Bradbury Jim. The Routledge Companion to Medieval Warfare

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

with two globular decorations. The

basilard

was a type of dagger with a blade broad at

the hilt, popular in Italy. A dagger with an even broader blade at the hilt was the ox-

tongue or

cinquedea

—five fingers in width. A common 15th-century dagger was the

rondel,

with discs at either end of the hilt, a slim, needle-like weapon. In the Renaissance

period it was common to fight with sword in one hand, dagger in the other.

FALCHION

Sword with a curved, sharp outer edge broadening towards the point and then tapering

so that it looked boat-shaped. The blunt edge was straight. The name was from Latin

falx

(scythe) from its shape. It descended from the Norse seax. Its period of prominence was

the 13th and 14th centuries. The

faussar

of 12th-century Iberia might be an early

example. The falchion was used by lower ranking infantry, men-at-arms and archers. One

was found at the Châtelet in Paris with the Grand Châtelet arms on the pommel. The

Conyers Falchion, at Durham, was used in tenure ceremonies.

FIREARMS

The medieval period saw the introduction to Europe of gunpowder and firearms.

Experiments with gunpowder occurred in the 13th century. Initially used for portable

artillery weapons, these inspired the invention of handguns. A culverin could be mounted

on a tripod or used by hand, like the culverins

ad manum

mentioned in 1435. Early

firearms were inefficient but by the late Middle Ages their value was clear. The

Anatolian Turks had handguns in the mid-14th century, but guns developed faster in the

west. By the 16th century the Turks regained the initiative. In 1364 Italians produced

small handguns in Perugia and Modena. There is a record in England from c.1375 for the

fitting of eight guns with handles like pikes. The term handgun first appeared in 1386.

Handguns were more common by the 15th century, in the Hundred Years’ War and the

Hussite Wars. At Caravaggio, Italy, in 1448 the smoke from Milanese handguns obscured

the view. In that year Hungarian handgunners defeated the Ottomans under Murad II.

Flemings and Germans were noted for supplying handgunners. Musketeers became

significant in the early modern period.

FRANCISKA (FRANCISCA)

Small throwing axe associated with the Franks, named after them or they after it. The

word is the Latin term found in chronicles. It was also called a

frakki

. It was used from

the 5th to the 7th century, but then lost popularity. Examples have been found in graves.

It was single bladed with a heavy metal head, commonly slim becoming wider at the

b

lade. The Franks hurled their axes together at a signal. The Goths also used this weapon,

borrowed from the Franks.

GLAIVE

A weapon with a blade or a head. It meant, at different times, a sword, spear, lance or

b

laded weapon on a handle. Glaive later meant a lance that was the winning mark in a

race, the winner taking it as his prize. Glaive comes from Old French for lance or sword,

probably from Latin

gladius

(sword). The term is commonly used now for the later

medieval staff weapon with a long, curved single-edged blade attached to a long wooden

staff. Its blade was broader than that of a bill, with the edge on the inner curve. The blade

sometimes had additional hooks and projections,

GOEDENDAG (GODENDAC)

Arms of the warrior 251

One of the names for a later medieval staff weapon; others include bill, halberd, pole-

axe, gaesa, croc, faus, fauchard, faussal, pikte, guisarme and vouge. Some of the names

may be variants for the same thing. Goedendag means ‘good-day’ or ‘good morning’—

the poet of the Battle of Courtrai

zv244

says it meant ‘bon jour’. It was the main weapon of the

Flemish at Courtrai in their victory over the French in 1302 when it was used two-

handed. Because of the illustrations on the Courtrai Chest it is probably correctly

b

elieved that the weapon was a club or mace with an attached metal spike. It may be

significant that the similarly named morning star was a type of mace. One chronicle says

it could be used for cutting, so some historians believe it is a type of halberd. Luckily my

friends do not greet me with it each day.

