Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

396 Freedom Riders

the southwestern Mississippi town where he worked as a crane operator for

the Illinois Central Railroad.

16

In mid-July, while Moses was in the process of moving to McComb, more

than a dozen SNCC leaders met in Baltimore to discuss the organization’s

progress and priorities, including the implications of the impending Pike County

project. During the three-day meeting, Charles Jones and other voting rights

enthusiasts associated with the “Belafonte Committee” took the initiative, calling

for the establishment of an extensive voting rights project headed by an execu-

tive director and staffed by at least eight full-time employees. Jones’s argu-

ment that the project should be SNCC’s “top priority” gained some support,

but a majority of those present opposed the project on either ideological or

practical grounds. Deferring a final decision on the voting rights proposal until

the next monthly meeting—scheduled for August 11–14 at the Highlander

Folk School, in Monteagle, Tennessee—the students asked Jones and the

Belafonte Committee to prepare a more precise description of the project’s

logistical and financial requirements.

17

During the four weeks between the Baltimore and Highlander meet-

ings, the SNCC leaders witnessed the anxious preparations for the Freedom

Rider trials and the growing apprehensions about the movement’s ability to

sustain direct action in the Deep South. To the dismay of the Justice Depart-

ment, however, their willingness to elevate voting rights over direct action as

an organizational priority remained very much in doubt. In late July and

early August a number of SNCC leaders—including Sherrod, Jones, Chuck

McDew, Diane Nash, John Lewis, Jim Bevel, and Stokely Carmichael—

participated in a student leadership seminar organized by voting rights en-

thusiast Tim Jenkins and funded by the New World Foundation. Held in

Nashville, the seminar focused on the problem of “Understanding the Na-

ture of Social Change” and featured presentations by the psychologist Ken-

neth Clark, the sociologist E. Franklin Frazier, the historian Rayford Logan,

and several other distinguished black scholars. John Doar of the Justice De-

partment and Herbert Hill of the NAACP were also on hand, adding to the

seminar’s orientation toward the institutional context of social change.

The seminar’s primary objective, according to Jenkins, was to give the

student leaders “a solid academic approach to understanding the movement.”

More specifically, he wanted to expand their appreciation for the institu-

tional “power of the Justice Department and its potential to help and protect

us in the political revolution.” As Jenkins later explained his motivation, in a

conversation with Carmichael: “Even before the Freedom Rides I didn’t think

we could allow the energy of the sit-ins simply to dissipate. After the rides, it

was even clearer that the student movement, if it were to survive at all, would

need a new, sustainable program and focus. And I certainly wanted to nudge

it down off that lofty, ethereal plane of ‘the beloved community’ and the

excessive zeal of the pain-and-suffering school of struggle. . . I felt what the

movement really needed at that point was not idealism or inspiration but

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 397

information. Hard, pragmatic information about how the political system

actually worked . . . or failed to work. Where the pressure points were. What

levers were available that students could push. Where allies might be found.

Who the real enemies were. What exactly was the nature of the beast we

were up against? That was the purpose in Nashville.” Thus, despite the pre-

tense of academic detachment, the prescribed necessity of deferring to the

federal government’s wishes hovered behind many of the presentations and

discussions.

Predictably, the Nashville seminar yielded mixed results. According to

Carmichael, “Folks were, depending on their inclinations, in turn suspicious,

flattered, surprised, confused, or all of the above simultaneously.” For some

of the student participants, mingling with academic stars and government

officials had the desired effect. For others, the experience only reinforced the

suspicion that the administration and its allies were bringing undue pressure

to bear on the student movement. This suspicion was most apparent among

the Freedom Riders, “all of whom,” according to John Lewis, “spoke firmly

in defense of sticking to our roots.” To Lewis and the others awaiting trial in

Jackson, “the matter was simple. We had gotten this far by dramatizing the

issue of segregation, by putting it onstage and keeping it onstage. I believed

firmly that we needed to push and push and not stop pushing. . . . I believed

in drama. I believed in action. Dr. King said early on that there is no noise as

powerful as the sound of the marching feet of a determined people, and I

believed that. I experienced it. I agreed completely with Diane and the others,

at least at that time, that this voter registration push by the government was

a trick to take the steam out of the movement, to slow it down.”

