Beglar D., Murray N. Inside Track to Writing Dissertations and Theses

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

4 Clear and effective writing

106

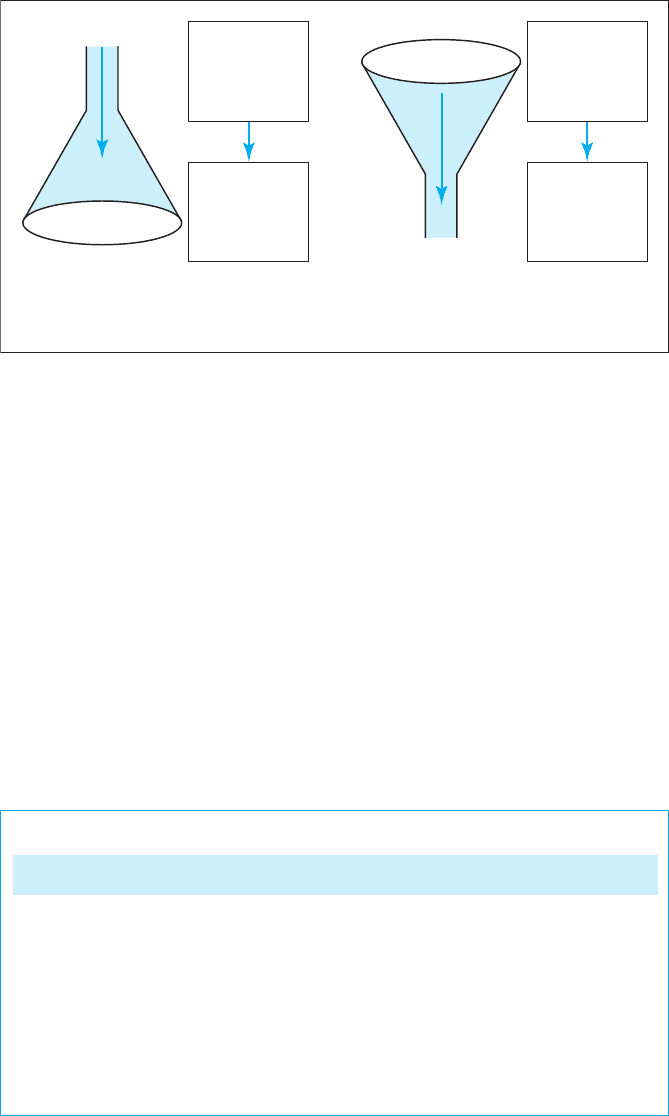

The difference between these two approaches can be represented in terms of a fun-

nel (see Figure 4.1). When the thesis statement appears at the beginning of the intro-

duction, there is a move from specific (the statement itself) to more general (the

contextual backdrop); when it appears at the end, there is a move from general

(the contextual backdrop) to more specific (the thesis statement).

In the case of the second option, if your introduction has been well constructed you

should begin with the more general information and gradually narrow your focus in

such a way that the reader may well be able to predict the thesis statement. In other

words, your thesis statement should naturally emerge or ‘drop out of’ the contextual

discussion that precedes it.

Look at these two examples, one of which places the thesis statement at the begin-

ning of the introduction, and the other which places it at the end.

General

(background

information/

context)

General

(background

information/

context)

Specific

(thesis

statement)

Thesis statement placed at

beginning of introduction

Thesis statement placed at

end of introduction

Specific

(thesis

statement)

Figure 4.1 Positioning of the thesis statement

Example 1: at the beginning

This study critically evaluates that body of evidence frequently cited in support

of the idea that the prolonged use of mobile phones is harmful to health.

Ever since analogue mobile phones appeared in the 1980s, there has been a

debate over the health risks associated with their use. Some claim that the radio-

frequency radiation that handsets emit enters the head injuring living tissue

and possibly triggering a brain tumour or other disease. However, while

their use does appear to produce changes in brain temperature and activity

as well as blood pressure changes, many dispute findings as inconsistent

and unreliable.

Given that nearly 2 billion people use a mobile phone, the question over

their safety is an important one. It is also divisive. Just as there is no agreement

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 106

107

The style of academic writing

within the academic research community, so too there is none among the wider

population many of whom express scepticism and mistrust over the claims of

researchers and mobile phone manufacturers respectively. What many call for,

however, is an honest presentation of the facts and an objective evaluation

of the evidence presented to date.

Example 2: at the end

Both in the United Kingdom and elsewhere (Australia and the United States),

enabling education today occupies an increasingly prominent place on social,

political and educational agendas, driven as it is by notions of a better edu-

cated, more fulfilled society, and a more competent and productive workforce

that is able to respond to the changing needs of a dynamic labour market.

