Biermann Ch. Handbook of Pulping and Papermaking

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

584

27.

HARDWOOD ANATOMY

samples. The diameter of vessels increases with

increasing growth ring width and distance from the

pith. Tropical woods tend to be diffuse porous.

The vessel diameters can be very small,

below 30 /xm; small, 30—100 fim; medium,

100—300 jLtm; and large, greater than 300 ^m.

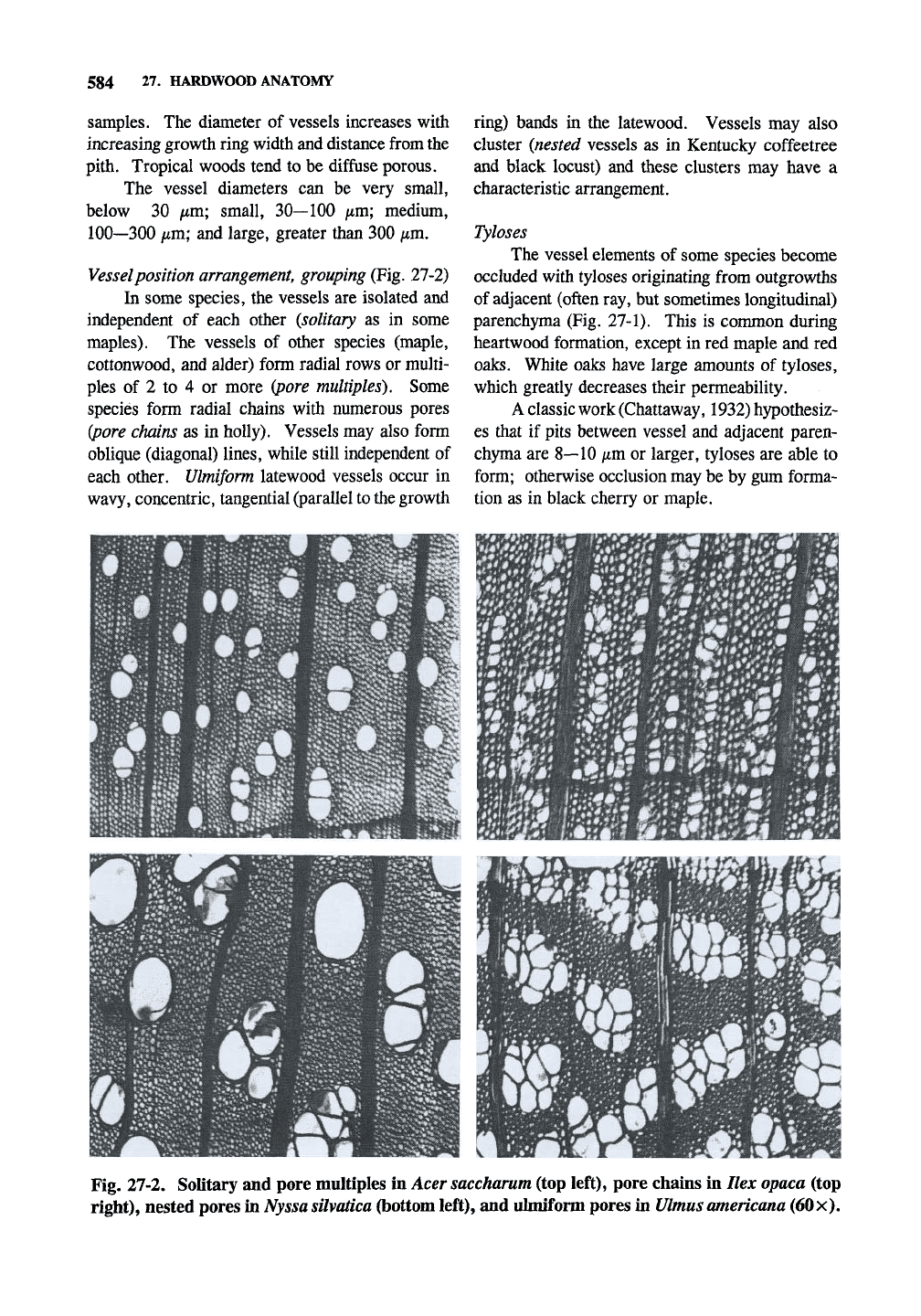

Vessel position

arrangement,

grouping (Fig. 27-2)

In some species, the vessels are isolated and

independent of each other {solitary as in some

maples). The vessels of other species (maple,

Cottonwood, and alder) form radial rows or multi-

ples of 2 to 4 or more {pore multiples). Some

species form radial chains with numerous pores

{pore chains as in holly). Vessels may also form

oblique (diagonal) lines, while still independent of

each other. Ulmiform latewood vessels occur in

wavy, concentric, tangential (parallel to the growth

ring) bands in the latewood. Vessels may also

cluster {nested vessels as in Kentucky coffeetree

and black locust) and these clusters may have a

characteristic arrangement.

Tyloses

The vessel elements of some species become

occluded with tyloses originating from outgrowths

of adjacent (often ray, but sometimes longitudinal)

parenchyma (Fig. 27-1). This is common during

heartwood formation, except in red maple and red

oaks.

White oaks have large amounts of tyloses,

which greatly decreases their permeability.

A classic work (Chattaway,

1932)

hypothesiz-

es that if pits between vessel and adjacent paren-

chyma are 8—10 ^m or larger, tyloses are able to

form; otherwise occlusion may be by gum forma-

tion as in black cherry or maple.

Fig. 27-2. Solitary and pore multiples in Acer

saccharum

(top left), pore chains in Ilex opaca (top

right),

nested pores in Nyssa

silvatica

(bottom left), and ulmiform pores in

Ulmus

americana (60

x).

GROSS ANATOMY OF HARDWOODS 585

Parenchyma cell arrangement {x)

Parenchyma cells are arranged longitudinally

{axial) or radially {ray). Axial parenchyma may

be rare or absent, but are generally present. The

longitudinal arrangement has been described by

Jane (1956, p. 115) based on work by Kribs in

1950.

Parenchyma cells are often visible as white

bands in hardwoods. Marginal (boundary) paren-

chyma are found in bands near the boundary of the

growth ring Plate 45-a. They may be terminal if

occurring in the latewood or initial if occurring in

the earlywood. Epithelial parenchyma surround

longitudinal gum canals in traumatic gum canals

(for example, in wounded sweetgum).

Apotracheal parenchyma are arranged inde-

pendently of the vessels. They may be dijfuse or

banded (forming groups of 2—4 or more cells

wide parallel to the growth rings). Lines of

banded parenchyma may form a net—like appear-

ance with rays known as reticulate parenchyma as

in hickory and persimmon (Plate 45-b).

If the parenchyma cells are arranged around

the vessels they are called paratracheal. If they

partially surround the vessels they are scanty; if

they form a partial band around the vessel all on

one side they are unilateral. They may totally

encircle the vessel {vasicentric, Plate 45-c) and

have lateral wings (aliform) or long lateral wings

that merge with each other (confluent).

Ray appearance

Oaks,

maples, and beeches contain rays that

are readily visible in all three views. Aggregate

rays consist of radial and longitudinal cells that are

intermixed and occur in addition to smaller rays

(red alder and American hornbeam). Storied rays

are a series of rays that each have the same height

and occur at the same height (in the tangential

view, t) (American mahogany). Some species

have rays that are not observed with a hand lens.

