Biermann Ch. Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

614 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

while not as heavy, has been substituted for hard

maple in the better grades, particularly for furni-

ture.

Maple is used principally for lumber, veneer,

crossties, and pulpwood. A large proportion is

manufactured into flooring, furniture, boxes,

pallets and crates, handles, woodenware, novel-

ties,

spools, and bobbins.

Color. The sapwood of the maples is com-

monly white with a slight reddishbrown tinge. It

is from 3 to 5 or more inches thick. The heart-

wood is usually light reddish brown, but some-

times it is considerably darker. The annual rings

are not very distinct; they are defined by an

indistinct, darker line of marginal parenchyma

intermixed with fibers.

Macroscopic features. Maples are diffuse

porous woods, and the pores are not visible on any

surface without magnification. The vessels are

solitary (sometimes in radial muhiples of 2 to 3)

and evenly distributed within the growth ring.

Tyloses are normally absent.

Rays are visible. Hard maple is distinguished

from soft maple by the two distinct ray sizes of

hard maple (which may be up to 8—seriate and as

wide as the widest pores) and a lustrous appear-

ance.

The rays of soft maples vary in size, the

widest of which is almost the same width as the

widest vessels (about 5—seriate). Saturated FeS04

in water turns red maple blue—black but gives a

green color with sugar maple. Parenchyma are

not seen with a lens.

Microscopic features. Longitudinal parenchy-

ma are marginal, defining growth ring boundaries

and intermixed with fibers. Intervessel pitting of

red maple is alternate, angular in outline, and

crowded. The vessels of soft maple are longer

than those of hard maple, whose lengths are

seldom more than about three times their diameter.

Similar

woods.

Maples (simple vessel perfo-

ration plates) are distinguished from birches

(sclariform perforation plates). The rays of

birches are not distinct to the unaided eye, while

the vessels are distinct. The rays of beech are

much wider than the vessels (x).

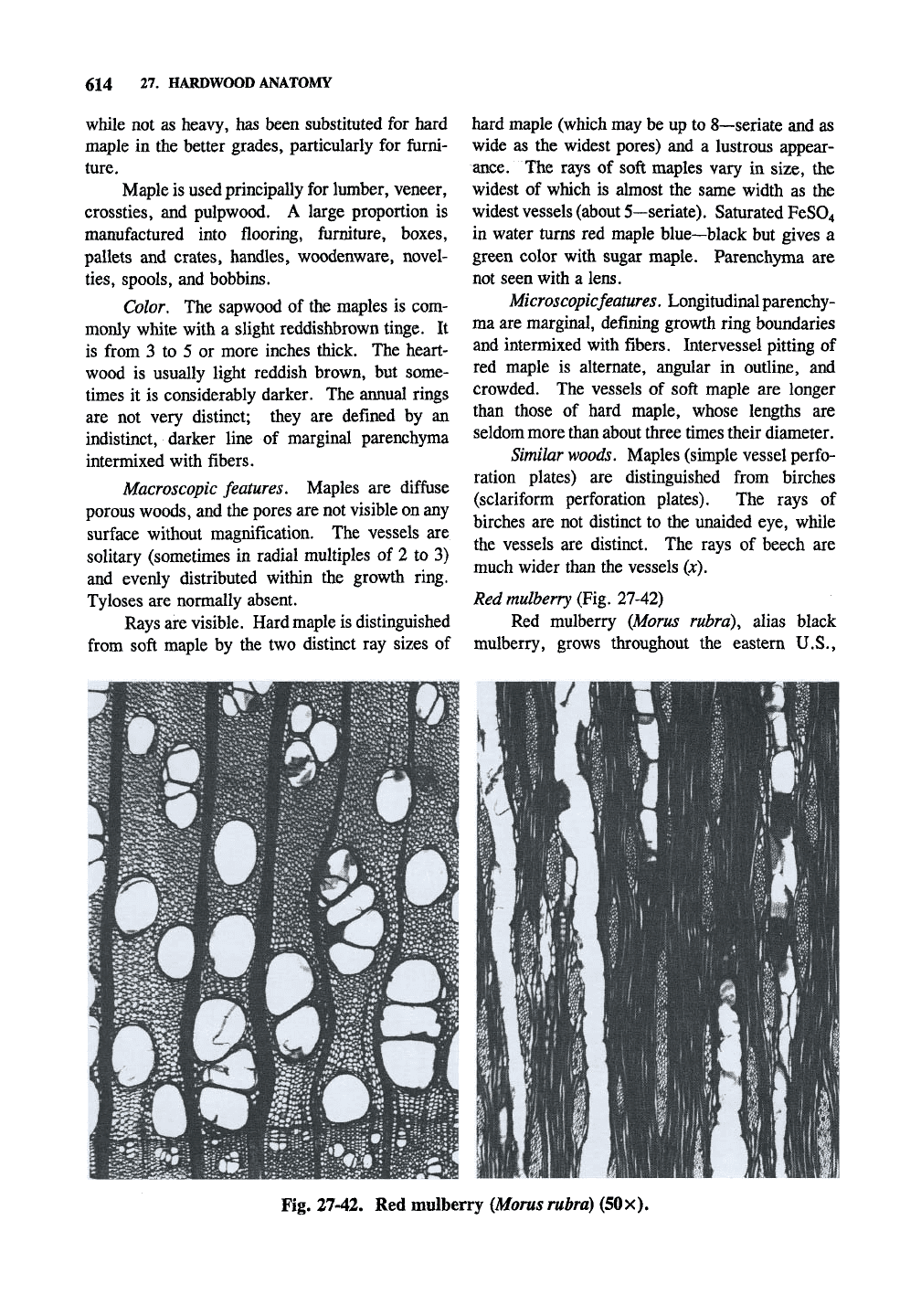

Red

mulberry

(Fig. 27-42)

Red mulberry (Morus rubra), alias black

mulberry, grows throughout the eastern U.S.,

Fig. 27-42. Red mulberry (Moms

rubra)

(50x).

ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECIES 615

except in New England. The wood is heavy,

straight grained. The growth rings are distinct and

usually moderately wide.

Color. The sapwood is yellowish and about

0.5 in. wide. The heartwood is yellowish brown

on freshly cut surfaces, turning to russet brown

with exposure to air.

Macroscopic structure. The wood is ring-

porous. The earlywood pores are large, distinct,

and form a ring of 2—5 pores width. They are

densely packed with tyloses that have a unique

glistening appearance. The latewood pores form

small irregular (nestlike) groups of 3—10 often

forming wavy, tangential bands that are observed

without a lens. The rays are evident without a

lens and form flecks on the radial surfaces. The

parenchyma are observed with a lens.