University foundation programmes constitute one important vehicle

through which to provide those individuals who, for a variety of reasons (eco-

nomic, family, health, etc.) were unable or disinclined to pursue their education

at an earlier stage in their careers, with the opportunity to develop themselves

through the completion of a course of study designed to prepare them for life

as undergraduates and ultimately as fulfilled members of society.

In establishing these programmes, universities are seen as being responsive

to the current climate of social justice and opportunity for all. However, their

increasing popularity has meant a substantial investment of human and finan-

cial resources on the understanding that they do indeed benefit the individual

and society at large. With this in mind, this paper investigates the perceived

and actual benefits of such programmes from the points of view of students in

pre-tertiary enabling education, and the academic staff who encounter them

in subsequent undergraduate courses.

Write the introduction to a chapter on the causes of teenage depression. Using the

information listed below as a series of bullet points, write two versions of the intro-

duction, one with the thesis statement at the beginning and the other with it at the

end. Feel free to rearrange the information or to add additional information, if you

wish, but try to keep the introduction brief.

■ Research shows that in the past 10 years the incidence of teenage depression

has increased markedly.

■ Counsellors, GPs, psychiatrists and psychologists are seeing a general increase

in the proportion of young people requiring treatment for the disorder.

■ Teenage depression is far more of an issue in the developed world.

■ Teenage girls are more susceptible to depression than teenage boys.

■ Depression in children can take an enormous psychological toll on the parents

of those who suffer.

Activity 4.7 Constructing and positioning thesis statements

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 107

4 Clear and effective writing

108

Explicit vs implicit thesis statements

Another decision you may want to make about your thesis statement is whether to

make it an explicit or implicit statement. Explicit thesis statements state directly

what issue the upcoming discussion will address. Both thesis statements in the two

examples above do this:

. . . this paper investigates the perceived and actual benefits of such programmes

from the points of view of students in pre-tertiary enabling education, and the

academic staff who encounter them in subsequent undergraduate courses.

This paper critically evaluates that body of evidence frequently cited in support

of the idea that the prolonged use of mobile phones is harmful to health.

In contrast, implicit thesis statements state indirectly the issue that will be

addressed in the upcoming discussion. In other words, the reader is left to infer

what the main focus of that discussion will be. Look at the example below in which

Example 1 above has been rewritten using an implicit thesis statement.

In establishing these programmes, universities are seen as being responsive

to the current climate of social justice and opportunity for all. However,

their increasing popularity and the substantial investment of human and

financial resources that they represent begs the question of what the perceived

and actual benefits of such programmes are from the points of view of students

in pre-tertiary enabling education, and the academic staff who encounter them

in subsequent undergraduate courses.

Here’s another example of an implicit thesis statement that appeared at the end of

an introduction to a piece of writing that discussed the ways in which schools and

parents need to co-operate in the moral education of children.

If children are to feel secure in this way and acquire a clear, unambiguous

sense of right and wrong, it is imperative that they not receive mixed messages

about what is and is not acceptable behaviour. Consistency and reinforcement

are everything and as such there is a series of measures currently under

discussion which seeks to ensure an ongoing dialogue between schools and

parents and revolving around children’s moral education.

If the introduction has been carefully constructed, an implicit thesis statement –

despite being indirect – should leave the reader in little or no doubt what the main

focus is of the subsequent discussion. However, for it to work, there will normally

need to be enough contextual or ‘lead-up’ information preceding it (see the right-

hand funnel in Figure 4.1). This means that implicit thesis statements almost always

occur at or toward the end of an introduction.

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 108

109

The style of academic writing

As a rule, however, we suggest that you avoid the use of questions as thesis state-

ments in a dissertation or thesis. While they may occasionally be used discriminat-

ingly in a chapter introduction, they should certainly not be used in the main

introduction to the work (

➨

see Chapter 5, p. 146).

In establishing these programmes, universities are seen as being responsive to

the current climate of social justice and opportunity for all. However, their

increasing popularity has meant a substantial investment of human and finan-

cial resources. What then, it might reasonably be asked, are the perceived and

actual benefits of such programmes from the points of view of students in pre-

tertiary enabling education, and the academic staff who encounter them in

subsequent undergraduate courses?

Look again at the introduction you created in Activity 4.6, earlier in this section.

Think of two implicit thesis statements either of which could replace the original the-

sis statement you constructed for that exercise and which appeared at the end of

the introduction. Write your two implicit thesis statements below:

1

2

Activity 4.8 Writing an introduction 2

Introductions: useful expressions

This chapter/section/article seeks to address (the question of) . . .

