Yamaguchi H. Engineering Fluid Mechanics (Fluid Mechanics and Its Applications)

Подождите немного. Документ загружается.

5.5 Oblique Shock Wave

E

tan

1

t

n

u

u

and

TE

tan

2

t

n

u

u

(5.5.6)

By defining

111

auM / , we can write

E

sin

111

Mau

n

/ since typically

E

sin

11

uu

n

. Thus, the normal shock relationship from Eq. (5.5.5) can be

written for the oblique shock relationship by replacing

1

M in Eq. (5.4.5)

with

E

sin

1

M , which gives

2sin1

sin1

22

1

22

1

1

2

2

1

E

E

U

U

Mk

Mk

u

u

n

n

(5.5.7)

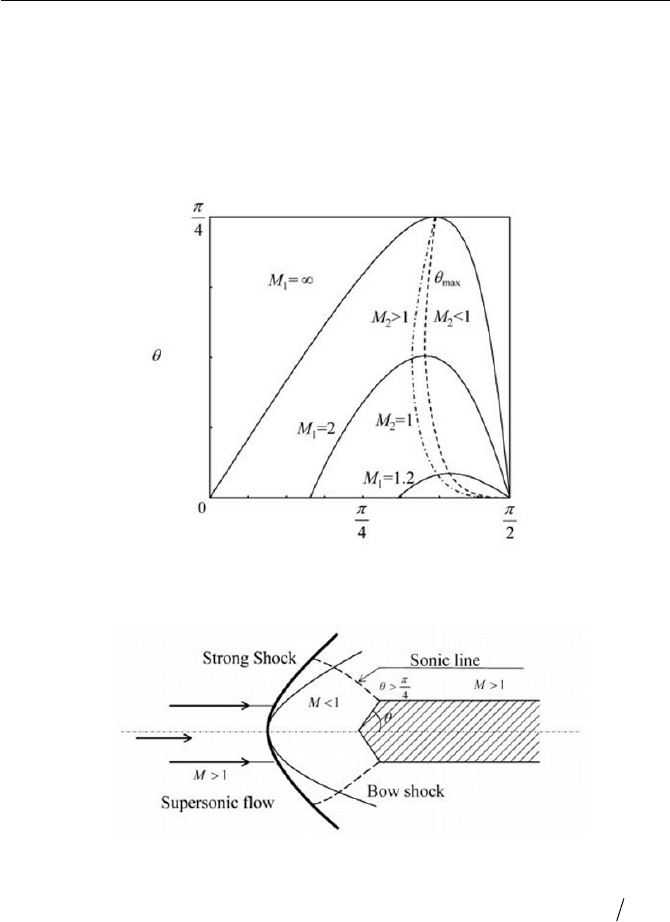

Perhaps it is worth taking a moment to consider the relationship be-

tween the shock inclination angle

E

and the wedge angle

T

. Substituting

the relations from Eq. (5.5.6) into Eq. (5.5.7), we can derive the following

relationship between

E

and

T

E

E

E

TE

22

1

22

1

sin1

2sin1

tan

tan

Mk

Mk

(5.5.8)

By solving Eq. (5.5.8) for

T

, we can write the angle

T

as

E

E

E

T

cot

22cos

1sin2

tan

2

1

22

1

kM

M

(5.5.9)

Depending on

1

M , Eq. (5.5.9) shows that

T

will be zero for

E

, equal to

either

2

S

or

1

1

1sin M/

, or somewhere within this range, noting that

there is a maximum of

T

. Figure 5.12 is a plot of

T

versus

E

for a given

1

M , where the dashed line is a curve for max

T

. Figure 5.12 indicates that

there are two possible solutions of

E

for

T

4

S

T

. In practice it is ob-

served that the solution (to a weak shock) occurs and has a weaker discon-

tinuity, with a remainder of 1

2

!M (except for in a region between the

lines 1

2

M and

max

T

). That is, two solutions are derived from the jump

conditions, which are in effect characterized by different shock inclinations

angles and shock intensities. The solutions are known as the weak and

strong solutions. Phenomenologically the strong solution indicates a flow

which is subsonic downstream from the shock with

2

max

S

E

T

,

253

5 Compressible Flow

whereas the weak solution describes a flow which is supersonic down-

stream from the shock in

E

less than the line of 1

2

M . With a symmet-

rical slender wedge,

1

u is parallel to the surface of the wedge with an an-

gle of

T

, so that when

1

M is specified, the shock inclination angle

E

will

be calculated from Eq. (5.5.9).

