Arsenault Raymond. Freedom Riders: 1961 and the Struggle for Racial Justice

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

266 Freedom Riders

an exchange of drivers. A colorful character who sported dark glasses, a plaid

shirt, and a matching plaid-banded hat that made him look like he had just

come from the racetrack, Birdsong planned to lead the convoy all the way to

Jackson. However, after learning that a second and unexpected band of Free-

dom Riders had just left Montgomery, he peeled off from the caravan a few

miles outside of Meridian and headed back to the Alabama line.

4

Among the Freedom Riders themselves, the decision to send a second

group to Mississippi on Wednesday morning was a simple one in keeping

with CORE’s original plan to conduct bus desegregation tests on both major

carriers. But among officials in Montgomery, there was considerable sur-

prise when fifteen Freedom Riders purchased tickets for the late-morning

Greyhound run to Jackson. While rumors were rampant that hordes of Free-

dom Riders were descending upon the Deep South, the governmental ar-

rangements for the group that had congregated at Dr. Harris’s house had

assumed that the Wednesday morning Freedom Ride would involve only

one bus. The second group, like the first, included only one white Rider—

Peter Ackerberg, a student at Antioch College in Yellow Springs, Ohio—

and only two women: Lucretia Collins and Doris Castle. Six of the male

Riders—John Lewis, Rip Patton, John Lee Copeland, Grady Donald,

Clarence Thomas, and LeRoy Wright—were veterans of the Nashville Move-

ment, and three—Hank Thomas, John Moody, and Dion Diamond—were

Howard students and members of NAG. The remaining three Riders were

Frank Holloway, representing the Atlanta chapter of SNCC; Jerome Smith

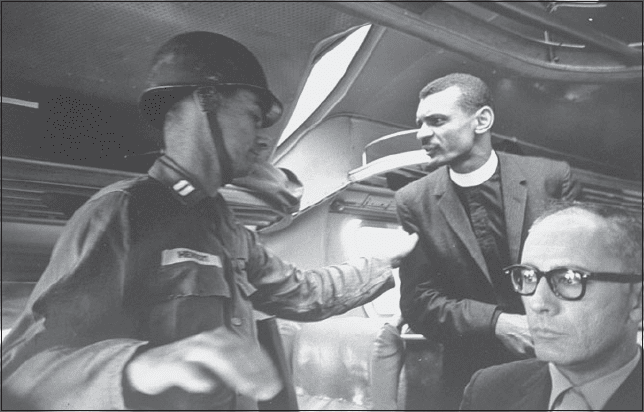

The Reverend C. T. Vivian pleads with Lt. Colonel Sonny Montgomery to make a

rest stop along the route to Jackson, Mississippi, Wednesday, May 24, 1961. The

man on the right is a news reporter. (Photograph by Lee Lockwood, Getty Photos)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 267

of New Orleans CORE; and Jim Farmer. Copeland was the oldest at age

forty-four, and Castle the youngest at eighteen.

The Greyhound group bypassed the most obvious choices and selected

Collins as their designated leader. Farmer, despite his prominence, was not

considered because no one was quite sure he actually intended to join the

Ride. Indeed, as he later acknowledged, he had no intention of going to Jack-

son until Castle shamed him into it. “I was frankly terrified with the knowl-

edge that the trip to Jackson might be the last trip any of us would ever take,”

he wrote in 1985. “I was not ready for that. Who, indeed, ever is? . . . It was

only the pleading eyes and words of the teenage Doris Castle that persuaded

me to get on that bus at the last minute.”

With Farmer finally on board, the bus left the terminal at 11:25 amid the

jeers of a crowd that had swelled to more than two thousand. Before the bus

pulled out, several National Guardsmen and reporters rushed forward to fill

some of the unoccupied seats near the Riders, as a much larger force of Guards-

men strained to control the crowd. Out on the highway, a hastily organized

escort of highway patrol cruisers and helicopters shadowed the bus’s west-

ward track, and the National Guardsmen along the route were once again

put on full alert. But, in general, the carefully arranged military procession

that had accompanied the first bus was missing. Though hardly on their own,

the Greyhound Riders knew nothing of the fate of the first bus and were

clearly more vulnerable to assault, or at least to feelings of insecurity, than

the Trailways Riders. “There was a lot of tension on the ride to Jackson,”

Collins recalled. “We didn’t know what would happen when we got to the

Mississippi line. Whether they were going to implement federal and Ala-

bama ‘state’ protection or turn us over to the Mississippi state police.”

