Borovik A. Shadows of the Truth: Metamathematics of Elementary Mathematics

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

11 Pedagogical Intermission:Nomination and Definition 125

The supply of names is all-important, but also important is a

structural framework for their use, as it can be seen seen from an-

other story, from Sw iatoslaw G.

4

ixG., Swiatoslaw

About the age of eight I was told about the numbers like trillions,

quadrillions etc. I was a pu p il in a musical school so I was able

to count to octillions, nonill i ons, duodecilions maybe. . . Then I

started to wonder what are the limits. I.e. how many numbers can

one name in La tin to give names to powers of 1.000.000.

I knew the names of the intervals: tercja, kwarta, kwinta, sek-

sta etc. (this was in Polish: third, forth, . . . it would not work in

English). And I knew that they come form Latin, so when I heard

quadrillion, quintillion I was able to figure out sextillion by myself.

Until novendecillion. I did not know how to say twenty in Latin

then, this made me puzzled how long would tha t go.

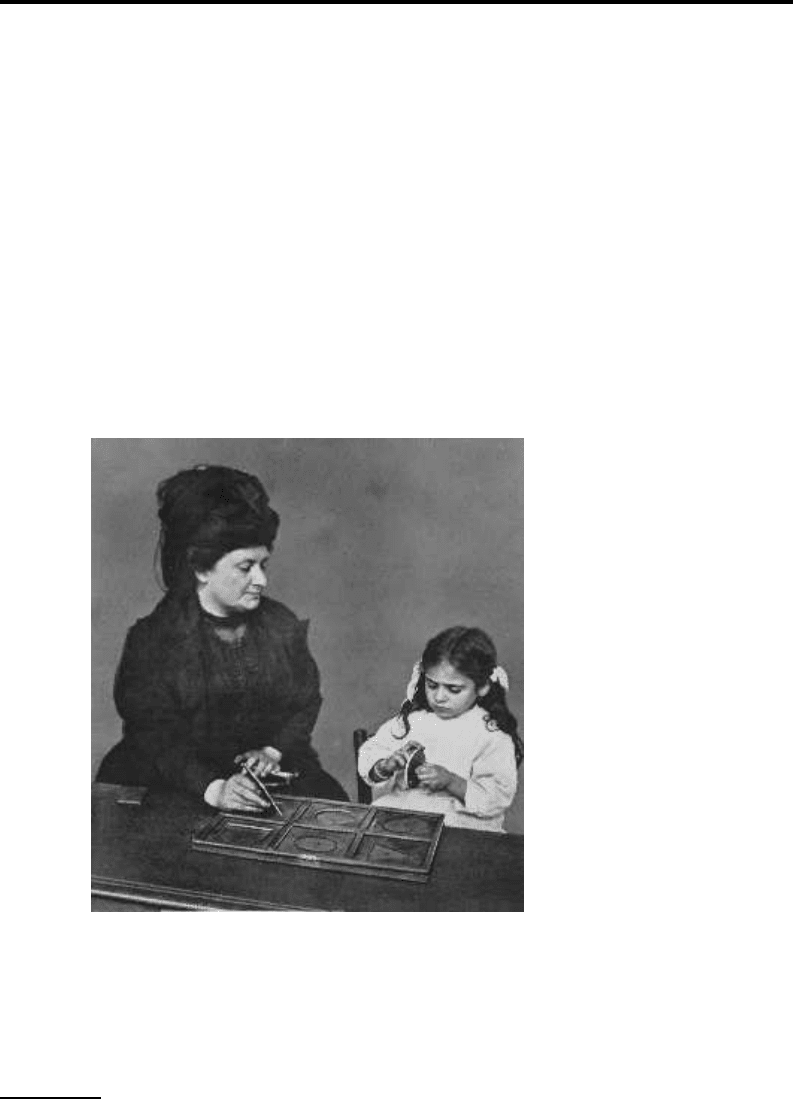

Fig. 11.1. Ma ria Montessori (1870 – 1952) giving a lesson in touching geo-

metrical insets [696].