Fig. 5.12

E

T

p

plot for an oblique shock

Fig. 5.13 Detached shock wave

It is interesting to see the flow phenomena if

T

is greater than

4ʌ

. It

appears that neither an oblique shock nor a normal shock is possible and it

is observed from experiment that the shock becomes detached. That is to

say, the shock curves around the wedge are not touching the wedge, as

schematically displayed in Fig. 5.13. The phenomenon also occurs with a

blunt body. There are some regions after the curved shock wave, called the

bow shock, as shown in Fig. 5.13. The dotted line, which corresponds to

254

Exercise

1

M

, is called the sonic line and divides the two regions of supersonic

and subsonic flow. It is found that the drag on a blunt body (or higher de-

flection angled wedge) is higher than that of a slender body when the body

is traveling with supersonic speed. This is due to the shock wave being de-

tached, and to reduce the drag it is advantageous to adopt a small nose an-

gle (wedge angle) for supersonic crafts so that the oblique shock may be

formed on the body.

Exercise

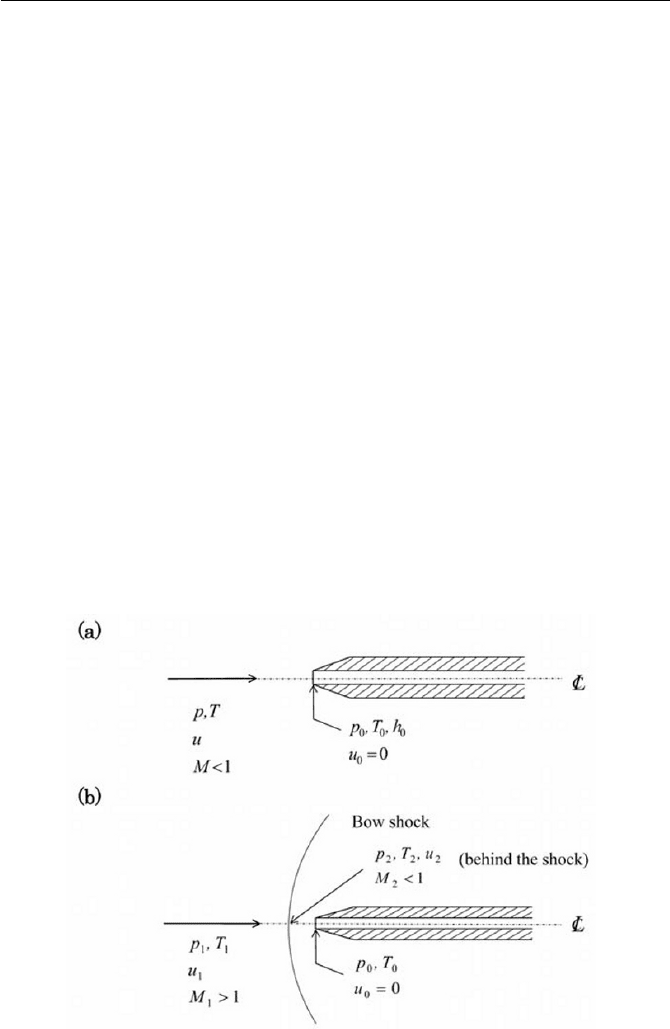

Exercise 5.1 The Compressibility Factor

In an isentropic flow through a channel from a reservoir, the pressure in

the reservoir is such that the velocity of flow is identically zero

㧚In con-

trast to the reservoir, when an isotropic flow is brought to rest at any point

of a flow field, the pressure with zero velocity can be obtained with the

same treatment as the case of a reservoir. The stagnation pressure is such

that a flow is brought to rest. We will now consider the stagnation pressure

0

p

for an isentropic flow in terms of the Mach number.

Fig. 5.14 The stagnation pressure; Pitot tube configuration

255

5 Compressible Flow

The typical application of such a flow is found by measuring its velocity

via the Pitot tube, as depicted in Fig. 5.14(a) and (b). Show the effect of

Mach number in measuring the stagnation pressure, and thus the velocity

of flow for an ideal gas.

Ans.

