Amaro A., Reed D., Soares P. (editors) Modelling Forest Systems

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 116

116

Table 10.2. Effect of first thinning on dominant breast height girth.

Plot H

dom

a

(m) i

th

b

(%) kg

c

Dom-sy

d

(%) Dom-se

e

(%) Gbh

be

f

(cm) Gbh

af

g

(cm) Bias

rel

h

(%)

DR31 B 3.95

DR19 H 4.72

DR19 G 4.82

DR19 D 4.83

DR19 F 5.01

DR19 J 5.10

DR19 C 5.16

DR11 C 6.11

DR18 C 7.12

DR18 A 7.19

ER40 H 8.92

ER40 J 9.08

ER40 S 9.20

ER40 I 9.20

ER42 B 10.63

ER42 D 11.04

ER40 L 11.05

ER40 R 11.11

65.0

73.0

62.2

77.4

54.4

45.1

63.0

62.8

60.8

52.7

37.7

66.9

75.4

52.1

67.0

55.0

49.3

52.1

0.89

1.00

0.95

0.97

0.93

1.01

0.95

0.99

0.99

1.01

1.04

0.94

0.93

0.98

0.94

0.97

0.89

0.90

22.2

62.5

37.5

12.5

25.0

25.0

37.5

44.4

22.2

20.0

25.0

8.3

8.3

8.3

16.7

25.1

8.3

8.3

11.1

37.5

0.0

87.5

37.5

50.0

37.5

11.1

55.6

50.0

33.3

75.0

66.7

58.4

50.0

33.3

25.0

41.7

22.6

36.1

33.8

34

33.5

33.8

34.4

41

46.2

47.2

68.5

70.4

71.5

72.1

64.1

66.6

76.8

76.9

22 2.5

27.4 24.2

31.4 7.0

28.4 16.5

30.1 10.1

29.9 11.5

31.8 7.6

38.9 5.1

42.2 8.7

44.4 5.9

63 8.0

64.3 8.8

65.8 8.0

64.8 10.2

60.8 5.2

63.8 4.1

74.7 2.8

74.7 2.9

a

Dominant height.

b

Thinning intensity expressed as the proportion of cut trees.

c

Thinning nature expressed as the ratio between the mean cut tree basal area and the mean tree basal area before thinning.

d

Proportion of dominant trees felled by systematic thinning.

e

Proportion of dominant trees felled by selective thinning.

f

Mean breast-height girth of dominant trees before thinning.

g

Mean breast-height girth of dominant trees after thinning.

h

Relative bias expressed as 100 (gbh

af

gbh

be

)/gbh

be

.

C. Meredieu et al.

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 117

117 Modelling Dominant Height Growth

As we reconstituted the past height growth of all these trees, we were able to

calculate all the possible dominant height values during the growth period (Table

10.3).

First thinning slightly reduced dominant height. The differences evolved from a

few centimetr

es to 44 cm as a maximum value and were not significant (threshold

95%) with only one exception (plot DR31 (P = 0.019)). Thinning had no significant

technical effect on the calculated dominant height.

Density effect on dominant height increment

Homogeneity of plot fertility in each stand

One of the interesting characteristics of the site index theory is that productivity can

be estimated from height growth alone over a rather wide range of stand densities.

The only way to check this assumption is to apply density treatments to the plots

having similar topography, soil and past use, so that they can be assumed to have an

equal productive potential.

Each experiment was conducted in a homogeneous stand with the same past

silvicultural management. No thinning was performed befor

e the beginning of the

experiment; only weed control was carried out. Therefore, the only difference

between the plots of each experiment at the beginning of the growth period was the

site fertility. In order to check the uniformity of the site fertility, we used the calcula-

tion of dominant height as an indicator of site fertility.

The ANOVA showed no significant differences at the threshold 95% for the

plots of the same experiment. Thus, we concluded that the plots had the same site

fertility

. Nevertheless, the analyses showed a significant difference at the 90%

threshold for the plots of two trials: DR19 and DR31.