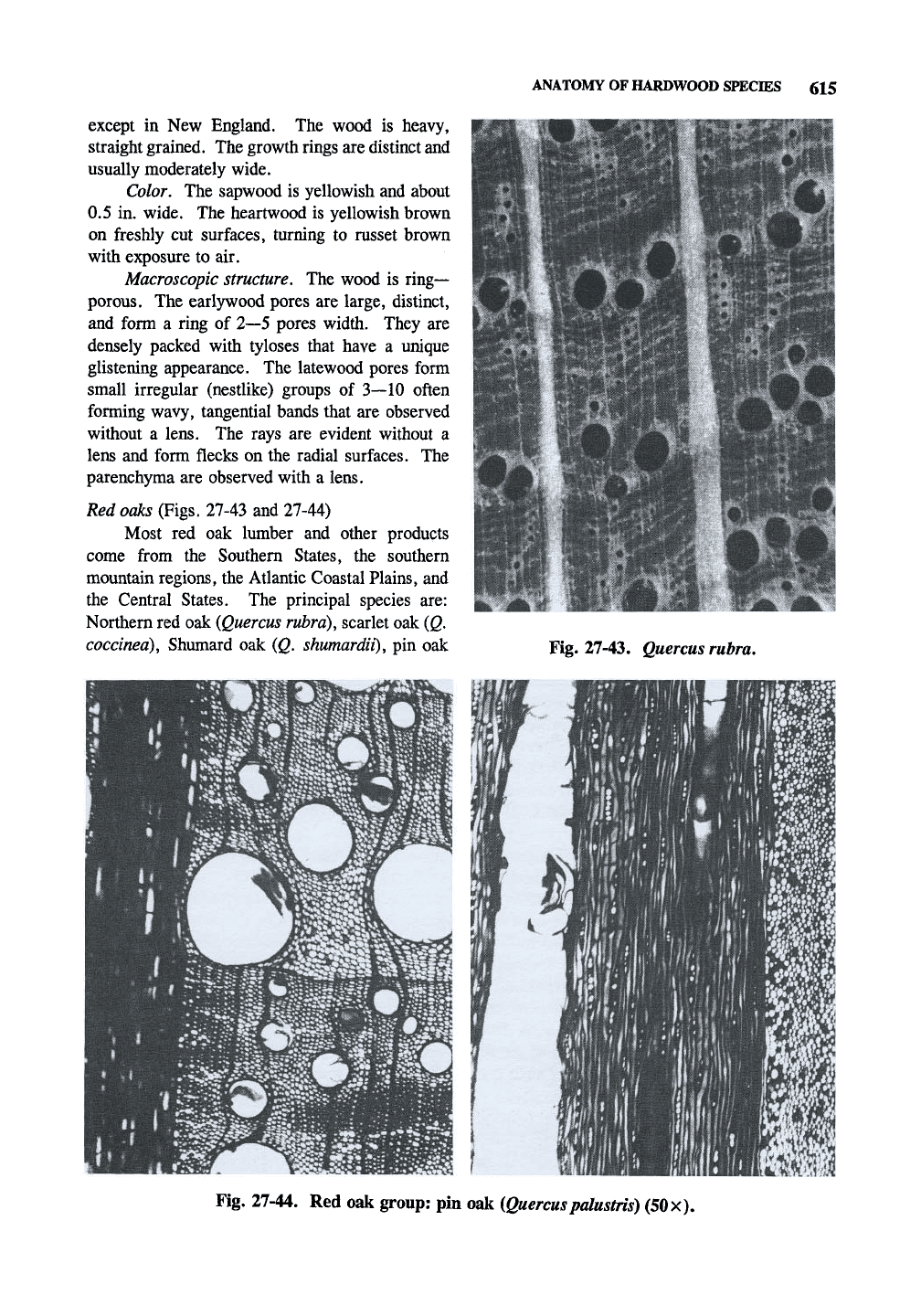

Red oaks (Figs. 27-43 and 27-44)

Most red oak lumber and other products

come from the Southern States, the southern

mountain regions, the Atlantic Coastal Plains, and

the Central States. The principal species are:

Northern red oak

{Quercus

rubra), scarlet oak (Q.

coccinea),

Shumard oak {Q. shumardii), pin oak

Fig. 27-43.

Quercus

rubra.

Fig. 27-44. Red oak group: pin oak (Quercuspalustris) (50

x).

616 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

(Q, palustris), Nuttall oak

(Q.

nuttallii), black oak

{Q, velutina), southern red oak {Q. falcata),

cherrybark oak (Q. falcata var. pagodaefolia),

water oak (Q. nigra), laurel oak (Q. laurifolia),

and willow oak

{Q,

phellos).

Uses, Wood of the red oaks is heavy.

Rapidly grown second—growth oak is generally

harder and tougher than finer textured old—growth

timber. The red oaks have fairly large shrinkage

in drying. The red oaks are largely cut into

lumber, railroad ties, mine timbers, fence posts,

veneer, pulpwood, and fuelwood. Ties, mine

timbers, and fence posts require preservative

treatment for satisfactory service. Quartersawn

lumber is distinguished by the broad and conspicu-

ous rays, which add to its attractiveness. Red oak

lumber is remanufactured into flooring, furniture,

general millwork, boxes, pallets and crates,

caskets, woodenware, and handles.

Color. The sapwood is nearly white and

usually 1 to 2 inches thick. The heartwood is

brown with a tinge of red.

Macroscopic features. The red oaks are

ring—porous, but may be more semi—ring-

porous than the white oaks. The earlywood

vessels form two or three rows (or four in wide

growth rings). Latewood vessels have a dendritic

arrangement (groups that are oblique or in a group

that widens toward the outer limit of the growth

ring) and are surrounded by paratracheal paren-

chyma. Individual vessels are solitary, rounded,

sparsely distributed, and have thick walls.

Rays are either uniseriate or extremely broad

of the type characteristic of oaks. Longitudinal

parenchyma are abundant as paratracheal and

apotracheal banded parenchyma. Tyloses are

usually absent to sparse.

Similar woods. Sawed lumber of red oaks

cannot be separated by species on the basis of the

characteristics of the wood alone. Red oak lumber

can be separated from white oak by the number of

pores in the latewood and, as a rule, it lacks

tyloses in the pores. The open pores of the red

oaks make these species unsuitable for tight coo-

perage, unless the wood is sealed.