Let consider the energy equation of Eq. (5.2.13) between the upstream

and the stagnation, as indicated in Fig. 5.14(a)

hhuu

0

2

0

2

2

1

(1)

For an ideal gas we may write the enthalpy with the aid of the relations

Tch

p

and

00

Tch

p

. Also using

auM

and

1 kkRc

p

, we can

reduce Eq. (1) to the following form, by setting 0

0

ou

2

0

2

1

1

M

k

T

T

(2)

For the isentropic flow, we have a thermodynamic relation

1

00

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

k

k

T

T

p

p

(3)

In combination with Eqs. (2) and (3), the stagnation pressure

0

p is thus

expressed by

1

2

0

2

1

1

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

k

k

M

k

p

p

(4)

If this equation is expressed with a binomial expansion for the Mach num-

ber, we have

642

0

48

2

82

1

M

kk

M

k

M

k

p

p

(5)

and

¿

¾

½

¯

®

4

22

0

24

2

4

1

2

M

kMpkM

pp

(6)

It will prove useful to write the leading term of the right hand of Eq. (6) as

256

Exercise

22

2

2

2

1

2

1

22

uu

RT

p

kRT

u

k

ppkM

U

Thus, Eq. (6) becomes

c

M

kM

u

pp

D

U

4

2

2

0

24

2

4

1

2

1

(7)

The right hand side of Eq. (7) can be represented by

c

D

, which is called

the compressibility factor. For example, in the case of air

4.1 k

, it is cal-

culated that 2761

.

c

D

at 1

M

and in a lower Mach number case, we

can say that 0221

.

c

D

at 3.0 M . Thus, for measuring the velocity by a

Pitot tube, we can write the Eq. (7) as

2

1

0

2

c

pp

u

D

U

(8)

The actual velocity measured by a Pitot tube for a flow of 30

. M is ap-

proximately %1.1 less than that of incompressible flow measurement.

In supersonic flow, however, a detached shock wave may be formed

ahead of a Pitot tube as shown in Fig. 5.14(b). Along the center line, the re-

lationship across a normal shock can be applied that are found in Eqs.

(5.4.18) and (5.4.6), written as

12

21

2

1

2

1

2

2

kkM

Mk

M and

1

12

2

1

1

2

k

kkM

p

p

(9)

The isentropic relation of Eq. (4) can be used between the point of after

shock to the stagnation point as indicated in Fig. 5.14(b), which is given as

1

2

2

2

0

2

1

1

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

k

k

M

k

p

p

(10)

With Eqs. (9) and (10), eliminating

2

M and

2

p , we can derive the follow-

ing relationship between the upstream and the stagnation point

257

5 Compressible Flow

1

1

2

1

1

2

1

0

12

1

2

°

°

°

¿

°

°

°

¾

½

°

°

°

¯

°

°

°

®

¸

¸

¹

·

¨

¨

©

§

k

k

k

kkM

k

M

p

p

(11)

Equation (11) relates the stagnation pressure for a supersonic flow and the

formula is called the Rayleigh’s Pitot-tube relation.