Relationship between dominant height increment and Hart–Becking index

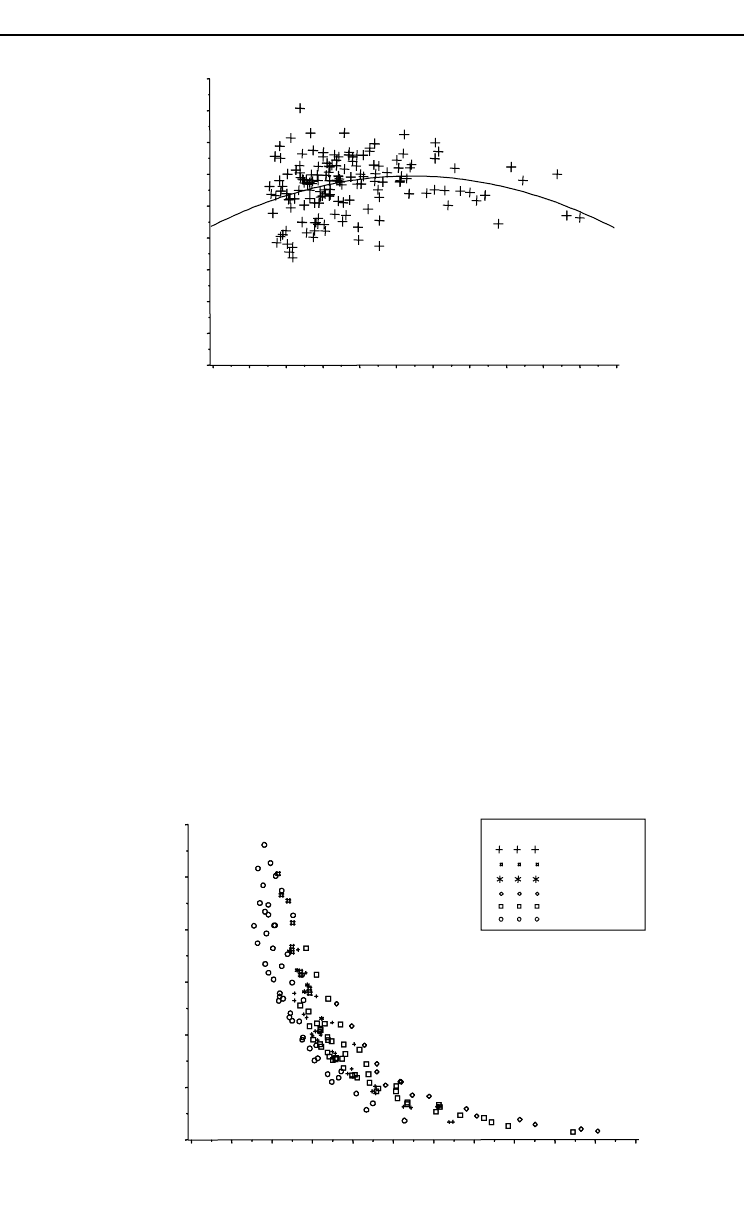

Figure 10.2 shows dominant height increments in each plot by 2-year period vs.

Hart–Becking index. T

wo trends were identified: dominant height increment was

lower for both the lowest and the highest values of the Hart–Becking index.

Table 10.3. Technical effect of first thinning on dominant height (H

dom

).

Plot H

dom

be

a

(m) H

dom

af

b

(m) Bias

c

(m) Bias

rel

d

(%)

DR31 A 4.29 3.84 0.44 10.3

DR11 A 6.31 6.26 0.06 0.9

DR19 E 5.06 5.05 0.01 0.3

DR19 I 5.27 4.98 0.29 5.4

DR15 A 8.72 8.58 0.15 1.7

DR18 B 7.08 7.05 0.02 0.3

ER40 M 9.11 8.97 0.14 1.5

ER42 A 10.71 10.68 0.04 0.3

a

Dominant height before thinning.

b

Dominant height after thinning.

c

Bias expressed as H

dom

af

–H

dom

be

.

d

Relative bias expressed as 100 bias/H

dom

be

.