The ray width relative to vessel diameter, the

number of rays over a given area, and the percent-

age of cross—sectional area covered by rays are

three items that may be important. Some rays

expand at the growth ring boundary (x) in noded

rays [yellow poplar (Plate 45-a), beech, and

sycamore].

Large rays show as ray flecks (r).

Color

The heartwood of many hardwood species is

characteristic. Black walnut has a dark brown

heartwood; the color of black cherry varies from

light to deep brown with high luster; ebony is

almost black; yellow poplar heartwood has a

greenish cast with patches or streaks from red to

dark brown; the small black heartwood of persim-

mon resembles ebony, to which it is related; red

gum has a dingy, reddish brown color; buckeye

has a uniform creamy yellow color. Osage orange

is very similar to black locust, but the former

gives off a water—soluble yellowish dye when

extracted with water. A reference collection of

known species is useful for color comparisons.

Odor

Teak, sassafras, and Oregon myrtle have

distinctive odors. Bass wood (said to be like raw

potatoes) and catalpa (said to be like kerosene)

have odors that can be helpful in their identifica-

tion especially in freshly cut, green wood.

Fluorescence

Hoadley (1990) describes the fluorescence of

wood using longwave UV lamp sources. Among

U.S.

woods, this techniques is useful with mem-

bers of the Leguminosae family including black

locust (to separate it from osage—orange),

honeylocust, Kentucky coffeetree, and acacia.

Wood from Rhus and Ilex genera also fluoresce.

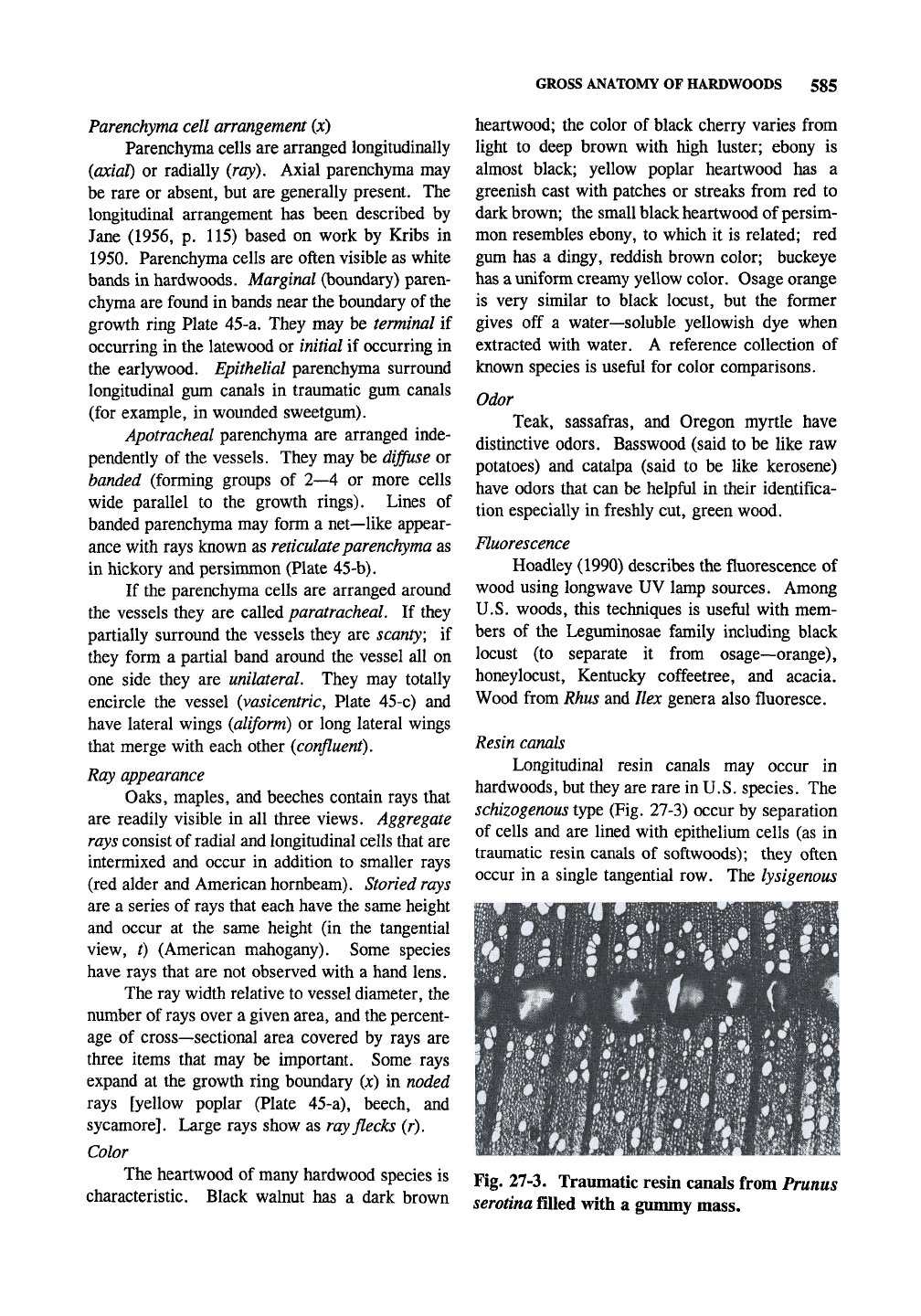

Resin canals

Longitudinal resin canals may occur in

hardwoods, but they are rare in U.S. species. The

schizogenous

type (Fig. 27-3) occur by separation

of cells and are lined with epithelium cells (as in

traumatic resin canals of softwoods); they often

occur in a single tangential row. The lysigenous

Fig. 27-3. Traumatic resin canals from Prunus

serotina filled with a gmnmy mass.

586 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

type occur by lysis (dissolution) of cells and are

not lined with epithelium cells.