18

When the SNCC leaders gathered at Highlander on Friday, August 11,

it became clear that the factional line between direct action and voting rights

advocates had hardened since the Baltimore meeting. Convened on the eve

of the mass return to Jackson, the Highlander meeting promised to live up to

its dramatic setting in the mountains of southeast Tennessee. Founded in

1932 by labor activists Myles Horton and Don West, the legendary folk school

had hosted scores of important meetings over the years, including several

interracial workshops for student activists in 1960 and early 1961. But none

was more significant than the SNCC showdown of August 1961. Several of

the SNCC leaders had been to Highlander before, and they knew that it was

a place for open discussion and honest disagreement. As the discussions deep-

ened over the weekend, some worried that SNCC was in danger of dividing

into two separate organizations or of disappearing altogether. Jones and

Jenkins were adamant that voting rights should be SNCC’s first priority,

while Nash, Lewis, and the Freedom Rider faction were no less certain that

direct action represented the heart and soul of the organization and the move-

ment. Fortunately, Ella Baker was on hand to serve as a mediating influence,

just as she had done at SNCC’s founding conference in Raleigh fourteen

months earlier. On Sunday, after nearly three days of wrangling, Baker, the

398 Freedom Riders

one veteran organizer trusted by both factions, fashioned a workable com-

promise that divided SNCC into two equal “wings.” Nash, everyone agreed,

would lead the direct action wing, and Jones would lead the voter rights wing.

Though no one was completely satisfied with this division, most, including

Bernard Lafayette, tried to make the best of the situation. Assuming his usual

calming role, Lafayette reminded his departing colleagues that “a bird needs

two wings to fly.”

