Anderson J.M. Daily Life during the French Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

130 Daily Life during the French Revolution

their clothes taken to be washed and rid of fl eas, while the patient was

examined by a student surgeon to ascertain if the illness was genuine and

that the patient was not suffering from any of the diseases that were barred

from the institution. If all was in order, the patient received a kind of uni-

form from the nursing sister and was then sent to the hospital chaplain

for confession. Finally, the patient was ushered to a bed.

6

With thousands

of dying old men and old women, babies, orphans, and handicapped and

deformed people, the hospitals gave an impression of a scene from hell.

By 1789, Paris was being cleaned up, and in the process the establish-

ment began to realize that mortality in cities was greater than that in the

country because the urban environment was so deleterious for its inhabit-

ants. Doctors agreed that a serious health risk was present because people

were forced to breathe air infected with the odor of bodies decaying in the

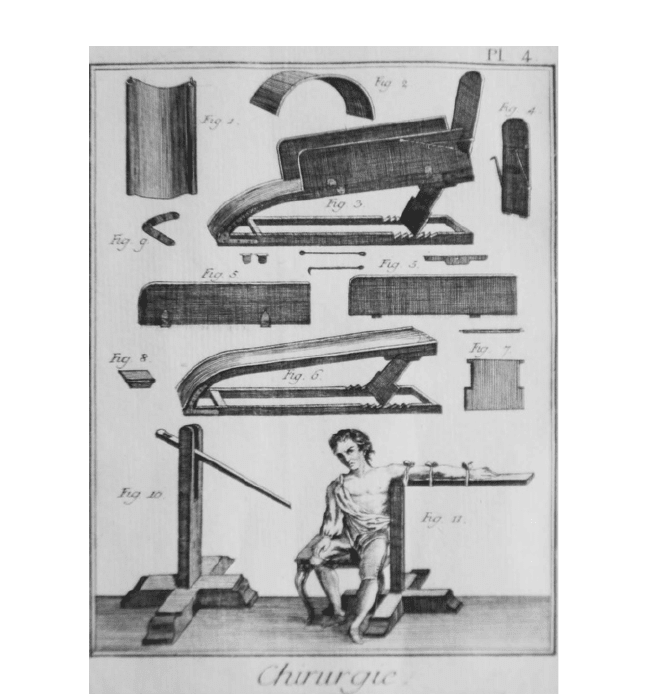

Surgical supports ca. 1770, including arm restraints and an

adjustable reclining seat, with diagrams of its various parts.

Health, Medicine, and Charity 131

cemeteries, where they were often not properly buried, and by the open

sewers in the streets. Many houses still had chamber pots for toilets, and

these were emptied into the streets at night, giving the neighborhood an

insalubrious and disagreeable ambiance.

New graveyards were created outside the walls of the city, but this met

with opposition from those who wanted their loved ones buried close by,

and, in the end, burials continued in town for some time to come.

During the late eighteenth century, proper nourishing food began to be

a subject of discussion, along with the quality of the air. At least for the

wealthy, wholesome food and clean air were becoming priorities. Concern

was also expressed over the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris, whose humid and airless

interior gave rise to perpetual pestilence.

7

Enlightened campaigns advo-

cated opening windows both in hospitals and in private homes to let fresh

air circulate.

Preoccupation with cleanliness within the city slowly began to extend

to concern for the cleanliness of the body; doctors started encouraging

people to wash themselves more frequently. Up to this time, little or no

attention had been paid to washing even excrement off the body.

Since the nuns were also in the business of making good Christians out of

the patients, many hospitals had chapels of their own or altars in the rooms.

Salaried priests kept track of death records and led the sick in prayer, helped

draw up wills, buried the dead, administered the sacraments, catechized

children, confessed new entrants, and said Masses for benefactors. Sisters

also watched over the patients at mealtimes to ensure that there was no

traffi cking in food, no blasphemy, boasting, or inappropriate conversa-

tion that refl ected poorly on the hospital and the Catholic religion. Sisters

could impose rebukes and mild punishments, such as reducing rations

or short imprisonment. Serious matters of insubordination or discipline

were taken up by the administration board, and retribution could include

corporal punishment or banishment from the hospital.