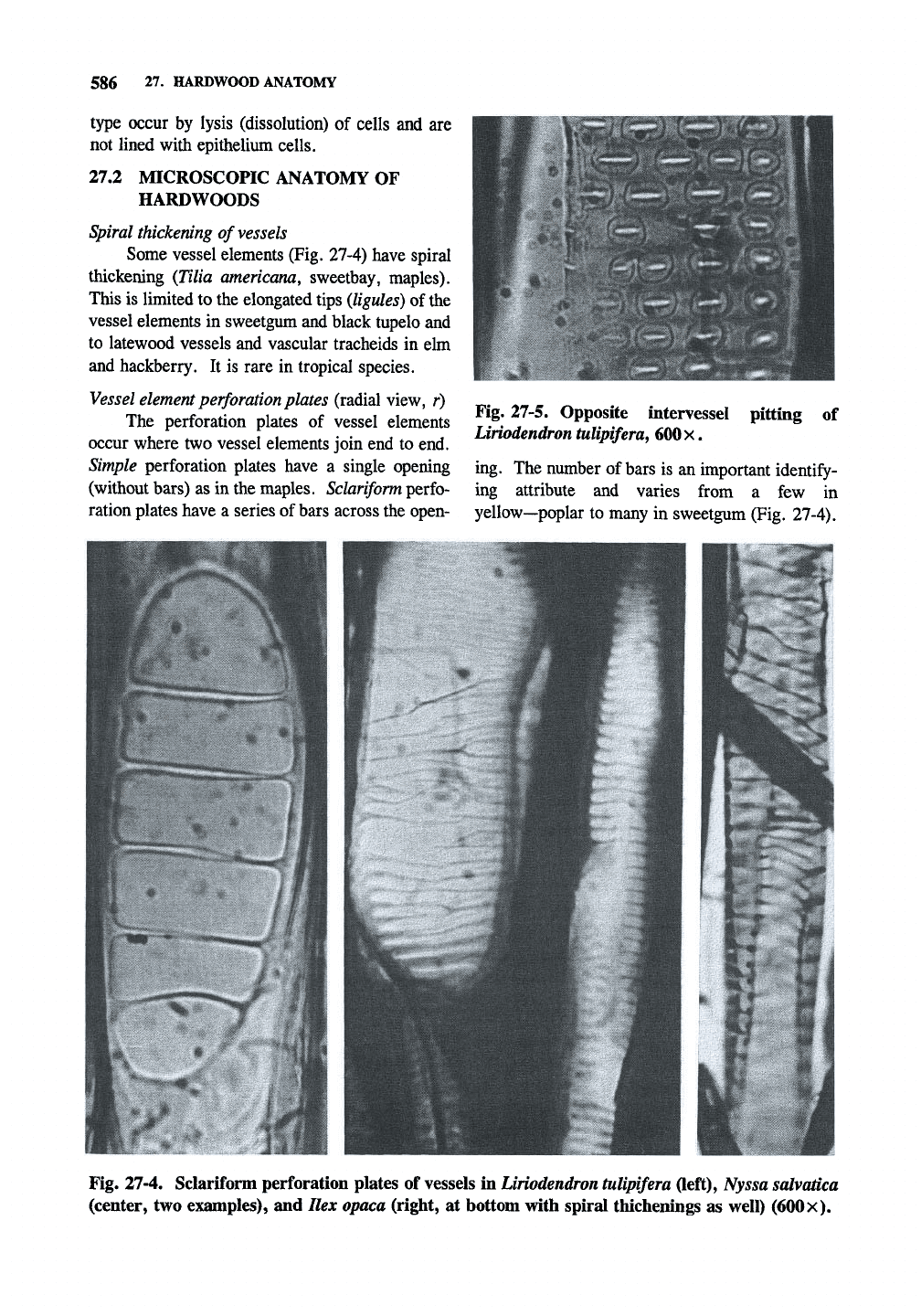

27.2 MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF

HARDWOODS

Spiral thickening of

vessels

Some vessel elements (Fig. 27-4) have spiral

thickening {Tilia americana, sweetbay, maples).

This is limited to the elongated tips

(ligules)

of the

vessel elements in sweetgum and black tupelo and

to latewood vessels and vascular tracheids in ehn

and hackberry. It is rare in tropical species.

Vessel element perforation plates (radial view, r)

The perforation plates of vessel elements

occur where two vessel elements join end to end.

Simple perforation plates have a single opening

(without bars) as in the maples.

Sclariform

perfo-

ration plates have a series of

bars

across the open-

Fig. 27-5. Opposite intervessel

Liriodendron

tuHpifera,

600

x.

pitting of

ing. The number of bars is an important identify-

ing attribute and varies from a few in

yellow—poplar to many in sweetgum (Fig. 27-4).

Fig. 27-4. Sclariform perforation plates of vessels in

Liriodendron

tulipifera Oeft), Nyssa salvatica

(center, two examples), and Ilex opaca (right, at bottom with spiral thichenings as well)

(600

x).

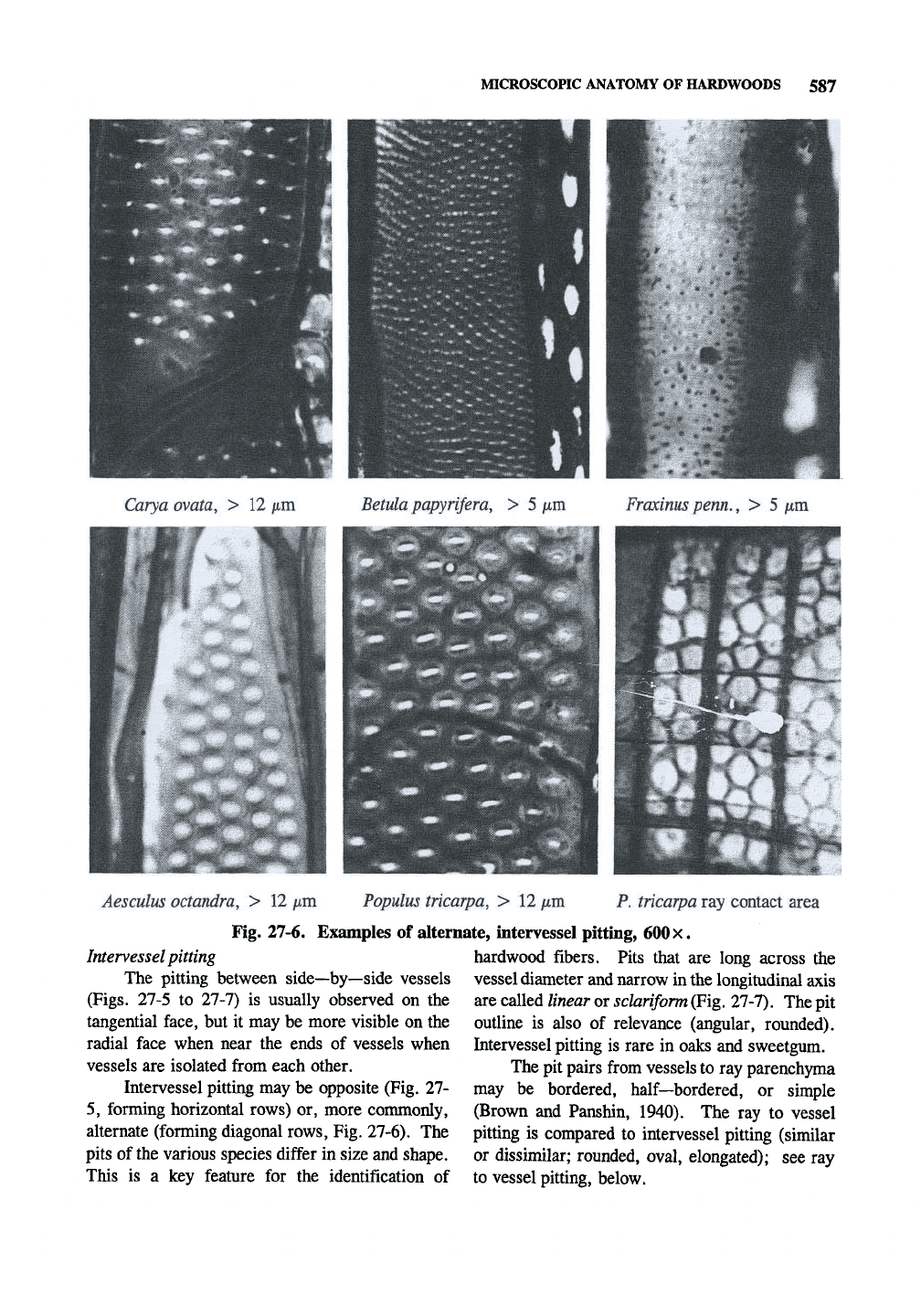

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF HARDWOODS 587

Carya ovata, > 12 ptm

Betula

papyrifera, > 5 ptm

Fraxinuspenn., > 5 fim

Aesculus octandra, > 12 iim Populus tricarpa, > 12 /im P. tricarpa ray contact area

Fig. 27-6. Examples of alternate, intervessel pitting, 600 x.

