Anderson J.M. Daily Life during the French Revolution

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

120 Daily Life during the French Revolution

take fencing, riding, or dancing lessons, join a lending library, or attend

town-sponsored events or even a public séance at the local academy of

arts and sciences. Those old enough could enroll in the rapidly spread-

ing order of Freemasonry. Both secular and theology students amply

employed the services of prostitutes.

Since most students were studying theology or law, science education

was provided primarily for future candidates for the upper levels of the

church and the bar. During the course of the century, the number of those

interested in medicine grew, but even on the eve of the revolution, they

formed fewer than 10 percent of the total number of students. There were

relatively few doctors in the cities of France at this time compared to the

number of lawyers, judges, canons, and curates. Near the end of the cen-

tury, the town of Angers, with a population of 27,000, recorded a dozen

physicians but 70 canons and 17 curates.

22

Medical students in Paris usually attended the Jardin du Roi and the

Collège Royal. On the national stage, only three universities were notable

for medicine—Paris, Montpellier, and Toulouse.

Professors within the colleges or universities took care not to let new

ideas disturb the established prejudices and order. The thoughts of the

eighteenth-century philosophers, who worked and created their ideas out-

side the universities, were generally dismissed. The teaching profession’s

support for the monarchy and professors’ espousal of the concept of the

divine right of kings predisposed many of their students to become sup-

porters of absolutism. Higher education thus played a role in preserving

such ideals. In addition, professors were unwilling to remove God from

their views and theories .

23

By the beginning of the revolution, study of the

humanities generally remained unrewarding, as teachers did little more

than provide the same old commentaries on the same old texts they had

been using for years. New philosophical ideas were considered a nuisance

to be ignored if at all possible. In 1789, the sciences, physics, and medicine

were advancing from simple explanation to a more empirical approach

but offered no threat to church or state.

Once the revolutionary government was in place, control

of schools and education was transferred from the church

to the state, whose proclaimed goals were the promotion

of intelligence, morality, and patriotism. On May 4, 1793,

Condorcet, the chairman of the Public Instruction Committee, renewed

an earlier proposal that claimed that the nation had the right to bring up

its children and could not concede this trust solely to families and their

individual prejudices. Education was now to be common and equal for all

the people. Thus, indoctrination by the Catholic Church was replaced by

indoctrination by the state, with nationalism becoming the religion.

In the same year, the Convention ordained that no ecclesiastic could

teach in state-run schools, which henceforth would be free of charge, with

attendance compulsory for all boys. Girls were to have private governesses

State

Education

Family, Food, and Education 121

or tutors if the family could afford it. This practice was taken up primarily

by the bourgeoisie and might consist of instruction in music (piano), art,

reading, and reciting of the classics; otherwise, girls had to rely on their

mothers for instruction in needlework, care of the household, and the art

of being a good wife and mother. The revolutionary government always

kept in mind young men and the particular concern that their education

prepare them for future roles in the new society.

Sometimes the application of theories bordered on the absurd: consider

the following dialogue in which the mother of a patriot family takes it

upon herself to infl ict upon her young child the questionnaire included by

Citizenness Desmarest in her Elements of Republican Instruction.

“Who are you?”

“I am a child of the Patrie. ”

“What are your riches?”

“Liberty and equality.”

“What do you bring to society?”

“A heart that loves my country and arms to defend it with.”

24

For most members of the Convention, a new regime required a new

kind of education. Robespierre and Saint-Just were obsessed by this idea,

maintaining that, as a citizen, the child belonged to the state, and commu-

nal instruction was essential. Until the age of fi ve, they were their mother’s

concern (but only if she clothed and fed them). After that, they belonged

to the republic until their death. Pupils were to sleep on mats, dress in

linen in all seasons and weathers, and eat only roots, fruit, vegetables,

milk foods, bread, and water. According to Saint-Just, no one was permit-

ted to either beat or caress a child, who, in turn, was not allowed to play

games that encouraged pride or self-interest. Emphasis was placed on

training students to express themselves well and succinctly in the French

language.