19

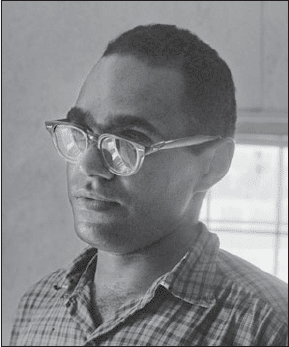

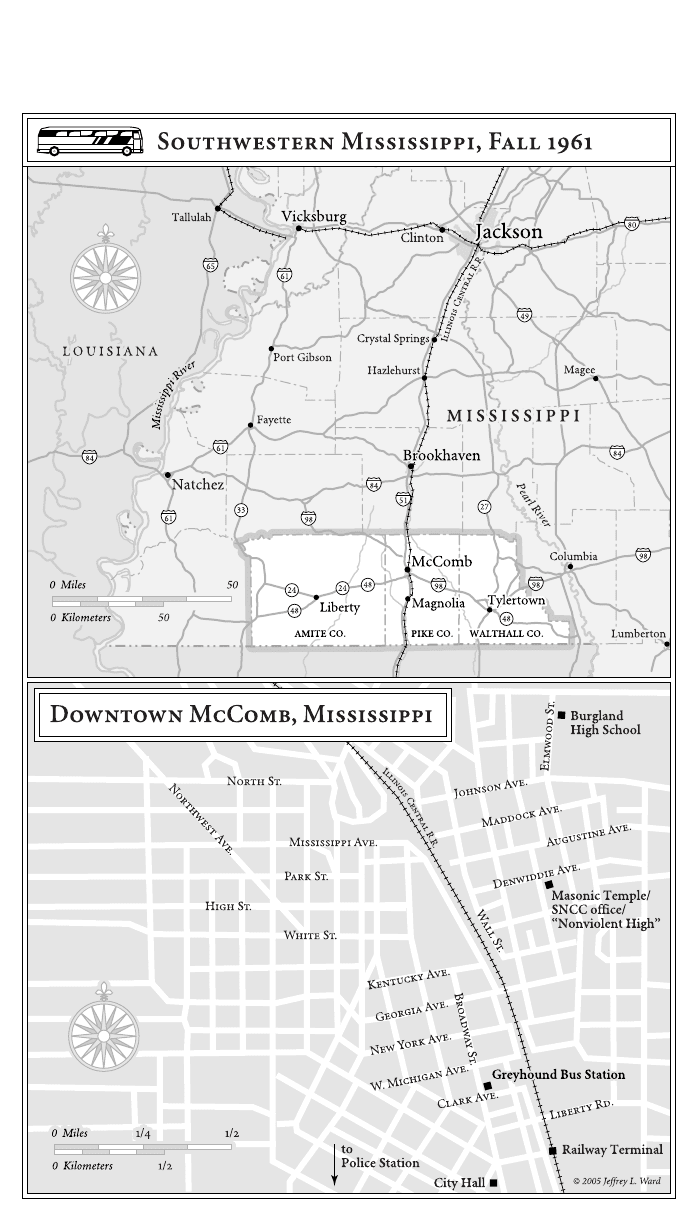

The creation of SNCC’s voting rights wing would have a profound im-

pact on the student movement in the months and years to come, but for

Sherrod and Moses the decision at High-

lander simply formalized what they had

already begun. After meeting with

Moses and Amzie Moore in Mississippi,

Sherrod traveled to southwest Georgia

to lay the groundwork for a multicounty

voter registration project. Moses, fol-

lowing Moore’s suggestion, set up shop

in McComb, establishing a voter regis-

tration school on the second floor of a

black Masonic temple. Moses’s “educa-

tional” experience included a childhood

in Harlem, four years at Hamilton Col-

lege in upstate New York, summer in-

ternships in France and Japan, a stint at

Harvard, where he earned an M.A. de-

gree in philosophy, two years of teach-

ing high school math in suburban

Westchester County, and participation in the Atlanta sit-in movement. But

nothing in his background had fully prepared him for the challenge of bring-

ing democracy to southwestern Mississippi.

Joined by John Hardy, a Tennessee State student from Nashville, and

Reggie Robinson, a SNCC activist from Baltimore, Moses spent two weeks

combing the local countryside for prospective students before opening the

school on August 7. Only a handful of students showed up that first night,

but four of them bravely agreed to try to register at the county courthouse in

Magnolia the next day. To their and Moses’s surprise, three of the four were

allowed to register. After a second night of classes, two more gained regis-

tered voter status. Encouraged, Moses accompanied nine more potential reg-

istrants to the courthouse on August 10, but this time only one new voter was

registered. Alarmed by this unusual surge of interest in voting, the registrar

contacted the editor of the McComb Enterprise-Journal, who promptly ran a

story informing local segregationists that something sinister was afoot.

Over the next few days, news of Moses’s school spread throughout the

local white community. Ironically, the story in the Enterprise-Journal also

Bob Moses, 1962. (Photograph by

Danny Lyon, Magnum)

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 399

alerted hundreds of local blacks, most of whom had been unaware of Moses’s

recruitment activities. Suddenly, Moses found his citizenship classes swell-

ing with new recruits, including a number of black farmers from the neigh-

boring counties of Amite and Walthall, areas that had even fewer black voters

than McComb. Compared to the semi-urban setting of Pike County, Amite

and Walthall were rural backwaters that posed an even more daunting chal-

lenge to Moses’s fledgling voting rights project. Extending the project be-

yond Pike County was both dangerous and logistically difficult, but, after

consulting with C. C. Bryant, Moses concluded that his credibility rested

upon his willingness to tackle even the toughest challenges. Thus, less than a

week after opening the school in McComb, he temporarily moved his base of

operations to Amite, where there was only one black voter in the entire county

and where the local NAACP branch had been driven underground by the

local sheriff. When E. W. Steptoe, the fearless leader of the defunct Amite

NAACP, offered Moses room and board at his farmhouse, the SNCC orga-

nizer gratefully accepted. And by Tuesday morning, August 15, the same

morning that saw the opening of the ICC hearings in Washington, Moses

found himself accompanying three prospective black voters—an elderly man

and two middle-aged women—to the Amite County Courthouse in Liberty.