Intervessel pitting

The pitting between side—by—side vessels

(Figs.

27-5 to 27-7) is usually observed on the

tangential face, but it may be more visible on the

radial face when near the ends of vessels when

vessels are isolated from each other.

Intervessel pitting may be opposite (Fig. 27-

5,

forming horizontal rows) or, more commonly,

alternate (forming diagonal rows. Fig. 27-6). The

pits of the various species differ in size and shape.

This is a key feature for the identification of

hardwood fibers. Pits that are long across the

vessel diameter and narrow in the longitudinal axis

are called linear or

sclariform

(Fig.

27-7). The pit

outline is also of relevance (angular, rounded).

Intervessel pitting is rare in oaks and sweetgum.

The pit pairs from vessels to ray parenchyma

may be bordered, half—bordered, or simple

(Brown and Panshin, 1940). The ray to vessel

pitting is compared to intervessel pitting (similar

or dissimilar; rounded, oval, elongated); see ray

to vessel pitting, below.

588

27.

HARDWOOD ANATOMY

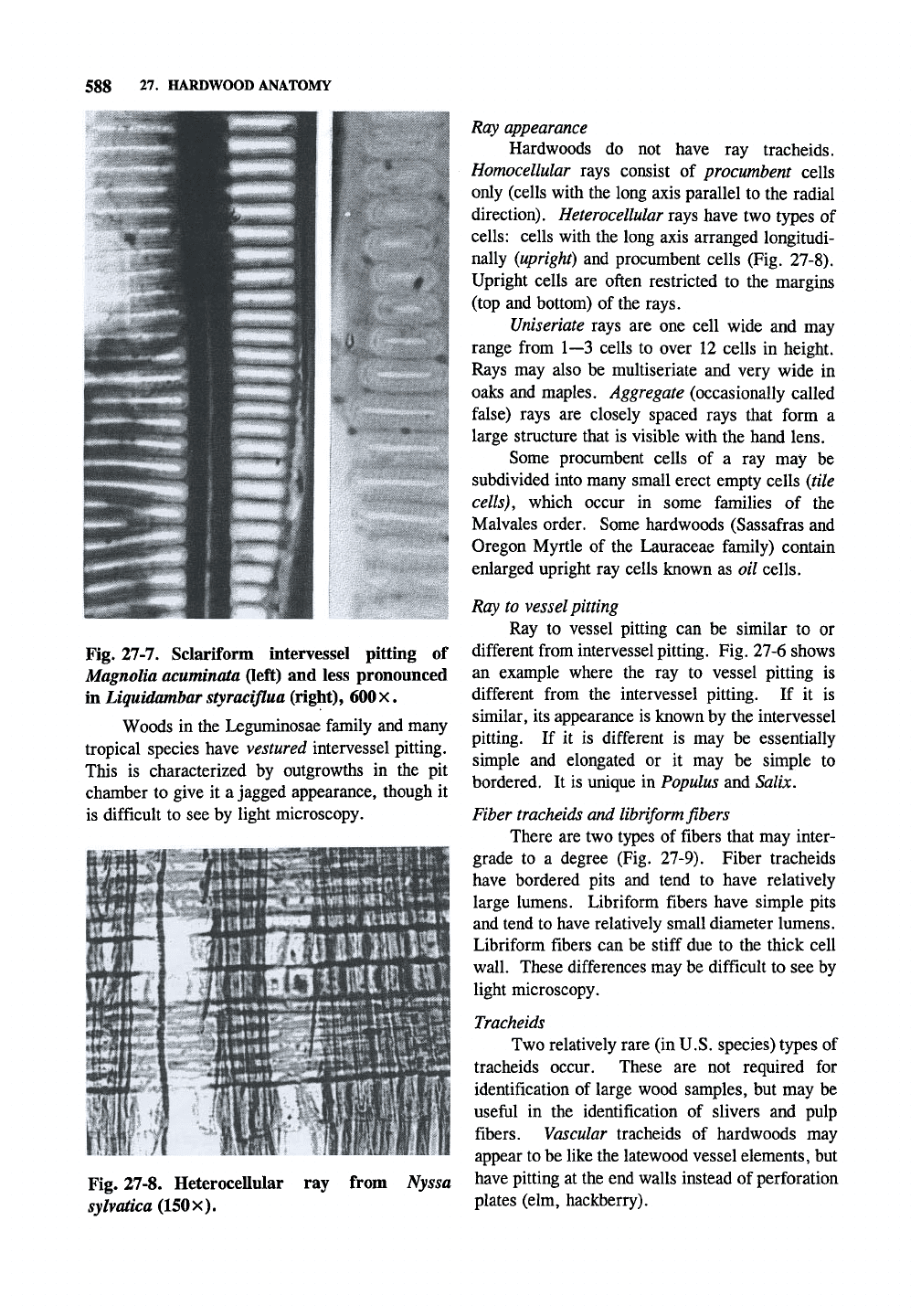

Fig. 27-7. Sclariform intervessel pitting of

Magnolia acuminata (left) and less pronounced

in Liquidambar styraciflua (right), 600 x.

Woods in the Leguminosae family and many

tropical species have vestured intervessel pitting.

This is characterized by outgrowths in the pit

chamber to give it a jagged appearance, though it

is difficult to see by light microscopy.