GUISARME (GISARME)

Staff weapon with a long blade, sharpened on both sides and ending in a long point, up

to eight feet in length. It derived from the scythe and the prong. There is a Catalan

reference to it in 977 and it may have originated in Andalusia. The name guisarme is Old

French. The length of the blade allowed the addition of hooks and projections. With these

additions it became a

fauchard

—

p

robably its most common medieval form. It could be

used for cutting or thrusting. It was similar to the glaive, but with a shorter blade. It was

popular in Scotland. Sometimes bells were attached to frighten approaching horses.

HALBERD

A long-handled staff weapon with a blade that was both pointed as for a pike and

edged as an axe, probably the most common staff weapon. Often a curved spike projected

at the rear of the axe head. The name first appeared in a Swiss poem of the 14th century.

The halberd was probably first used by the Swiss, as at Morgarten in 1315. At Sempach

the halberd crushed the knights of Duke Leopold, and at Nancy a halberd slashed Charles

of Burgundy across the face, causing him to be unhorsed and killed. It was replaced in

p

opularity by the longer pike, more effective against cavalry. The Swiss are said to have

lost faith in the halberd after their failure at Bellinzona in 1422.

HAMMER

Often referred to as the war-hammer. Like the axe it could be a tool or a weapon. It had

a metal head with a flattened surface for striking. It reappeared in the 13th century and

was much used during the Hundred Years’ War. A hammer is represented on a 13th-

century tomb effigy in Malvern Abbey Church, Worcestershire. This has a short handle

and a spike at the back of the head. Several are depicted in later Spanish paintings, some

with long handles. A 15th-century hammer head with a spike at the rear is in the Wallace

Collection.

HILT

The handle or grip of a sword or dagger. Petersen detected no less than 26 types of hilt

for swords of the Viking period. The hilt was formed over a tang from the blade, slotting

over the guard, covering the grip, with a pommel to stop the end. The hilt was often

decorated in patterns, for example with inlaid copper and brass. Thin sheets of tin, brass,

gold, silver or copper might be used. Some were marked with a maker’s or firm’s name.

On one lower guard is lettering

‘Leofric me fec[it]’

(Leofric made me), possibly meaning

the hilt rather than the whole sword. The transverse piece of metal forming part of a

sword hilt is the crossguard, separating it from the blade.

The routledge companion to medieval warfare 252

LANCE

A cavalry weapon with a long wooden shaft and metal head. The name is from Old

French via Latin

(lancea),

but possibly of Celtic origin. Initially it was a spear. By the

end of the 11 th century lances were used couched (i.e. held underarm) for concerted

cavalry charges. This type of attack was known in the Middle East as the Syrian attack,

though a Mamluke cavalry tactic was known as ‘playing the Frank’. On the

Bayeux

Tapestry

some lances are couched but others are used overarm, perhaps because the lance

was not especially useful against infantry. In the later Middle Ages the lance became

more specialised, thicker and heavier than a spear and with a shaped

zv245

grip, balanced for

holding at the centre. The forward part thickened before the grip, thus providing

p

rotection for the hand. A wing attachment to the head prevented the lance burying itsel

f

too deeply in its target. A lance rest was sometimes fixed to a knight’s breastplate, to

make carrying easier. The rest could be attached to a spring so that it clipped shut when

not in use. It became common practice to place the lance across the horse with the lance

head on the left of the horse. The 1277 brass of Sir John d’Abernoun shows a lance with

a straight shaft, a spear-like head and an attached pennon. Lighter lances were still used

in the later Middle Ages, for example by the fast moving

stradiots

of Byzantium. Plate

armour lessened the killing power of the lance. Tournament lances were normally

b

lunted, commonly with a head called a coronal, orreplaced by relatively harmless

substitutes such as canes. The lance was the chief weapon in jousting.

