Adelaar Willem, Muysken Pieter. The languages of the Andes

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

184 3 The Inca Sphere

LORETO

UCAYALI

PASCO

San Pedro de Cajas

Ta r m a

Jauja

Concepción

APURIMAC

JUNÍN

MADRE DE DIOS

Apolo

Coata

Cuenca

Saraguro

Lamas

SAN MARTÍN

Cañaris

IMBABURA

Quito

COTOPAXI

Salasaca

CHIMBORAZO

CAÑAR

LAMBAYEQUE

LA LIBERTAD

Pallasca

ANCASH

Cajatambo

Paccho

Pacaraos

Laraos

Yauyos

C

U

Z

C

O

PUNO

AREQUIPA

M

O

Q

U

E

G

U

A

TACNA

A

Y

A

C

U

C

H

O

ICA

A

M

A

Z

O

N

A

S

C

A

J

A

M

A

R

C

A

Piura

HUÁNUCO

LIMA

H

U

A

N

C

A

V

E

L

I

C

A

COLOMBIA

ECUADOR

PERU

BRAZIL

CHILE

B

O

L

I

V

I

A

Tumbez

Chiclayo

Cajamarca

Trujillo

Chachapoyas

Moyobamba

Pucallpa

Huaraz

Lima

Cuzco

Pto. Maldonado

Arequipa

Tacna

Puno

Moquegua

Abancay

Ayacucho

Ica

Huancavelica

Huancayo

C

h

o

n

g

o

s

B

a

j

o

Cerro de Pasco

Huánuco

Iquitos

PIURA

TUMBEZ

Ayacucho

Cuzco

Collao (Puno)

Northern Bolivian (Apolo)

Quechua IIC:

Ecuadorian Quechua

(Highlands and Oriente)

Chachapoyas

San Martín (Lamas)

Quechua IIB:

Huaylas-Conchucos

Alto Pativilca–

Alto Marañón–

Alto Huallaga

Ya r u

Jauja-Huanca

Huangáscar-Topará

Quechua I:

Quechua IIA:

Ferreñafe (Cañaris)

Cajamarca

Lincha

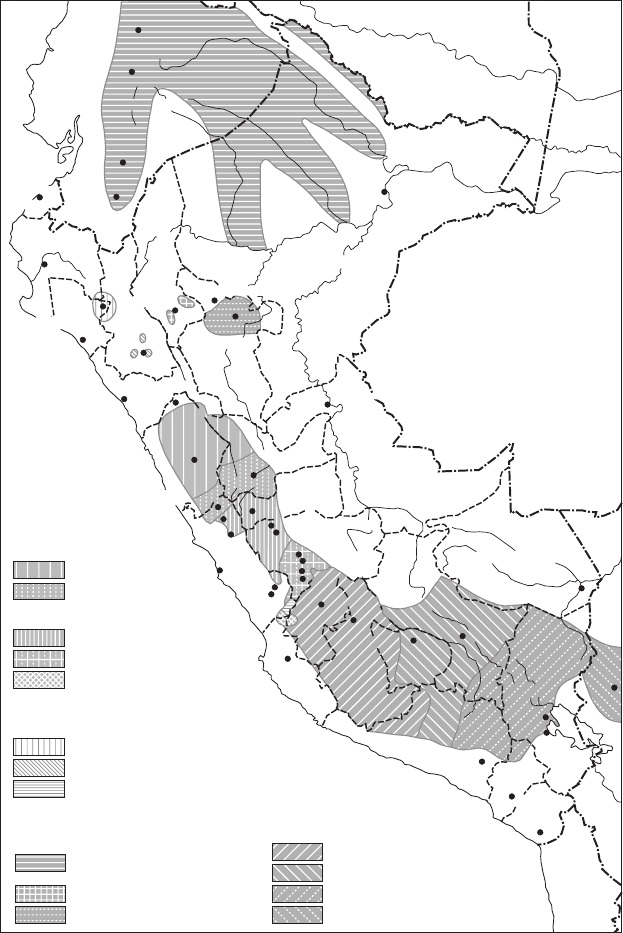

Map 5 Approximate distribution of Quechua dialects in Peru and adjacent areas

3.2 The Quechuan language family 185

theoretical interest, due to the complex character of the phonological and morphological

facts and the often subtle formal and semantic shifts that separate the numerous dialects.

Dialect differences appear to function as markers of local or regional identity.