When the bus reached the border and stopped for an exchange of drivers

and Guardsmen, a rumor of an impending ambush convinced all but one of

the reporters to travel the rest of the way by car. Mississippi officials waved

the bus onward anyway. Years later Farmer recalled the sight of Mississippi

Guardsmen flanking the highway with “rifles pointed toward the forests.”

To him the scene conjured up images of “runaway slaves a century ago, slosh-

ing through water and hiding behind trees as they fled pursuing hounds.

Visions of Harriet Tubman and the Underground Railroad. Visions, too, of

black bodies swinging, with bulging eyes and swollen tongues.”

To boost morale, and perhaps to calm her own fears, Collins conducted

an on-board workshop on nonviolence, and others sang freedom songs. But

there was no real antidote to the heart-stopping tension that Farmer claimed

was “greater than that felt by troops being dispatched to a battlefront where

bombs were bursting and comrades were dying.” That the Riders refused to

crack under the strain was, in Farmer’s words, a testament to their “indomi-

table human spirit.” As the bus rolled westward, Hank Thomas began sing-

ing a new version of the 1947 freedom song “Hallelujah! I’m a-Travelin’”

—creating an instant anthem by inserting the words “I’m taking a ride on the

268 Freedom Riders

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 269

Greyhound bus line, I’m-a-riding the front seat to Jackson this time.” By the

time the Greyhound pulled into the Jackson terminal, every Rider on the bus

was singing about traveling “down freedom’s main line,” convincing even

the most skeptical among them that somehow the journey to Mississippi would

turn out all right.

5

OFFICIALS IN MONTGOMERY AND WASHINGTON, not surprisingly, saw things

differently. From the perspective of those concerned about civil order and

national or regional image, the spirit that propelled the Riders onward looked

a lot like misguided fanaticism. For Robert Kennedy, in particular, the news

of a second bus inspired feelings of rage, betrayal, and even denial. The sup-

posed leaders of the Freedom Rider movement had said nothing about a

second bus, and Kennedy initially claimed that the Greyhound group had

“nothing to do with the Freedom Riders.” A few minutes later, when it be-

came clear to everyone that this was patently false, he issued a formal state-

ment praising the law enforcement efforts of Alabama and Mississippi

authorities and warning potential Freedom Riders that they would not be

accorded federal protection. No federal marshals had accompanied the Free-

dom Riders, he declared, and there were no plans to deploy marshals in the

future. After reiterating that “our obligation is to protect interstate travelers

and maintain law and order only when local authorities are unable or unwill-

ing to do so,” he claimed that “there is no basis at this time to assume that the

people of Mississippi will be lawless or that the responsible state and local

officials in Mississippi will not maintain law and order with respect to inter-

state travel.” Even so, he urged “all persons in Alabama and elsewhere to use

restraint and weigh their actions carefully.” For the good of the nation, he

insisted, the disruptive behavior by individuals and organizations on both sides

of the segregation controversy must be halted. “I think we should all keep in

mind,” he explained, “that the President is about to embark on a mission of

great importance. Whatever we do in the United States at this time which

brings or causes discredit on our country can be harmful to this mission.”

6

This appeal to Cold War patriotism would be repeated by Kennedy and

many others later in the day, but it came too late to have any effect on the

immediate situation in Alabama and Mississippi. By noon Kennedy’s hopes

for a quick resolution to the crisis had all but disappeared, and the reports

from the Deep South only got worse as the afternoon progressed. Five min-

utes after the second bus left the Montgomery terminal, a third group of

Freedom Riders departed from Atlanta. The leader of the group was Yale

University chaplain William Sloane Coffin Jr., a thirty-six-year-old graduate

of Union Theological Seminary who had served as a military liaison to the

Russian army during World War II and as a CIA operative during the Ko-

rean War. A nephew of the distinguished theologian Henry Sloane Coffin

and a member of the Peace Corps Advisory Council, the Reverend Coffin

represented the leftward-leaning wing of the Northeastern intellectual elite.