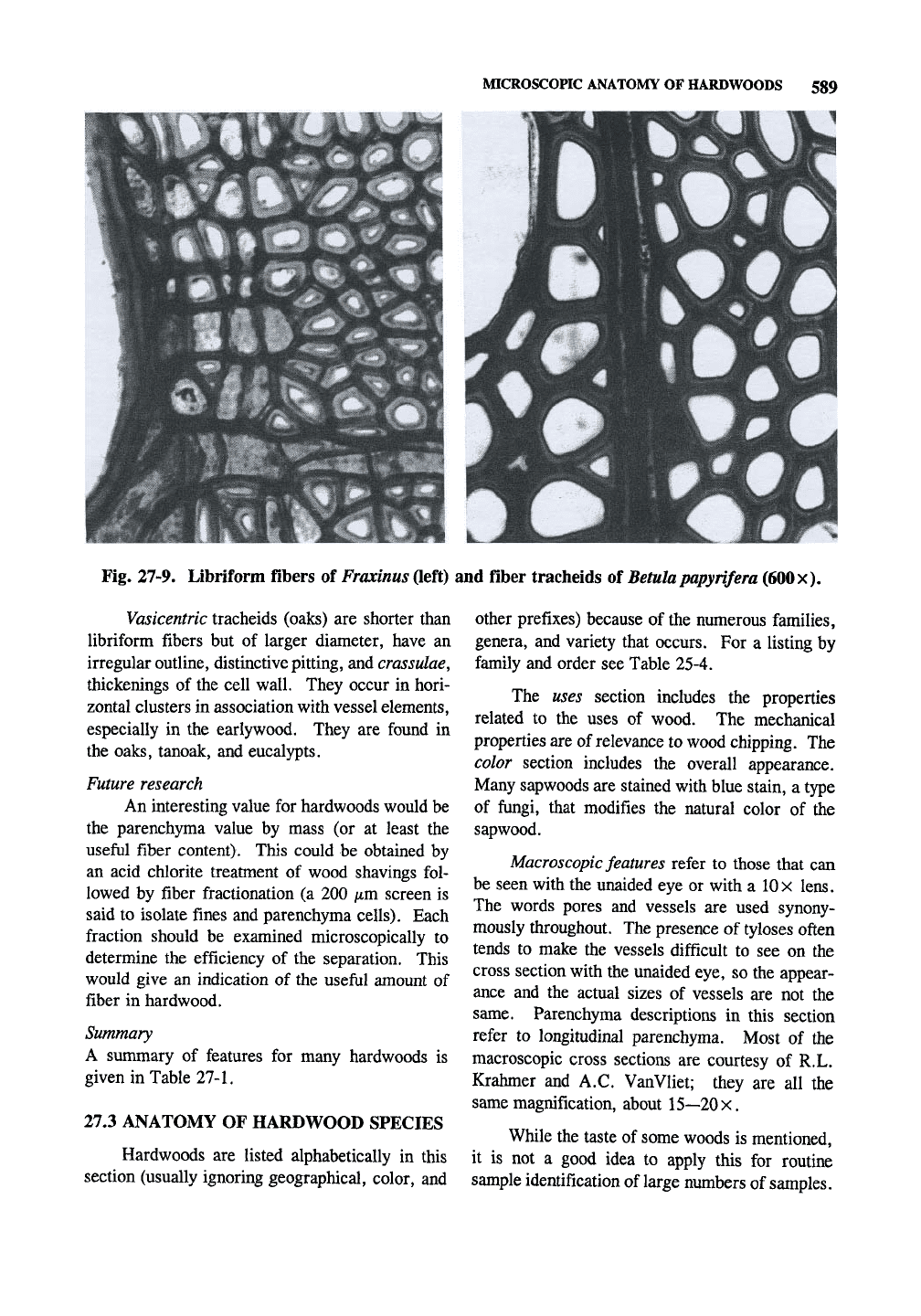

Fig. 27-8. Heterocellular

sylvatica

(150

x).

ray from Nyssa

Ray appearance

Hardwoods do not have ray tracheids.

Homocellular rays consist of procumbent cells

only (cells with the long axis parallel to the radial

direction). Heterocellular rays have two types of

cells:

cells with the long axis arranged longitudi-

nally {upright) and procumbent cells (Fig. 27-8).

Upright cells are often restricted to the margins

(top and bottom) of the rays.

Uniseriate rays are one cell wide and may

range from 1—3 cells to over 12 cells in height.

Rays may also be multiseriate and very wide in

oaks and maples. Aggregate (occasionally called

false) rays are closely spaced rays that form a

large structure that is visible with the hand lens.

Some procumbent cells of a ray may be

subdivided into many small erect empty cells (tile

cells),

which occur in some families of the

Malvales order. Some hardwoods (Sassafras and

Oregon Myrtle of the Lauraceae family) contain

enlarged upright ray cells known as oil cells.

Ray to vessel pitting

Ray to vessel pitting can be similar to or

different from intervessel pitting. Fig. 27-6 shows

an example where the ray to vessel pitting is

different from the intervessel pitting. If it is

similar, its appearance is known by the intervessel

pitting. If it is different is may be essentially

simple and elongated or it may be simple to

bordered. It is unique in Populus and Salix.

Fiber

tracheids

and libriform fibers

There are two types of fibers that may inter-

grade to a degree (Fig. 27-9). Fiber tracheids

have bordered pits and tend to have relatively

large lumens. Libriform fibers have simple pits

and tend to have relatively small diameter lumens.

Libriform fibers can be stiff due to the thick cell

wall. These differences may be difficult to see by

light microscopy.

Tracheids

Two relatively rare (in

U.S.

species) types of

tracheids occur. These are not required for

identification of large wood samples, but may be

useful in the identification of slivers and pulp

fibers.

Vascular tracheids of hardwoods may

appear to be like the latewood vessel elements, but

have pitting at the end walls instead of perforation

plates (elm, hackberry).

MICROSCOPIC ANATOMY OF HARDWOODS

589

1

r

^1^$

Fig. 27-9. Libriform fibers of

Fraxinus

(left) and fiber tracheids of

Betula

papyrifera

(600

x).

Vasicentric tracheids (oaks) are shorter than

libriform fibers but of larger diameter, have an

irregular outline, distinctive pitting, and crassulae,

thickenings of the cell wall. They occur in hori-

zontal clusters in association with vessel elements,

especially in the earlywood. They are found in

the oaks, tanoak, and eucalypts.

Future research

An interesting value for hardwoods would be

the parenchyma value by mass (or at least the

useful fiber content). This could be obtained by

an acid chlorite treatment of wood shavings fol-

lowed by fiber fractionation (a 200 jum screen is

said to isolate fines and parenchyma cells). Each

fraction should be examined microscopically to

determine the efficiency of the separation. This

would give an indication of the useful amount of

fiber in hardwood.