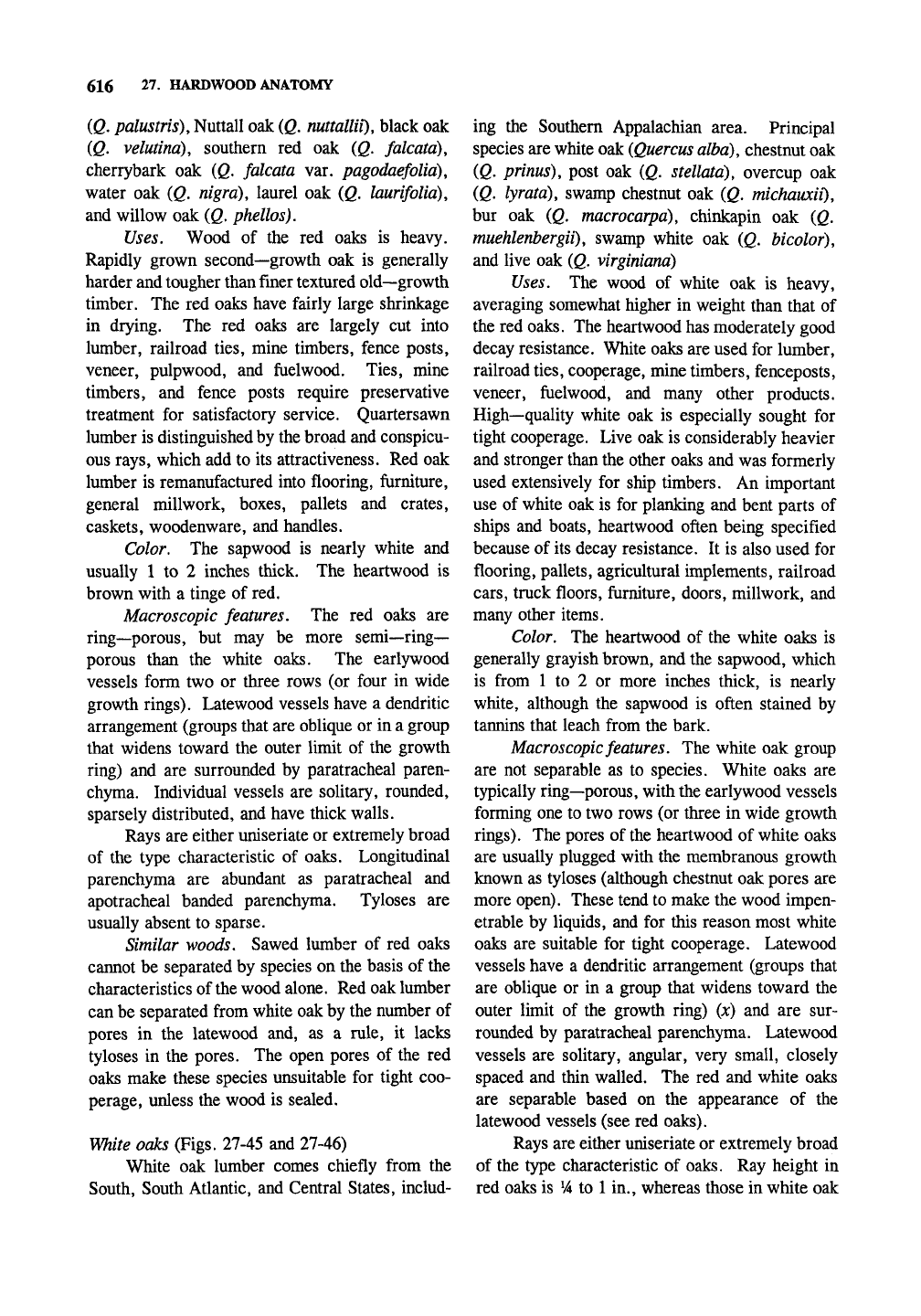

Wiite oaks (Figs. 27-45 and 27-46)

White oak lumber comes chiefly from the

South, South Atlantic, and Central States, includ-

ing the Southern Appalachian area. Principal

species are white oak

(Quercus

alba), chestnut oak

{Q. prims), post oak (Q. stellata), overcup oak

{Q. lyrata), swamp chestnut oak {Q. michauxii),

bur oak (Q. macrocarpa), chinkapin oak (Q.

muehlenbergii), swamp white oak {Q. bicolor),

and live oak

{Q.

virginiana)

Uses. The wood of white oak is heavy,

averaging somewhat higher in weight than that of

the red oaks. The heartwood has moderately good

decay resistance. White oaks are used for lumber,

railroad ties, cooperage, mine timbers, fenceposts,

veneer, fuelwood, and many other products.

High—quality white oak is especially sought for

tight cooperage. Live oak is considerably heavier

and stronger than the other oaks and was formerly

used extensively for ship timbers. An important

use of white oak is for planking and bent parts of

ships and boats, heartwood often being specified

because of its decay resistance. It is also used for

flooring, pallets, agricultural implements, railroad

cars,

truck floors, ftirniture, doors, millwork, and

many other items.

Color. The heartwood of the white oaks is

generally grayish brown, and the sapwood, which

is from 1 to 2 or more inches thick, is nearly

white, although the sapwood is often stained by

tannins that leach from the bark.

Macroscopic features. The white oak group

are not separable as to species. White oaks are

typically ring—porous, with the earlywood vessels

forming one to two rows (or three in wide growth

rings).

The pores of the heartwood of white oaks

are usually plugged with the membranous growth

known as tyloses (although chestnut oak pores are

more open). These tend to make the wood impen-

etrable by liquids, and for this reason most white

oaks are suitable for tight cooperage. Latewood

vessels have a dendritic arrangement (groups that

are oblique or in a group that widens toward the

outer limit of the growth ring) (x) and are sur-

rounded by paratracheal parenchyma. Latewood

vessels are solitary, angular, very small, closely

spaced and thin walled. The red and white oaks

are separable based on the appearance of the

latewood vessels (see red oaks).

Rays are either uniseriate or extremely broad

of the type characteristic of oaks. Ray height in

red oaks is

V4

to 1 in., whereas those in white oak

ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECIES 617

may be 0.5 to 5 in. high,

paratracheal and apotracheal.