Up to the middle of the eighteenth century, if a patient under a doctor’s

care died (as frequently happened), the cause was put down to God’s will.

Once the doctors were put in charge, however, they increasingly saw dis-

ease as part of nature, unrelated to sin and God, and insisted on a secular

medical program set apart from the spiritual explanations of the church.

QUACKS AND CHARLATANS

The common people, superstitious and with a faith in panaceas, were

often beguiled by medical charlatans. The elixirs these itinerant vendors

offered might have been made of harmless vegetable juices and herbs, but

all were touted as a cure for most ailments.

Peddlers gathered crowds on street corners, extolling the virtues of

their product. Some, to attract people’s attention, supplied entertainment:

132 Daily Life during the French Revolution

acrobats, jugglers, fi rework displays, dancers, musicians, and tightrope

walkers beckoned the curious. Markets, festivals, and fairs drew the dis-

sembling healer to put on his show and sell his concoctions. In one case,

Alexandre Cosne, son of a Parisian building worker, appeared with a huge

pool complete with mermaid, who answered questions from the crowd.

Cosne would turn up in cities claiming to be a magical healer whose potion

would cure eye ailments, skin disease, stomach problems, halitosis, and

syphilis. It was also touted as particularly effective for dyeing hair!

8

In Paris, the Pont Neuf, which spans the river Seine, was a primary

gathering point for swindlers, thieves, beggars, entertainers, and other

sundry people. Here there was someone to pull a rotten tooth, make eye-

glasses, or fi t an ex-soldier with a wooden leg. There were those who sold

powdered gems guaranteed to beautify the face, drive away wrinkles, and

add to longevity.

MIDWIVES

An integral component in the lives of the French were the midwives

who assisted in the delivery of children. They generally lacked any for-

mal education, especially in rural areas, but as good Catholics they could

be relied on by the state and the church under the old regime to record

the births and to report those to unmarried mothers. Midwives were

usually middle-aged and often widowed women who used their skills in

childbirth to help make ends meet by charging a small fee. In the 1780s,

they began to receive a little technical training at state expense in a num-

ber of dioceses, and they could receive a diploma of competence from

their local guild of surgeons after a six-month course at the Hospice de la

Maternité in Paris. Few attended these classes, however. After the revo-

lution, the government attempted to extend its control over midwives

when the medical establishment complained that they were very ignorant

and illiterate and in many cases did not understand the French language.

Government agents weeded out the most incompetent but realized that to

ban all who were unqualifi ed would essentially eliminate their function.

Those who had won the confi dence of local inhabitants were allowed to

carry on.

BABIES AND WET-NURSES

Special care was taken of abandoned children, the future hope of the rev-

olution. These enfants trouvés (foundlings) increased in number as the wars

took many fathers. Government grants were dispersed to operate the found-

ling centers, but soon funds dried up and the children’s living situations

reverted to the terrible conditions that had prevailed before the revolution,

with a 2 or 3 percent survival rate.

Health, Medicine, and Charity 133

There was generally no shortage of babies and children in the medical

institutions. Foundling children abandoned on the steps added to the

inventory of unwanted infants brought in by the parents and of orphans.

Overcrowded conditions were generally the rule. After spending a little

time in a children’s ward, where the majority died while waiting for

arrangements to be made, the surviving infants usually spent their early

years of life with a wet-nurse.

Wet nursing was common in villages, especially those close to large

towns, from which thousands of babies of all classes were sent each year

to foster mothers who performed the service of breastfeeding. Even poor

working mothers sometimes put a child born out of wedlock into the

hands of a wet-nurse, maintaining contact with it if it survived. The trade

was regulated, and, at a special offi ce in Paris, police kept dossiers on

women engaged in this business, supervising the agents whose job it was

to connect the mothers with the nurses. The government feared a drop in

population, and breastfeeding was felt to be the natural and healthy way

to nourish a baby.