270 Freedom Riders

Prior to flying south, Coffin defended the Freedom Riders at a rally on

the New Haven green, arguing that “the time for moderation may be com-

ing to an end.” Later, in Atlanta, before boarding a Greyhound bus to Mont-

gomery, he and six other Riders held a press conference to announce their

intention to test facilities all along the route from Georgia to Louisiana. In

addition to Coffin, the group included three white professors of religion—

Gaylord Noyce of Yale, and David Swift and John Maguire of Wesleyan

University; a black Yale law student, George Smith; and two black students

from Johnson C. Smith University in Charlotte, North Carolina, Clyde Carter

and Charles Jones, both of whom had been active in SNCC and the Rock

Hill sit-ins. Coffin’s group would not arrive in Montgomery until mid-

afternoon, but their looming presence confirmed Kennedy’s fear that the

Freedom Rider movement was on the verge of enlisting a whole new crop of

well-meaning but misguided agitators. Although Georgia detectives were on

board the bus monitoring the situation, there was little anyone could do to

stop this latest challenge to civil order.

While Robert Kennedy and others were speculating about the implica-

tions of the Connecticut-based Freedom Ride, word came that the first bus

had reached Jackson. To Kennedy’s relief, the Freedom Riders had arrived

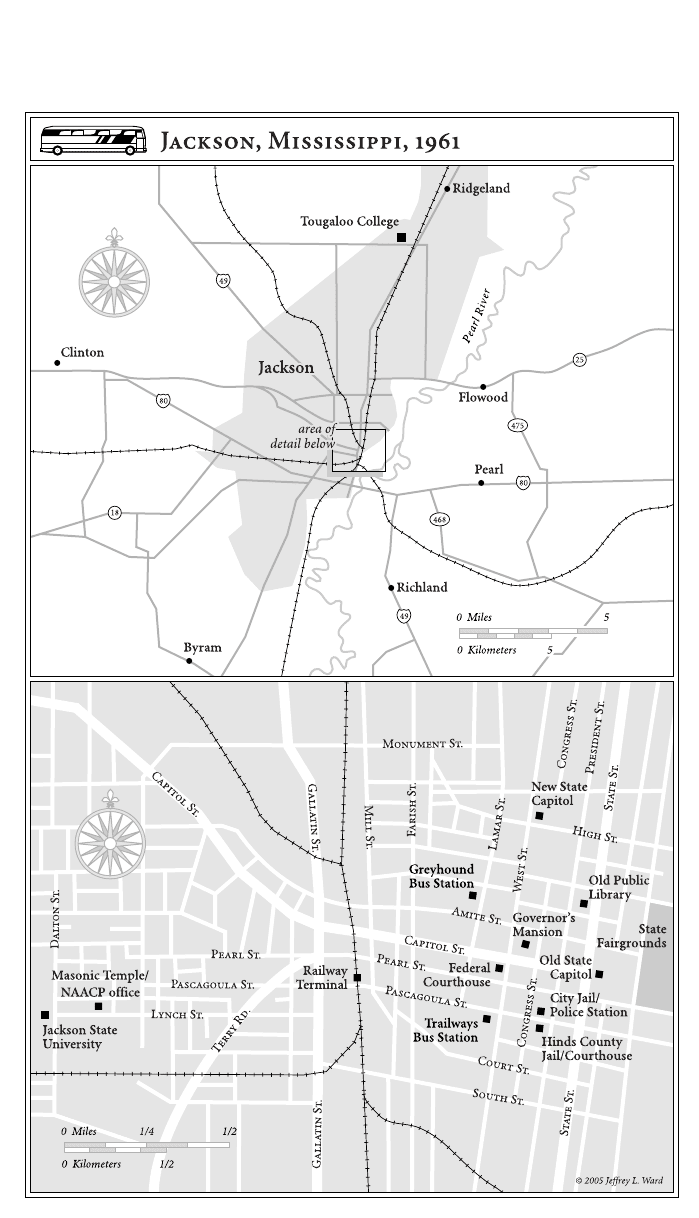

Yale University chaplain William Sloane Coffin Jr. (wearing glasses, walking to-

ward an armed National Guardsman) and six other Freedom Riders arrive at the

Montgomery Greyhound bus station, Wednesday afternoon, May 24, 1961.

Standing on the far left, partially hidden by the Guardsman, is Dr. David Swift.

