Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

386 Freedom Riders

and the Southern way of life. For many segregationists the local and regional

struggle against Freedom Riders and other “outside agitators” was inextrica-

bly bound to the international struggle against Soviet tyranny. And nowhere

was the mutual reinforcement of segregationist anxieties and Cold War ten-

sions more obvious than in Jackson, especially in the weeks leading up to the

Freedom Rider trials.

6

With the temporary suspension of the Freedom Rides, Jackson’s bus and

train terminals entered a period of relative calm in early August. But this

hiatus did not extend to the city’s courtrooms, where a series of heated legal

confrontations created a warlike atmosphere. Fought on segregationist soil,

the legal war between local prosecutors and movement attorneys was a de-

cidedly unequal struggle skewed by powerful racial and regional traditions.

Initially, Jackson city officials “had agreed to the customary procedure in

mass arrests, requiring only one or two typical cases to show for arraignment

and trial and applying the findings in those cases to all the others,” but in late

July, in an obvious attempt to ensnare CORE and the FRCC in a financially

burdensome legal tangle, the city’s attorneys reneged on the agreement. In-

stead of a few representative defendants, all of the Freedom Riders out on

bail would now be required to return to Jackson by August 14, the designated

arraignment date, “on pain of forfeiting the five-hundred-dollar bond CORE

had put up on each.” City prosecutor Jack Travis and other local officials

made no secret of their intentions. “We figure that if we can knock CORE

out of the box, we’ve broken the back of the so-called civil rights movement

in Mississippi,” Travis informed CORE attorney Jack Young, “and that’s

what we intend to do.” Dragging out the trials, making them as costly as

possible, and generally keeping the defendants and their attorneys off bal-

ance were all part of a strategy designed to sap the movement’s energies and

resources.

7

Bringing nearly two hundred defendants back to Jackson by mid-August

was a daunting task, but movement leaders had no other way of avoiding a

financially crippling forfeiture of one hundred thousand dollars or more. At

an emergency meeting on Thursday, August 3, the FRCC authorized Carl

Rachlin and William Kunstler to meet with Hinds County Judge Russel Moore

in the hope that he would overrule the decision to require all of the Riders to

appear in court both on the day of arraignment and on their individual trial

dates. On the following Wednesday, during a special conference with Moore,

the two attorneys argued that representative proceedings were not only fairer

but safer than the proposed mass return. “We are here to try to assure an

orderly trial,” Rachlin insisted, suggesting that a mass return of Freedom

Riders “might spark an ‘irresponsible act’ by white Mississippians.” When

Judge Moore turned them down, Rachlin and Kunstler filed an appeal with

Circuit Judge Leon Hendrick, urging a compromise that would eliminate

the requirement to appear at the August 14 arraignment. “All are ready and

willing to come back for their trials as they come up,” Kunstler maintained,

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 387

but “to make them come when the calendar is called and again for their trials

is a harassment on the part of the state.” Forcing the defendants to appear

twice would cost CORE an estimated twenty thousand dollars in unneces-

sary expenses, he explained. Unmoved, Judge Hendrick advised the Free-

dom Riders to be in court on August 14 or suffer the consequences. Later in

the day, after Judge W. N. Ethridge of the Mississippi State Supreme Court

turned down a request to overrule the lower court judges, Kunstler threw in

the towel. “This is it,” he informed the press. “There are no more appeals.

I’ve called and told them to have all the defendants here for the opening of

the term.”

8

The rebuff from Mississippi’s highest court on August 10 capped off a

week of legal setbacks for the Freedom Riders. Earlier in the week the Justice

Department had refused CORE’s request for the placement of federal mar-

shals at the upcoming trials in Jackson, and on Monday, August 7, Judge

Robert Rives, speaking for a three-judge panel of the Fifth Circuit Court of

Appeals, had granted a six-week delay in the NAACP’s suit against Jackson’s

municipal breach-of-peace law. Dismissing the objections of NAACP attor-

ney Constance Baker Motley, who had asked for a temporary injunction that

would forestall any further arrests under the law, the court scheduled the

next hearing on the matter for September 25. Motley’s co-counsel in the

suit, Justice Department attorney Robert Owens, was present in the court

room when the ruling was handed down, but neither he nor any other federal

official offered an opinion on the wisdom of the delay. Once again it ap-

peared that the Justice Department was eager to avoid any precipitous or

provocative action that might be construed as a challenge to the integrity of

the legal process in the Deep South.