In the pages that follow, . . .

This chapter/section/article will look at/consider/present/discuss/assess/

evaluate . . .

This chapter will argue that . . .

In this section/chapter, evidence will be presented in support of the idea that . . .

This raises the question of whether and to what extent . . .

Occasionally a question might serve as an implicit thesis statement, as in the follow-

ing example:

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/16/09 11:18 AM Page 109

4 Clear and effective writing

110

Providing an overview

Another way to build reader interest is to give them an overview of what is to come

in your discussion. This (hopefully) not only motivates them to read on, but also

serves as a navigational tool that helps orientate them as they read through your

work. Knowing in advance in what direction a discussion is going can be reassuring

for a reader, not least because it can help them better understand and appreciate

the significance of what they are reading at any particular point.

One common student misconception is that an introduction should consist of one

paragraph. Not so! It can consist of any number of paragraphs. The rule for begin-

ning a new paragraph applies in introductions in exactly the same way as it does

elsewhere in your writing: whenever you begin a new idea with its own clearly-

identifiable topic sentence, start a new paragraph. An introduction may well contain

a number of such ideas and will therefore warrant a series of paragraphs. The same

is true of conclusions, discussed below.

Look at the ideas you listed in Activity 4.6, earlier in this section. On a separate piece

of paper, write a short introduction to a chapter designed to focus on the importance

of intercultural communication skills in the workplace.

Think carefully about these things:

■ how you will engage your reader

■ where you are going to put your thesis statement

■ how you are going to organise the information to create a good flow

■ how you will indicate the structure/direction of the chapter.

Activity 4.9 Writing an introduction 3

Summarising and concluding individual chapters

Conclusions, like introductions, can often present students with difficulties. Just as

they find it difficult to open up their discussion, they also tend to have problems

‘rounding it off’ in such a way that it comes to a natural close.

One of the main weaknesses with students’ conclusions is that, frequently, they actually

conclude nothing but merely repeat what they’ve already said. In other words, they

summarise and in doing so appear to consider summaries and conclusions to be one

and the same thing. They are not! Let’s look at each in turn, starting with summaries.

Summaries

Summarising means taking information you’ve already discussed and restating it

in a more condensed form. Sometimes it may be in the form of full prose, at others

it may consist of a series of bullet points. The contents of a 15-page dissertation

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 110

111

The style of academic writing

chapter, for example, might be reduced down to two-thirds of a page or a series

of eight bullet points. The main purpose of summarising is to give the reader an at-

a-glance overview of the main points of a chapter (or part of a chapter), and this

in turn has a number of benefits:

■ It helps the reader see the wood from the trees. Particularly if a chapter or journal

article is long, complex and information-rich, the reader can become disorien-

tated and lose their sense of its structure, how the various sections and sub-

sections relate to each other, and where exactly they, the reader, are currently

located in the chapter. This can happen despite the fact that the introduction may

have mapped out the direction of the article or chapter.

■ It serves as a reminder of the main points discussed.

■ It can help link what has been discussed to what is about to be discussed. In

other words, it can help smooth the transition between two consecutive parts of

a chapter or article, or between two chapters.

Although they are often encouraged, particularly within the context of dissertations

and theses where chapters tend to be long and complex, whether or not to include

a summary is very much down to the judgement of the individual writer/researcher.

Once again, accessibility and comprehensibility must be paramount and each writer

has to put themselves in their reader’s shoes and ask whether, in the absence of a

summary, their work remains clear and easy to process. Conversely, they may wish

to ask themselves, ‘Would a summary make the reader’s life easier here?’

If it is considered necessary, a summary will often form the initial part of a conclu-

sion but it does not need to. It may stand alone as a ‘Summary’ or be incorporated

within the main text of the body of the chapter or article. There may, in fact, be a

number of short summaries within a single chapter, particularly if it’s a long and

complex chapter with a number of foci. The summary may be presented as a series

of bullet points or as normal prose.

Summaries: useful expressions

This chapter/section has discussed the following: . . .

This chapter/section has sought to . . .

This chapter/section has . . .

This chapter has looked at/addressed a number of ...First, . . .

The key points discussed so far are: . . .

Five main ideas have been critically appraised in this chapter. To begin with . . .

In summary, . . .

To summarise, . . .

The main points discussed in this chapter can be summarised as follows: . . .

In summary, the argument/position is as follows: . . .

We might summarise the main points thus: . . .