Parenchyma are

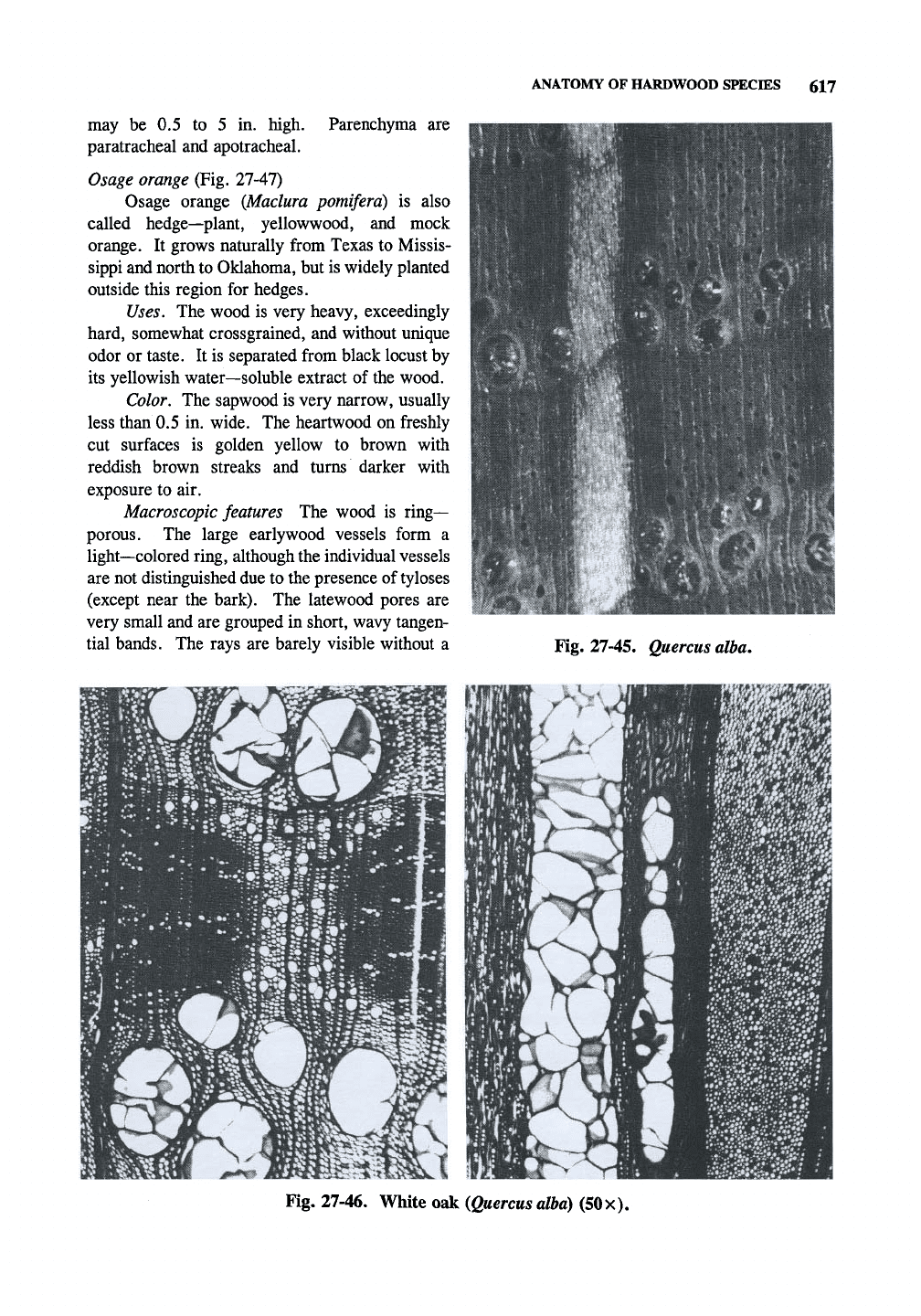

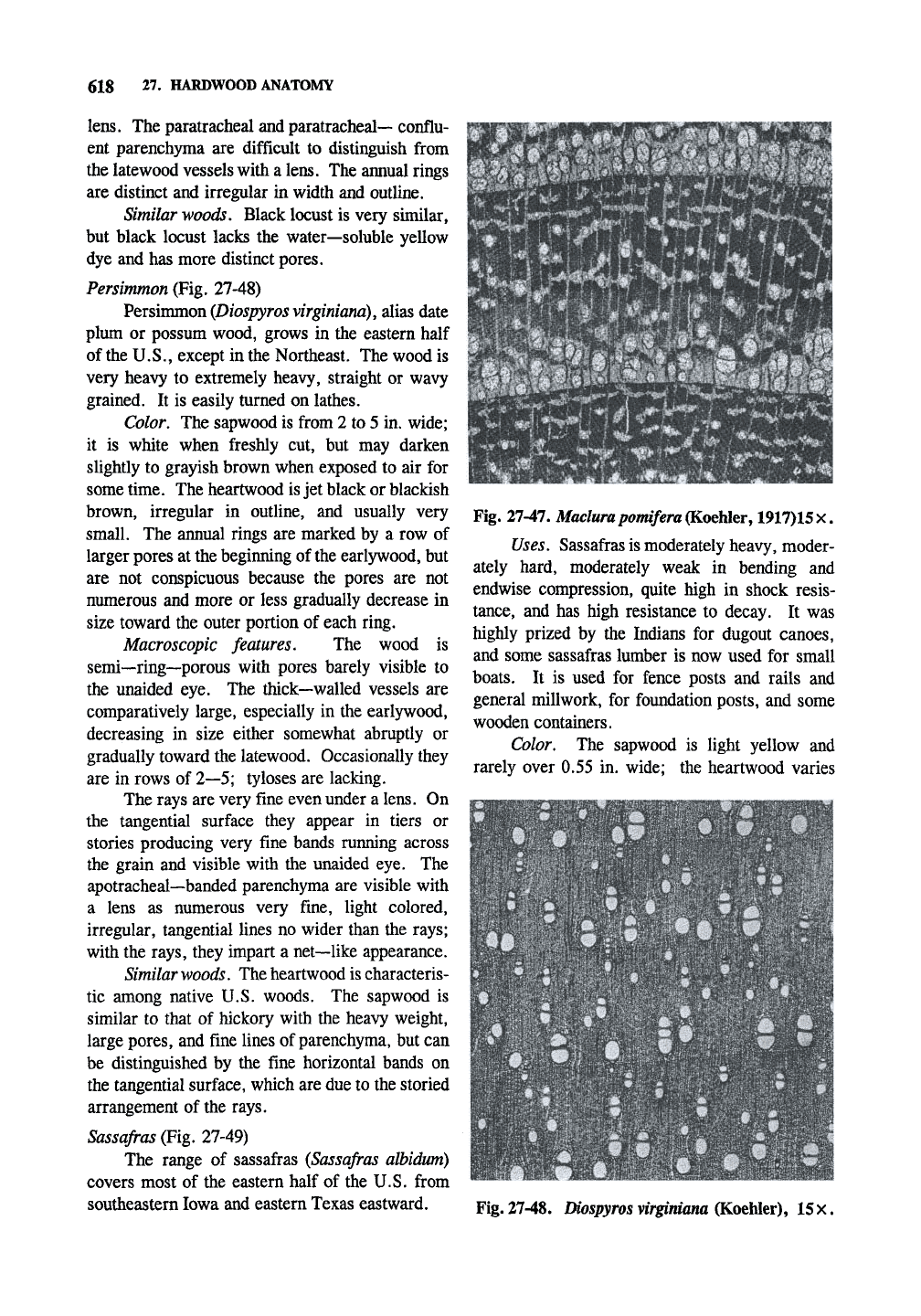

Osage orange (Fig. 27-47)

Osage orange {Madura pomifera) is also

called hedge—plant, yellowwood, and mock

orange. It grows naturally from Texas to Missis-

sippi and north to Oklahoma, but is widely planted

outside this region for hedges.

Uses. The wood is very heavy, exceedingly

hard, somewhat crossgrained, and without unique

odor or taste. It is separated from black locust by

its yellowish water—soluble extract of the wood.

Color. The sapwood is very narrow, usually

less than 0.5 in. wide. The heartwood on freshly

cut surfaces is golden yellow to brown with

reddish brown streaks and turns darker with

exposure to air.

Macroscopic features The wood is ring-

porous. The large early wood vessels form a

light—colored ring, although the individual vessels

are not distinguished due to the presence of tyloses

(except near the bark). The latewood pores are

very small and are grouped in short, wavy tangen-

tial bands. The rays are barely visible without a

Fig. 27-45.

Quercus

alba.

Fig. 27-46. White oak

{Q^ercus alba) (50

x).

618 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

lens.

The paratracheal and paratracheal— conflu-

ent parenchyma are difficult to distinguish from

the latewood vessels with a lens. The annual rings

are distinct and irregular in width and outline.

Similar woods. Black locust is very similar,

but black locust lacks the water—soluble yellow

dye and has more distinct pores.