9

FRCC leaders had no such reservations and continued to question the

fairness of a legal system that harassed and intimidated anyone who chal-

lenged the segregationist order—a system that they hoped would soon dis-

appear. For the time being, however, they had no choice but to comply with

the requirements of that system. Anticipating the unfavorable court rulings,

Jim Farmer and the staff of the CORE office had been preoccupied with the

task of rounding up the Freedom Riders since the beginning of August. “I

put the organization on an emergency basis,” he later recalled, “canceling all

leave and ordering that staff, including myself, be on call for duty around the

clock and reachable by phone. Many of the Riders were mobile persons of

tenuous roots. . . . Tracking them down would be no small task. Yet, locating

the scattered army was perhaps the least of our problems. There was also the

matter of getting them to central checkpoints, onto chartered buses to Jack-

son, where we would have to feed and house them for an indeterminate stay,

and then get them back to their homes. The cost of that operation would be

staggering and as open-ended as Mississippi chose to make it.”

Although Farmer and other movement leaders were reluctant to say so

publicly, much more than money was at stake. The Freedom Riders’ public

388 Freedom Riders

image and the integrity of the nonviolent movement were also on the line. If

a substantial number of Freedom Riders failed to return to Mississippi for

trial, there would be widespread speculation that the missing Riders were

afraid to return, that fear or other personal considerations had outweighed

their commitment to the struggle. Whatever the real reasons for the failure

to appear, the suspicion that the Freedom Riders lacked faith or courage was

potentially devastating to a movement that trafficked in moral capital. No

element of the movement’s mystique was more compelling than the drama

of personal sacrifice, and no aspect of nonviolent direct action was more es-

sential than individual accountability. Thus there was no allowance for ex-

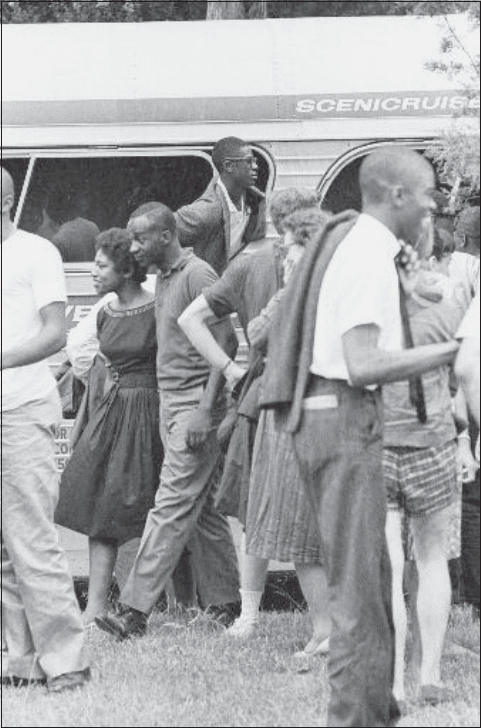

Freedom Riders arrive in Jackson for their arraignment on

August 14, 1961. The man with his arm around a young

woman is John Moody Jr. The man sticking his head out of

the bus window is Clarence Thomas. (AP Wide World)

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 389

cused absences. Realizing this simple truth, Farmer and his colleagues spared

no effort in the campaign to retrieve the scattered Freedom Riders. With

Marvin Rich skillfully coordinating an emergency fund raising effort and

with the rest of the staff and volunteers focusing on the logistics of contact-

ing and transporting the defendants, CORE was able to retrieve 192 of the

released Freedom Riders. Only nine Riders failed to appear for arraignment

on August 14, and three of those arrived a day late after being detained by

the New Orleans police, leaving only six actual forfeitures. One of the six

could not be found, and two others—one in northern Saskatchewan and a

second in Turkey—were simply too far away to return to Jackson in time.

The sheer number of returning Freedom Riders was impressive, but

CORE’s greatest accomplishment was the orderly and uneventful nature of

the mass return. Following a carefully orchestrated plan, the vast majority

of the Riders arrived in Jackson either on the Saturday or Sunday just prior

to the Monday arraignment. Instructed to avoid individual acts of conscience

or other provocative acts, the Riders slipped into the city as quietly as pos-

sible before being whisked away to their overnight accommodations at

Tougaloo College or in private homes. Fortunately, local and state officials

were equally determined to maintain the peace. Deployed in full force, the

Jackson police, sheriff’s deputies, and state troopers kept any potential at-

tackers away from the terminals and from Tougaloo. The only violent inci-

dents marring the mass return occurred outside of Mississippi.