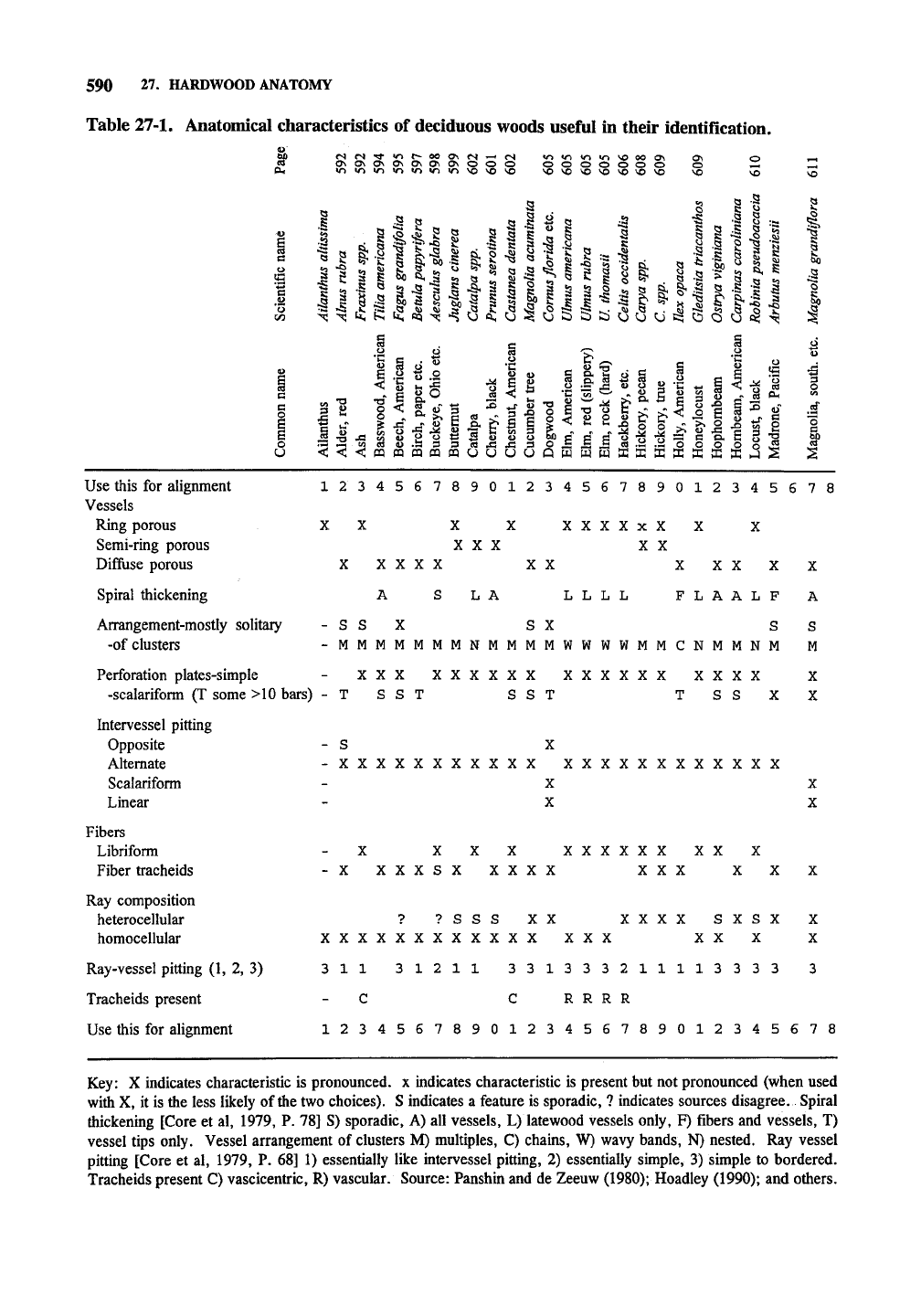

Summary

A sunmiary of features for many hardwoods is

given in Table 27-1.

27.3 ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECIES

Hardwoods are listed alphabetically in this

section (usually ignoring geographical, color, and

other prefixes) because of the numerous families,

genera, and variety that occurs. For a listing by

family and order see Table 25-4.

The uses section includes the properties

related to the uses of wood. The mechanical

properties are of relevance to wood chipping. The

color section includes the overall appearance.

Many sapwoods are stained with blue stain, a type

of fungi, that modifies the natural color of the

sapwood.

Macroscopic features refer to those that can

be seen with the unaided eye or with a lOx lens.

The words pores and vessels are used synony-

mously throughout. The presence of tyloses often

tends to make the vessels difficult to see on the

cross section with the unaided eye, so the appear-

ance and the actual sizes of vessels are not the

same. Parenchyma descriptions in this section

refer to longitudinal parenchyma. Most of the

macroscopic cross sections are courtesy of R.L.

Krahmer and A.C. VanVliet; they are all the

same magnification, about 15—20x.

While the taste of some woods is mentioned,

it is not a good idea to apply this for routine

sample identificafion of large numbers of samples.

590

27.

HARDWOOD ANATOMY

Table 27-1. Anatomical characteristics of deciduous woods useful in their identification.

0^0^0^0^0^0^0^000

§:.§

i I

•S

^

II

II

3 Q

OQ ^ S

S "^

«n

m

»r> ir> vo oo o>

o o o o o o o

so vo vo vo vo vo vo

3

•a D

;5

I

S3

<^

c3<i;c3:|

<3S

I

II

=55 O

I

Is

•S

?

.Bb

^

S

S

I I

ft- ^

O

i

O

o

U

< < <

ti -^ *^ ^

o

S3

0) U U ^

ij '^ s: o o g

I ^ ^

?^

^ ^

< 1

2 3 «

< ^ e

- >% o

SCO,

' o o

X X

2i

o

a

Use this for alignment

Vessels

Ring porous

Semi-ring porous

Diffuse porous

Spiral thickening

Arrangement-mostly solitary

-of clusters

Perforation plates-simple

1234567890123456789012345678

XX X X XXXXxXX X

XXX XX

XXXXX XX XXXXX

L A

L L L L

F L A A L F

-SSX SX SS

-MMMMMMMNMMMMWWWWMMCNMMNM M

XXX XXXXXX XXXXXX XXXX

-scalariform (T some >10 bars) - T S S T

S S T

S

S

Intervessel pitting

Opposite

Alternate

Scalariform

Linear

Fibers

Libriform

Fiber tracheids

Ray composition

heterocellular

homocellular

Ray-vessel pitting (1, 2, 3)

Tracheids present

Use this for alignment

- S X

-xxxxxxxxxxx xxxxxxxxxxxx

X

X

X X X X XXXXXX XX X

-X XXXSX XXXX XXX X X

? ?SSS XX XXXX SXSX

xxxxxxxxxxxx XXX XX X

X

X

X

X

X

X

311 31211 331333211113333 3

C C R R R R

1234567890123456789012345678

Key: X indicates characteristic is pronounced, x indicates characteristic is present but not pronounced (when used

with X, it is the less likely of

the

two choices). S indicates a feature is sporadic, ? indicates sources disagree. Spiral

thickening [Core et al, 1979, P. 78] S) sporadic. A) all vessels, L) latewood vessels only, F) fibers and vessels, T)

vessel tips only. Vessel arrangement of clusters M) multiples, C) chains, W) wavy bands, N) nested. Ray vessel

pitting [Core et al, 1979, P. 68] 1) essentially like intervessel pitting, 2) essentially simple, 3) simple to bordered.

Tracheids present C) vascicentric, R) vascular. Source: Panshin and de Zeeuw (1980); Hoadley (1990); and others.