Schools were to be set up in the country, away from the towns. Saint-Just

wanted two kinds: primary schools, where children ages 5 to 10 would

learn to read, write, and swim. Secondary schools were to serve students

ages 10 to 16 and deal with both theoretical and practical agricultural sci-

ences (whereby farmers would be helped during the harvest) and military

sciences, including infantry maneuvers and cavalry exercises. As part of

the military curriculum, the young men were to be divided into compa-

nies and battalions each month, and the teachers would pick a promising

student to lead them. After reaching the age of 16 and passing the diffi cult

endurance test of swimming across a river before an audience on the day

of the Festival of Youth, a boy would be permitted to choose a trade and

leave school, but he was not allowed to see his parents before he reached

the age of 21, at which time he would be considered an adult. This program

was not followed, however, and the teaching and the educational system

122 Daily Life during the French Revolution

adopted by the Convention was, in fact, not so radical. It was governed

by three successive laws. The fi rst, enacted in December 1793, announced

that all compulsory primary schools were to be free for children ages 6 to

13, with the curriculum to emphasize politics and patriotism (for example,

study of the constitution, the decrees of the National Assembly, the Decla-

ration of the Rights of Man, and Common Law). Schoolchildren were also

to concentrate on physical education, among other subjects, and were to

take part in civic festivals. This program was diffi cult to implement due to

lack of money and time, so, in November 1794, a second law was passed

that made education no longer compulsory and that permitted nonstate-

run schools to operate.

As more attention was paid to reforming the educational system, teacher

training became one of the top priorities. Salary scales were established,

and committees of teachers were set up to run the schools and to meet

every 10 days. Educational policy became extremely centralized, and the

Committee for Public Instruction was to be responsible for the compo-

sition of textbooks used in the central schools. Unfortunately, as money

became harder to fi nd, teacher salaries soon became the responsibility of

local governments, to be paid by the parents.

A third law, passed in October 1795, required that students pay a small

fee to help pay for education in state schools; by then the government

under the Directory was in a state of fi nancial collapse. The parents were

once again given the choice as to whether their children would attend

offi cial institutions or be educated privately, and this meant that many

members of the clergy were able to maintain themselves by again open-

ing schools or becoming private tutors . To strengthen attendance at state

schools as opposed to religion-based institutions, and to gain a competi-

tive advantage over private schools, the government announced that any-

one who wished to work with the government must have evidence that he

had attended one of the republican schools.

In October of that year, the idea of schools for girls only was conceived, but

emphasis was placed on piety and morality, rather than on academic sub-

jects. By the late eighteenth century, in the south of France, about two-thirds

of boys were given some education, but only 1 girl in 50 was schooled .

25

Schools in many areas were in run-down, inadequate buildings. They

were short-staffed with mediocre teachers, there was a lack of books, and

undisciplined children ran wild. Truancy, a major problem, was often

encouraged by parents who had no confi dence in schools that were not

run by priests. In one town, mothers burned the few republican school-

books available. In Puy de Dôme, the Ecole d’Ambert listed an inventory

comprising “wretched furniture, rickety tables, empty bookshelves, and

dilapidated fl oors.”

26

Finding competent teachers was diffi cult. Some

of the candidates who applied to teach spelling, for example, could not

themselves spell; some who applied to teach mathematics could not add

up half a dozen fi gures correctly. With few qualifi ed candidates available,

Family, Food, and Education 123

the selection boards gave teaching certifi cates to many whose own educa-

tional level went barely beyond that of the pupils.

The current uniform, highly centralized, secularly controlled French

educational system that was begun during the Terror was completed by

Napoleon, under whom teaching appointments based on the results of

competitive examinations were opened to all citizens regardless of birth

or wealth.

NOTES

1. The archbishop of Narbonne, for example, had a princely income of 400,000

francs, but when he fl ed the country for safer ground, he left a debt of 1.8 million

francs. See Madame de la Tour du Pin, 315.

2. Quoted from Desan, 102.

3. Robiquet, 78.

4. Hunt (1992), 40; McPhee, 200.

5. Robiquet, 81.

6. Young, 306.

7. Even “a journeyman carpenter in France has his napkin as regularly as his

fork; and at an inn, the fi lle [waitress] always lays a clean one to every cover that is

spread in the kitchen, for the lowest order of pedestrian travellers.” Ibid., 307.