Montpellier’s General Hospital and that of Nîmes recruited women

in the impoverished villages of the Cévennes and paid them about four

livres a month to act as wet-nurses. Local wet-nurses were generally not

available since they could make more money from private families; but

the destitute women of the mountain villages were willing to take their

chances with contracting venereal diseases, which were sometimes car-

ried by foundlings.

9

On occasion, the women would lie about their ability

to feed the babies, instead feeding them animal milk or water with boiled,

old, and even moldy bread in it. The journey to distribute the babies from

the hospitals to the villages, a distance of more than 60 miles, was slow

and diffi cult. The children were placed four at a time into a basket stuffed

with straw and cushions and hitched to a mule for the miserable ride to

the Cévennes. Forty percent of those who reached their destination alive

died within the fi rst three months, and more than 70 percent died within

the fi rst year.

10

Many deaths were caused by malnutrition, neglect, and

dysentery. Those sent to the villages often sat in animal and human excre-

ment, their mouths stuffed with rotting rags, or were slung from the rafters

in makeshift hammocks, their swaddling clothes seldom changed. Similar

baby-farming was carried out in other major cities, including Paris, and

often the agents failed to report the death of a child to the authorities,

pocketing the money for the child’s nurse instead.

11

At fi ve, the children returned to the hospital (although in a few cases

they were adopted by the wet-nurse). Here they continued to be exposed

to unhealthy conditions, and, again, survival was at stake. For those who

managed to grow to adulthood, attempts were made to integrate them

into society, but all carried the melancholy scars of their past; most were

sickly and tended to become misfi ts in society at large.

134 Daily Life during the French Revolution

CHARITY AND THE WELFARE STATE

One of the most serious problems in eighteenth-century France was

poverty. The poor and sick, the crippled, the old, the widows, the orphans—

all were of concern and were eligible for charity. Relief was administered

through the Catholic Church, and, although it did little more than pre-

serve the poor and affl icted at the most elemental level of existence, this

aid saved lives. Parish priests, as well as cathedral chapters and abbeys,

took on the role of distributing funds that came from donors abiding by

their religious obligation to give alms.

The desperate fi nancial problems of the 1780s reduced royal patronage

for the poor. The number of destitute people reached staggering propor-

tions, and their suffering rose to unprecedented levels, with about one in

fi ve people poverty-stricken.

Besides the sisters of various Catholic organizations, many women

were dedicated to charity. They lived mostly in small towns or villages

and were often widows, spinsters, or young single ladies. Most were of

modest means, but they saw charity as a way of enhancing the social life

of the town. Sometimes they gave their time to help the illiterate learn to

read or gave a few coins regularly to a destitute family. The abolition of

the dîme or church tithes curtailed the ability of the church to administer

charity to the poor.

The revolutionaries explored the issues and extent of charity and

poverty through the Comité de Mendicité (Committee for Charity), hoping

to fi nd solutions that would benefi t the recipients. They stressed the

role of the state in combating this blight on the nation. As under the old

regime, the poor were feared because they lived outside the established

modes of society, often begging or involved in crime. Nevertheless, it was

agreed that one function of the state was to help those who could not help

themselves. Old age, sickness, the premature death of the family bread-

winner, injury, and unemployment—all were common reasons for being

poor. Vagaries of climate and weather conditions, fi res or fl ooding that

destroyed crops, or outbreaks of disease could reduce entire towns and

countryside to a state of virtual starvation.

In the early years of the revolution, poor relief was no longer considered

a form of charity; the right to receive necessary assistance was seen as a

basic human right. Every man had the right to feed and clothe himself

and his family. Relief was to be paid for by taxation, which went to hospi-

tals, state pensions, public work projects for the unemployed, and care for

abandoned children.

