corporate Goals

Sometimes you hear managers speak as if the corporation has other goals. For ex-

ample, they may say that their job is to maximize profits. That sounds reasonable.

After all, don’t shareholders prefer to own a profitable company rather than an un-

profitable one? But taken literally, profit maximization doesn’t make sense as a cor-

porate objective. Here are three reasons:

1. “Maximizing profits” leaves open the question, Which year’s profits?

Shareholders might not want a manager to increase next year’s profits at

the expense of profits in later years.

2. A company may be able to increase future profits by cutting its dividend

and investing the cash. That is not in the shareholders’ interest if the

company earns only a low return on the investment.

3. Different accountants may calculate profits in different ways. So you may

find that a decision which improves profits in one accountant’s eyes will

reduce them in the eyes of another.

22 PART I

Value

2.3 A FUNDAMENTAL RESULT

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

We have explained that managers can best serve the interests of shareholders by

investing in projects with a positive net present value. But this takes us back to the

principal–agent problem highlighted in the first chapter. How can shareholders

(the principals) ensure that management (their agents) don’t simply look after their

own interests? Shareholders can’t spend their lives watching managers to check

that they are not shirking or maximizing the value of their own wealth. However,

there are several institutional arrangements that help to ensure that the sharehold-

ers’ pockets are close to the managers’ heart.

A company’s board of directors is elected by the shareholders and is supposed

to represent them. Boards of directors are sometimes portrayed as passive

stooges who always champion the incumbent management. But when company

performance starts to slide and managers do not offer a credible recovery plan,

boards do act. In recent years the chief executives of Eastman Kodak, General

Motors, Xerox, Lucent, Ford Motor, Sunbeam, and Lands End were all forced to

step aside when each company’s profitability deteriorated and the need for new

strategies became clear.

If shareholders believe that the corporation is underperforming and that the

board of directors is not sufficiently aggressive in holding the managers to task,

they can try to replace the board in the next election. If they succeed, the new board

will appoint a new management team. But these attempts to vote in a new board

are expensive and rarely successful. Thus dissidents do not usually stand and fight

but sell their shares instead.

Selling, however, can send a powerful message. If enough shareholders bail out,

the stock price tumbles. This damages top management’s reputation and compen-

sation. Part of the top managers’ paychecks comes from bonuses tied to the com-

pany’s earnings or from stock options, which pay off if the stock price rises but are

worthless if the price falls below a stated threshold. This should motivate man-

agers to increase earnings and the stock price.

If managers and directors do not maximize value, there is always the threat

of a hostile takeover. The further a company’s stock price falls, due to lax man-

agement or wrong-headed policies, the easier it is for another company or

group of investors to buy up a majority of the shares. The old management team

is then likely to find themselves out on the street and their place is taken by a

fresh team prepared to make the changes needed to realize the company’s

value.

These arrangements ensure that few managers at the top of major United States

corporations are lazy or inattentive to stockholders’ interests. On the contrary, the

pressure to perform can be intense.

CHAPTER 2

Present Value and the Opportunity Cost of Capital 23

2.4 DO MANAGERS REALLY LOOK AFTER

THE INTERESTS OF SHAREHOLDERS?

2.5 SHOULD MANAGERS LOOK AFTER THE INTERESTS

OF SHAREHOLDERS?

We have described managers as the agents of the shareholders. But perhaps this

begs the question, Is it desirable for managers to act in the selfish interests of their

shareholders? Does a focus on enriching the shareholders mean that managers

must act as greedy mercenaries riding roughshod over the weak and helpless? Do

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

they not have wider obligations to their employees, customers, suppliers, and the

communities in which the firm is located?

8

Most of this book is devoted to financial policies that increase a firm’s value.

None of these policies requires gallops over the weak and helpless. In most in-

stances there is little conflict between doing well (maximizing value) and doing

good. Profitable firms are those with satisfied customers and loyal employees;

firms with dissatisfied customers and a disgruntled workforce are more likely to

have declining profits and a low share price.

Of course, ethical issues do arise in business as in other walks of life, and there-

fore when we say that the objective of the firm is to maximize shareholder wealth,

we do not mean that anything goes. In part, the law deters managers from making

blatantly dishonest decisions, but most managers are not simply concerned with

observing the letter of the law or with keeping to written contracts. In business and

finance, as in other day-to-day affairs, there are unwritten, implicit rules of behav-

ior. To work efficiently together, we need to trust each other. Thus huge financial

deals are regularly completed on a handshake, and each side knows that the other

will not renege later if things turn sour.

9

Whenever anything happens to weaken

this trust, we are all a little worse off.

10

In many financial transactions, one party has more information than the other.

It can be difficult to be sure of the quality of the asset or service that you are buy-

ing. This opens up plenty of opportunities for financial sharp practice and outright

fraud, and, because the activities of scoundrels are more entertaining than those of

honest people, airport bookstores are packed with accounts of financial fraudsters.