8. L.-S. Mercier, Tableau de Paris (1782), vol. I, 228–29, in Braudel, 260.

9. L.-S. Mercier, Tableau de Paris (1782), vol. XI, 345–46, in Braudel, 187–88.

10. Dr. John Moore, “Journal during Residence in France” (1793), in Tannahill,

6, where he gives an account of the last few months of 1792—a time when there

were few foreigners remaining in Paris.

11. Louis XVI fasted; his family did not.

12. Braudel, 169–70.

13. See Robiquet, 112, for more detail.

14. Ibid., 202–4.

15. Tench, 82.

16. Robiquet, 19.

17. Braudel, 246.

18. The Jesuits dominated French higher learning from the sixteenth century

until 1764, when they were expelled, leaving the educational system in France

in turmoil. Out of about 400 colleges in all of France, the Jesuits had run 113, and

these were subsequently taken over by other religious orders or by secular priests.

The original Congregation of the Oratory was founded in Rome in 1575; shortly

thereafter, it became a distinct institution in France. It was suppressed during the

revolution and reconstituted in 1852 as the Oratory of Jesus and Mary.

19. Lewis (2004), 160.

20. Brockliss, 55.

21. Ibid.,100 ff. for more detail.

22. Ibid.,105.

23. Ibid., 45.

24. Robiquet, 81.

25. Wiesner, 123.

26. Quoted in Robiquet, 84–85.

8

Health, Medicine,

and Charity

In large part because of the lack of hygiene and the poor living conditions,

the population in France in the early eighteenth century was faced with

epidemic diseases as a common occurrence. In large cities such as Paris,

drains and drinking water intermingled, animal and human dung in the

streets fi ltered through the soil into the groundwater with every rainstorm,

and fl ies in summer contaminated the food in the markets. Even those

affl uent enough to order water brought by the bucketful to their doors

were not safe, because the water came from the river Seine. Daily living in

Paris was not a healthy experience, and smallpox and scarlet fever struck

often and spread rapidly. Typhoid fever was never far off, and malaria

was a curse for those living near stagnant water and its breeding mosqui-

toes. Further, dysentery was a major problem, and shortages of fresh food

often led to outbreaks of scurvy.

Among the poor, illness routinely cut a swath through the young and

old, sometimes leaving entire communities devastated. Such was the case

about 20 years before the revolution, when typhus raged through Brittany,

decimating the local population.

The health of workers in industry was affected by employment condi-

tions. Thread fl ax workers, for example, labored in damp circumstances

to safeguard the thread. Many of them not only developed debilitating

arthritis but also, often fatally, contracted pneumonia. Weavers and lace-

makers, who performed precise and intricate labor, often worked in poor

light that rendered them prone to serious eye problems, even blindness.

Tuberculosis took its toll of girls doing menial work in silk and paper

126 Daily Life during the French Revolution

manufacturing, while those working with glass and metal were subject to

lung diseases. Tailors and shoemakers, after years of hunching over their

work, were sometimes left crippled.

At this time, people, especially the poor, had little use for doctors.

When they became ill, most took the matter into their own hands, trying

to improve their diet, drinking more red wine for its health benefi ts, and

putting their faith in the saints. The poor suffered great agonies before

going to a doctor or a hospital—the former was expensive, the latter usu-

ally a place to die.

Common problems encountered by the poor included cataracts, sprains,

burns, and broken bones. Many men developed hernias from performing

heavy work, but unless the condition brought their ability to earn their

livelihood to a halt, they generally did not consult a doctor, who, to diag-

nose the problem, would examine the patient’s stools, vomit, and spittle,

prescribe various powders and pills and then perform a bloodletting, the

panacea for nearly everything from recovery after childbirth to smallpox.

Although ideas about medicine were undergoing change, the practice,

especially in rural areas, was still medieval.

In the countryside, faith in physicians was rare, and when an epidemic

struck, a fatalistic apathy took hold. There were no effective pain relievers

and no antiseptics available, and for country people, care from itinerant

healers or quacks, with their plasters and ointments, a visit to the village

blacksmith, who set bones, or the drinking of mineral waters or potions

concocted by the local wise woman all were preferable to seeking outside

treatment. A tanner from the Perché region, for example, sold an eyewash

containing alum, green vitriol, and dog excrement in the 1780s.

