Bourke Ulick J. Aryan Origin of the Gaelic Race and Language

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

100

MANUSCRIPTS.

and of

placing

it in

its

objective

fulness before the

eye.

The

fowl

in

the

fable

did

not

see

the

value of a

gem.

He

declared he

would

rather have

one

grain

of

barley

than

the most

precious

and

valuable of

gems.

Gems

to him

were

things

he

could not

eat.

He

had no

power

of head

to

soar

higher

than the

notion of

eating

and

drinking.

A

gem

to a

bird

was

certainly

useless. There are men

who

prefer

the

possession

of material

value,

which

contributes

to their

gross

animal

life,

to

all the

precious

paintings

ever

pencilled

in ancient or

modern

times

by

Grecian,

Dutch,

Italian,

or

Spanish

artists. A

man

who

values

money

and material

riches

for

what

they

bring

of

earthly

enjoyment,

of

civic

honor,

social

state,

or

sensual

living,

cannot

appreciate

the

possession

of

precious

pictures

as

creations of intellect and works of

genius.

Of course he

may

value them as he

values bank

notes

;

but

that

is

not

intellectual

appreciation.

Painting

as well

as

music,

does

not satiate

animal

cravings,

or

satisfy

mere

earthly

tastes.

Persons

of

mind,

of

thought,

of

intelligence,

alone can

understand those works of intellectual

creation.

And how

very highly they

are valued is

plain

from the

fact that

kings

and

emperors

and

governments,

in

modern

and ancient

times,

prefer

to

have them

to

the

possession

of

hundreds of thousands

of

pounds.

The

value

of

a

language,

too,

must not

be estimated

by

its

commercial

worth. Men of mind

and of

linguistic

knowledge

alone

are

capable

of

estimating

it

at its real

value.

3.

Every

one

knows

how

highly

rare

books

are

prized

by

the

learned.

Above

all the

manuscript

works

of renowned

writers,

such

as

the Bard

of

Stratford-upon-Avon,

whose

house,

even

as

a

natural

heirloom,

has

been

purchased

(in

1847)

by

the

British Government.

Thj

manuscript

by

Dante

of the

Divina

Co:nmcdia

would

PLATO. 101

be

purchased,

not

alone

by

the

Florentines,

but

by every

nation

in

Europe,

at a

great price.

The

manuscript

of

the

Canterbury

Tales would make a

fortune for their

pos-

sessor.

Every

people

of civilization

and

intelligence

throughout

the

world

appreciate,

in

the

highest

degreo,

the

creations

of

gifted

genius,

far

above all

the

material

splendour

of Eastern

monarchs.

It

is

in this

way,

too,

that

literary

men

value

a

language.

One cannot

argue

or reason with

persons

of

gross

views

regarding

a

subject

which is

intellectual,

which has

nothing

material

about it

the value of which

does

not

present

itself

to

the

view

under

the

appearance

of

bulk,

or

material

profit,

or

social

rank.

On

this

point

the words

of Professor

Blackie are

pertinent:

"People

whose low ambition does

not

soar

above

what is called

1

getting

on

in the

world,'

that

is to

say,

whose

whole

anxiety

is

expended

on

planting laboriously,

one above

another,

a

series

of

steps,

by

which

they may

mount

to

the

highest

possible platform

in the

merely

material

world,

without

the

slightest regard

to

moral or intellectual con-

siderations,

may

well

question

the

utility

of Gaelic

;

for

no

Gael,

I

imagine,

in

these latter

days,

ever

gained

a

penny by

any

remarkable

proficiency

in the

knowledge

of

his

mother

tongue

;

but

those

who

believe with

Plato

and

St.

Paul,

that

money

is

not

the one

thing

needful,

may

bo allowed

to think

otherwise."

If a

manuscript

of

some

great

writer of ihe

past

is

valued

exceedingly;

if

paintings

are

highly prized;

if

an

heirloom,

bequeathed

by

a

dear

friend,

is

carefully

pre-

served

why

not

the

language

of our

fathers

?