Calculation of a relative mean dominant height increment

To avoid the variability due to site fertility between the different experiments, a rela-

tive mean dominant height was calculated for each combination plot 2-year period.

The ratio between mean dominant height increment for each combination plot 2-

year period and the maximum dominant height increment of the experiment for the

same growth period provided a rate of growth for a plot vs. a potential increment.

Relationship between relative dominant height increment and stand density indices

Independent variables (i.e. the predictors) such as SDI, BA, RSI (calculated at the

beginning of the 2-year period) and variation of the RSI over the 2-year period were

tested against the relative dominant height increment.

The Hart–Becking index appeared to be an appropriate indicator for taking into

account the variation of stand density in plots with a very low number of stems (Fig.

10.3).

118 C. Meredieu et al.

Thinning intensity

1100_delayed

1400

500

800

Control

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

1100

RSI

Basal area (m

2

/ha)

Fig. 10.3. Basal area vs. Hart–Becking index (RSI).

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

0 10 20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100 110

Dominant height increment (cm)

RSI

Fig. 10.2. Dominant height increments for each plot by 2-year period vs. Hart–Becking index (RSI).

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 118

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 119

119 Modelling Dominant Height Growth

Hart–Becking index confirmed the link between these two variables. Relative domi-

not significant.

Discussion

ent species and in particular in the Pinus species: Pinus pinaster (Illy and Lemoine,

Relative dominant height increment

RSI by classes

20 30 40 50 60 70 80 90 100

50

60

70

80

90

100

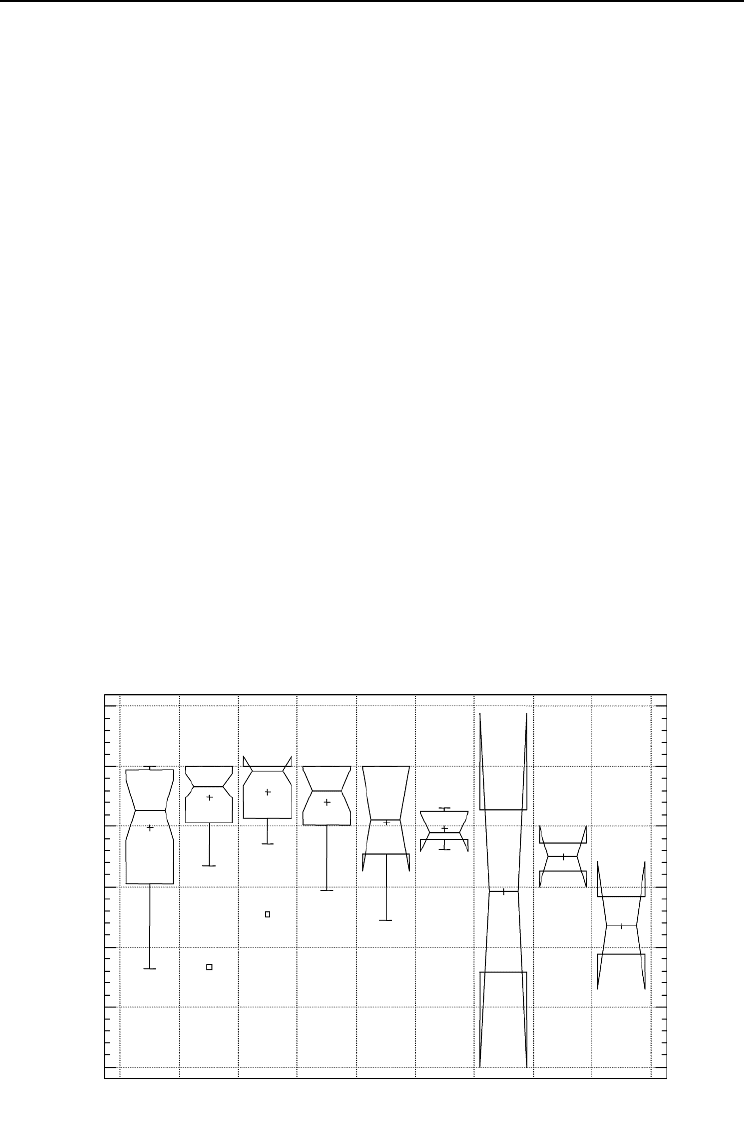

The ANOVA of the relative mean increment of dominant height vs. the

nant height increment was lower with a high Hart–Becking index (Fig. 10.4). A simi-

lar trend was observed for the lower level of Hart–Becking index but this trend was