ANATOMY

OF HARDWOOD

SPECIES 591

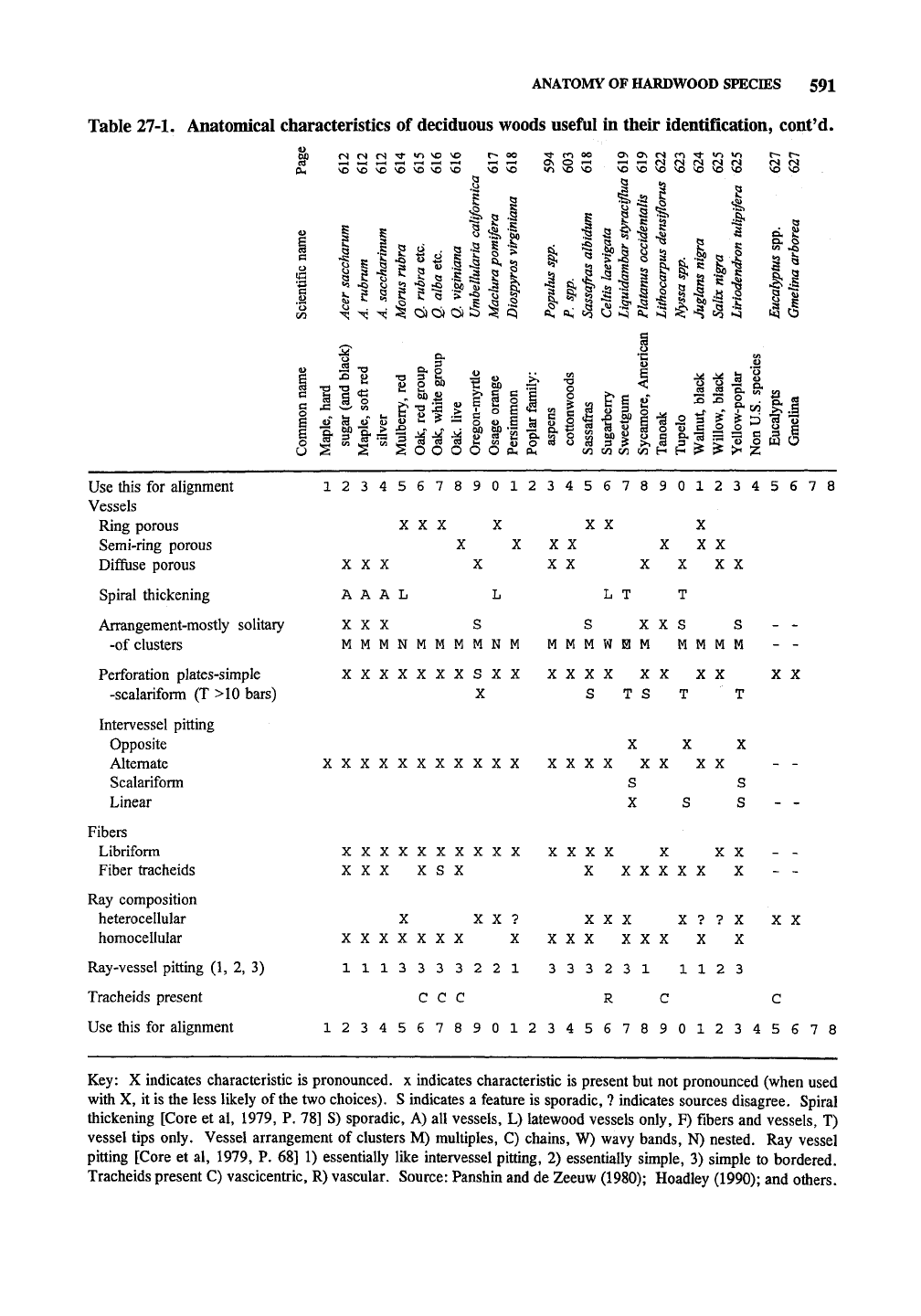

Table 27-1. Anatomical characteristics of deciduous woods useful in their identification, cont'd.

LI

.III i ,

9.§

o

2

I

:-i:-

6IIIII

° 11

i

111 !>

I

i^

o ^

I rs f I

i|f|l|§ll||llllilill||il|l^

Use this for alignment 1234567890123456789012345678

Vessels

Ring porous XXX X XX X

Semi-ring porous X XXX XXX

Diffiise porous XXX X XX XXXX

Spiral thickening AAAL L LT T

Arrangement-mostly solitary XXX S S XXS S--

-of clusters MMMNMMMMNM MMMWHM MMMM --

Perforation plates-simple XXXXXXXSXX XXXX XX XX XX

-scalariform (T >10 bars) X S T S T T

Intervessel pitting

Opposite XXX

Alternate XXXXXXXXXXX XXXX XX XX --

Scalariform S S

Linear X S S - -

Fibers

Libriform XXXXXXXXXX XXXX X XX --

Fiber tracheids XXX XSX X XXXXX X --

Ray composition

heterocellular X XX? XXX X??XXX

homocellular XXXXXXX X XXX XXX X X

Ray-vessel pitting (1, 2, 3) 1113333221 333231 1123

Tracheids present C C C R C C

Use this for alignment 1234567890123456789012345678

Key: X indicates characteristic is pronounced, x indicates characteristic is present but not pronounced (when used

with X, it is the less likely of the two choices). S indicates a feature is sporadic, ? indicates sources disagree. Spiral

thickening [Core et al, 1979, P. 78] S) sporadic. A) all vessels, L) latewood vessels only, F) fibers and vessels, T)

vessel tips only. Vessel arrangement of clusters M) multiples, C) chains, W) wavy bands, N) nested. Ray vessel

pitting [Core et al, 1979, P. 68] 1) essentially like intervessel pitting, 2) essentially simple, 3) simple to bordered.

Tracheids present C) vascicentric, R) vascular. Source: Panshin and de Zeeuw (1980); Hoadley (1990); and others.

592 27. HARDWOOD ANATOMY

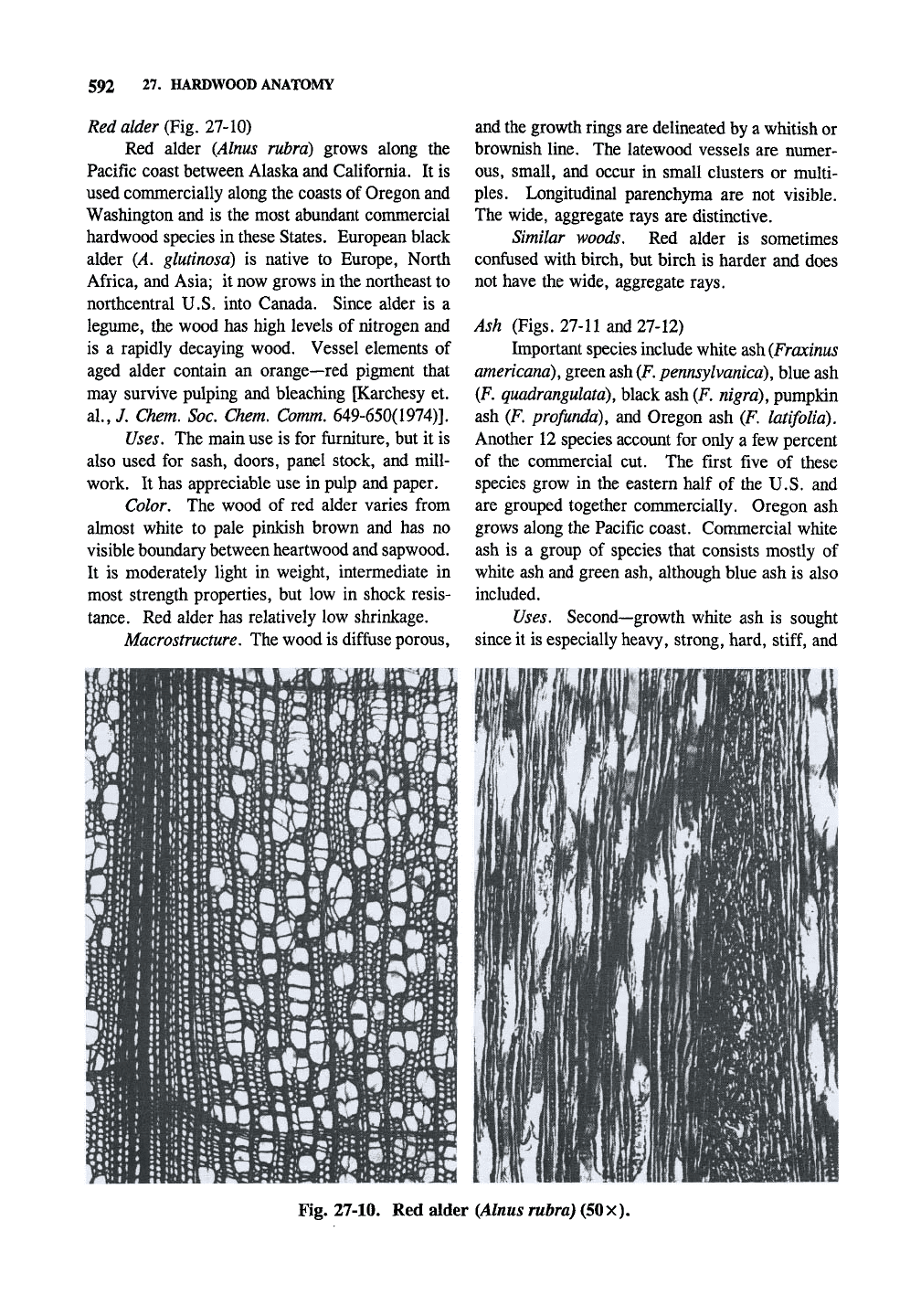

Red alder (Fig. 27-10)

Red alder (Alnus rubra) grows along the

Pacific coast between Alaska and California. It is

used commercially along the coasts of Oregon and

Washington and is the most abundant commercial

hardwood species in these States. European black

alder (A. glutinosa) is native to Europe, North

Africa, and Asia; it now grows in the northeast to

northcentral U.S. into Canada. Since alder is a

legume, the wood has high levels of nitrogen and

is a rapidly decaying wood. Vessel elements of

aged alder contain an orange—red pigment that

may survive pulping and bleaching [Karchesy et.

al.,

7. Chem. Soc. Chem. Comm. 649-650(1974)].

Uses, The main use is for furniture, but it is

also used for sash, doors, panel stock, and mill-

work. It has appreciable use in pulp and paper.