The government was heading toward a welfare state from about 1789

to 1795. The reports of the Comité de Mendicité were thorough, and the

results indicated that the old regime and the church had failed to give

aid to the poor when and where it was needed. The committee believed

that poverty could be alleviated only by concentrating all relief efforts in a

Health, Medicine, and Charity 135

centralized state authority. Only then could a rational program be devised

and better administered, on the basis of population densities and fairly

assessed taxes. It was felt that every community should have a charity

offi ce to provide home relief for the aged and the ill. Workshops would

also be made available for those who were able-bodied but unemployed.

Prisons were to be established for those beggars who refused state relief

measures.

12

It was also suggested the property of the church be split up

in small lots and distributed to the poor, since property and employment

were the best safeguards against increasing poverty. The committee rec-

ommended that hospitals (badly administered, secretive, unhygienic

money-wasters) be restricted to taking care of orphans and foundlings

waiting for foster homes and the homeless aged. The sick could be better

cared for at home.

The Comité de Mendicité proposed that able-bodied men receive relief

only in return for labor; the infi rm would receive free food and money

fi nanced by the government. State work schemes were arduous, the tasks

often menial, and unwilling workers were sent to 1 of the 34 poorhouses,

called Dépôts de Mendicité. The plan to register everyone needing help

failed. High prices, the rapidly declining assignat, price controls during

the Terror, industrial stagnation, the costs of the revolutionary wars—all

conspired to thwart the plans of the government.

State workshops to alleviate unemployment were introduced in 1790

but were not well received by the general public and were discontinued

by the Directory. The proposals that might have created a welfare state

and lifted the nation out of poverty were soon in full retreat as the govern-

ment, lacking the money, experience, and bureaucracy needed to match

the ideals with the practice, reneged on its relief efforts and rejected fi nan-

cial responsibility for the poor.

The beginning of the nineteenth century brought the recovery of poor-

relief institutions, which in part owed their salvation to the rehabilitation

of the Catholic Church under Napoleon.

REPORTS OF ENGLISH TRAVELERS

In the eighteenth century, charitable institutions, prisons, and hospitals

were as much on the agenda of tourists as Nôtre Dame and the Tuileries

gardens.

13

Some English travelers reported their observations. On the

whole, the institutions in the provinces seemed more humane and less

offensive than those in Paris.

Harry Peckham, a barrister, traveled in France and published an account

of his tour in 1772. In it, he states:

the whole kingdom swarms with beggars, an evidence of poverty, as well as defect

in the laws. The observation was confi rmed at every inn I came to, by crowds

of wretches, whose whole appearance spoke of their misery. I have often passed

136 Daily Life during the French Revolution

from the inn door to my chaise through a fi le of twenty or thirty of them; even the

churches are infested with them.

George Smollett visited the Hôpital des Enfants Trouvés and remarked:

When I fi rst saw the infants at the enfants trouvés in Paris, so swathed with bandages,

that the very sight of them made my eyes water. . . .

Thomas Pennant left his account of a visit, stating that nearly 6,000

foundlings were admitted annually and taken care of by the nuns, the

Filles de Charité. “Their names &ca are kept in a little linnen purse and

pinned to their Caps that their parents may know them if inclined to take

them.” It is not clear how the sisters would know their names if they had

been abandoned on the steps of a church or left in a ditch.

In October 1775, Mrs. Thrale and her companion, Admiral John Jervis,

visited a hospital as part of their sightseeing tour, and she described it as

“cleaner than any I have seen in France.” She also wrote, “and the poor

Infants at least die peaceably cleanly and in Bed—I saw whole Rows of

swathed Babies pining away to perfect Skeletons, & expiring in very neat

Cribs with each a Bottle hung on its Neck fi lled with some Milk Mess,

which if they can suck they may live, & if they cannot they must die.”

In 1776, Mrs. Montagu reported that she saw about 200 infants in their

little beds, none above seven or eight days old: “if some had not cried I

should have taken them for dolls. After keeping them at most 8 days they

are sent to be nursed in the country.”