According to our observations, an optimal zone of dominant height increment

can be defined: between 17 and 62%. Outside this zone, none of the plots reached

the maximum relative dominant height increment.

These new data analyses showed the density-dependence of height growth in domi-

nant trees. This result was obtained using a wide range of experimental stands, i.e.

27 experimental plots of Corsican pine planted in the region ‘Centre’ (France) and

managed with different thinning intensities. The choice of dominant trees was con-

sistent with the usual definition (Pardé and Bouchon, 1988) and was not biased by

other criteria such as the tree form or the spatial distribution in the stand. When

such criteria are added, this dominant population could get close to the definition of

crop tree population and the values of dominant height or dominant girth could

decrease.

Lloyd and Jones (1982) have pointed out the influence of stand tree number on

dominant height for loblolly pine and for slash pine: dominant height growth was

reduced when stand density increased. In lodgepole pine stands, growth reduction

can be dramatic in dense, stagnant stands (Cieszewski and Bella, 1993). Such growth

reduction can also be noticed in very open stands (Pardé and Bouchon, 1988), or on

less productive sites (Braathe, 1957). This phenomenon has been observed in differ-

110

Fig. 10.4. Box and whisker plot: dominant height increments for each plot and every 2-year period vs.

Hart–Becking index (RSI).

1970; Lemoine, 1980), Pinus contorta (Ottorini, 1978; Cieszewski and Bella, 1993) and

Pinus sylvestris (Braathe, 1957).