LONGBOW

The longbow is associated with English archers in the Hundred Years’ War. Longbows

were not then a new invention. Bows with long wooden staves, often of yew, had been

p

roduced for centuries and have been found, for example, in excavations in Scandinavia

and Ireland from the Roman and the Viking periods. The Vikings were great exponents

of the bow. Norman bows on the

Bayeux Tapestry

should probably be described as

longbows though perhaps not as long as was later common. The crossbow became the

most popular bow in the 12th and 13th centuries but the longbow reached its golden age

during the Hundred Years’ War. The Welsh used longbows but it is unlikely that the

English learned of it from them. The longbow had a wooden stave and a string. The stave

was commonly of yew, rounded with a D-shaped central section. The sapwood of the

stave was on the outside, the heartwood towards the archer—giving the stave a natural

spring. Longbow length needed to be in proportion to the archer’s height. Its typical

length was about six feet. There was a thickened grip in the centre of the stave for the left

hand, allowing the arrow to rest on the top of the grip. The right hand drew the string,

normally of gut, sometimes hemp. The string was looped over each end of the stave. The

centre of the string was usually strengthened at the nocking point. Pieces of horn or nocks

were added at the ends of the stave to help hold the string in place. The best draw was to

the chest and required considerable strength. A good longbowman needed strength and

the knack of drawing and releasing at the correct moment. Woodland and forest areas

p

roduced the most experienced longbowmen. Whether or not Robin Hood actually lived,

the tales link a forest area with the weapon. What made the longbow so effective was its

tactical use by large groups of trained archers in selected forward positions, shooting in

unison. The English used longbows both in sea warfare, as at Sluys, and on land as at

Arms of the warrior 253

Crécy, Poitiers and Agincourt. Longbowmen were used as mercenaries; Scots for

example were hired by the French. The English were reluctant to abandon their famous

weapon and continued its use into the Tudor period. Longbows were discovered aboard

the

Mary Rose

. Elizabethan writers romantically sought to encourage its continued use,

but in the real world gunpowder had taken over.

MACE

A heavy club with an added head, probably initially an infantry weapon, its prime use

in the Middle Ages was by cavalry. It needed to be light and was often of bronze. The

head sometimes had an added spike or projection. The mace was known in 10th-century

Moorish Andalusia. It appears on the

Bayeux Tapestry,

as a clubbing weapon. Later the

heads looked like dart flights, with wings projecting from a central spoke. One such is in

the Museum of London. Often the head had a projecting spike like a spear. Maces are

depicted on the

Maciejowski Bible

and on 13th-century

zv246

sculptures at Lincoln and

Constance. It was often used in ceremonies, for example by lawyers, clerics and royalty,

and was a common weapon in tournaments. The later medieval Gothic Mace was metal,

its shaft thickened at the grip, sometimes with a guard and pommel like a sword hilt.

Animal-headed maces were used by steppe nomads and the Turks. Maces could be o

f

b

ronze, iron or steel and for ceremonial use of silver or gold. The morning star was a type

of mace.

MISERICORDE (MISERICORD)

A small dagger, a knight’s reserve weapon, said to be named from its use for the death

stroke, when the victim could ask for mercy or be killed. Alternatively it is suggested the

name meant that the dagger was ‘merciful’,

p

utting the injured victim out of his misery.

The term appeared first in the Treaty of Arras of 1221, named alongside the knife. The

misericorde often had a straight blade of triangular section with a sharp point. It is

sometimes shown carried on the right side, fixed by chain to the belt.

MORNING STAR

A later medieval staff weapon, generally combining a mace with a spear point, named

from the German

morgenstern

(possibly ironic—from seeing stars after being struck), but

p

robably from its appearance, the head looking like a spiky pineapple, or with

imagination a star. Hewitt suggests the morning star was a type of flail attached to the

staff by a chain, the head being globular and spiked and looking like a star, but this is not

generally accepted.

PIKE

A long wooden staff with a spear-like head, up to 18 feet long with a ten-inch steel

head. Pike is the common English term for such weapons though variations include the

goedendag and partisan. It was seen as the weapon of inferior ranks. Wace wrote o

f

‘villeins with pikes’. It was originally an infantry weapon for defensive use. It was held

with the butt on the ground, steadied by the foot, with the head towards the enemy. It

p

roved useful against cavalry. Unlike archers, whose weapons were only useful when the

cavalry was at a distance, pikemen could hold a charge. Special formations were

developed, such as the hollow square or circle with men facing outwards all round. The

p

ike was a standard defensive weapon in the 14th century. Its effectiveness was

demonstrated by the Flemings at Courtrai in 1302. The Scots used pikes at Stirling in

The routledge companion to medieval warfare 254

1297 and Bannockburn in 1314, forming schiltroms, outward-facing groups. The English

used this formation under Harclay at Boroughbridge in 1322. The Swiss won victories

with pikes and became the favoured late medieval mercenaries. They developed offensive

tactics of advancing phalanges. Charles the Bold of Burgundy’s ordinance of 1473

detailed infantry tactics with pikemen kneeling while archers shot over their heads.