1

If outside

treatment was sought, it was more likely to be from a surgeon than a phy-

sician, even though the surgeon might be barely literate and know only

how to bleed, purge, or shave the patient.

2

PHYSICIANS AND SURGEONS

The best doctors were almost always to be found in cities, and, with their

superior university background, physicians were considered much more

distinguished than surgeons. Medical courses were still based on centuries-

old classical Latin texts and were far from arduous in any empirical sense.

It was entirely possible for a doctor to complete his medical studies with-

out ever visiting the bedside of an ill person. It cost some 7,000 livres to be

registered, but the majority of doctors were middle- or upper-level bour-

geois who were able to start fashionable practices and soon recoup their

expenses by charging high fees.

For common people, doctors were not only feared; they were also

economically out of reach. Doctors were traditionally represented as a

rapacious group whose few minutes of advice cost a worker several days’

Health, Medicine, and Charity 127

pay. The complaint was that all a doctor cared about was prestige and

wealth. A government survey, conducted as late as 1817 to assess the geo-

graphical distribution of medical personnel, reported that there were still

many rural areas without doctors, who continued to be distrusted and

avoided by the local populace .

3

Surgeons, on the other hand, were respected by the poor because they

worked with their hands. Before 1743, their training rarely involved atten-

dance at university. Instead, they were required to do an apprenticeship

under a tutor. Previously known as barber-surgeons, these men once

cut hair, shaved clients, pulled teeth, stitched up or cauterized wounds,

treated dislocated bones, and handled a host of other maladies for which

the lofty physician would not dirty his hands. For many years, surgeons

strove to combat their perceived association with barbers. A small percent-

age of those living and working in the capital earned good money, but

most surgeons lived on much less. In the provinces, the average income

of a surgeon was only around 1,000 livres. While the poor preferred to go

to the quack, they might consult the surgeon on occasion for some kind

of treatment.

HOSPITALS

Of the 2,000 or so hospitals in France under the old regime, some con-

sisted of only one room staffed by a couple of nuns in a rural village. Others

were large public institutions like the Hôtel-Dieu in Paris. By 1789, most

major cities were equipped with a general hospital that could attend

to routine illnesses, as well as care for the elderly. Bordeaux had seven

hospitals of varying size and effi ciency, and the facility in Paris comprised

a number of buildings.

4

For many people, with no resources, these disease-

infested places, dreaded as the ultimate refuge, amounted to a dingy and

pathetic place to die.

Poor hygienic conditions and the failure to segregate those with con-

tagious diseases from people suffering from broken bones (although the

wealthy could obtain a separate room, since their good treatment augured

well for charitable donations) were the result of both lack of fi nancial

resources and power struggles within the institutions.

Poor sanitary conditions were often aggravated by the fact that many

hospitals were situated on the edge of town next to cemeteries, refuse

dumps, and the municipal abattoir or close to fetid rivers and streams,

giving rise to humid and overpowering odors.

5

Daily life in the hospital often involved stormy sessions between doctors

and the nursing sisters. For instance, in 1785, at the Hôtel-Dieu in Montpellier,

the royal inspector of hospitals and prisons, Jean Colombier, insisted on the

subordination of the sisters to the medical staff, who accused the sisters,

among other things, of overfeeding the patients. The Mother Superior

128 Daily Life during the French Revolution

resigned because the doctors were given more sway than the sisters in the

internal affairs of the hospital. Championing better hygiene, the doctors

clashed with the sisters, and the struggle for supremacy became one of

traditional sympathy and consolation versus scientifi c and therapeutic

treatment. The management and the sisters both insisted that the hospital

should be a charitable institution, rather than a medical one. The admin-

istration (made up of the city’s elite) preferred to see medical care admin-

istered in the home and believed that the emphasis in the hospital should

be put on the spiritual and material wellbeing of the patients.