From a genetic and classificatory point of view, the Quechua dialects must be divided

into two main branches. One of them has been termed Quechua B (in Parker 1963),

Quechua I (in Torero 1964), or Central Quechua (Mannheim 1985a, Landerman 1994).

It occupies a compact and continuous area in the central Peruvian highlands, including

the Andean parts of the departments of Ancash, Hu´anuco, Jun´ın and Pasco (with the

exception of the province of Pallasca in northern Ancash), some of the Andean parts of

the department of Lima and a few districts in the departments of Huancavelica, Ica and

La Libertad.

Quechua B or I constitutes a heavily fragmented dialect complex with a number of

clear common features. A more refined subdivision into five subgroups is proposed in

Torero (1974). These subgroups are the following:

a. Huaylas–Conchucos consists of the Quechua-speaking areas of Ancash,

except for the province of Bolognesi in the south; it also includes the

provinces of Mara˜n´on and Huamal´ıes in the north of the department of

Hu´anuco and a small Quechua-speaking pocket near Urpay in the depart-

ment of La Libertad.

b. Alto Pativilca–Alto Mara˜n´on–Alto Huallaga includes the remainder of the

Quechua-speaking area of the department of Hu´anuco; the province of

Bolognesi in Ancash; and a part of the province of Cajatambo, as well

as the district of Ambar (province of Huaura), both in the department of

Lima.

c. Yaru includes the Andean sector of the department of Pasco; the northern

sector of the Quechua-speaking area in the department of Jun´ın (provinces

of Jun´ın, Yauli and Tarma); parts of the provinces of Cajatambo, Huaura

and Oy´on in the department of Lima; the districts Alis and Tomas in the

province of Yauyos, also in the department of Lima.

d. Jauja–Huanca includes the remainder of the Quechua-speaking area of

Jun´ın; and the district of Cacra in the province of Yauyos (Lima).

e. Huang´ascar–Topar´a includes the districts of Huang´ascar, Chocos and

Az´angaro in the province of Yauyos (Lima); the district Chav´ın de Topar´a

in the province of Chincha (Ica); the districts of Tantar´a, Aurahu´a and

Arma in the province of Castrovirreyna (Huancavelica).

The second branch, Quechua A or II, has a much wider extension and comprises all the

remaining varieties of Quechua located both to the north and to the south of the central

Peruvian dialect area. It also includes the Quechua dialects spoken in the Amazonian

lowlands to the east of the Andean cordilleras and, most probably, the Quechua dialect(s)

186 3 The Inca Sphere

once spoken on the central Peruvian coast between Huaura and Ca˜nete. The different

‘general languages’ all belonged to this group.

Speaking in general terms, the twofold classifications originally proposed by Parker

and Torero are almost identical. However, Torero’s classification includes a further

subdivision of Quechua II into the three subgroups Quechua IIA, Quechua IIB and

Quechua IIC.

9

Although very closely related, both Quechua IIB and Quechua IIC ex-

hibit distinct characteristics that make it possible to decide whether a particular dialect

is to be included or not in either subgroup. The case of Quechua IIA is more problem-

atic. It was meant to include two dialect areas in northern Peru in the departments of

Cajamarca (provinces of Cajamarca and Bambamarca) and Lambayeque (mainly in the

districts of Ca˜naris and Incahuasi in the cordilleran sector of the province of Ferre˜nafe),

as well as a number of village dialects in the department of Lima in central Peru. These

are the dialects of Laraos, Lincha, Made´an and Vi˜nac in the province of Yauyos, the

southeasternmost part of the department of Lima, and, further north, the dialect spoken

in the community of Pacaraos in the higher reaches of the Chancay river valley (province

of Huaral).

The dialects that were assigned to Quechua IIA occupy an intermediate position

between Quechua I and the rest of Quechua II. Taylor (1979a) gives it the status of a

separate division, calling it Quechua III. The difficulty with the classificatory status of

Quechua IIA is that it does not constitute a unity. The northern dialects of Cajamarca

and Ferre˜nafe share characteristics of both Quechua IIB and Quechua I. The dialects of

Yauyos hold a similar position between Quechua IIC and Quechua I. Pacaraos has so

much in common with the Quechua I dialects, by which it is partly surrounded, that some

authors prefer to associate it with Quechua I (Parker 1969d: 191–2). Alternatively, it

could be considered as a separate branch of the Quechuan family on a par with Quechua I

and II. The resemblances between Pacaraos Quechua and Quechua II, which motivated

its initial classification as a Quechua IIA dialect, should be attributed to morphological

and lexical conservatism rather than to its alleged membership of that group (cf. Adelaar

1984).