The

language

of the Irish

people

is

a

precious

heirloom

trans-

mitted to the

present

generation

of

Irishmen

through

a

period

of

over

two thousand

years.

"

Whose

youthhood

saw the

Tyrian

on

our

Irish coast

a

guest,

102

A

PRECIOUS HEIRLOOM.

Ere

the

Saxon

or

the

Roman,

ere

the

Norman

or the

Dane

Had

first set

foot on

Britain,

or the

Yisigoth

in

Spain

;

Whose

manhood saw the

Druid

rite at

forest,

tree,

and

rock^

The

savage

tribes of Britain round

the shrines

of

Zernebock

;

And

for

generations

witnessed

all

the

glories

of the

Gael,

Since

our Keltic sires

sung

war-songs

round the

warrior

fires

of

Baal !

The

tongues

that saw its

infancy

are ranked

among

the

dead

;

And

from their

graves

have

risen.

those

now

spoken

in

their

stead.

All

the

glories

of old

Erin,

with

her

liberty,

hdve

gone,

Yet,

their

halo

lingered

round her

while

her

olden

Tongue

lived

on

;

For,

'mid

the

desert

of her

woe,

a

monument

more vast

Than all

her

pillar-towers,

it stood

that

old

Tongue

of the

past."

Is

not

an heirloom

so

precious

worth

preserving

?

Surely

yes.

Any

Irishman

who

says

that

his

nation's

language

one

of

such

antiquity,

so rich and

valuable in

the

eyes

of

scholars

is

not

worth

retrieving,

is

sordid,

selfish,

and

at heart

he is

not

divested

of

those

traits of

character

which

belong

to the

uncivilized and the

barbarian a

lack

of

that

faculty

which

appreciates

learning,

knowledge,

intelligence.

The writer has

heard

several Irishmen

educated

men

repeat

that the

Irish

language

is not

worth

preserving.

These

men

regarded

the

language

from

a

material

point

of

view,

from

its

productive

value

in

the

money

market,

or

in

society

. He

could

understand

how

one

could

be so

blinded

by

the

love of

England

that

he

would,

following

the

fashion of

people

in

position,

see

nothing good

in the Nazareth

of

mother-land

;

bat for

an

Irishman

and

a

Catholic

priest

to

say

that

the

national

heirloom,

bequeathed

him

by

his

Irish

Catholic

forefathers

not

worth

keeping,

is

expressing

a

proposition

which

is

simply

revolting

to

every

sense

of

our

intelligent

nature,

AN

AMERICAN BISHOP.

103

as

a civilized

and

enlightened people,

which

is

subversive

of the

national

character of

the Keltic

race,

that for

thousands

of

years

have

been,

with a

force

strong

and

enduring

as if

it

sprung

from

nature,

devoted to

the

tra-

ditions

and the historic

glories

of

the

past.

4.

In

the

opinion

of men of

thought,

the

acquisition

of

knowledge

is

better

than the

possession

of

money, parti-

cularly

the

knowledge

of a

language,

ignorance

of

which

is

deemed

a

shame

ignorance

of

one's

mother

tongue.

The writer

has before

him a

letter

received

while this

page

is

passing

through press,

from an

Irish

gentleman

at

present dwelling

in

Sumter,

South

Carolina

a

Mr.

Barrett.

He

states

that

the

Most Rev.

Bishop Lynch

declare!

to

him

:

"

I

would

give

a thousand

dollars

to

be

able

to hear

confessions

in

the

language

of

my

fathers."

A similar statement

has been sent

by

the Rev. John

MacNulty,

Pastor,

Caledonia,

Dominion

of

Canada,

that

the

Bishop

of the

diocese declared

he

would

rather

than

the

possession

of

thousands

of

pounds,

have

a

knowledge

of even a

little

of the

speech

of the

sages

and saints

of

his

own mother

Eire."

The

writer has met

over

a

score

of

Irishmen who

have,

since

they

emigrated

to

America,

learned to

speak,

in

a

foreign

land,

the

language

which

it

was their misfortune

not to

have

learned at

home.