POLE-AXE

The pole-axe began life as an axe on a long pole, an infantry weapon. In its more

familiar form it was a late medieval staff weapon, similar to a bill,

guisarme

or halberd.

Its head was an axe blade with a spear point and hammer at the rear. The hammer

distinguished it from similar weapons and it was used to stun or to poleaxe. It was also

used by knights when fighting on foot.

POMMEL

The pommel was the extreme end of the sword hilt or dagger. Swords were constructed

so that the blade had a projecting tang over which the parts of the hilt were threaded. The

p

ommel completed the hilt and held it in place, the tang being hammered over the end o

f

the pommel. The term came from Latin for a little fruit, in French a little apple. Pommel

shapes help to distinguish types of sword—Oakeshott has identified 35. Modern attempts

to

zv247

describe these shapes include cocked hat, tea cosy, scent-stopper and brazil nut.

Pommels were often decorative; one from Sutton Hoo was decorated with gold and red

garnets. A dagger from Paris was marked with arms on the pommel. The most common

Viking pommel had three lobes. A disc-shaped pommel was popular in the later Middle

Ages. After the medieval period old detached pommels proved useful for shopkeepers’

weights. (Note: the word pommel was also used for the upward projecting front of a

saddle.)

QUARREL (SEE BOLT)

SCABBARD

Container for a sword or dagger. The term is from Old French, the English equivalent

b

eing sheath. It protected the blade when not in use. Wood and leather were common

materials, as in the Sutton Hoo example. The inside was sometimes lined with wool so

that lanolin would prevent rust. The scabbard could have a locket at the top to grip the

blade just below the hilt. The scabbard could be made of

cuir bouilli

(leather soaked and

dried). The scabbard might be attached to a baldric, worn over the shoulder, or on a belt.

Several scabbards survive, A 13th-century one from Toledo is made of two thin pieces o

f

wood covered with pinkish leather. It ends in a chape of silver, a projecting piece o

f

metal. Oakeshott believes the chape was meant to catch behind the left leg for ease in

drawing the sword. It also protected the vulnerable end of the scabbard.

SEAX (SAX)

A short sword or knife with a heavy, single-edged blade wielded one-handed,

associated with the Franks and Alemans. It was used by the Anglo-Saxons and Vikings.

Seax

was its Old English name, possibly from the Saxon folk as the

franciska

from the

Franks though it may derive from the Latin

sica,

a Thracian weapon. Blade types

included the angle-

b

acked shape from the 7th century. The seax varied in length from 6

to 18 inches, with 12 inches the most common. The blade usually had a tang with a hilt,

like a sword. The shorter seax is sometimes called a scramasax.

Arms of the warrior 255

SHORTBOW

The composite bow favoured by mounted steppe nomads. The stave was of three

pieces—a centre and two wings. The shape was formed over pieces of wood. Horn was

glued to the inside of the wood, sinew to the outside, giving flexibility and power. The

stave was bent backwards and secured with the string. Its smallness and power made it

ideal for horsemen. The Saracens and Turks used shortbows. Shooting backwards over

the shoulder was a skilled but common practice.