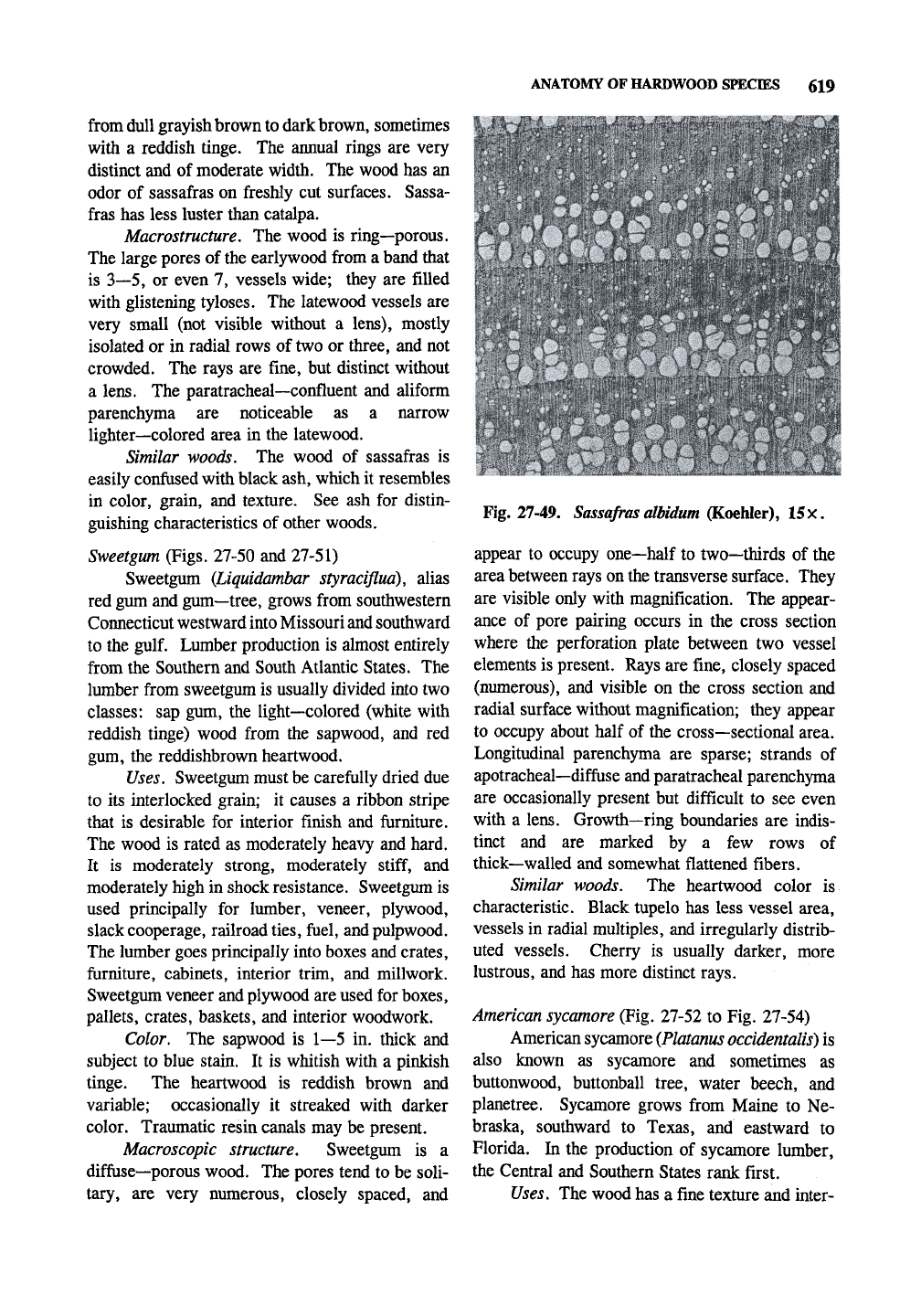

Persimmon (Fig. 27-48)

Persinmion

{Diospyros

virginiana),

alias date

plum or possum wood, grows in the eastern half

of the U.S., except in the Northeast. The wood is

very heavy to extremely heavy, straight or wavy

grained. It is easily turned on lathes.

Color, The sapwood is from 2 to 5 in. wide;

it is white when freshly cut, but may darken

slightly to grayish brown when exposed to air for

some time. The heartwood

is

jet black or blackish

brown, irregular in outline, and usually very

small. The annual rings are marked by a row of

larger pores at the beginning of

the

earlywood, but

are not conspicuous because the pores are not

numerous and more or less gradually decrease in

size toward the outer portion of each ring.

Macroscopic features. The wood is

semi—ring—porous with pores barely visible to

the unaided eye. The thick—walled vessels are

comparatively large, especially in the earlywood,

decreasing in size either somewhat abruptly or

gradually toward the latewood. Occasionally they

are in rows of

2—5;

tyloses are lacking.

The rays are very fme even under a lens. On

the tangential surface they appear in tiers or

stories producing very fme bands running across

the grain and visible with the unaided eye. The

apotracheal—banded parenchyma are visible with

a lens as numerous very fme, light colored,

irregular, tangential lines no wider than the rays;

with the rays, they impart a net—like appearance.

Similar

woods.

The heartwood is characteris-

tic among native U.S. woods. The sapwood is

similar to that of hickory with the heavy weight,

large pores, and fme lines of parenchyma, but can

be distinguished by the fme horizontal bands on

the tangential surface, which are due to the storied

arrangement of the rays.

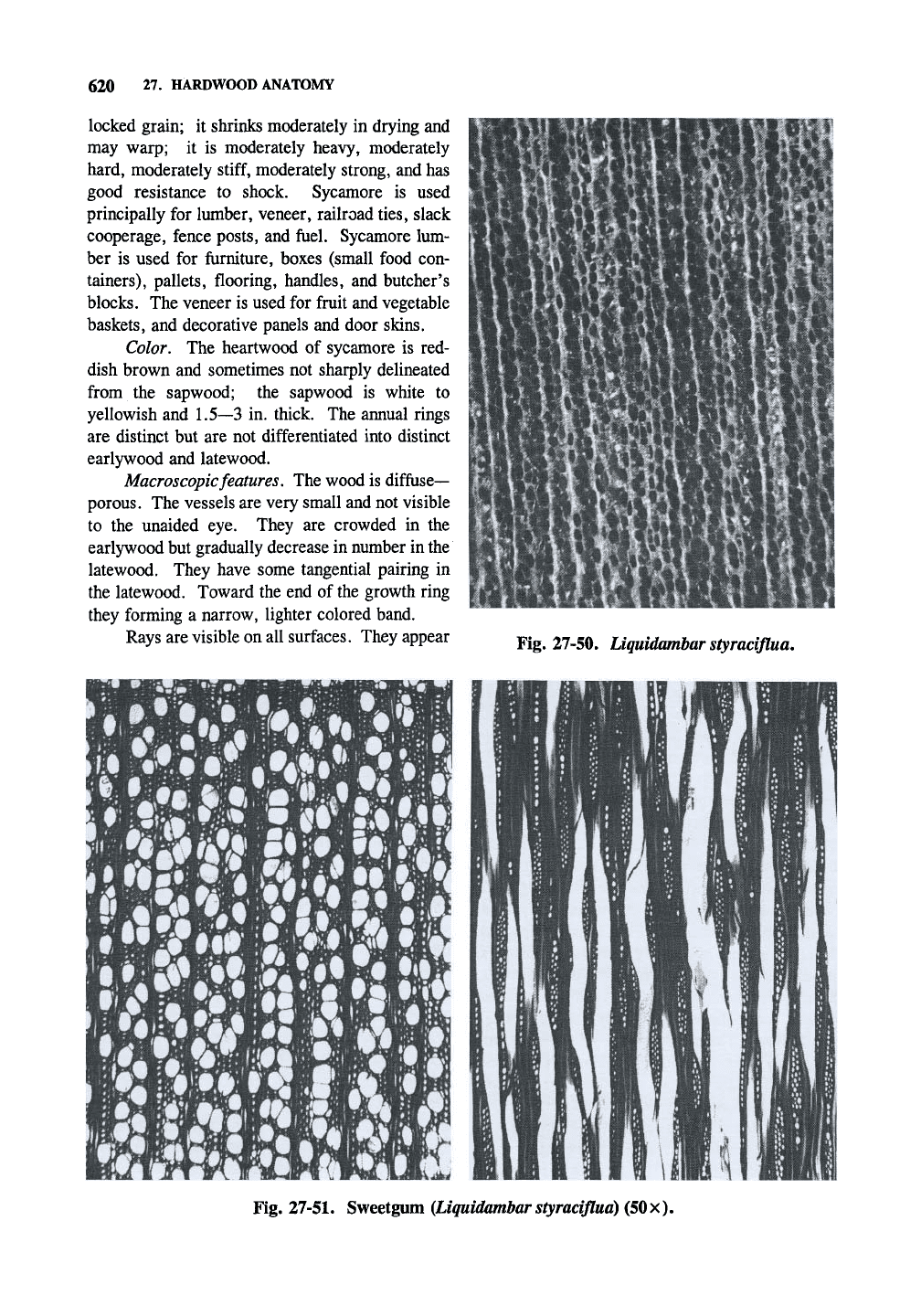

Sassafras (Fig. 27-49)

The range of sassafras (Sassafras albidum)

covers most of the eastern half of the U.S. from

southeastern Iowa and eastern Texas eastward.