The four black visitors caused quite a stir at the historic courthouse that

had graced the Liberty town square since 1840. Constructed of bricks “fired

by slaves” and flanked by a twenty-foot-high Confederate monument, the

building symbolized the white power structure of a Black Belt county that

was unaccustomed to contact with outsiders of any kind. To the registrar and

the other county officials who came to gawk at Moses and his three local

charges, the notion of a black voter registration project led by a New Yorker

was almost beyond comprehension. Still, after making his visitors wait for

several hours, the registrar allowed the three applicants to fill out the neces-

sary registration forms. While there was no suggestion that their applica-

tions would actually be approved, they left the courthouse with the satisfaction

that they had recaptured a certain amount of dignity just by applying. Unfor-

tunately, their sense of accomplishment was soon dispelled by a state trooper

who forced their car to the side of the road and then ordered them to follow

him back to McComb. Once there the three applicants were released and

allowed to return home, but Moses was placed under arrest, charged with

interfering with the trooper’s discharge of his duties. After a brief phone

conversation with John Doar of the Justice Department, who had assured

him in mid-July that the federal government would protect voting rights

workers and potential registrants from intimidation and interference, Moses

was taken before a local justice of the peace, who quickly rendered a guilty

verdict carrying a fifty-dollar fine. Refusing on principle to pay a fine levied

for unjust purposes, Moses was taken to the Pike County Jail in Magnolia,

where he remained until an NAACP attorney from Jackson paid the fine

three days later.

400 Freedom Riders

After grudgingly accepting the NAACP’s intercession on his behalf,

Moses returned to McComb to discover that his arrest had triggered a flurry

of activity among his SNCC colleagues. During his brief imprisonment,

Sherrod, Ruby Doris Smith, and several other Freedom Riders had rushed

to McComb, and others, including Charles Jones and Marion Barry, were on

the way. Coming on the heels of the Highlander meeting and the mass ar-

raignment in Jackson, Moses’s arrest had prompted an immediate response

from student activists determined to sustain SNCC’s widening involvement

in voting rights activity. Intent on sending a clear message that arrests and

attempts at intimidation would only strengthen SNCC’s resolve to register

black voters, Sherrod and the other new arrivals turned McComb into a full-

fledged movement center. While Moses himself shuttled back and forth be-

tween Pike and Amite Counties over the next few days, others greatly expanded

the activities of the McComb citizenship school—planning sit-ins, recruit-

ing high school students, and all but daring local white supremacists to try to

stop them.

20

With Steptoe’s help, Moses set up a makeshift citizenship school in a

black Baptist church hidden deep in the woods of Amite County. But, fol-

lowing the arrest, it was difficult to find volunteers brave enough to face the

registrar in Liberty. Each night Moses held forth on the responsibilities of

citizenship and the necessity of challenging the white stranglehold on county

politics, but it took almost two weeks for him to find anyone willing to ac-

company him to Liberty. On the morning of August 29, he escorted two

applicants, a respected middle-aged farmer named Curtis Dawson and an

elderly man known locally as Preacher Knox, to the courthouse. Waiting on

the sidewalk outside the entrance were three white men, including Billy Jack

Caston, the son-in-law of Amite County’s most outspoken white suprema-

cist, State Representative E. H. Hurst. After demanding to know why three

black men wanted to enter the courthouse, Caston struck Moses in the face

with a knife handle, knocking him to the pavement. After getting in a few

more blows, Caston ran off, leaving a dazed and bleeding Moses with three

gashes in his head. Undaunted, Moses led Knox and Dawson in to see the

registrar, who, upon seeing the blood pouring from Moses’s wounds, promptly

closed the office.