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 111

4 Clear and effective writing

112

Now look at the examples of chapter summaries.

Examples of chapter summaries

This chapter has examined communication strategies used by second language

learners (and native speakers) when they are faced with a production problem.

They consist of substitute plans and are potentially conscious.A typology of com-

munication strategies distinguishes reduction strategies, which are used to avoid

the problem altogether, and achievement strategies, which are used to overcome

the problem.The latter can be further subdivided into compensatory strategies

(including both first language and second language based strategies) and

retrieval strategies. There has been only limited empirical study of communi-

cation strategies, but there is evidence to suggest that their use is influenced by

the learner’s proficiency level, the nature of the problem-source, the learner’s

personality, and the learning situation. It is not yet clear what effect, if any,

communicative strategies have on linguistic development.

(Adapted from Ellis, 1985: 188)

This chapter has sought to show that since the 1990s there has been more tele-

vision news produced for the UK audience than ever before, and that despite

the concerns of some within the industry, the traditional public service commit-

ment to high-quality news remains written into the broadcasting legislation.

Furthermore, the statistics suggest that commercial television is similarly com-

mitted to quality journalism at peak-time. News, it seems, is popular and there-

fore justifiable on purely commercial grounds. The prospects for current affairs

broadcasting, particularly on Channel 3, are less certain because financial

pressures may lead to cuts in the number of programmes broadcast as well as

changes to scheduling.

(Adapted from McNair, 1994: 121–2)

Look at the text below. Although it’s considerably shorter than a chapter in a disser-

tation or thesis, write a summary of the information it contains using the guidelines

above.

Activity 4.10 Summarising a text

Both Burma and Iran are repressive authoritarian regimes: the former a mili-

tary regime, the latter a theocratic state. Of the two, Iran seems to exhibit a

greater tendency to totalitarianism, although in an incomplete form. Neverthe-

less, the near total control of all levers of power by Iran’s conservative clergy

since 2005 indicates that there may be further movement in this direction

(Linz, 2000: 36; Kaboli, 2006b). Regardless of definitional debates about regime

types there can be no question that the opportunities for genuine green dissent

in these countries are severely constrained, but also constrained differently. In

Iran, green issues have been largely coopted by the state, with state-sanctioned

NGOs the dominant voice – dissenting groups exist, but with little public

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 112

113

The style of academic writing

Conclusions

A conclusion is a way to round off a discussion; it may be a discussion that has

taken place in an essay, a chapter of a book, thesis or dissertation, or the entire

work (

➨

see Chapter 5, p. 182). Either way, the purpose of a conclusion is always

the same: to draw together all strands of the discussion up to that point and provide

a resolution of some kind.

What is a ‘resolution’? It is a statement that may span a single paragraph, a series of

paragraphs or a whole document, and which will comment in general terms on

information presented in the foregoing discussion. It is statement, based on obser-

vation and reason, of what can be said in the light of that discussion, and as

such will offer new information or insights that emerge from it. This providing of new

information is a key characteristic of a conclusion and one that distinguishes it from

presence. In Burma, green issues are linked inextricably with human rights,

particularly those of ethnic minorities, and this nexus has led to the develop-

ment of the new discourse of earth rights. The only options for dissent here are

military insurgency or the voicing of grievances in international fora.

In Iran, the state-sanctioned green sector is encouraged by the regime as a

safe form of participation. Opposition is even more limited than in the 1990s

because many Iranians understandably fear foreign invasion or attacks. The

military forces of the United States are at both the Afghanistan and Iraqi bor-

ders with Iran, and concerns about foreign military action including nuclear

strikes are not without foundation (Hersh, 2006). Thus, the emergence of a

tightly controlled green politics in Iran may further perpetuate oligarchic

control by the theocracy, rather than being a harbinger of change, as it was in

Hungary (see Kerenyi and Szabo, this issue). Contrarily, the most exciting thing

about green politics in Iran is that it gives a voice for young women, a voice

sadly missing since 1979.

So the transnational messages of environmentalism emanating from the

West have managed to cross the borders of these two non-democratic regimes,

but not in a form recognisable as western environmentalism, as these state

boundaries are not mere speed bumps. Although limited in their power and

very different in character in each country there are green elements at work

that may provide the foundation for profound societal change in the future.

This is by no means guaranteed, however, and it may be that the prospects are

greatest in Burma, where environment and human rights have been linked

more strongly in struggles for survival. As the Burmese regime fights to

maximise its exploitation of energy supplies it is provoking a broader opposi-

tion. In Iran the coopted elements of the green movement may actually con-

tribute to sustaining authoritarian or totalitarian rule by offering a narrow,

post-materialist version of environmentalism, alongside a callow and tepid

version of civil society.