Nominati on (that is, naming, giving a name to a thing) is an

important but und erestimated stage in development of a mathe-

4

SG is Polish, professor of mathematics. His mathematics instruction at

the time of the episode was perhaps in both Polish and U krainian; he

just does not remember.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

126 11 Pedagogical Intermission:Nomination and Definition

matical concept and in learning mathematics. I quote Semen Ku-

tateladze [678]:

Nomination is a principal ingredient of education and transfer of

knowledge. Nomination differs from definition. The latter implies

the description of something new with th e already availa ble no-

tions. Nomination is the calling of something, which is the starting

point of any defini tion. Of course, the frontiers between nomina-

tion and definition are misty and indefinite rather than rigid and

clear-cut.

And here is another mathematician talking about this impor-

tant, but underrated c oncept:

Suppose that you want to teach the ‘cat’ concept to a very young

child. Do you explain that a cat is a relatively small, primarily car-

nivorous mammal with retractible claws, a distinctive sonic out-

put, etc.? I’ll bet not. You probably show the kid a lot of different

cats, saying ‘kitty’ each time, until it gets the idea. [101]

And back to Kutateladze:

We are rarely aware of the fa ct that the secondary school arith-

metic and geometry are the fi nest gems of the intellectual legacy

of our forefathers. There is no literate wh o fails to recognize a tri-

angle. However, just a f ew know an appropriate formal definition.

This is not just an accident: since definitions of many funda-

mental objects of mathematics in the Elements are not d efinitions

in our modern understanding of the word; they are descriptions.

For example, Euclid (or a later editor of Elemen ts) defi nes a

straight line as

a line that lies evenly with its points.

It makes sense to interpret this definition as m eaning that a line

is straight if it c ollapses to a point when we hold o ne end up to our

eye.

5

We have to remember that most basic concepts of elementary

mathematics are the re sult of nomination not supporte d by a for-

mal definition: number, set, cur ve, figure, etc. Basically, mathe-

matics starts with nomination. I have already written [103] about

Vladimir Radzivilovsky and his metho d of teaching mathematics

to ve ry young children. It inv olved a systematic use of an idea—

borrowed from the 19th century Italian educator Maria Montessori—

of teaching children to recognize and name basic geometric shapes:

5

The interpretation of Euclid’s definition of a straight line as a li ne of

sight was suggested to me by David Pierce and supported by Alexander

Jones. See a detailed discussion of “straightness” in a book by David

Henderson and Dain a Taimina [32, Chapter 1].