This fact

shows with

what

ardour

Irish

-Americans love

the

language

of their

fore-

fathers.

There

are,

thank

God,

at

home in

Ireland

and

abroad

in

America

and

Australia,

many

men of

mind

and

of

scholarly

attainments, who,

like those most rev.

digni-

taries,

prefer

the

acquisition

of

knowledge

to the

posses-

sion

of the

mighty

dollar. Men of

this class will

ever

value

learning

and

scholarship

above

silver

and

gold.

*

"

Morum

priscovum

semper

tenacissimi

fuerunt

Celtic

populi."

Zeuss

Gram.

Celt-ca,

p.

916.

104 OUT BEGONE !

5. It

is not

by

bread

alone

that

man doth

live. And men

of

intelligence

in

every

clime

will

always appreciate

that

which is

stamped

with

the

image

of

genius,

nobility,

and

historic worth.

If

those Irish

gentlemen

and

ladies, too,

who do not

hold

in

esteem the

language

of their

fathers,

care not for

its

preservation,

the

fault

cannot at

present

be

helped.

Let the

language

fade

away

and

die

in

peace,

but

do not

scoff at

it,

scorn

it,

treat it as even its worst

persecutors

in

days

past,

did not

treat

it

with

contumely

and dis-

dain. It

is

not a

sign

of filial

devotedness to

beat

one's

grandmother,

and to turn her

out

of the

house before

the

term

which

nature has fixed for

the

close of her

life

has

arrived. Our mother

tongue

is

still alive. It

has

a

resi-

dence

in

Connacht.

It

is

fading

;

to

be

plain,

it

is

dying.

Is it

a

sign

of

filial

devotion

to

say,

"

Out

begone

!" A

sad

retribution is

threatened

against

children that

act

undutifully

towards

parents.

Let

us

take care

that

no

social retribution

is in store

for

un-Irish

Irishmen

who

despise

and hunt to

death their mother

tongue.

In an

appeal,

addressed

by

Professor

Blackie,

on

the

12th

September,

1874,

to the

members

of

the

Argyle-

shire

gathering,

requesting

Highlanders

to

contribute

the

sum

of ten

thousand

pounds

to

enable him to

estab-

lish

in

the

University

of

Edinburgh

a Keltic

chair,

he

writes :

"

Yet,

somehow

or

other,

by

sad

neglect

and

a con-

currence

of

untoward

circumstances,

the venerable

lan-

guage

of

the

Gael,

in whose

picturesque

phrase

the

sub-

lime

scenery

of our

country

has been so

admirably

photographed,

is

systematically

neglected by

those who

should

naturally

cherish

it.

This most

unreasonable

and

unnatural

neglect

is the cause

of

the sad blank

in

the

department

of

the

Keltic

language

and literature.

There

A KIND WORD.

105

are Professors

eminent for

their

knowledge

of

Keltic

philology

in

German

Universities,

but none

in

Scotland.

The

existence

of this blank

is a blot on

the fair

scutcheon

of

our

national

intelligence,

which

ought

to be

removed

;

and I

appeal

to

you,

as

intelligent

Keltic

gentlemen,

to

give

me a

helping

hand in

its

immediate

removal.

If

you

do

so,

you

will at

very

little

expense

achieve

a

five-

fold

good

you

will

(1)

co-operate

with

the

founder of

the

Sanscrit

Chair,

Edinburgh,

in the

creation of a

great

school

of

comparative

philology

in

the

metropolis

of

Scotland

;

you

will

(2)

elevate the tone of

the

Highland

pulpit,

by giving

to

the native

preachers

a

more

mascu-

line

hold of the venerable

language

which

they

wield

;

you

will

(3)

advance

the

teaching

of

English

in

the

schools

of Scotland

by

that

aid

which

every practical

teacher

knows can

be

given

only

by

the

apt

comparison

of

the mother

tongue

;

(4) you

will

enrich the

intellect

and warm

the

fancy

of the

people

in

the

North

by

cher-

ishing

those

gallant

memories,

and

fanning

those

gene-

rous

sentiments

which

it

is

the

mistaken

policy

of

some

to obliterate

and to

extinguish

;

and

finally

you

will

(5)

gain

for

yourselves

by

one

stroke

the

love

of

the

High-

land

people,

and

the

respect

of

all

the

great

scholars

and

the

large

thinkers of

Europe."