In New York City, Marvin Rich and Marvin Doolittle, a reporter for the

New York Post, were struck by a white assailant on Friday morning after Rich

put Farmer and thirty other returning Riders on a southbound bus. Later the

same day, in Houston, Texas, eighteen new Freedom Riders were arrested

after trying to desegregate a railway terminal coffee shop. Eleven were Cali-

fornians who had just arrived on a train from Los Angeles, and seven were

members of the Progressive Youth Association, a local black protest group

that had been trying to break the color line at the coffee shop and other

downtown Houston restaurants for several months. Some of the Riders were

roughed up by the police, and four of the Californians—Bob Kaufman, Steve

McNichols, Steve Sanfield, and Joe Stevenson—ended up in a “white male

misdemeanor tank” that, according to McNichols, “was dominated by a small

band of hardened criminals who shared common homosexual and sadomas-

ochistic bonds.” “You must be those fuckin’ nigger lovers,” one inmate shouted

as the four Riders entered the cell block. Two days of intimidation and inter-

mittent terror followed, and by the time they bailed out on Sunday they had

seen enough of the Texas penal system to last a lifetime. The other fourteen

Riders remained in jail until the following week, and all eighteen were even-

tually convicted of unlawful assembly, a judgment later nullified by the Texas

Court of Criminal Appeals.

To the surprise of many, there were no such violent episodes or mass

arrests in Jackson. When two new Freedom Riders— a young British woman

named Pauline Sims and George Raymond of New Orleans—were arrested

390 Freedom Riders

in the white waiting room of the Jackson Trailways terminal on Sunday morn-

ing, both the local police and the press tried to downplay the incident. Ear-

lier in the week the blind activist Norma Wagner, accompanied by Earl

Bohannon Jr., a black Freedom Rider from Chicago, had made a second at-

tempt to get arrested at the same terminal, but once again the police refused

to arrest her. Frustrated after sitting at the black lunch counter for several

hours, she caught a bus to New Orleans, where she was finally arrested two

days later for distributing CORE leaflets in a black neighborhood. Trum-

peted by the Mississippi press, this story symbolized the surprising calm that

Jackson enjoyed in the days leading up to the mass arraignment.

10

On Sunday evening the mood in Jackson was calm enough to allow move-

ment leaders to hold a mass “freedom rally” at the same black Masonic Temple

where Martin Luther King had spoken five weeks earlier. Sponsored by the

Jackson Non-Violent Movement, the rally drew more than a thousand sup-

porters, including virtually all of the returning Freedom Riders. Following

an afternoon planning session at Tougaloo, the Riders traveled to the down-

town temple in a caravan of cars, avoiding any unnecessary stops, and they

were ushered into the hall through a cordon of police officers who kept the

surrounding area clear of white demonstrators. Once inside, they were greeted

by waves of applause from an overwhelmingly black audience dominated by

young student activists, some still in their early teens. During the next two

hours the Riders and their hosts “clapped, sang, and shouted” as a series of

speakers representing the NAACP, CORE, SCLC, and the Jackson Move-

ment held forth. With several national reporters looking on, Farmer told the

crowd that they were part of a growing national movement for freedom. The

morning after he had left New York, more than three hundred CORE sup-

porters had gathered at the foot of the Statue of Liberty to praise the Free-

dom Riders, and later in the day many of the same activists, black and white,

had joined a twenty-four-hour “Fast for Freedom” in Battery Park. This was

the spirit that had propelled the Freedom Rides into the national limelight,

he insisted, a spirit that was alive and well in Jackson. By forcing the mass

return of the Freedom Riders, Mississippi officials had unwittingly saved a

movement that had almost “run out of steam.” The return to Jackson had

pumped new life into the Freedom Rides, “which now must continue no

matter how much it costs.”

Representing SCLC, Wyatt Tee Walker followed Farmer’s speech with

a special greeting from Martin Luther King. Dr. King wished that he could

be there with them, Walker declared, but the needs of the movement re-

quired him to be in New York to deliver a “freedom” sermon at the Riverside

Church. As a round of amens filled the hall, Walker went on to hail the

Freedom Riders as heroes and later entertained the crowd with a revised

“movement” version of the minstrel song “Old Black Joe.” The new words,

according to Walker, were “I’m coming, I’m coming, And my head ain’t

bending low. I’m coming, I’m coming, I’m America’s new Black Joe.” Al-

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 391

though he did not explain the song’s relevance in so many words, the mes-

sage was clear: The Freedom Riders had come to Jackson, and they were not

leaving until both Jim Crow and Old Black Joe were dead and gone. Carried

along by Walker’s booming voice, this ringing expression of hope and pur-

pose capped off an emotional evening of individual and collective renewal.