SLING

Used by David against Goliath and by medieval armies, made from a strap fixed to two

strings, or to a staff. Whirling it built up speed before one end of the sling was released,

p

rojecting the stone. The sling of a trebuchet worked on the same principle. In ancient

warfare slingers opposed cavalry. The sling appears in several manuscripts e.g. the

P

salter of Boulogne,

the 13th-century

Harleian MS 4751

and the

Bayeux Tapestry

(for

hunting). It was used through the early and central Middle Ages. Geoffrey of Anjou used

slings at Le Sap in Normandy, when ‘many slingers directed showers of stones against

the garrison’. Imperial forces used slings against Tortona in 1155 and Crema in 1159,

when slingers operated from a belfry platform. Jaime I of Aragón used slingers like this

in Mallorca. A cause of confusion is that a ‘slinger’ in Latin

(fundator, fundibalarius,

f

undbalista)

could be using a hand sling or a throwing engine. The ‘Balearic slingers’

p

robably worked engines. Richard the Lionheart was said to move on the march more

swiftly than a Balearic sling. Slingers of uncertain type were used by Fulk le Réchin o

f

Anjou at Le Mans. A 14th-century sling with a leather cup for the stone was found at

Winchester.

zv248

SPEAR

A stave with a pointed end for thrusting or throwing. An ancient wooden weapon that

could have just a sharpened and hardened end. Stone and bronze were used in prehistoric

times for the head. By the Middle Ages the head was normally iron, with a sharp pointed

b

lade, a tubular shank and a socket riveting it to the stave. Ash was a favoured wood,

anything from 6 to 12 feet long. It was a common Germanic weapon. The word spear is

Old English, though there were other OE words for it. It was the quintessential infantry

weapon. It could be held and used in defence, for example against cavalry, or for

thrusting, the basis for the pike. It could be hurled as a missile like a javelin. The missile

spear would normally be lighter. It could be used from horseback and was the origin o

f

the lance. Spearheads of varied shape, size and design have been found, including leaf-

shaped, angular, triangular, lozenge-shaped, corrugated or barbed. Spearheads for

thrusting often had wings to prevent the spear penetrating too far, so that it could be

retrieved. Medieval armies frequently used spearmen, particularly in the earlier centuries.

Spears figured prominently in warrior burials. The right to carry a spear was the mark o

f

a free man. Throwing a spear against the enemy was a way of declaring hostilities.

SPRING-BOW

The exact nature of this device is unknown but it was probably a kind of crossbow

triggered by the unsuspecting victim. It was a trap rather than a weapon. It was called

li

ars qui ne fault

(the bow that does not fail). The first mention is by Gaimar in

L’Estoire

des Engleis,

where the traitor Eadric devised one to kill Edmund Ironside. The king was

The routledge companion to medieval warfare 256

shown into a privy where there was ‘a drawn bow with the string attached to the seat, so

that when the king sat on it the arrow was released and entered his fundament’. He died.

The device became a figure of speech for any trap that could not fail.

SWORD

The medieval weapon

par excellence

. Iron made a significant difference, producing a

thinner and more flexible weapon. The Roman sword was short and stout, primarily for

thrusting. Its development probably came via the Greeks and Etruscans. Iron swords were

found at La Tène on Lake Neuchatel. Styria was an important centre of manufacture.

Early users were the Celts who developed the pattern-welded blade with strips of iron

twisted together cold and then forged; twisted again and re-forged to the edges. The blade

was then filed and burnished, leaving a pattern from the now smooth surface of twisted

metal. Unlike bronze, iron was worked by forging rather than casting. Iron made possible

a different structure for the sword, with a tang from the blade over which the handle

could be slotted. Iron had advantages but a longer iron sword would bend and buckle i

f

used for thrusting. Early European swords were long with cutting edges. When used by

charioteers they needed length, best used with a cutting action. Much the same is true o

f

cavalry swords. Swords from the first four centuries BC came from bog deposits in

Scandinavia. Those at Nydam had pattern welded blades, about 30 inches long and

mostly sharpened on both edges. A sword at Janusowice from the time of the Battle o

f

Adrianople had a long blade and evidence of a leather scabbard. It had a large bronze,

mushroom-shaped pommel. The sword at Sutton Hoo, old when buried, had a pommel

decorated with gold and red garnets. It had rusted inside its scabbard, but X-rays showed

it was pattern welded. The scabbard was of wood and leather.