Standing behind him nearest the bus, and wearing glasses, is Dr. John Maguire. The

three black Freedom Riders standing behind Coffin are (left to right) George Smith,

Charles Jones, and Clyde Carter. (Photograph by Perry Aycock, AP Wide World)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 271

safely a few minutes before two. But otherwise the news was not good. As

soon as the bus arrived at the Jackson Trailways terminal, the Riders, black

and white, filed into the white waiting room. Several also used the white

restroom, but when the Riders ignored police captain J. L. Ray’s order to

“move on,” all twelve were placed under arrest. As several reporters, a con-

tingent of National Guardsmen, and a small but cheering crowd of protest-

ers looked on, the police jammed the Riders into a paddy wagon and hauled

them off to the city jail. To make matters worse, Kennedy soon learned

that the arrested Riders had refused an offer by NAACP attorneys to post a

thousand-dollar bond for each defendant. The Riders would remain in jail at

least until their scheduled trial on Thursday afternoon. The formal charges

against the Riders were inciting to riot, breach of the peace, and failure to

obey a police officer, not violation of state or local segregation laws.

Later in the day the Jackson police dropped the riot incitement charge,

but that was cold comfort for federal officials who, despite fair warning from

Senator Eastland that the Freedom Riders would be arrested, had continued to

hope for an uninterrupted and uneventful journey to New Orleans. In a 1964

interview, Robert Kennedy reluctantly acknowledged his complicity, conced-

ing that he had, in effect, “concurred to the fact that they were going to be

arrested.” Eastland, he recalled, had told him “what was going to happen:

that they’d get there, they’d be protected, and then they’d be locked up.” But

for some reason the near certainty of the arrests escaped him and others in

May 1961.

While the Trailways Riders were settling in at the Jackson city jail, ru-

mors of an impending invasion from the east were precipitating a volatile

situation at the downtown Montgomery Greyhound terminal. By the time

Coffin’s group arrived, a crowd of unruly protesters—some of whom had

been at the scene since early morning—was ready for a fight. As Wyatt Tee

Walker and Fred Shuttlesworth stepped forward to welcome the seven new

recruits, the crowd began pelting them with rocks and bottles. For twenty

minutes a cordon of National Guardsmen strained to keep the protesters at

bay, as officials puzzled over how to get the nine civil rights activists out of

harm’s way. Fortunately, the siege was broken when the Guardsmen cleared

a path through the crowd large enough to accommodate two cars, one of

which was driven by Ralph Abernathy. With the Guardsmen holding back

the crowd, the grateful Riders and their hosts climbed into the cars, though

it took a minute or two to find a safe exit. In the meantime, several reporters

approached the cars to get a statement from Abernathy. Asked what he thought

about Robert Kennedy’s complaint that the Freedom Riders were embar-

rassing the nation in front of the world, Abernathy responded tartly: “Well,

doesn’t the Attorney General know we’ve been embarrassed all our lives?”

7

What the attorney general knew, or did not know, about black life would

ultimately have a profound bearing on the evolution of the Freedom Rider

crisis. But on the afternoon of May 24—in Washington no less than in

272 Freedom Riders

Montgomery and Jackson—pure emotion seemed to be driving much of

the official reaction to the Freedom Riders’ exasperating commitment to

nonviolent direct action. Although Robert Kennedy was angry at Ross Barnett

for allowing the Jackson police to put the Trailways group in jail, he was

even angrier at the obstinacy of the Riders themselves. Mostly he was wor-

ried about the apparent widening of the crisis, and he said so in blunt terms

in a late afternoon press release. In a thinly veiled reference to Coffin’s group

and others contemplating the mobilization of Northern sympathizers, he

condemned “curiosity seekers, publicity seekers, and others who are seeking

to serve their own causes.” Considering the “confused situation” in Alabama

and Mississippi, travel in these states was inadvisable, according to Kennedy.

Indeed, he had received word that a bomb threat had forced the evacuation

of the Montgomery Greyhound terminal just minutes after Abernathy and

Coffin’s group had driven away. Making a public plea for “a cooling-off pe-

riod,” he claimed that “it would be wise for those traveling through these

two states to delay their trips until the present state of confusion and danger

has passed and an atmosphere of reason and normalcy has been restored.”

Otherwise, he suggested, “innocent people may be injured,” adding: “A mob

asks no questions.”