Mmmmm¥':

Fig. 27-47.

Maclurapomifera

(Koehler,

1917)15 X.

Uses. Sassafras is moderately heavy, moder-

ately hard, moderately weak in bending and

endwise compression, quite high in shock resis-

tance, and has high resistance to decay. It was

highly prized by the Indians for dugout canoes,

and some sassafras lumber is now used for small

boats.

It is used for fence posts and rails and

general millwork, for foundation posts, and some

wooden containers.

Color. The sapwood is light yellow and

rarely over 0.55 in. wide; the heartwood varies

Fig. 27-48. Diospyros virgimana (Koehler), 15 x.

ANATOMY

OF

HARDWOOD SPECIES

619

from dull grayish brown to dark

brown,

sometimes

with

a

reddish tinge.

The

annual rings

are

very

distinct

and of

moderate width.

The

wood

has an

odor

of

sassafras

on

freshly

cut

surfaces. Sassa-

fras

has

less luster than catalpa.

Macrostructure,

The

wood

is

ring—porous.

The large pores

of

the earlywood from

a

band that

is

3—5, or

even

7,

vessels wide; they

are

filled

with glistening tyloses.

The

latewood vessels

are

very small

(not

visible without

a

lens), mostly

isolated

or in

radial rows

of

two

or

three,

and not

crowded.

The

rays

are

fine,

but

distinct without

a lens.

The

paratracheal—confluent

and

aliform

parenchyma

are

noticeable

as a

narrow

lighter—colored area

in the

latewood.

Similar woods.

The

wood

of

sassafras

is

easily confused with black ash, which

it

resembles

in color, grain,

and

texture.

See ash for

distin-

guishing characteristics

of

other woods.

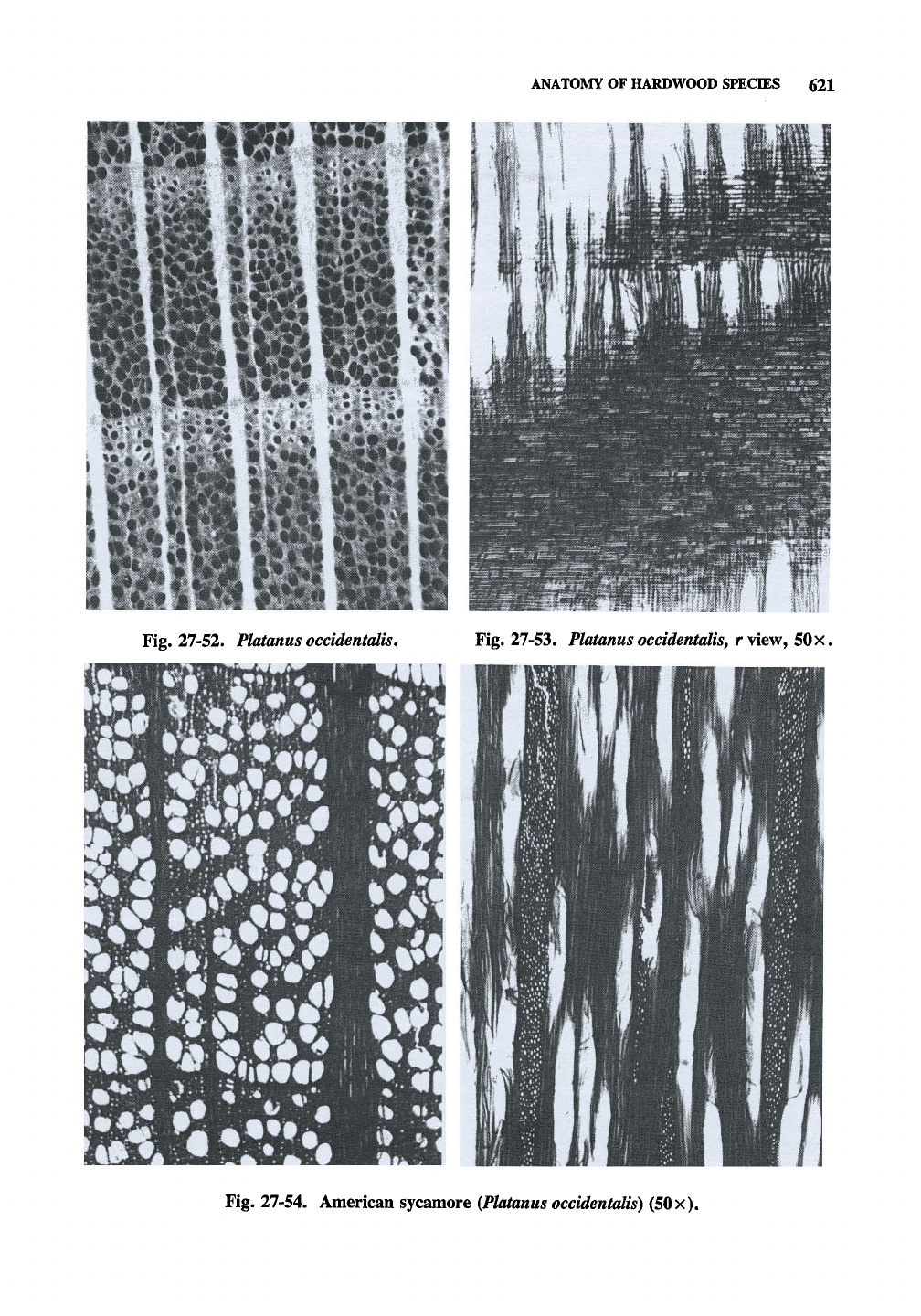

Sweetgum (Figs. 27-50

and

27-51)

Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua), alias

red gum

and

gum—tree, grows from southwestern

Connecticut westward into Missouri and southward

to

the gulf.

Limiber production

is

almost entirely

from

the

Southern

and

South Atlantic States.

The

lumber from sweetgum

is

usually divided into

two

classes:

sap gum, the

light—colored (white with

reddish tinge) wood from

the

sapwood,

and red

gum,

the

reddishbrown heartwood.

Uses. Sweetgum must be carefully dried

due

to

its

interlocked grain;

it

causes

a

ribbon stripe

that

is

desirable

for

interior finish

and

furniture.

The wood

is

rated

as

moderately heavy

and

hard.