Viking swords were outstanding in design and efficiency. What we call ‘Viking’

swords are common to those used over a wider area including Francia. They were o

f

varied styles of blade and hilt. Petersen detected no less than 26 types of hilt. The hilt was

formed over a tang from the blade, slotting over the guard, covering the grip, the end

stopped with a pommel. The most common

zv249

Viking pommel had three lobes but there

were many variations. Most Viking swords were plain but well designed. Some were

decorated with patterns of inlaid copper and brass on the hilt. Thin sheets of tin, brass,

gold, silver and copper might be used. Some had a maker’s name or a firm’s name. On

one lower guard is lettering

Leofric me fec[it]

(Leofric made me). Other names are

Hartolfr, Ulfbehrt, Heltipreht, Hilter and Banto. Ulfbehrt is found quite often, for

example on a sword from the Thames. The name seems a Scandinavian-Frankish hybrid.

Ulfbehrt swords date from the 9th to the 11th centuries. One should probably think o

f

most as made by ‘firms’, no doubt family concerns, rather than by individuals. This

manufacture probably originated in the Rhineland. Another name to appear in the 10th

century, though less frequently, is Ingelrii—about 20 have been identified. A sword from

Sweden reads

Ingelrii me fecit

. One finds other inscriptions and symbols, often

enigmatic, including crosses, lines, Roman numerals and runes. Some names were o

f

owners rather than makers, for example, ‘Thormund possesses me’. Swords were

sometimes named by their owners for example as millstone-biter, leg-

b

iter. Viking

swords became heavier from the 8th century, and in the 10th century there were design

improvements. Later swords were not usually pattern welded and some were of steel,

Arms of the warrior 257

harder and more flexible. They were lighter and tougher with a more tapered blade,

bringing the balance nearer to the wrist, and could be used for thrusting or cutting.

The sword became the weapon

par excellence

of the later medieval knight. The

significance given to swords in literature, to Arthur’s

Excalibur

or Roland’s

Durendal

reflects this regard. It had symbolic value, in oath-making, dubbing, being blessed by the

Church or promised to churches after the knight’s death.

Late medieval swords were shorter and less flexible. Some survive—from burials,

riverbeds and in churches, including ‘Charlemagne’s sword’ which is probably 12th-

century, the sword of Sancho IV of Castile late 13th-century, of Emperor Albert I c.1308

from his tomb, and of Cesare Borgia dated 1493.