For the Freedom Riders themselves, these feelings of emotional uplift would

soon be tested by the challenges of a hostile courtroom. For their local sup-

porters, there would be even greater tests imposed by a rigidly segregated

society. But no one present at the Masonic Temple that evening left the hall

without at least some appreciation for the rising power of the movement.

11

One index of the civil rights movement’s rising power was its ability to

draw national and international press coverage, but in this instance the cov-

erage was relatively thin, largely because much of the nation and the world

was preoccupied with the construction of the Berlin Wall earlier in the week-

end. In Jackson and a few other Deep South communities, the mass return

and arraignment of the Freedom Riders earned front-page headlines. Else-

where, however, the story was buried in the back pages, robbing Judge Russel

Moore of his chance for worldwide celebrity.

The scene at the Hinds County Courthouse on Monday, August 14, was

rife with tension, but the soft-spoken judge did his best to maintain legal

decorum and the appearance, if not the reality, of judicial neutrality. Early in

the day, he convened a special arraignment for Percy Sutton and Mark Lane,

two high-profile Freedom Riders scheduled to return to New York on an

early afternoon plane. Both men pleaded not guilty, as did all of the defen-

dants who later appeared at the regular 2:00

P.M. arraignment. At the begin-

ning of the afternoon session, Kunstler filed several defense motions, including

a declaration that the local statutes involved in the Freedom Rider arrests

“were unconstitutional on their face and a violation of the U.S. Constitution,”

a call for a “class action” streamlining of the court’s appellate procedures, and

a demand for a change of venue to the “furtherest county in the state from

Hinds.” After swiftly rejecting all of Kunstler’s motions, Judge Moore brought

the defendants forward in pairs to register their pleas and assign trial dates.

Following a prearranged agreement grudgingly accepted by Kunstler, the judge

scheduled two appellate trials a day, beginning with Hank Thomas and Julia

Aaron on August 22. Collectively, the scheduled trials filled twenty-two weeks

of the court’s docket, stretching into mid-January 1962. By five o’clock the

mass arraignment was over, bringing temporary relief to the defendants who

now knew when they had to return to Mississippi. Having seen enough of

Mississippi justice for one day, most filed out of the courtroom as quickly as

possible, and many left the state before nightfall.

12

JUDGE MOORE’S RULINGS set a difficult course for CORE and the Freedom

Riders. In the short term, the scheduled appellate trials would consume vir-

tually all of CORE’s resources, making it all but impossible to extend the

392 Freedom Riders

Freedom Rides to other areas of the South. And, with more than a hundred

additional Freedom Riders languishing in Mississippi jails, there would al-

most certainly be many more trials to follow. Barring timely intervention by

the federal courts, the legal tangle related to the Jackson arrests would take

months, and even years, to unravel. To CORE stalwarts, this burden was an

unfortunate but necessary part of conducting nonviolent direct action on a

mass scale. But to many others, both inside and outside the movement, the

mounting costs and uncertain future of the Freedom Rides seemed to con-

firm the wisdom of less disruptive approaches to social change. Publicly, the

leaders of the NAACP and SCLC pledged their support to the legal battle

being waged in Jackson. Privately, however, they expressed grave doubts about

any strategy that placed the fate of the movement in the hands of segrega-

tionist judges.

Officials at the Justice Department were even less sanguine about the

legal situation in Mississippi. Earlier in the summer Robert Kennedy and his

colleagues had placed their faith in the Interstate Commerce Commission,

and the events of July and early August had done nothing to alter their belief

that the long-neglected but potentially powerful regulatory agency would

eventually provide a politically and legally palatable solution to the Freedom

Rider crisis.

Most movement leaders doubted that the present ICC commissioners

had either the will or the capacity to desegregate public transit facilities. But,

whatever their expectations, they recognized the symbolic and political im-

portance of the ICC hearings that opened in Washington on Tuesday, Au-

gust 15, less than twenty-four hours after the mass arraignment in Jackson.