Quechua IIB includes the dialects of the Ecuadorian highlands and oriente (the east-

ern lowlands); the Colombian Quechua dialect usually called Inga or Ingano (Caquet´a,

Nari˜no, Putumayo); the dialects spoken in the Peruvian department of Loreto in the

Amazonian lowlands (which are, in fact, extensions of the varieties spoken in the

Amazonian region of Ecuador); the Lamista dialect spoken in the area of Lamas (depart-

ment of San Mart´ın, Peru); and that of Chachapoyas and Luya (department of Amazonas,

9

Henceforth, we shall refer to the dialect branches of the Quechua family by means of the termi-

nology of Torero’s classification (Quechua I, II), because it allows for a further subdivision of the

Quechua II branch.

3.2 The Quechuan language family 187

Peru). Some extinct varieties are also assignable to Quechua IIB: both the ‘coastal’ dialect

described by Santo Tom´as in 1560 and the variety of Quechua used in the aforementioned

manuscript from Huarochir´ı (of 1608) have lexical and morphological characteristics

that are strongly suggestive of a Quechua IIB affiliation. Ecuadorian and Colombian

Quechua have undergone a profound transformation affecting much of the complex

morphology inherited from Proto-Quechua, which has been preserved in the more con-

servative dialects of Peru and Bolivia. Most conspicuous for this process are the loss

of the personal reference markers indicating possession with substantives and of those

specifying the patient in verbs. The relatively recent character of the morphological

transformation that took place in the Ecuadorian–Columbian branch of Quechua IIB

can be deduced from the fact that not all varieties belonging to it were affected in an

equally radical way. An example of such conservatism is the dialect spoken along the

Pastaza river in the department of Loreto in Peru (Landerman 1973).

Quechua IIC presently includes all the dialects situated to the southeast of a linguistic

boundary which coincides with the administrative division between the departments of

Jun´ın and Huancavelica in central Peru. It comprises the best-known and most pres-

tigious dialects outside Ecuador, which are used by substantial numbers of speakers:

Ayacucho Quechua, Cuzco Quechua and Bolivian Quechua. The Argentinian dialect

of Santiago del Estero and the extinct variety of Catamarca and La Rioja in the same

country also belong to the Quechua IIC branch. Ayacucho Quechua covers the Andean

parts of the departments of Ayacucho and Huancavelica, as well as the western and

northwestern sections of Apurimac (provinces of Andahuaylas and Chincheros) and

Arequipa (provinces of Caravel´ı, Condesuyos and La Uni´on). Cuzco Quechua includes

the Andean regions of the departments of Cuzco, as well as parts of Apurimac (provinces

of Abancay, Antabamba, Cotabambas, Grau and Aymaraes), Arequipa (provinces of

Arequipa, Castilla, Caylloma and Condesuyos), Moquegua (province of S´anchez Cerro)

and Puno (provinces of Az´angaro, Carabaya, Huancan´e, Lampa, Melgar, Puno, Sandia,

San Antonio de Putina and San Rom´an).

10

The traditional division between Ayacucho Quechua and Cuzco Quechua has to do

with the existence of glottalised (ejective) and aspirated consonants, which do occur

in the latter but not in the former. However, the Cuzco Quechua dialect area is far

from homogeneous. The dialectal variants of Arequipa and Puno exhibit cases of lexical

and morphological borrowing from Aymara not found in the Cuzco variant. The central

Apurimac variant of Cuzco Quechua (provinces of Abancay, Antabamba and Aymaraes)

maintains several phonological and lexical features connecting it to Ayacucho Quechua

(Landerman 1994; Chirinos Rivera 1998).

10

The data concerning the distribution by provinces of Ayacucho and Cuzco Quechua in Apurimac,

Arequipa and Puno are mainly from Chirinos Rivera (1998), who also recognises a further

division between Cuzco and Collavino (Puno) Quechua.