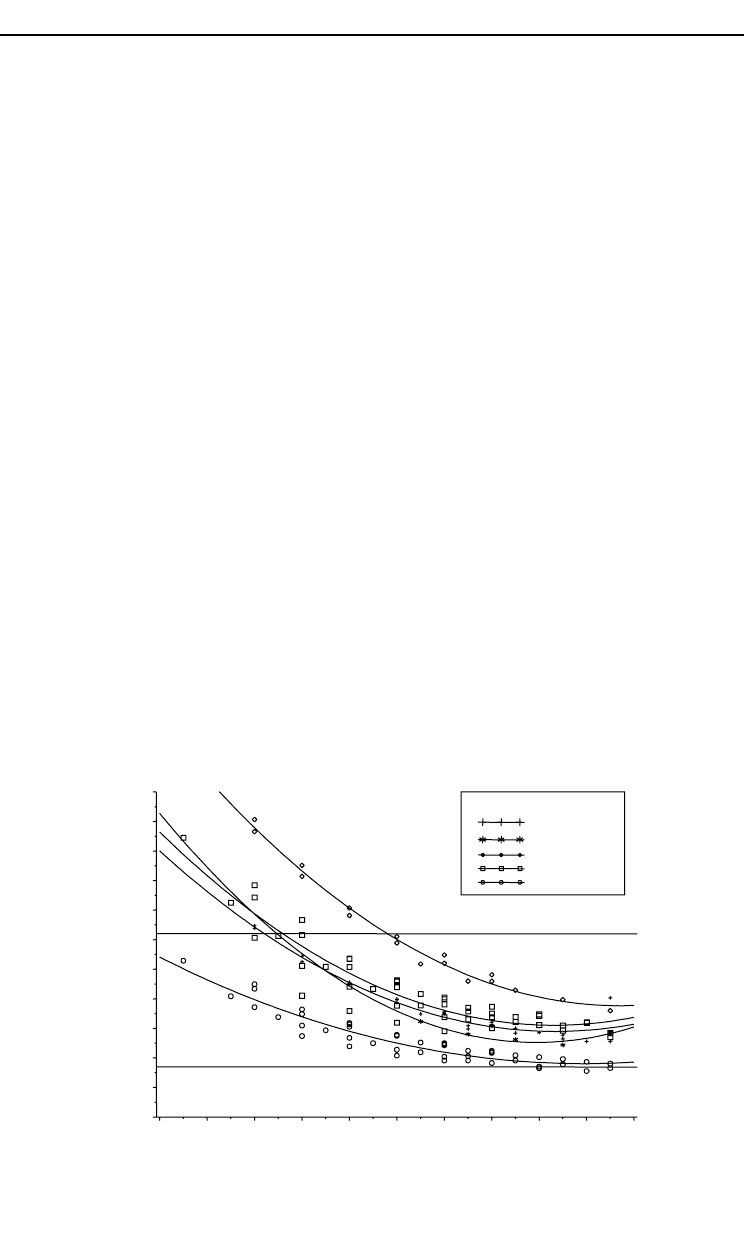

In our study, we showed that there is an optimal zone of dominant height

growth which is a function of the Hart–Becking index (Fig. 10.5). For a Hart–Becking

index between 17 and 62%, the observed plots had a maximum relative dominant

height increment (value = 100). Nevertheless, density-dependence could change

during the life of the stand (Cieszewski and Bella, 1993). Our hypothesis is that the

influence of stand density increases in magnitude in young and intermediate-age

stands as crowding intensifies, until it reaches a certain stability in mature stands.

Figure 10.5 illustrates this assumption: with the increase in age and with moderate

thinning regimes, stand density reaches a mean value around 15–20% for a

Hart–Becking index which is in the optimal zone. Thus, in mature stands where the

range of stand density is narrowed, the effect of density on height could probably be

not significant.

Our data did not show any effect of site fertility on the relationship between

stand density and dominant height growth such as reported by Braathe (1957) or

Ottorini (1978). Furthermore, all experimental plots were measured during the same

growth period, so climatic factors might have interacted with the stand density

effect.

Future Directions

We confirm the existence of a density-dominant height effect in the early stages of

development (below 30 years old) and for a Hart–Becking index below 17% and

above 62%. Consequently, a model to determine dominant height growth needs to

combine site fertility, age and Hart–Becking index such as:

H

dom

= f(H

dom30

, Age, RSI)

where H

dom30

is the dominant height at age 30 (breast height age).

120 C. Meredieu et al.

RSI

Thinning intensity

1100

500

800

Control

0

10

20

30

40

50

60

70

80

90

100

110

Age

10 12 14 16 18 20 22 24 26 28 30

1400

Fig. 10.5. Relationship between Hart–Becking index and total age for a range of thinning intensities. The

horizontal lines show the optimal height growth zone (between 17 and 62%).

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 120

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 121

121 Modelling Dominant Height Growth

Another solution would be to build site index curves for a fixed density and,

thereafter, to correct it with a function of the Hart–Becking index.

In the growth model SPS, Arney (1985) used a negative effect of stand density

on dominant height growth for the highest stand density.

In the ‘tree–distance independent’ growth model built for Corsican pine in

France (Mer

edieu, 1998), the dominant height growth relationship included a stand

density effect in addition to age at breast height and site index effects.

Diameter growth has been described and fitted as the product of potential

gr

owth (POT), and reduction factors, or modifiers, to quantify global competition

within the stand (RED1) and the status of the tree in the stand (RED2).

DIAMETER GROWTH = POT RED1

RED2

The potential term can be related to site fertility through dominant height incre-

ment. In or

der to take the influence of density into account, instead of using real

dominant increment, we could use the corrected term of dominant height increment

with the optimum density index.

Thus, the potential term of diameter growth could account for site fertility, age

and period of gr

owth through the dominant height increment.

Further studies are needed to improve the relationship between density index

and dominant height gr

owth and to connect this relationship with the potential

term of the diameter growth relation.