The Hôtel-Dieu in Paris also attracted many travelers and foreign doc-

tors who have left various comments. Thicknesse wrote that the hospital

was a noble charity and worthy of the name if it was well regulated:

But alas! it is no uncommon thing to see four, fi ve, six, nay sometimes eight sick

persons in one bed, heads and tails, ill of different disorders, some dying, some

actually dead. Last winter a gentleman informed me that he heard one of the

patients there complain bitterly of the cold, and particularly of that which he felt

from the dead corpse which lay next to him in the bed!

Dr. James St. John, a London practitioner, was appalled by what he

saw at the Hôtel-Die u, commenting (besides remarking on the number of

patients in one bed):

The corrupt air and effl uvia in some parts of the hospital are more loathsome and

abominable than can be conceived. It is amazing, that there are men of constitu-

tions suffi ciently vigorous, to recover in such a place of vermin, fi lth, and horror.

Other visitors and writers of the period reported similar conditions.

Adam Walker, a science lecturer, who was there in 1785, remarked on

Health, Medicine, and Charity 137

the size of the hospital as larger than any in London and on the number

of patients as more than would be found in all the hospitals in London,

adding:

It seems an assemblage of all human miseries! … In one bed … you may see two

or three wretches in all the stages of approach to death!

He goes on to describe more favorable features—clean, high-ceilinged

rooms and constant ventilation.

The following year, the Reverend Townsend confi rmed seeing many

patients in one bed but stated that “The practice of stowing so many mis-

erable creatures in one bed is to be abolished.”

Edward Rigby, who practiced medicine in England, was in Paris in

1789 and found the hospital that he visited in July to be “very dirty and

crowded, containing 8,000 patients.”

Visitors went to other hospitals in and around the capital, such as the

Hôpital Général, established primarily to meet the problem of poverty,

and two other multipurpose establishments—the Salpêtrière and Bicêtre.

Pennant recorded his visit:

Went to the Hospital de Salpetriere, a little way out of Paris, a sort of workhouse

for girls and women, of which there are in the house 7500. I saw 400 at work in

one room: 500 in another. They embroider, make lace and shirts, and weave coarse

linen, also cloth; all which is sold for the benefi t of the hospital. . . . It is also an Asy-

lum to such poor families whose head is dead, or has deserted them; in short, it is

the asylum of the miserable, tho’ each is obliged to work to support the whole.

Bicêtr e, an even larger hospital, was farther from the center of Paris

and had fewer curious visitors. According to Dr. John Andrews, it was

a place for “defrauders, cheats, pickpockets … convicts for petty larceny

… vagrants, idlers, mendicants.” He went on to speak of the mentally ill

and the unemployed. Discipline was severe. Andrews considered Bicêtre

a humane and useful institution, but opinions differed. In the autumn of

1788, Sir Samuel Romilly, a lawyer and reformer, traveled to Paris and

visited the hospital in the company of others, including the antiroyalist

Mirabeau. Both were horrifi ed at what they saw.

Romilly followed Mirabeau’s suggestion that he write down what he

had seen, and Mirabeau later translated his notes into French and had

them published. The publication was suppressed by the police, but

Romilly published the English text in London. The tenor of the essay was

expressed in the fi rst paragraph:

I knew, indeed, as every one does, that it [ Bicêtre ] consisted of an hospital and a

prison, but I did not know that, at Bicêtre an hospital means a place calculated to

generate disease and a prison, a nursery of crime.

138 Daily Life during the French Revolution

There were boys under the age of 12 incarcerated there, and men who

were often kept for years in underground dungeons. In the common room

were boys and men who had simply argued with or insulted the police on

the streets of Paris. Every vice was practiced; the author fel1t obliged to

describe these in Latin.

DENTISTS

Joseph Daniel, who called himself a surgeon dentist, fi tted crowns of

a new design that would function like natural teeth. He claimed that

they would always keep their color.