188 3 The Inca Sphere

Bolivian Quechua is spoken in the Bolivian highlands (departments of Cochabamba,

Sucre and Potos´ı, parts of Oruro and most of La Paz north of Lake Titicaca), and in ad-

jacent areas of Argentina (provinces of Jujuy and Salta). Together with Cuzco Quechua,

it is often referred to as a single Cuzco–Bolivian dialect because both varieties share the

contrast of plain, glottalised and aspirated stops and affricates. From a morphological

point of view, however, Bolivian Quechua is very different from Cuzco Quechua. It has

been reported that the Quechua spoken on the northern Andean slopes in the department

of La Paz is phonologically more conservative than both Cuzco Quechua and the rest of

Bolivian Quechua (Stark 1985b). Hence, a distinction is made between a northern and

a southern Bolivian variant.

Larra´ın Barros (1991) mentions the presence of Quechua speakers in the Chilean

province of Antofagasta, in the Atacama desert oases of Ayquina, Cupo, Toconce and

Turi. There are no specific data on this dialect, but it is likely to be an extension of the

Bolivian variety of Quechua.

The Quechua-speaking area of Santiago del Estero in Argentina is not contiguous with

Bolivian Quechua. It is mainly concentrated in the hot lowlands bordering the banks of

the Salado river. The verbal morphology of Santiague˜no Quechua shares a number of

very specific innovations with Bolivian Quechua. Phonologically, however, Santiague˜no

Quechua is rather different from Bolivian Quechua. Unlike the latter, it lacks glottalised

and aspirated consonants. It is reminiscent of the northern Peruvian dialects because it

preserves a remnant of the s–ˇs distinction, which otherwise is not found in Quechua IIC

(see section 3.2.5). The characteristics of Santiague˜no Quechua were almost certainly

derived from different dialectal sources (cf. Adelaar 1995b).

The Quechua dialects are best viewed as a ‘dialect chain’ in the definition provided

by Kaufman (1990). However, the opposition between the two main groups Quechua

I and Quechua II is more fundamental. It seems to reflect an initial split at the level

of Proto-Quechua. The distinction between the two groups primarily rests on lexi-

cal and morphological facts. Phonological diversity is rampant in both groups, and

much of it can only be interpreted as a result of developments posterior to the initial

split.

Although the lexical differences between Quechua I and Quechua II are quite real, their

distribution seldom reflects a clear-cut division between the two groups. For instance, the

Quechua II verb root for ‘to go’ ri- corresponds to Quechua I aywa-. However, Quechua

I Huanca, which borders on Quechua IIC Ayacucho, has li-, a reflex of *ri-. It may be

the result of dialect interference, but it can also be explained by assuming an innovative

substitution of aywa- for *ri- that would have occurred in Quechua I without reaching

the outlying Huanca area.

11

11

The verb aywa-isreminiscent of Aymara aywi- ‘to go (several)’.

3.2 The Quechuan language family 189

Morphological arguments come the closest to providing unequivocal criteria for as-

signing a dialect to either one of the two subgroups. Morphological criteria tend to occur

in bundles, although there is never a full coincidence. Best known among them is the

shape of the first-person marker for subject and possessor. It is -y (nominal and verbal)

or -ni (exclusively verbal) in most of Quechua II; e.g. waska-y ‘my rope’, wata-y-man

‘I could tie (it)’, wata-ni ‘I tie (it)’. In Quechua I, it is marked both on verbs and on

nouns by the lengthening of the preceding vowel (symbolised as -:); e.g. waska-: ‘my

rope’, wata-:-man ‘I could tie (it)’, wata-: ‘I tie (it)’. The dialect of Pacaraos (cf. section

3.2.9) has its own distinctive first-person marker -´y.Itconsists of a segment -y that

attracts stress to the preceding vowel when it occurs in word-final position. Landerman

(1978) reports that some transitional Quechua IIA dialects, such as Lincha, combine the

markers -´y (for nouns) and -ni (for verbs).

12

Some further morphological criteria that can contribute to distinguishing between

Quechua I (QI) and Quechua II (QII) are:

a. The shape of the marker referring to identical subjects in the switch-

reference system (cf. section 3.2.6) is -r (or its reflex) in Quechua I. It is

-ˇspa (or its reflex) in Quechua II. Huallaga Quechua (QI) has both forms,

-r being used alone and -ˇspa with optional personal reference markers

(Weber 1989). Pacaraos Quechua (cf. section 3.2.9) has -ˇspa, although its

morphology follows Quechua I in most other respects.

b. The shape of the locative case marker is -pi (or its reflex) in most of

Quechua II. It is -ˇc

.

aw

13

(or its reflex) in Quechua I and in Pacaraos

Quechua. The element ˇc

.

aw is obviously related to the root *ˇc

.

awpi ‘mid-

dle’, ‘centre’, of which reflexes are found in both dialect branches. It is

also found in Quechua II punˇcaw (< *punˇc

.

aw) ‘day’ (cf. QI Huanca pun

‘day’, QI northern Jun´ın hukpun ‘the other day’).

c. The shape of the ablative case marker is -manta (or its reflex) in most of

Quechua II. In Quechua I, we either find -pita,orreflexes of *-piq(ta).