Judging by the earlier rejection of his private plea for a cooling-off pe-

riod, Kennedy knew that movement leaders, not to mention the Freedom

Riders themselves, were unlikely to respond favorably to his request for what

amounted to a moratorium on activism. Indeed, he was disappointed but not

surprised when one of the first responses, a telegram from the Reverend

Uriah J. Fields, representing the Montgomery Improvement Association,

chastised him for ignoring a century of delayed justice. “Had there not been

a cooling-off period following the Civil War,” Fields insisted, “the Negro

would be free today. Isn’t 99 years long enough to cool off, Mr. Attorney

General?” Nevertheless, with the crisis deepening, Kennedy felt that he had

little choice but to put the Freedom Riders on the moral defensive. If they

were unwilling to listen to reason, they would have to suffer the consequences

of abandoning the sensible restraint of Cold War liberalism. While he had

considerable and rising sympathy for their goals, he could not understand

their stubborn adherence to a means of protest that put themselves and the

nation at risk. With nothing less than the national image at stake, he had few

if any qualms about pointing out their lack of patriotism. And he was hardly

the only one who felt that way. Speaking on NBC television’s evening news

broadcast, commentator David Brinkley, a native of North Carolina, editori-

alized that the Freedom Riders “are accomplishing nothing whatsoever and,

on the contrary, are doing positive harm.” While acknowledging that the

“bus riders are, of course, within their legal rights in riding buses where they

like,” he maintained that “the result of these expeditions are of no benefit to

anyone, white or Negro, the North or the South, nor the United States in

general. We think they should stop it.”

8

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 273

Robert Kennedy was heartened by Brinkley’s commentary, and the sub-

sequent arrest of the second group of Freedom Riders following their late-

afternoon arrival in Jackson only reinforced his willingness to sacrifice

immediate justice in the interests of national security. The second round of

arrests followed the same pattern as the first, with the Jackson police swoop-

ing in and apprehending all fifteen Riders within three minutes of their ar-

rival. As Farmer recalled the scene: “As soon as we walked out of the door,

they [the Jackson police] parted, and they knew precisely where I was going,

to the white waiting room and not to the colored waiting room. So they

parted and made a path for me leading right to the white waiting room [laugh-

ing], and I thought maybe I could have pled entrapment when we got to

court, because we couldn’t go anyplace else.” Walking behind Farmer, Lewis

had just enough time to make it to the white men’s room, where he was

unceremoniously arrested while standing at a urinal. When the arresting of-

ficer told him to move, Lewis said: “Just a minute. Can’t you see what I’m

doing?” That only angered the officer, who barked: “I said move! Now!”

Kennedy was unaware of this and other indignities until much later, but

his mood was such that only a full-scale beating, which the Jackson police

were careful to avoid, would have garnered any sympathy. His patience with

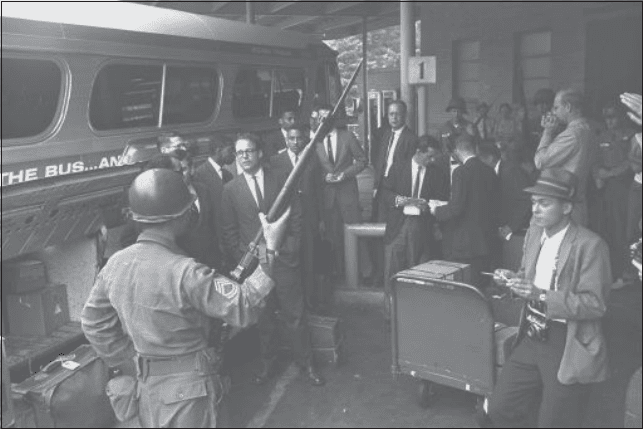

The Greyhound group of Freedom Riders arrives in downtown Jackson,

Mississippi, where local policemen and police dogs stand guard, Wednesday

afternoon, May 24, 1961. (Library of Congress)

274 Freedom Riders

the Freedom Riders was growing thin, especially after he learned that the

second group, like the first, had refused bail and was even talking about re-

maining in jail following their expected convictions on Friday. On the way to

jail, they had serenaded the paddy wagon driver with chorus after chorus of

“We Shall Overcome,” which included the line “We are not afraid”; and

they seemed to mean it. If Kennedy had thought that having the Freedom

Riders in jail would put an end to the crisis, he would have been all for it. But

he knew better, realizing that in the upside-down world of movement cul-

ture the incarceration of twenty-seven activists would only encourage others

to put their bodies on the line. While he admired their courage, he ques-

tioned their sanity. He could only hope that a few hours in a Mississippi jail

cell would change their minds. To this end, he asked Marshall and White to

see if any of the jailed Riders would reconsider the decision to remain behind

bars. When they could not find anyone willing to discuss the matter, much

less agree to an early release, Kennedy decided to call King directly to see if

he could be persuaded to intervene on behalf of a more reasonable approach

to nonviolent protest.

The resultant exchange between the two young leaders did not go well.