(Adapted from Doyle and Simpson, 2006: 763–4)

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 113

4 Clear and effective writing

114

the mere restatement of information that constitutes a summary. The information

itself and its significance can only be fully understood and appreciated within the

context of the foregoing discussion.

As we have seen, a summary can be a useful reminder of that foregoing discussion

and therefore help to ensure that the reader is able to see the relationship between

the ideas expressed in the body of the chapter or article, and those that the author

claims follow from them and that constitute the conclusion.

Below are some of the expressions commonly used to introduce conclusions.

Notice how they signal this necessarily close relationship between the preceding

discussion and the conclusion itself.

Conclusions: useful expressions

In conclusion, . . .

Together, this evidence suggests that . . .

From the foregoing discussion we can say that . . .

A number of things can be gleaned from this . . .

Based on these findings we can say that/it is apparent that . . .

To return to our original question, . . .

This chapter began with . . .

This chapter sought to/set out to . . .

Example: conclusion 1

This chapter has surveyed a number of methods and approaches to the teach-

ing of foreign languages, along with research that has sought to measure their

respective levels of efficacy. The picture that emerges is that learners have

learnt and continue to learn languages, often to the highest levels of profi-

ciency, having been taught by each of these methods and approaches. It seems,

therefore, that there may well be no such thing as the ‘ideal’ or ‘perfect’ method

or approach, and that there are other more important factors that determine

learners’ success in acquiring foreign languages.

Example: conclusion 2

As the preceding section makes clear, it is important to place great value on the

knowledge and experience of service users and to incorporate this into policy,

practice and education. The direct experience of service users does provide a

source of knowledge that has long been undervalued in social work, even

though the occupation has taken more steps in this direction than many others

(Beresford, 2000). However, social workers have to balance these against other

sources of knowledge that lie outside of the direct experience of service users,

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 114

115

The style of academic writing

as we have noted earlier. As the case studies have demonstrated, there are also

numerous practical difficulties that can complicate a social worker’s intention

to work alongside service users, acting as far as possible in accordance with

their wishes.

There is no single way if managing service user engagement, a message that

is made clear from a variety of different pieces of research. There will be nu-

merous sets of circumstances where the actions one takes as a social worker

will contradict an individual’s expressed desires, or will not balance the com-

peting preferences of users and carers, or when the evidence from other forms

of knowledge would strongly suggest a course of action that a service user does

not welcome. In such circumstances, the challenge will be to reach a solution

that respects the desires of each individual even if it does not equate with that

person’s wishes (Beresford et al., 2007).

(Adapted from Wilson et al., 2008: 428)

Example: conclusion 3

In terms of pronunciation, what the discussion in this chapter indicates is the

need for some sort of international core for phonological intelligibility: a set of

unifying features which, at the very least, has the potential to guarantee that

pronunciation will not impede successful communication in EIL [English as

an International Language] settings. This core will be contrived to the extent

that its features are not identical with those of any L1 or L2 variety of English.

As we will see in Chapter 6, a phonological core of this kind already exists

among all L1 speakers of English, whatever their variety. A core of sorts also

exists among L2 speakers, insofar as speakers of all languages share certain

phonological features and processes. However, this shared element is limited.

Thus, while we can build on what L2 speakers already have in common

phonologically, we must take the argument one very large step further by

identifying what they need to have in common and contriving a pedagogic

core that focuses on this need. However, such a core, while necessary, will not

alone be sufficient to achieve the goal of preventing pronunciation from

impeding communication. Mamgbose makes the obvious yet frequently

missed point that ‘it is people, not language codes, that understand one

another’ (1998: 11). Participants in EIL will also need to be able to tune into

each other’s accents and adjust both their own phonological output and their

respective expectations accordingly.

In Chapters 6 and 7 we will look more closely at these two approaches to EIL

communication and consider their pedagogic implications. Chapter 6 is both a

discussion of the complex issues involved in the establishing of a core of

phonological intelligibility for EIL, and a presentation of the core being pro-

posed here. Then, in Chapter 7, we move on to a consideration of how best

to both promote learners’ productive and receptive use of this core, and to

encourage the development of speaker/listener accommodative processes

which will facilitate mutual intelligibility in EIL. But first, in the following

chapter, we will consider in detail the relationship between L1 phonological

transfer and EIL intelligibility.

(Adapted from Jenkins, 2000: 95–6)

M04_BEGL1703_00_SE_C04.QXD 5/15/09 7:19 AM Page 115