Pacaraos Quechua has both -piq and -piqta in free variation.

d. The shape of the first-person patient marker in verbs is -wa-inmost of

Quechua II. It is -ma(:)- in Quechua I and in some Quechua IIA dialects

(Ferre˜nafe, Pacaraos).

e. In most Quechua II dialects, the verbal and nominal personal reference

markers, which are used for subject, object and possessor, are pluralised

12

There are several conflicting hypotheses concerning the reconstruction of the Proto-Quechua

first-person marker (Torero 1964; Proulx 1969; Landerman 1978; Cerr´on-Palomino 1979; Taylor

1979a; Adelaar 1984).

13

The symbol ˇc

.

refers to a voiceless retroflex affricate; its non-retroflex alveo-palatal counterpart

is indicated as ˇc (see section 3.2.5).

190 3 The Inca Sphere

externally, by means of suffixes that must follow these markers. Quechua I

and Pacaraos lack a morphological means to indicate plurality of possessor

with substantives. Plurality of subject in verbs (or, occasionally, plurality

of object) is indicated internally, by means of suffixes that have their lo-

cus between the verb root and the personal reference markers. In several

dialects the choice of plural markers depends on their co-occurrence with

aspect markers. Some combinations of aspect and plural are indicated by

fused (portmanteau) markers.

f. Quechua I dialects and Pacaraos Quechua have productive verbal deriva-

tional suffixes that mark the direction of a movement, viz. -rku- ‘upward

movement’ and -rpu- ‘downward movement’. A fossilised -rqu- (or its

reflex) is found both in Quechua I and Quechua II dialects with a recon-

structed meaning ‘outward movement’ (e.g. in QI yarqu- ‘to leave’, QI/II

hurqu- ‘to take out’). Likewise, the meaning of *-yku- has been recon-

structed as ‘inward movement’. Reflexes of *-rqu- and *-yku- are found

throughout the Quechua dialects, but with modified meanings.

g. Many Quechua dialects distinguish two past tenses. Whereas one refers to

any event in the past, the other has the connotation of surprise or previous

lack of knowledge on the part of the speaker. It is marked by reflexes of

*-n

y

aq in Quechua I and in Pacaraos, and by reflexes of *-ˇsqa in most of

Quechua II (see further section 3.2.6).

h. The one important phonological distinction that separates Quechua I (and

Pacaraos) from Quechua II is the treatment of a sequence of low vowels

separated by a palatal glide, viz. *-aya-. It has been retained in most of

Quechua II, whereas in the former dialects it became -a:-. As a result, a

phonemic length distinction exists in the Quechua I dialects which has ac-

quired further applications, including cases of long high vowels (-i:-, -u:-).

It has been assumed that Proto-Quechua had embryonic vowel quantity

in lexical roots, such as pu:ka- ‘to blow’, and in the first-person marker

(Torero 1964). However, if it is true – as seems to be the case – that the QI

first-person marker (-a:, -i:, -u:) originated from stressed word-final *-´ay,

*-´ıy, *-´uy (as in present-day Pacaraos Quechua), this would further reduce

the number of long vowels to be reconstructed for Proto-Quechua (Adelaar

1984).

14

The existence of distinctive vowel length is now the most salient

characteristic of Quechua I as opposed to Quechua IIB and Quechua IIC,

where it does not occur.

14

It should be emphasised that the reconstruction proposed here is by no means generally

accepted.

3.2 The Quechuan language family 191

Although the validity of the initial subdivision of the Quechuan family into two main

branches has been questioned on phonological grounds (Mannheim 1991: 176), it will

be clear from the above that the morphological and lexical evidence favouring such

adivision is abundant. Nevertheless, it may not be possible to accommodate all the

existing Quechua dialects into either one of the two branches.

3.2.4 Quechua studies

Quechua is among the Amerindian languages that have receivedmajor scholarly attention

from the beginning of Spanish rule in Peru until the present century (see also chapter 1).