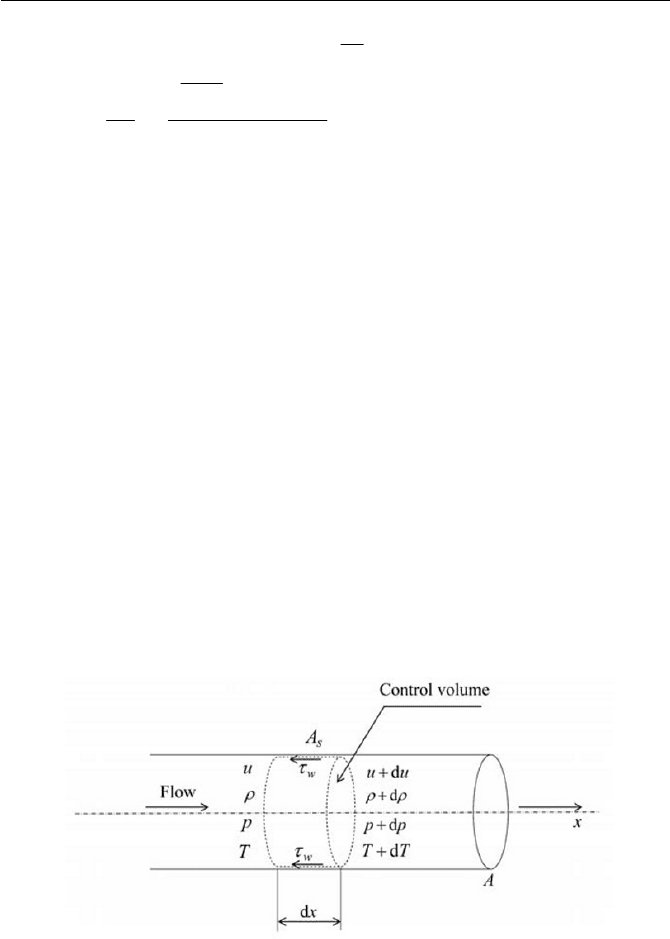

Exercise 5.2 Fanno-line Flow Relations and Chocking

Consider a flow of ideal gas in a horizontal tube of constant cross-section.

The flow in the tube is assumed adiabatic, but with friction, i.e. the exis-

tence of wall shear stress. Derive Fanno-line flow relations and discuss the

possibility of chocking condition.

Ans.

Let denote A as the cross-section area and dx as a small increment of

x

as indicated in Fig. 5.15, where the control volume is defined by dotted

line together with flow and thermodynamic parameters. For the control

volume, we will apply (i) the mass continuity, (ii) the momentum and (iii)

the energy equations as described below.

Fig. 5.15 Fanno-line flow,

w

W

t

the wall shear stress

258

Exercise

.const uA

U

(1)

For A constant, we can write Eq. (1) in a differential form as

0

u

dud

U

U

(2)

(ii) Momentum equation

The momentum balance of the control volume is

>@

sw

AAdpppAuduuuA

W

U

(3)

where

w

W

is the wall shear stress and

s

A

is the wall surface area of the

control volume.

w

W

can be defined, using the friction factor

f

c , as

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

2

2

1

uc

fw

UW

(4)

We can assume that

f

c

is kept constant along the channel. It is reassuring

to know that the constant of

f

c is justified since it is kept around

00300040

.~.

f

c for the Reynolds number

69

1010 ~ , although

f

c is a

function of the Reynolds number, the Mach number and surface roughness

H

(RMS) of tube wall,

DRecc

ff

H

,, M . In a case of circular tube of

diameter

D

, i.e.

DdxA

s

S

, Eq. (1) can be rearranged as follows

0

4

2

1

2

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

dx

D

c

p

dp

kM

u

du

f

(5)

where for

2222

kpMaMRTpu

U

is used and, a is the speed of

sound.

(iii) Energy equation

The energy equation of an ideal gas with the enthalpy defined as

Tch

p

is written from Eq. (5.2.13) as

0

dTcudu

p

(6)

By dividing the both sides by

Tc

p

and recognizing

1 kkRc

p

, we

can obtain

(i) Mass continuity equation

259

5 Compressible Flow

01

2

u

du

Mk

T

dT

(7)

It should be kept in mind that, as in Eqs. (1) to (7), there is no particular

thermodynamic process mentioned for the control volume, but with the

adiabatic condition to the control volume being assumed, we can assume

there is no heat transfer to or from the control volume.

(iv) Entropy change and Mach number

The equation of state for an ideal gas is written as

RTp

U

, and it’s

differential form is

T

dTd

p

dp

U

U

(8)

The entropy change of the control volume is, from the second law of ther-

modynamics

U

U

d

R

T

dT

cds

v

U

U

d

R

T

dT

k

R

1

(9)

It is noted again that the adiabatic condition to the control volume does not

directly mean it is isentropic, since we are considering the friction of flow.

From the definition of the Mach number

kRTuM , a differential form

is

T

dT

u

du

M

dM

2

1

(10)

Now we are able to reduce the Fanno-line of flow relations in terms of

the Mach number, using Eqs. (1) to (10). To begin with, eliminating

TdT

as in Eqs. (7) and (10) and by combining them with Eq. (2), we can obtain

U

U

d

dM

Mk

k

Mu

du

¿

¾

½

¯

®

2

22

21

11

2

1

(11)

Equation (11) is substituted into Eq. (7) and we have the relationship that

follows

260

Exercise

dM

Mk

Mk

MT

dT

¿

¾

½

¯

®

21

121

2

2

(12)

In the same manner, Eqs. (11) and (12) are substituted into Eq. (8) to give

dM

Mk

Mk

Mp

dp

¿

¾

½

¯

®

21

11

2

(13)

Thus, from the relationships derived from above, the entropy change is

given by substituting Eqs. (11) and (12) into Eq. (9)

dM

Mk

Mk

MR

ds

¿

¾

½

¯

®

21

11

2

(14)

Similarly, the actual change of the Mach number itself will be given by

substituting Eqs. (11) and (13) to Eq. (5) to give

dM

Mk

Mk

k

k

Mk

k

MkD

dx

c

f

¿

¾

½

¯

®

¸

¹

·

¨

©

§

21

111112

4

23

(15)

Table 5.1 Change of properties in the Fanno-line flow

Property Subsonic flow

1

M

Supersonic flow

1!