References

Arney, J.D. (1974) An individual tree growth model for stand simulation in Douglas-fir. In:

Fries, J. (ed.) Growth Models for Tree and Stand Simulation. Research Notes, Royal College of

Forestry, Stockholm 30, 38–46.

Arney, J.D. (1985) A modelling strategy for the growth projection of managed stands. Canadian

Journal of Forest Research 15, 511–518.

Braathe, P. (1957) Thinning in Even-aged Stands: a Summary of European Literature. Faculty of

Forestry, University of New Brunswick, 92 pp.

Cieszewski, C.J. and Bella, I.E. (1993) Modeling density-related lodgepole pine height growth,

using Czarnowski’s stand dynamic theory. Canadian Journal of Forest Research 23,

2499–2506.

Illy, G. and Lemoine, B. (1970) Densité de peuplement, concurrence et coopération chez le pin

maritime. I. Premiers résultats d’une plantation à espacement variable. Annales des

Sciences Forestières 27, 127–155.

Inventaire Forestier National (2002) Available at: www.ifn.fr

Krajicek, J.E., Brinkman, K.A. and Gingrich, S.F. (1961) Crown competition: a measure of den-

sity. Forest Science 7, 35–42.

Lemoine, B. (1980) Densité de peuplement, concurrence et coopération chez le pin maritime. II.

Résultats à 5 et 10 ans d’une plantation à espacement variable. Annales des Sciences

Forestières 37, 217–237.

Lloyd, F.T. and Jones, E.P. (1982) Density effects on height growth and its implications for site

prediction and growth projection. In: 2nd Biennial Southern Silvicultural Research

Conference, USDA GTR SE-24. 4–5 November, Atlanta, Georgia, pp. 329–333.

Meredieu, C. (1998) Croissance et branchaison du Pin laricio (Pinus nigra Arn. ssp. laricio (Poir.)

Maire): élaboration et évaluation d’un système de modèles pour la prévision de carac-

téristiques des arbres et du bois. MSc thesis, Université Cl. Bernard Lyon I, Lyon, France.

Ottorini, J.M. (1978) Aspects de la notion de densité et croissance des arbres en peuplement.

Annales des Sciences Forestières 35, 299–320.

Pardé, J. and Bouchon, J. (1988) Dendrométrie, 2nd edn. In: ENGREF (ed.), Nancy, France, 328 pp.

Reineke, L.H. (1933) Perfecting a stand-density index for even-aged forests. Journal of

Agricultural Research 46, 627–638.

12Amaro Forests - Chap 10 25/7/03 11:05 am Page 122

13Amaro Forests - Chap 11 1/8/03 11:52 am Page 123

11 Testing for Temporal Dependence

of Pollen Cone Production in Jack

Pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.)

S. Magnussen,

1

F.A. Quintana,

2

V. Nealis

1

and

A.A. Hopkin

1

Abstract

Nine-year records of the presence or absence of pollen cones (microsporangiate strobili) in 1299

jack pine trees growing in 38 locations (plots) across northern Ontario were tested for temporal

dependence. The null hypothesis of a zero-order Markov chain was tested with three statistics

at the tree level and at the location level. Tree-level test results were generally in agreement.

Only about 5% of the trees had records indicating a significant departure from the null hypoth-

esis. About one-third of the trees carried pollen cones every year or not at all. After adjustment

for multiple comparisons, no trees violated the null hypothesis. Location-level tests relied on

Monte-Carlo reference distributions. Depending on the test statistic, we found 2–15 locations

with significant departures from the null hypothesis. Conditional (on location) temporal inde-

pendence is accepted as a reasonable working model. A binomial model described reason-

ably well the overall frequency distribution of the number of years (out of nine) with pollen

cones. The intra-location correlation coefficient of pollen cone production was strong (0.40).