(106)

CHAPTER VI.

JTo

those

not of

Irish

origin

of what

use

is a

knowledge

of

Irish

?

Much in

every

way.

The

primaeval

Aryan

race.

How the

science

of

philology points

them

out,

and shows

where

they

dwelt.

Emigration

westward :

Greek,

Latin,

Keltic.

The

Gaelic

family

of

the

Aryan

race

the earliest

in

their

migration

to

the

west of

Eu-

rope

;

to

Iberia

;

some

to

Northern

Italy,

Helvetia,

Gaul, Britain,

and lerncj or

Eire.

Authorities for

these

statements

Newman,

Pictet,

Sullivan,

Geddes,

Pritchard,

Bopp,

Blackie,

Schleicher.

Keltic

installed

in the

hierarcy

of the

Aryan

tongues.

Though

the

last

installed,

the Irish

Gaelic branch

is the

purest,

the

fullest,

the best

preserved,

the least

affected

by

change

of

all

on account of

the

insular situation

of the Irish

Keltic race.

(1)

Therefore,

for

all lovers of

philolo-

gical

research a

knowledge

of Irish

is as

necessary

as

a

knowledge

of

Sanskrit

;

nay,

more so.

(2)

It

is

at

the door for

European

scholars,

an

El-Dorado

which

they

neglect,

while

they

weary

themselves

by

needless

journeying

to the

East.

(3)

The

lips

of a

living

Gaelic

speaker

a

nobler and a surer

source

of

philolo-

gical

science than the

graves

of dead

Rabbis

and

mummied

Bramins.

(4)

Philology

a

sister

science

to

Ethnology

:

both are

in accord

with the

inspired

writ-

ings

of

the

author of

the

Pentateuch.

(5)

Irish Gaelic

being

free

from

phonetic

decay

in the

past,

and affected

least of all

by foreign

influence,

is of

great

use

in

set-

ling

the vexed

question

of

classic

pronunciation

re-

garding

the natural

sounds

of

the

consonants

g,

c

}

and

the

vowels

a, e, i,

u.

The reader now

sees

the

value

and

interest which natives

of

Ireland

should attach

to

the

vernacular

speech

of

their

country.

A PRIMAEVAL TONGUE.

107

Regarding

tliose, however,

who

are

not

of

Irish

origin,

it

will be

asked,

"

Of

what

use is

a

knowledge

of

the

Irish

tongue

to

them,

for

they

are not natives of

Ireland.

Why,

then,

should

they

be

expected

to

unite

in

preserv-

ing

all

that remains

of Ireland's

language

?

To

answer

this

question

fully

one must ascend

the

heights

of

the

history

of human

speech.

The

primaeval

language

of

man,

called

amongst

the

learned

of the

present

day

-the

Aryan,

of

which

Keltic

is

a

dialect,

brings

us back to the

period

before

the human

family

had

emigrated

from the first

home wherein

they

had

settled.

For the

sake

of

those who

are not

acquainted

with the

science

of

comparative

philology, by

the aid of which

scholars can

point

out

clearly

and

distinctly

the

connexion

as well as the

difference between

living languages,

and,

at

the same

time,

trace

all

to

one common

origin,

it

is

ne-

cessary

to

state,

that

by

aid of this

science and

by

kindred

aids,

without

direct reference

to

revelation,

men of lite-

rary

research

have

found

proofs

the

most

convincing,

to

shew

that before

the

dispersion

of the human

family,

there existed

a

common

language,

"

admirable

in

its

raciness,

in

its

vigour,

its

harmony,

and

the

perfection

of

its

forms."

The sciences

in

connexion with

languages

are,

in

this

respect,

quite

in

accord

with the

tradition

of

every

nation

on the

globe,

and

with

the

teaching

of

history

and the

inspired writings

of Moses and the

Prophets.