On the Sunday afternoon following his speech at the Riverside Church, King

challenged the ICC to issue a sweeping ruling that included a “blanket or-

der” against segregation in bus, rail, and air terminals. “The Freedom Rides

have already served a great purpose,” he told reporters, highlighting “the

indignities and injustices that the Negro people still confront as they attempt

to do the simple thing of traveling as interstate passengers.” He acknowl-

edged, though, that a clear and broad ICC mandate held the power to go

even further. If strict compliance were enforced for interstate travelers, all

segregated travel would “almost inevitably end,” even among intrastate trav-

elers. “This will be the point where Freedom Rides will end,” he predicted.

The ICC had already received similar advice from hundreds of CORE

supporters who had either signed petitions or submitted letters endorsing

the Justice Department’s proposal for a comprehensive desegregation order.

To make sure that the commissioners realized what was at stake, CORE set

up a line of sign-carrying “Freedom Riders” outside the ICC building on the

first morning of the hearings. Inside the building, CORE’s chief counsel,

Carl Rachlin, was one of thirteen witnesses testifying before the commis-

sion. Following the lead of Justice Department attorney St. John Barrett,

who insisted that the ICC had the power and the duty “to halt discrimination

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 393

in this field,” Rachlin urged the commissioners to “apply a little moral force”

to the “wonderful, decent people” of the white South. “You must help them

to get rid of a tradition which is morally wrong,” he declared, with a wink,

“even though they oppose change at the moment.”

13

The oral arguments that began on August 15 initiated the public phase

of the ICC’s deliberations, but most of the groundwork for the deliberations

had already been laid in lengthy behind-the-scenes negotiations held in June,

July, and early August. The procedures established by the ICC in mid-June

set aside a month for the submission of written briefs and three additional

weeks for rebuttal statements. Representing the Justice Department, Burke

Marshall urged the commissioners to act with dispatch, and the department’s

brief filed on July 20 reiterated the comprehensive demands outlined in the

attorney general’s extraordinary May 29 petition. The attorney general wanted

nothing less than a broadly enforceable order that would supersede the in-

definite mandates of the Motor Carrier Act of 1935 and the obvious limita-

tions of the Morgan and Boynton decisions. Historically, the conflicting

provisions of state and federal laws on matters of Jim Crow transit had tilted

toward segregation, in part because only the state statutes included specific

commands. Thus meaningful desegregation would require a detailed and di-

rective order along the lines proposed by the attorney general. Although the

opposition of state and local officials to such an order was a given, Justice

Department officials hoped to persuade private bus companies and other in-

terstate carriers to support the administration’s position. After the briefs sub-

mitted in July indicated that the carriers had serious reservations about the

scope and coercive nature of the attorney general’s plan, Marshall invited

several transit industry executives to a closed-door meeting in Washington.

At the meeting the executives listened politely to what Marshall and other

Justice Department officials had to say, but in the end they were unwilling to

accept a comprehensive plan. The best they could do was to offer to with-

draw their opposition if the administration agreed to limit the plan’s regula-

tory power to vehicles and facilities specializing in interstate travel. Leaving

most of the Jim Crow transit system intact, this limitation was, as Marshall

explained, totally unacceptable to an administration looking for a way to end

rather than perpetuate the Freedom Rider crisis.

The failure to convert the transit executives was disappointing, but the

most important lobbying effort, the one that really mattered, was directed at

the ICC commissioners themselves. Since most of the commissioners were

Republicans appointed during the Eisenhower era, and only one—a Massa-

chusetts Democrat named William Tucker—was a Kennedy appointee, the

administration faced an uphill political struggle in its dealings with the noto-

riously prickly commission. Having Tucker on the commission was a plus,

but the others had to be approached with great care through essentially non-

political channels. Consequently, the administration mounted a broad-gauged

appeal that emphasized the national security aspects of the struggle for civil

394 Freedom Riders

rights. According to Marshall and several other high-ranking members of

the administration, the immediate need for a sweeping ICC desegregation

order transcended considerations of racial equity or legal precedent. In a

letter to the commissioners, Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara argued

that the enforcement of segregation on buses and trains posed a serious threat

to the morale of black military personnel assigned to Southern bases. A simi-

lar letter submitted by Secretary of State Dean Rusk, a native Georgian fa-

miliar with Southern laws and customs, insisted that the persistence of

segregated transit facilities was a major embarrassment for a nation promot-

ing democracy and freedom in a largely nonwhite world.