Introduction

Jack pine (Pinus banksiana Lamb.) growing in Canada’s boreal and sub-boreal forests

and in the Lake States of the USA is subject to periodic defoliation by the jack pine

budworm (Choristoneura pinus pinus Freeman) causing significant mortality and

growth losses (Gross, 1992; Conway et al., 1999; Hall et al., 1999; Volney, 1999;

McCullough, 2000). Pollen cones (microsporangiate strobili) constitute a food source

critical for the survival and vitality of jack pine budworm larvae when they emerge

in the early spring (Rose, 1973; Nealis and Lomic, 1997). In the absence of defoliation,

pollen cones are produced in great abundance in most years (Benzie, 1977; Rudolph

and Yeatman, 1982), yet climate, soil properties, and tree crown characteristic mod-

ify the periodicity and frequency of production. Trees defoliated by the budworm

often respond by a marked decline in the production of pollen cones the following

1

Natural Resources Canada, Canadian Forest Service, Canada

Correspondence to: smagnuss@PFC.Forestry.CA

2

Department of Probability and Statistics, School of Mathematics, Pontificia Catholic University of Chile,

Chile

© CAB International 2003. Modelling Forest Systems (eds A. Amaro, D. Reed and P. Soares) 123

13Amaro Forests - Chap 11 1/8/03 11:52 am Page 124

124 S. Magnussen et al.

spring (Nealis, 1990; Nealis and Lomic, 1997; Nealis et al., 1998). Quantification of

the decline in pollen cone production induced by defoliation of the jack pine bud-

worm requires an understanding of the temporal dynamics of pollen cone produc-

tion in the absence of defoliation. Is the presence of pollen cones on an undisturbed

tree in year t independent of the presence/absence of pollen cones the previous year

(t 1)? Many coniferous forest tree species show periodicity of seed set and pollen

cone production (Smith, 1997) which, everything else being equal, points to a lack of

temporal independence. A lack of temporal independence carries with it the poten-

tial of confounding ‘carry-over effects’ (Kunert, 1987; Matthews, 1990; Yang and

Tsiatis, 2002) in simple estimates of temporal contrasts of pollen cone production.

This study tests the hypothesis of temporal independence of the production

(pr

esence/absence) of jack pine pollen cones during a period of 9 years in undis-

turbed stands in northern Ontario, Canada. Hypotheses of temporal independence

are tested at both the tree and at the location (plot) level.

Materials and Methods

Data from 1299 jack pine trees located in 38 plots across Ontario (Canada) are used

in this study. The plots are part of a network of 180 Forest Insect and Disease

Survey plots established in 1992. Each plot contained 50 dominant/codominant

mature jack pine trees (age 30–110 years). Tree size, crown characteristics and

health status were recorded for all trees in 1992. Defoliation by the jack pine bud-

worm (%) and the presence/absence of pollen cones were recorded for all trees

from 1992 to 2001. Counts of egg masses and surviving larvae were completed

(1992–1998) on branch samples taken from a subset of ten trees from each plot. The

1299 trees used in this study are the set of trees in the data with no defoliation dur-

ing the 9 years of observation. Defoliation prior to the first observation is consid-

ered unlikely because the plots were established in a quiescent period between two

outbreaks of the budworm. Data records consist of tree and location identifiers and

nine binary scores indicating annual presence (1) or absence (0) of pollen cones

between 1992 and 2001.

Binary Markov chains of pollen cone scores

We assume that each individual series of binary scores forms a stationary Markov

chain of some or

der (Kedem, 1980). A zero-order chain implies temporal indepen-

dence of scores and indicates that the presence and absence of pollen cones depend

only on the long-term average (stationary mean) and not on past patterns of pollen

cone production. In a first-order chain, the conditional distribution of the state in

year t given the whole sequence of observed past states depends only on the state in

year t

1. For second-order chains this dependency is extended to t

2, etc.