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

11 Pedagogical Intermission:Nomination and Definition 127

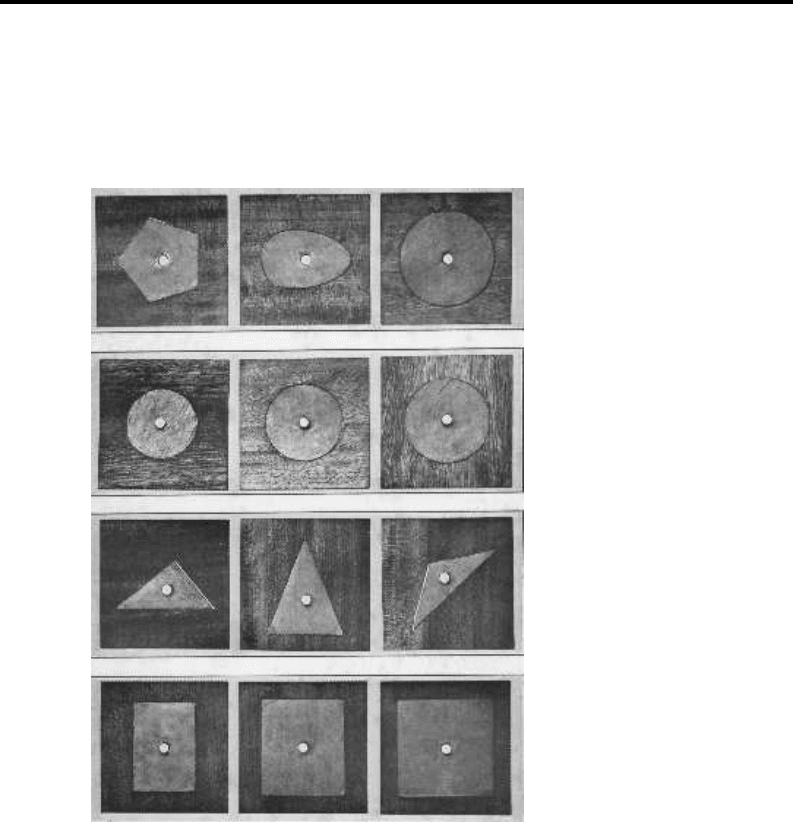

triangle, square, circle, etc. and c omparing them by placing shapes

into similarly shaped (but perhaps differently oriented) pockets

in a board, Figure 11.2. Nomenclature is a key component of the

Montessori Method.

Fig. 11.2. Insets of geometrical shapes, as used by Maria Montessori (18 70

– 1952) [696].

It is important to emphasize that not o nly vision, but also loco-

motor and tactile sensory systems were engaged in this exercise—

Radzivilovsky trained his children to recognize and name shapes

with eyes closed.

Perhaps, I would suggest introducing a name for an even more

elementary didactic act: pointing, like pointing a fin ger at a thing

before naming it.

A teacher dealing with a mathematically p erceptive child should

point to interesting mathematical objects; if a child is prepared to

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

128 11 Pedagogical Intermission:Nomination and Definition

grasp the object and play with it, a name has to be introduced—

and, in m ost cases, there is no need to rush ahead and introduce

formal definitions.

But, of course, one has to remember that names should relate

to things, since, using semiotics terminology, there is no signifier

without signified. Use of uprooted terms, torn away from any con-

text, can disorient not o nly a child, but a mature learner. To that

effect, read a te stimony from CW

6

:

For me, math s was always easy, until I came to two su bjects in

my undergraduate courses: ring theory and category theory. With

these I simply could not remember all the names of the different

types of things.

I’m not a stamp collector, I’m a model maker. I coul d cope with

the theory, but when someone said —“Consider a Noetherian ring

such that . . . ” I was lost. I couldn’t remember—still can’t—what a

Noetherian ring might be. Using the name lost me every time.

There was no problem with the maths itself, it was the use of

names as labels that lost me. I could do th e work, I couldn’t work

out what the work was to do.

Once I realized that I had trouble in remembering names for

things, I then turned it into a tool. Naming things is an incredibly

important action, so there were several occasions when I specifi-

cally put it to use. How? As follows.

When discussing a problem with colleagues we would offer a

definition, then make up a random name for it.

“Consider a disk with three holes and a point removed

from its boun d ary. We call this a Wunkle.”

“Consider a Wunkle with two intervals in the interior

identified. Call this a R issmuck.”

and so on. Every time we defined something new we would see if

it was a refinement of a previous item, and then name it. There

were so many names that some concepts got different names, and

we were constantly referring to the definitions and their names.

However, after some months of working on the same problem

we found that the important concepts corresponded to the remem-

bered names. Concepts whose names were not remembered turned

out to be less important. It was as if, and perhaps it really was,

that the linguistic process of remembering the name was itself

finding the important concepts for us.

6

CW is ma le, Britis h, has a Ph.D. in Pure Maths (graph theory and com-

binatorics).

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

12

The Towers of Hanoi and Binary Trees

Ritchie Flick

I think I was 9 or so, and I found the problem: “The tower of

Hanoi”. I think it was at a pu z z le shop or something like that. On

the product description, there was the formula for the puzzle and

I didn’t understand a single word at that time and the fact that it

was in French didn’t make things better (my mother language is

Luxembourgish).

When I was trying to ask some of my teachers at that time, I

couldn’t find anybody who could explain it to me.