Color, The wood of red alder varies from

almost white to pale pinkish brown and has no

visible boundary between heartwood and sapwood.

It is moderately light in weight, intermediate in

most strength properties, but low in shock resis-

tance. Red alder has relatively low shrinkage.

Macrostructure, The wood is diffuse porous.

and the growth rings are delineated by a whitish or

brownish line. The latewood vessels are numer-

ous,

small, and occur in small clusters or multi-

ples.

Longitudinal parenchyma are not visible.

The wide, aggregate rays are distinctive.

Similar woods. Red alder is sometimes

confused with birch, but birch is harder and does

not have the wide, aggregate rays.

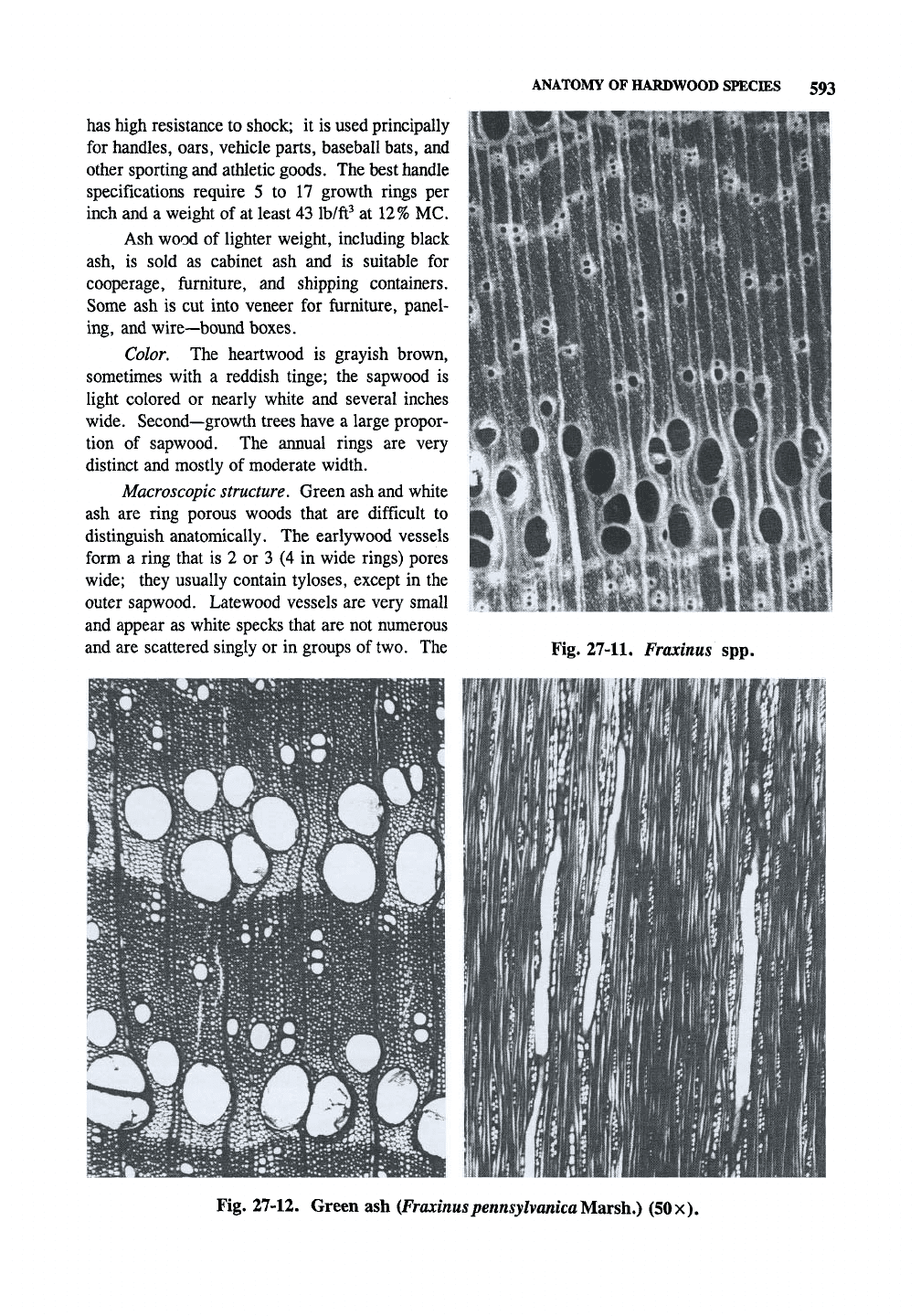

Ash (Figs. 27-11 and 27-12)

Important species include white ash

(Fraxinus

americana), green ash

(F.

pemsylvanica), blue ash

(F.

quadrangulata),

black ash

(F.

nigra), pumpkin

ash (F. profunda), and Oregon ash (F. latifolia).

Another 12 species account for only a few percent

of the commercial cut. The first five of these

species grow in the eastern half of the U.S. and

are grouped together commercially. Oregon ash

grows along the Pacific coast. Commercial white

ash is a group of species that consists mostly of

white ash and green ash, although blue ash is also

included.

Uses. Second—growth white ash is sought

since it is especially heavy, strong, hard,

stiff,

and

Fig. 27-10. Red alder

{Alnus

rubra) (50x).

ANATOMY OF HARDWOOD SPECffiS 593

has high resistance to shock; it is used principally

for handles, oars, vehicle parts, baseball bats, and

other sporting and athletic goods. The best handle

specifications require 5 to 17 growth rings per

inch and a weight of at least 43 Ib/ft^ at 12% MC.

Ash wood of lighter weight, including black

ash, is sold as cabinet ash and is suitable for

cooperage, furniture, and shipping containers.

Some ash is cut into veneer for furniture, panel-

ing, and wire—bound boxes.

Color. The heartwood is grayish brown,

sometimes with a reddish tinge; the sapwood is

light colored or nearly white and several inches

wide. Second—growth trees have a large propor-

tion of sapwood. The annual rings are very

distinct and mostly of moderate width.

Macroscopic structure. Green ash and white

ash are ring porous woods that are difficult to

distinguish anatomically. The early wood vessels

form a ring that is 2 or 3 (4 in wide rings) pores

wide; they usually contain tyloses, except in the

outer sapwood. Latewood vessels are very small

and appear as white specks that are not numerous

and are scattered singly or in groups of

two.

The

• ilni I-n

^

i

Fig.

27-11.

Fraxinus spp.

Fig. 27-12. Green ash

(FraxinuspennsylvanicaMsLrsh.)

(50x).