The response of honest firms is to distinguish themselves by building long-term

relationships with their customers and establishing a name for fair dealing and fi-

nancial integrity. Major banks and securities firms know that their most valuable

asset is their reputation. They emphasize their long history and responsible be-

havior. When something happens to undermine that reputation, the costs can be

enormous.

Consider the Salomon Brothers bidding scandal in 1991.

11

A Salomon trader

tried to evade rules limiting the firm’s participation in auctions of U.S. Treasury

bonds by submitting bids in the names of the company’s customers without the

customers’ knowledge. When this was discovered, Salomon settled the case by

paying almost $200 million in fines and establishing a $100 million fund for pay-

ments of claims from civil lawsuits. Yet the value of Salomon Brothers stock fell by

24 PART I

Value

8

Some managers, anxious not to offend any group of stakeholders, have denied that they are maximiz-

ing profits or value. We are reminded of a survey of businesspeople that inquired whether they at-

tempted to maximize profits. They indignantly rejected the notion, objecting that their responsibilities

went far beyond the narrow, selfish profit motive. But when the question was reformulated and they

were asked whether they could increase profits by raising or lowering their selling price, they replied

that neither change would do so. The survey is cited in G. J. Stigler, The Theory of Price, 3rd ed. (New

York: Macmillan Company, 1966).

9

In U.S. law, a contract can be valid even if it is not written down. Of course documentation is prudent,

but contracts are enforced if it can be shown that the parties reached a clear understanding and agree-

ment. For example, in 1984, the top management of Getty Oil gave verbal agreement to a merger offer

with Pennzoil. Then Texaco arrived with a higher bid and won the prize. Pennzoil sued—and won—

arguing that Texaco had broken up a valid contract.

10

For a discussion of this issue, see A. Schleifer and L. H. Summers, “Breach of Trust in Corporate

Takeovers,” Corporate Takeovers: Causes and Consequences (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988).

11

This discussion is based on Clifford W. Smith, Jr., “Economics and Ethics: The Case of Salomon Broth-

ers,” Journal of Applied Corporate Finance 5 (Summer 1992), pp. 23–28.

Brealey−Meyers:

Principles of Corporate

Finance, Seventh Edition

I. Value 2. Present Value and the

Opportunity Cost of Capital

© The McGraw−Hill

Companies, 2003

CHAPTER 2 Present Value and the Opportunity Cost of Capital 25

far more than $300 million. In fact the price dropped by about a third, representing

a $1.5 billion decline in the company’s market value.

Why did the value of Salomon Brothers drop so dramatically? Largely because

investors were worried that Salomon would lose business from customers that

now distrusted the company. The damage to Salomon’s reputation was far greater

than the explicit costs of the scandal and was hundreds or thousands of times more

costly than the potential gains Salomon could have reaped from the illegal trades.

SUMMARY

In this chapter we have introduced the concept of present value as a way of valu-

ing assets. Calculating present value is easy. Just discount future cash flow by an

appropriate rate r, usually called the opportunity cost of capital, or hurdle rate:

Net present value is present value plus any immediate cash flow:

Remember that C

0

is negative if the immediate cash flow is an investment, that is,

if it is a cash outflow.

The discount rate is determined by rates of return prevailing in capital markets.

If the future cash flow is absolutely safe, then the discount rate is the interest rate

on safe securities such as United States government debt. If the size of the future

cash flow is uncertain, then the expected cash flow should be discounted at the ex-

pected rate of return offered by equivalent-risk securities. We will talk more about

risk and the cost of capital in Chapters 7 through 9.

Cash flows are discounted for two simple reasons: first, because a dollar today

is worth more than a dollar tomorrow, and second, because a safe dollar is worth

more than a risky one. Formulas for PV and NPV are numerical expressions of

these ideas. The capital market is the market where safe and risky future cash flows

are traded. That is why we look to rates of return prevailing in the capital markets

to determine how much to discount for time and risk. By calculating the present

value of an asset, we are in effect estimating how much people will pay for it if they

have the alternative of investing in the capital markets.

The concept of net present value allows efficient separation of ownership and

management of the corporation. A manager who invests only in assets with pos-

itive net present values serves the best interests of each one of the firm’s owners,

regardless of differences in their wealth and tastes. This is made possible by the

existence of the capital market which allows each shareholder to construct a per-

sonal investment plan that is custom tailored to his or her own requirements. For

example, there is no need for the firm to arrange its investment policy to obtain

a sequence of cash flows that matches its shareholders’ preferred time patterns

of consumption. The shareholders can shift funds forward or back over time per-

fectly well on their own, provided they have free access to competitive capital

markets. In fact, their plan for consumption over time is limited by only two

things: their personal wealth (or lack of it) and the interest rate at which they can

borrow or lend. The financial manager cannot affect the interest rate but can

Net present value 1NPV2 C

0

C

1

1 r

Present value 1PV2

C

1

1 r

Visit us at www.mhhe.com/bm7e