These

linguistic

sciences

do

not

deal

with

any parti-

cular

language

;

they

take in all

modern

radical

tongues,

and

like

those

who sail

up

separate

small

rivers,

till

they

reach

a

common

source,

they

trace the

different

streams

of

language up

to

a

primaeval

fountain-head,

from

which

all

the

European

dialects

have

taken their rise.

108

ARYAN.

Tims,

it

has been discovered

that

there

had

been,

ante-

rior

to

the

dispersion,

one common

primaeval speech.

Learned

men

in

England,

France, Switzerland,

Ger-

many,

have,

by

their

labors,

within the

past

half

century,

contributed

to

this

important

result.

It

is

the same class

of

scholars

in

Germany

and

Swit-

zerland,

and

not

Irishmen,

who have shewn

that

Irish

Gaelic

is,

in

origin,

one with

Sanscrit, Greek,

and

Latin

;

and that

it is

amongst

the oldest

branches of

the one

primaeval Aryan tongue.

First

The Irish

speech

is, therefore,

for

all

lovers of

languages,

and

for all who

wish

to

become,

like German

scholars,

acquainted

with the first

tongue spoken by

the

human

family,

equal

in

value

to

Sanscrit, Latin,

and

Greek.

This

is not

merely

the

opinion

of the writer

it

is

held

by

Professor

Blackie of

Edinburgh,

by

Monsieur Pictet

of

Geneva,

by

Bopp,

by

Geddes,

Professor of Greek in

the

University

of Aberdeen. Geddes

says

(Lecture

the

Philologic

uses

of

the Keltic

tongue published

by

A

Browne

&

Co., Aberdeen,

1872)

:

"

A

great

field of

in-

vestigation,

as

yet

comparatively

unexplored,

lies before

you

in

your (the

Gaels

of the

Highlands)

own

tongue

it

is

an El-Dorado for the

winning."

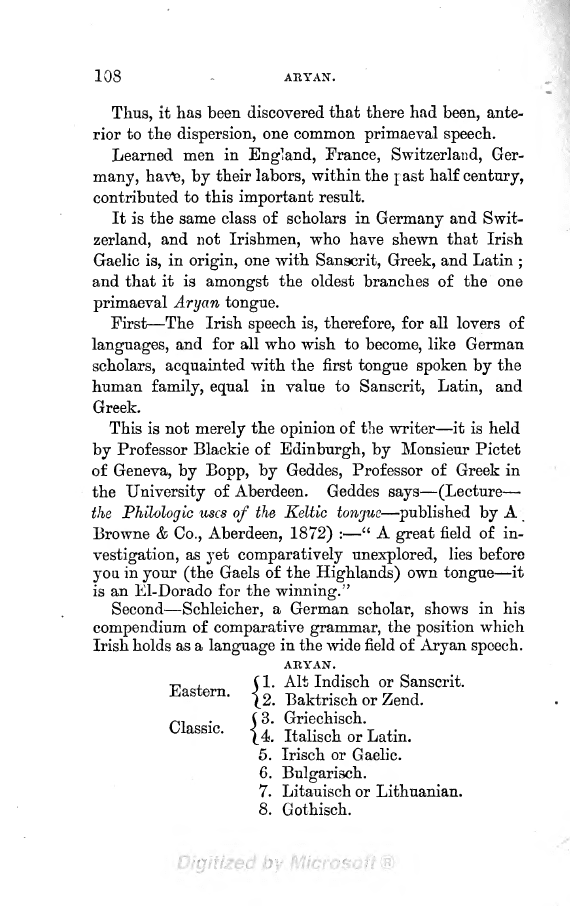

Second

Schleicher,

a

German

scholar,

shows

in

his

compendium

of

comparative

grammar,

the

position

which

Irish

holds

as

a

language

in

the wide field of

Aryan speech.

ARYAN.

(1.

Alt

Indisch

or

Sanscrit.

Eastern.

{

2. Baktrisch

or

Zend.

^T

(3. Griechisch.

Classic.

|

4 Italisch

or

Latin.