zv250

The routledge companion to medieval warfare 258

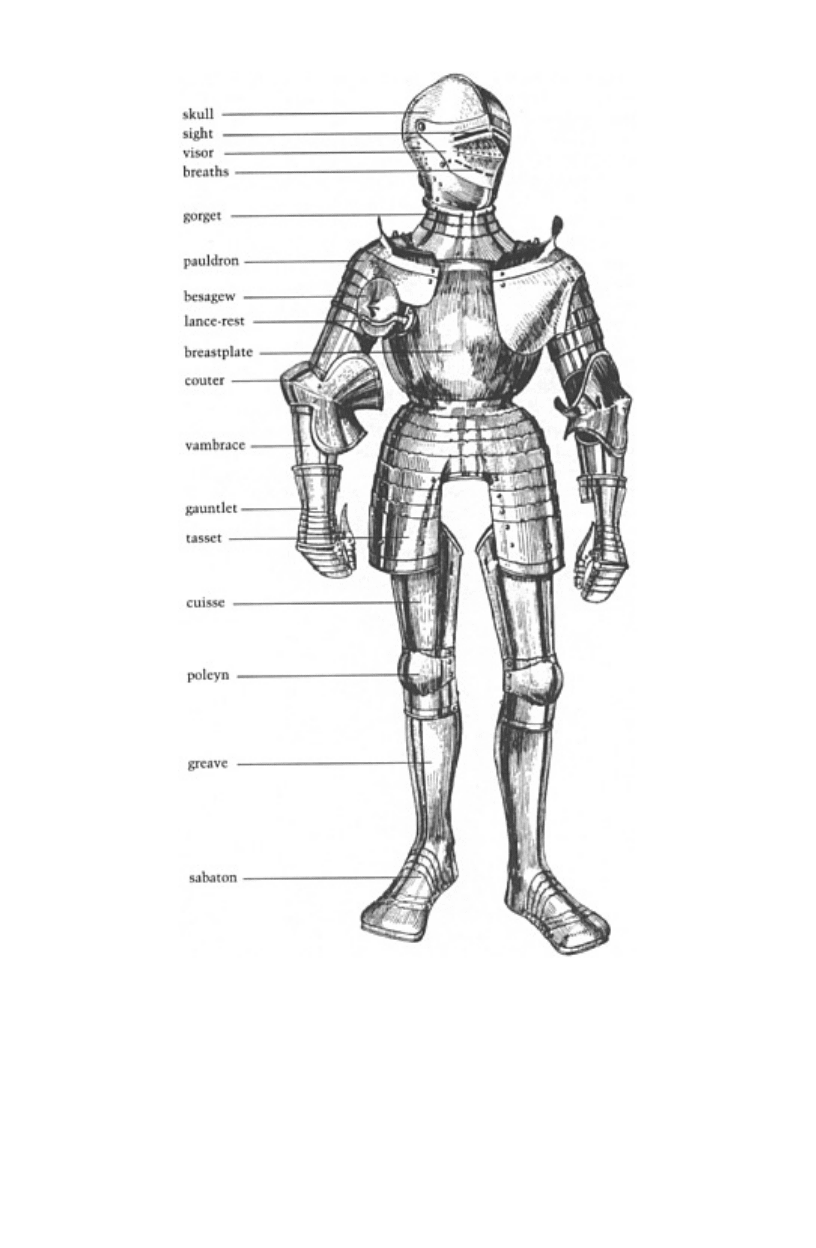

A complete suit of late medieval plate armour

Arms of the warrior 259

14

Medieval armour

A–Z OF TERMS

Ailettes, aketon, armet, aventail, backplate, bard, bascinet, besagew, bevor, breastplate,

brigandine, burgonet, byrnie, chausses, coif, cuirass,

cuir bouilli,

cuisses, espaliers,

gambeson, gauntlets, gorget, greaves, haubergeon, hauberk, helmet, jack, kettle hat,

lance-rest, mail, pauldron, plate, poitrine, poleyns, pourpoint, sabatons, sallet, shield,

spangenhelm, spurs, surcoat, tabard, tassets, vambrace, visor.

OUTLINE HISTORY

There are close links between the development of medieval armour and medieval arms

(see section 13). Again the influence of Roman and barbarian armour is obvious. The

evidence comes from the same kind of sources: survivals, burials, manuscript illustrations

and written accounts. It is equally true that the basic items of armour are of ancient

origin—helmet, body tunic and shield. The Romans had separate items for limb

p

rotection, including greaves. Leather continued in use for certain items; shields were

still commonly of wood and leather. In truth, early medieval armour saw little original

development. Mail was not new and a mail tunic remained the main part of armour.

The major change in medieval armour came with social development, the rise of the

aristocratic mounted knight. The knight used the best armour of his day, which came

gradually to be a complete suit of armour. This occurred in parallel with improvement in

metallurgy and manufacture, with the production of lighter and more flexible steel. Plate

armour began with the introduction of single plates, probably first breastplates. The

helmet came to cover the whole head and neck, with a movable visor for air and vision.

Metal plates were produced for breast, back and limbs. Pieces were introduced to cover

the gaps and protect the more mobile body parts—shoulders,

zv252

elbows and knees.

Laminated armour allowed flexibility to protect vulnerable parts. It consisted of separate

strips or lames of metal, riveted together and overlapping, moving like a lobster shell.

There was also constant change in style and fashion.

A–Z OF TERMS

AILETTES

Protection for the shoulders or neck, like epaulettes. The word is a diminutive from

Latin

ala

via French

aile

for wing, describing their appearance. They were usually made

of buckram or leather and sometimes carried metal plates. Ailettes became popular from

the 13th century. They are generally depicted standing upright on the shoulder, so their

p

urpose may have been to protect the neck rather than the shoulder itself. The German

equivalents were

Tartschen,

meaning shields—suggestive of their purpose. They were

generally rectangular but some were in lozenge form and others circular. Oakeshott