In the context of the present work we can do no more than highlight some of the most

important writings on Quechua. For a survey of the older literature on Quechua one can

consult Rivet and de Cr´equi-Montfort’s extensive Bibliographie des langues aymar´aet

kiˇcua (1951–6).

Spanish clerical grammarians established the tradition of Quechua studies. However

impressive their pioneering work may have been from the start, its value has greatly

increased now that modern field data on Quechua have become available. Language is the

one element in Andean culture that has remained relatively stable. The confrontation of

sixteenth- and seventeenth-century grammars and dictionaries with phonologically and

semantically more accurate modern material permits a much more precise interpretation

than hitherto possible.

The Dominican Domingo de Santo Tom´as was among the leading figures of the

first decades of the Spanish administration. He often sided with the Indians in cases

of mistreatment and oppression by European colonists, and provided Las Casas with

material for his famous polemics (Duviols 1971: 88). Santo Tom´as’s grammar and

lexicon of the general language of Peru (1560a, b) provide a description of Quechua older

than that of many European languages. From a dialect-geographic point of view, Santo

Tom ´as draws from heterogeneous sources. He describes an archaic Quechua, probably

identical to the extinct coastal dialect or to the language of the Inca administration,

larded with elements taken from central Peruvian dialects. The first Quechua study to

appear after Santo Tom´as is an anonymous work published by Antonio Ricardo in 1586.

It is best known through a modern edition of Aguilar P´aez (1970).

A landmark in the Spanish grammar tradition in relation to Quechua is Diego Gonz´alez

Holgu´ın’s Gram´atica y arte nueva de la lengua general de todo el Per´u llamada lengua

qquichua o lengua del Inca (New Grammar of the General Language of all of Peru, called

the Qquichua Language or Language of the Inca) of 1607, followed by an extensive

dictionary (1608) by the same author. Both works describe the ancestor of present-day

Cuzco Quechua, thus reflecting a shift in the centre of gravity of what was left of Inca

society to the ancient Inca capital. Together with Bertonio’s grammar and dictionary

of the Aymara language (cf. section 3.3), Gonz´alez Holgu´ın’s study of the Quechua

192 3 The Inca Sphere

language has stood as a model for much later work on Quechua and the other Andean

languages.

During the eighteenth century the colonial grammar tradition in relation to Quechua

became less prominent, although there are some notable exceptions dealing with

Ecuadorian (e.g. Velasco 1787).

After the Andean republics became independent, many studies of the Inca language

came from the outside. Important nineteenth-century contributions to the study of

Quechua were made by a Swiss, von Tschudi (1853), and, above all, by the German

Middendorf (1890a, b, c, 1891a). Middendorf’s Die einheimischen Sprachen Perus (The

Indigenous Languages of Peru) contains a dictionary and grammar of Cuzco Quechua,

an edition of the play Ollantay and a collection of poetry. Luis Cordero, one of Ecuador’s

former presidents, published a Quichua–Spanish dictionary in 1892.

Among the Quechua studies of the first half of the twentieth century figures an interest-

ing collection of animal fables in the dialect of Tarma (Vienrich 1906). Markham (1911:

230–4) published a Quechua myth in translation, a fragment of the now well-known

Huarochir´ı document guarded in the Spanish National Library in Madrid. A series of

texts in different Peruvian dialects by Farf´an (1947–51) and an elaborate dictionary of

Cuzco Quechua (Lira 1941) also deserve a mention.

In the initial phase of the dialectological tradition which developed in the 1960s,

Parker’s work, published in a preliminary form (Parker 1969–71), comprises a great

deal of reconstruction of both the A and B branches of Quechua and, above all, a useful

Proto-Quechua lexicon (Parker 1969c). Torero published several studies linking the

results of his dialectological findings to Andean ethnohistory (1968, 1970, 1974, 1984).

Dialectological studies of a regional dimension were carried out by Nardi (1962) for

Argentina, by Cerr´on-Palomino (1977a) for the Huanca area, by Taylor (1984) for the

Yauyos region, and by Carpenter (1982) and Stark (1985a) for Ecuador.