14

Reiterated by other administration officials throughout the summer of

1961, Rusk’s point received timely reinforcement from a series of diplomatic

incidents related to the recent proliferation of black African envoys to the

United States. As recently as 1959 the sub-Saharan diplomatic corps in Wash-

ington and New York had consisted of a small number of envoys represent-

ing Ethiopia, Liberia, and Ghana, but with the arrival of representatives from

more than two dozen newly independent African nations in 1960 and 1961,

the treatment of African diplomats by their American hosts became a subject

of intense interest and controversy. Most obviously, the racial segregation

that dominated the greater Washington area became an embarrassing reality

for the new Kennedy administration. The segregated housing patterns of the

District of Columbia, suburban Maryland, and northern Virginia proved to

be a major irritant for visiting African families. The primary flash point,

though, was the segregated facilities along the Route 40 corridor between

Washington and the New Jersey border. When traveling back and forth be-

tween Washington embassies and the United Nations headquarters in New

York, black Africans discovered that virtually all of the restaurants and other

public accommodations were for whites only.

After receiving a number of complaints from African delegations, the

State Department created the Special Service Protocol Section (SPSS) of the

Office of Protocol in March 1961. Headed by Pedro Sanjuan, a thirty-year-

old Cuban emigré and former Kennedy campaign worker with a Russian

studies degree from Harvard, the SPSS initially worked quietly behind the

scenes to smooth over any hard feelings. But, following a denial of service to

Adam Malik Sow, the new ambassador from Chad, in late June, Sanjuan dis-

cussed the Route 40 problem directly with President Kennedy, who autho-

rized an organized effort to convince restaurant owners and Maryland officials

that discrimination along Route 40 was harming the national image. By the

end of July several White House aides, including Harris Wofford and Fred

Dutton, had been enlisted in the effort to promote the desegregation of Route

40, setting the stage for a major public controversy that would eventually

involve CORE and a recalcitrant Maryland legislature. At the time of the

August ICC hearings, the public struggle over what was later known as the

Woke Up This Morning with My Mind on Freedom 395

Route 40 campaign had not yet begun, but it would soon become an impor-

tant part of the political backdrop that both the ICC and the Justice Depart-

ment had to take into account.

15

The increasingly obvious diplomatic implications of segregation pro-

vided administration officials with a degree of leverage in the effort to secure

an ICC desegregation order. The effort itself, however, was not something

that many officials relished. Although Marshall and others would eventually

come to appreciate the political and moral growth that the Freedom Rider

crisis forced upon them, the usefulness and advisability of nonviolent direct

action escaped them at the time. While recognizing the need for social change,

they strongly preferred less disruptive forms of civil activism such as bring-

ing test cases before the courts or conducting voter registration drives. En-

couraging movement leaders to deemphasize direct action techniques had

been on the administration’s agenda since the earliest days of the Kennedy

presidency, but the effort to make the civil rights movement more “civil”

took on a new urgency after the Freedom Rides provoked massive resistance

in the Deep South. As we have already seen, several meetings held in the

early summer brought black student leaders, white liberals, and Justice De-

partment representatives together for an ongoing discussion of the prospects

for a region-wide voting rights campaign funded by private foundations. Al-

though the discussion angered Diane Nash and other direct action advocates

who suspected that the administration was trying to blunt the radicalism of

the student movement with the promise of voting rights funding, a growing

number of student activists appeared willing to consider the proposed shift.

As the summer progressed, it became clear that the likelihood of such a

shift rested upon the organizational and ideological evolution of SNCC. When

SNCC’s central committee hired Charles Sherrod as the organization’s first

field secretary in June, it took an important step toward the actualization of a

voting rights project. Even though Sherrod was a strong advocate of direct

action, he also believed that SNCC should be actively involved in promoting

the registration of black voters. Less than a month after becoming field sec-

retary, he met with Amzie Moore, a veteran NAACP activist who had been

calling for a voting rights campaign since the late 1940s, and Bob Moses, a

twenty-five-year-old black teacher from Harlem who had befriended Moore

the previous summer. Meeting in Moore’s hometown of Cleveland, Missis-

sippi, in the heart of the Delta, the three men discussed the viability of estab-

lishing a pilot voting rights project in Cleveland and nearby Black Belt

communities. After assessing the local situation, they agreed that Cleveland

was not quite ready for an infusion of SNCC volunteers, but with Moore’s

help Sherrod and Moses soon found another site for the project in Pike

County, two hundred miles to the south. C. C. Bryant, the president of the

Pike County NAACP, shared Moore’s belief that voting rights held the key

to the liberation of black Mississippians. So when Bryant learned that SNCC

was interested in voter registration, he invited Moses and SNCC to McComb,