5. Irisch

or

Gaelic.

6.

Bulgarisch.

7.

Litauisch or Lithuanian.

8.

Gothisch.

THE GARDEN

OF

EDEX.

.

109

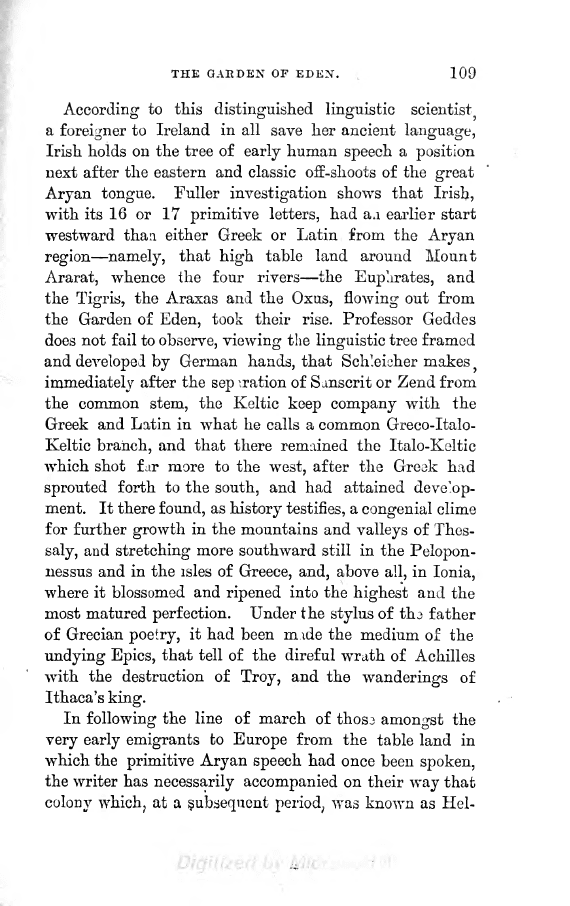

According

to this

distinguished linguistic

scientist^

a

foreigner

to Ireland

in all

save

her ancient

language,

Irish holds

on the

tree o

early

human

speech

a

position

next after

the

eastern

and classic

off-shoots of

the

great

Aryan

tongue.

Fuller

investigation

shows

that

Irish,

with its

16 or

17

primitive

letters,

had

aa earlier

start

westward

than either

Greek

or Latin from

the

Aryan

region

namely,

that

high

table

land

around Mount

Ararat,

whence

the four

rivers

the

Euphrates,

and

the

Tigris,

the Araxas and the

Oxus,

flowing

out from

the

Garden

of

Eden,

took

their

rise. Professor

Geddes

does

not fail

to

observe,

viewing

the

linguistic

tree framed

and

developed by

German

hands,

that Schleicher makes

?

immediately

after

the

sep

iration of Sanscrit or

Zend from

the common

stem,

the

Keltic

keep

company

with

the

Greek

and Latin in

what he calls a common

Greco-Italo-

Keltic

branch,

and that

there remained the

Italo-Keltic

which shot fur

more to

the

west,

after the Greek

had

sprouted

forth to the

south,

and had attained

develop-

ment. It

there

found,

as

history

testifies,

a

congenial

clime

for

further

growth

in

the

mountains and

valleys

of

Thes-

saly,

and

stretching

more

southward still in the

Pelopon-

nessus and

in the isles of

Greece,

and,

above

all,

in

Ionia,

where

it

blossomed

and

ripened

into

the

highest

and

the

most

matured

perfection.

Under

the

stylus

of

tha

father

of Grecian

poetry,

it had

been

m

ide the

medium

of

the

undying

Epics,

that

tell of

the direful

wrath of

Achilles

with

the destruction of

Troy,

and the

wanderings

of

Ithaca's

king.

In

following

the

line

of march

of

thosa

amongst

the

very

early emigrants

to

Europe

from the

table land

in

which the

primitive Aryan speech

had

once

been

spoken,

the writer has

necessarily accompanied

on

their

way

that

colony

which,

at a

subsequent

period,

was

known as Hel-