Transcribed by Kennedy’s aides, the conversation testified to the wide ideo-

logical gap between nonviolent activists and federal officials—even those who

had considerable sympathy for the cause of civil rights:

King: It’s a matter of conscience and morality. They must use their lives

and bodies to right a wrong. Our conscience tells us that the law

is wrong and we must resist, but we have a moral obligation to

accept the penalty.

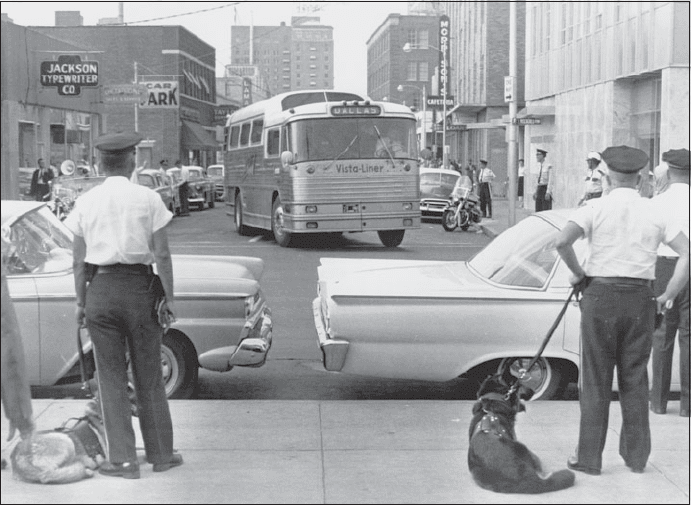

Jim Farmer leads a

group of Freedom Rid-

ers into the white wait-

ing room at the Jackson

Greyhound bus station,

Wednesday afternoon,

May 24, 1961. The

Freedom Rider walking

behind Farmer is Frank

Holloway. The man

wearing a hat and

standing in front of the

bus is T. B. Birdsong,

head of the Mississippi

Highway Patrol. (Pho-

tograph by Lee Lock-

wood, Getty Photos)

Freedom’s Coming and It Won’t Be Long 275

Kennedy: That is not going to have the slightest effect on what the govern-

ment is going to do in this field or any other. The fact that they

stay in jail is not going to have the slightest effect on me.

King: Perhaps it would help if students came down here by the hundreds—

by the hundreds of thousands.

Kennedy: The country belongs to you as much as to me. You can determine

what’s best just as well as I can, but don’t make statements that

sound like a threat. That’s not the way to deal with us. [a pause]

King: It’s difficult to understand the position of oppressed people. Ours

is a way out—creative, moral and nonviolent. It is not tied to black

supremacy or Communism, but to the plight of the oppressed. It

can save the soul of America. You must understand that we’ve

made no gains without pressure and I hope that pressure will al-

ways be moral, legal and peaceful.

Kennedy: But the problem won’t be settled in Jackson, but by strong federal

action.

King: I’m deeply appreciative of what the Administration is doing. I see

a ray of hope, but I am different from my father. I feel the need of

being free now.

Kennedy: Well, it all depends on what you and the people in jail decide. If

they want to get out, we can get them out.

King: They’ll stay.

9

Despite King’s strained attempt to salvage the conversation, the call left

both men shaken and angry. After hanging up, King complained to Coffin

and others who had gathered in Abernathy’s living room: “You know, they

don’t understand the social revolution going on in the world, and therefore

they don’t understand what we’re doing.” Kennedy, meanwhile, feeling that

he knew all too well what was going in Montgomery and Jackson, immedi-

ately called Harris Wofford, the only administration official with close ties

to the nonviolent movement. “This is too much,” an exasperated Kennedy

told Wofford. “I wonder whether they have the best interest of their country

at heart. Do you know that one of them is against the atom bomb—yes, he

even picketed against it in jail. The President is going abroad and this is all

embarrassing him.”

Back at Abernathy’s house, the postmortem on the Kennedy call was

evolving into a long and wrenching discussion of whether the group should

go on to Jackson in the morning. Stung by the suggestion that joining a

Freedom Ride was unpatriotic, Coffin and the others asked King for guid-

ance. Should they go on in the face of Kennedy’s plea for a moratorium?

King answered the question by leading them in prayer, after which a vote

was taken by secret ballot. Despite considerable anguish, the vote was unani-

mous. All agreed that they had come too far to turn back, and one of the most

adamant was John Maguire, a Montgomery native who had been shocked by