It

is

moderately strong, moderately

stiff, and

moderately high

in

shock resistance. Sweetgum

is

used principally

for

lumber, veneer, plywood,

slack cooperage, railroad ties, fuel, andpulpwood.

The lumber goes principally into boxes and crates,

furniture, cabinets, interior trim,

and

millwork.

Sweetgum veneer and plywood are used

for

boxes,

pallets, crates, baskets,

and

interior woodwork.

Color.

The

sapwood

is 1—5 in.

thick

and

subject

to

blue stain.

It is

whitish with

a

pinkish

tinge.

The

heartwood

is

reddish brown

and

variable; occasionally

it

streaked with darker

color. Traumatic resin canals

may be

present.

Macroscopic structure. Sweetgxmi

is a

diffuse—porous wood.

The

pores tend

to be

soli-

tary,

are

very numerous, closely spaced,

and

Fig. 27-49.

Sassafras albidum

(Koehler), 15 x.

appear

to

occupy one—half

to

two—thirds

of the

area between rays on the transverse surface. They

are visible only with magnification.

The

appear-

ance

of

pore pairing occurs

in the

cross section

where

the

perforation plate between

two

vessel

elements

is

present. Rays

are

fine, closely spaced

(numerous),

and

visible

on the

cross section

and

radial surface without magnification; they appear

to occupy about half

of the

cross—sectional area.

Longitudinal parenchyma

are

sparse; strands

of

apotracheal—diffuse and paratracheal parenchyma

are occasionally present

but

difficult

to see

even

with

a

lens. Growth—ring boundaries

are

indis-

tinct

and are

marked

by a few

rows

of

thick—walled

and

somewhat flattened fibers.

Similar woods.

The

heartwood color

is

characteristic. Black tupelo

has

less vessel area,

vessels

in

radial multiples,

and

irregularly distrib-

uted vessels. Cherry

is

usually darker, more

lustrous,

and has

more distinct rays.

American sycamore (Fig. 27-52

to Fig.

27-54)

American sycamore

(Platanus occidentalis)

is

also known

as

sycamore

and

sometimes

as

buttonwood, buttonball tree, water beech,

and

planetree. Sycamore grows from Maine

to Ne-

braska, southward

to

Texas,

and

eastward

to

Florida.

In the

production

of

sycamore lumber,

the Central

and

Southern States rank first.

Uses.

The

wood has

a

fine texture

and

inter-

620 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

locked grain; it shrinks moderately in drying and

may warp; it is moderately heavy, moderately

hard, moderately

stiff,

moderately strong, and has

good resistance to shock. Sycamore is used

principally for lumber, veneer, railroad ties, slack

cooperage, fence posts, and fuel. Sycamore lum-

ber is used for furniture, boxes (small food con-

tainers), pallets, flooring, handles, and butcher's

blocks. The veneer is used for fruit and vegetable

baskets, and decorative panels and door skins.

Color. The heartwood of sycamore is red-

dish brown and sometimes not sharply delineated

from the sapwood; the sapwood is white to

yellowish and 1.5—3 in. thick. The annual rings

are distinct but are not differentiated into distinct

earlywood and latewood.

Macroscopic features. The wood is diffuse-

porous. The vessels are very small and not visible

to the unaided eye. They are crowded in the

earlywood but gradually decrease in number in the

latewood. They have some tangential pairing in

the latewood. Toward the end of the growth ring

they forming a narrow, lighter colored band.

Rays are visible on all surfaces. They appear

Fig. 27-50. Liquidambar styraciflua.

Fig.

27-51.

Sweetgum (Liquidambar styraciflua) (50X).

ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECIES 621

Fig. 27-52. Platanus occidentalis.

Fig. 27-53. Platanus

occidentalis,

rview, 50 x.

Fig. 27-54. American sycamore

(Platanus occidentalis)

(50x).

622 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

uniformly spaced on the cross section and of

uniform height on the radial surface. These rays

appear as "silver grain" on the radial surfaces.

The parenchyma are not visible even with a lens.

Other species. Sycamore is not easily con-

fused with other species. Its numerous conspicu-

ous rays and interlocked grain make it easily

recognizable. It is distinguished from beech by its

rays,

only a small proportion of which are broad

in beech. Beech also has a distinct darker and

denser band of latewood.

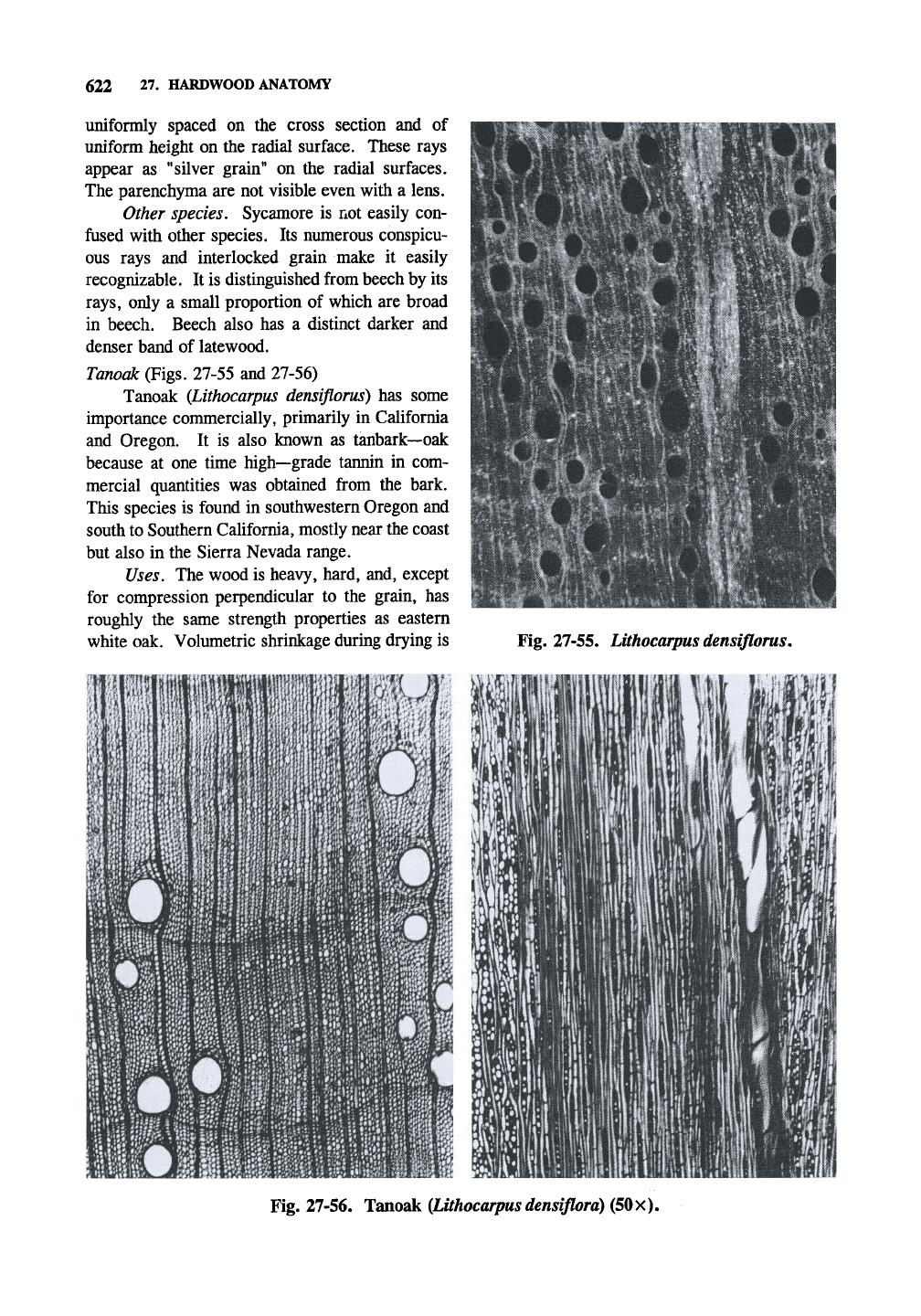

Tanoak (Figs. 27-55 and 27-56)

Tanoak {Lithocarpus densiflorus) has some

importance commercially, primarily in California

and Oregon. It is also known as tanbark~oak

because at one time high—grade tannin in com-

mercial quantities was obtained from the bark.