Following a brief stop at Steptoe’s farm, Dawson drove Moses back to

McComb, where they found a black doctor willing to stitch up Moses’s

wounds, and where they discovered that the town was about to experience its

first mass meeting. Earlier in the day two local students, Hollis Watkins and

Curtis Hayes, had been arrested during a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch

counter, prompting Marion Barry to call a meeting to take advantage of the

rising outrage among the town’s black citizens. The featured speaker was

Jim Bevel, who inspired a crowd of nearly two hundred with resounding pleas

for righteous struggle. The high point of the evening, however, proved to be

Moses’s plaintive and powerful testimony relating the events at the Liberty

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 401

402 Freedom Riders

courthouse. Urging the audience to bear witness to the power of the move-

ment, he vowed to continue the fight, a pledge he promptly fulfilled the next

morning. Filing a formal complaint against Caston with the Amite County

prosecutor, he soon found himself testifying in front of an all-white jury and

an angry white crowd that not only filled the courtroom but also spilled out

onto the same sidewalk where he had been assaulted two days earlier. Fol-

lowing the trial—which had little impact on the jury, judging by the acquittal

rendered the next day—Moses walked down the hall to greet Freedom Rider

Travis Britt, who had accompanied an elderly black farmer named

Weathersbee to the registrar’s office. Just as Moses was about to shake Britt’s

hand, the sound of a shotgun blast forced everyone in the hallway to duck for

cover. While no one was injured, the incident convinced the sheriff that it

was wise to hustle Moses out of the county before someone got killed.

Moses and his companions made it back to McComb in one piece, but

the situation there was only slightly less threatening. The white community

was outraged over an attempt to desegregate the lunch counter at the city’s

Greyhound terminal. The day after the mass meeting, three local students—

Bobbie Talbert, Ike Lewis, and Brenda Travis—had put Bevel’s words into

action, and the police had responded by putting all three in the city jail. The

fact that Travis was only fifteen years old was cited as proof that the Freedom

Rider–inspired protest was both irresponsible and dangerous, and that the

movement had taken advantage of the community’s children. At the same

time, her incarceration in an adult facility infuriated local black leaders who

feared that this was the beginning of a no-holds-barred defense of segrega-

tion. Both sides, it appeared, were preparing for a protracted struggle over

desegregation, something that had been almost unthinkable in McComb prior

to the arrival of Moses and SNCC. It was a scenario that C. C. Bryant had

dreamed about for years but had never really expected to see. Now that the

movement whirlwind had descended upon Pike County, Bryant was not sure

that he or anyone else was completely ready for the revolution that loomed

on the horizon. But he was confident that Pike and the neighboring counties

of southwestern Mississippi would never be quite the same again.

The shift had begun with Moses’s arrival in McComb, but the proximate

catalyst of the new era was the critical mass of outsiders who had turned

Moses’s voting rights project into the Pike County Nonviolent Movement.

Although Moses himself had doubts about the viability of the makeshift move-

ment initiated in his absence, there was no turning back. Even in the remot-

est corner of the state, the fallout from the arrest and imprisonment of

hundreds of committed activists had penetrated the previously impenetrable

walls of segregationist complacency. Here, as elsewhere, the involvement of

Freedom Riders added volatility to the situation, confounding traditional pat-

terns of accommodation and compromise. Wherever the Freedom Riders

showed up during the late summer and fall of 1961—from McComb, Missis-

sippi, to Albany, Georgia, to Monroe, North Carolina—the spirit of nonvio-

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 403

lent direct action empowered and energized local black movements, creating

an interlocking chain of movement centers. Both before and after their ap-

pellate trials in Jackson, restless Riders offered their services as nonviolent

shock troops, confirming the suspicion that the Freedom Rides represented

the opening campaign of an all-out assault on the Jim Crow South.