The buildings themselves were often in a sorry state of disrepair. Fre-

quently, the walls were crumbling, the roofs leaked, and broken windows

precariously adhered to rotting frames. The money for upkeep was not

always there, and the shortage grew worse throughout the eighteenth

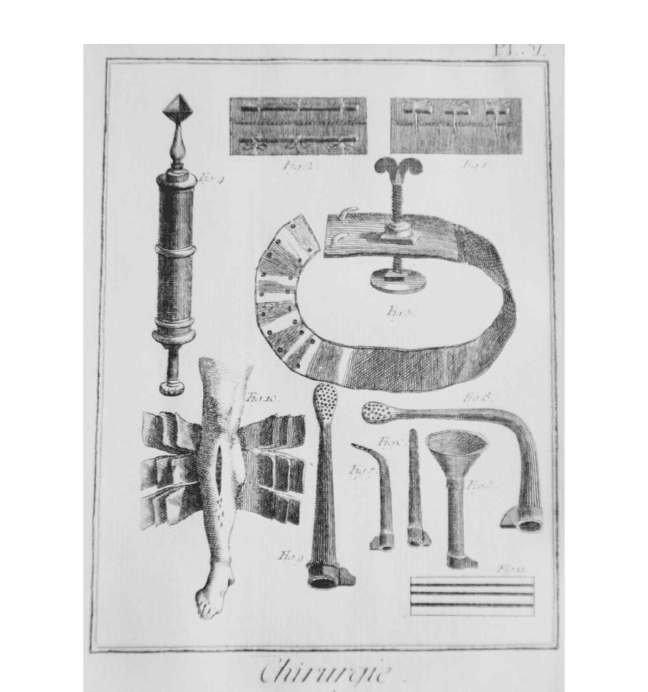

Surgical equipment ca. 1770, showing a wound compress

comprising a hooked leather strap, leg binding, and several

other items.

Health, Medicine, and Charity 129

century. The straw beds were breeding places for lice, fl eas, and germs,

and in summer months, beds crawling with vermin became unbearable.

Further, ventilation was often poor, and the stench of urine and excretion

was sometimes overwhelming. Lack of hygiene in overcrowded rooms

constituted an extreme health hazard in many hospitals. Sometimes two

or three people, each with different diseases, might occupy the same bed,

and straw was distributed around the fl oor for those without a mattress

to lie on. On occasion, a patient entered a hospital with one ailment and

contracted another there, one that could be fatal. Smallpox ran through

the children’s wards and led to many deaths. Tinea and scabies were often

endemic, typhus and dysentery were sometimes introduced, often by sick

soldiers, and gangrene, too, was a problem.

In winter, heat was precious, and lack of hot-water bottles, foot warm-

ers, and braziers meant that elderly patients developed hypothermia and

pneumonia. For young children and the elderly, the hospital was too often

the gateway to the grave.

As some progress was made in the understanding and control of dis-

ease, most doctors became aware that good food and hygienic conditions,

as well as the isolation of patients with contagious diseases, played a part

in health. Such measures, however, were often sporadic, incomplete, and

not economically viable.

Confl ict arose over the use of corpses for anatomical research on the

workings of the human body. This, along with teaching, was fi rmly

opposed by the sisters and the administration. When teaching was allowed,

procedural regulations were strict so as not to offend the sensitivity of the

nurses, who also felt that the sick and poor should not be molested by

students asking questions and trying to examine them.

The medical profession’s demands eventually convinced hospital staff

to allow some dissection of bodies, but, apart from executed criminals, few

bodies were procurable. In some instances, doctors, surgeons, and medi-

cal students in private schools took liberties such as raiding graveyards,

often treating the remains in a cavalier manner once they had fi nished

their dissection. Body parts were dumped outside the cities in heaps or

thrown into a river, where bits might wind up at a public washing site.

As a result of the contentious situation, doctors vied with one another

to acquire posts in military garrisons, prisons, and the new Protestant hos-

pital in Montpellier, where they had direct access to the sick without the

obstructive infl uence of nursing sisters and administrators.

Whenever possible, people, even of modest means, avoided hospitals;

hospital admissions were usually not confi dential, and the experience was

humiliating. Those who were desperate enough to enter the General Hos-

pital in Montpellier, for example, had to appear before the full administra-

tion board of the institution, headed by the bishop, and a committee of the

city’s prestigious nobles. There, as often as not in rags, they pleaded their

case for acceptance. If they were admitted, their effects were confi scated,