14

One of his advertisements read as

follows:

DENTAL SURGEON

M. Daniel, dental surgeon, Fossés-St. Germain l’Auxerrois Street, no. 15, has

acquired, by long experience, much dexterity in removing the most diffi cult teeth

and roots when they cannot be preserved. He cleans, whitens and dries them and

destroys the nerve, fi lls them successfully, takes out **geminates, puts back the

good ones and inserts artifi cial teeth, **on spring-loaded posts of a new invention,

stable and unbreakable. He has also discovered a metallic thread for teeth and

false teeth much cheaper than gold. He blends a toothpaste for tooth and gum

care; 3 livres and 6 livres per jar.

CP—13 April 1792

In addition to cleaning and extracting teeth, dental practitioners sold a

variety of painkillers. They were also interested in the repair of decayed

teeth and the replacement of lost ones. By the 1790s, complex restorative

and prosthetic techniques and specialist dental practice was well estab-

lished.

15

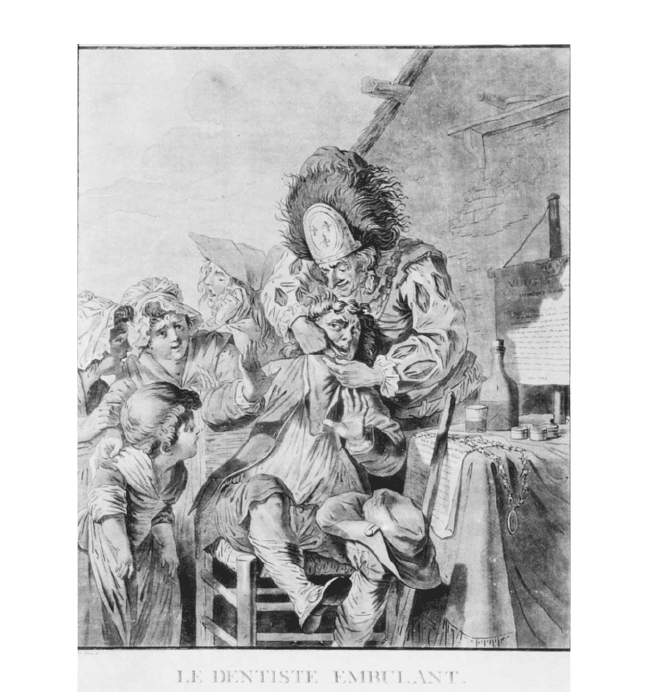

To have a tooth extracted, the patient was normally seated in a low chair

or on the ground, while the dentist stood over him, tongs in hand. As

the patient held on to the dentist’s legs for support, the toothpuller could

certainly tell how much pain he was causing by the intensity of the grasp,

but conducting the procedure in this manner benefi ted the dentist, for it

allowed him to get a good grip on the tooth and jerk it out.

One of the most fl amboyant mid-eighteenth-century tooth extractors was

a huge man called Le Grand Thomas, who could usually be found on the

Pont Neuf in Paris. Accompanied by his magnifi cent horse, adorned with

an immense number of teeth strung like pearls around its neck, assistants

would examine the teeth of any willing passerby to see what might need

to come out. Thomas stood by in his hat of solid silver, which balanced a

globe on top and a cockerel above that. His scarlet coat was ornamented

with teeth, jawbones, and shiny stones, a dazzling breastplate represented

the sun, and his heavy saber was six feet long. A drummer, a trumpet

Health, Medicine, and Charity 139

player, and a standard-bearer made up the balance of his retinue. Grand

Thomas did not live to see the revolution, but there were thousands of

such rogues around the country who seem to have had little trouble fi nd-

ing patients. Most people of the time neglected their teeth until something

drastic had to be done. Only the rich could afford a qualifi ed dentist.

By 1768, to become a dentist, a practitioner was obliged to present himself

for examination by the community of surgeons of the town in which he

wished to practice and to have previously served either two complete and

consecutive years’ apprenticeship with a master surgeon or an expert who

was established in or around Paris or three years’ apprenticeship with sev-

eral master surgeons or experts in other towns. Dentists in Paris and other

large cities were trained at the Collège Royal de Chirurgie (Royal College of

Surgery), which opened in 1776. They had to pass examinations in both

The itinerant dentist, his patient, and interested onlookers.

National Institute of Medicine.