For some reason, I remembered this story, and I finally inves-

tigated again the “The tower of Hanoi” a nd now, after 10 years, I

finally understand the formula of back then.

129

13

Mathematics of Finger-Pointing

13.1 John Baez: a taste of lambda calculus

The mathematician and theoretical physicist John Baez is famous

for his w ebsite This Week’s Finds in Mathematical Phys ics [2]. For

those not in the know: the first entry there appeared in 1993, this

website was one of the earliest and influe ntial precursors of the

blog movement. His Week 240 contains a cute introduction to the

area of mathematics called lambda ca lculus. It is important in the

context of this book bec ause it demonstrates one of the most re-

markable powers of mathematics: capacity for explicating, in pre-

cise mathematical ter ms, of informal co ncepts and procedures of

mathematical practice.

1

Indeed , some basic concepts of the lambda

calculus explicate a basic act of mathematical thinking: pointing

a finger at a mathematical object from a variety of similar objects

and saying:

“Let’s take this one”.

But, instead of giving my own explanations, I prefer to reproduce

verbatim a long quote from John Baez—with his kind permission:

Let’s play a game. I have a set X in my pocket, and I’m not telling

you what it is. Can you pick a n element of X in a systematic way?

2

No, of course not: you don’t have enough information. X could

even be empty, in which case you’re clearly doomed! But even if it’s

nonempty, if you don’t know anything about it, you can’t pick an

element in a systematic way.

So, you lose.

Okay, let’s play another game. Can you pick an element of

1

Week 2 40 post (http://math.ucr.edu/home/baez/week240.html)

is based on recent work by James Dolan an d Todd Trimble; it covers

much more than one of i ts more elementary fragment used in my book.

2

In my naive terminology, this means pointing finger at an el ement in

the set.—AB

131

132 13 M athematics of Finger-Pointing

X

X

in a systematic way? Here A

B

means the set of functi ons from B

to A. So, I’m asking if you can pick a function from X to itself in a

systematic way.

Yes! You can pick the identity function! This sends each ele-

ment of X to itself:

x 7→ x.

You don’t need to know anything about X to des cri be this function.

X can even be empty.

So, you win.

Are there any other ways to win? No.

Now let’s play another game. Can you pick an element of

X

(

X

X

)

in a systematic way?

An element in here takes functions from X to itself and turns

them into elements of X. When X is the set of real numbers, peo-

ple call this sort of thing a “functional”, so let’s use that term. A

functional eats functions and spits out elements.

You can scratch your head for a while trying to dream up a

systematic way to pick a functional for any set X. But, there’s no

way.

So, you lose.

Let’s play another game. Can you pick an element of

X

X

(

X

X

)

in a systematic way?

An element in here eats functions and spits out functions.

When X is the set of real numbers, people often call this sort of

thing an “operator”, so l et’s use that term.

Given an unknown set X, can you pick an operator in a system-

atic way? Sure! You can pick the identi ty operator. This operator

eats any function from X to itself and spits out the same function:

f 7→ f.

Anyway: you win.

Are there any other ways to win? Yes! There’s an operator that

takes any function and spits out the identity function:

f 7→ (x 7→ x).

This is a bit funny-looking, but I hope you get what it means : you

put in any function f, and out pops the identity function x 7→ x.

This arrow notation is very powerful. It’s usually called the

“lambda calcu lus”, since when Church invented it in the 1930s, he

wrote it using the Greek letter l ambda instead of an arrow: instead

of

x 7→ y

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

13.2 Here it is 133

he wrote

λx.y.

But this just makes things more confusing, so let’s not do it.

Are there more ways to win this game? Yes! Th ere’s also a n

operator called “squaring”, which takes any function f from X to

itself and "squares" it—in other words, does it twice. If we write

the result as f

2

, this operator is

f 7→ f

2

But, we can express this operator without us ing any special sym-

bol for squaring. The function f is the same as the function

x 7→ f(x)

so the fun ction f

2

is the same as

x 7→ f(f(x))

and the operator “squaring” is the same as

f 7→ (x 7→ f(f(x))).