This species is found in southwestern Oregon and

south to Southern California, mostly near the coast

but also in the Sierra Nevada range.

Uses. The wood is heavy, hard, and, except

for compression perpendicular to the grain, has

roughly the same strength properties as eastern

white oak. Volumetric shrinkage during drying is

Fig. 27-55.

Lithocarpus

densiflorus.

Fig. 27-56. Tanoak

{Lithocarpus

densiflora) (50x).

ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECIES 623

more than for white oak, and it has a tendency to

collapse during drying. It is quite susceptible to

decay, but the sapwood takes preservatives and

stains easily. It has straight grain and machines

and glues well. Because of tanoak's hardness and

abrasion resistance, it is an excellent wood for

flooring in homes or commercial buildings. It is

suitable for industrial applications such as truck

flooring. Tanoak treated with preservative has

been used for railroad crossties. The wood has

been manufactured into baseball bats with good

results. It is also suitable for veneer, botii decora-

tive and industrial, and for high—quality furniture.

It is used in corrugating medium.

Color. The sapwood of tanoak is light

reddish brown when first cut and turns darker with

age to resemble the heartwood, which also ages to

dark reddish brown.

Macroscopic

features. The wood is semi-

ring—porous with a gradual transition in pore size.

The latewood vessels form oblique groups or

clusters. The apotracheal parenchyma are banded

and abundant. They are visible with a lens as

irregular wide lines. The rays are of two sizes;

the large rays are irregularly distributed.

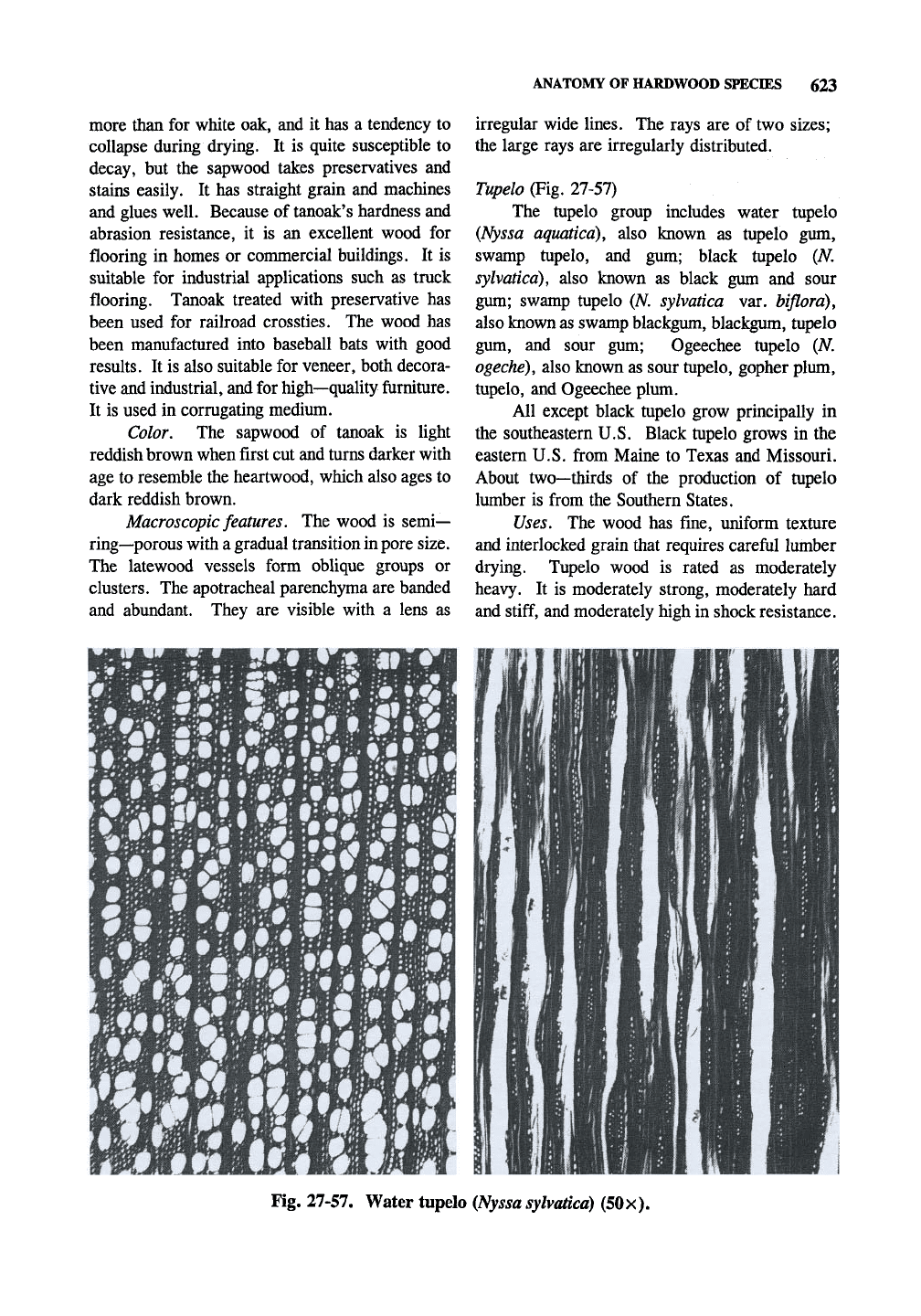

Tupelo (Fig. 27-57)

The tupelo group includes water tupelo

(Nyssa aquatica), also known as tupelo gum,

swamp tupelo, and gum; black tupelo (N.

sylvatica),

also known as black gum and sour

gum; swamp tupelo (N. sylvatica var. biflora),

also known

as

swamp blackgum, blackgum, tupelo

gum, and sour gum; Ogeechee tupelo (A^.

ogeche),

also known as sour tupelo, gopher plum,

tupelo, and Ogeechee plum.

All except black tupelo grow principally in

the southeastern U.S. Black tupelo grows in the

eastern U.S. from Maine to Texas and Missouri.

About two—thirds of the production of tupelo

lumber is from the Southern States.

Uses. The wood has fine, uniform texture

and interlocked grain that requires careful lumber

drying. Tupelo wood is rated as moderately

heavy. It is moderately strong, moderately hard

and

stiff,

and moderately high in shock resistance.

Fig. 27-57. Water tupelo

{Nyssa sylvatica)

(50x).