M

s

M

u

U

T

p

Equations (11) to (15) give the change of properties,

u

,

U

,

T

,

p

,

s

and

M

. It will be convenient to verify the changes of a state by the Mach

number whether the flow is subsonic or supersonic. Table 5.1 shows the

summarized results. As seen in Table 5.1, for subsonic flow ( 1

M

), when

the Mach number increases, the change of the Mach number along the tube

will be

0!dxdM from Eq. (15), implying the fact that the effective cross

section area decreases. This effect concerns the effective increase of the

thickness of the boundary layer, since the flow includes the effect of vis-

cosity.

From Table 5.1, we also see that the frictional effects cause the fluid to

tend toward 1

M

for both initially subsonic and supersonic conditions.

261

5 Compressible Flow

This fact indicates, if a tube length is sufficiently long enough, that the

flow is choked off due to the friction. We may be able to integrate Eqs.

(11)~(15) between a reference point of flow to a point where the flow

reaches the Mach number, as schematically depicted in Fig. 5.16. For ex-

ample, if we integrate Eq. (15), we obtain

dM

Mk

M

Mk

dx

D

c

M

x

x

f

³³

¿

¾

½

¯

®

1

2

2

3

21

122

4

*

(16)

and

2

2

2

2

max

1

21

1

In

2

1

4

kM

M

Mk

Mk

k

k

L

D

c

f

¿

¾

½

¯

®

(17)

where we set

xxL

max

.

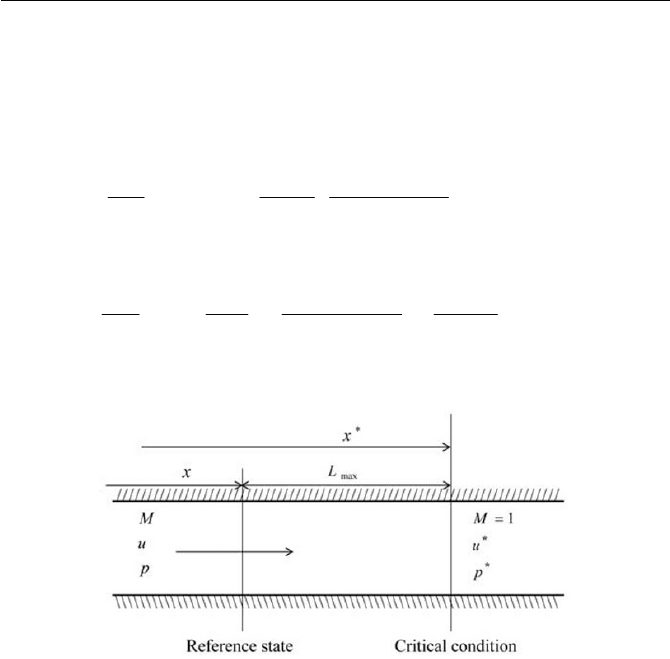

Fig. 5.16 Approach to critical condition

It appears that the flow reaches the choking condition at

*

xx from an ar-

bitrary point

x

in a tube.

max

L is the maximum length, which is called the

limiting length.

Now cases are examined in order to gain the trend in the properties

change along the distance, particularly in the Mach number. From Eq. (17),

Fig. 5.17 is a plot of a Mach number

2

M at a distance

2

x

from a refer-

ence point

x

, where a reference Mach number is denoted by

2

M . For ex-

ample, a flow with a Mach number 7.0

M at a point of

x

reaches

1

2

M at approximately 20

max2

. L where the flow is choked. In the case

where the length of tube is longer than

max2

L , the flow cannot reach 1

M

along the tube, but only at the exit, where the flow is chocked. The mass

flow rate decreases in the case of a tube longer than

max2

L . When a flow is

262