This looks pretty complicated. But, it shows that our systematic

way of choosing an element of

X

X

(

X

X

)

can still be expressed using ju st the lambda calculus.

Now that you know “squaring” is a way to win this particular

game, you’ll immediately guess a bunch of other ways: “cubing”,

and so on. It turns out all the winning strategies are of this form!

We can list them all using the lambda calculus:

f 7→ (x 7→ x)

f 7→ (x 7→ f (x))

f 7→ (x 7→ f (f(x)))

f 7→ (x 7→ f (f(f(x))))

etc. Note that the second one is just a longer name for the identity

operator. The longer name makes the pa ttern clear.

Notice that this recursive construction of operators, gives us a

way to construct, within lambda calculus, natural numbers. Finger-

pointing leads to counting!

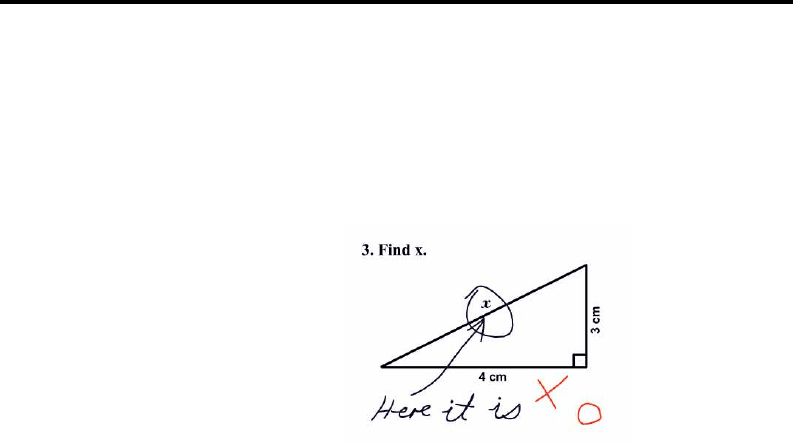

13.2 Here it is

Now let us listen to some former children. Here is a testimony from

Alan Hutchinson

3

:

3

AH is male, British, a lecturer in computer science at an university.

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK

134 13 M athematics of Finger-Pointing

(Age 9?) First exposure to algebra: I would write “x, where x is the

answer” because I did not understand the questions. It distressed

me.

The following is a piece of mathematical folklore floating all over

the Internet and blogosphere, claimed to be taken from an actual

student’s work:

The reader would probably agree that this solution “by fin ger

pointing” is suspiciously close to the principle s of lambda calculus.

The student, by inexperie nce, made a shortcut fr equently (and also

knowingly and deliberately) taken by mathematicians.

When I was an undergraduate studen t, I was lucky that the

teacher of my tutorials class in analysis was Semen Kutateladze—

I quoted him in Chapter 11. At that time, he was a m ildly eccentric

young man who loved to conduct his classes while r eclining on a

desk and smoking a pipe; he was a Bourbakist and an expert in

functional analysis. Kutateladze told us in the first class, with an

obvious disgust:

“Apparently yo u expect me to teach you to evaluate integrals?”

“No, we don’t—responded we reassuringly—we did that last

year”.

“Oh great! In that case we better do the real stuff. You know, I

hate that brainless c alculus”.

“But perhaps, in your work, you occasionally have to evaluate

an integral?”

“Of course, I do them every day—that way: if I have to integrate

a fun ction f with respect to a Lebesgue me asure µ, I write . . . ”—

and he wrote on the blackboard:

Z

fdµ.

Taking both answers, the student’s and my teacher’s, at their face

value, do you see a difference? I have to admit that I no longer do. I

wish to re c ord that as a question for researchers in methodology of

mathematics education: indeed , what is the difference between the

two responses?

SHADOWS OF THE TRUTH VER. 0.813 23-DEC-2010/7:19

c

ALEXANDRE V. BOROVIK