Other dialectological work concerns particular morphemes or morphological cate-

gories, exemplified by a series of articles focusing on the personal reference system

(Taylor 1979a; Cerr´on-Palomino 1987c; Weber 1987b: 51–75). The grammatical char-

acteristics of the language of the Huarochir´ı manuscript constitute another fruitful area

of interest (e.g. Dedenbach 1994). For work dealing with syntactic issues in particu-

lar dialects, see, for instance, W¨olck (1972) for Ayacucho Quechua, Muysken (1977)

for Ecuadorian Quechua, Weber (1983) for Hu´anuco Quechua, Hermon (1985) for

Ecuadorian and Ancash Quechua, Lefebvre and Muysken (1988) for Cuzco Quechua,

and Van de Kerke (1996) for Bolivian Quechua. Examples of work dealing with phono-

logical issues are Cerr´on-Palomino (1973a, b, 1977b, 1989a), Escribens Trisano (1977),

Sol´ıs and Esquivel (1979) and Weber and Landerman (1985). It goes without saying that

the above enumeration is by no means complete.

The Quechua linguistic family is particularly rich in overall descriptions, the earliest

modern one being Parker’s grammar of the Ayacucho dialect. It appeared first in Spanish

3.2 The Quechuan language family 193

(Parker 1965), then in English with a hitherto unsurpassed dictionary supplement (Parker

1969a). Almost contemporaneous with the former is a concise grammatical description

of the Quechua I dialect of Llata in the province of Huamal´ıes in the northern part of

the department of Hu´anuco (Sol´a 1967). The basis for a description of Ancash Quechua

(QI) was laid by Swisshelm of the Benedictine congregation at Huaraz (Swisshelm

1971, 1972, 1974). Partial descriptions of Amazonas Quechua (QIIB), as spoken in

the community of Olto (Chachapoyas), and of the dialect of the Pastaza river, which is

located in Peru but belongs to the Ecuadorian branch of Quechua IIB, were provided by

Taylor (1975, 1994) and by Landerman (1973), respectively.

For Bolivian Quechua, the earliest generation of modern descriptive work includes

Lastra’s study of Cochabamba Quechua (1968). For Colombia, we could add Levinsohn’s

description of Inga (1976), written in a rather technical tagmemic framework. The

Argentinian Santiago del Estero dialect has been treated in a traditional way by Bravo

(1956).

Of particular importance to Quechua studies is the year 1976, it being the date of pub-

lication of a series of six grammars and dictionaries commissioned by the Peruvian gov-

ernment (Cerr´on-Palomino 1976a, b; Coombs, Coombs and Weber 1976; Cusihuaman

1976a, b; Park, Weber and Cenepo 1976; Parker 1976; Parker and Ch´avez 1976; Quesada

Castillo 1976a, b; Soto Ruiz 1976a, b). These accessible and easily available works deal

with six dialect varieties selected to become regional standards after the officialisation of

Quechua in 1975: Ancash–Huaylas (QI), Ayacucho–Chanca (QIIC), Cajamarca–Ca˜naris

(QIIA), Cuzco–Collao (QIIC), Jun´ın–Huanca (QI) and San Mart´ın (QIIB). These de-

scriptions were designed to serve a normative purpose, and several of them have a

polylectal character. Although the initiative is praiseworthy, one should add that some

of the descriptions show the signs of a hasty completion. For highly interesting dialects

such as Cajamarca, Cuzco and Huanca, they represent a half-way resting-place, rather

than a terminus. A comparative study of Quechua morphology (W¨olck 1987) was based

on the data provided by these six descriptions.

Grammatical descriptions of Peruvian dialects posterior to the 1976 series of Peruvian

reference grammars are Adelaar (1977) for the dialects of Tarma and San Pedro de

Cajas (QI Yaru) and Weber (1989) for Hu´anuco (QI Alto Pativilca–Alto Mara˜n´on–Alto

Huallaga). One may add Taylor (1982a, b, 1994) on Ferre˜nafe Quechua (QIIA) and

Adelaar (1982, 1986a) on Pacaraos Quechua. For Bolivia and Ecuador, descriptive work

includes a grammar of Bolivian Quechua by Herrero and S´anchez de Lozada (1978) and

a reference grammar of the Ecuadorian Imbabura dialect (Cole 1982).

One of the most widely used Quechua–Spanish dictionaries is Lara (1971). Although

it does not contain an explicit indication of the geographic provenance of the items

included, it is based mainly on Bolivian and Cuzco Quechua. It is remarkably useful

when reading and translating Quechua texts. A very extensive dictionary (Weber et al.

1998) deals with the lexicon of Hu´anuco Quechua.