21

BY THE END OF THE YEAR the diffusion of Freedom Riders would help to turn

Mississippi and southwestern Georgia into major civil rights battlegrounds,

but nothing demonstrated the widening impact of the Freedom Rides more

clearly than the developing situation in the North Carolina Piedmont town

of Monroe. Destined to be the most controversial episode of the Freedom

Rider saga, the Monroe Freedom Ride was the by-product of a personal mis-

sion undertaken by two of the movement’s most independent activists, Paul

Brooks and Jim Forman. Born in East St. Louis, Illinois, to parents who had

migrated from DeKalb, Mississippi, Brooks was a divinity student at Ameri-

can Baptist in Nashville before becoming a full-time activist in the spring of

1961. After participating in the Birmingham and Montgomery Freedom Rides,

he moved to Chicago to coordinate the FRCC’s Midwestern fund-raising

efforts. Soon after his arrival in late May, he met Forman, a thirty-three-

year-old ex-schoolteacher who had become active in a campaign to provide

relief for black voting rights advocates in two counties in western Tennessee,

Fayette and Haygood. Though born in Chicago, Forman had spent part of his

childhood in Mississippi. After graduating from Roosevelt University, where

he was elected student body president in 1956, he did graduate work in African

studies at Boston University before returning to Chicago to teach at an el-

ementary school. Along the way he worked as a reporter for the Chicago De-

fender during the 1957 Little Rock crisis, wrote an unpublished novel depicting

an interracial nonviolent movement, and acquired a growing reputation as a an

outspoken and freewheeling black intellectual.

In November 1960 Forman visited western Tennessee as part of a two-

person fact-finding team. His companion was Sterling Stuckey, a young folk-

lore scholar and Chicago CORE leader who had spearheaded the formation

of the Emergency Relief Committee, a CORE project organized as a re-

sponse to a White Citizens’ Councils effort to starve black voting rights ad-

vocates into submission. The desperate situation in Fayette County, where

many black families were living in tents after being displaced from their homes

by white landlords, shocked Forman and Stuckey, but after their return to

Chicago an effort to expand the Emergency Relief Committee led to per-

sonal and political bickering and the eventual dissolution of the committee.

Disgusted with the internal politics of Chicago CORE but determined to

continue the relief effort, Forman organized a new relief organization, the

National Freedom Council, in March 1961. Comprised primarily of Forman’s

friends and fellow teachers, the National Freedom Council had some success

in gathering funds and supplies, and in raising awareness about the economic

404 Freedom Riders

plight of western Tennessee’s voting rights activists. By midsummer the situ-

ation seemed to be improving, though hundreds of evicted black farmers

were still living in a sprawling tent city. In January the Justice Department

had obtained a temporary restraining order prohibiting such evictions, and

the department had subsequently filed voting rights suits in both counties.

But the ultimate economic and political fate of those involved in the Fayette

and Haygood movements was still very much in doubt in early July, prompt-

ing Forman to return to Tennessee to see for himself.

22

The night before he boarded a train for Memphis, Forman paid a visit to

Brooks and Catherine Burks, who had just arrived in Chicago after her re-

lease from Parchman. Both Brooks and Burks, his girlfriend and future wife,

were staying at the home of a friend of Forman’s—University of Chicago

professor Walter Johnson—and Forman was eager to meet the young woman

who had refused to be intimidated by Bull Connor in Birmingham. For a few

minutes Forman talked about the National Freedom Council and what he

expected to encounter in Tennessee, but mostly he listened attentively as the

two Freedom Riders described their recent experiences in the nonviolent

movement in the Deep South. Both were sharply critical of the majority of

black Southerners, most of whom refused to join or openly endorse the

struggle for desegregation and social justice. Brooks and Burks were espe-

cially critical of middle-class blacks, including some who “are always ready to

talk about civil rights but who seldom, if ever, commit themselves to positive

acts to end segregation.” To Forman’s surprise, they also expressed strong

reservations about the viability of nonviolence as an all-encompassing move-

ment strategy. Brooks, in particular, seemed open to the argument that South-

ern blacks should not rule out armed self-defense as a necessary part of the

struggle for freedom. This argument was anathema to many of Brooks’s closest

friends in the movement—including his American Baptist Theological Semi-

nary classmates John Lewis, Jim Bevel, and Bernard Lafayette—but in recent

weeks Brooks had grown increasingly disillusioned with both the philosophy

and the leadership of the nonviolent movement. Profoundly disappointed by

Martin Luther King’s refusal to become a Freedom Rider, he had under-

taken a personal search for a less hypocritical and more realistic model of

movement leadership—a search that ultimately led him to the South’s most

controversial black leader, North Carolina’s Robert Williams.