Let x for t = 0,1,...,

n form a binary Markov chain of ith order (x

t

= 1 if pollen

t

cones are present, and 0 if absent) with expectation (over time) E (x

t

) = p. For a

t

binary sequence x

0

,x

1

,x

2

,...,x

t

the probability of the transition from x

t1

to x is:

t

x

t

x

t

1−x

t −1

(1)

P = (p × (1 − p

11

)

1−x

t

)

x

t −1

×

(

p

10

× (1 − p

10

)

1−x

t

)

x

t −1

x

t

11

where p

11

and p

10

are the one-step transition probability that a score of 1 is followed

by a score of 1 and 0, respectively. By extension, we obtain the probability of three

successive scores as:

13Amaro Forests - Chap 11 1/8/03 11:52 am Page 125

125 Temporal Dependence of Pollen Cone Production

x

t−2

−

1

x

t

=

(

1−x

t

011

)

x

t−1

×

(

x

t−1

1−x

t

x

t

x

t

P

x

t−2

x

t−

× p × p

p

111

p

101 001

(2)

−1 x

t−2

1

)

−

1

After further expansion, the joint distribution of a time series x

1

,...,x becomes:

n

n

)( ) (

x

t

x

t− −1 1

− −1 1x

t

x

t

x

t

x

t

× × × ×p

110

p p

100

p

010 000

)

1−

II ,,

12

×

∏

12

,,

…

…

I

−

x x

(3)

(1P

x

1 1

t

= p p p

ii ix,,

where the second product is over all 2

t

0–1 t-tuples (i

1

,i

2

,...,i

t

) and

…

1 tn

2t=

1

Hence the product I

1

I

2

...I

t

is a sufficient statistic for the chain. Given a binary

time series x

1

,...,x the number of observed transitions i

1

,i

2

,...,i

k

of order k is defined

n

}. It follows that T

k

is a sufficient statistic for the binary time series. Inas T

k

={t

i

1

i

2

,...,i

k+1

other words, counting transition patterns suffice for the statistical inference of a

binary time series.

A subsequence in a binary time series consisting of identical scores (0 or 1) is

called a r

un (streak). The number of runs in a series of length n is denoted by R .

n

Although not a sufficient statistic, R

n

, due to ease of interpretation and known zero-

order distribution (Swed and Eisenhart, 1943), is often used for testing the temporal

randomness of a binary sequence.

Tests of temporal independence of pollen cone scores

Values of R and T

k

(k = 1) were obtained for each tree and compared with the prob-

n

ability of obtaining a similar or more extreme value under the null hypothesis of a

zero-order Markov chain (temporal independence of pollen cone production).

Under the conditional (on n, u

and v) null hypothesis of temporal indepen-

dence, the probability of obtaining R

ˆ

n

runs in a sequence of length n composed of u

ones and v zeroes (we assume without loss of generality that u ≤ v ) is (Swed and

Eisenhart, 1943):

xiif 1=

t t

(4)

I

t

=

− xiif

0=

t t

( (

×

) )

(

R

ˆ

n

−1 −1

−1

u v

2 for× even

+uv

(5)

R

ˆ

R

ˆ

−

(

×

)

21 −

+

21

PR n u v(

ˆ

|,

n

/ /

)

n n

×=

,

(

) (

×

)

− )/12

)

otherwiseotherwise

u

− − − −1 1 1 1u v u v

R

ˆ

R

ˆ

R

ˆ

R

ˆ

− − −( )/12 ( )/32 ( )/32 (

n n n n

∞

→

a

where the binomial coefficient

()

is the number of different arrangements of b ele-

b

ments of one kind and a-b elements of another kind (Jeffreys, 1961). The conditional

null distribution of

ˆ

R is obtained by computing the pr

obability of each possible

n

number of runs given the observed values of u, v and the constraint u + v = 9.

When the null hypothesis of complete randomness (no temporal dependency)

of the individual binary scor

es is true, we would expect, conditional on x

1

(the first

binary score), the number of ‘00’ sequences to be similar to the number of ‘10’

sequences. Hence, the test statistic U

0,1

(X) defined in Equation 6 (Quintana and

Newton, 1998) as a function of the vector X of observed binary scores tends to zero

for n when the null hypothesis is true.

2

t

t

10

U

ˆ 00

−(|X = 9)

=

, ,x

1

u v n

(6)

,

,01

+ +t t t

10

t

1101 00