23

Brooks’s fascination with Williams demonstrated just how far he had

traveled in a few short weeks, from the inner circle of Jim Lawson’s nonvio-

lent apostles to a flirtation with the outer fringe of radical politics. For more

than two years, Williams and the Monroe NAACP had been engaged in an

ongoing and high-profile struggle with both local segregationists and na-

tional civil rights leaders alarmed by his advocacy of “armed self-reliance.”

Since his celebrated censure by a large majority of the delegates to the 1959

NAACP national convention, he had grown even more militant, openly chal-

lenging the Jim Crow system at every opportunity and roundly condemning

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 405

moderate leaders for their empty words and lack of resolute action. Refusing

to abide by the conventional rules of practical and Cold War politics, he

attracted a loyal following among black radicals, especially in Harlem, where

community activists such as Mae Mallory and black intellectuals such as nov-

elist Julian Mayfield and historian John Henrik Clarke welcomed his un-

abashed militance as a refreshing alternative to liberal inaction and caution.

In 1960 Williams became a key figure in the radical Fair Play for Cuba Com-

mittee, defending Fidel Castro as a visionary exponent of social and racial

democracy; and by the spring of 1961 he was punctuating his speeches with

revolutionary rhetoric that came dangerously close to a call to arms. “I am

going to meet violence with violence,” he told a Harlem crowd on May 17,

the seventh anniversary of Brown. “It is better to live just thirty seconds,

walking upright in human dignity, than to live a thousand years crawling at

the feet of our oppressors.”

Those who knew Williams well recognized that such rhetoric was less a

celebration of violence than a reflection of his continuing frustration with

local officials who refused to protect him and other Monroe blacks from

marauding Klansmen. As Brooks explained to Forman in mid-July following

a phone conversation with Williams, the Klan had tried to kill the Monroe

civil rights leader after he had led an attempt to desegregate a public swim-

ming pool in the summer of 1960. The local police knew the identity of the

assailant, Williams insisted, but refused to make an arrest. Feeling vulner-

able and alone, Williams asked Brooks and other outsiders for help. Intrigued,

the young Freedom Rider decided to conduct a personal investigation of the

situation in Monroe. After further conversations with Williams, Forman, and

movement friends in Nashville, Brooks sought and received an endorsement

for the trip from both SCLC and the National Freedom Council. The lead-

ers of the Freedom Council urged Forman to accompany Brooks, and on

Friday, July 21, the two men set out for Monroe via Nashville and Atlanta.

24

In Nashville, where they stopped off for more than a week, Brooks and

Forman found themselves in the midst of a movement hothouse. At the Nash-

ville Movement office, they spent several days discussing movement philoso-

phy and strategy with Nash, Bevel, Lafayette, and several other SNCC and

SCLC activists who had recently returned from Mississippi. Much of the

discussion, Forman recalled, revolved around a series of interrelated issues:

the difficulty of provoking and sustaining a mass movement among Missis-

sippi blacks; the necessity of overcoming the relative timidity and organiza-

tional inertia of groups such as the NAACP and SCLC; the future of SNCC

and the central role of student activists in the expanding struggle for free-

dom and social justice; the tactical and philosophical viability of nonvio-

lence; and the advisability of shifting the movement’s focus from direct

action to voting rights. This last issue was currently the major topic of

conversation at the student movement workshop convened at Fisk on July

30, and before leaving town on August 2, Forman and Brooks participated